Abstract

Background:

Few studies have estimated care burden in large, representative, multi-ethnic Asian population-based informal caregivers of older adults with care needs. This study describes informal caregivers’ care participation for a population-based sample of older adults with care needs in Singapore, investigates differences by dementia status, and examines correlates of caregivers’ burden.

Methods:

Data collected from 693 pairs of older adults, aged 60 to 100 years, having any care needs, and their informal caregivers, who were aged 21 to 88 years, closely involved in their care and “knew the older resident best,” and were interviewed during a cross-sectional national survey, were used. Clinical characteristics of older adults, including behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) and dementia diagnosis, care needs, and socio-demographic characteristics of participants were obtained. Care burden was assessed with the Zarit Burden Interview.

Results:

Informal caregivers’ participation was highest in activities related to communication (35.1%), feeding (32%), and bathing (21.1%). Among the older adults with any care need, 356 (51.4%) had dementia. Care burden was significantly associated with married caregivers (odds ratio (OR) 2.4 vs. never married), when their relative belonged to a younger cohort (OR 2.5 vs. >84 years), needed care much of the time (OR 2.5 vs. no care needed), exhibited BPSD (OR 3.5 vs. no BPSD), and had dementia (OR 2.52 vs. no dementia).

Conclusions:

Factors related to older adults – more care needs, presence of BPSD, and dementia – were significant contributors to informal caregivers’ burden, and these should be considered while planning interventions to alleviate care burden.

Key words: behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, care need, correlates of care burden, Zarit Burden Interview

Introduction

Older populations typically have multiple medical problems, huge healthcare utilization, require multiple service approaches, and need caregivers to take care of their health and care requirements (Bähler et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2015), all of which impose significant challenges in their management. With the focus on rehabilitation and managing care in the right setting, such as the community, the role and process of caring for older adults often emerges naturally among families. While benefits of active informal caregiving result in better patient management and lower resource utilization for the healthcare systems, the personal cost to the family caregiver can be substantial. As a result, informal caregivers of older adults often experience significant long-term burden of care (Prince et al., 2012; Ikeda et al., 2015). Informal caregivers’ role varies by the care need of older adults, which often precedes a formal diagnosis of common geriatric illnesses such as stroke or dementia (Prince et al., 2004), and these influence the care burden experienced by caregivers. However, extant findings on the relationship of caregivers’ socio-demographic characteristics, such as age, gender, and the relationship with the older adult, on care burden are inconclusive (Dunkin and Anderson-Hanley, 1998; Gallicchio et al., 2002; Chumbler et al., 2003).

Singapore is a developed sovereign city-state in Southeast Asia, situated off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula. In 2013, the country's resident population (Singapore Citizens and Permanent Residents) stood at 3.8 million, comprising Chinese (74.2%), Malay (13.2%), Indian (9.2%), and other ethnicities (3.3%) (http://www.singstat.gov.sg). With advances in healthcare and population well-being, the life expectancy rate among those aged 65 years and above has increased from about 17 years in 2000 to 20.2 years in 2013 (http://www.singstat.gov.sg). However, with the faltering family size and fertility rate, the old-age support ratio of residents has continued to fall from 13.5 in 1970 to 8.4 in 2000 to 6.4 in 2013. While the older adult population is expected to triple to 900,000 by 2030, there will only be 2.1 working-age citizens for each citizen aged 65 years and above (http://app.msf.gov.sg/portals/0/summary/research/Materials_IMCReport.pdf). This presents several challenges in terms of care and support, and highlights the critical role of informal caregivers in elder care in Singapore.

Although caregivers’ burden and its predictors have been extensively studied among clinical and help-seeking older populations (Etters et al., 2008), there has been insufficient research on nationally representative samples in developed nations and particularly in multi-ethnic Asian populations. Thus, there is still a need to identify the major factors contributing to caregivers’ burden in Asian samples based on large-scale representative data using appropriate methodology among general caregiver populations. Previous studies among Singapore's older population have reported a correlation between dementia and caregivers’ burden (Mehta, 2005; Tan et al., 2005; Tew et al., 2010). However, these studies were limited in terms of the sample size and focused on specific population groups. Moreover, with the recent changes in caregiver demographics, healthcare policies, and resulting impact on care arrangements for older residents, it is of interest to establish the socio-demographic profiles of their informal care providers and investigate the presence and correlates of care burden among family caregivers in a large population sample.

Data for this study were collected during the Well-being of the Singapore Elderly (WiSE) study, which was a large, population-based, cross-sectional survey conducted to estimate the prevalence and factors associated with dementia in Singapore. The present study aimed to (1) describe the care participation, care needs, and care burden among informal caregivers of a cohort of older adults with care needs in Singapore, (2) investigate the association of dementia with these, and (3) examine factors related to the care burden experienced by their informal caregivers.

Methods

The WiSE survey was conducted across Singapore with older adults aged 60 years and above and their respective family member or a close friend – referred to as “informant.” Ethical approval to conduct the study was obtained from the relevant ethics committees. Study details have been explained elsewhere (Subramaniam et al., 2015).

Briefly, older adults aged 60 years and above were randomly selected from a national database with information on all residents in Singapore. Those who were younger than 60 years, without any address or with overseas addresses as of June 2011, and all foreigners were excluded from the frame. A probability sample was randomly selected using a disproportionate stratified sampling design with 12 strata defined according to ethnicity (Chinese (38.5%), Malay (30%), Indian (30%), others (1.5%)) and age groups (60 to 74, 75 to 84, and 85 years and above). Residents aged 75 years and above, Malays, and Indians were over-sampled to ensure that sufficient sample size would be achieved to improve the reliability of estimates for the subgroup analyses and to account for cultural differences in the three main ethnic groups in Singapore. This study involved a single-stage design without geographic clustering. A total of 2,565 older adults were interviewed between August 2012 and November 2013, giving a response rate of 66%.

Informed consent was obtained from participants themselves or through their legally acceptable representatives (for those participants who were mentally or physically incapable to consent themselves). Each older participant was then asked to identify one family member or friend, who according to the older participant was most involved in their care and “who knew the older adult best,” and therefore best suited to participate in the survey. Informants were eligible for the survey if they were Singapore residents, aged 21 years and above, and were able to provide adequate and accurate information on the older person's health condition and service use. While some informants were caregivers (i.e. actively involved in care provision of the older person), others were co-residents or other close contacts with no caregiving role. Approximate time spent with the older person was used as a criterion for deciding the best informant in the situation where there were several co-resident family members involved in the care or decision-making of the older person. Informants were excluded from the sample if (a) interviewers were unable to contact them after ten contact attempts, (b) they were non-residents of Singapore, residing outside Singapore at the time of the survey, (c) they were unwilling or unable to complete the interview in any of the four languages – English, Chinese (either Mandarin or one of three dialects – Hokkien, Teochew, or Cantonese), Malay, or Tamil, or (d) they were paid caregivers.

A total of 2,421 informants were interviewed during the survey; 117 of the 2,565 older adults did not have any relative or friend who could be interviewed, or refused to refer another family member for the survey, or potential informal caregivers were ineligible based on resident status, age, language, or mental/physical capacity. Among the remaining, 22 refused to participate in the survey and five could not be contacted or interviewed after repeated attempts, resulting in an overall loss of information in about 5% of the sample of informants. For this paper, data from 693 (28.6% of the full survey sample) pairs of older adults who needed any care and their informants, who were also their informal caregivers, were used. “Informants” of this group of older adults are referred to as “informal caregivers,” henceforth.

The 10/66 Study Protocol was adapted for this study (Prince et al., 2007). Details are provided in another article (Subramaniam et al., 2015). A 10/66 dementia diagnosis was obtained with the Geriatric Mental State (GMS) using a computerized algorithm (AGECAT) along with other measures such as the Community Screening Interview for Dementia (CSI-D), Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD) test battery, History and Aetiology Schedule – Dementia Diagnosis and Subtype (HAS-DDS), and neurological assessments (Prince et al., 2007). The 10/66 dementia diagnosis, established to define a “broader category of dementia that may be more sensitive, identifying genuine cases beyond those defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) algorithm, with relevance to the estimation of the population burden of this disorder,” has been validated against the DSM-IV diagnoses (Prince et al., 2008; Phung et al., 2014; Subramaniam et al., 2015).

The following information was collected from the informal caregivers.

Socio-demographic information: Information on older adults’ age and gender and caregivers’ age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, education, relationship to the older adult, whether they lived with the older person, etc. were collected.

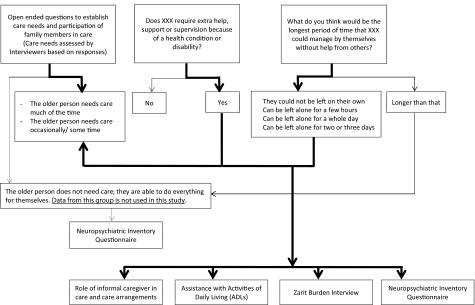

Care need, care arrangement, and care participation of informal caregivers: Data on informants’ involvement in the care of an older adult were collected as shown in Figure 1. They were asked to report if the older adult “required extra help, support, or supervision because of a health condition or disability” and what was the “longest period of time (a few hours/whole day/two to three days/longer than that) they could manage by themselves, without help from others, supposing they were living on their own.” Interviewers also collected information on care arrangements using supplemental open-ended questions from all informants (who lives with X?, what kind of help is needed by X inside and outside the house?, who provides this help?, etc.). Informants who reported “No” to the first question and “longer than that” to the second, did not answer questions related to the care needs. Based on this, and responses to the open-ended questions, the interviewers then assessed whether the older adult needed care “much of the time, some of the time, or did not need care” (i.e. they were able to do everything for themselves). Informants of older persons who “did not need care” were not asked further questions related to their care needs and their data were excluded from this study. Informal caregivers of older adults with some/much care needs were then asked questions on their involvement in care for the older person using a list of eight activities of daily living (ADLs) – communicating with the person, supervising the person, and helping them with using transport, dressing, eating, grooming (looking after their appearance), toileting, and bathing. These activities were presented to the caregivers, and they were asked to report “how much time they spent doing each of these in the past 24 h.” Information on their participation in each was captured using four options – no time, less than 1 h, 1 to 2 h, more than 2 h. Information on care arrangements, such as whether the caregiver was the “main hands-on” or “organizational” caregiver, whether they had given up or cut down on their work to care for the older person and the involvement of other family members/friends/paid-helpers, etc were also captured.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of data collection from informal caregivers on care needs of older adults.

Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) and care burden: The Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q) was used to assess the presence of BPSD during last month by the older adult on the following 12 categories: delusions, hallucinations, anxiety, depression/dysphoria, agitation/aggression, elation/euphoria, disinhibition, irritability/lability, apathy/indifference, motor disturbance, night-time behavior problems, and problems with appetite/eating (Kaufer et al., 2000). Informal caregivers were asked whether the older person exhibited each of these behaviors (e.g. “Does X believe that others are stealing from him or her, or planning to harm him or her in some way?,” “Does X act as if he/she is sad or in low spirits?”).

Informal caregivers were also administered the Zarit Burden Inventory (ZBI; Zarit et al., 1980), which is a widely used 22-item self-report inventory that measures subjective care burden among caregivers. Its validity has been established in Singapore (Seng et al., 2010). The scale items examined burden associated with functional/behavioral impairments and the home care situations. Each item was scored on a 5-point Likert Scale ranging from “never” to “nearly always present.” A total score was obtained, with higher scores indicting higher care burden among informal caregivers. The ZBI scores were dichotomized using a cut-off of 24 (Schreiner et al., 2006) to identify correlates of care burden in this group.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics for socio-demographic variables and measures applied to caregivers were computed using the SPSS version 18.0. χ2-tests and Mann–Whitney U tests were used for comparisons of categorical and continuous variables respectively among informal caregivers of those with and without dementia. To identify factors related to care burden, multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed with the presence of burden being the dependent variable, and older adults’ age, gender, care need, presence of BPSD, and dementia status, and caregivers’ age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, education level, having children, relationship with the older adult, whether they lived with the older person, and, received paid or unpaid help with care, as independent variables. Two-sided tests were applied and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Socio-demographic profile of informal caregivers of older adults with care need

The mean age of the informal caregivers was 54.5 (SD 12.9) years, ranging from 21 to 88 years. The majority of the caregivers were aged between 50 and 64 years (45.1%), were women (66.0%), with secondary education (41.8%), and married (65.5%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic profile of informants of older residents

| informal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| caregivers of | |||||

| older adults | |||||

| sample | with any care | ||||

| (N = 2,421) | need (n = 693) | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Age group (years) | 21–34 | 284 | 11.7 | 46 | 6.6 |

| 35–49 | 588 | 24.3 | 186 | 26.9 | |

| 50–64 | 908 | 37.6 | 312 | 45.1 | |

| 65+ | 638 | 26.4 | 148 | 21.4 | |

| Gender | Women | 1,559 | 64.4 | 457 | 66.0 |

| Men | 861 | 35.6 | 235 | 34.0 | |

| Ethnicity | Chinese | 931 | 38.5 | 230 | 33.2 |

| Malay | 728 | 30.1 | 250 | 36.1 | |

| Indian | 728 | 30.1 | 208 | 30.0 | |

| Others | 34 | 1.4 | 5 | 0.7 | |

| Marital status | Never married | 528 | 21.8 | 180 | 26.1 |

| Married/cohabiting | 1,720 | 71.2 | 452 | 65.5 | |

| Separated/divorced | 116 | 4.8 | 37 | 5.4 | |

| Widowed | 53 | 2.2 | 21 | 3.0 | |

| Having children | No | 686 | 28.4 | 224 | 32.5 |

| Yes | 1,731 | 71.6 | 466 | 67.5 | |

| Education level | None | 80 | 3.3 | 18 | 2.6 |

| Minimal | 213 | 8.8 | 51 | 7.4 | |

| Completed primary | 516 | 21.3 | 137 | 19.8 | |

| Completed secondary | 870 | 36.0 | 289 | 41.8 | |

| Completed tertiary | 740 | 30.6 | 196 | 28.4 | |

| Relationship with the older resident | Spouse | 883 | 36.5 | 131 | 18.9 |

| Son/daughter | 1,082 | 44.7 | 428 | 61.8 | |

| Son/daughter-in-law | 147 | 6.1 | 71 | 10.3 | |

| Sibling | 97 | 4 | 16 | 2.3 | |

| Other relative | 108 | 4.5 | 33 | 4.8 | |

| Friend/neighbor or other | 103 | 4.3 | 13 | 1.9 | |

| Lives with the older resident | No | 425 | 17.6 | 125 | 18.1 |

| Yes | 1,994 | 82.4 | 567 | 81.9 | |

Care need, care arrangement, and care participation of informal caregivers

Out of the 693 older adults with any care need, 330 (47.6%) needed care “much of the time” and 363 (52.4%) needed care “some of the time” (Table 2). Among the older adults with any care need, 356 (51.4%) had dementia. Care needs and care arrangements reported by informal caregivers varied for those without and with dementia. Over 80% of older adults with dementia needed care some or much of the time. Significantly, higher proportion (64.3%) of those with dementia needed care much of the time as compared with 30% of those without dementia. Assistance received by caregivers from other family members or friends was similar in the two groups; however, a significantly higher proportion of informal caregivers of older people with dementia received help from a paid helper (Table 2). The top three care roles undertaken by caregivers of older adults with any care need were communicating with the person (13.5%), supervising the older adult (8.6%), and feeding (3.6%). Except for assistance with transport, statistically significant and higher proportion of caregivers of people with dementia spent time on care tasks, with the highest being for feeding (Table 3).

Table 2.

Care needs and care arrangements reported by informal caregivers (N = 693)

| without | with | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| overall | dementia | dementia | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | p-value | ||

| Care needs | Needs care much of the time | 330 | 47.6 | 101 | 30.0 | 229 | 64.3 | <0.001 |

| Needs care some of the time | 363 | 52.4 | 236 | 70.0 | 127 | 37.7 | ||

| Informal caregivers’ involvement in care | One of the main “hands on” caregivers | 396 | 57.1 | 200 | 59.3 | 196 | 55.1 | <0.001 |

| One of the main “organizational” caregivers | 223 | 32.2 | 84 | 24.9 | 139 | 39.0 | ||

| Only slightly involved in providing or organizing care | 65 | 9.4 | 47 | 13.9 | 18 | 5.1 | ||

| Not at all involved in providing or organizing care | 9 | 1.3 | 6 | 1.8 | 3 | 0.8 | ||

| Who provides “hands on’ care | One or more family members | 442 | 64.8 | 243 | 73.0 | 199 | 57.0 | <0.001 |

| One or more unpaid friends or neighbors | 8 | 1.2 | 7 | 2.1 | 1 | 0.3 | ||

| One or more paid caregivers | 232 | 34 | 83 | 24.9 | 149 | 42.7 | ||

| Given up or cut down on work | Yes, given up | 55 | 8.1 | 22 | 6.7 | 33 | 9.4 | 0.301 |

| Yes, cut down | 76 | 11.2 | 34 | 10.3 | 42 | 12.0 | ||

| No | 550 | 80.8 | 274 | 83.0 | 276 | 78.6 | ||

| Friends or relatives help with care | No | 559 | 80.8 | 277 | 82.2 | 282 | 79.4 | 0.357 |

| Yes | 133 | 19.2 | 60 | 17.8 | 73 | 20.6 | ||

| Paid help during the day | No paid help | 384 | 55.7 | 223 | 66.8 | 161 | 45.4 | <0.001 |

| Occasional | 14 | 2 | 6 | 1.8 | 8 | 2.3 | ||

| Regular | 98 | 14.2 | 37 | 11.1 | 61 | 17.2 | ||

| Constant | 193 | 28 | 68 | 20.4 | 125 | 35.2 | ||

| Paid help during the night | No paid help | 503 | 73.5 | 266 | 80.1 | 237 | 67.3 | <0.001 |

| Sleep-in paid help | 141 | 20.6 | 49 | 14.8 | 92 | 26.1 | ||

| Waking paid help | 40 | 5.8 | 17 | 5.1 | 23 | 6.5 | ||

Table 3.

Informal caregivers’ participation in activities of daily living (ADLs) of older residents (N = 693)

| without | with | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| overall | dementia | dementia | ||||||

| time spent in | ||||||||

| 24 hours | n | % | n | % | n | % | p-value | |

| Communicating | No time | 401 | 59.1 | 235 | 71.4 | 166 | 47.4 | <0.001 |

| with the person | 1 to 2 h | 186 | 27.4 | 69 | 21.0 | 117 | 33.4 | |

| More than 2 h | 92 | 13.5 | 25 | 7.6 | 67 | 19.1 | ||

| Using transport | No time | 599 | 87.4 | 288 | 86.0 | 311 | 88.9 | 0.708 |

| Less than 1 h | 40 | 5.8 | 22 | 6.6 | 18 | 5.1 | ||

| 1 to 2 h | 23 | 3.4 | 13 | 3.9 | 10 | 2.9 | ||

| More than 2 h | 23 | 3.4 | 12 | 3.6 | 11 | 3.1 | ||

| Dressing | No time | 527 | 76.6 | 292 | 87.4 | 235 | 66.4 | <0.001 |

| Less than 1 h | 130 | 18.9 | 34 | 10.2 | 96 | 27.1 | ||

| 1 to 2 h | 21 | 3.1 | 5 | 1.5 | 16 | 4.5 | ||

| More than 2 h | 10 | 1.5 | 3 | 0.9 | 7 | 2.0 | ||

| Feeding | No time | 445 | 64.6 | 258 | 77.0 | 187 | 52.8 | <0.001 |

| Less than 1 h | 172 | 25 | 60 | 17.9 | 112 | 31.6 | ||

| 1 to 2 h | 47 | 6.8 | 10 | 3.0 | 37 | 10.5 | ||

| More than 2 h | 25 | 3.6 | 7 | 2.1 | 18 | 5.1 | ||

| Grooming | No time | 563 | 81.8 | 306 | 91.6 | 257 | 72.6 | <0.001 |

| Less than 1 h | 95 | 13.8 | 22 | 6.6 | 73 | 20.6 | ||

| 1 to 2 h | 18 | 2.6 | 3 | 0.9 | 15 | 4.2 | ||

| More than 2 h | 12 | 1.7 | 3 | 0.9 | 9 | 2.5 | ||

| Supervising the person | No time | 542 | 80.5 | 289 | 87.8 | 253 | 73.5 | <0.001 |

| 1 to 2 h | 73 | 10.8 | 23 | 7.0 | 50 | 14.5 | ||

| More than 2 h | 58 | 8.6 | 17 | 5.2 | 41 | 11.9 | ||

| Helping with toileting | No time | 542 | 78.8 | 296 | 88.6 | 246 | 69.5 | <0.001 |

| Less than 1 h | 98 | 14.2 | 26 | 7.8 | 72 | 20.3 | ||

| 1 to 2 h | 36 | 5.2 | 9 | 2.7 | 27 | 7.6 | ||

| More than 2 h | 12 | 1.7 | 3 | 0.9 | 9 | 2.5 | ||

| Helping with bathing | No time | 526 | 76.2 | 291 | 86.9 | 235 | 66.2 | <0.001 |

| Less than 1 hour | 124 | 18 | 38 | 11.3 | 86 | 24.2 | ||

| 1 to 2 h | 30 | 4.3 | 3 | 0.9 | 27 | 7.6 | ||

| More than 2 h | 10 | 1.4 | 3 | 0.9 | 7 | 2.0 | ||

BPSD and care burden

At least one BPSD was present among 381 (55.2%) of the older adults with care needs with a significantly higher proportion (p < 0.001) among those with dementia (66.1%) versus those without (33.9%). The mean ZBI care burden score among the informal caregivers was 14.0 ± 13.0 (range: 0–88). ZBI scores among caregivers of people without (10.8 ± 10.6) and with dementia (17.0 ± 14.2) differed significantly (p < 0.001). Among the informal caregivers, 24.5% met criterion for care burden.

Correlates of care burden among informal caregivers

The correlates of care burden examined using logistic regression analyses are reported in Table 4. Caregivers with children had 0.4 times lower risk of burden than those without children. Care burden was significantly associated with caregivers’ marital status: compared with those who had never married, married caregivers had a 2.4 times higher risk of burden. Informal caregivers were also more likely to experience care burden if their relative belonged to a younger cohort (2.5 times higher risk among residents aged 60–74 years than those aged 84 years and above), needed care much of the time (2.5 times), exhibited BPSD (3.5 times), and had dementia (2.5 times).

Table 4.

Correlates of care burden assessed by ZBI among informal caregivers of older residents having some or much care need (N = 693)

| or | 95% CI | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver's characteristics | |||||

| Age (years) | 21–34 | Ref. | |||

| 35–49 | 2.6 | 0.8 | 8.1 | 0.099 | |

| 50–64 | 2.3 | 0.7 | 7.2 | 0.168 | |

| 65+ | 1.7 | 0.5 | 6.8 | 0.422 | |

| Gender | Women | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 0.703 |

| Men | Ref. | ||||

| Ethnicity | Chinese | Ref. | |||

| Malay | 0.6 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 0.071 | |

| Indian | 1.2 | 0.7 | 2.1 | 0.458 | |

| Others | 1.8 | 0.1 | 21.8 | 0.657 | |

| Marital status | Never married | Ref. | |||

| Married/cohabiting | 2.4 | 1.1 | 5.5 | 0.034 | |

| Separated/divorced | 1.5 | 0.5 | 4.5 | 0.432 | |

| Widowed | 2.2 | 0.5 | 8.9 | 0.27 | |

| Having children | No | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.006 | |

| Education | None | 1.3 | 0.3 | 5.2 | 0.697 |

| Minimal | 1.0 | 0.4 | 2.6 | 0.93 | |

| Completed primary | 0.8 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 0.567 | |

| Completed secondary | 1.1 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 0.798 | |

| Completed tertiary/further education | Ref. | ||||

| Relationship with the older person | Spouse | Ref. | |||

| Child | 1.4 | 0.6 | 3.5 | 0.448 | |

| Other relative/friend | 0.8 | 0.3 | 2.0 | 0.563 | |

| Lives with the older person | No | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 1.2 | 0.7 | 2.1 | 0.604 | |

| Receives help with care | No | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 1.3 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 0.225 | |

| Older residents’ characteristics | |||||

| Age (years) | 60–74 | 2.5 | 1.3 | 4.9 | 0.006 |

| 75–84 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 2.3 | 0.256 | |

| 85+ | Ref. | ||||

| Gender | Women | 0.9 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 0.705 |

| Men | Ref. | ||||

| Care need | Some | Ref. | |||

| Much | 2.5 | 1.6 | 4.0 | <0.001 | |

| BPSD | None | Ref. | |||

| At least one | 3.5 | 2.2 | 5.6 | <0.001 | |

| Dementia | No | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 2.5 | 1.5 | 4.2 | 0.001 | |

Note: BPSD = Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia.

Discussion

Consistent with the findings from previous research (Prince et al., 2004; Huang et al., 2015; Stoltz et al., 2015), caregivers in our sample participated in various care and related activities for older adults. As expected, care need, assistance with ADLs, and presence of BPSD were significantly higher among older adults with dementia, resulting in higher care participation. For the majority of older adults (65%), hands-on care was provided by one or more of their family members, and for about 20% of them, friends or other relatives also assisted with care. Compared with other studies that have found a proportion ranging from 17–40% (Prince et al., 2004; Brodaty and Donkin, 2009), we had a slightly smaller proportion of caregivers (19.3% of the overall sample and 21.4% of those caring for a person with dementia) who had cut down or given up their work. Regardless, the combined effect of work, need for assistance from other unpaid caregivers, and receipt of help from paid helpers highlight substantial strain among informal caregivers in Singapore, and more so for those caring for an older relative with dementia.

A sizeable proportion of caregivers experienced burden, and this is consistent with other studies (Brodaty and Donkin, 2009; Tew et al., 2010; Prince et al., 2012). The ZBI score among caregivers of people with dementia in our sample was much lower than that reported elsewhere (Hori et al., 2011; Prince et al., 2012; Brodaty et al., 2013). Socio-cultural differences and caregiver characteristics could be possible explanations for this. Lower levels of burden have been reported among Asian and collectivist samples as compared with Western or individualistic populations, which were due to the varying subjective appraisals of care burden in the two cultures and the strong tradition of filial piety among the collectivist societies (Kim et al., 2002; Lai, 2007). Another observation from our study was that for the majority of informal caregivers, there was another member of the family or a paid caregiver to provide help and support (Table 2), and it is possible that the availability of another helper might have resulted in alleviating or lowering the level of burden in our sample, compared with other studies. Lower burden among family members with paid caregivers has been reported from Latin America (Prince et al., 2012) and Japan (Kumamoto et al., 2006).

Several studies that have examined the association between caregiver characteristics and care burden found that kinship ties (spouse, child, and siblings) were an early factor that influence burden among caregivers of older adults, including those with dementia (Almberg et al., 1980; de Vugt et al., 2006). It has been shown that spouses often manifest greater distress and feelings of burden when they alone assume the care of an older individual at home (Vugt et al., 2006). Surprisingly, while we did not observe an association of spousal relationship with care burden in our sample, marital status of caregivers was a strong factor, with higher burden being reported among married caregivers. This finding might have been influenced by the higher proportion of caregivers who were children over spousal caregivers (36%) in our sample. More research is needed in understanding the independent association of spousal relationship over marital status with care burden.

Another finding was the lack of association of caregivers’ gender and education with burden. While there is substantial evidence in literature that female caregivers experience more stress than male caregivers (Gallicchio et al., 2002; Croog et al., 2006), not all studies report clear-cut gender differences (Annerstedt et al., 2000; Chumbler et al., 2003). It is hypothesized that gender may influence the experience of care burden; compared with female caregivers who used emotion-focused coping strategies, male caregivers, on the other hand, tend to adopt more problem-focused coping strategies, which are found to be most effective in reducing strain on caregivers (Almberg et al., 1997). In contrast with other reports which have shown higher burden among primary caregivers with children, we found an inverse association, with lower risk among those with children. Additional care support received from their children could be one of the reasons; however, we did not capture this data specifically in our study. An earlier study has also posited less care burden when more visits were paid by other relatives, particularly children, to the dementia patient (Zarit et al., 1980).

More caregivers of younger older adults experienced burden than those caring for much older individuals. This is in contrast with a number of studies that have reported higher burden among caregivers of older adults. Miyamoto et al. (2002) found that caregivers of mobile patients with dementia reported higher amounts of care burden because of more behavioral disturbances than non-mobile patients. More behavioral disturbances have been reported among younger patients with dementia (Beeri et al., 2002), which could possibly explain our finding.

Consistent with previous studies (Beeri et al., 2002; Sink et al., 2005; Tew et al., 2010; Prince et al., 2012), our study found that the presence of BPSD, care need, and dementia in older adults are significant factors contributing to care burden. The effects of BPSD have been reported to be independent and more prominent factors for care burden than cognitive deficits or dementia (Arango, 2009; Prince et al., 2012). We found an almost four times higher risk for burden (among the caregivers of older adults with BPSD as compared with twice the risk for dementia (odds ratio (OR) 2.5). BPSD have also been associated with higher care needs (Kinoshita, 2008; Jeon et al., 2013), further compounding the strain on caregivers, and thus increasing their burden.

A significant strength of the study is the use of a population-based sample with the ability to include older adults needing care and their caregivers not known to the care system – reflecting a broader picture of the situation among informal caregivers. The study also investigated a wider range of correlates of care burden by including multiple factors related to the caregivers themselves, older adults and their care needs, and clinical characteristics such as BPSD and dementia diagnosis.

However, certain limitations need to be considered while interpreting the study findings. This being a cross-sectional study, temporal and causal relationships could not be established. The definition of informal caregivers used in the study was broad – someone who “knew the older person best,” so that they could provide adequate information on older adults’ health status during the survey. The informal caregivers in our study were therefore not necessarily their primary caregivers and this might have influenced some of the observed associations. In addition, a sizeable proportion of older adults in our sample, in particular those with dementia, were cared for by paid helpers and we did not include paid helpers in our study. Caregivers’ participation in ADLs was assessed by estimating the time they spent in the last 24 h before the interview and this might not have adequately covered care provided on an ad hoc basis on other days or on a typical day by them leading to under- or over-reporting of the true time spent. Lastly, we could not examine the effect of total time spent on caring, which is an important mediator of care burden as it was not possible to compute the care time accurately due to the categorical nature of responses to care participation and assistance in ADLs.

Conclusions

This work contributes to improving knowledge concerning care situations of older adults with care needs and care burden experienced by their informal caregivers. The study used large-scale, population-based data that included a number of factors related to care burden after controlling for relevant covariates that ensure generalizability to a wide range of caregiving situations, and broaden our understanding of caregivers’ experienced burden, specifically for those caring for an older adult with dementia. The study has several important implications. The study provides recent information on the scale of caregivers’ burden after taking into account multiple factors, and highlights the need for its assessment in routine clinical practice. We also identified groups at higher risk – married caregivers and caregivers of older adults with more care needs, BPSD, and dementia; and these should be considered while planning interventions to alleviate care burden. The adoption of caregiver support programs for families of older adults with dementia may be able to impact on these findings and improve the experience of their informal caregivers.

Conflict of interest

None.

Description of authors’ roles

Janhavi Ajit Vaingankar designed the study, collected, verified, and analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. Siow Ann Chong and Edimansyah Abdin assisted in study design, interpreted the data, and provided intellectual inputs on the manuscript. Louisa Picco, Anitha Jeyagurunathan, YunJue Zhang, Rajeswari Sambasivam, and Boon Yiang Chua played an active role in data collection, clean up, refining analysis plan, and drafting the manuscript. Li Ling Ng provided clinical inputs into the findings and edited the manuscript. Martin Prince designed and developed the study questionnaires, provided intellectual inputs into the study design, analysis plan, and interpretation of findings. Mythily Subramaniam supervised the overall study design, provided inputs on the manuscript content, and approved the manuscript version to be published.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the Ministry of Health, Singapore and Singapore Millennium Foundation of the Temasek Trust.

References

- Almberg B., Grafström M. and Winblad B. (1997). Major strain and coping strategies as reported by family members who care for aged demented relatives. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 26, 683–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annerstedt L., Elmstahl S., Ingvad B. and Samuelsson S. (2000). Family caregiving in dementia – an analysis of the caregiver's burden and the “breaking-point” when home care becomes inadequate. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 28, 23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bähler C., Huber C. A., Brüngger B. and Reich O. (2015). Multimorbidity, health care utilization and costs in an elderly community-dwelling population: a claims data based observational study. BMC Health Services Research, 22, 15–23. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0698-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeri M. S., Werner P., Davidson M. and Noy S. (2002). The cost of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in community dwelling Alzheimer's disease patients. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17, 403–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodaty H. and Donkin M. (2009). Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 11, 217–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodaty H., Woodward M., Boundy K., Ames D. and Balshaw R. (2014). PRIME study group prevalence and predictors of burden in caregivers of people with dementia. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 22, 756–765. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chumbler N., Grimm J., Cody M. and Beck C. (2003). Gender, kinship, and caregiver burden: the case of community-dwelling, memory-impaired seniors. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18, 722–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croog S. H., Burleson J. A., Sudilovsky A. and Baume R. M. (2006). Spouse caregivers of Alzheimer patients: problem responses to caregiver burden. Aging and Mental Health, 10, 87–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de, Vugt M. E., Riedijk S. R., Aalten P., Tibben A., van, Swieten J. C. and Verhey F. R. (2006). Impact of behavioral problems on spousal caregivers: a comparison between Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 22, 25–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkin J. J. and Anderson-Hanley C. (1998). Dementia caregiver burden: a review of the literature and guidelines for assessment and intervention. Neurology, 51:S53–S60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etters L., Goodall D. and Harrison B. E. (2008, August). Caregiver burden among dementia patient caregivers: a review of the literature. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 20, 423–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallicchio L., Siddiqi N., Langenberg P. and Baumgarten M. (2002). Gender differences in burden and depression among informal caregivers of demented elders in the community. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17, 154–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonyea J. G., O’Connor M., Carruth A. and Boyle P. A. (2005). Subjective appraisal of Alzheimer's disease caregiving: the role of self-efficacy and depressive symptoms in the experience of burden. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias, 20, 273–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori Y., Hoshino J. and Suzuki K. (2011). Physical and psychological health problems among Japanese family caregivers. Nagoya Journal of Medical Science, 73, 107–115. Available at: http://www.singstat.gov.sg/publications/publications-and-papers/population-and-population-structure/population-trends, last accessed 28 June 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H. L. et al. (2015). Family caregivers’ role implementation at different stages of dementia. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 5, 135–146. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S60574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda C. et al. (2015). Difference in determinants of caregiver burden between amnestic mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer׳s disease. Psychiatry Research, 30, 226, 242–246. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inter-Ministerial Committee (IMC). Report on the Ageing Population Available at http://app.msf.gov.sg/Research-Room/Research-Statistics/IMC-Report-on-the-Ageing-Population, last accessed 28 June 2015.

- Jeon Y. H. et al. (2013). Care planning practices for behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in residential aged care: a pilot of an education toolkit informed by the Aged Care Funding Instrument. Contemporary Nurse, 44, 156–169. doi: 10.5172/conu.2013.44.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufer D. I. et al. (2000). Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 12, 233–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. M., Shin I. S., Jeong S. J., Gormley N. and Yoon Y. S. (2002). Predictors of institutionalization in patients with dementia in Korea. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17, 101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T. (2008). Role of the home visit medical service for patients with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) living in the community. Psychogeriatrics, 8, 142–147. [Google Scholar]

- Kumamoto K., Arai Y. and Zarit S. H. (2006). Use of home care services effectively reduces feelings of burden among family caregivers of disabled elderly in Japan: preliminary results. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 21, 163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai D. W. (2007). Cultural predictors of caregiving burden of Chinese-Canadian family caregivers. Canadian Journal of Aging, 26, S133–S147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta K. K. (2005). Stress among family caregivers of older persons in Singapore. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 20, 319–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto Y., Ito H., Otsuka T. and Kurita H. (2002). Caregiver burden in mobile and non-mobile demented patients: a comparative study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17, 765–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phung K. T. et al. (2014). Validation of the 10/66 Dementia Research Group diagnostic assessment for dementia in Arabic: a study in Lebanon. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 27, 282–290. doi: 10.1177/0891988714532019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince M. and 10/66 Dementia Research Group (2004). 10/66 Dementia Research Group. Care arrangements for people with dementia in developing countries. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 19, 170–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince M. et al. (2007). The protocols for the 10/66 dementia research group population-based research programme. BMC Public Health, 20, 165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince M. J. et al. (2008). The 10/66 Dementia Research Group's fully operationalised DSM-IV dementia computerized diagnostic algorithm, compared with the 10/66 dementia algorithm and a clinician diagnosis: a population validation study. BMC Public Health, 8, 219. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince M. et al. (2012). Strain and its correlates among carers of people with dementia in low-income and middle-income countries. A 10/66 Dementia Research Group population-based survey. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27, 670–682. doi: 10.1002/gps.2727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi P. et al. (2005). Predictors of high level of burden and distress in caregivers of demented patients: results of an Italian multicenter study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 20, 168–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner A. S., Morimoto T., Arai Y. and Zarit S. (2006). Assessing family caregiver's mental health using a statistically derived cut-off score for the Zarit Burden Interview. Aging and Mental Health, 10, 107–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seng B. K. et al. (2010). Validity and reliability of the Zarit Burden Interview in assessing caregiving burden. Annals of the Academy of Medicine Singapore, 39, 758–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sink K. M., Holden K. F. and Yaffe K. (2005). Pharmacological treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: a review of the evidence. Journal of the American Medical Association, 293, 596–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltz P., Udén G. and Willman A. (2004). Support for family carers who care for an elderly person at home – a systematic literature review. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 18, 111–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam M. et al. (2015). Prevalence of dementia in people aged 60 years and above: results from the WiSE Study. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 45, 1127–1138. doi: 10.3233/JAD-142769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan L. L., Wong H. B. and Allen H. (2005). The impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia on distress in family and professional caregivers in Singapore. International Psychogeriatrics, 17, 253–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tew C. W., Tan L. F., Luo N., Ng W. Y. and Yap P. (2010). Why family caregivers choose to institutionalize a loved one with dementia: a Singapore perspective. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 30, 509–516. doi: 10.1159/000320260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit S. H., Reever K. E. and Back-Peterson J. (1980). Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. The Gerontologist, 20, 649–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]