Abstract

Chronic migraine is a costly and highly disabling condition that impacts millions of people in the United States. While chronic migraine is hypothesized to result from more infrequent forms of migraine, the precise mechanism by which this develops is still being researched. This study sought to better characterize the treatment patterns, disorder characteristics, and medical and disability profile of the chronic migraine population using the largest dataset of chronic migraineurs ever collected. The survey was started by 8,359 individuals and 4,787 met the inclusion criteria for diagnosed chronic migraine The number of stressful life events participants experienced due to their migraines related to number of therapies tried (p<0.00, eta2=0.215), depression (p<0.00, eta2=0.178), number of comorbidities (p<0.00, eta2=0.172), anxiety (p<0.00, eta2=0.162), number of physician visits in the past year (p<0.00, eta2=0.103), and chronic pain levels (p<0.00, eta2=0.077).. The results of this survey suggest that chronic migraineurs may misattribute aspects of psychiatric or medical comorbidities to their chronic migraines. Further, the sample underutilized mental health services and were unsatisfied with their migraine treatments. Providers to chronic migraineurs should ensure that patients are receiving appropriate mental health care in order to alleviate psychological distress as well as to potentially lessen negative life events previously associated with migraine symptoms.

Keywords: Chronic migraine, Headache, Mental health services, Psychiatric symptoms

Introduction

Migraine headache is a prevalent chronic pain condition that afflicts millions of Americans with prevalence estimates ranging between 16.2% and 22.7% of adults in the United States [1]. Migraine, however, is not a homogeneous disorder but instead is grossly subdivided into two groups: episodic migraine and chronic migraine.

Chronic migraine is the most severe manifestation of migraine and has been found to impart large costs on individuals and society at large with an overall prevalence rate of about 2% [2]. Individuals with chronic migraine have been found to be significantly more disabled than episodic migraineurs with a higher degree of impairment to their daily activities [3,4], have significantly worse medical outcomes, and use healthcare resources at a rate of four times that of episodic migraineurs [5]. Further, chronic migraineurs have been found to experience higher indirect costs of their migraines when compared with episodic migraineurs [6]. Chronic migraineurs have been found to experience lower socioeconomic status and greater psychiatric and medical comorbidities when compared to episodic migraineurs [5].

Chronic migraine is currently differentiated from other forms of migraine based almost exclusively on the frequency of migraine symptoms, however, whether chronic migraine is a distinct entity from other forms of migraine is still debated [5]. Some researchers have argued that migraine is a spectrum of illness with chronic migraine as its most extreme form. This viewpoint is supported by biological research showing that chronic migraine is associated with abnormalities in periaqueductal grey matter damage that may develop progressively in milder forms of migraine [7], both forms show similar patterns of cortical excitability between chronic and episodic migraine [8], and abnormal hypothalamic hormone secretion [9]. Chronic migraine may also be a progression of episodic migraine resulting from medication overuse [10] depression [11], and qualitative disability aspects [12,13]. A smaller number of researchers have argued that chronic migraine is far more distinct from episodic migraine than simple migraine frequency due to distinct biomarkers [14], the unique degradation of the endocannabinoid system in chronic migraine [14,15], different sociodemographic and comorbidity profiles [16], and health quality of life and headache related burden [5].

Whether chronic migraine is an extreme manifestation of the experience of episodic migraine, a distinct neurological or biological entity, or a combination of those etiologies is important, however, research has shown that chronic migraine is understudied and that more information is needed about chronic migraineurs [16]. Knowledge of the comorbid disorders experienced by chronic migraineurs, their treatment patterns, and migraine characteristics, can help inform and improve the treatment satisfaction and care of this group. Previous studies which sought to characterize chronic migraineurs have based their findings on relatively small sample sizes drawn from large survey datasets [17,18]. Chronic migraine is currently thought to be a preventable disorder, so long as appropriate treatment is identified early enough in the development of the disorder and understanding the experience of chronic migraineurs could have vast implication in reducing the individual and societal burdens of chronic migraine [5,19,20].

The personal and societal costs of chronic migraine as well as the previously reported low treatment satisfaction and adherence rates emphasize the need to understand the treatment patterns of this highly disabled population [17]. This need is emphasized with the observation that chronic migraine may progress from or be the result of treatable conditions. The current study extends the available literature by describing the disability profile, migraine characteristics, stress events, treatment patterns, and comorbidity profile of chronic migraineurs. Significantly, the sample reported in this paper is far larger than in any previously reported chronic migraine research.

Method

Recruitment

Participants were recruited from a well-known online migraine headache resource. Adults aged 18 years or older and who currently live in the United States were invited to participate. The presence of chronic migraines was validated through agreement with the statement “Have you ever been diagnosed with chronic migraine by a physician?”

Procedure

This study was approved by the University of Massachusetts Institutional Review Board. An online survey was presented by a migraine-specific community website over 30 days between July and August 2014. Participants were informed that their participation was voluntary, information would be collected anonymously, the anticipated completion time of the survey, and that they would not receive compensation for participating. No personal identifiers were collected nor solicited from participants. The survey contained questions related to demographic information, migraine history and symptoms, social information, and treatment history and satisfaction. The survey host used embedded cookies to prevent a participant from taking the survey multiple times. The survey employed an adaptive survey methodology. Data was collected by the survey host and stored on secure servers.

Data analysis

All data analysis was performed using SPSS 22.0. Participant demographics were analyzed using descriptive statistics and Analysis of Variance analyses were used to examine the relationships among survey data.

Results

Participants

The survey was started by 8,359 individuals. A total of 3,443 individuals were excluded due to: not consenting to participate (n=128), not living in the United States of America (n=677), less than 18 years old (n=69), not currently suffering from migraine (n=57), or not diagnosed with chronic migraine (n=2,449). Of the remaining 4,787 individuals, 3,788 completed it (79.1% completion rate). The mean time to complete the survey was 46.5 minutes (SD=2 hr 0 min 41 sec). Due to the use of adaptive survey methodology, participants did not answer questions that were not relevant to their experience which resulted in a small variation in the number of responses per question.

Demographics

The sample was 95.1% female and over half of the sample (52.6%) was older than 45 years. Most of the sample (55.8%) had experienced their first migraine symptoms more than 21 years ago and 70.2% had been diagnosed with any type of migraine more than 10 years ago. 33.8% of participants reported being diagnosed with a subtype of migraine and of those individuals, 19.8% reported being diagnosed with Migraine with Aura (ICD-10 G43.1). Additional demographic information can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and disease characteristics.

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 233 | 4.9 |

| Female | 4554 | 95.1 |

| Age in Years | ||

| <18 | 69 | (Excl) |

| 18–24 | 258 | 3.2 |

| 25–34 | 1054 | 13.2 |

| 35–44 | 2471 | 30.9 |

| 45–54 | 2405 | 30.1 |

| 55–64 | 1416 | 17.7 |

| >65 | 390 | 4.8 |

| First Migraine Symptoms | ||

| <1 year | 28 | 0.6 |

| 1–5 years | 343 | 7.3 |

| 6–10 years | 479 | 10.0 |

| 11–15 years | 588 | 12.3 |

| 16–20 years | 672 | 14.0 |

| 21 or more years | 2671 | 55.8 |

| US Resident | ||

| Live in USA or its territories | 7386 | 100 |

| US citizen living abroad | 167 | (Excl) |

| Do not live in USA and not a US citizen | 510 | (Excl) |

| Ever been diagnosed with chronic migraine by physician | ||

| Yes | 4619 | 100 |

| No | 2449 | (Excl) |

| Diagnosed with another type of migraine at any point | ||

| Yes | 1618 | 33.8 |

| No | 1782 | 37.2 |

| Not sure | 1387 | 29.0 |

| What other type of migraine were you diagnosed with? (ICD-10 code) | ||

| Episodic Migraine (G43.909) | 892 | 18.6 |

| Migraine without Aura (G43.00) | 655 | 13.7 |

| Menstrual Migraine (G43.82) | 533 | 11.1 |

| Migraine With Aura (G43.1) | 947 | 19.8 |

| Migraine with Typical Aura (G43.109) | 159 | 3.3 |

| Migraine with Brainstem Aura (G43.109) | 96 | 2.0 |

| Hemiplegic Migraine (G43.4) | 243 | 5.1 |

| Retinal Migraine (G43.1) | 200 | 4.2 |

| Abdominal Migraine (G43.D) | 116 | 2.4 |

Comorbid disorders

Data relating to reported comorbid disorders can be seen in Table 2. Over half of the sample had been diagnosed with depression (59.1%) and anxiety (56.4%). The next most frequently reported comorbid disorder was chronic pain at 38.2%. 21.1% of participants reported carrying a diagnosis of chronic fatigue.

Table 2.

Comorbid disorders.

| Comorbidity | N | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Depression | 2830 | 59.1 |

| Anxiety | 2699 | 56.4 |

| Stroke | 145 | 3.0 |

| Epilepsy | 93 | 1.9 |

| Hypertension | 972 | 20.3 |

| Diabetes | 250 | 5.2 |

| Bipolar Disorder | 253 | 5.3 |

| IBS | 1282 | 26.8 |

| Crohn’s Disease | 44 | 0.9 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 87 | 1.8 |

| High Cholesterol | 920 | 19.2 |

| Chronic Pain | 1827 | 38.2 |

| Fibromyalgia | 847 | 17.7 |

| Thyroid Disease | 784 | 16.4 |

| Chronic Fatigue | 1010 | 21.1 |

| Asthma | 763 | 15.9 |

| COPD | 87 | 1.8 |

| Hepatitis | 41 | 0.9 |

| Sleep Disorders | 1447 | 30.2 |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | 182 | 3.8 |

| Multiple Sclerosis | 21 | 0.4 |

| Autoimmune Disorder | 218 | 4.6 |

| PTSD | 497 | 10.4 |

| OCD | 318 | 6.6 |

| Panic Disorder | 643 | 13.4 |

| Phobia | 185 | 3.9 |

| Borderline-Personality Disorder | 74 | 1.5 |

| Substance Abuse | 136 | 2.8 |

| Pancreatitis | 62 | 1.3 |

Negative life events

A majority of participants endorsed the following statements describing negative impacts resulting from their migraine: migraines have impacted my work/career (69.2%), people don’t believe that my migraines are severe (64.3%), and constantly worried about disappointing people (53.5%).

A composite variable named “Negative Life Events Score” was created using items from the survey which examined specific areas of life impacted by participant migraines (Cronbach’s alpha=0.837). The Negative Life Events Score was found to have a mean of 4.92 (SD=3.458; Possible Range: 0–13; Observed Range: 0–13). The results of questions assessing the impact of chronic migraine on participant’s lives can be found in Table 3. The results of the ANOVA analyses identifying relationships among the Negative Life Events Score and a variety of migraine and medical aspects can be seen in Table 4. The Negative Life Events Score was found to be account for a high degree of variance in depression (p<0.000, eta2=0.1782), anxiety (p<0.000, eta2=0.1620), IBS (p<0.000, eta2=0.0379), chronic pain (p<0.000, eta2=0.0768), the total number of reported comorbidities (p<0.000, eta2=0.1717), total number of therapies tried (p<0.000, eta2=0.2147), and how many times in the past year that the participant had seen their physician (p<0.000, eta2=0.1034).

Table 3.

Negative life events.

| Event | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| People don’t believe that my migraines are severe | 3080 | 64.3 | |

| I’m constantly worried about disappointing people | 2559 | 53.5 | |

| Migraines have impacted my work/career | 3313 | 69.2 | |

| Migraines affect my ability to maintain relationships | 2036 | 42.5 | |

| Migraines impact my relationship with my child/children | 1890 | 39.5 | |

| I feel like others blame me for my migraines | 1757 | 36.7 | |

| Sometimes I blame myself for my migraines | 1467 | 30.6 | |

| Friends/family/colleagues treat me differently because of my migraines | 1888 | 39.4 | |

| Doctors treat me differently because of my migraines | 1418 | 29.6 | |

| I feel embarrassed about having migraines | 1449 | 30.3 | |

| I have lost a job due to migraines | 1241 | 25.9 | |

| I’ve lost friends due to my migraines | 1086 | 22.7 | |

| Migraines contributed to my divorce/separation | 351 | 7.3 | |

| Mean | SD | Range | |

| Negative life events score total score | 4.92 | 3.458 | 0–13 |

Table 4.

ANOVA analysis of negative life events score triad by comorbid disorders.

| F(df-btw, df-tot) | p | Eta2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | 207.337(13, 4786) | 0.000 | 0.1782 |

| Anxiety | 184.854(13, 4786) | 0.000 | 0.1620 |

| Stroke | 3.484(13, 4786) | 0.002 | 0.0036 |

| Epilepsy | 1.861(13, 4786) | 0.099 | 0.0019 |

| Hypertension | 16.967(13, 4786) | 0.000 | 0.0174 |

| Diabetes | 5.084(13, 4786) | 0.000 | 0.0053 |

| Bipolar | 10.781(13, 4786) | 0.000 | 0.0112 |

| IBS | 37.635(13, 4786) | 0.000 | 0.0379 |

| Crohn’s Disease | 2.505(13, 4786) | 0.018 | 0.0026 |

| Cardiovascular Disease | 3.049(13, 4786) | 0.010 | 0.0032 |

| High Cholesterol | 13.037(13, 4786) | 0.000 | 0.0135 |

| Chronic Pain | 79.545(13, 4786) | 0.000 | 0.0768 |

| Fibromyalgia | 18.310(13, 4786) | 0.000 | 0.0188 |

| Thyroid Disease | 14.204(13, 4786) | 0.000 | 0.0146 |

| Chronic Fatigue | 33.658(13, 4786) | 0.000 | 0.0340 |

| Asthma | 13.070(13, 4786) | 0.000 | 0.0135 |

| COPD | 1.992(13, 4786) | 0.026 | 0.0021 |

| Hepatitis | 1.092(13, 4786) | 0.273 | 0.0011 |

| Sleep Disorders | 50.430(13, 4786) | 0.000 | 0.0501 |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | 5.370(13, 4786) | 0.003 | 0.0056 |

| Multiple Sclerosis | 2.781(13, 4786) | 0.846 | 0.0029 |

| Autoimmune Disorder | 4.672(13, 4786) | 0.000 | 0.0049 |

| PTSD | 22.716(13, 4786) | 0.000 | 0.0232 |

| OCD | 15.546(13, 4786) | 0.000 | 0.0150 |

| Panic Disorder | 37.606(13, 4786) | 0.000 | 0.0378 |

| Phobia | 13.026(13, 4786) | 0.000 | 0.0134 |

| Borderline Personality Disorder | 2.732(13, 4786) | 0.000 | 0.0029 |

| Substance Abuse | 8.240(13, 4786) | 0.000 | 0.0085 |

| Pancreatitis | 1.890(13, 4786) | 0.115 | 0.0020 |

| Total Number of Reported Comorbidities | 198.156 (5, 4786) | 0.000 | 0.1717 |

| Total Number of Therapies Tried | 261.405(5, 47860) | 0.000 | 0.2147 |

| Age | 13.679 (13, 4786) | 0.000 | 0.0359 |

| How long ago did you first start experiencing migraine symptoms? | 1.273 (13, 4786) | 0.221 | 0.0035 |

| How long ago were you first diagnosed with migraine? | 0.614 (13, 4786) | 0.845 | 0.0017 |

| How many times in the past year would you estimate that you have been to see your physician? | 37.933 (13, 4290) | 0.000 | 0.1034 |

| How many times in the past year have you been to an emergency room or urgent care facility for your headache/migraine? | 14.592 (13, 4290) | 0.325 | 0.0425 |

Migraine symptoms

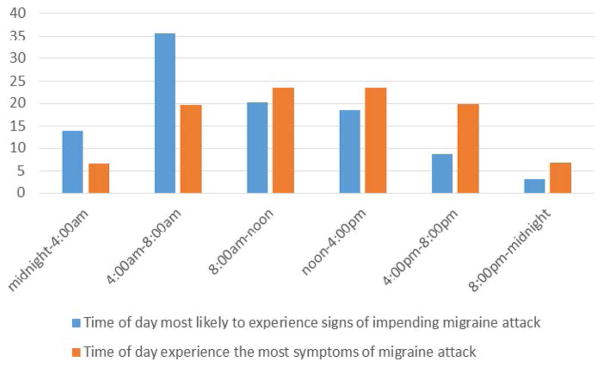

Data relating to migraine symptomology is reported in Tables 5 and 6. Migraine aura was experienced at different rates within the sample with 19.6% of participants reporting that they never experienced aura with their migraines and a further 43.1% of participants reporting that they experienced an aura with their migraines “sometimes”. Head pain was the most commonly endorsed migraine symptom at 84.5% and sensitivity to light was the second most endorsed symptom at 80.1%. Just under half of the sample (45.1%) reported that they currently experience migraine symptoms at a lower frequency than before and of that group only 28.4% attributed finding the right medical approach for the symptom reduction. 48.6% of the sample was able to identify a time of day when they are more likely to experience the signs of an impending migraine attack with 55.8% endorsing the time period of 4:00 am–12:00 pm as the time they are most likely to experience the signs of a migraine attack. Please see Figure 1 for data relating to migraine signs and symptoms by time of day.

Table 5.

Migraine symptoms.

| Symptoms | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Do you experience an aura with your migraines? | ||

| Always | 544 | 13.1 |

| Most Times | 1000 | 24.2 |

| Some Times | 1784 | 43.1 |

| Never | 809 | 19.6 |

| Head pain | 4045 | 84.5 |

| Sensitivity to light | 3832 | 80.1 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 3384 | 70.7 |

| Diarrhea/constipation | 1342 | 28.0 |

| Diff Concentrating | 3420 | 71.4 |

| Fatigue | 3232 | 67.5 |

| Neck pain | 3076 | 64.3 |

| Dizziness/lightheadedness | 2588 | 54.1 |

| Sensitivity to sound | 3555 | 74.3 |

| Visual Changes | 2453 | 51.2 |

| Weakness | 1984 | 41.4 |

| Mood Changes | 2554 | 53.4 |

| Sensitivity to Smell | 2868 | 59.9 |

| Numbness/tingling | 1522 | 31.8 |

| Vertigo | 1425 | 29.8 |

| Puffy Eyelid | 1067 | 22.3 |

| Food Craving | 1001 | 20.9 |

| Other | 781 | 16.3 |

Table 6.

Reasons for decreases in migraine symptom frequency.

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Currently Experience the highest level of migraine symptoms | 2615 | 54.6 |

| Reasons for symptom decrease | ||

| Symptoms decreased on their own | 160 | 3.3 |

| Symptoms decreased because of right non-pharmacological approach | 561 | 11.7 |

| Found the right medicinal approach | 1360 | 28.4 |

| Found the right doctor | 809 | 16.9 |

| Found out how to avoid specific | 1068 | 22.3 |

| Decreased as I got older | 210 | 4.4 |

| Psycho-social approach to pain | 77 | 1.6 |

| Psychotherapy | 81 | 1.7 |

| Stress management | 559 | 11.7 |

| Symptoms decreased due to another reason | 522 | 10.9 |

Figure 1.

Migraine symptoms and attacks by time of day.

Migraine triggers

82.9% of the sample were able to identify at least one trigger for their migraines. Stress was the most common trigger among this sample at 55.8%. The next most commonly endorsed migraine trigger was lack of sleep at 51.9%. 63.4% of participants had taken active steps to avoid triggers for their migraines. Data relating to migraine triggers can be seen in Table 7.

Table 7.

Migraine triggers.

| Migraine Triggers | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Identified any Triggers | 3416 | 82.9 |

| Stress | 2669 | 55.8 |

| Environment (weather, etc…) | 2870 | 60.0 |

| Lack of Sleep | 2484 | 51.9 |

| Hormones/menstrual cycle | 1792 | 37.4 |

| Certain food drink | 2138 | 44.7 |

| Missing meals | 1884 | 39.4 |

| Certain smell | 2046 | 42.7 |

| Alcohol/drugs | 1235 | 25.8 |

| Physical Activity | 1241 | 25.9 |

| Sexual Activity | 325 | 6.8 |

| Other | 739 | 15.4 |

| Steps taken to avoid triggers | 3033 | 63.4 |

Migraine treatments

87.8% of the sample reported consulting a physician for treatment of their migraine and of those 89.3% currently receive treatment from a physician for their migraines. A majority (61.7%) of participants reported disagreeing with a physician about their migraine treatment at some point with the most highly endorsed reason for disagreement being the participant’s previous experience with a treatment that failed (30.5%). 26.1% of participants have used a medication that was not prescribed for their migraine to alleviate their symptoms. A majority of participants have avoided the use of a migraine medication because of its side effects (66.8%) and 75.1% of the sample have discontinued use of a medication because of its side effects. Nearly a third of the sample (30.5%) currently use four or more prescription medications to treat their migraines and 18.9% spend $250 or more per month on these medications and other care for their migraines. Approximately half (48.2%) of the sample used abortive treatment immediately to treat their migraine symptoms; among those who did not use abortive treatment immediately 25.9% did not want to overuse their medication and 22.7% wanted to wait to see if the headache became severe because they did not want to waste a limited supply of medication. Nearly half (48.1%) of the sample “always” incorporates non-pharmacological therapies into their migraine care with dark room being the most used therapy (68.5%). Data relating to physicians consulted about migraine, medical treatments, and therapies, can be seen in Tables 8–10.

Table 8.

Physicians consulted about migraine.

| N | % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you currently see a physician for migraine | 3749 | 89.3 | ||

| Ever disagreed with a physician about migraine treatment | 2307 | 61.7 | ||

| Meds not strong enough | 799 | 16.7 | ||

| Previous experience with treatment failed | 1459 | 30.5 | ||

| Demanded too much time/energy to follow through | 182 | 3.8 | ||

| Not covered by insurance | 441 | 9.2 | ||

| Other reason | 825 | 17.2 | ||

| Reasons a Physician is not Consulted | ||||

| Inconvenience/time issues | 18 | 4.0 | ||

| Financial/Cost/Insurance issues | 162 | 35.8 | ||

| Can’t find the right doctor | 80 | 17.7 | ||

| It never occurred to me | 7 | 0.1 | ||

| Other | 185 | 40.9 | ||

| Physicians | Physicians Ever Consulted | Physicians Currently Treating | ||

| N | % | N | % | |

| PCP/internist | 3875 | 80.9 | 1798 | 37.6 |

| Ob/Gyn | 1159 | 24.2 | 122 | 2.5 |

| Neurologist | 3741 | 78.1 | 2274 | 47.5 |

| Headache Specialist | 2003 | 41.8 | 992 | 20.7 |

| Other physician | 814 | 17.0 | 369 | 7.7 |

Table 10.

Non-prescription therapies.

| Therapies tried | Currently Use therapies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Acupuncture | 1386 | 29.0 | 241 | 5.0 |

| Dark room | 3672 | 76.7 | 3277 | 68.5 |

| Diet | 2634 | 55.0 | 1809 | 37.8 |

| hot/cold therapy | 3223 | 67.3 | 2677 | 55.9 |

| Magnesium | 2387 | 49.9 | 1353 | 28.3 |

| Riboflavin/B2 | 1511 | 31.6 | 743 | 15.5 |

| Psychotherapy/pain psychologist | 800 | 16.7 | 245 | 5.1 |

| Biofeedback/EEG/EMG | 932 | 19.5 | 176 | 3.7 |

| Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation | 204 | 4.3 | 70 | 1.5 |

| Light Therapy | 265 | 5.5 | 102 | 2.1 |

| Herbals | 1570 | 32.8 | 616 | 12.9 |

| Movement Therapy-PT/Yoga… | 1024 | 21.4 | 415 | 8.7 |

| Massage | 2488 | 52.0 | 1244 | 26.0 |

| Energy Therapy - Reiki | 365 | 7.6 | 99 | 2.1 |

| Spiritual/religious resources | 744 | 15.5 | 515 | 10.8 |

| other | 807 | 16.9 | 598 | 12.5 |

| How often are non-medicinal therapies used | ||||

| N | % | |||

| never | 279 | 7.2 | ||

| rarely | 198 | 5.1 | ||

| half the time | 501 | 13.0 | ||

| most times | 1024 | 26.5 | ||

| always | 1855 | 48.1 | ||

Treatment satisfaction

Chronic migraineur satisfaction with treatment appeared to depend greatly on the aspect of their care that they were being asked about. A majority (62.1%) of the sample was either satisfied or very satisfied with their current physician treating their migraine, however, only 29.4% of the sample was satisfied or very satisfied with their medical treatment for their migraines. 21.9% of participants were satisfied or very satisfied with their non-pharmacological migraine therapy. Data related to treatment satisfaction can be found in Table 11.

Table 11.

Treatment satisfaction.

| Treatment Satisfaction | How satisfied are you with your current non-prescription therapies for migraine | How satisfied with current physician | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Extremely Satisfied | 182 | 4.5 | 101 | 2.6 | 1064 | 28.5 |

| Satisfied | 1010 | 24.9 | 757 | 19.3 | 1256 | 33.6 |

| Neutral | 1426 | 35.2 | 1777 | 45.4 | 947 | 25.3 |

| Dissatisfied | 878 | 21.7 | 820 | 21.0 | 333 | 8.9 |

| Extremely Dissatisfied | 523 | 12.9 | 328 | 8.4 | 138 | 3.7 |

| Not applicable | 35 | 0.9 | 130 | 3.3 | 450 | 9.7 |

Health care utilization

Nearly half of the sample (48.6%) visited their physician five or more times in the past year specifically for their migraines. 43% of the sample visited an emergency room or urgent care facility at least once in the past year to receive treatment for a migraine, and of that group a third (33.6%) visited the urgent care facility four or more times. Additional information about emergency health care use can be found in Table 12.

Table 12.

Emergency healthcare.

| How many times in the past year would you estimate that you have been to see your physician (not counting any emergency room visits) regarding your headache/migraine? | ||

| N | % | |

| 1 or less | 549 | 12.8 |

| 2 | 493 | 11.5 |

| 3 | 495 | 11.5 |

| 4 | 668 | 15.6 |

| 5 or more | 2068 | 48.6 |

| Have you been to an emergency room or urgent care facility in the past year for your headache/migraine? | ||

| N | % | |

| Yes | 2057 | 43.0 |

| How many times in the past year have you been to an emergency room or urgent care facility for your headache/migraine? | ||

| N | % | |

| 1 | 547 | 26.6 |

| 2 | 495 | 24.1 |

| 3 | 321 | 15.6 |

| 4 or more | 690 | 33.6 |

Daily impact

The sample in this study was found to miss an average of 23.5% (14.1 days of previous three months; SD=26.00 days) of their productive time in work or school in the past three months because of their migraines. Their productivity at work or school was reduced by half or more in an additional 29.5% (17.7 days; SD=23.81 days) in the past three months. They reported missing an average of 15.4 (SD=20.75) family, social, or leisure, activities over the past three months due to their headaches. Additional information relating to work and activity impairment due to migraine can be found in Table 13.

Table 13.

Activity impairment.

| Mean | SD | % of Days Impacted | |

|---|---|---|---|

| On how many days in the last 3 months did you miss work or school because of your headaches? | 14.1 | 26.00 | 23.5 |

| How many days in the last 3 months was your productivity at work or school reduced by half or more because of your headaches? (Do not include days you counted in the previous question where you missed work or school entirely.) | 17.7 | 23.81 | 29.5 |

| On how many days in the last 3 months did you not do household work (such as housework, home repairs and maintenance, shopping, caring for children and relatives) because of your headaches? | 24.2 | 22.77 | 26.9 |

| How many days in the last 3 months was your productivity in household work reduced by half of more because of your headaches? (Do not include days you counted in the previous question where you did not do household work.) | 21.1 | 21.28 | 23.4 |

| On how many days in the last 3 months did you miss family, social or leisure activities because of your headaches? | 15.4 | 20.75 | 17.1 |

| How many times in the past year would you estimate that you have been to see your physician (not counting any emergency room visits) regarding your headache/migraine? | 3.8 | 1.47 |

Discussion

The present study characterized the treatment patterns, stress characteristics, disorder characteristics and disability profile, of the chronic migraine population. The sample of this study was predominantly female, however, this is similar to other studies which have found that migraine, and chronic migraine in particular, are much more prevalent in the female population [21]. The sample in the study was demographically similar in age to other cross sectional studies of chronic migraineurs [16]. Similar to previous findings, chronic migraines were found to impart significant financial, medical, and social costs, on individuals.

Chronic migraineurs were found to experience a high degree of disability related to their condition and a low level of satisfaction with regard to their medical and therapeutic approaches despite typically being satisfied with their treating physician. This is significant in suggesting that while chronic migraineurs have typically tried multiple treatments without improvement, they are typically still engaged seeking treatment and have generally not resorted to self-medication. Future research should explore the factors that contribute to the resiliency of chronic migraineurs in the context of high medical disability and chronic pain.

Despite being a cross-sectional study, the data presented in this article suggests that chronic migraine should not be viewed as simply a progression from episodic migraine based on easily quantified factors, such as comorbid medical or psychiatric factors. Previous research has identified depression as a causal factor in the progression of episodic migraine to chronic migraine [11]. The sample in this study had been diagnosed with depression at a lower rate than would have been expected if depression was truly a principal precipitating factor in the chronification of migraine. Similarly, chronic medication overuse has been implicated as a causal factor in the chronification of migraine but the sample in this study was found to be both knowledgeable and cautious in their use of abortive migraine medication. It is possible that the participants in this study were made aware of the dangers of medication overuse only after the development of chronic migraine; providers should emphasize the dangers of medication overuse in the context of the chronification of migraine whenever treating patients with episodic migraine. Additionally, a high proportion of the participants in this study who reported a symptom decrease were ignorant of the cause of the reduction in symptoms, attesting to the heterogeneity of the disorder.

An interesting pattern emerged when migraine symptoms were examined by time of day with many participants endorsing the period between 4:00 am–8:00 am as the period they were most likely to experience the signs of an impending migraine attack. This suggests that the sleep/wake cycle of a migraineur may be clinically significant in the chronification of migraine, however, it may also be that these chronic migraineurs have been misdiagnosed and are instead experiencing hypoxic migraines resulting from undiagnosed or untreated sleep apnea.

Similar to previous findings, the chronic migraineurs in this study endorsed a high degree of negative life events resulting from their migraine with the majority of negative events being experienced as social impairments [22,23]. Significantly, the Negative Life Events Score was found to be highly correlated with a large variety of comorbid disorders but was not significantly correlated with the length of time since first migraine symptoms or the length of time since migraine diagnosis. This suggests that chronic migraine is not a static linear progression from episodic migraine and that it is possible that participants in this sample may attribute impairments due to other comorbid psychiatric and medical disorders to their migraine. In light of the finding that the most common comorbid disorders in this sample could be somaticized psychiatric disorders (i.e. depression and anxiety), it is possible that more serious symptoms of psychiatric disorders are being masked by overlapping migraine symptoms, leading to an underestimate of true psychiatric impairment. Further, the sample in this study utilized mental health services in a far lower degree than would have been expected given their reported psychiatric comorbidities. The sample in this study also reported missing a large number of days of professional, educational, and leisure activities in the previous three months due to their migraine. If even a portion of these days can be attributed to psychological symptoms instead of pure migraine symptoms then it is likely that these participants could be experiencing the symptoms of major mental illness, such as major depressive disorder, further emphasizing the need for psychological intervention.

Limitations

There are some limitations to the present study. Participants were recruited through an online portal so issues such as self-identification and self-selection cannot be discounted, however, this is common in migraine literature where surveys are the most prevalent method [17]. As discussed previously, the gender composition of this sample was slightly more female than samples in other large chronic migraine samples [19]. The lack of information collected relating to participant race, education, or socioeconomic status may also limit the generalizability of this study.

Conclusion

The present study extends the literature characterizing the treatment patterns, stress characteristics, disorder characteristics and disability profile, of the chronic migraine population in the largest sample yet collected. Chronic migraineurs were found to experience significant impairment to their personal, professional, and social functioning. Psychological comorbidities were suggested to exert a magnifying effect on the negative experiences of migraine headache with a corresponding underutilization of mental health interventions in this sample. Chronic migraineurs were found to have tried many different treatments but are, overall, unsatisfied with their efficacy while simultaneously being satisfied with their treatment provider. Future research should explore the role of psychiatric distress and somatization as a causal factor in the chronification of migraine. Current providers of chronic migraineurs should emphasize the importance of psychological care in the context of a chronic illness to both address the common psychological component as well as to potentially lessen the impact of chronic migraine on daily life.

Table 9.

Medication and illicit substance use.

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| How quickly do you initiate abortive treatment to stop and/or to treat symptoms? | ||

| Immediately | 2046 | 48.2 |

| Within one hour | 1368 | 32.2 |

| One to two hours | 410 | 9.7 |

| Two to four hours | 157 | 3.7 |

| More than four hours | 37 | 0.9 |

| N/A | 227 | 5.3 |

| Reasons not treated immediately | ||

| I need to make sure it is really a migraine | 899 | 18.8 |

| Don’t want to waste medication | 1086 | 22.7 |

| I get a lot of false alarms | 114 | 2.4 |

| I don’t want to overuse medications | 1239 | 25.9 |

| Other | 330 | 6.9 |

| Illicit Treatments | ||

| Used a drug that was not prescribed to treat migraine | 1056 | 26.1 |

| Ever used illicit drug to treat migraine | 385 | 9.5 |

| Used marijuana | 806 | 19.9 |

| Used alcohol to treat migraine | 289 | 7.1 |

| Used nicotine/tobacco to treat migraine | 189 | 4.7 |

| Ever avoided a medication because of side effects | 2699 | 66.8 |

| Ever stopped a medication due to side effects | 3034 | 75.1 |

| Stopped due to: | ||

| nausea/vomiting | 1075 | 22.5 |

| stomach ache | 600 | 12.5 |

| rebound headaches | 1378 | 28.8 |

| dizziness | 966 | 20.2 |

| cognitive challenges | 1677 | 35.0 |

| other reason | 1687 | 35.2 |

| Avoided medicine due to cost | 1961 | 48.9 |

| Withheld medication because you wanted to “spare” or “save” medication | 3055 | 76.1 |

| How many different prescription products do you currently use to treat migraine | ||

| 0 | 295 | 7.4 |

| 1 | 662 | 16.6 |

| 2 | 969 | 24.3 |

| 3 | 839 | 21.1 |

| 4 or more | 1215 | 30.5 |

| How many (if any) prescription products have you EVER USED to TREAT your migraines? By “ever used” we mean that you have ever taken at any point to treat your migraines. | ||

| 0 | 23 | 0.6 |

| 1 | 108 | 2.7 |

| 2 | 289 | 7.3 |

| 3 | 415 | 10.4 |

| 4 | 412 | 10.4 |

| 5 | 311 | 7.8 |

| 6 or more | 2422 | 60.9 |

| How much would you estimate that you pay out of pocket monthly for medications and care related to your migraines, including insurance co-pays? | ||

| 0–100 | 1824 | 45.5 |

| 101–250 | 1135 | 28.3 |

| 251–500 | 469 | 11.7 |

| >500 | 288 | 7.2 |

| not sure | 297 | 7.4 |

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was partially provided by the National Institutes of Health. Grant no: K23DA030397 (awarded to AW).

References

- 1.Smitherman TA, Burch R, Sheikh H, Loder E. The prevalence, impact, and treatment of migraine and severe headaches in the United States: a review of statistics from national surveillance studies. Headache. 2013;53:427–436. doi: 10.1111/head.12074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vargas BB, Dodick DW. The face of chronic migraine: epidemiology, demographics, and treatment strategies. Neurol Clin. 2009;27:467–479. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bigal ME, Rapoport AM, Lipton RB, Tepper SJ, Sheftell FD. Assessment of migraine disability using the migraine disability assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire: a comparison of chronic migraine with episodic migraine. Headache. 2003;43:336–342. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2003.03068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katsarava Z, Buse DC, Manack AN, Lipton RB. Defining the differences between episodic migraine and chronic migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2012;16:86–92. doi: 10.1007/s11916-011-0233-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manack AN, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Chronic migraine: epidemiology and disease burden. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2011;15:70–78. doi: 10.1007/s11916-010-0157-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stewart WF, Wood GC, Manack A, Varon SF, Buse DC, et al. Employment and work impact of chronic migraine and episodic migraine. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52:8–14. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181c1dc56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aurora SK. Spectrum of illness: understanding biological patterns and relationships in chronic migraine. Neurology. 2009;72:S8–13. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31819749fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aurora SK, Barrodale P, Chronicle EP, Mulleners WM. Cortical inhibition is reduced in chronic and episodic migraine and demonstrates a spectrum of illness. Headache. 2005;45:546–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peres MF, Sanchez del Rio M, Seabra ML, Tufik S, Abucham J, et al. Hypothalamic involvement in chronic migraine. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:747–751. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.71.6.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Obermann M, Gizewski ER, Limmroth V, Diener HC, Katsarava Z. Symptomatic migraine and pontine vascular malformation: evidence for a key role of the brainstem in the pathophysiology of chronic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2006;26:763–766. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashina S, Serrano D, Lipton RB, Maizels M, Manack AN, et al. Depression and risk of transformation of episodic to chronic migraine. J Headache Pain. 2012;13:615–624. doi: 10.1007/s10194-012-0479-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D’Amico D, Grazzi L, Usai S, Rigamonti A, Curone M, et al. Disability pattern in chronic migraine with medication overuse: a comparison with migraine without aura. Headache. 2005;45:553–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.http://ihs-classification.org/en/02_klassifikation/02_teil1/01.05.01_migraine.html.

- 14.Cernuda-Morollón E, Larrosa D, Ramón C, Vega J, Martínez-Camblor P, et al. Interictal increase of CGRP levels in peripheral blood as a biomarker for chronic migraine. Neurology. 2013;81:1191–1196. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a6cb72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cupini LM, Costa C, Sarchielli P, Bari M, Battista N, et al. Degradation of endocannabinoids in chronic migraine and medication overuse headache. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;30:186–189. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buse DC, Manack A, Serrano D, Turkel C, Lipton RB. Sociodemographic and comorbidity profiles of chronic migraine and episodic migraine sufferers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:428–432. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.192492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bigal ME, Serrano D, Reed M, Lipton RB. Chronic migraine in the population: burden, diagnosis, and satisfaction with treatment. Neurology. 2008;71:559–566. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000323925.29520.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bigal ME, Borucho S, Serrano D, Lipton RB. The acute treatment of episodic and chronic migraine in the USA. Cephalalgia. 2009;29:891–897. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buse DC, Manack AN, Fanning KM, Serrano D, Reed ML, et al. Chronic migraine prevalence, disability, and sociodemographic factors: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Study. Headache. 2012;52:1456–1470. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2012.02223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lipton RB1. Tracing transformation: chronic migraine classification, progression, and epidemiology. Neurology. 2009;72:S3–7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181974b19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buse DC, Manack AN, Fanning KM, Serrano D, Reed ML, et al. Chronic migraine prevalence, disability, and sociodemographic factors: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Study. Headache. 2012;52:1456–1470. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2012.02223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malone CD, Bhowmick A, Wachholtz AB. Migraine: treatments, comorbidities, and quality of life, in the USA. J Pain Res. 2015;8:537–547. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S88207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.http://migraine.com.