Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the factors that may influence the prolonged urinary leakage following percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL).

Materials and Methods:

A total of 936 consecutive patients underwent PCNL during the study period from April 2013 to December 2014 at our center, and data were recorded prospectively. Patients who required stage PCNL, chronic renal failure and diabetic patients, concurrent ureteric stone and patients in whom double-J stent was placed because of ureteropelvic injury, or pelvicalyceal extravasation were excluded from the study. After exclusion, 576 patients were included in the study. The predictive factors that may lead to prolonged urinary leakage after PCNL were broadly categorized into patient-related factors and procedure-related factors. Patients were divided into two groups: Group 1 (n = 32) – Required double-J stent placement due to prolonged urinary leakage (>48 h) after removal of the nephrostomy tube. Group 2 (n = 544) – Did not require double-J stent placement.

Results:

Patient-related factors such as stone complexity, grade of hydronephrosis, renal parenchymal thickness in access line, and intra-parenchymal renal pelvis were most important factors for prolonged urinary leakage (P < 0.05, P < 0.05, P < 0.05, and P < 0.05, respectively), while procedure-related factors such as multiple punctures, surgeon's experience, and residual stones were most important factors for prolonged urinary leakage (P < 0.05, P < 0.05, and P < 0.05, respectively).

Conclusion:

In the present study, several factors appear to affect post-PCNL prolonged urinary leakage. We suggest that patients who are at increased risk of prolonged urinary leakage double-J stent should be placed at the end of PCNL procedure.

Keywords: Intra-parenchymal renal pelvis, renal parenchymal thickness in access line, residual stones

INTRODUCTION

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) was described by Fernström and Johansson in 1976.[1] It is a well-established technique for treatment of large (>2 cm) or multiple kidney stones, cases with struvite or cystine stones, cases in which stone removal failed with extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, or cases accompanied by anatomical malformation, with over 90% success rate.[1,2] However, PCNL is not without complications with a recent multi-center study showing the overall complication rate of 20.5%.[3,4,5] Bleeding and urine leakage through the percutaneous tract are common event and bothersome to both patients and surgeon. Nephrostomy catheters in varying diameters are used after standard PCNL operations to provide renal drainage and to tamponade bleeding.[6] Nevertheless, urine leakage and bleeding along the nephrostomy tract are still a main concern in PCNL procedure. In this study, we evaluated the parameters affecting prolonged urinary leakage following standard PCNL.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 936 consecutive patients underwent PCNL during the study period from April 2013 to December 2014 at our center, and data were recorded prospectively. All patients requiring single stage PCNL with single or multiple access were included in our study. Those patients who required stage PCNL, chronic renal failure (CRF) and diabetic patients, concurrent ureteric stone, history of storage and voiding lower urinary tract symptoms and patients in whom double-J stent was placed because of ureteropelvic injury or pelvicalyceal extravasation, and tubeless PCNL were excluded from the study. After exclusion, 576 patients were included in our study. Preoperative radiological investigation consisted of computed tomography (CT) urography, X-ray of kidney, ureter, and bladder (KUB) region, and ultrasonography (USG) KUB region. All patients were evaluated preoperatively for renal function, hemostasis, and urinary infection. Patients underwent PCNL as per standard protocol after ensuring sterile urine. Patients were placed in prone position, and in the initial step, stone-guided puncture was done with 22G needle using C-arm fluoroscopy. Access was confirmed by aspirating the urine, and air pyelogram was made. Access to the selected calyx was performed by the attending urologist intra-operatively with the aid of C-arm using 18G needle. The tract was dilated with Alken's serial metallic dilator up to 30 F. Stone clearance was confirmed intra-operatively by fluoroscopy. No double-J stent was placed. A 16 F Nelaton catheter was placed inside the renal pelvis or involved calyx at the end of the procedure in all cases. Antibiotic prophylaxis was given to all the patients. Complete blood counts and renal function test were obtained in all patients postoperatively after 24 h. Fever of ≥38°C was considered as significant. On postoperative day 1, the Foley catheter was removed, plain film of the KUB was obtained. The decision about removing the nephrostomy tube was based on the color of the urine coming from the tube. The nephrostomy tube was removed on postoperative day 2 (mean duration 48 h) after antegrade nephrostography showing ureteral drainage down to the bladder. The percutaneous access site dressing was replaced when the patient informed the duty doctor that the dressing had become wet. Urine leakage persisting 48 h after removal of the nephrostomy tube was considered “prolonged urine leakage” and double-J stent was placed in these patients. Residual stones were assessed postoperatively by X-ray KUB, USG, and/or CT scan in selected cases. The procedure was considered successful if the patient was either stone free or had only a clinically insignificant residual fragment (defined as <4 mm, nonobstructive, noninfectious, and asymptomatic residual fragments). Larger stones were considered residual stones and were evaluated. The mean hemoglobin (Hb) drop was calculated, considering the hemograms that were obtained 24 h before surgery and on day 1 after surgery, along with any blood transfusions; ([preoperative Hb hematocrit (Hct) − postoperative Hb]) − (number of units transfused 1 g/dl Hb [3% for Hct] per unit transfused).[7] The factors that may lead to prolonged urinary leakage after PCNL were broadly categorized into patient-related factors [Table 1] and procedure-related factors [Table 2]. Patient-related factors that were analyzed were patient age, sex, body mass index (BMI), history of ipsilateral renal surgery (open or PCNL), treatment side (right/left), stone burden, the degree of hydronephrosis (measured by Society For Fetal Urology Hydronephrosis Grading System),[8] and intra-parenchymal renal pelvis. Thickness of renal parenchymal tissue in the access line was determined by CT scan. Stone complexity was classified using the validated Guy's stone score (GSS) as GSS I, II, III, and IV. The procedure-related factors which are analyzed were calyx of puncture (upper/middle/lower), puncture site (subcostal/supracostal), number of access (single/multiple), tract length (determined by measuring the distance between the skin and the calyx in access line that underwent PCNL at a 30° angle with 18G initial puncture needle), surgeon's experience (trainee resident), procedure time, and residual stones. Stone size was calculated according to European Association of Urology guidelines. These factors were compared for the presence and duration of urine leakage.

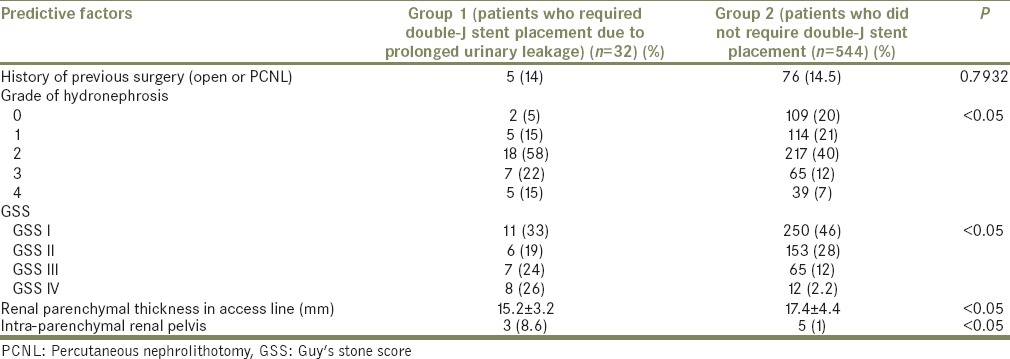

Table 1.

Impact of patient-related factors on prolonged urinary leakage after PCNL

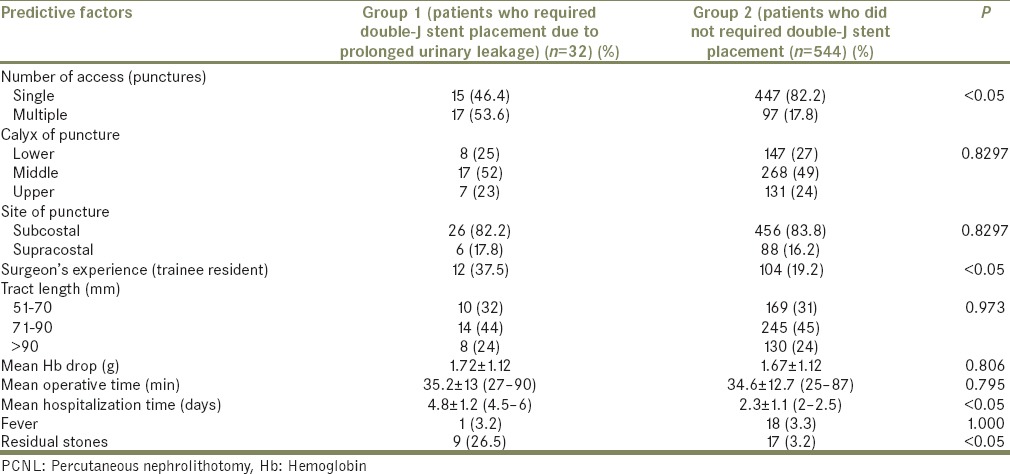

Table 2.

Impact of procedure-related factors on prolonged urinary leakage after PCNL

Parameters studies between two groups as follow:

Group 1 (n = 32): Those patients who required double-J stent placement due to prolonged urinary leakage (urine leakage persisting >48 h) after removal of the nephrostomy tube

Group 2 (n = 544): Those patients who did not require double-J stent placement.

At 1-month follow-up, an overall stone-free rate of 93.6% was achieved after one session of PCNL. In the present study, 32 (5.5%) patients underwent double-J stent placement because of prolong urinary leakage after PCNL.

Statistical analysis

The data were entered in an Excel (Analyse-it for Microsoft) database and analyzed with an SPSS version 19.0 (IBM SPSS statistics 19 SPSS Inc.) statistical software package using the Chi-square test, Student's t-test, and Fischer exact test. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

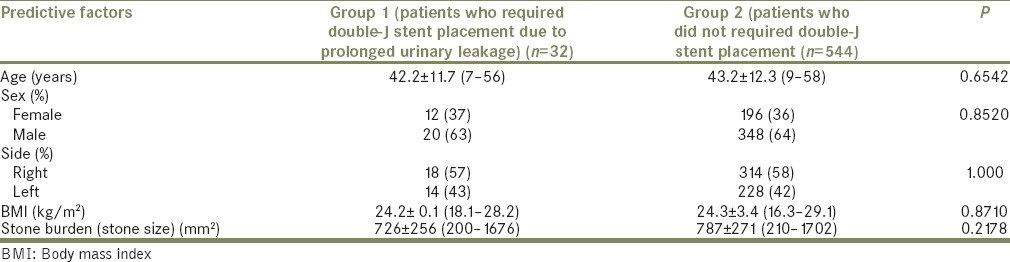

Patient demographics are outlined in Table 3. The impact of patient-related factors on prolonged urinary leakage after PCNL were compared in both groups and are summarized in Table 1. Both groups were comparable in age, sex, laterality (side), and BMI (P = 0.6542, P = 0.8520, P = 0.8884, and P = 0.8710, respectively). History of previous surgery (open or PCNL) was also comparable in both groups (P = 0.7932). Stone burden in Group 1 and Group 2 was 726 ± 256 mm2 and 787 2 ± 71 mm2, respectively, and was also comparable (P = 0.2178). Patient-related factors that were found to be statistically significant and affect the prolong urinary leakage were grade of hydronephrosis, stone complexity (classified using the validated GSS as GSSI, II, III, and IV), and renal parenchymal thickness in the PCNL access line. As the degree of hydronephrosis increases, the incidence of prolong urinary leakage also increases (P < 0.05). A number of patients in GSS III and IV were statistically significant in Group 1 (P < 0.05). Mean renal parenchymal thickness in Group 1 and Group 2 was 15.2 ± 3.2 and 17.4 ± 4.4, respectively, which were found to be statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Demographics of patients

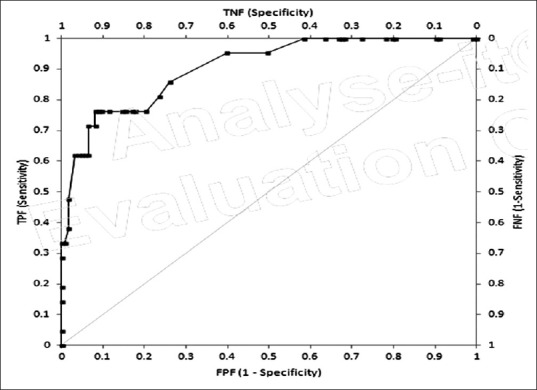

The impact of operative procedure-related factors on prolonged urinary leakage after PCNL were compared in both groups and are summarized in Table 2. The calyceal access (lower, middle, and upper calyx), puncture site (supracostal/subcostal), tract length (distance between skin and the calyx that underwent PCNL at 30° angle), procedure time, and mean Hb drop were comparable in both groups (P = 0.8297, P = 0.6288, P = 1.000, P = 0.7954, and P = 0.8062, respectively). Operative procedure-related factors that were found to be statistically significant were multiple punctures, intra-parenchymal renal pelvis, and trainee residents (P < 0.05, P < 0.05, and P < 0.05, respectively). The mean hospitalization time was more in Group 1 as compared to Group 2 (4.82 ± 1.2 days and 2.3 ± 1.1 days, respectively, P < 0.05). Residual stone fragments were significantly higher in Group 1 compared to Group 2 (P < 0.05). Postoperative fever was not found to be statistically significant (P = 1.000). In the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) [Figure 1], the best cut-off point of renal parenchymal thickness in access line was 17.0 mm. Values <17.0 mm increased the morbidity and duration of hospitalization of patients due to prolonged urinary leakage (sensitivity - 95.2%, specificity - 60.2%, positive predictive value - 26%, negative predictive value - 99%, Youden's index - 55.4%, and area under curve - 0.905; P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis, The best cut-off point for renal parenchymal thickness in access line was 17.0 mm. Values <17.0 mm increased the morbidity and duration of hospitalization of patients due to prolonged urinary leakage (sensitivity - 95.2%, specificity - 60.2%, positive predictive value - 26%, negative predictive value - 99%, Youden's index - 55.4% area under curve - 0.905, P < 0.05)

DISCUSSION

PCNL is the treatment modality of choice for most renal stones larger than 2 cm and for complex renal stones.[9]

In spite of high success rates, PCNL involves many complications such as blood loss, urinary leakage, urinary tract infection (UTI), urinoma, and serious complications such as adjacent organ injury and urosepsis.[10] Modified Clavien grading system has been shown to be a reliable classification system for comparison of post-PCNL complication.

Tefekli et al.[10] used the modified Clavien grading system, urinary leakage from the nephrostomy site for <12 h was considered as Grade II complication while the double-J stent placement for urine leakage more than 24 h was considered as Grade III complication. This study also showed that prolonged urinary leakage that increases the duration of hospital stay is the most common type of Grade IIIA complication.

Dirim et al.[11] reported urinary leakage in 70.2% of patients. The median duration of leakage in their study was 14 h (1–200 h). Binbay et al.[12] reported that between 4.3% and 5% patients required double-J stent placement because of prolonged urinary leakage after PCNL.

In present study, 32 (5.5%) patients underwent double-J stent placement because of prolonged urinary leakage after PCNL. Binbay et al.[12] reported that stone burden prolongs the duration of hospital stay due to prolonged urinary leakage while Uyeturk et al.[13] demonstrated opposite results. We do not think that stone burden influences the post-PCNL prolonged urinary leakage.

Margel et al.[14] demonstrated that PCNL can be performed successfully without increased risk of complications in patients with a history of open surgery. In present study, history of open surgery does not influence the prolong urinary leakage.

Dirim et al.[11] and Binbay et al.[12] evaluated the correlation between the degree of renal hydronephrosis and prolonged urinary leakage. Studies concluded that duration increases with the degree of hydronephrosis. In the present study, we found the same result.

Uyeturk et al.[13] reported that renal parenchymal thickness in access line is more significantly correlated with duration of urinary leakage than grade of hydronephrosis. The present study also confirmed that renal parenchymal thickness in access line inversely correlated with prolong urinary leakage. Thomas et al.[15] demonstrated that post-PCNL complication is more in GSS III and IV. Most of these patients were managed by multiple punctures and also needed relook procedure for residual stone.[16] There is no study that correlated the prolong urinary leakage with GSS. In our study, prolonged urinary leakage is statistically significant in GSS III and IV. de la Rosette et al.,[17] Allen et al.,[18] and Tanriverdi et al.[19] demonstrated that complications are higher during the learning phase of PCNL. In present study, PCNL performed by trainee residents were significantly associated with prolong urinary leakage. We find that selection of appropriate calyx, short tract during tract dilatation are the major intra-operative factors, which require multiple punctures and repeated tract dilatation, might explain the prolong duration of urinary leakage.

The present study is the first to correlate the intra-parenchymal renal pelvis and prolonged urinary leakage after PCNL. In our study, it is significantly associated with prolonged urinary leakage. Elevated pressures within a small intra-parenchymal renal pelvis might explain the increased risk of prolonged urinary leakage.[20]

Perks et al.[21] reported that skin to stone distance on CT is one of the strong factors in producing the success of shock wave lithotripsy. Gonulalan et al.[22] reported that skin to stone distance has no impact on outcomes of PCNL. The present study is the first to correlate the skin to stone distance and prolonged urinary leakage after PCNL. In present study, we measured the tract length along access line (distance between the skin and the calyx in access line that underwent PCNL at 30° angle), which is not found to be significantly correlated with prolonged urinary leakage.

In the present study, no relationship is found between postoperative drop in Hb level and prolonged urinary leakage.

Fever secondary to UTI is one of the most common complications of PCNL.[23] In our study, fever is not found to be influencing the prolonged urinary leakage.

Binbay et al. demonstrated that post-PCNL residual stone fragments increases the duration of urinary leakage.[12] We also find that residual stone fragments increase the prolonged urinary leakage.

This is a prospective study, and it is the strength of present study as most of the previous studies are retrospective in nature documenting the urinary leakage after PCNL, correlating the patient-related factors and procedure-related factors.

This study carries the limitations that we did not compare the nephrostomy tube size[24,25] with prolonged urinary leakage, we also excluded the diabetic and CRF patients that may be the one of the factors for prolonged urinary leakage.

Present study suggested that prolonged urinary leakage is significantly associated with stone complexity (which is best measured by validated GSS), degree of hydronephrosis, renal parenchymal thickness in access line, intra-parenchymal renal pelvis, multiple access, and presence of residual stone. Prolonged urinary leakage was also found to be statistically significant among trainee residents. Distance from skin to desired calyx puncture (tract length) has no effect on prolonged urinary leakage.

CONCLUSION

In the present study, several factors appear to affect post-PCNL prolonged urinary leakage. Although most of the urinary leakage was managed conservatively, it increases the morbidity and duration of hospitalization of patients. We suggest that patients who are at increased risk of prolonged urinary leakage (Grade III, Grade IV hydronephrosis, GSS III, GSS IV, reduced parenchymal thickness, require multiple access tract, intra-parenchymal renal pelvis, and residual stones), double-J stent should be placed at the end of PCNL procedure.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fernström I, Johansson B. Percutaneous pyelolithotomy. A new extraction technique. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1976;10:257–9. doi: 10.1080/21681805.1976.11882084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellman GC, Davidoff R, Candela J, Gerspach J, Kurtz S, Stout L. Tubeless percutaneous renal surgery. J Urol. 1997;157:1578–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monga M, Oglevie S. Minipercutaneous nephorlithotomy. J Endourol. 2000;14:419–21. doi: 10.1089/end.2000.14.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Kohlany KM, Shokeir AA, Mosbah A, Mohsen T, Shoma AM, Eraky I, et al. Treatment of complete staghorn stones: A prospective randomized comparison of open surgery versus percutaneous nephrolithotomy. J Urol. 2005;173:469–73. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000150519.49495.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Preminger GM, Assimos DG, Lingeman JE, Nakada SY, Pearle MS, Wolf JS., Jr AUA Nephrolithiasis Guideline Panel. Chapter 1: AUA guideline on management of staghorn calculi: Diagnosis and treatment recommendations. J Urol. 2005;173:1991–2000. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000161171.67806.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Labate G, Modi P, Timoney A, Cormio L, Zhang X, Louie M, et al. The percutaneous nephrolithotomy global study: Classification of complications. J Endourol. 2011;25:1275–80. doi: 10.1089/end.2011.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stoller ML, Wolf JS Jr, St Lezin MA. Estimated blood loss and transfusion rates associated with percutaneous nephrolithotomy. J Urol. 1994;152(6 Pt 1):1977–81. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)32283-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernbach SK, Maizels M, Conway JJ. Ultrasound grading of hydronephrosis: Introduction to the system used by the Society for Fetal Urology. Pediatr Radiol. 1993;23:478–80. doi: 10.1007/BF02012459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tiselius HG, Ackermann D, Alken P, Buck C, Conort P, Gallucci M, et al. Working Party on Lithiasis. Guidelines on urolithiasis. Eur Urol. 2001;40:362–71. doi: 10.1159/000049803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tefekli A, Ali Karadag M, Tepeler K, Sari E, Berberoglu Y, Baykal M, et al. Classification of percutaneous nephrolithotomy complications using the modified clavien grading system: Looking for a standard. Eur Urol. 2008;53:184–90. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dirim A, Turunc T, Kuzgunbay B, Hasirci E, Tekin MI, Ozkardes H. Which factors may effect urinary leakage following percutaneous nephrolithotomy? World J Urol. 2011;29:761–6. doi: 10.1007/s00345-010-0596-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Binbay M, Sari E, Tepeler A, Erbin A, Savas O, Muslumanoglu AY, et al. Characteristics of patients requiring double-J placement because of urine leakage after percutaneous nephrolithotomy. J Endourol. 2009;23:1945–9. doi: 10.1089/end.2009.0154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uyeturk U, Gucuk A, Kemahli E, Dagistan E, Yildiz M, Yilmaz B, et al. Factors influencing the duration of urine leakage following percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Adv Urol 2014. 2014:105709. doi: 10.1155/2014/105709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Margel D, Lifshitz DA, Kugel V, Dorfmann D, Lask D, Livne PM. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy in patients who previously underwent open nephrolithotomy. J Endourol. 2005;19:1161–4. doi: 10.1089/end.2005.19.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas K, Smith NC, Hegarty N, Glass JM. The Guy's stone score – Grading the complexity of percutaneous nephrolithotomy procedures. Urology. 2011;78:277–81. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muslumanoglu AY, Tefekli A, Karadag MA, Tok A, Sari E, Berberoglu Y. Impact of percutaneous access point number and location on complication and success rates in percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Urol Int. 2006;77:340–6. doi: 10.1159/000096339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de la Rosette JJ, Laguna MP, Rassweiler JJ, Conort P. Training in percutaneous nephrolithotomy – A critical review. Eur Urol. 2008;54:994–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allen D, O’Brien T, Tiptaft R, Glass J. Defining the learning curve for percutaneous nephrolithotomy. J Endourol. 2005;19:279–82. doi: 10.1089/end.2005.19.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanriverdi O, Boylu U, Kendirci M, Kadihasanoglu M, Horasanli K, Miroglu C. The learning curve in the training of percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Eur Urol. 2007;52:206–11. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomaszewski JJ, Cung B, Smaldone MC, Mehrazin R, Kutikov A, Viterbo R, et al. Renal pelvic anatomy is associated with incidence, grade, and need for intervention for urine leak following partial nephrectomy. Eur Urol. 2014;66:949–55. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perks AE, Schuler TD, Lee J, Ghiculete D, Chung DG, D’A Honey RJ, et al. Stone attenuation and skin-to-stone distance on computed tomography predicts for stone fragmentation by shock wave lithotripsy. Urology. 2008;72:765–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonulalan U, Akand M, Coban G, Cicek T, Kosan M, Goktas S, et al. Skin-to-stone distance has no impact on outcomes of percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Urol Int. 2014;92:444–8. doi: 10.1159/000356562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Draga RO, Kok ET, Sorel MR, Bosch RJ, Lock TM. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy: Factors associated with fever after the first postoperative day and systemic inflammatory response syndrome. J Endourol. 2009;23:921–7. doi: 10.1089/end.2009.0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Desai MR, Kukreja RA, Desai MM, Mhaskar SS, Wani KA, Patel SH, et al. A prospective randomized comparison of type of nephrostomy drainage following percutaneous nephrostolithotomy: Large bore versus small bore versus tubeless. J Urol. 2004;172:565–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000130752.97414.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li LY, Gao X, Yang M, Li JF, Zhang HB, XU WF, et al. Does a smaller tract in percutaneous nephrolithotomy contribute to less invasiveness?. A prospective comparative study. Urology. 2001;58:345–50. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]