Abstract

BACKGROUND

Testing, refining, and tailoring theoretical approaches that are hypothesized to reduce sexual risk behaviors among adolescent subpopulations is an important task. Relatively little is known about the relationship between components of the information-motivation-behavior (IMB) model and sexual behaviors among underage minority youth. Using the IMB model, this study examines predictors of risky sexual behavior among underserved Hispanic and African-American youth.

METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted with a sample of 380 youths aged 11–17 years recruited in Los Angeles, California, and utilized latent variable models to examine interrelationships and predictive relations among IMB model variables associated with risky sexual behavior.

RESULTS

Sixty percent of the participants aged 15–17 and 1 out of 10 participants aged 11–12 reported prior sexual intercourse. Of the sexually active, more than half reported having unprotected sex and 11% had sexual intercourse with 4 or more partners. Results of the structural equation model indicated that older age and attitudes against sexual activities had significant, direct impacts on risky sexual behaviors. Behavioral refusal skills, positioned as an intervening variable, also significantly predicted less risky sex. Knowledge, attitudes against sexual activities, and perceived peer pressure against sexual behavior predicted sexual refusal skills. Additionally, there were significant indirect effects on risky sexual behavior mediated through behavioral refusal skills.

CONCLUSION

A large number of disadvantaged minority urban youth are engaged in risky sexual behaviors. Intervention programs, particularly those targeting preadolescents, should focus on building long-lasting behavioral skills that emphasize the reduction of peer pressure and normative influences on risky sexual behaviors. Components of the IMB model clearly have a role in the design of efficacious interventions.

Keywords: information-motivation-behavior model, minority youth, urban youth, preadolescents, sexual behavior

The human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) epidemic in the United States has stimulated considerable research on sexual behaviors as well as prevention efforts that focus specifically on adolescents and younger adults. Meta-analyses of these interventional studies show that the most effective interventions were those that have been constructed and implemented using a specific theoretical framework1–3 that contained attitudinal components, educational information, as well as behavioral skills training.1 Another particularly important point emerging from these meta-analytic reviews was that adolescents are a heterogeneous mosaic of subgroups consisting of different ethnicities/cultures, behavioral risk characteristics, and developmental levels. Furthermore, because of manifold differences between adolescent subgroups, developing interventions specifically for well-defined targeted subgroups of adolescents has been found to produce superior results in terms of reducing risky sexual behaviors.1,2 Therefore, the testing, retesting, and modification of the theoretical framework designed to explain and reduce the sexual risk-taking behaviors among adolescent subpopulations remain important tasks. Exploration of the unique application of these models to specific adolescent subgroups, particularly at-risk underserved minority populations, will ultimately lead to a more focused understanding of the unique risk factors facing these groups, as well as contribute to the development of more powerful tools and more effective interventions with these specific populations.

Reviews of recent theoretical-based interventions for reducing risky sexual behaviors reveal that the information-motivation-behavior (IMB) model3,4 has been widely used and shown to be an effective theoretical foundation for modifying risky sexual behavior among multiple populations. Some examples include college students in general,3,5 female college students in particular,6,7 Latina college students,8 women in low-income housing,9 intravenous drug users,10 truck drivers,11 male and female sexually trasmitted infected patients,12 HIV-infected patients,13 and HIV-positive men who have sex with men.14 Additionally, the IMB model has also been found to explain a significant portion of the variance of sexual behavior among sexually active “mostly minority” older adolescents15 as well as condom use among juvenile offenders.13 However, little is known about the relationship between the IMB components and sexual behaviors among minority youth, especially underage youth.

The present study employed the IMB theoretical framework and structural equation modeling (SEM) in order to examine relations among risky sexual behavior; information (knowledge about sexually trasmitted infections [STIs]/HIV and pregnancy); motivation (perceived pregnancy repercussions, attitudes against sexual activities); beliefs (perceived peer pressure about sexual behavior); and sexual behavior refusal skills among underserved African-American and Hispanic youth aged 11–17 years attending after-school clubs in Los Angeles, California. The significance of this study is 3-fold. First, it includes pre- and early adolescent individuals (ages 11–12 years) who have been largely excluded from research on sexual activities among youth. Many factors that affect sexual behavior, particularly sexual norms and attitudes, may be shaped and developed before youth reach their teen years.16 Additionally, despite the fact that a substantial proportion of minority boys and a slightly smaller proportion of girls report that their first sexual intercourse occurred before age 15, data on sexual behavior and its correlates are especially scarce among these preadolescent youth.17 Second, this research includes data on both African-American and Hispanic youth, recruited from 1 of the most underserved and impoverished areas in the nation.18,19 These youth are among those most at risk for the consequences of early adolescent sexuality, including sexually transmitted diseases, adolescent pregnancy, and secondary deleterious effects of early sexual activity including decreased academic attainment and other maladaptive outcomes. The results of this evaluation of the utility of the IMB model in explaining the determinants of sexual behavior among these minority youth may provide direction for future modifications of IMB-based interventions for this at-risk population.

Theoretical Framework

The IMB theoretical framework was developed by Fisher and colleagues3,4 and has been validated extensively in over a decade of correlational and experimental research concerning HIV-related behaviors.20 This model posits that sexual behavior is a function of the individual’s information about STIs, pregnancy-related knowledge, attitude and motivation toward sexual activity, and, subsequently, the behavioral skills essential to refuse sexual intercourse effectively, while minimizing the negative consequences that may come with this refusal. On the basis of this reasoning from the IMB model, information on how STIs are transmitted and the social, economic, and psychological consequences of teen pregnancy are prerequisites for informed discussions about sexual activities.3,21 However, information by itself has not been found to be sufficient in promoting decreased risky sexual behaviors. Assessing a person’s level of knowledge provides only a partial picture of how behavior is influenced.21–23 Highly informed individuals may have high or low motivation to remain sexually inactive while highly motivated individuals may or may not be highly informed. Therefore, conceptually, information and motivation both are thought to influence the use of behavioral skills to engage in or prevent sexual behavior in quite different ways.21

According to the IMB model, behavioral skills refer to the possession of the requisite skills to avoid sexual intercourse (eg, to be able to determine what situations to avoid, how to reject sexual intercourse effectively without losing a friend, etc).4 The model further assumes that factors such as perceived costs and benefits of risky sexual behaviors may also affect motivation to engage in a given activity. Clearly, in developing an effective intervention, it is vital to determine and fully identify the behaviors targeted for change. The IMB model views health-behavior modification as a process of providing relevant detailed information while understanding cultural practices and norms in order to carefully create an atmosphere conducive to the consideration of an alternative practice. Enhancing the motivation for the modification of behavior and providing culturally acceptable skills will ultimately lead to promoting alternative behaviors.3,4

In this study, we test a predictive theoretical model using constructs from the IMB model enhanced with key demographic variables of age, gender, and ethnicity. Developmentally, we expect that the older youth will have engaged in more sexual behaviors. We also expect that females will be more negative or concerned about the repercussions from pregnancy and feel more pressure to refrain from sexual activity. We position information and motivational components of the model as proximal predictors of sexual behavior refusal skills. In turn, we position the outcome of risky sexual behavior as initially predicted by lower refusal skills. However, we also assess whether any of the background demographics or intervening information or motivation constructs predict risky sexual behavior directly or rather if it is mediated through refusal skills.

METHODS

Participants

This cross-sectional study was performed with a nonprobability original sample of 416 youth recruited from 11 after-school club sites and charter schools that serve more than 1400 predominantly minority students, located in South Los Angeles, California. This study used only the ethnic minority youth under the age of 18 in the sample leaving a total of 380 Hispanic (N = 86) and African-American (N = 294) youth. The sample was 49.6% male (N = 184), and 50.4% female (N = 196). Their ages ranged from 11 to 17 years (mean age = 13.5 years). Approximately 37% of the population in this portion of Los Angeles live below the federal poverty level.18 According to the 2002–2003 Los Angeles County Health Survey, the public high school dropout rate in this portion of Los Angeles is 27.4%.19 Table 1 reports demographic and other information about the 380 participants.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Sexual Behaviors of Sample (n = 380)

| Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | 13.5 ± 1.6 |

| 11–12 | 115 (30.3) |

| 13–14 | 174 (45.8) |

| 15–17 | 91 (23.9) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 184 (48.4) |

| Female | 196 (51.6) |

| Ethnicity | |

| African American | 294 (77.4) |

| Hispanic | 86 (22.6) |

| Ever had sexual intercourse without using condoms | |

| Never had sexual intercourse | 271 (71.3) |

| No | 52 (13.7) |

| Yes | 57 (15.0) |

| Number of sexual partners (lifetime) | |

| None | 271 (71.3) |

| One person | 34 (9.0) |

| Two persons | 24 (6.3) |

| Three persons | 15 (4.0) |

| Four or more persons | 36 (9.4) |

| Age at first sexual intercourse | |

| 11–12 | 48 (12.6) |

| 13–14 | 45 (11.8) |

| 15–17 | 16 (4.2) |

| No experience | 271 (71.3) |

After obtaining permission from the club directors and school principals, we notified parents/guardians and provided an opportunity for them to exclude their child from participation in the intervention and survey. Less than 3% of parents/guardians refused to allow their children to participate in the program activities. We also asked students to assent to participate in the study. No monitory or other type of incentive for participation in the program was provided. The survey procedures were designed to protect participant privacy and allow for anonymous participation. This survey was self-administered in the absence of the instructor and collected by research associates of this project who were unaffiliated with the after-school clubs and schools. Participants were given a brief introduction and were asked not to write their name or any other identifiable information anywhere on the survey. This survey was administered before an educational motivational intervention was implemented to reduce risk-taking behaviors among high-risk youth in South Los Angeles.

Measures

The survey was adapted from a similar study among Hispanic and African-American adolescents23 and the National Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) conducted by the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.24 In the model tested in this study, single-item demographic variables were included as background predictors and all IMB constructs and the outcome measure were represented as latent variables.

Demographics

Single-item demographic information represented in the model included age in years, gender (male = 1, female = 2), and ethnicity (1 = African American, 2 = Hispanic).

Knowledge

Eight items assessed students’ knowledge about STIs/HIV and pregnancy. Appropriate test-retest reliability measures were documented by repeating the survey within 1 week with 18 students (the Spearman rank correlation coefficient = .85). These 18 students were randomly selected from a class in 1 of the club sites; however, the data from these participants were not included in our data analysis. The Knowledge latent variable was indicated by 1 item that reflected their score on pregnancy knowledge, and 1 item reflecting their score on STI/HIV knowledge. The 2 items had a reliability coefficient of .50.

The Negative Pregnancy Repercussions

This latent variable was indicated by 4 items that ranged from 1 to 3 (coefficient α = .73). Typical items included “If I get pregnant (girls) or if I get someone pregnant (boys), it would be difficult for me to finish high school,” and “if I get pregnant (girls) or if I get someone pregnant (boys), my family members will lose respect for me.”

Attitudes Against Sexual Activities

This latent variable was indicated by 3 mean composites created from 9 attitudinal items that ranged from 1 to 3. The parcels were created to avoid too many indicators based on the sample size. Typical items included “teens who don’t have sex are cool” and “it’s inappropriate for me to have sex” (coefficient α = .66).

Perceived Peer Pressure

Perceived peer pressure was indicated by 4 mean composites created from 8 items scaled 1 to 3. Typical items included “I’m encouraged by my friends to not have sex” and “I would fit in with my friends if I do not have sex” (coefficient α = .53).

Sexual Behavior Refusal Skills

Sexual behavior refusal skills were indicated by 4 items scaled 1 to 3 (coefficient α = .59). (1) I am able to resist and control sexual urges; (2) I can have a boyfriend/girlfriend without having sex; (3) I can say no if my boy friend/girlfriend pressures me to have sex; (4) I know how to avoid situations that put me at risk of sexual advances.

Risky Sexual Behavior

Risky sexual behavior was indicated by 3 items (coefficient α = .93). (1) Whether they ever had sex without condoms which was scored 0–2 (never had sex = 0, no = 1, yes = 2); (2) how many sexual partners they had had during their lifetime (range = 0–6); and (3) an indicator based on their age of first sexual intercourse. Higher scores reflected earlier sexual experience (0 = none; 1 = 17 years at first experience, 2 = age 15 or 16 years; 3 = age 13 or 14 years; 4 = age 12 or younger).

Analysis

The latent variable analyses were performed using the structural equation modeling software (EQS) program. Latent variables are hypothesized underlying constructs that explain the shared variance among indicator variables. Owing to multivariate kurtosis, goodness of fit of the models was assessed with the Robust Satorra-Bentler chi-square statistic in addition to the maximum-likelihood chi-square statistic, the comparative fit index (CFI), the robust comparative fit index (RCFI), and the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA). The CFI and RCFI range from 0 to 1 and reflect the improvement in fit of a hypothesized model over a model of complete independence among the measured variables. CFI and RCFI values approaching .95 or greater are desirable, indicating that the hypothesized model reproduces 95% or more of the covariation in the data. The RMSEA is a measure of lack of fit per degrees of freedom; values less than .06 indicate a good fit between the hypothesized model and the observed data.

An initial confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) assessed the adequacy of the measurement model and provided the relations among the demographic variables and the latent variables. To improve fit, if necessary, we planned to add a minimal number of correlated error residuals suggested by the lagrange multiplier (LM) test provided the correlated error residuals were plausible and logical. Subsequently, a predictive theoretical model positioned the demographic variables as predictors of the components of the IMB model: knowledge, and the motivational and attitudinal factors of negative pregnancy repercussions, Attitudes against sexual activities, and perceived peer pressure. In turn, these model constructs predicted sexual behavior refusal skills. The latent variable representing sexual behavior refusal skills was positioned as the predictor of risky sexual behavior. Suggestions from the LM test were added to this model to determine whether any of the demographic variables or information-motivation-attitude variables had significant direct effects on risky sexual behavior. Non-significant paths and correlations among the predictors were gradually dropped until only significant paths remained. Indirect effects mediated through intervening variables were also assessed.

RESULTS

Sexual Activity

Concerning their sexual activities, about 71% of the participants sampled claimed that they had not previously engaged in sexual intercourse (see Table 1). When prior experience with intercourse was examined among the youth, the youngest adolescent age group (ages 11–12) had a markedly lower likelihood of having previously engaged in sexual intercourse than the oldest adolescent age group (ages 15–17). Ten percent of participants aged 11–12 years reported that they had had sexual intercourse whereas 25% and 60% of the 13–14- and 15–17-year-old participants indicated previously having intercourse, respectively. Of participants who had engaged in sexual intercourse, 54% indicated that at least 1 of their sexual intercourse encounters was performed without the use of condom. Nearly 10% of this sample admitted that they had sexual intercourse with 4 or more partners. In addition, 15% of sexually active adolescent participants (5% of total sample) reported that they had been diagnosed with 1 or more sexually transmitted diseases.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

After very minimal model modification, the CFA had an acceptable fit for both the ML and robust solutions (ML χ2(N = 380) = 340.26, 194 df; CFI = .94, RMSEA = .045. S-B χ2 = 313.53, 194 df; RCFI = .95, RMSEA = .040). All hypothesized factor loadings were significant (p < .001). Only 3 correlated error residuals were added to the model. Table 2 presents the summary statistics and factor loadings in the CFA model. Table 3 reports the associations among the demographics and constructs in the IMB model. Older participants had greater knowledge about pregnancy and STIs (r = .43, p < .001) and were less inclined to hold negative views about pregnancy repercussions (−.21, p < .001), sexual activities (−.23, p < .001), and peer pressure (−.24, p < .001). They were more likely to report risky sexual behavior (.48, p < .001). Females held negative views about pregnancy repercussions (.25, p < .001), were more likely to have attitudes against sexual activities (.49, p < .001), to report more peer pressure (.38, p < .001), reported better refusal skills (.21, p < .001), and reported less risky sexual behavior (−.30, p < .001). Ethnicity only exerted minor influences in the model. Hispanics reported lower attitudes against sexual activities (−.18, p < .001). Knowledge was significant associated with refusal skills (.34, p < .001). The motivational latent variables of negative pregnancy repercussions, attitudes against sexual activities, perceived peer pressure, and the behavioral variable of refusal skills were substantially and significantly associated among themselves and were all negatively associated with risky sexual behavior (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary Statistics and Factor Loadings in the CFA Model

| Variables | Mean (SD) (%) | Factor Loading | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | |||

| Pregnancy knowledge | 1.6 | 1.3 | .43 |

| Knowledge STD/HIV | 2.3 | 1.2 | .79 |

| Negative pregnancy repercussions | |||

| Hard to finish high school | 2.5 | 0.8 | .42 |

| Hard to go to college | 2.5 | 0.8 | .47 |

| My friends lose respect for me | 1.9 | 0.8 | .80 |

| Family member lose respect for me | 1.9 | 0.8 | .78 |

| Attitudes against sexual activities | |||

| Attitudes 1 | 2.2 | 0.6 | .56 |

| Attitudes 2 | 2.1 | 0.6 | .68 |

| Attitudes 3 | 2.2 | 0.5 | .65 |

| Perceived peer pressure | |||

| Peer pressure 1 | 2.4 | 0.6 | .57 |

| Peer pressure 2 | 2.4 | 0.6 | .64 |

| Peer pressure 3 | 2.4 | 0.6 | .25 |

| Peer pressure 4 | 2.7 | 0.5 | .28 |

| Sexual behavior refusal skills | |||

| I can resist sexual urges | 2.5 | 0.7 | .49 |

| I can have a boyfriend/girlfriend without having sex | 2.8 | 0.6 | .54 |

| I can say no if pressured to have sex | 2.6 | 0.6 | .45 |

| I can avoid situations that put me at risk of having sex | 2.6 | 0.6 | .54 |

| Risky sexual behavior | |||

| Number of sex partners | 0.8 | 1.7 | .83 |

| Sex without condom | 0.4 | 0.7 | .96 |

| Early sexual activities | 0.9 | 1.5 | .92 |

All factor loadings significant, p ≤ .001.

Table 3.

Correlations Among Demographic and Latent Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | — | ||||||||

| 2. Female | −.11* | — | |||||||

| 3. Hispanic | −.06 | .02 | — | ||||||

| 4. Knowledge | .43*** | .08 | −.12 | — | |||||

| 5. Negative pregnancy repercussions | −.21*** | .25*** | .08 | .06 | — | ||||

| 6. Attitude against sexual activities | −.23*** | .49*** | −.18*** | .14 | .41*** | — | |||

| 7. Perceived peer pressure | −.24*** | .38*** | .03 | .08 | .25*** | .65*** | — | ||

| 8. Refusal skills | −.09 | .21*** | −.12 | .34*** | .19** | .55*** | .73*** | — | |

| 9. Risky sexual behavior | .48*** | −.30*** | −.02 | .07 | −.30*** | −.51*** | −.44*** | −.38*** | — |

p < .05

p < .001

p < .001.

Path Analysis

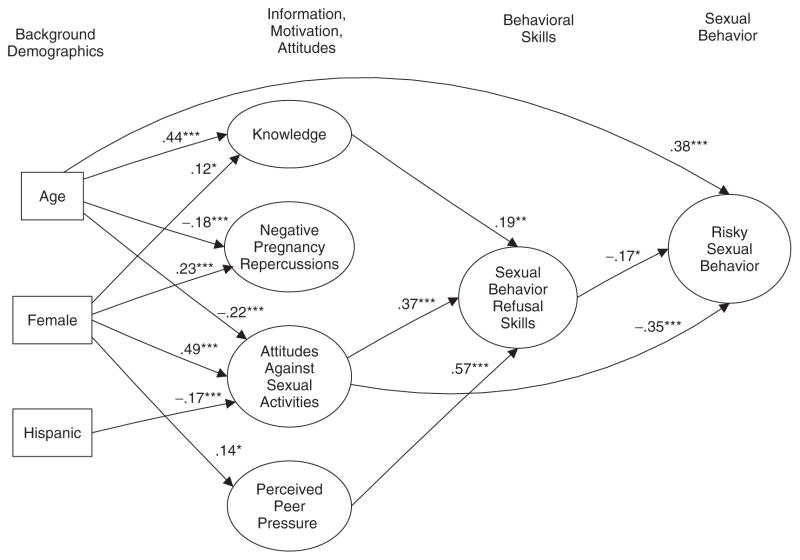

A latent variable path analysis tested the predictive utility of the hypothesized IMB model. Figure 1 depicts the final model after nonsignificant paths were trimmed, and additional paths were added based on suggestions from the LM test. Fit indices for this model are acceptable (ML χ2(N = 380) = 353.76, 211 df; CFI = .94, RMSEA = .042. S-B χ2 = 28.44, 211 df; RCFI = .95, RMSEA = .038). The IMB model predicted 43% of the variance for risky sexual behavior and 64% of the variance in refusal skills.

Figure 1.

Path Model Depicting Significant IMB Model Predictors of Risky Sexual Behavior Among Minority Adolescents (N = 380), *p < .05, **p < .001, ***p < .001

Direct Effects

Risky sexual behavior was predicted by lower sexual behavior refusal skills (standardized regression coefficient = −.17, p < .05), older age (.38, p < .001), and lower attitudes against sexual activities (−.35, p < .001). Sexual behavior refusal skills were significantly predicted by IMB model components of knowledge (.19, p < .01), attitudes against sexual activities (.37, p < .001), and perceived peer pressure (.57, p < .001). Female gender predicted more knowledge (.12, p < .05), higher negative pregnancy repercussions (.23, p < .001), positive attitudes against sexual activities (.49, p < .001), and more perceived peer pressure (.14, p < .05). Hispanic ethnicity predicted lower attitudes against sexual activities (−.17, p < .001). Older participants reported more knowledge (.44, p < .001), lower negative pregnancy repercussions (−.18 p < .001), and lower attitudes against sexual activities (−.22, p < .001).

Significant indirect effects on risky sexual behavior include lower attitudes against sexual activities (p < .05), less perceived peer pressure (p < .05), age (p < .01), a negative indirect effect of female gender (p < .001), and a positive effect of Hispanic ethnicity (p < .001). The indirect effect of knowledge was not significant. The demographic variables of female gender (p < .001) and Hispanic ethnicity (p < .01) exerted significant indirect effects on sexual behavior refusal skills as well.

DISCUSSION

Using the IMB model to assess risky sexual behavior was very effective. Our proposed latent variable model accounted for 43% of the variance in risky sexual behavior among underserved African-American and Latino underage youth. In addition, information and motivational components of the model explained 64% of the variance in refusal skills. This finding suggests that components of the IMB model are viable and malleable leverage points to improve skills and attitudes that can decrease high-risk behaviors among youth.

This study documented that minority youth who were equipped with the behavioral skill of self-efficacy to overcome the sociopsychological consequences of refusing to have sex were less likely to engage in risky sexual behaviors. Both perceived peer pressure and attitudes against sexual activities were strongly associated with sexual behavior refusal skills. This finding confirms the IMB model’s central proposition that attitudes and motivation influence behavioral skills which in turn affect sexual behaviors. There is a need for a comprehensive approach for minority youth that influences the attitudes and motivations related to premature and risky sexual behaviors, and emphasizes the development of behavioral skills to negotiate encounters with peers effectively.2,4,23,25

Our data show that when compared with older participants, younger participants were more likely to report lower level of knowledge about STIs/HIV and pregnancy. In addition, older age was associated with less negative attitudes about pregnancy repercussions. It is important to note that more than 41% of sexually active participants indicated that they first had sexual intercourse when they were 11 or 12 years old. Indeed, it has been well documented that preadolescent/early adolescent sexual activity leads to a number of negative health and social outcomes (future depression; suicidal ideation and attempt; future intention to engage in other risk behaviors).26–29 Therefore, sexual interventions should be geared toward preadolescent/early adolescent years when youth sexual peer norms and pressures are being developed.16 Another advantage of conducting an intervention at an earlier age is that it may include students who are otherwise inaccessible at later ages because of higher rates of school dropouts, particularly among minority students in urban areas such as Los Angeles.18,30

In the predictive path model the demographic variables of age, gender, and ethnicity, did not predict behavioral skills although female gender and refusal skills were significantly associated in the bivariate analysis. However, the data documented a significant relationship between the demographic variables and knowledge, attitude, and motivation. Furthermore, the demographics predicted refusal skills indirectly as mediated through information/knowledge, attitudes, and motivations. Additionally, information/knowledge was not directly associated with risky sexual behaviors. These findings support the notion that teaching the fundamentals of HIV, STIs, and pregnancy prevention are not sufficient to alter the risky sexual behaviors of adolescents significantly. Therefore, future intervention designs should be more theoretically based and culturally appropriate, and should equip minority students with a foundation of knowledge and motivation in order to build the necessary behavioral skills with which students from underserved minority populations can make educated decisions in regards to their sexual behavior. These findings point to an urgent need and major effort to design culturally appropriate educational and motivational interventions that reflect the cultural values of youth of different genders and ethnicities.

Limitations

Whereas this study provides important insights into the relationships among attitudes, motivation, behaviors skills, and their influence on risky sexual behaviors among minority youth, its retrospective cross-sectional design limits our ability to delineate conclusively the sequential and causal relationships between variables. However, our design, which is faithfully based on the IMB model, is a logical formulation that well represents the model’s components and hypothetical order wherein attitudes, motivations, and knowledge precede skills which in turn predict behaviors. Furthermore, the sample in this study was selected from high-poverty, underserved minority communities, and does not include those students who have dropped out of school. Additionally, the current study is limited to urban underserved African-American and Latino youth in Los Angeles, California. Thus, our participants may not be representative of African-American and Latino adolescents from other geographic areas or socioeconomic strata.

Conclusions

The IMB was a useful theory in explaining risky sexual behaviors within an underage sample of minority youth. This type of sample is relatively rare in terms of assessing specific sexual behaviors, so these findings are quite important in suggesting directions for future research as well as topics to be addressed in intervention programs. The specific items in the analysis provide a useful framework for effective curriculum development. For example, refusal skills and attitudes against sexual activities directly predicted less risky sexual behavior. Furthermore, refusal skills were impacted by peer pressure, knowledge, and attitudes against sexual activities. Developing an effective refusal skill curriculum would be an important step in curtailing high-risk behaviors in young people.

IMPLICATIONS FOR SCHOOLS

As mentioned above, youth as young as 11 years of age reported engaging in sexual behaviors including intercourse although in general older youth were more likely to engage in such behaviors as would be expected developmentally. In addition, knowledge alone did not predict less sexual risk behavior. The most salient constructs within the IMB model were refusal skills (behaviors) and attitudes against sexual activities (motivations). Although the schools are expected to serve numerous roles for young people in our society, age-appropriate sex education may need to be enhanced to provide opportunities for children and adolescents to learn and practice refusal skills within the context of the classroom. As previously mentioned, minority youth tend to have high dropout rates, so these interventions may need to be implemented when they are relatively young, such as in grades 6–8, rather than waiting until they are in high school. Furthermore, the females were considerably more concerned about pregnancy repercussions than the males. Young males need to develop more awareness of the difficulties and negative ramifications of teen pregnancy both for individuals and for society.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Mohsen Bazargan received support from the UCLA/DREW Project EXPORT, NCMHD, 2P20MD000182. Additionally, Dr. Judith A. Stein received support from NIDA grant DA 01070-36.

Footnotes

Human Subjects Approval Statement. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Charles Drew University of Medicine and Science.

Contributor Information

Mohsen Bazargan, Email: mobazarg@cdrewu.edu.

Judith A. Stein, Email: jastein@ucla.edu.

Shahrzad Bazargan-Hejazi, Email: shbazarg@cdrewu.edu.

David W. Hindman, Email: davidhindman@cdrewu.edu.

References

- 1.Albarracin D, Gillette JC, Earl AN, Glasman LR, Durantini MR, Ho MH. A test of major assumptions about behavior change: a comprehensive look at the effects of passive and active HIV-prevention interventions since the beginning of the epidemic. Psychol Bull. 2005;131(6):856–897. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sales JM, Milhausen RR, Diclemente RJ. A decade in review: Building on the experiences of past adolescent STI/HIV interventions to optimise future prevention efforts. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(6):431–436. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.018002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Misovich SJ, Kimble DL, Malloy TE. Changing AIDS risk behavior: effects of an intervention emphasizing AIDS risk reduction information, motivation, and behavioral skills in a college student population. Health Psychol. 1996;15(2):114–123. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.2.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Bryan AD, Misovich SJ. Information-motivation-behavioral skills model-based HIV risk behavior change intervention for inner-city high school youth. Health Psychol. 2002;21(2):177–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kiene SM, Barta WD. A brief individualized computer-delivered sexual risk reduction intervention increases HIV/AIDS preventive behavior. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(3):404–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaworski BC, Carey MP. Effects of a brief, theory-based STD-prevention program for female college students. J Adolesc Health. 2001;29(6):417–425. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00271-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh S. Study of the effect of information, motivation and behavioural skills (IMB) intervention in changing AIDS risk behaviour in female university students. AIDS Care. 2003;15(1):71–76. doi: 10.1080/095401202100039770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones SG, Patsdaughter CA, Jorda MLM, Hamilton MD, Malow R. SENORITAS: an HIV/sexually transmitted infection prevention project for Latina college students at a Hispanic-serving university. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2008;19(4):311–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson ES, Wagstaff DA, Heckman TG, et al. Information-motivation-behavioral skills (IMB) model: testing direct and mediated treatment effects on condom use among women in low-income housing. Ann Behav Med. 2006;31(1):70–79. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3101_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Copenhaver MM, Lee IC. Optimizing a community-friendly HIV risk reduction intervention for injection drug users in treatment: a structural equation modeling approach. J Urban Health. 2006;83(6):1132–1142. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9090-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cornman DH, Schmiege SJ, Bryan A, Benziger TJ, Fisher JD. An information-motivation-behavioral skills (IMB) model-based HIV prevention intervention for truck drivers in India. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(8):1572–1584. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalichman SC, Cain D, Weinhardt L, et al. Experimental components analysis of brief theory-based HIV/AIDS risk-reduction counseling for sexually transmitted infection patients. Health Psychol. 2005;24(2):198–208. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robertson AA, Stein JA, Baird-Thomas C. Gender differences in the prediction of condom use among incarcerated juvenile offenders: testing the information-motivation-behavior skills (IMB) model. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(1):18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knauz RO, Safren SA, O’Cleirigh C, et al. Developing an HIV-prevention intervention for HIV-infected men who have sex with men in HIV care: project enhance. Aids Behav. 2007;11(suppl 5):S117–S126. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisher WA, Williams SS, Fisher JD, Malloy TE. Understanding AIDS risk behavior among sexually active urban adolescents: An empirical test of the information-motivation-behavioral skills model. AIDS Behav. 1999;3(1):13–23. [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Donnell L, Myint UA, O’Donnell CR, Stueve A. Long-term influence of sexual norms and attitudes on timing of sexual initiation among urban minority youth. J Sch Health. 2003;73(2):68–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2003.tb03575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Donnell L, Stueve A, Agronick G, Wilson-Simmons R, Duran R, Jeanbaptiste V. Saving sex for later: an evaluation of a parent education intervention. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2005;37(4):166–173. doi: 10.1363/psrh.37.166.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Los Angeles County Department of Health Services. [Accessed March 2010];Key Indicators of Health By Service Planning Area. Available at: http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/ha/docs/2007%20LACHS/KeyIndicator2007/KIR2009FINALr1.pdf.

- 19.Los Angeles County Department of Health Services. [Accessed March 2010];SPA 6—South Area Health Office—Health Assessment Report: SPA 6 Statistics—Executive Summary. Available at: http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/spa6/stats/spa6statsexecutivesummary.htm.

- 20.Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Amico KR, Harman JJ. An information-motivation-behavioral skills model of adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Health Psychol. 2006;25(4):462–473. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Williams SS, Malloy TE. Empirical tests of an information-motivation-behavioral skills model of AIDS-preventive behavior with gay men and heterosexual university students. Health Psychol. 1994;13(3):238–250. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.3.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bazargan M, Kelly EM, Stein JA, Husaini BA, Bazargan SH. Correlates of HIV risk-taking behaviors among African-American college students: the effect of HIV knowledge, motivation, and behavioral skills. J Natl Med Assoc. 2000;92(8):391–404. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bazargan M, West K. Correlates of the intention to remain sexually inactive among underserved Hispanic and African American high school students. J Sch Health. 2006;76(1):25–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2006.00063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (CDC) Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2003. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bralock AR, Koniak-Griffin D. Relationship, power, and other influences on self-protective sexual behaviors of African American female adolescents. Health Care Women Int. 2007;28(3):247–267. doi: 10.1080/07399330601180123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hallfors DD, Waller MW, Bauer D, Ford CA, Halpern CT. Which comes first in adolescence-sex and drugs or depression? Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(3):163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hallfors DD, Waller MW, Ford CA, Halpern CT, Brodish PH, Iritani B. Adolescent depression and suicide risk: association with sex and drug behavior. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(3):224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu S, Deveaux L, Lunn S, et al. At greatest risk: pre- and early adolescent Bahamian youth experiencing anal intercourse. Int J STD AIDS. 2007;18(6):396–401. doi: 10.1258/095646207781024784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lehrer JA, Shrier LA, Gortmaker S, Buka S. Depressive symptoms as a longitudinal predictor of sexual risk behaviors among US middle and high school students. Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):189–200. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dalton B, Sable J, Hoffman L. Characteristics of the 100 Largest Public Elementary and Secondary School Districts in the United States: 2003–04. US Department of Education National Center for Education Statistics; 2006. [Google Scholar]