Abstract

Introduction

As key experts in supporting medication-decision making, pharmacists are well-positioned to support the incorporation of pharmacogenomics into clinical care. However, there has been little study to date of pharmacists’ information needs regarding pharmacogenomics. Understanding those needs is critical to design information resources that help pharmacists effectively apply pharmacogenomics information.

Objectives

We sought to understand the pharmacogenomics information needs and resource requirements of pharmacists.

Methods

We conducted qualitative inquiries with 14 pharmacists representing 6 clinical environments, and used the results of those inquiries to develop a model of pharmacists’ pharmacogenomics information needs and resource requirements.

Results

The inquiries identified 36 pharmacogenomics-specific and pharmacogenomics-related information needs that fit into four information needs themes: background information, patient information, medication information, and guidance information. The results of the inquiries informed a model of pharmacists’ pharmacogenomics resource requirements, with 3 themes: structure of the resource, perceptions of the resource, and perceptions of the information.

Conclusion

Responses suggest that pharmacists anticipate an imminently growing role for pharmacogenomics in their practice. Participants value information from trust-worthy resources like FDA product labels, but struggle to find relevant information quickly in labels. Specific information needs include clinically relevant guidance about genotypes, phenotypes, and how to care for their patients with known genotypes. Information resources supporting the goal of incorporating complicated genetic information into medication decision-making goals should be well-designed and trustworthy.

Keywords: Pharmacogenomics, genomics, needs assessment, information needs, qualitative inquiry, pharmacists

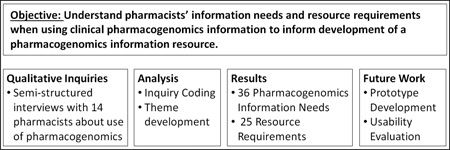

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Pharmacogenomics research has identified over 130 gene variants that can alter the safety and/or effectiveness of drug treatments[1]. Some hospitals have begun using genotype information to inform drug and dose selection for several drugs including warfarin[2,3] and clopidogrel[4,5]. As genotyping becomes more common, pharmacists and physicians will encounter more pharmacogenomic information. To use this information to reduce the risks of adverse events and improve treatment effectiveness, clinicians will need information that will help them interpret complex interactions between patient genotypes, resulting phenotypes, and medications[6,7]. Despite the critical role that pharmacists play in medication decision making, relatively little attention has been paid to date regarding their pharmacogenomics-related information needs and preferences. We present a study of pharmacists’ information needs and resource requirements for pharmacogenomics-based decision making. This work will inform the development of information resources designed to help pharmacists meet the information challenges presented by pharmacogenomics.

1.1 Pharmacists’ Role in Pharmacogenomics Information

As knowledgeable experts who apply their extensive training in drug therapy to provide medication advice, pharmacists play a critical role in providing pharmacogenomics information to prescribing clinicians[8]. Several model pharmacist-led interdisciplinary clinical implementations exist[3,8]. While pharmacists hold positive views of the clinical utility of pharmacogenomics , they do not feel confident in their ability to make recommendations without further education[9,10]. However, little is known about pharmacists’ information needs with respect to pharmacogenomics Although some studies have examined pharmacists’ general drug information needs[11–17] and education requirements regarding pharmacogenomics[18], no studies to date have focused explicitly on pharmacists’ information needs related to pharmacogenomics.

Physicians also lack pharmacogenomics knowledge. They desire information about recommendations, interpretations of genetic test results, testing information, and information about populations most at risk [6], and they value trustworthy, clinically-relevant information about phenotypes and dosage recommendations[7,19,20]. Information resources that address pharmacogenomics information needs can help pharmacists provide the guidance necessary for safe and effective prescribing of drugs with pharmacogenomic implications.

1.2 Pharmacogenomics Information Challenges

Pharmacogenomics involves complex interactions between genes, medication exposure, and patient factors to produce phenotypes[21]. Variations in genes can impact drug response, efficacy, and risk of adverse effects [22]. Each combination presents a unique set of considerations [23,24]. Interpreting this information presents multiple challenges, including potentially confusing descriptions of gene variants, phenotypes, and implications of the interactions. Given a patient with a pharmacogenomic genotype relevant to a medication under consideration, the prescriber must integrate all of this information with patient clinical variables like age and weight to determine the best course of action.

1.3 Pharmacogenomics Information Resources

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires manufacturers to provide relevant pharmacogenomics information in drug product labels of all drugs that have known pharmacogenomic impacts[25]. That information is scattered throughout the label, appearing for different drugs in many different sections. A variety of the widely-used electronic information resources include pharmacogenomic information[26]. However, the information is often incomplete, with resources containing between 50% and 90% of the pharmacogenomics information that is available in FDA approved product labels[26].

As a shared project between the Pharmacogenomics Research Network (PGRN) and the Pharmacogenomics Knowledgebase (PharmGKB), the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC)[27,28] develops guidelines to translate pharmacogenomics knowledge into clinical care[29]. The PharmGKB [30–36] website provides CPIC and Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group (DPWG) guidelines, relevant citations to primary literature, and some product label information[30]. While the research and guideline information are critical, PharmGKB provides only brief excerpts of pharmacogenomics information found in structured product labels, not the exact text of every pharmacogenomics-related statement or the section from which it originated. Consistent with earlier work indicating that pharmacists rely heavily on the information provided by the FDA-mandated labels[37], our informal observations suggest that comprehensive product label information is critical for pharmacists, which raises the concern that they will not trust PharmGKB because they might not perceive that it is communicating authoritative information, despite the FDA statements available on the resource.

1.5 Pharmacogenomics Information Needs and Resource Requirements

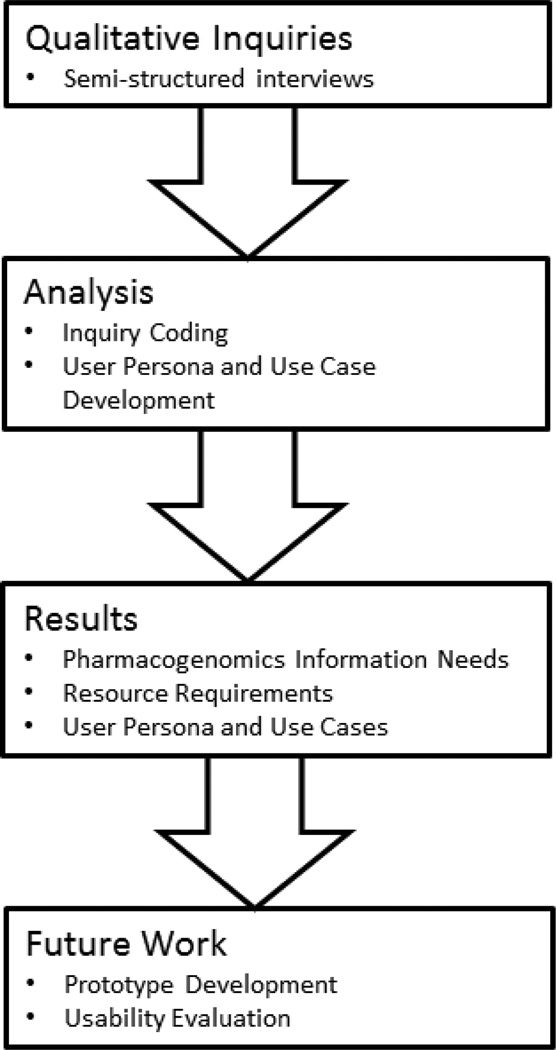

We aim to develop information resources that provide pharmacists with comprehensive, usable, actionable, and trustworthy pharmacogenomic information. We report on a qualitative inquiry of pharmacists’ pharmacogenomics information needs and resource requirements to inform the development of such resources. Figure 1 describes the research project plan.

Figure 1.

Project Workflow

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Qualitative Inquiries

We conducted qualitative inquiries, consisting of semi-structured interviews and observations of pharmacists in their work environment. We coded the interview transcripts and used the results of the interviews to identify pharmacogenomic information needs.

We used a semi-structured approach to elicit a wide range of pharmacist perceptions about information seeking both for general prescribing and specifically with respect to pharmacogenomics. Two authors (KMR and HH) developed an interview guide (supplement) based on information needs research strategies[38,39] .

A trained biomedical informatician with experience and training (KMR) in qualitative research interviewed the participants. Each interview lasted approximately 45 minutes and was audio recorded, with permission from participants. The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board (IRB).

2.2 Participants and setting

We recruited pharmacists through professional connections of the authors using a convenience sampling strategy[39] designed to represent the diversity of needs and perspectives associated with different care contexts including tertiary care centers, community practice, and private nursing home consulting pharmacy. Interviews took place from December 2013-August 2014, and were conducted in the participants’ places of employment. Participants were not compensated in any way for their participation.

2.3 Data analysis

Audio recordings of interviews were transcribed verbatim before being analyzed using descriptive coding[39,40]. We developed a codebook with a preliminary structure answering four basic questions, in general and specific to pharmacogenomics:

What information needs do pharmacists experience while managing drug decisions?

What resources do they use to find drug information and why do they use them?

What do they like and dislike about them?

What tasks do they complete in a typical day related to drug decisions?

We coded using a structural approach, applying conceptual phrases representing ideas related to the research questions to the interview transcripts, and adding subcodes as necessary to more finely represent the participants’ responses[40].. Codes were assigned to sections of text and organized using QSR NVivo™.

Two of the authors (KMR and HH) coded seven of the transcripts independently to identify information need themes related to pharmacogenomics and to revise the emerging codebook accordingly. They discussed the differences to resolve disagreements and achieve consensus on codes used for the remainder of the transcripts. The number of subjects who mentioned each theme was counted for descriptive purposes.

Codes were used to develop a conceptual model of the information needs and information seeking behavior of pharmacists when engaged with pharmacogenomics-related medication information. The conceptual model was presented to two pharmacists to validate the correspondence between the researchers’ and pharmacists’ interpretation of the interview data. The model was revised to correct errors as necessary.

3. Results

3. 1 Participants and setting

Fourteen pharmacists participated. Participants varied in length and type of experience (students, residents, and clinical pharmacists), and distribution of work contexts, including hospital, ambulatory care, nursing homes, and retail pharmacy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant demographics

| Number of pharmacists (n = 14) |

|

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 4 |

| Female | 10 |

| Ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 13 |

| Asian | 1 |

| Years as Pharmacist | |

| <5 | 5 |

| 5–15 | 5 |

| >16 | 4 |

| Years at Current Employer | |

| <5 | 6 |

| 5–15 | 7 |

| >16 | 1 |

| Job Title | |

| Clinical pharmacist - hospital | 5 |

| Clinical pharmacist - nursing home consultant |

3 |

| Clinical pharmacist - ambulatory care |

2 |

| Pharmacy student (3rd year) | 2 |

| Pharmacy resident - hospital | 1 |

| Retail pharmacist | 1 |

| Pharmacogenomics Experience | |

| Had patients with pharmacogenomics testing in last year |

0 |

| Recommended pharmacogenomics testing |

0 |

3.2 Pharmacogenomics in Practice

All of the pharmacists had encountered pharmacogenomics through seminars, continuing education, or reading. None of the participants reported current use of pharmacogenomics information in practice. None had previously recommended genomic testing or managed a patient who had undergone pharmacogenomics testing. However, all anticipated that pharmacogenomics will have a growing impact on their practice in the near future.

3.3 Pharmacogenomics Information Needs

Analysis of the interview transcripts led to the identification of 36 information needs which are either general needs that can apply to pharmacogenomics (Table 2) or needs specific to pharmacogenomics (Table 3). Additional information needs not directly related to pharmacogenomics were also mentioned, but excluded from the final list of 36: general prescribing information such as cost, intravenous stability, and additive information, among others. The full list of information needs is available as supplementary material (Appendix). The information needs were grouped in to four categories: background information, patient-specific information, medication information, and guidance information.

Table 2.

General information needs relevant to pharmacogenomics

| Information Need | No. of Pharmacists (14) |

Example Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Background Information | ||

| Evidence | 6 | “I like…actually being able to pull… the study [where], they actually had data that said that these people did better or didn’t require dosages [changes].”– Pharmacist 9 |

| Patient Information | ||

| Concomitant medications | 9 | [Regarding other information needed]: “Other medications, type of stent, timing (of previous [myocardial infarction]), other medications they might be on, [proton pump inhibitor]PPI controversy, other medical conditions, any other anti-coagulation thrombotic type of conditions the patient might have. That I could find in the e-record. I’m not sure there would be much else outside of that.” – Pharmacist 2 “What other medications he may be receiving, currently…if it was one of those situations where I had to adjust the dose, I would still like to see what else they were on. Because sometimes, depending on some different factors, there could be other anticoagulants involved. You know, even if its low dose aspirin, there could be something potential there that would increase a bleeding risk or a side effect, based on what he was already receiving.” –Pharmacist 10 |

| Medical condition | 7 | |

| Allergies | 3 | |

| Medication previously taken | 1 | |

| Patient preferences | 1 | |

| Length of time taking drug | 1 | |

| Population-specific information |

1 | |

| Medication Information | ||

| Drug Safety | 13 | “If it’s a completely new drug, mechanism of action, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, and depending on the specific question, potentially metabolism, elimination, and major side effects.” – Pharmacist 9 “I would like to know what is the efficacy rate of patients getting clopidogrel with that variant and what are the bleeding rates of patients getting clopidogrel with that variant. I would want, what I always want, is safety and efficacy. Do the risks outweigh the benefits? That’s everything I do so that’s the information I would want.” – Pharmacist 3 “Our system supplies medications in peoples’ claims history, so that they may be filling [drugs] that have the interactions… there’s other ones that I’m not as familiar with and I like to go and actually plug them into a database and see what the interaction is to learn for myself. So I don’t like to arbitrarily say, ‘Oh, there’s an interaction here, like you need to take care of that’ – I like to actually know for myself, like the mechanism of the interaction.”- Pharmacist 5 |

| Drug Efficacy | 12 | |

| Drug-drug interactions | 7 | |

| Other drugs in same class | 4 | |

| Comparative Effectiveness | 3 | |

| Drug toxicity | 3 | |

| Pharmacokinetics | 2 | |

| Drug equivalency | 1 | |

| Mechanism of Action | 1 | |

| Pharmacodynamics | 1 | |

| Drug metabolism | 1 | |

| Drug elimination | 1 | |

| Side effects | 1 | |

| Guidance Information | ||

| Recommendations or guidelines |

14 | “I want to learn more about what is actually going on so that I could understand it and give a clinical recommendation rather than just, “ok, this is what it does and that’s what I should do,” you know? I like reading into it, maybe that would be helpful for some people that really need like a quick answer but I thought it was better to look for what’s actually happening and … this is what’s occurring and this is what you should do.” - Pharmacist 8 |

| Monitoring requirements | 13 | |

| Drug indications | 13 | |

| Dosing | 8 | |

| Alternative drug choices | 6 | |

Table 3.

Pharmacogenomics-specific information needs

| Information Need | No. of Pharmacists (14) |

Example Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Background Information | ||

| Pharmacogenomics Background Information |

10 | “I was definitely looking for just a description of the basic, ‘what does this [gene] do’ before we even talk about the drug” –Pharmacist 8 |

| Pharmacogenomics Evidence | 6 | |

| Test Information | 8 | |

| Test Parameters | 2 | |

| Patient Information | ||

| Phenotype Information | 14 | “What I would want to know is … what does this mean for this person? You know, they’re a poor metabolizer, OK, can I give the drug? Can I not give the drug? If I give the drug, what do I have to do as far as dosing? What do I have to look for, as far as side effects? So, whatever you could do to simplify…you know…poor metabolizer, do this, rapid metabolizer, do this, that would be helpful.” –Pharmacist 10 |

| Variant Information | 13 | |

| Severity of Pharmacogenomics Risk |

4 | |

| Population Frequency (of biomarker) |

3 | |

| Medication Information | ||

| Other drug(s) affected by the biomarker |

5 | “I would want to know if there’s any other drugs that might be affected by this [biomarker]?” –Pharmacist 3 |

| Guidance Information | ||

| Pharmacogenomics Guidelines |

6 | “I would like to see guidelines around it, outcomes research, something that I could confidently say, if we had a drug on formulary we’re thinking about, here’s the patient I would restrict to, here’s the group that needs to be involved to prescribe it.” – Pharmacist 2 |

3.4 Pharmacogenomics Resource Requirements

We categorized perceived strengths and weaknesses of information resources and their contents into three major themes: the structure of the resource, pharmacists’ perception of the resource, and characteristics of the information provided in the resource (Table 4).

Table 4.

Pharmacists requirements for drug information resources

| Requirement | No. of Pharmacists (14) |

Example Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Structure of the Resource | ||

| Has references | 6 | “I liked that it had that reference so that I could click and learn more about it from the original report to the FDA, when they found that. So I liked that. I like to know where things come from. – Pharmacist 13 |

| Visualizations | 6 | |

| Links to other resources | 3 | |

| Peer-reviewed | 1 | |

| Online | 1 | |

| Full-text | 1 | |

| Perception of the Resource | ||

| Organized | 12 | “I like the different sections, and where you can…on the application, hit “Jump to”, and you can quickly go to dosage forms it’s in, or monitoring parameters, and you just jump around very quickly.” – Pharmacist 14 “[It has] pretty thorough information from a reputable source, and it breaks down the various types of information that are available. And depending on the medication, it gives the clinical significance, what has been done, and also the recommendation.” – Pharmacist 9 “We get Micromedex™ for free, so that’s why a lot of people use that one, and I think it’s obviously much more reliable.” – Pharmacist 5 “I couldn’t practice very well without [drug information resources?]. There’s a lot of data that is internal but a lot of this as far as medical education has gone more to focusing on the amount of data that you cannot possibly internalize and the deviations in how quickly it changes, it’s impossible to keep up with every little thing so it’s always good, even if you are sure of something, to check it out.” – Pharmacist 1 |

| Familiar | 8 | |

| Available | 6 | |

| Credible | 5 | |

| Good reputation | 3 | |

| Regularly Updated | 2 | |

| Free | 2 | |

| Helpful | 2 | |

| Reliable | 2 | |

| Necessary | 2 | |

| Good mobile version | 1 | |

| Preferred by physicians | 1 | |

| Perception of the Information | ||

| Easy to use | 14 | “I like it because it’s easy. I usually go to certain ones that I’m familiar enough with, using them online, or in a book, or on my phone, so that I know where to retrieve the information quickly when I need it.” – Pharmacist 10 “Up-To-Date™, you can actually use to treat a patient. Like I have one patient who is going through alcohol withdrawal and you can kind of really look it up and figure out that they need…I think Up-To-Date™ is a lot more useful clinically.” – Pharmacist 14 “I think it’s quick. I think it’s easy. And I think it’s concise. All things that you want, when looking for information of this type. “ – Pharmacist 10 |

| Quick | 13 | |

| Concise | 12 | |

| Thorough | 10 | |

| Clinically relevant | 5 | |

| Accurate | 4 | |

| Objective | 1 | |

Pharmacists expressed strongly felt preferences for drug information resources. All participants discussed using multiple resources as needed for particular situations, including tertiary resources (e.g. Lexicomp™, Up-To-Date™, and Micromedex™), primary literature, the FDA, and drug companies’ literature. Eleven out of 14 pharmacists mentioned using the FDA product labels. Although participants described FDA product labels as being trustworthy, these labels were not usually the preferred first choice. Many stated that they dislike seeking information in the product label because “the hard part about the label is you end up having to go to multiple sections to find information.” (Pharmacist 2). One pharmacist described starting with a tertiary resource and then proceeding to the labels and final to primary literature for confirmation: “I like to confirm everything a couple places and sometimes the labels are a little behind the actual evidence. So I would probably take this information, go to the literature to see if I could confirm that.” This was also mentioned by another respondent who described confirming using the product label to confirm details because “not that there’s bias, or potentially wrong information, but getting it from the source is better than…more accurate, generally, is what I would say.”

Discussion

We identified perceived identified information needs, both general and specific to pharmacogenomics, relevant to pharmacists’ use of pharmacogenomics information. These needs encompass both the information needed and the requirements for compendia and other resources containing these details. To our knowledge, this is the first study to explicitly identify pharmacogenomics-related information needs of pharmacists, and to discuss these needs in the context of preferences and requirements regarding pharmacy information resources.

4.1 Pharmacogenomics Information Needs

Participating pharmacists’ information needs, both generally and specifically for pharmacogenomics, fall into four categories: background, medication, patient-specific, and guidance-related information. These needs are similar to those of physicians, particularly with respect to the interpretation of test results, recommendations for alternatives, prevalence in various ethnic groups, and genotypic testing information[6,7]. We found specific information needs directly and indirectly related to pharmacogenomics that similar studies of physicians’ pharmacogenomics knowledge gaps[6] and of the usability of pharmacogenomics decision support aids [7] did not identify. These include monitoring information, severity of risk, and other drugs affected by a biomarker.

The perceptions of the pharmacists are likely influenced by the environment in which they practice. For instance, while none of the pharmacists have encountered patients with pharmacogenomic testing, some were more familiar with the concept than others. Nursing home consultant pharmacists had very little exposure to pharmacogenomics, while the hospital based resident pharmacists had enough familiarity to know recommendations for treating CYP2C19 poor metabolizers.

4.2 Pharmacogenomics Information Resource Requirements

Pharmacists in this study prefer resources that are peer-reviewed, online, full-text, referenced, with visualizations and links to other sources (Structure of the Resource). They perceive high quality resources to be familiar, trustworthy, up-to-date, and well organized (Perceptions of the Resource). Finally, they perceive high quality information to be quick, concise but thorough, relevant, accurate, and easy to use (Perceptions of the Information). In particular, they are very concerned with the provenance of the information: they want references, access to full-text studies, and prefer information that comes from FDA-mandated product labels. If they are unsure of the provenance, they prefer to rely solely on the contents of the product label.

The participation of pharmacists working in a range of contexts of care supports the generalizability of our results. Participants included pharmacists working in hospitals, nursing homes, ambulatory care, retail pharmacies, along with pharmacy students and a resident. Although these participants were not chosen to be representative of a broader sample, similarities in the responses suggest that the concerns and information needs regarding pharmacogenomics may be similar across these work environments. However, resource requirements are likely influenced by practice environments. The pharmacists who do not have access to high speed Internet, such as those who are dependent on wireless, found the slow speed of some resources to be an impediment not experienced by hospital-based pharmacists with powerful networks. Differing work contexts also clearly influenced the selection and use of existing resources, with pharmacists frequently stating that they depended on the resources paid for and promoted by their employers. Pharmacists who practiced in the out-patient clinic specifically spoke favorably of their preferred resource, which they described as depicting information in ways not replicated by other resources.

4.3 Pharmacogenomics in Qualitative Research

While multiple studies have examined the pharmacogenomics education needs of pharmacists[9,10,41,42], none have explicitly addressed their information needs for clinical decision making to better meet those needs. This study complements the findings of other recent qualitative studies focused on pharmacogenomics information needs of physicians, not pharmacists. A study published by Devine et al. in 2014 looked at the usability of a computerized decision support alert that presented pharmacogenomics information[7]. They also showed the prototype to cardiologists and oncologists for usability feedback. However, they did not conduct qualitative inquiries to explicitly identify information needs and resource requirements. Their analysis identified some major information needs, such as the need for clinically relevant information about phenotypes and variants, without identifying what makes the information clinically relevant. Our interviews provided in-depth feedback not available in the usability assessment conducted by Devine, et al., identifying specific factors that make information clinically relevant, including patient demographics, concomitant medications, and comorbid conditions.

A 2014 paper from by Johansen Taber, et al. assessed physicians’ knowledge level regarding pharmacogenomics, rather than focusing on information necessary for making clinical decisions[6]. Our results are consistent with their findings: clinicians in general have not encountered pharmacogenomics much in practice, and they have gaps in knowledge. They also asked physicians what information they would like in a pharmacogenomics resource, identifying items also found in our study, including information on test results, recommendations, mechanism of action, demographics, references, testing information, and drug labeling information. Differences in information need themes are listed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Pharmacogenomics Themes

These differences in information needs may be a result of differences in the types of study (usability evaluation and knowledge assessment, compared to our information needs study), or the difference in study population (physicians versus pharmacists). Clinicians of all types experience pharmacogenomics information needs, and resources meeting those needs will have to support many types of users and queries.

4.5 Limitations

Researcher bias in analysis and interpretation can be a limitation of studies of this type. To address this bias, the transcripts were reviewed and coded with 50% overlap by two researchers. Discrepancies in agreement were discussed by the coders and brought to consensus. In addition, we validated the results with member checks with pharmacists.. While the study provides a detailed description of pharmacists’ information seeking behavior and information needs, the results may not be generalizable to all pharmacists or all clinicians in other settings.

4.6 Future Work

We are currently integrating the results of this study into the design and implementation of a clinically-oriented pharmacogenomics information resource that contains pharmacogenomics statements annotated from structured product labels. A laboratory-based task analysis[38,43] will assess the utility of the tool in helping pharmacists locate and use information to make clinical decisions.

Conclusions

As medication experts with a key role in medication decision-making, pharmacists are poised to lead the incorporation of pharmacogenomics information into clinical care. For a small set of drugs, the benefits of pharmacogenomics are clear[4,5,25,44–55] and the pace of research in this field has been rapid[56]. Genotyping will ideally enable clinicians to give their patients the most effective drug while reducing the risk of adverse events. Simply knowing the patient’s genotype is insufficient for treatment decisions; knowing how to proceed based on the genotype is critical. Our work identifies pharmacogenomics information needs of pharmacists and requirements for meeting those needs. High priority for future work includes the design of a pharmacogenomics information resource to address information gaps as genotyping becomes more standard practice. A resource that gathers pharmacogenomics information from trustworthy resources and presents it in a way that is usable and actionable supports the practical application of pharmacogenomics to clinical care.

Highlights.

We used qualitative inquiries to elicit pharmacogenomics information needs and resource requirements of pharmacists.

Managing medications for patients with genotypes that impact those medications requires incorporating complex information about genotypes, phenotypes, severity, concomitant medications, guidelines, and evidence to make an informed decision.

Pharmacists value concise but thorough information from sources they trust.

Pharmacists seek information about the implication of the variant, other drugs affected by the variant, and recommendations for treating that patient.

Summary Points.

Clinicians of various types are going to encounter pharmacogenomics in clinical practice, and pharmacists are already positioned to support the use of pharmacogenomics in decision making.

Pharmacists need concise, trustworthy pharmacogenomics information that supports multiple aspects of clinical decision making.

Knowing the patient’s genotype is insufficient; knowing how to proceed is critical.

When designing a pharmacogenomics information resource or clinical decision support tool, pharmacists’ information needs and resource requirements should be considered.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank staff from UPMC, the University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy, and RxPartners for participating in this study; Dr. Michael Becich for his support and guidance in the development of this project; Jane Dirks and Nova Smith for their assistance with transcription; and Dr. Matthias Samwald for his feedback on this manuscript. This work was funded in part by the NLM Training Grant 5 T15 LM007059, National Institute on Aging grant K01AG044433, National Library of Medicine grant R01LM011838, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grant KL2 TR000146.

Appendix

| Name | Sources | References |

|---|---|---|

| Information need | 11 | 351 |

| Background Information | 3 | 3 |

| Insurance information | 2 | 3 |

| Location of information | 1 | 2 |

| medical condition | 5 | 9 |

| Allergies | 2 | 2 |

| Bleeding risk | 1 | 1 |

| Patient’s weight | 1 | 1 |

| medication information | 11 | 330 |

| Additive information | 1 | 1 |

| Comparative effectiveness | 3 | 6 |

| Concomitant medications | 6 | 7 |

| Dispensing information | 1 | 1 |

| dosing | 6 | 14 |

| Drug availability | 1 | 2 |

| Drug compatibility | 2 | 2 |

| Drug efficacy | 10 | 17 |

| Drug equivalency | 1 | 2 |

| Drug identification | 1 | 1 |

| Drug indications | 11 | 18 |

| Drug Safety | 11 | 42 |

| Adverse effects | 8 | 23 |

| Drug-drug interactions | 5 | 12 |

| Frequency of interaction | 1 | 1 |

| Severity of interaction | 2 | 2 |

| Side effects | 1 | 3 |

| Drug toxicity | 3 | 6 |

| Evidence | 2 | 2 |

| Guidelines about the drug | 11 | 11 |

| IV information | 5 | 7 |

| IV compatibility | 2 | 2 |

| IV extravasation instructions | 1 | 1 |

| IV stability | 1 | 2 |

| Length of time taking medication | 1 | 1 |

| Mechanism of action | 1 | 1 |

| medication appropriateness | 1 | 1 |

| Monitoring requirements | 11 | 14 |

| Novel drug | 1 | 1 |

| Off-label use | 1 | 1 |

| Other drugs in same class | 3 | 3 |

| Patient population-specific information | 1 | 1 |

| Pharmacodynamics | 1 | 1 |

| Name | Sources | References |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmacogenomics information | 11 | 135 |

| Other drug(s) affected by biomarker | 4 | 4 |

| Pharmacogenomics background information | 8 | 11 |

| Pharmacogenomics evidence | 4 | 9 |

| Pharmacogenomics guidelines | 4 | 12 |

| Phenotype information | 11 | 30 |

| Severity of pharmacogenomics risk | 2 | 2 |

| test information | 6 | 11 |

| Test parameters | 2 | 3 |

| variant information | 10 | 37 |

| Population frequency | 1 | 2 |

| Pharmacokinetics | 1 | 2 |

| Drug elimination | 1 | 1 |

| Drug Metabolism | 0 | 0 |

| Price | 2 | 3 |

| protocol information | 0 | 0 |

| QTc interval | 2 | 2 |

| recommendation | 11 | 28 |

| Alternative drug choices | 5 | 5 |

| Patient preferences | 1 | 1 |

| Pharmacogenomics information | 11 | 135 |

| Other drug(s) affected by biomarker | 4 | 4 |

| Pharmacogenomics background information | 8 | 11 |

| Pharmacogenomics evidence | 4 | 9 |

| Pharmacogenomics guidelines | 4 | 12 |

| Phenotype information | 11 | 30 |

| Severity of pharmacogenomics risk | 2 | 2 |

| test information | 6 | 11 |

| Test parameters | 2 | 3 |

| variant information | 10 | 37 |

| Population frequency | 1 | 2 |

| Pharmacokinetics | 1 | 2 |

| Drug elimination | 1 | 1 |

| Drug Metabolism | 0 | 0 |

| Price | 2 | 3 |

| protocol information | 0 | 0 |

| QTc interval | 2 | 2 |

| recommendation | 11 | 28 |

| Alternative drug choices | 5 | 5 |

| Patient preferences | 1 | 1 |

| Pharmacogenomics information | 11 | 135 |

| Other drug(s) affected by biomarker | 4 | 4 |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

Katrina Romagnoli designed and executed the project, performed data collection and analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

Richard Boyce provided significant help in designing the project, participant recruitment, and preparing the manuscript.

Philip Empey provided significant help in designing the project, participant recruitment, and preparing the manuscript.

Solomon Adams provided help in preparing the interviews and the manuscript.

Harry Hochheiser provided significant help in the design and execution of the project, data analysis, and preparing the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Declaration

We wish to confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

We confirm that the manuscript has been read and approved by all named authors and that there are no other persons who satisfied the criteria for authorship but are not listed. We further confirm that the order of authors listed in the manuscript has been approved by all of us.

We confirm that we have given due consideration to the protection of intellectual property associated with this work and that there are no impediments to publication, including the timing of publication, with respect to intellectual property. In so doing we confirm that we have followed the regulations of our institutions concerning intellectual property.

We further confirm that any aspect of the work covered in this manuscript that has involved human subjects has been conducted with the ethical approval of all relevant bodies and that such approvals are acknowledged within the manuscript.

We understand that the Corresponding Author is the sole contact for the Editorial process (including Editorial Manager and direct communications with the office). She is responsible for communicating with the other authors about progress, submissions of revisions and final approval of proofs. We confirm that we have provided a current, correct email address which is accessible by the Corresponding Author.

Signed by all authors as follows:

Katrina M. Romagnoli

![]()

Richard Boyce

![]()

Harry Hochheiser

Philip Empey

Solomon Adams

References

- 1.Frueh FW, Amur S, Mummaneni P, Epstein RS, Aubert RE, DeLuca TM, et al. Pharmacogenomic biomarker information in drug labels approved by the United States food and drug administration: prevalence of related drug use. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28:992–998. doi: 10.1592/phco.28.8.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kangelaris KN, Bent S, Nussbaum RL, Garcia DA, Tice JA. Genetic testing before anticoagulation? A systematic review of pharmacogenetic dosing of warfarin. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:656–664. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0949-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nutescu EA, Drozda K, Bress AP, Galanter WL, Stevenson J, Stamos TD, et al. Feasibility of implementing a comprehensive warfarin pharmacogenetics service. Pharmacotherapy. 2013;33:1156–1164. doi: 10.1002/phar.1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pulley JM, Denny JC, Peterson JF, Bernard GR, Vnencak-Jones CL, Ramirez AH, et al. Operational implementation of prospective genotyping for personalized medicine: the design of the Vanderbilt PREDICT project. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;92:87–95. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson JA, Elsey AR, Clare-Salzler MJ, Nessl D, Conlon M, Nelson DR. Institutional profile: University of Florida and Shands Hospital Personalized Medicine Program: clinical implementation of pharmacogenetics. Pharmacogenomics. 2013;14:723–726. doi: 10.2217/pgs.13.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johansen Taber KA, Dickinson BD. Pharmacogenomic knowledge gaps and educational resource needs among physicians in selected specialties. Pharmgenomics Pers Med. 2014;7:145–162. doi: 10.2147/PGPM.S63715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devine EB, Lee C-J, Overby CL, Abernethy N, McCune J, Smith JW, et al. Usability evaluation of pharmacogenomics clinical decision support aids and clinical knowledge resources in a computerized provider order entry system: a mixed methods approach. Int J Med Inform. 2014;83:473–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Owusu-Obeng A, Weitzel KW, Hatton RC, Staley BJ, Ashton J, Cooper-Dehoff RM, et al. Emerging roles for pharmacists in clinical implementation of pharmacogenomics. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:1102–1112. doi: 10.1002/phar.1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuteja S, Haynes K, Zayac C, Sprague JE, Bernhardt B, Pyeritz R. Community pharmacists’ attitudes towards clinical utility and ethical implications of pharmacogenetic testing. Per Med. 2013;10:793–800. doi: 10.2217/pme.13.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Denus S, Letarte N, Hurlimann T, Lambert J-P, Lavoie A, Robb L, et al. An evaluation of pharmacists’ expectations towards pharmacogenomics. Pharmacogenomics. 2013;14:165–175. doi: 10.2217/pgs.12.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan TYK, Lee KKC, Critchley JAJH. The needs and sources of drug information among pharmacists in Hong Kong. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1996;21:325–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.1996.tb00026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zehnder S, Beutler M, Bruppacher R, Ehrenhöfer T, Hersberger KE. Needs and use of drug information sources in community pharmacies: a questionnaire based survey in German-speaking Switzerland. Pharm World Sci. 2004;26:197–202. doi: 10.1023/b:phar.0000035881.17853.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong P-SJ, Ko Y, Sklar GE. Identification and evaluation of pharmacists’ commonly used drug information sources. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:347–352. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lua H-L, Sklar G, Ko Y. Identification and physicians’ views of their commonly-used drug information sources in Singapore. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33:772–778. doi: 10.1007/s11096-011-9533-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kostagiolas PA, Bairaktaris KD, Niakas D. An information behaviour investigation of the community pharmacists in Greece for developing library and information services. Health Info Libr J. 2010;27:46–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kostagiolas PA, Aggelopoulou VA, Niakas D. A study of the information seeking behaviour of hospital pharmacists: empirical evidence from Greece. Health Info Libr J. 2011;28:302–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2011.00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burke W. Genetic Test Evaluation: Information Needs of Clinicians, Policy Makers, and the Public. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:311–318. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCullough KB, Formea CM, Berg KD, Burzynski JA, Cunningham JL, Ou NN, et al. Assessment of the pharmacogenomics educational needs of pharmacists. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75:51. doi: 10.5688/ajpe75351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zachariah M, Phansalkar S, Seidling HM, Neri PM, Cresswell KM, Duke J, et al. Development and preliminary evidence for the validity of an instrument assessing implementation of human-factors principles in medication-related decision-support systems--I-MeDeSA. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(Suppl 1):i62–i72. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neri PM, Pollard SE, Volk LA, Newmark LP, Varugheese M, Baxter S, et al. Usability of a novel clinician interface for genetic results. J Biomed Inform. 2012;45:950–957. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rutherford SL. From genotype to phenotype: buffering mechanisms and the storage of genetic information. Bioessays. 2000;22:1095–1105. doi: 10.1002/1521-1878(200012)22:12<1095::AID-BIES7>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.FDA. [accessed March 31, 2015];Genomics - Table of Pharmacogenomic Biomarkers in Drug Labels. n.d. http://www.fda.gov/drugs/scienceresearch/researchareas/pharmacogenetics/ucm083378.htm.

- 23.Ma JD, Lee KC, Kuo GM. Clinical application of pharmacogenomics. J Pharm Pract. 2012;25:417–427. doi: 10.1177/0897190012448309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amstutz U, Carleton BC. Pharmacogenetic testing: time for clinical practice guidelines. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:924–927. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.FDA. Guidance for Industry: Clinical Pharmacogenomics: Premarketing Evaluation in Early Phase Clinical Studies. 2011 http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm337169.pdf.

- 26.Vaughan KTL, Scolaro KL, Anksorus HN, Roederer MW. An evaluation of pharmacogenomic information provided by five common drug information resources. J Med Libr Assoc. 2014;102:47–51. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.102.1.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Relling MV, Klein TE. CPIC: Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium of the Pharmacogenomics Research Network. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:464–467. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caudle KE, Klein TE, Hoffman JM, Muller DJ, Whirl-Carrillo M, Gong L, et al. Incorporation of pharmacogenomics into routine clinical practice: the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline development process. Curr Drug Metab. 2014;15:209–217. doi: 10.2174/1389200215666140130124910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shuldiner AR, Relling MV, Peterson JF, Hicks JK, Freimuth RR, Sadee W, et al. The Pharmacogenomics Research Network Translational Pharmacogenetics Program: overcoming challenges of real-world implementation. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;94:207–210. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2013.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.F Thorn C, E Klein T, B Altman R. Pharmacogenomics and bioinformatics: PharmGKB. Pharmacogenomics. 2010;11:501–505. doi: 10.2217/pgs.10.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gong L, Owen RP, Gor W, Altman RB, Klein TE. PharmGKB: an integrated resource of pharmacogenomic data and knowledge. Chapter 14:Unit14.7. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2008 doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1407s23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Altman RB. PharmGKB: a logical home for knowledge relating genotype to drug response phenotype. Nat Genet. 2007;39:426. doi: 10.1038/ng0407-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hewett M, Oliver DE, Rubin DL, Easton KL, Stuart JM, Altman RB, et al. PharmGKB: the Pharmacogenetics Knowledge Base. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:163–165. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sangkuhl K, Berlin DS, Altman RB, Klein TE. PharmGKB: understanding the effects of individual genetic variants. Drug Metab Rev. 2008;40:539–551. doi: 10.1080/03602530802413338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klein TE, Chang JT, Cho MK, Easton KL, Fergerson R, Hewett M, et al. Integrating genotype and phenotype information: an overview of the PharmGKB project. Pharmacogenetics Research Network and Knowledge Base. Pharmacogenomics J. 2001;1:167–170. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hernandez-Boussard T, Whirl-Carrillo M, Hebert JM, Gong L, Owen R, Gong M, et al. The pharmacogenetics and pharmacogenomics knowledge base: accentuating the knowledge. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D913–D918. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boyce RD, Freimuth RR, Romagnoli KM, Pummer T, Hochheiser H, Empey PE. Toward semantic modeling of pharmacogenomic knowledge for clinical and translational decision support. AMIA Summits Transl Sci Proc. 2013:28–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friedman CP. Evaluation Methods in Biomedical Informatics. 2nd. New York: Springer Science & Business Media; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. vol. 3rd. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saldaña J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Owen RP, Klein TE, Altman RB. The education potential of the pharmacogenetics and pharmacogenomics knowledge base (PharmGKB) Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;82:472–475. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee KC, Ma JD, Kuo GM. Pharmacogenomics: bridging the gap between science and practice. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;50:e1–e14. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2010.09124. n.d.; quiz e15–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boland MR, Rusanov A, So Y, Lopez-Jimenez C, Busacca L, Steinman RC, et al. From expert-derived user needs to user-perceived ease of use and usefulness: a two-phase mixed-methods evaluation framework. J Biomed Inform. 2014;52:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.George J, Doney A, Palmer CN, Lang CC. Pharmacogenetics testing: implications for cardiovascular therapeutics with clopidogrel and warfarin. Cardiovasc Ther. 2010;28:135–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5922.2010.00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klein TE, Altman RB, Eriksson N, Gage BF, Kimmel SE, Lee M-TM, et al. Estimation of the warfarin dose with clinical and pharmacogenetic data. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:753–764. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schildcrout JS, Denny JC, Bowton E, Gregg W, Pulley JM, Basford MA, et al. Optimizing drug outcomes through pharmacogenetics: a case for preemptive genotyping. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;92:235–242. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De Graaff LCG, van Schaik RHN, van Gelder T. A clinical approach to pharmacogenetics. Neth J Med. 2013;71:145–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilkinson GR. Drug metabolism and variability among patients in drug response. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2211–2221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dancey JE, Bedard PL, Onetto N, Hudson TJ. The genetic basis for cancer treatment decisions. Cell. 2012;148:409–420. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Epstein RS, Moyer TP, Aubert RE, O Kane DJ, Xia F, Verbrugge RR, et al. Warfarin genotyping reduces hospitalization rates results from the MM-WES (Medco-Mayo Warfarin Effectiveness study) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2804–2812. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mallal S, Phillips E, Carosi G, Molina J-M, Workman C, Tomazic J, et al. HLA-B*5701 screening for hypersensitivity to abacavir. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:568–579. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De Leon J, Sandson NB, Cozza KL. A preliminary attempt to personalize risperidone dosing using drug-drug interactions and genetics: part I. Psychosomatics. 49:258–270. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.49.3.258. n.d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mega JL, Simon T, Collet J-P, Anderson JL, Antman EM, Bliden K, et al. Reduced-function CYP2C19 genotype and risk of adverse clinical outcomes among patients treated with clopidogrel predominantly for PCI: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;304:1821–1830. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhou S-F. Polymorphism of human cytochrome P450 2D6 and its clinical significance: Part I. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2009;48:689–723. doi: 10.2165/11318030-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.El-Ibiary SY, Cheng C, Alldredge B. Potential roles for pharmacists in pharmacogenetics. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;48:e21–e29. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2008.07050. n.d.; quiz e30–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kimmel SE, French B, Kasner SE, Johnson JA, Anderson JL, Gage BF, et al. A pharmacogenetic versus a clinical algorithm for warfarin dosing. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2283–2293. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]