Abstract

Objectives To determine whether assessment of all moderate-to-severe symptoms at baseline gives a more accurate evaluation of the treatment effect of ospemifene in vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) than the most bothersome symptom (MBS) approach.

Methods Data were pooled from two pivotal phase-III clinical trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of oral ospemifene 60 mg/day for the treatment of symptoms of VVA (n = 1463 subjects). Symptoms of vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and vaginal and/or vulvar irritation/itching reported as moderate or severe at baseline were evaluated. Clinically relevant differences between ospemifene and placebo were analyzed using a four-point severity scoring system and presented as improvement, substantial improvement, or relief.

Results Subjects in these studies reported statistically significant improvement, substantial improvement, and relief for vaginal dryness (p < 0.00001), dyspareunia (p < 0.001) and statistically significant improvement and relief for vaginal and/or vulvar irritation/itching (p < 0.01) from baseline to week 12 with ospemifene compared with placebo. A similar trend was observed for women who reported substantial improvement of vaginal and/or vulvar irritation/itching.

Conclusions For drug registration purposes, the use of the MBS model is appealing because of its simplicity and ease of scientific validation. However, the MBS model may underestimate the total magnitude of the clinical benefit of ospemifene treatment for symptomatic women suffering from VVA.

Keywords: Vulvar and vaginal atrophy, ospemifene, randomized clinical trials

Introduction

Vulvar and vaginal atrophy (VVA) is a chronic, progressive medical condition which affects the majority of postmenopausal women1–3. VVA is a consequence of the decline in estrogen levels during menopause and is associated with physiological changes of the vulval, vaginal, and urogenital epithelia. Such changes give rise to a number of genital and urinary symptoms. Genital symptoms include dryness, dyspareunia, itching, irritation, and burning, whereas urinary symptoms include urgency, increased frequency, nocturia, dysuria, accentuated incontinence, and recurrent urinary tract infections2 , 4. Symptoms can vary in severity, ranging from mild to severe discomfort, thus negatively impacting sexual health and quality of life2 , 5. By postmenopause, almost all women report at least one symptom, and most report five or more, with 50% of women experiencing vaginal discomfort attributable to VVA6–8. Despite the availability of several treatment options for VVA, satisfaction and compliance with available treatments are low, with many women citing long-term safety, lack of efficacy, and lack of convenience as reasons for dissatisfaction9. There is therefore a need for pharmacological treatment options that are convenient to use and that are able to treat the multiple symptoms associated with VVA.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has published guidance outlining the conduct of clinical studies for the treatment of VVA, specifying that a new product is required to demonstrate efficacy at three co-primary endpoints: namely a change in (1) maturation index (decrease in the percentage of parabasal vaginal cells and increase in the percentage of superficial vaginal cells); (2) vaginal pH; and (3) severity of the patient-reported most bothersome symptom (MBS), which are derived from a select list of symptoms scored by participants at baseline on a scale of 0–3 (0, none; 1, mild; 2, moderate; 3, severe)10.

Although the MBS metric may be simple in its approach, by using both a simple four-step severity scale and ensuring that each patient is only counted once, it does have some limitations. The use of a composite MBS score includes all treated participants in the analysis, but is a function of any combination of symptoms, and thus, symptom individuality is lost11. However, by evaluating each individual symptom as an MBS, a very selective patient population is created11, resulting in a substantial reduction in the number of patients included in the analysis12. In fact, when only one symptom per woman is considered, the treatment effect on approximately 60% of VVA symptoms is ignored11 , 12. Furthermore, many patients with VVA experience more than one moderate or severe symptom but are restricted to choosing only one symptom as their MBS. Therefore, the MBS metric may not permit a meaningful subgroup analysis for each individual symptom12. It has been proposed that a more meaningful approach to determine treatment efficacy may be to measure changes in all moderate-to-severe symptoms at baseline instead of the MBS, which will involve counting the number of symptoms rather than the number of patients12. Although patients who show multiple symptoms would be counted more than once, this approach may allow a more accurate evaluation of treatment effects.

To test this hypothesis, the current pooled analysis used data from two pivotal studies13–15 showing that treatment with ospemifene was consistently associated with greater clinically relevant improvements in the severity of the MBSs of vaginal dryness or dyspareunia compared with placebo. The objective of the analysis was to evaluate the clinical relevance of ospemifene treatment as defined by improvement, substantial improvement, or relief, of all moderate or severe symptoms of VVA at baseline, as has also been done for MBS5. The current analysis considered vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and vaginal and/or vulvar irritation/itching, as they are the three most common symptoms reported by women with VVA and are recommended for the assessment of efficacy of treatments for VVA10 , 12.

Methods

Patients and study design

The current analysis pooled data from two trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of oral ospemifene 60 mg/day compared with placebo for the treatment of symptoms of VVA in 1463 postmenopausal women13–15. The study designs and inclusion criteria are described in detail elsewhere13–15. Both studies were multicenter, randomized, double-blind, 12-week, phase-III studies in postmenopausal women aged 40–80 years with the following criteria of VVA: (1) 5% or less superficial cells on the vaginal smear (maturation index); (2) vaginal pH > 5.0; (3) at least one moderate or severe symptom of VVA (Study 310; NCT00276094)13, or moderate-to-severe vaginal dryness or dyspareunia (Study 821; NCT00729469)14 , 15. Both studies were designed to compare the effect of ospemifene versus placebo on the symptom that was selected by the patient as their MBS (co-primary endpoint), but also collected information on the severity of other VVA symptoms as a secondary endpoint14 , 15. As the secondary endpoints of all moderate or severe symptoms at baseline in both studies were collected in the same way, they were therefore combined for this analysis (Table 1)14 , 15.

Table 1.

Baseline frequency distribution of moderate-to-severe vulvovaginal atrophy symptoms included in this analysis and the most bothersome symptom (MBS) by treatment group.

|

Number of women (in Studies 310 and 821) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

60 mg ospemifene |

Placebo |

Total |

||||

| MBS | Moderate/severe | MBS | Moderate/severe | MBS | Moderate/severe | |

| Dryness | 278 | 676 | 258 | 656 | 536 | 1332 |

| Dyspareunia | 423 | 571 | 424 | 548 | 847 | 1119 |

| Vaginal and/or vulvar irritation/itching | – | 149 | – | 248 | – | 397 |

| Total | 1383 | 2848 | ||||

(–) denotes no data collected for that symptom

Both studies were approved by the institutional review board and ethics committee for each site and conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments, and Good Clinical Practice. All patients provided written informed consent before trial initiation. Symptom severity was measured using a four-point scoring system (none, 0; mild, 1; moderate, 2; and severe, 3); the mean changes from baseline, based on this scoring system for the co-primary endpoints of vaginal dryness and dyspareunia in each study, have been reported elsewhere13–15, as have the clinically meaningful differences between 60 mg ospemifene and placebo5.

Data analyses

The current analysis focused on patients who received either ospemifene 60 mg/day or placebo in both studies and includes a total of 1463 patients13–15. Analysis of clinically meaningful differences to the patient’s condition was assessed by the concepts of improvement, substantial improvement, or relief of symptoms in the 60-mg ospemifene group compared with placebo5 , 11.

Symptoms reported as moderate or severe at baseline in either study, which included vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and vaginal and/or vulvar irritation/itching, were selected for the present analysis. Efficacy analysis included the change from baseline to week 12 in the severity of symptoms: improvement was defined as a reduction in one or more units on the four-point severity scoring system5 , 11; substantial improvement was defined as a reduction in two or three units on the four-point severity scoring system, which, by default, only includes subjects who had moderate or severe symptoms at baseline, changing from severe to mild or none, and moderate to none5; and relief was defined as having a severity score at week 12 of mild or none (i.e. does not signify a change, but records the final score)5 , 11.

For missing values, the last observation carried forward (LOCF) was used. Improvement, relief, and substantial improvement were analyzed using the Fisher’s exact two-sided test.

Results

Distribution of symptoms

Approximately one-fifth of the women who received either ospemifene 60 mg/day or placebo (23.9% and 17.7%, respectively) reported only one moderate or severe symptom. Overall, 79.5% of women in both studies combined had more than one symptom (two symptoms: 47.3%; three symptoms: 23.5%; four symptoms: 7.1%) (Table 2). Of the 1332 women with moderate or severe vaginal dryness, 40.2% reported it as their MBS. Similarly, 75.7% of all women with moderate or severe dyspareunia selected it as their MBS. However, since vaginal and/or vulvar irritation/itching were not selected to be analyzed as an MBS, the effect of ospemifene on this symptom was not assessed via the MBS approach. It was also found that, between screening and randomization, approximately 20% of women changed their MBS selection. In total, in the current analysis the number of moderate or severe symptoms assessed more than doubled compared with the MBS approach (Table 1), as also described by other authors11 , 12.

Table 2.

Number of moderate-to-severe symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy reported by women at baseline. Data are given as n (%).

| Number of symptoms | Study 310a | Study 821b | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 6 (1.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (0.4%) |

| 1 | 130 (23.9%) | 163 (17.7%) | 293 (20.0%) |

| 2 | 252 (46.3%) | 440 (47.9%) | 692 (47.3%) |

| 3 | 113 (20.8%) | 231 (25.1%) | 344 (23.5%) |

| 4 | 33 (6.1%) | 71 (7.7%) | 104 (7.1%) |

| 5 | 10 (1.8%) | 14 (1.5%) | 24 (1.6%) |

| Total | 544 | 919 | 1463 |

aStudy 310 randomized patients to either ospemifene 30 mg/day, ospemifene 60 mg/day or placebo; only data for patients receiving ospemifene 60 mg/day or placebo are included for comparison with Study 821; bStudy 821 enrolled only patients with a most bothersome symptom of vaginal dryness or dyspareunia

Clinical relevance

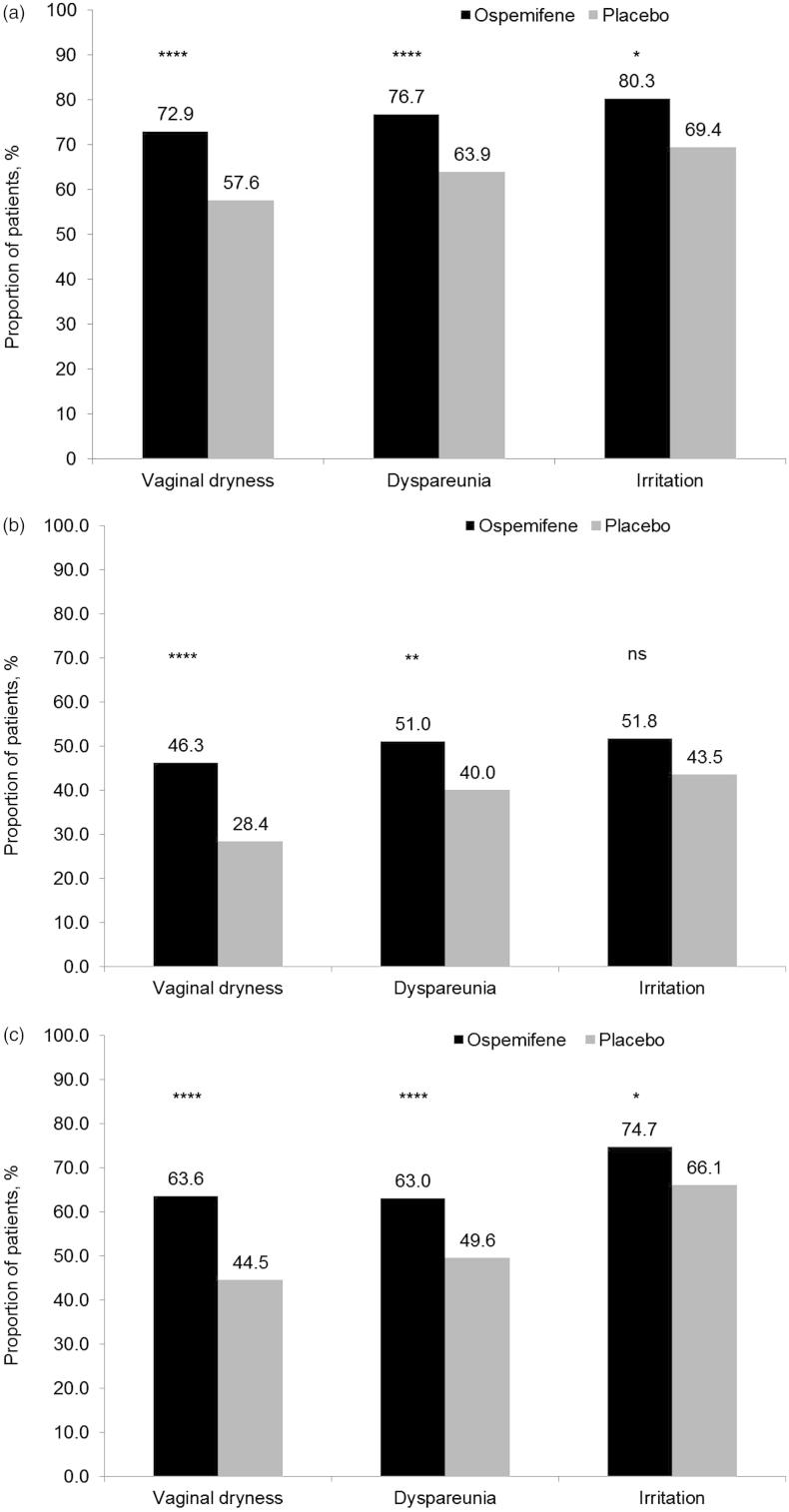

The clinical relevance of the change in severity of moderate or severe vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and vaginal and/or vulvar irritation/itching was assessed using definitions of improvement, substantial improvement, and relief (Figure 1). A significant proportion of subjects reported an improvement in the moderate or severe symptoms of vaginal dryness (72.9 vs. 57.6%; p < 0.00001), dyspareunia (76.7 vs. 63.9%; p < 0.00001), and vaginal and/or vulvar irritation/itching (80.3 vs. 69.4%; p = 0.0053) from baseline to week 12 with ospemifene compared with placebo (Figure 1a). A significant proportion of women reported a substantial improvement in vaginal dryness (46.3 vs. 28.4%; p < 0.00001) and dyspareunia (51.0 vs. 40.0%; p = 0.0002), and a trend was seen for vaginal and/or vulvar irritation/itching (51.8 vs. 43.5%; p = 0.0726) (Figure 1b). Similarly, a significant proportion of subjects reported relief for all three symptoms: vaginal dryness (63.6 vs. 44.5%; p < 0.00001), dyspareunia (63.0 vs. 49.6%; p = 0.0002), and vaginal and/or vulvar irritation/itching (74.7 vs. 66.1%; p = 0.0393) from baseline to week 12 with ospemifene compared with placebo (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Clinically relevant differences in the treatment of moderate or severe vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and vaginal and/or vulvar irritation/itching as assessed by (a) improvement, (b) substantial improvement, and (c) relief, in a pooled analysis of Studies 310 and 821. p Values for treatment comparisons (ospemifene 60 mg/day vs. placebo) from Fisher’s exact two-sided test. Improvement was defined as a reduction in one or more units on the four-point severity scoring system (this includes patients whose baseline score changed from severe to none, mild or moderate, from moderate to mild or none, and from mild to none). Substantial improvement was defined as a reduction in two or three units on the four-point severity scoring system (this includes patients whose baseline score changed from severe or moderate to none, or from severe to mild). Relief was defined as having a severity score at week 12 of mild or none (i.e. does not signify a change, but records the final score). ****p < 0.00001; ***p < 0.0001; **p < 0.001; *p < 0.05; ns, not significant.

Discussion

The current analysis showed that the clinical relevances of VVA treatment were similar for moderate and severe symptoms whether they were assessed by pooling all symptoms or using the MBS method. Guidance from the FDA requires that women enrolled in investigational studies report the effect of a treatment on one symptom of VVA, their MBS10. The current analysis also confirmed that, by using the MBS approach, the effect of treatment on half of VVA symptoms is not taken into consideration, as previously shown by others11 , 12.

The MBS approach has some limitations, given that a patient’s choice of MBS may change over time, as reported in the current analysis. Because the MBS may be selected from several of an individuals’ moderate or severe symptoms, different patients may choose a different symptom as their MBS despite similar severity. A moderate or severe symptom that is chosen by one patient as her MBS may not have the same weight for another patient. Since the a priori distribution of women entering any given trial with each symptom selected as the MBS cannot be known, this poses statistical challenges, and information regarding effects on less commonly selected symptoms cannot be determined due to the small subgroup sample size1. Considering the effect of all moderate or severe symptoms at baseline may therefore be more informative. The simplicity of the MBS approach in measuring only one symptom per subject is attractive as it avoids ‘double-counting’ of trial subjects. However, it does not take into account those women with more than one severe troubling symptom at baseline.

The way that VVA symptoms are assessed is particularly relevant for clinical practice as postmenopausal women with VVA often experience multiple symptoms4 , 16 and several of these may be self-rated as moderate to severe. The current analysis was the first of its kind to assess the effect of ospemifene on all moderate or severe symptoms of VVA for all patients in the study. It is important to note that a substantial placebo response was observed for some of the outcomes (up to 69.4%). Although large placebo responses are not uncommon in studies with patient-reported outcomes as endpoint, in the current data set the change from baseline in the placebo group may have been partly due to the use of a non-hormonal lubricant, provided for use as needed throughout the studies. Despite a decrease in lubricant use in the ospemifene group from baseline compared with the placebo group13–15, ospemifene 60 mg still resulted in a statistically significant difference with placebo in eight out of nine analyses. The analysis of all moderate or severe symptoms of vaginal dryness and dyspareunia at baseline was consistent with prior evidence that showed the effectiveness of ospemifene 60 mg/day in the treatment of VVA, as assessed by the MBS approach5. It demonstrates consistency in the effect of ospemifene 60 mg/day in the postmenopausal VVA population.

Additionally, the current pooled analysis assessing the clinical relevance of ospemifene on symptoms of VVA confirms the robustness of the MBS approach for all moderate or severe symptoms of VVA at baseline. For drug registration purposes, the use of the MBS model is appealing because of its simplicity and ease of scientific validation, as shown in the current study. Nevertheless, the MBS model may underestimate the total magnitude of the clinical benefit to symptomatic women. Therefore, we suggest using the two models concurrently in clinical trials to maximize the information on a product for prescribers.

Conclusion

Ospemifene 60 mg/day consistently showed a greater improvement, substantial improvement, or relief than placebo at baseline for all moderate or severe symptoms of vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and vaginal and/or vulvar irritation/itching. Although for drug registration purposes the MBS model is required, both models should be used in clinical trials to maximize information on the product to aid prescribers. Well-planned studies, utilizing an assessment of the effect of treatment on a broad range of moderate-to-severe symptoms of VVA, will provide a more comprehensive assessment of drug efficacy, with the ultimate aim being to minimize and manage symptoms, and improve quality of life in women undergoing menopause.

Conflict of interest

NB is a consultant working for Shionogi Ltd. during the past 2 years.

REN has had financial relationships (lecturer, member of advisory boards, and/or consultant) with Bayer-Schering Pharma, Ely Lilly, Gedeon-Richter, HRA Pharma, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer Inc., Shionogi Ltd, and Teva/Theramex.

During the past 2 years CC-B has had financial relationships (lecturer, member of advisory boards, and/or consultant) with Amgen, Pierre-Fabre, Servier, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Isdin, Pfizer Inc., and Shionogi Ltd.

During the past 2 years TdeV has had financial relationships (lecturer, member of advisory boards, and/or consultant) with Bayer-Schering Pharma, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Pfizer Inc., Amgen, and Abbott.

JAS has served (within the last year) or is currently serving as a consultant to, or on the advisory boards of, AbbVie, Inc., Actavis, PLC, Amgen Inc, Amneal Pharmaceuticals, Apotex, Inc, Ascend Therapeutics, Depomed, Inc, Everett Laboratories, Inc, Lupin Pharmaceuticals, Meda Pharmaceuticals Inc, Merck & Co, Inc, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Noven Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer Inc, Shionogi Inc, Shippan Point Advisors LLC, Sprout Pharmaceuticals, TherapeuticsMD, and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. In the last year he has received or is currently receiving grant/research support from AbbVie, Inc, Actavis PLC, Bayer Healthcare LLC, EndoCeutics Inc, Novo Nordisk, Novogyne, Palatin Technologies, and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. He has also served or is currently serving on the speakers’ bureaux of Amgen Inc, Eisai, Inc, Merck, Noven Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Shionogi Inc, and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. JAS was the Chief Medical Officer for Sprout Pharmaceuticals until 4 January 2013.

Source of funding

The preparation of this manuscript was supported by Shionogi Ltd. All authors take full responsibility for the content of the article. Editorial assistance was provided by Apothecom Scopemedical Ltd and supported by Shionogi Ltd.

References

- Freedman M, Kaunitz AM, Reape KZ, Hait H, Shu H. Twice-weekly synthetic conjugated estrogens vaginal cream for the treatment of vaginal atrophy. Menopause. 2009;16:735–41. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318199e734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nappi RE, Mattsson L-Å, Lachowsky M, Maamari R, Giraldi A. The CLOSER survey: impact of postmenopausal vaginal discomfort on relationships between women and their partners in Northern and Southern Europe. Maturitas. 2013;75:373–9. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parish SJ, Nappi RE, Krychman ML.et alImpact of vulvovaginal health on postmenopausal women: a review of surveys on symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy. Int J Womens Health 20135437–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacBride MB, Rhodes DJ, Shuster LT. Vulvovaginal atrophy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:87–94. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nappi RE, Panay N, Bruyniks N, Castelo-Branco C, de Villiers TJ, Simon JA. The clinical relevance of the effect of ospemifene on symptoms of vulvar and vaginal atrophy. Climacteric. 2015;18:233–40. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2014.975199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nappi RE, Palacios S. Impact of vulvovaginal atrophy on sexual health and quality of life at postmenopause. Climacteric. 2014;17:3–9. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2013.871696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennerstein L, Dudley E, Hopper J, Guthrie J, Burger H. A prospective population-based study of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:351–8. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00930-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber MA, Limpens J, Roovers JPWR. Assessment of vaginal atrophy: a review. Int Urogynecology J. 2015;26:15–28. doi: 10.1007/s00192-014-2464-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsberg SA, Wysocki S, Magnus L, Krychman ML. Vulvar and vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: findings from the REVIVE (REal Women’s VIews of Treatment Options for Menopausal Vaginal ChangEs) survey. J Sex Med. 2013;10:1790–9. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidance for Industry: Estrogen and Estrogen/Progestin Drug Products to Treat Vasomotor Symptoms and Vulvar and Vaginal Atrophy Symptoms – Recommendations for Clinical Evaluation. Draft guidance, Food and Drug Administration. January 2003. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm071643.pdf [Last accessed July 2015]

- Ettinger B, Hait H, Reape KZ, Shu H. Measuring symptom relief in studies of vaginal and vulvar atrophy: the most bothersome symptom approach. Menopause. 2008;15:885–9. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318182f84b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Ng M-J, van der Vlugt TH, Price PH, Orencia A. Statistical considerations for the efficacy assessment of clinical studies of vulvar and vaginal atrophy. Drug Inf J. 2010;44:581–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann GA, Komi JO, Ospemifene Study Group. Ospemifene effectively treats vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: results from a pivotal phase 3 study. Menopause. 2010;17:480–6. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181c1ac01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portman DJ, Bachmann GA, Simon JA, Ospemifene Study Group. Ospemifene, a novel selective estrogen receptor modulator for treating dyspareunia associated with postmenopausal vulvar and vaginal atrophy. Menopause. 2013;20:623–30. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318279ba64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portman D, Palacios S, Nappi RE, Mueck AO. Ospemifene, a non-oestrogen selective oestrogen receptor modulator for the treatment of vaginal dryness associated with postmenopausal vulvar and vaginal atrophy: a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. Maturitas. 2014;78:91–8. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein I, Dicks B, Kim NN, Hartzell R. Multidisciplinary overview of vaginal atrophy and associated genitourinary symptoms in postmenopausal women. Sex Med. 2013;1:44–53. doi: 10.1002/sm2.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]