Abstract

Purpose

This study evaluated the incidence of imatinib-associated skin rash, the interventional outcomes of severe rash, and impact of severe rash on the outcomes of imatinib treatment in gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) patients.

Materials and Methods

A total of 620 patients were administered adjuvant or palliative imatinib for GIST at Asan Medical Center between January 2000 and July 2012. This analysis focused on a group of 42 patients who developed a severe rash requiring major interventions, defined as dose interruption or reduction of imatinib or systemic steroid use.

Results

Of the 620 patients treated with imatinib, 148 patients (23.9%) developed an imatinib-associated skin rash; 42 patients (6.8%) developed a severe rash requiring major intervention. Of these, 28 patients (66.8%) successfully continued imatinib with interventions. Serial blood eosinophil levels during imatinib treatment were associated with skin rash and severity. A significant association was observed between successful intervention and blood eosinophil level at the time of intervention initiation. In metastatic settings, patients with severe rash requiring major interventions tended to show poorer progression-free survival than patients who did not require major intervention and patients with no rash, although this finding was not statistically significant (p=0.326).

Conclusion

By aggressive treatment of severe rash through modification of imatinib dose or use of systemic steroid, the majority of patients can continue on imatinib. In particular, imatinib dose intensity can be maintained with use of systemic steroid. Measuring the blood eosinophil levels may be helpful in guiding the management plan for skin rash regarding the intensity and duration of interventions.

Keywords: Imatinib, Gastrointestinal stromal tumors, Exanthema, Eosinophils, Treatment outcome

Introduction

The introduction of imatinib mesylate—a small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) active against c-KIT, BCRABL, and platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA)—has led to dramatically improved clinical outcomes of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) patients [1-5]. Although clinical benefits of other TKIs, such as sunitinib and regorafenib, have also been demonstrated, imatinib remains the cornerstone of treatment for GIST in both adjuvant and palliative settings [4-8]. Current treatment guidelines recommend long-term continuous imatinib therapy in advanced GIST patients, as long as clinical benefits are maintained, because rapid disease progression often occurs following treatment interruption [9-11]. Likewise, adjuvant imatinib should be administered to high-risk GIST patients for ≥ 36 months [5]. For patients receiving long-term imatinib treatment, maintaining the continued administration at a sufficient dose is critical for maintaining the clinical effectiveness of imatinib [11,12].

Imatinib is generally well tolerated and most adverse events are mild and can be managed without dose reduction or treatment interruption [2-5]; however, some patients experience severe toxicity which may result in reduced patient compliance and dose intensity. Considering the importance of maintaining sufficient daily imatinib dosing in order to achieve optimal clinical outcomes, proper management of imatinib-associated adverse events is crucial [11,12]. Skin rash commonly presenting as erythematous and maculopapular lesions is one of the most troublesome toxicities, which may affect imatinib compliance or persistence. It affects up to one-third of GIST patients receiving imatinib with grade 3/4 up to 10% [2-4]. The treatment options for imatinib-related rash described in the medical literature are based on case reports, case series, and reported personal experiences. However there are few data on the effectiveness of these treatments or the clinical outcomes of patients with severe skin rash.

We thus conducted this retrospective study using data retrieved from our database between 2000 and 2012 to evaluate (1) the incidence of skin rash in GIST patients administered imatinib, (2) therapeutic interventions for severe skin rash and outcomes, and (3) the impact of skin rash on imatinib treatment outcomes.

Materials and Methods

1. Study population and treatment

A total of 1,392 patients were entered into the GIST prospective database at the Asan Medical Center in Korea between January 2000 and July 2012. Of these, 620 adult patients were treated with imatinib in adjuvant or palliative settings for histologically proven GIST (entire cohort). This analysis focused on a group of 42 patients who developed severe skin rash requiring major interventions defined as interruption or dose reduction of imatinib and/or systemic steroid use (group 1). Anti-histamine agents and/or topical steroids were also administered at the discretion of the attending physicians. Severity of skin rash was classified as “mild to moderate,” corresponding to grade 1 to 2 (macular or popular eruption or erythema without associated symptoms and with pruritus covering < 50% of body surface area, respectively), or “severe,” corresponding to grade 3 (symptomatic generalized erythroderma or macular, papular, or vesicular eruption or desquamation covering > 50% of body surface area) to 4 (generalized exfoliative dermatitis or ulcerative dermatitis). The success of each intervention for severe rash was defined as continuation of imatinib without the persistence or recurrence of severe rash requiring further intervention. The overall success rate of the entire clinical course was analyzed regardless of the number of interventions, and patients who had to permanently discontinue imatinib due to rash at the first occurrence were also considered treatment failures.

The clinical features and treatment outcomes of the patients with severe imatinib-associated skin rash (group 1) were compared with those of two comparator groups from the entire cohort. One was composed of 106 GIST patients who received imatinib during the same time period as group 1 and developed mild to moderate skin rash not requiring major interventions (group 2), and the other consisted of 100 consecutive patients in the order of being recently diagnosed who had not developed skin rash and had available clinical data (group 3). All patients from these three groups were included in the analysis for blood eosinophil counts during imatinib treatment, and only patients treated with imatinib 400 mg/day for unresectable or metastatic GIST were included in the analysis for treatment outcomes. Patients administered palliative imatinib due to tumor perforation that occurred before or during surgery for localized disease were excluded from the progression-free survival (PFS) analysis.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center. All information was obtained with the appropriate Institutional Review Board waivers.

2. Statistical analysis

Pearson’s chi-square and Fisher exact tests were used for comparison of discrete data as required, and the Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance tests were used for comparison of non-parametric variables when two or three categories were included, respectively. PFS was calculated from the date imatinib was started for advanced GIST to the date of disease progression or death due to any cause, whichever occurred first. Survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test was used to determine the significance of any differences in the survival curves. All tests were two-sided, and p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

1. Patient characteristics

Of the 620 study patients treated with imatinib, 148 patients (23.9%) developed skin rash during imatinib treatment with 42 patients (6.8%) having a severe skin rash requiring major interventions. The characteristics of these 42 patients are shown in Table 1. Imatinib was administered in the setting of neoadjuvant, adjuvant, and palliative treatment in eight patients (19.0%), 11 patients (26.2%), and 23 patients (54.8%), respectively. The median time to development of severe skin rash requiring major interventions was 2.8 months (range, 0.2 to 8.4 months).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (n=42)

| Characteristic | No. of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 20 (47.6) |

| Female | 22 (52.4) |

| Median age (range, yr) | 63 (30-81) |

| Treatment setting of imatinib | |

| Neoadjuvant | 8 (19.0) |

| Adjuvant | 11 (26.2) |

| Palliative | 23 (54.8) |

| Imatinib dose at the time of skin rash (mg) | |

| 800 | 1 (2.4) |

| 600 | 1 (2.4) |

| 400 | 38 (90.5) |

| 300 | 2 (4.8) |

| Grade of skin rash | |

| 3 | 40 (95.2) |

| 4 | 2 (4.8) |

2. Interventions for severe imatinib-associated skin rash

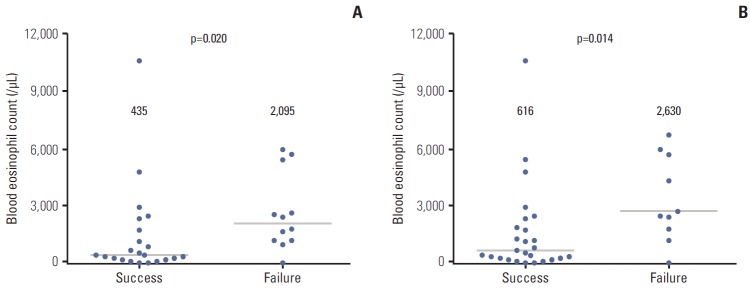

Two patients (4.8%) had to permanently discontinue imatinib due to a grade 3 or 4 skin rash, respectively. Major interventions for skin rash were administered in the remaining 40 patients, including systemic steroids only (n=17, 40.5%), imatinib dose modification only (dose reduction only [n=6, 14.3%], dose interruption only [n=2, 4.8%], dose reduction+ interruption [n=6, 14.3%]), or the combined use of systemic steroids and imatinib dose modification (steroids+dose reduction [n=2, 4.8%], steroids+interruption [n=3, 7.1%], steroids+dose reduction+interruption [n=4, 9.5%]). The median dose and duration of initial steroid treatment before tapering were 20 mg/day prednisolone (range, 5 to 60 mg/day) and 7 days (range, 4 to 28 days), respectively, then the treatment was tapered off with a median total duration of steroid of 28 days (range, 7 to 204 days). The first intervention was successful in 22 patients (55.0%), but it failed in 14 patients (35.0%). Four patients (10.0%) who had discontinued imatinib early due to adverse events other than rash (n=2), disease progression (n=1), or GIST resection (n=1) could not be evaluated for interventional efficacy. Of 14 patients whose first intervention failed, three patients (21.4%) discontinued imatinib due to uncontrolled severe rash and a second intervention was administered in the remaining 11 patients (78.6%); only systemic steroids (n=6, 42.9%), imatinib dose modification (n=2, 14.3%; dose reduction and interruption in each one), and systemic steroids+imatinib dose modification (steroids+imatinib reduction [n=1, 7.1%], steroids+imatinib interruption [n=2, 14.3%]). Second interventions were successful (n=4, 36.4%), failed (n=6, 54.5%), or not evaluable (n=1, 9.1%). Of six patients whose second intervention failed, two patients (33.2%) discontinued imatinib and a third intervention was administered in the remaining four patients: systemic steroids (n=1, 25.0%), imatinib dose reduction (n=1, 25.0%), or steroids imatinib dose reduction (n=2, 50.0%). The third intervention was successful in two patients (50.0%) and failed in the other two patients (50.0%). A summary of the interventions and results is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Major interventions for rash and outcomes in patients with imatinib-associated severe skin rash.

In summary, one intervention for skin rash was administered in 29 patients (69.0%), two interventions in seven patients (16.7%), and three interventions in four patients (9.5%). Interventions were successful over the entire clinical course in 28 patients (66.8%) who were able to maintain imatinib without permanent discontinuation due to skin rash with a dose of 800 mg/day (n=1), 400 mg/day (n=19), 300 mg/day (n=5), or 200 mg/day (n=3).

Toxicity requiring medical treatment, which was possibly related to the administration of steroids as an intervention for skin rash consisted of hyperglycemia aggravation in patients with preexisting diabetes mellitus (n=2).

Of note, patients administered systemic steroids for rash tended to maintain a higher imatinib dose intensity than patients who did not (median relative dose intensity at 6 months, 1.00 vs. 0.79, respectively; p=0.122)

3. Factors associated with successful interventions for severe skin rash

No association was observed between the outcomes of the first intervention and clinical factors (e.g., sex, age), and the nature of the interventions, including types of intervention (e.g., imatinib dose modification, systemic steroid use—starting dose, duration of starting or tapering dose) (Table 2). These factors were also not associated with the interventional outcomes of the overall clinical course (data not shown).

Table 2.

Factors associated with success of the first major interventions for severe skin rash (n=36)

| Factor | No. of patients with success (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 11/17 (64.7) | 0.676 |

| Female | 11/19 (57.9) | |

| Age (yr) | ||

| < 65 | 13/20 (65.0) | 0.593 |

| ≥ 65 | 9/16 (56.3) | |

| Type of major intervention | ||

| Systemic steroid only | 7/15 (46.7) | 0.384 |

| Imatinib dose modification | 9/13 (69.2) | |

| Systemic steroid+imatinib dose modification | 6/8 (75.0) | |

| Starting dose of steroid (mg/day) | ||

| < 15 | 4/7 (57.1) | 0.685 |

| 15-30 | 4/9 (44.4) | |

| ≥ 30 | 5/7 (71.4) | |

| Duration of steroid starting dose (wk) | ||

| < 1 | 3/6 (50.0) | 0.331 |

| 1-2 | 7/9 (77.8) | |

| 2-3 | 1/4 (25.0) | |

| 3-4 | 2/3 (66.7) | |

| 4-8 | 0/1 (0) | |

| Starting dose and duration of steroid | ||

| < 15 mg/day for less than 1 week | 0/1 (0) | 0.573 |

| < 15 mg/day for ≥ 1 week | 4/6 (66.7) | |

| ≥ 15 mg/day for less than 1 week | 1/3 (33.3) | |

| ≥ 15 mg/day for ≥ 1 week | 8/13 (61.5) | |

| Duration of steroid tapering (wk) | ||

| No tapering | 6/7 (85.7) | 0.173 |

| < 1 | 0/1 (0) | |

| 1-2 | 3/4 (75.0) | |

| 2-3 | 1/3 (33.3) | |

| 3-4 | 0/1 (0) | |

| 4-8 | 0/2 (0) | |

| ≥ 8 | 3/5 (60.0) | |

| Blood eosinophil counts at initiation of interventions (/μL) | ||

| < 500 | 12/13 (92.3) | 0.011 |

| ≥ 500 | 10/21 (47.6) |

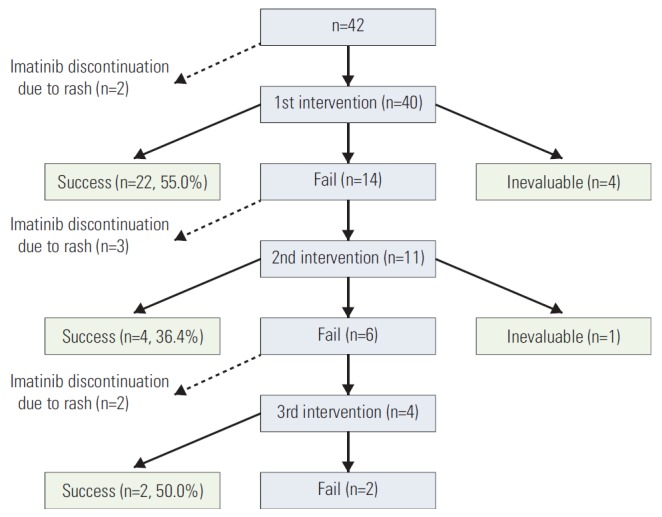

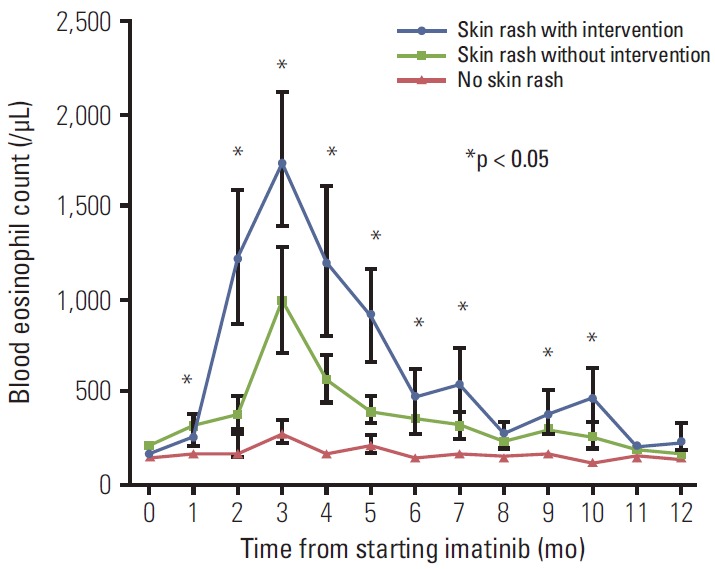

However, a significant association was observed between successful intervention and the blood eosinophil level at the time intervention was initiated. Among 34 patients for whom the blood eosinophil level at the time of intervention was available, the first intervention was successful in 92.3% (12 of 13) of patients with eosinophils < 500/μL, but was only successful in 47.6% (10 of 21) of patients with eosinophils ≥ 500/μL (p=0.011) (Table 2). In addition, the success rate was 93.8% (15 of 16) in patients with eosinophils < 1,000/μL compared with 38.9% (7 of 18) in patients with ≥ 1,000/μL (p=0.001). The final success rates for the overall clinical course were 92.3% (12 of 13) in patients with eosinophils < 500/μL vs. 60.9% (14 of 23) in patients with ≥ 500/μL (p=0.060), and 93.8% (15 of 16) in patients with eosinophils < 1,000/μL vs. 55.0% (11 of 20) in patients with ≥ 1,000/μL (p=0.022). Lower eosinophil counts were observed in patients with successful interventions compared to patients whose treatments failed; the median eosinophil count was 435/μL vs. 2,095/μL for the first intervention (p=0.020), and 616/μL vs. 2,630/μL for the overall clinical course (p=0.014) (Fig. 2). In addition, serial blood eosinophil levels during imatinib treatment showed association with the development of skin rash and its severity. Higher eosinophil levels in peripheral blood were significantly more likely to be shown in patients who developed imatinib-associated skin rash, particularly those with higher severity (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Association between blood eosinophil count and therapeutic outcomes of the first major interventions for severe skin rash (A) and final outcomes for all major interventions (B). Lines indicate median values.

Fig. 3.

Serial eosinophil counts in peripheral blood samples during the first year of imatinib treatment in patients with severe skin rash requiring major interventions (group 1), patients with skin rash not requiring major interventions (group 2), and patients without skin rash (group 3). Lines indicate the mean±standard error. *p < 0.05 (Kruskal-Wallis test).

4. Survival outcomes according to skin rash

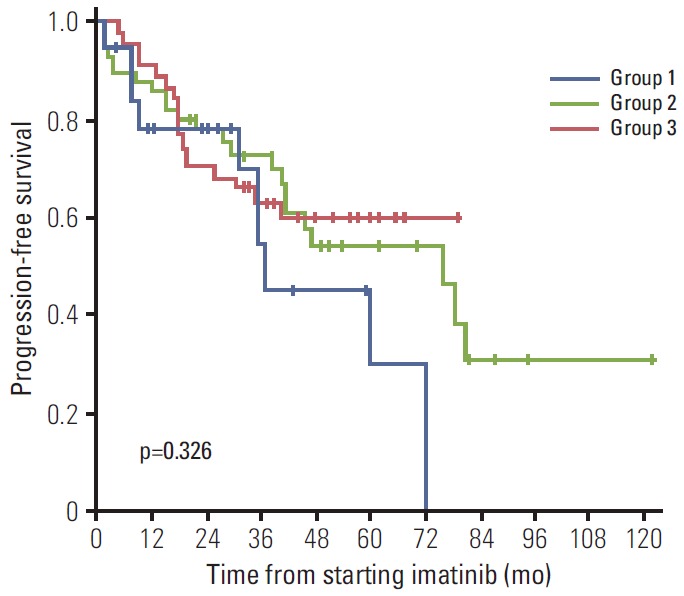

To determine the influence of skin rash and interventions on imatinib treatment outcomes, PFS was compared among patients with unresectable or metastatic GIST from three groups (group 1, skin rash requiring major intervention; group 2, skin rash not requiring major intervention; group 3, no skin rash). There were no significant differences in the baseline characteristics between groups, including age, sex, site of the primary tumor and metastasis, tumor size, tumor mutational status in c-KIT and PDGFRA, and baseline laboratory values (hemoglobin, granulocyte count, albumin, etc.) (Table 3). The median follow-up period was 55.9 months (range, 13.7 to 143.0 months) for group 1, 45.0 months (range, 14.3 to 145.4 months) for group 2, and 52.0 months (range, 14.3 to 80.8 months) for group 3. Group 1 tended to show a poorer PFS compared with groups 2 and 3 (p=0.326) (Fig. 4). As expected, actual dose intensity was significantly lower in group 1 compared with the other two groups: median relative dose intensity at 6 months was 0.88 (range, 0.61 to 1.00) for group 1 vs. 1.00 (range, 0.50 to 1.00) for group 2 vs. 1.00 (range, 0.78 to 1.00) for group 3 (p=0.0002).

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics of patients treated with imatinib for unresectable or metastatic GIST

| Factor | Group 1 (n=20) | Group 2 (n=58) | Group 3 (n=46) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, male | 8 (40.0) | 33 (56.9) | 28 (60.9) | 0.282 |

| Age (yr) | 64 (42-81) | 58 (37-75) | 58 (32-80) | 0.464 |

| Primary tumor site | ||||

| Small bowel | 9 (45.0) | 28 (48.3) | 19 (41.3) | 0.957 |

| Stomach | 8 (40.0) | 23 (39.7) | 21 (45.7) | |

| Others | 3 (15.0) | 7 (12.1) | 6 (13.0) | |

| Primary tumor size (cm)a) | ||||

| < 5 | 9 (45.0) | 18 (31.0) | 16 (34.8) | 0.787 |

| 5-10 | 5 (25.0) | 13 (22.4) | 12 (26.1) | |

| > 10 | 2 (10.0) | 14 (24.1) | 11 (23.9) | |

| Resected | 4 (20.0) | 13 (22.4) | 7 (15.2) | |

| Liver metastasis | 13 (65.0) | 38 (65.5) | 30 (65.3) | > 0.999 |

| Peritoneal metastasis | 7 (35.0) | 28 (48.3) | 20 (44.4) | 0.581 |

| Kinase mutation | ||||

| Kit exon 11 | 14 (70.0) | 41 (70.7) | 28 (60.9) | 0.243 |

| Wild or other mutation | 3 (15.0) | 12 (20.7) | 16 (34.8) | |

| Unknown | 3 (15.0) | 5 (8.6) | 2 (4.3) | |

| Neutrophil (/μL) | 3,265 (1,672-7,420) | 3,550 (1,512-14,250) | 3,790 (1,250-6,480) | 0.883 |

| White blood cell (/μL) | 6,000 (3,800-19,100) | 6,510 (3,200-17,400) | 6,150 (2,780-8,900) | 0.922 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.3 (9.2-17.5) | 12.4 (6.6-16.6) | 12.0 (8.0-16.1) | 0.818 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.9 (2.7-4.5) | 3.9 (2.8-4.8) | 3.9 (2.9-4.7) | 0.872 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.7 (0.4-1.5) | 0.7 (0.4-8.6) | 0.8 (0.1-2.3) | 0.833 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.9 (0.6-1.3) | 0.8 (0.5-1.2) | 0.9 (0.5-1.7) | 0.299 |

Values are presented as number (%) or median (range). Group 1, patients with severe skin rash requiring major intervention; group 2, patients with skin rash not requiring major intervention; group 3, patients without skin rash.

Primary tumor size indicates the longest tumor diameter of primary tumor present at the time of imatinib initiation while cases in which primary tumors were resected are shown as “resected."

Fig. 4.

Progression-free survival curves of patients with severe skin rash requiring major interventions (group 1), patients with skin rash not requiring major interventions (group 2), and patients without rash (group 3) while receiving imatinib for unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor.

Discussion

Skin rash is a well-recognized side effect of imatinib; however, insufficient evidence-based data are available for establishing treatment guidelines. In practice, antihistamines, topical lotions, and steroids are used in management of mild to moderate skin rash with imatinib, and for severe skin rash, the imatinib dose can be interrupted or reduced and short-term systemic steroids are frequently administered. However, the effectiveness of these interventions for controlling severe skin rash is largely unknown, and the predictive factors for interventional outcomes remain unknown. In addition, given the critical role of imatinib dose intensity in long-term treatment outcomes and possible adverse impact of systemic steroid on antitumor immunity in patients with GIST, further evaluations are needed to determine whether patients who receive these major interventions for severe skin rash show unfavorable clinical outcomes of imatinib.

In the current study, the overall incidence of skin rash was 23.9% and 6.8% of patients developed grade 3/4 severe rash during imatinib treatment, which is consistent with previous studies [2-4]. Major interventions for severe skin rash, including dose interruption or reduction of imatinib, or systemic steroid were successful in 66.7% of patients who were able to continue imatinib without recurrence of severe skin rash. Most patients (89.3%, 25 of 28) were able to maintain ≥ 300 mg/day imatinib. Although study limitations, including the small number of patients and its retrospective design, preclude the determination of optimal interventions, we believe that the proper use of interventions enables the continued administration of imatinib in most patients who develop severe skin rash. The continuation of therapeutic doses of imatinib has important implications regarding the efficacy of imatinib. Along with clinical and genetic factors, including baseline hemoglobin and granulocyte counts, albumin level, sex, primary tumor site, tumor size, and c-KIT and PDGFRA mutational status [3,13], systemic exposure to imatinib reportedly influences clinical outcomes. In advanced GIST patients, low plasma exposure (plasma trough concentrations [Cmin] < 1,100 ng/mL) is associated with a worse objective benefit rate and time to progression, suggesting that low steady-state plasma imatinib levels might contribute to drug failure [12]. Because severe skin rash occurs very early in the imatinib treatment course, as reported here (median, 2.8 months), reduction of imatinib dose due to severe rash may considerably decrease the overall dose intensity. Indeed, in advanced GIST, patients with severe skin rash requiring major interventions showed lower imatinib dose intensity, and tended to show a poorer PFS than patients with rash not requiring major interventions or patients without skin rash. Given that patients administered systemic steroids for rash had higher imatinib dose intensity than patients who did not, further studies are required to determine whether more aggressive systemic steroids with an optimal dose and duration could minimize dose interruption or reduction of imatinib due to rash, and improve imatinib treatment outcomes.

The pathophysiology of imatinib-associated skin reactions is unclear. The high prevalence and dose relationship suggest that skin rash may be related to the pharmacological effects of imatinib―blockade of c-KIT, which is normally present in the skin, rather than hypersensitivity [14]. However, the activation of immune mechanisms also seems to be involved in imatinib-associated skin rash. The predominant infiltration of CD8+ T-lymphocytes and enhanced interleukin (IL)-18 and IL-1β was reported in drug eruption caused by imatinib [15]. Of note, in our current analyses we found an association of the blood eosinophil level during imatinib treatment with skin rash, severity, and the outcomes of major interventions for severe rash. Eosinophils are important effector cells which promote tissue inflammation and induce tissue damage in a wide variety of disorders via the release of toxic granule proteins, lipid mediators, cytokines, and chemokines [16]. The increased number of eosinophils in patients with skin rash suggests that these cells may be involved in amplifying the underlying inflammatory and/or immune response in imatinib-induced rash. Because of the higher failure rate of interventions observed here, more aggressive interventions should be considered for patients with high levels of eosinophils at the time of severe rash. In addition, monitoring eosinophil levels to direct interventions in terms of intensity and duration could be useful for reducing recurrence and the exacerbation of skin rash during or after interventions.

Conclusion

Our current findings indicate that aggressive treatment of severe skin rash by dose interruption or reducing imatinib or systemic steroids can result in good clinical outcomes in terms of imatinib continuation in most GIST patients. There is now a need to establish a management strategy for skin rash including optimal steroid use for maintenance of imatinib dose intensity, and to validate the role of blood eosinophil levels in order to direct these treatments and ultimately achieve optimal clinical efficacy of imatinib.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI14C0198).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest relevant to this article was not reported.

References

- 1.Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Blanke CD, Van den Abbeele AD, Eisenberg B, Roberts PJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of imatinib mesylate in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:472–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verweij J, Casali PG, Zalcberg J, LeCesne A, Reichardt P, Blay JY, et al. Progression-free survival in gastrointestinal stromal tumours with high-dose imatinib: randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1127–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanke CD, Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Heinrich MC, Eisenberg B, Fletcher JA, et al. Long-term results from a randomized phase II trial of standard-versus higher-dose imatinib mesylate for patients with unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors expressing KIT. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:620–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.4403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dematteo RP, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, Maki RG, Pisters PW, Demetri GD, et al. Adjuvant imatinib mesylate after resection of localised, primary gastrointestinal stromal tumour: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1097–104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60500-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joensuu H, Eriksson M, Sundby Hall K, Hartmann JT, Pink D, Schutte J, et al. One vs three years of adjuvant imatinib for operable gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:1265–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demetri GD, van Oosterom AT, Garrett CR, Blackstein ME, Shah MH, Verweij J, et al. Efficacy and safety of sunitinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after failure of imatinib: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368:1329–38. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69446-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demetri GD, Reichardt P, Kang YK, Blay JY, Rutkowski P, Gelderblom H, et al. Efficacy and safety of regorafenib for advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumours after failure of imatinib and sunitinib (GRID): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381:295–302. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61857-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang YK, Ryu MH, Yoo C, Ryoo BY, Kim HJ, Lee JJ, et al. Resumption of imatinib to control metastatic or unresectable gastrointestinal stromal tumours after failure of imatinib and sunitinib (RIGHT): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1175–82. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70453-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ESMO/European Sarcoma Network Working Group Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23 Suppl 7:vii49–55. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang YK, Kang HJ, Kim KM, Sohn T, Choi D, Ryu MH, et al. Clinical practice guideline for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumor in Korea. Cancer Res Treat. 2012;44:85–96. doi: 10.4143/crt.2012.44.2.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le Cesne A, Ray-Coquard I, Bui BN, Adenis A, Rios M, Bertucci F, et al. Discontinuation of imatinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumours after 3 years of treatment: an open-label multicentre randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:942–9. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70222-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demetri GD, Wang Y, Wehrle E, Racine A, Nikolova Z, Blanke CD, et al. Imatinib plasma levels are correlated with clinical benefit in patients with unresectable/metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3141–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.4818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heinrich MC, Corless CL, Blanke CD, Demetri GD, Joensuu H, Roberts PJ, et al. Molecular correlates of imatinib resistance in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4764–74. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Longley BJ, Carter EL. SCF-KIT pathway in human epidermal melanocyte homeostasis. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:139–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park HJ, Kim HS, Kim HJ, Lee JY, Cho BK, Lee AW, et al. Immunohistochemical characterization of cutaneous drug eruptions by STI571. J Dermatol Sci. 2005;38:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fulkerson PC, Rothenberg ME. Targeting eosinophils in allergy, inflammation and beyond. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:117–29. doi: 10.1038/nrd3838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]