Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the utility of recommended laboratory testing to identify secondary causes in older men with osteoporosis, we examined prevalence of laboratory abnormalities in older men with and without osteoporosis.

Methods

1572 men aged ≥65 years in the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men study completed bone mineral density (BMD) testing and a battery of laboratory measures, including serum calcium, phosphorus, alkaline phosphatase, parathyroid hormone (PTH), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), 25-OH vitamin D, total testosterone, spot urine calcium/creatinine ratio, spot urine albumin-creatinine ratio, creatinine-derived estimate glomerular filtration rate, 24-hour urine calcium, and 24-hour urine free cortisol. Using cross-sectional analyses, we calculated prevalence ratios (PR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the association of any and specific laboratory abnormalities with osteoporosis, and the number of men with osteoporosis needed to test to identify one additional laboratory abnormality compared to testing men without osteoporosis.

Results

Approximately 60% of men had ≥1 laboratory abnormality in both men with and without osteoporosis. Among individual tests, only vitamin D insufficiency (PR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.05–1.22) and high alkaline phosphatase (PR, 3.05; 95% CI, 1.52–6.11) were more likely in men with osteoporosis. Hypercortisolism and hyperthyroidism were uncommon and not significantly more frequent in men with osteoporosis. No osteoporotic men had hypercalciuria.

Conclusions

Though most of these older men had ≥1 laboratory abnormality, few routinely recommended individual tests were more common in men with osteoporosis than in those without osteoporosis. Possibly excepting vitamin D and alkaline phosphatase, benefit of routine laboratory testing to identify possible secondary causes in older osteoporotic men appears low. Results may not be generalizable to younger men or to older men in whom history and exam findings raise clinical suspicion for a secondary cause of osteoporosis.

Keywords: Osteoporosis, male, aged, bone mineral density

Introduction

The prevalence of secondary factors associated with osteoporosis in older men with osteoporosis is reported to be high.[1] However, it is unclear whether these factors cause osteoporosis, or whether their detection will lead to improved bone outcomes. Both the 2012 Endocrine Society and 2014 National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) guidelines recommend that older men being evaluated for osteoporosis undergo a battery of laboratory tests, including serum calcium, phosphate, creatinine, alkaline phosphatase, liver function, 25(OH) vitamin D, total testosterone, complete blood count, and 24-hour urinary calcium.[2, 3] The NOF guidelines further recommend measurement of serum magnesium, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), parathyroid hormone (PTH), and bone turnover markers. Both guidelines recommend consideration of additional testing depending on history or physical exam findings. In theory, identification and treatment of underlying causes of osteoporosis could improve bone density and reduce fracture risk. Conversely, if identified laboratory abnormalities are no more common in older men with versus without osteoporosis, or their prevention or treatment would not reduce fracture risk, routine measurement of these laboratory tests may not be warranted.

The aim of the present study is to contribute towards better understanding of the benefits and harms of routine laboratory testing in older men with osteoporosis by comparing the prevalence of selected abnormal laboratory findings in older men with and without osteoporosis.

Methods

Participants

Community-dwelling men aged ≥65 years were recruited to participate in the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study (MrOS), a prospective cohort study at six U.S. sites: Birmingham, AL; Minneapolis, MN; Palo Alto, CA; Monongahela Valley near Pittsburgh, PA; Portland, OR; and San Diego, CA. MrOS exclusion criteria included inability to walk without assistance from another person and a history of bilateral hip replacement. The institutional review boards at all participating centers approved the study protocol and written informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study. Details of the MrOS study design and recruitment have been described elsewhere.[4, 5]

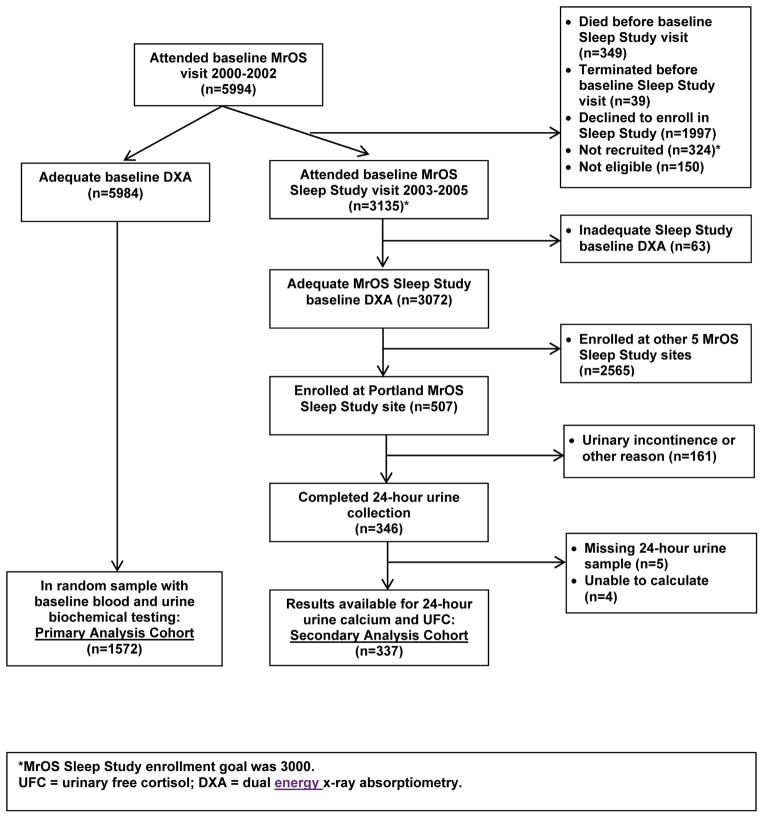

Of 5994 MrOS participants who attended the baseline examination (March 2000 to April 2002), 5984 (99.8%) completed technically adequate measurements of hip and spine BMD by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA). Of these men, baseline biochemical testing was performed in a random sample of 1572, forming our primary analysis cohort (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Analysis cohorts.

From December 2003 to March 2005, MrOS participants were invited to participate in the MrOS Sleep Study. Of 3135 men who enrolled in the MrOS Sleep Study, 3072 (97.9%) completed adequate measurements of hip BMD by DXA, including 507 from the Portland study site. Of these 507 men, 24 hour urine collection was performed in 346 without urinary incontinence or other exclusion, in whom data were available for 24-hour calcium and 24-hour free cortisol in 337, forming our secondary analysis cohort (Figure 1).

Measurement of Bone Density

At baseline and sleep visits, areal BMD (g/cm2) was measured at the right hip and lumbar spine using DXA (QDR4500W, Hologic, Inc., Waltham, MA) unless the subject reported a right hip replacement or metal objects in the right leg, in which case the left hip was measured. MrOS DXA quality assurance measures have been detailed previously.[5] Based on common phantoms measured at all clinics, variability across clinics was within acceptable limits, and cross-calibration correction factors were not required. Precision of spine and hip DXA scans was 1 to 2%.

Biochemical Measures

Fasting morning blood and first morning urine voids were collected at the baseline visit, and 24-hour urine was collected at the sleep visit. Blood was processed for serum and stored at −70°C while urine was stored at −20°C. Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) was measured using a third-generation assay (ADVIA Centaur; Siemens Diagnostics), with an interassay coefficient of variation (CV) at 2.08 mIU/L of 2.4%. Total intact PTH was measured using an immunoradiometric assay from Scantibodies (3KG600), with an interassay CV of 8.4%. 25-OH vitamin D was measured using liquid chromatography mass spectroscopy (Mayo Clinic Labs) and duplicate pooled serum controls, with an interassay CV of 4.4%. Total testosterone was analyzed by gas chromatograph/mass spectrometry assay (Taylor Technology). Duplicate aliquots were assayed and averaged, and interassay CV was 6.0%. Serum creatinine, calcium, phosphorus, and alkaline phosphatase were measured using a Roche COBAS Integra 800 and spot urine creatinine, and spot and 24-hour urine calcium were measured using a Roche COBAS Integra 6000 automated analyzer (Roche Diagnostics Corp), and both serum and urine assays used an enzymatic method calibrated with materials assayed by isotope-dilution mass spectometry. Respectively, interassay CVs were 5.3%, 2.6%, 2.7%, 2.4%, 2.5%, 1.6%, and 1.6%. Spot urine albumin was measured using nephelometry (Behring-Dade), with an interassay CV of 3.5%. 24-hour urine free cortisol (UFC) was measured using high performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (Esoterix Laboratory), with an intraassay CV of 5.7%.

Covariate Measurements

All covariate measures were collected at MrOS baseline. These included date of birth, race, current smoking and/or alcohol use, parental history of hip fracture, and self-reported physician diagnosis of fractures since age 50, kidney stones, rheumatoid arthritis, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, diabetes, Parkinson’s disease, stroke, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A medication inventory was used to classify medications used within the preceding 30 days into categories by their ingredients, including oral corticosteroid use.[6] In-clinic measures included height (stadiometer) and weight (balance beam or digital scale), from which we calculated body mass index (BMI) as kg/m2.

Statistical Analyses

We defined osteoporosis at each BMD measurement as a T-score ≤ −2.5 at either total hip, femoral neck, or lumbar spine using a male reference database for hip sites,[7] and unpublished Hologic norms for lumbar spine. We defined hyperparathyroidism as total intact PTH >66 pg/mL, and hyperthyroidism as TSH <0.55 mIU/L. We defined vitamin D deficiency as 25(OH) vitamin D <20 ng/ml. We defined kidney disease as either eGFRcr <60 ml/min/1.73m2 using the CKD-EPI 2009 equation[8] or urinary albumin/creatinine ratio (ACR) ≥30 mg/g. Because the limit of sensitivity of our assay for urinary albumin is 3 mg/L, samples that registered below this level were considered to be 3 mg/L (n=841). We defined low testosterone as total testosterone <200 ng/dl. We defined hypercalcemia as serum calcium >10.4 mg/dL, hyperphosphatemia as serum phosphorus >4.7 mg/dL, and high alkaline phosphatase as a serum level >129 IU/L. We defined hypercalciuria as a spot urine calcium/creatinine ratio of ≥0.3. We then determined the proportion of men in the primary analysis cohort with at least one of these laboratory abnormalities. Secondarily, in participants who completed 24-hour urine collection, we defined hypercalciuria as >300 mg/24 hours, and probable hypercortisolism as a calculated urine free cortisol (UFC) >100 mcg/24 hours.

Comparisons of baseline characteristics between men with and without osteoporosis using a male reference database were analyzed using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. We examined the cross-sectional association between osteoporosis status and the prevalence of specific biochemical abnormalities using unadjusted log binomial regression analyses, calculating prevalence ratio (PR) (prevalence of an abnormal result among men with osteoporosis divided by the prevalence among men without osteoporosis) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Then, from the inverse of the absolute risk difference (ARD) and its 95% CI, we calculated the number of older men who would need laboratory testing to identify one more abnormality in those with osteoporosis compared to a same sized group of nonosteoporotic older men (number needed to test [benefit], or NNTB). When prevalence of a laboratory abnormality was higher in the nonosteoporotic men, NNTB was expressed as a negative number whose absolute value reflected the number of older men needing testing to identify one more abnormality in those without osteoporosis compared to a same sized group of osteoporotic older men, a value that also could be considered the number needed to test [harm], or NNTH). When 95% CI for the ARD included zero, the NNTB 95% CI ranged from values of NNTB to NNTH, including infinity (for ARD = 0) in the middle of the range.[9] In sensitivity analyses, we used alternative definitions of laboratory abnormalities, including vitamin D insufficiency at 25(OH) vitamin D <30 ng/ml, low total testosterone at <300 ng/dl, hypercalciuria with a spot urine calcium/creatinine ratio of ≥0.2, and possible hypercortisolism as a UFC >50 mcg/24 hours.

Last, we performed stratified analyses to explore whether the prevalence of laboratory abnormalities (PR and 95% CI) was greater in selected subsets of men with osteoporosis postulated to be more likely to have a secondary cause for their osteoporosis: younger men (age <75 vs. ≥75 years), heavier men (BMI ≥30 vs. <30), men with past fractures, and in men defined as osteoporotic based on a T-score ≤ −2.5 at either total hip, femoral neck, or lumbar spine using a female reference database.

Results

Within the 1572 men with both BMD and laboratory measures available at baseline, 10.4% (n=163) met criteria for osteoporosis defined as a T-score ≤ −2.5 at total hip, femoral neck, or lumbar spine using a male reference base, whereas only 5.6% (n=88) met criteria for osteoporosis using a female reference database. Compared to men without osteoporosis, those with osteoporosis were significantly older, less likely to be obese, and more often had a history of fracture or kidney stones (Table 1). Among the 337 men with both BMD and 24-hour urine measures available at the sleep visit, 7.0% (n=24) met criteria for osteoporosis using a male reference base, and 5.6% (n=19) met criteria using a female reference database.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics by baseline osteoporosis status*

| Variable, mean (SD) or % (n) | Osteoporosis* (n=163) | No Osteoporosis (n=1409) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 75.2 (6.1) | 73.6 (5.9) | 0.001 |

| White race | 88.3 (144) | 91.7 (1292) | 0.15 |

| BMI ≥30 | 10.4 (17) | 21.3 (300) | 0.001 |

| Current alcohol use ≥3 drinks/day | 11.0 (18) | 12.4 (175) | 0.61 |

| Current smoker | 6.8 (11) | 3.3 (46) | 0.02 |

| Current oral corticosteroid use | 4.5 (7) | 2.4 (32) | 0.11 |

| Parental hip fracture | 22.8 (18) | 24.1 (183) | 0.79 |

| Fracture after age 50 | 32.7 (53) | 21.4 (301) | 0.001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis† | 3.7 (6) | 5.0 (71) | 0.45 |

| Hyperthyroidism† | 2.5 (4) | 1.6 (22) | 0.40 |

| Hypothyroidism† | 9.2 (15) | 7.5 (105) | 0.43 |

| Kidney stones† | 19.0 (31) | 12.7 (179) | 0.02 |

| Diabetes† | 10.4 (17) | 11.4 (160) | 0.72 |

| Parkinson’s disease† | 1.2 (2) | 0.9 (12) | 0.65 |

| Stroke† | 8.0 (13) | 5.8 (81) | 0.26 |

| COPD† | 14.1 (23) | 11.5 (162) | 0.33 |

SD = standard deviation; BMI = body mass index (kg/m2); COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Osteoporosis defined as T-score ≤ −2.5 at total hip, femoral neck, or lumbar spine using a male reference database.

Based on participant self-report of physician diagnosis.

Association between osteoporosis and selected laboratory-defined clinical diagnoses

Of the 163 men with osteoporosis in the primary analysis cohort, 58.3% had at least one of several laboratory abnormalities postulated as potential secondary factors contributing to osteoporosis, including 30.7% with 25(OH) vitamin D deficiency (<20 ng/ml), 17.1% with kidney disease defined as either eGFRcr <60 ml/min/1.73m2 or ACR >30 mg/g, and 10.5% with (hyperthyroidism) TSH <0.55 mIU/L (Table 2). However, in unadjusted analyses, men with osteoporosis were not significantly more likely than men without osteoporosis to have any of these laboratory abnormalities collectively (PR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.89–1.20; NNTB, 55.6 [NNTB 9.6 to ∞ to NNTH 14.7]) or individually, except for high alkaline phosphatase or 25(OH) vitamin D insufficiency (<30 ng/ml) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Relative prevalence of selected laboratory abnormalities* in men with and without osteoporosis, PR (95% CI)

| Diagnosis | Osteoporosis, % (n) | No Osteoporosis, % (n) | PR (95% CI) | NNTB (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Definitions of Laboratory Abnormalities | ||||

| Cohort with random baseline serum and spot urine (n=1572) | ||||

| 25(OH) Vitamin D deficiency, <20 ng/mL | 30.7 (50) | 24.7 (348) | 1.24 (0.97–1.59) | 16.7 (NNTB 7.5 to ∞ to NNTH 68.0) |

| Kidney disease, eGFRcr <60 ml/min/1.73m2 or urine ACR>30 mg/g | 17.1 (25) | 17.9 (239) | 0.96 (0.66–1.39) | −125.0 (NNTB 17.6 to ∞ to NNTH 13.8) |

| Hyperthyroidism, TSH <0.55 mIU/L | 2.5 (4) | 2.8 (39) | 0.89 (0.32–2.46) | −333.3 (NNTB 44.7 to ∞ to NNTH 35.2) |

| Low testosterone, <200 ng/dl | 7.6 (12) | 6.2 (87) | 1.22 (0.68–2.18) | 71.4 (NNTB 17.6 to ∞ to NNTH 33.8) |

| Hyperparathyroidism, PTH >66 pg/mL | 6.2 (10) | 3.4 (48) | 1.81 (0.93–3.50) | 35.7 (NNTB 15.2 to ∞ to NNTH 93.7) |

| Hypercalcemia, Ca >10.4 mg/dL | 1.4 (2) | 0.6 (8) | 2.29 (0.49–10.7) | 125.0 (NNTB 37.0 to ∞ to NNTH 86.2) |

| Hyperphosphatemia, PO4 >4.7 mg/dL | 0 (0) | 0.1 (1) | NC | NC |

| High alkaline phosphatase, >129 IU/L | 6.9 (10) | 2.3 (30) | 3.05 (1.52–6.11) | 21.7 (11.4 to 233.4) |

| Hypercalciuria, spot urine calcium/creatinine ratio ≥0.3 | 1.2 (2) | 0.8 (11) | 1.57 (0.35–7.01) | 250.0 (NNTB 45.3 to ∞ to NNTH 76.0) |

| At least 1 of above laboratory abnormalities† | 58.3 (81) | 56.5 (740) | 1.03 (0.89–1.20) | 55.6 (NNTB 9.6 to ∞ to NNTH 14.7) |

| Cohort with 24-hour urine (n=337) | ||||

| Hypercortisolism, UFC >100 mg/24 hr | 2.9 (1) | 1.3 (4) | 2.16 (0.25–18.8) | 66.7 (NNTB 13.9 to ∞ to NNTH 24.2) |

| Hypercalciuria, >300 mg calcium/24 hr | 0 (0) | 0.3 (1) | NC | NC |

| Alternative Definitions of Laboratory Abnormalities | ||||

| Cohort with random baseline serum and spot urine (n=1572) | ||||

| 25(OH) Vitamin D deficiency, <30 ng/mL | 84.1 (137) | 74.1 (1043) | 1.13 (1.05–1.22) | 10.0 (6.2–25.6) |

| Low testosterone, <300 ng/dl | 25.3 (40) | 26.3 (367) | 0.96 (0.73–1.28) | −100.0 (NNTB 16.2 to ∞ to NNTH 12.3) |

| Hypercalciuria, spot urine calcium/creatinine ratio ≥0.2 | 5.6 (9) | 3.6 (50) | 1.55 (0.78–3.10) | 50.0 (NNTB 17.7 to ∞ to NNTH 59.4) |

| Cohort with 24-hour urine (n=337) | ||||

| Hypercortisolism, UFC >50 mg/24 hr | 5.7 (2) | 7.3 (22) | 0.78 (0.19–3.20) | −62.5 (NNTB 15.0 to ∞ to NNTH 10.2) |

PR = prevalence ratio; NNTB = number needed to test (benefit); NNTH = number needed to treat (harm); PTH = parathyroid hormone; TSH = thyroid stimulating hormone; eGFRcr = estimated creatinine-derived glomerular filtration rate; ACR = urinary albumin/creatinine ratio; UFC = urine free cortisol; NC = not calculable.

There were 122 participants with missing laboratory data for at least 1 measure, including the following number with missing data for specific laboratory tests: eGFRcr 91, serum calcium 91, serum phosphorus 91, serum alkaline phosphatase 91, testosterone 18, spot urine calcium 13, PTH 4, TSH 2, 25-OH vitamin D 1, 24-hour UFC 9, 24-hour urine calcium 21.

Defined by presence of any of the following: 25(OH) Vitamin D <20 ng/ml, kidney disease (eGFRcr <60 or ACR ≥30), TSH<0.55 mIU/L, total testosterone <200 ng/dl, PTH >66 pg/mL, serum calcium >10.4 mg/dL, serum phosphorus >4.7 mg/dL, serum alkaline phosphatase >129 IU/L, or spot urine calcium/creatinine ratio ≥0.3.

In additional analyses, though neither men aged <75 or ≥75 years had a statistically significant association between osteoporosis and the likelihood of any laboratory abnormality, there was a borderline significant interaction of this association with age (p=0.06) suggesting a possibly lower likelihood of any laboratory abnormality with osteoporosis in younger versus older men (Table 3). Otherwise, risk of any laboratory abnormality appeared similar in magnitude to overall results in groups of men stratified by BMI or fracture history (Table 3), and in those defined as osteoporotic using a female reference database (PR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.90–1.26).

Table 3.

Relative prevalence of any laboratory abnormality* in men with and without osteoporosis, overall and as a function of participant characteristics, PR (95% CI)

| Prevalence of any laboratory abnormality, % (n) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Osteoporotic Men | Nonosteoporotic Men | PR (95% CI) | P for interaction |

| Overall | 58.3 (81) | 56.5 (740) | 1.03 (0.89–1.20) | NA |

| Age | 0.06 | |||

| <75 yr | 43.5 (27) | 52.8 (410) | 0.82 (0.62–1.10) | |

| ≥75 yr | 70.1 (54) | 61.8 (330) | 1.13 (0.97–1.33) | |

| Fracture history | 0.52 | |||

| Yes | 56.0 (31) | 60.2 (171) | 1.09 (0.87–1.37) | |

| No | 55.0 (50) | 55.4 (567) | 0.99 (0.82–1.20) | |

| BMI | 0.49 | |||

| ≥30 | 66.7 (10) | 70.6 (199) | 0.94 (0.65–1.36) | |

| <30 | 57.3 (71) | 52.6 (541) | 1.09 (0.93–1.28) | |

PR = prevalence ratio; BMI = body mass index; NA = not applicable.

Defined by presence of any of the following: 25(OH) Vitamin D <20 ng/ml, kidney disease (eGFRcr <60 or ACR ≥30), TSH <0.55 mIU/L, total testosterone <200 ng/dl, PTH >66 pg/mL, serum calcium >10.4 mg/dL, serum phosphorus >4.7 mg/dL, serum alkaline phosphatase >129 IU/L, or spot urine calcium/creatinine ratio ≥0.3.

In the smaller sample of men with available 24-hour urine measures, hypercortisolism defined as UFC >100 mcg/24 hours was not significantly more frequent in men with osteoporosis (2.9 vs. 1.3%; PR, 2.16; 95% CI, 0.25–18.8). The only man with urine calcium >300 mg/24 hours did not have osteoporosis.

In sensitivity analyses using alternative definitions of laboratory abnormalities, compared to men without osteoporosis, those with osteoporosis were significantly more likely to have vitamin D insufficiency defined as 25-OH vitamin D <30 ng/ml (84.1% vs. 74.1%; PR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.05–1.22), but not low total testosterone defined as <300 ng/dl, hypercalciuria defined as a spot urine calcium/creatinine ratio ≥0.2, or possible hypercortisolism defined as UFC >50 mcg/24 hours (Table 1).

Discussion

In this cohort of community-dwelling older men, while an abnormality of at least one of several laboratory tests recommended for measurement in men with osteoporosis[2, 3] was common, the prevalence of many individual laboratory test abnormalities appeared rare (e.g. hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria, hyperphosphatemia, hypercortisolism). Further, among individual laboratory tests, only vitamin D insufficiency and high alkaline phosphatase were significantly more prevalent in older men with osteoporosis than in those without osteoporosis.

Our observation that many men with osteoporosis have an abnormality of one or more recommended laboratory tests is consistent with earlier reports.[1, 10] However, these prior case series may have overestimated the degree to which osteoporosis can be attributed to these laboratory abnormalities by not comparing results to those in a nonosteoporotic control group. Other studies have reported a high prevalence of laboratory abnormalities in osteoporotic women.[11–13] However, the only one of these studies that compared the likelihood of laboratory abnormalities to that in a nonosteoporotic comparison group, reported that only the prevalence of low TSH was significantly more common in the women with osteoporosis.[13]

For laboratory testing in older osteoporotic men to be of benefit, identification of specific laboratory abnormalities should inform a clinical decision that leads to improved patient-important health outcomes (e.g. reduced fractures) versus usual care or versus no testing and no change in treatment, all while limiting harms and costs. Issues that may impact the balance of benefits and harms of such testing include: (1) the prevalence of laboratory-defined medical conditions that may contribute to osteoporosis in older men; (2) the validity, reliability and cost of tests for these medical conditions; (3) whether there are treatments for these laboratory-defined conditions that improve important health outcomes; (4) treatment costs; (5) harms of testing; and (5) whether the benefits and/or harms of osteoporosis-specific treatments differ between older osteoporotic men with versus without specific laboratory-defined medical conditions (e.g. risk of bisphosphonate treatment in men with impaired renal function). Even without data addressing all of these issues, our finding that selected laboratory abnormalities were rare and that most others were not significantly more likely in older osteoporotic versus nonosteoporotic men suggests that at least for most of the laboratory measures evaluated in the present study, the benefit of routine testing all older men with osteoporosis for the purpose of identifying potential underlying causes of their osteoporosis may be low. Interpretation of our finding that older men with osteoporosis have a significantly higher risk for vitamin D insufficiency than nonosteoporotic men appears more complicated. While the Women’s Health Initiative reported that calcium plus vitamin D supplementation reduced hip fracture risk among the subgroup of mostly nonosteoporotic postmenopausal women with normal vitamin D levels who were adherent with their supplements, the fracture benefit of this treatment is unknown in older men with osteoporosis and low vitamin D levels.[14]

The major strength of this study is that because MrOS participants were recruited from population-based sources not selected based on a history of osteoporosis or fractures, men with laboratory measures were randomly selected from the larger cohort, and prevalence of laboratory abnormalities in men with osteoporosis was compared to that in a nonosteoporotic control group, results should have been less prone to selection bias than those from earlier case series. Results may be most generalizable to older men identified with osteoporosis by screening or being managed in primary care settings in whom there is no other reason to suspect specific laboratory abnormalities.

Conversely, because MrOS participants are community-dwelling, largely healthy older men, whose osteoporosis was identified by bone density testing performed irrespective of fracture history or other osteoporosis risk factors, findings may have limited generalizability to other populations, including women, younger men, older men whose osteoporosis is identified following clinical fractures, and older men with findings on history or physical examination that raise suspicion for an underlying cause for their osteoporosis. Second, though laboratory testing to identify treatment safety conditions may lead to incidental diagnosis of possible underlying conditions, the potential benefits and harms of such testing was outside the scope of our study question. Third, because of the wide confidence intervals around the estimates of association between osteoporosis and individual laboratory abnormalities, our findings of statistical insignificance could not rule out weak to moderate associations. Because of smaller sample sizes, imprecision may have been a bigger issue in analyses using a female reference database to define osteoporosis, and in analyses stratified by age, BMI, and fracture history. However, estimates of the association of osteoporosis with any laboratory abnormality in these groups appeared similar to those in men overall. Fourth, though spot urine calcium is a surrogate measure for hypercalciuria that may underestimate or overestimate urinary calcium excretion, hypercalciuria also was rare among men with 24-hour urine measures, suggesting that any misclassification was unlikely to have modified our conclusions about the yield of spot urine calcium measures. Fifth, we were unable to evaluate the yield of testing for several recommended laboratory tests[2, 3] that were not measured in the MrOS study.

In conclusion, we found that within a battery of laboratory tests recommended in men with osteoporosis, abnormalities of any test and of selected individual tests, such as vitamin D deficiency and abnormal kidney function, were common. However, other recommended tests were rarely present, and among all tests evaluated, only high alkaline phosphatase and vitamin D insufficiency were statistically significantly more frequent in those with versus those without osteoporosis. While results suggest that abnormalities of most recommended laboratory tests are unlikely to be risk factors for osteoporosis in older men, interventional studies still may be needed to determine whether targeted laboratory testing based on patient age, history and exam findings and correction of identified laboratory abnormalities will improve bone health.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: The Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Study is supported by National Institutes of Health funding. The following institutes provide support: the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), NIH Roadmap for Medical Research, and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) under the following grant numbers: U01 AG027810, U01 AG042124, U01 AG042139, U01 AG042140, U01 AG042143, U01 AG042145, U01 AG042168, U01 AR066160, UL1 TR000128, R01 HL071194, R01 HL070848, R01 HL070847, R01 HL070842, R01 HL070841, R01 HL070837, R01 HL070838, and R01 HL070839, and K23HL096832. CGL receives support from a VA Clinical Science Research and Development Career Development Award, Project number 5IK2CW000729–02. This material is also the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

Design and/or conduct of the study: Fink, Litwack-Harrison, Taylor, Bauer, Orwoll, Ensrud

Study guarantor: Fink, Orwoll, Ensrud

Collection of data: Orwoll, Ensrud

Analysis and/or interpretation of data: Fink, Litwack-Harrison, Taylor, Bauer, Orwoll, Lee, Barrett-Connor, Schousboe, Kado, Garimella, Ensrud

Preparation of the manuscript: Fink

Critical review and approval of the manuscript: Litwack-Harrison, Taylor, Bauer, Orwoll, Lee, Barrett-Connor, Schousboe, Kado, Garimella, Ensrud

Competing Interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: Drs. Fink, Taylor, Schousboe and Ensrud report grants from NIH during the conduct of the study. Dr. Schousboe also reports that he was principal investigator on a grant his employer (Park Nicollet Institute) received from Bone Ultrasound Finland Ltd. during the conduct of the study. Dr. Ensrud serves as a consultant on a Data Monitoring Committee for Merck Sharpe & Dohme. Dr. Orwoll reports grants and consulting fees from Merck & Company and Eli Lilly & Company during the conduct of the study. Dr. Lee reports a Career Development Award from VA Clinical Science Research and Development. Stephanie Litwack-Harrison, Douglas C. Bauer, Elizabeth Barrett-Connor, Deborah M. Kado, and Pranav S. Garimella declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Sponsor role: The funding agencies had no direct role in the conduct of the study; the collection, management, analyses and interpretation of the data; or preparation or approval of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Howard A. Fink, Geriatric Research Education & Clinical Center, Veterans Affairs Health Care System, Minneapolis, MN, USA. Center for Chronic Disease Outcomes Research, Veterans Affairs Health Care System, Minneapolis, MN, USA. Department of Medicine, and Division of Epidemiology and Community Health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA.

Stephanie Litwack-Harrison, San Francisco Coordinating Center, University of California, San Francisco, Department of Epidemiology & Statistics, San Francisco, CA, USA.

Brent C. Taylor, Center for Chronic Disease Outcomes Research, Veterans Affairs Health Care System, Minneapolis, MN, USA. Department of Medicine, and Division of Epidemiology and Community Health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA.

Douglas C. Bauer, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA.

Eric S. Orwoll, Research Service, Veterans Affairs Health Care System, Portland, OR, USA. Bone & Mineral Unit, Department of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, USA.

Christine G. Lee, Research Service, Veterans Affairs Health Care System, Portland, OR, USA. Bone & Mineral Unit, Department of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, USA.

Elizabeth Barrett-Connor, Department of Family Medicine & Public Health, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA.

John T. Schousboe, Health Research Center, Park Nicollet Institute for Research and Education, Minneapolis, MN, USA. Division of Health Policy & Management, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA.

Deborah M. Kado, Department of Family Medicine & Public Health, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA.

Pranav S. Garimella, Division of Nephrology, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA.

Kristine E. Ensrud, Center for Chronic Disease Outcomes Research, Veterans Affairs Health Care System, Minneapolis, MN, USA. Department of Medicine, and Division of Epidemiology and Community Health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA.

References

- 1.Ryan CS, Petkov VI, Adler RA. Osteoporosis in men: the value of laboratory testing. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:1845–1853. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1421-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watts NB, Adler RA, Bilezikian JP, Drake MT, Eastell R, Orwoll ES, Finkelstein JS, Endocrine S. Osteoporosis in men: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:1802–1822. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, Lewiecki EM, Tanner B, Randall S, Lindsay R. Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25:2359–2381. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-2794-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blank JB, Cawthon PM, Carrion-Petersen ML, Harper L, Johnson JP, Mitson E, Delay RR. Overview of recruitment for the osteoporotic fractures in men study (MrOS) ContempClin Trials. 2005;26:557–568. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orwoll E, Blank JB, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Design and baseline characteristics of the osteoporotic fractures in men (MrOS) study--a large observational study of the determinants of fracture in older men. ContempClin Trials. 2005;26:569–585. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pahor M, Chrischilles EA, Guralnik JM, Brown SL, Wallace RB, Carbonin P. Drug data coding and analysis in epidemiologic studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 1994;10:405–411. doi: 10.1007/BF01719664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Looker AC, Wahner HW, Dunn WL, Calvo MS, Harris TB, Heyse SP, Johnston CC, Jr, Lindsay R. Updated data on proximal femur bone mineral levels of US adults. OsteoporosInt. 1998;8:468–489. doi: 10.1007/s001980050093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Altman DG. Confidence intervals for the number needed to treat. BMJ. 1998;317:1309–1312. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7168.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deutschmann HA, Weger M, Weger W, Kotanko P, Deutschmann MJ, Skrabal F. Search for occult secondary osteoporosis: impact of identified possible risk factors on bone mineral density. Journal of internal medicine. 2002;252:389–397. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.01040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tannenbaum C, Clark J, Schwartzman K, Wallenstein S, Lapinski R, Meier D, Luckey M. Yield of laboratory testing to identify secondary contributors to osteoporosis in otherwise healthy women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:4431–4437. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eller-Vainicher C, Cairoli E, Zhukouskaya VV, Morelli V, Palmieri S, Scillitani A, Beck-Peccoz P, Chiodini I. Prevalence of subclinical contributors to low bone mineral density and/or fragility fracture. European journal of endocrinology/European Federation of Endocrine Societies. 2013;169:225–237. doi: 10.1530/EJE-13-0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jamal SA, Leiter RE, Bayoumi AM, Bauer DC, Cummings SR. Clinical utility of laboratory testing in women with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:534–540. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1718-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, Gass M, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of fractures. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:669–683. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]