Significance

The immune synapse (IS), the site of cell–cell contact between T cells and antigen-presenting cells, plays a crucial role in the mounting of an immune response. Although IFT20 (intraflagellar transport protein 20), a component of the intraflagellar transport system, regulates polarized traffic to the IS, its role in T-cell activation in vivo is unknown. Here we show that in the absence of IFT20, T-cell receptor (TCR)-mediated signaling and recruitment of the signaling adaptor LAT to the immune synapse are impaired, leading to defective CD4+ T-cell activation and proliferation. IFT20-defective mice fail to mount effective antigen-specific T-cell responses, and their T cells do not induce disease in a T-cell-adoptive transfer model of colitis.

Keywords: CD4+ T cell, intraflagellar transport, vesicular traffic, colitis, adoptive transfer

Abstract

Biogenesis of the immune synapse at the interface between antigen-presenting cells and T cells assembles and organizes a large number of membrane proteins required for effective signaling through the T-cell receptor. We showed previously that the intraflagellar transport protein 20 (IFT20), a component of the intraflagellar transport system, controls polarized traffic during immune synapse assembly. To investigate the role of IFT20 in primary CD4+ T cells in vitro and in vivo, we generated mice bearing a conditional defect of IFT20 expression in T cells. We show that in the absence of IFT20, although cell spreading and the polarization of the centrosome were unaffected, T-cell receptor (TCR)-mediated signaling and recruitment of the signaling adaptor LAT (linker for activation of T cells) at the immune synapse were reduced. As a consequence, CD4+ T-cell activation and proliferation were also defective. In vivo, conditional IFT20-deficient mice failed to mount effective antigen-specific T-cell responses, and their T cells failed to induce colitis after adoptive transfer to Rag−/− mice. IFT20 is therefore required for the delivery of the intracellular pool of LAT to the immune synapse in naive primary T lymphocytes and for effective T-cell responses in vivo.

Vesicular traffic has emerged as a central player in the assembly and function of the immune synapse (IS), the specialized interface that forms at the T-cell membrane on contact with an antigen-presenting cell (APC) bearing cognate peptide–MHC complexes. Indeed, polarized recycling of several receptors (1, 2), including the T-cell receptor (TCR) (3), has been shown to control the clustering of these receptors at the synaptic zone and to sustain signaling initiated by their engagement. It is now well established that vesicular traffic to the IS is coopted not only by receptors but also by membrane-associated signaling mediators that are required for signal initiation and amplification, the most prominent being the kinase Lck and the adaptor LAT (linker for activation of T cells) (4, 5). These molecules are carried to the IS by recycling endosomes that move along microtubular tracks toward the centrosome, which polarizes just below the IS on contact with the cognate APC (6).

We have recently provided evidence that the intraflagellar transport protein 20 (IFT20) (7) and other components of the intraflagellar transport (IFT) system, which regulates the assembly of the primary cilium (8), act as unconventional players in IS assembly by selectively controlling the polarized traffic of recycling TCRs and other recycling receptors, such as the transferrin receptor (TfR) (9, 10). We investigate here the role of IFT20 in T-cell activation, using a conditional knockout mouse carrying a null IFT20 allele in T cells. We show that IFT20 is required for TCR signaling, IS formation, and recruitment to the TCR activation sites of vesicular LAT downstream of centrosome polarization. These defects in TCR-induced signaling of IFT20-deficient T lymphocytes translate to an inability to mount an antigen-specific T-cell response both ex vivo and in vivo. We also provide evidence of the physiological relevance of these findings by showing that IFT20 deficiency affects disease severity and outcome in a mouse model of CD4+ T-cell-driven colitis.

Results and Discussion

IFT20 Controls TCR-Induced Signaling.

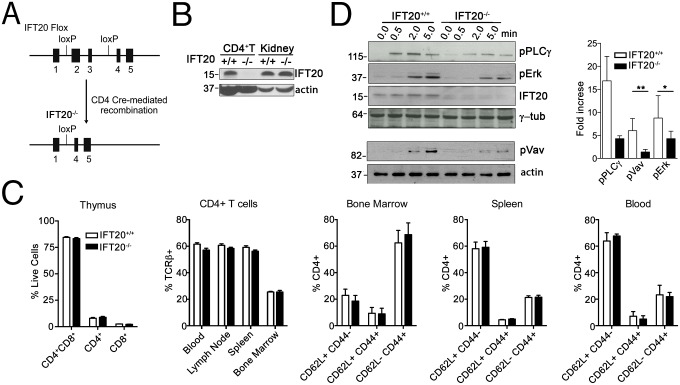

We previously reported that IFT20 regulates vesicular trafficking to the IS in human T cells (9, 10). To achieve insights into the role of IFT20 in T cells in vivo, we crossed transgenic mice expressing the Cre recombinase under the control of a CD4 minigene with mice in which the Ift20 locus was flanked by loxP sites upstream of exon 2 and downstream of exon 3 (11) (Fig. 1A). This strategy led to a complete loss of IFT20 expression in CD4+ T cells (Fig. 1B). The percentages and numbers of DP and CD4+ or CD8+ T cells in the thymus were normal (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1A), suggesting there was no gross perturbation in T-cell development, in agreement with a recent report (12). The percentages and numbers of CD4+/TCRβ+ T cells in blood, lymph nodes (LN), spleen, and bone marrow were also normal, showing that IFT20 deficiency affects neither CD4+ T-cell egress from the thymus nor their homeostasis in the periphery (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1A). Finally, the percentages and numbers of CD62L+/CD44− (naive), CD62L+/CD44+ (central memory), and CD62L−/CD44+ (effector memory) were comparable in IFT20+/+ and IFT20−/− CD4+ T cells purified from bone marrow, spleen, and blood (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1B), suggesting peripheral T-cell differentiation was normal.

Fig. 1.

TCR signaling is impaired in IFT20-deficient mice. (A) Mice containing LoxP sites in introns 1 and 3 were crossed to CD4-Cre mice generating T-cell-specific IFT20-deficient mice. (B) Western blot showing IFT20 expression in lysates of CD4+ T cells and kidney as negative control (representative of n = 5). (C) Mean percentages of lymphocyte populations from adult IFT20+/+ or IFT20−/− mice analyzed by FACS. Data compiled from three experiments (n = 9). (D) Immunoblot analysis of IFT20+/+ and IFT20−/− naive CD4+ T cells unstimulated (0.0) or activated with α-CD3 and α-CD28 mAbs (1 μg/mL) for the indicated times. The histogram shows the quantification of the 0- and 5-min points. Data are normalized to the loading control and presented as fold-induction of phosphorylation in response to CD3+CD28 stimulation (mean ± SEM) (n ≥ 3). Statistical significance was calculated using a ratio paired t test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Fig. S1.

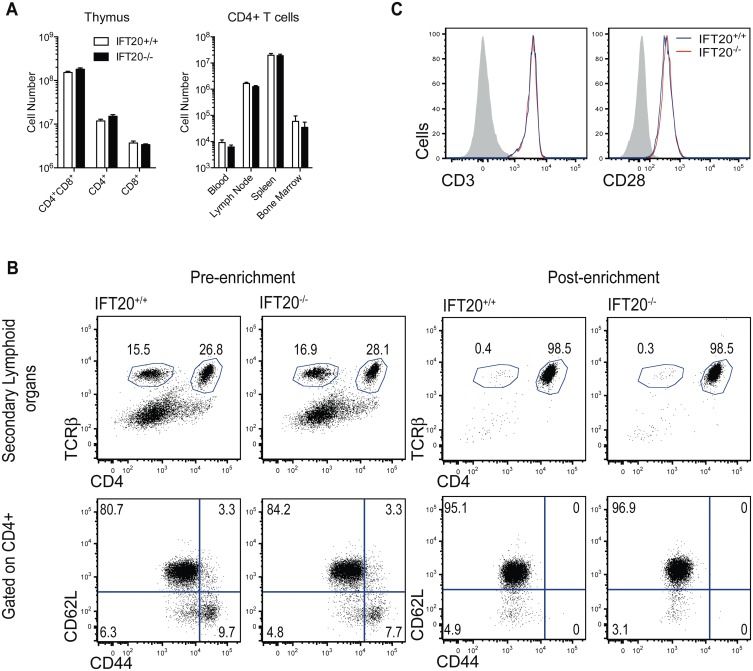

(A) Numbers of double-positive and single-positive thymocytes and numbers of CD4+ T lymphocytes in different tissues from adult IFT20+/+ or IFT20−/− mice analyzed by FACS. Data compiled from three experiments (n = 9). (B) Representative FACS profiles of CD3 (Left) and CD28 (Right) expression on IFT20+/+ (blue line) or IFT20−/− (red line) CD4+ T cells. Isotype controls are shown in shaded gray histograms. (C, Top) Representative FACS profiles of TCRβ and CD4 expression on cells collected from secondary lymphoid organs from IFT20+/+ or IFT20−/− mice preenrichment (Left) or postenrichment (Right) for naive CD4+ T cells. (Bottom) Representative FACS profiles of CD62L and CD44 expression on cells collected from secondary lymphoid organs from IFT20+/+ or IFT20−/− mice preenrichment (Left) or postenrichment (Right) for naive CD4+ T cells.

Fig. S2.

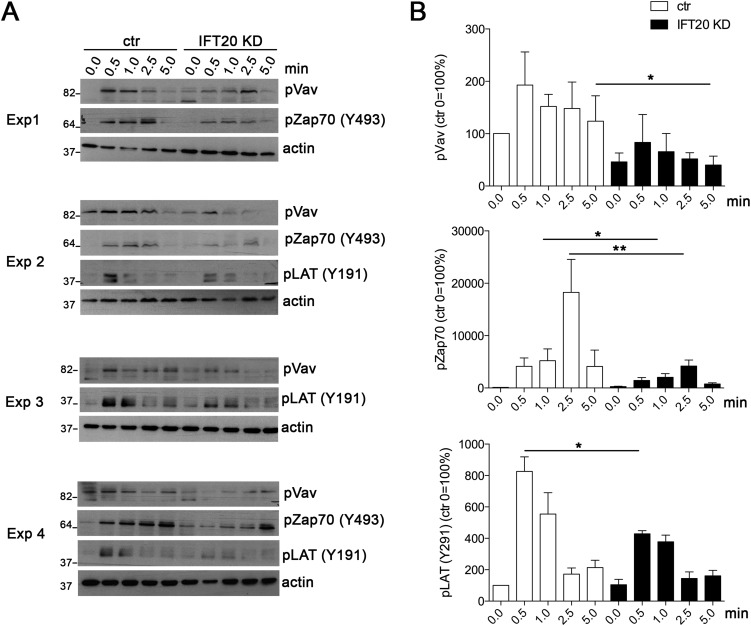

(A) Immunoblot analyses of control (ctr) and IFT20 KD Jurkat cells unstimulated or activated for the indicated times with α-CD3 and α-CD28 mAb (1 μg/mL). Four different experiments are shown. (B) Quantification of the immunoblot analyses of control (ctr) and IFT20 KD Jurkat cells shown in A. Data are normalized to the loading control and presented as percentage of the unstimulated ctr sample (ctr, 0.0) set as 100%; mean ± SEM (n ≥ 3). Statistical significance was calculated using a ratio paired t test. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01.

However, stimulation of IFT20-deficient CD4+ T cells by CD3+CD28-specific mAbs led to a reduced induction of phosphorylation of PLC-γ1 (phospholipase C γ), Vav, and the MAPKs (mitogen-activated protein kinase) Erk1/2 (extracellular signal-regulated kinase) compared with control littermate T cells (Fig. 1D). Similarly, TCR-induced signaling, namely, phosphorylation of Zap70, Vav, and LAT, was found to be impaired in Jurkat T cells silenced for IFT20 (Fig. 2A). These results confirm and extend our previous results obtained in human primary T cells, as well as Jurkat T cells (9), by showing that IFT20 is required for early signaling in primary murine T lymphocytes. The defect in TCR triggering reported here may be attributed to the role of IFT20 in endosome recycling. Indeed, IFT20 deficiency has been shown to affect TCR and TfR recycling (9, 10), and might similarly affect recycling of signaling molecules that control early TCR triggering.

Fig. 2.

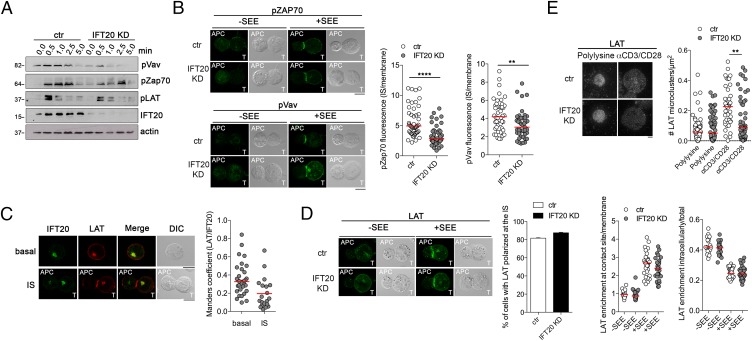

Deficiency of IFT20 inhibits intracellular LAT recruitment to TCR activation sites while not affecting membrane LAT clustering at the IS. (A) Immunoblot analysis of control (ctr) and IFT20 KD Jurkat cells, unstimulated (0.0) or activated for the indicated time with α-CD3 and α-CD28 mAbs (1 μg/mL). Quantifications are shown in Fig. S2. A representative experiment is shown (n ≥ 3). (B) Confocal micrographs showing pZap70 and pVav recruitment to the IS in conjugates of control (ctr) or IFT20 KD Jurkat cells and Raji cells either unpulsed or pulsed with staphylococcal enterotoxin E (SEE). The graphs on the right show the relative pZap70 and pVav fluorescence at the T-cell:APC contact site. The red bars indicate the median for each data set. Measurements were taken on 50 conjugates from four independent experiments. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (C) Quantification using Mander's coefficient of the weighted colocalization of LAT with IFT20 in Jurkat cells, either as such or after conjugation with SEE-pulsed Raji cells. The red bars indicate the median for each data set. At least 20 cells were analyzed (n ≥ 2). (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (D) Confocal micrographs showing LAT recruitment to the IS in conjugates of control (ctr) or IFT20 KD Jurkat cells and Raji cells either unpulsed or pulsed with SEE. The graphs show the percentage of conjugates harboring LAT at the IS (mean ± SEM) (Right) and the relative LAT fluorescence at the T-cell:APC contact site and in the intracellular pool (Lower Right and Left). The red bars indicate the median for each data set. Measurements were taken on 30 conjugates from two independent experiments. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (E) TIRF analysis of the recruitment of LAT microclusters to the interface between coverslips coated with α-CD3 and α-CD28 mAbs and ctr and IFT20 KD Jurkat cells (Left). The single cell graph shows the number of LAT microclusters/μm2. The red horizontal bars indicate the median for each data set (n = 2). Statistical significance was calculated using a nonparametric unpaired t test; **P < 0.01. (Scale bar, 10 μm.)

IFT20 Controls the Recruitment of LAT to TCR Activation Sites.

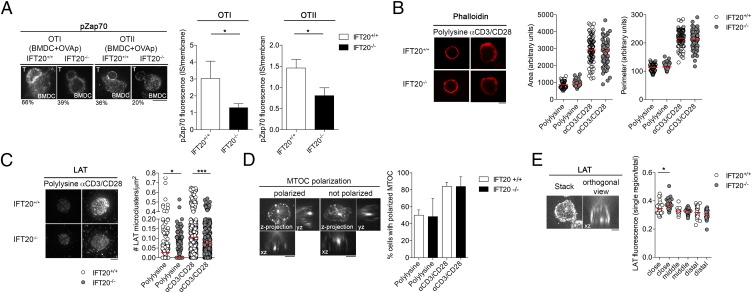

Given the observed impairment of TCR-mediated signaling, we next analyzed the recruitment and activation of Zap70, a tyrosine kinase essential for TCR signaling (13), at the IS of IFT20-deficient T cells. For these experiments, we used T cells purified from Ift20fl/flCD4-Cre mice crossed with OTI or OTII mice, which express a transgenic TCR specific for peptides derived from hen ovalbumin (OVA) in the context of H2Kb or I-Ab, respectively. Phospho-Zap70 (pZap70; phosphorylated-ζ-chain–associated protein kinase) recruitment to the IS was analyzed by confocal microscopy in CD4+ T lymphocytes incubated with LPS-matured bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDC) pulsed with the specific OVA peptides. The enrichment in pZap70 at the T-cell:APC contact area was reduced for both OTI/IFT20−/− and OTII/IFT20−/− T cells (Fig. 3A), showing that IFT20 expression controls antigen-specific signaling at the IS. Similar results were obtained when pZap70 and pVav recruitment to the IS was analyzed on Jurkat IFT20KD cells (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 3.

Impaired recruitment of LAT and pZap70 to TCR activation sites in IFT20−/− CD4+ T cells. (A) Confocal micrographs of conjugates of IFT20+/+ and IFT20−/− naive CD4+ T cells and BMDC preloaded with OVA peptide. Conjugates were stained with a pZap70 (p-Y493)-specific antibody. The histograms show the ratio of pZap70 fluorescence intensity at the IS compared with the rest of the membrane (mean ± SEM), quantified using ImageJ, whereas the percentages of cells showing pZap70 recruitment to the IS are indicated below the representative images (number of conjugates; OTI: WT = 33, KO = 48; OTII: WT = 54, KO = 47). (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (B) Confocal micrographs of IFT20+/+ and IFT20−/− naive CD4+ T cells plated on coverslips coated with α-CD3 and α-CD28 mAbs or poly-l-lysine as negative control. Cells were stained with phalloidin Alexa-546, and the spreading area and perimeter were measured with ImageJ and presented as arbitrary units (Right). The red horizontal bars indicate the median for each data set (n = 2). (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (C) TIRF micrographs showing the recruitment of LAT microclusters to the interface between coverslips coated with α-CD3 and α-CD28 mAbs and IFT20+/+- and IFT20−/−-naive CD4+ T cells (Left). Single-cell graphs representing the number of LAT microclusters/μm2 are shown on the right. The red horizontal bars indicate the median for each data set (n = 3). Statistical significance was calculated using an unpaired nonparametric t test; *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.005. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (D) Confocal micrographs shown as z-projections and orthogonal views of IFT20+/+ and IFT20−/− naive CD4+ T cells plated on coverslips coated with α-CD3 and α-CD28 mAbs and stained with an anti-α tubulin Ab (Top). Cells were scored on the basis of the polarization of the MTOC to the coverslip and classified as polarized or not polarized, depending on the position of the MTOC (Bottom). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (E) Confocal micrographs shown as single stack and xz orthogonal view from the z-stack of naive CD4+ T cells plated on coverslips coated with α-CD3 and α-CD28 mAbs and stained with an anti-LAT Ab (Left). LAT intensity was measured in three regions with the same area classified as close, middle, and distal to the coverslip. Data are expressed as ratio between LAT intensity in each area and the total LAT intensity of the cell. The red horizontal bars indicate the median for each data set (n = 2). Statistical significance was calculated using an unpaired nonparametric t test. *P < 0.05. (Scale bar, 10 μm.)

IS formation is accompanied by T-cell spreading resulting from actin remodeling (14). To analyze this event, IFT20−/− CD4+ T cells were incubated on coverslips coated with CD3+CD28-activating mAbs or poly-l-lysine as control. F-actin was labeled with fluorescent phalloidin, and the cell area and perimeter were measured using Image J software. Activation by CD3+CD28-specific mAbs induced spreading of T cells compared with poly-l-lysine. No defect in spreading was observed in IFT20-deficient CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3B).

LAT, a key adaptor protein involved in T-cell development and activation (15, 16), has been shown to be present not only at the plasma membrane but also in subsynaptic vesicles that are rapidly recruited to activation sites in T lymphocytes (17–19). LAT has also been shown to partially colocalize with the TfR, strongly suggesting it undergoes recycling (5). Given the role of IFT20 in TfR recycling (10), we studied the relative localization of IFT20 and LAT. Confocal imaging of Jurkat cells costained for LAT and IFT20 showed a significant colocalization of IFT20 with the vesicular pool of LAT (Fig. 2C), which decreased after IS assembly, raising the possibility that IFT20 may be involved not only in TCR and transferrin receptor recycling (9, 10) but also in the traffic of vesicular LAT. To measure LAT recruitment, we incubated CD4+ T cells on coverslips coated with CD3+CD28-activating mAbs, or poly-l-lysine as control, and performed total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRFM) on cells fixed and labeled with anti-LAT Abs, as previously described (19). We observed a significant reduction in LAT recruitment to the TCR activation sites in IFT20−/− CD4+ T cells, as shown by the lower density of LAT microclusters in the evanescent field (Fig. 3C). This was not a result of defective expression of CD3 or CD28 by these cells, as assessed by flow cytometry (Fig. S1C).

Recruitment of the intracellular pool of LAT, which is triggered by the TCR and requires several signaling mediators, including LAT itself (5), is controlled by centrosome polarization (20). We measured the polarization of the centrosome toward the coverslips in wild-type and IFT20−/− CD4+ T cells in the same experimental setting used for the analysis of LAT recruitment. No defect in centrosome polarization to the IS was observed in IFT20−/− CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3D), similar to our previous observation on human T cells (7). This indicates that the signals triggered by the TCR in IFT20−/− T cells, although less robust than the signals triggered in wild-type T cells (Fig. 1D), are sufficient to promote centrosome translocation.

Of note, when the recruitment of LAT was quantified on confocal orthogonal images of the same slides used for TIRFM, no defect of polarization of LAT in the third of the cell nearest to the activating slide was observed in the IFT20−/− CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3E). Confocal imaging of IFT20-depleted Jurkat cells conjugated to staphylococcal enterotoxin E (SEE)-pulsed Raji cells showed that LAT (which, as a result of the resolution limits of this type of analysis, was likely to include both plasma membrane LAT and subsynaptic LAT+ vesicles) was normally mobilized to the IS (Fig. 2D). However, similar to mouse primary IFT20−/− T cells, recruitment of LAT measured by TIRFM was decreased in IFT20-depleted Jurkat cells activated on slides coated with anti-CD3+CD28 Abs (Fig. 2E). Taken together with the colocalization of IFT20 with vesicular LAT (Fig. 2C), these results suggest that IFT20 regulates the last step of traffic of the vesicular pool of LAT that is normally polarized in IFT20-deficient T cells but does not reach or does not dock to the plasma membrane in the synaptic zone.

Collectively, these results show that IFT20 acts as a central regulator of IS formation in primary CD4+ T cells by affecting essential events triggered by the TCR downstream of centrosome polarization, which can be accounted for not only by the defect in polarized TCR recycling reported previously (9, 10) but also by a defect in the traffic of vesicular LAT to the TCR activation sites.

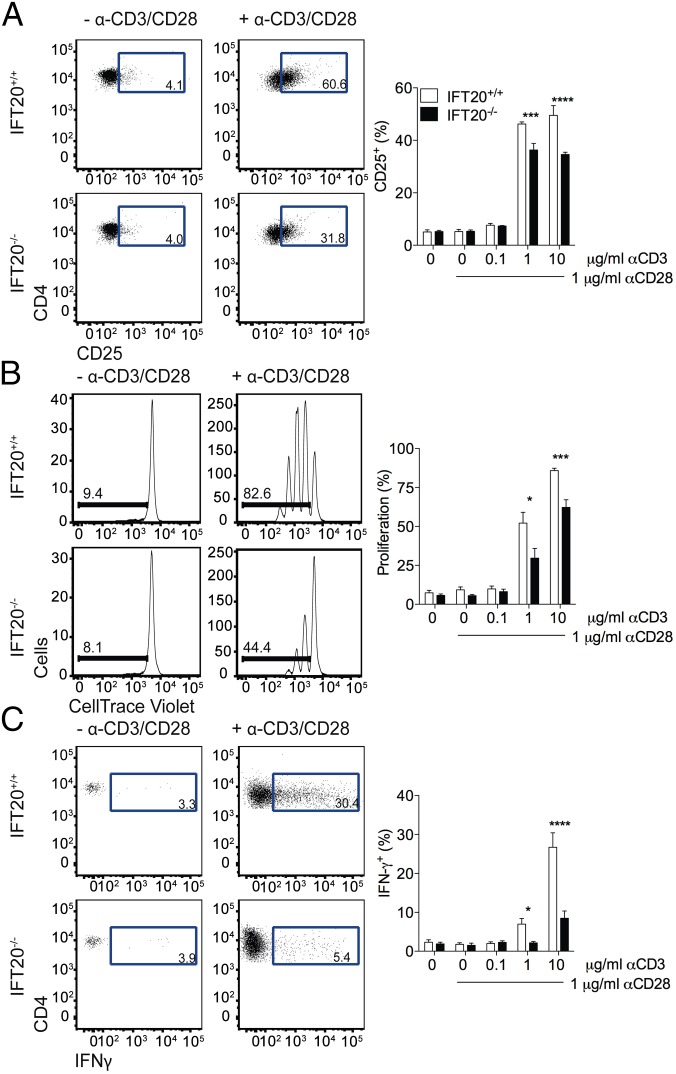

IFT20 Controls ex Vivo Activation of T Lymphocytes.

To next address the potential role of IFT20 in T-cell activation, CD4+ T cells were purified from spleens and LNs and activated ex vivo, using different concentrations of CD3+CD28-specific mAbs. Expression of CD25 (Fig. 4A), proliferation (Fig. 4B), and IFNγ production in the supernant (Fig. 4C) were reduced in IFT20−/− CD4+ T cells compared with their wild-type counterparts, demonstrating that IFT20 expression is required for efficient activation of CD4+ T cells.

Fig. 4.

Impaired activation of CD4+ T cells in vitro. (A) CD25 expression was analyzed by FACS after 20 h of culture of total CD4+ T cells isolated from spleens and LNs in the presence or absence of α-CD3 (10 μg/mL) and α-CD28 (1 μg/mL) mAbs (Left) or the indicated concentrations of α-CD3 and α-CD28 mAbs (Right). Cell proliferation (B) and IFNγ expression (C) were analyzed after 72 h of culture in the presence or absence of α-CD3 (10 μg/mL) and α-CD28 (1 μg/mL) mAbs (Left) or the indicated concentrations of α-CD3 and α-CD28 mAbs (Right). Error bars represent SEM (n = 3). Statistical significance was calculated using Student's t test. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.005; ****<0.001.

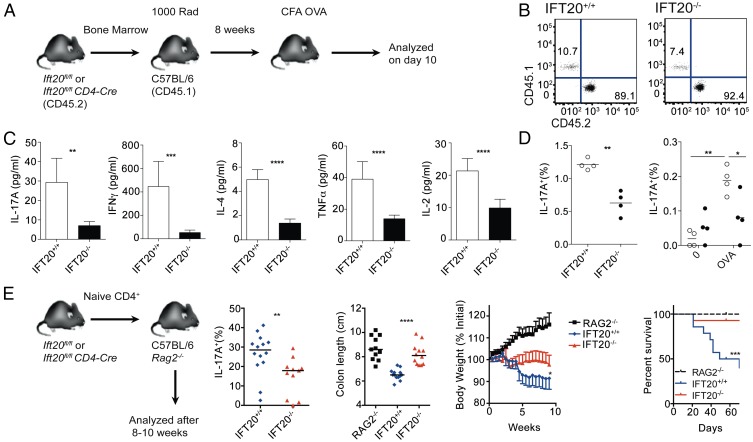

IFT20 Controls T Cell Functions in Vivo.

To test whether IFT20 controls TCR-induced T-cell activation in vivo, we first checked the T-cell response to an antigenic challenge. Lethally irradiated WT CD45.1 C57BL6 mice were reconstituted with bone marrow from CD45.2 Ift20fl/flCD4-Cre mice and Ift20fl/fl controls (Fig. 5A). Reconstitution of the T-cell compartment was comparable in chimeras generated with bone marrows from Ift20fl/flCD4-Cre and from Ift20fl/fl littermate controls (Fig. 5B). The mouse chimeras were immunized with OVA in complete Freund adjuvant, and 10 days after immunization, splenocytes were restimulated in vitro in the presence of OVA. Concentrations of cytokines present in the supernatants were measured 24 h later. Production of all cytokines tested (IL-17A, IFNγ, IL-4, TNF-α, and IL-2) was reduced in IFT20−/− CD4+ T lymphocytes (Fig. 5C). The impairment in IL-17A production by IFT20−/− CD4+ T lymphocytes after in vitro restimulation with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA)+ionomycin or OVA was confirmed by intracellular staining (Fig. 5D). These results show that expression of IFT20 by T cells is required for mounting a CD4+ T-cell response after immunization.

Fig. 5.

Impaired CD4+ T-cell response in IFT20-deficient mice. (A) Bone marrow (BM) chimeras were generated by reconstituting lethally irradiated WT CD45.1 mice with BM from Ift20fl/fl or Ift20fl/flCD4-Cre mice (CD45.2). (B) The ratio of CD45.1+ and CD45.2+ CD4+ T cells in the spleens of chimeric mice in a representative experiment is shown. (C) Cytokine production by splenocytes from mice 10 d after immunization with complete Freund’s adjuvant OVA was assessed by cytometric bead array (CBA) after 24 h of OVA restimulation. Error bars represent SEM (n = 4 mice; data from two experiments). (D) Intracellular flow cytometric analysis of total IL-17A production in CD4+ cells after PMA+ionomycin restimulation (Left) and antigen-specific IL-17A production in CD4+ T cells restimulated with OVA. The horizontal bars represent the median (n = 4 mice) data from two experiments. (E) Colitis was induced by transfer of FACS-sorted naive CD4+ T cells into C57BL6 Rag2−/− mice. Mice were killed 8–10 wk after transfer or upon losing 20% of their initial body weight. IL-17A production in CD4+ T cells from mesenteric LNs from mice reconstituted with IFT20+/+ (blue diamonds) or IFT20−/− (red triangles) BM. Colon length at time of sacrifice of Rag2−/− mice (black squares), mice reconstituted with IFT20+/+ (blue diamonds), or IFT20−/− (red triangles) BM. Percentage initial body weight of Rag2−/− mice (black squares), mice reconstituted with IFT20+/+ (blue diamonds), or IFT20−/− (red triangles) BM. Survival curve of Rag2−/− mice (black dashed line), mice reconstituted with IFT20+/+ (blue solid line) or IFT20−/− (red solid line) BM. Data compiled from two experiments (n = 14 mice per group). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005; ****P < 0.001. Statistical significance was calculated using Student's t test (C and D) or one-way ANOVA (E).

To further analyze the role of IFT20 in T-cell activation, we used a T-cell-induced model of colitis. Naive CD4+ T cells purified from Ift20fl/flCD4-Cre mice and Ift20fl/fl control littermates were transferred into C57BL6 Rag2−/− mice. In this model, the T-cell transfer in immunodeficient mice induces a chronic colitis (21). Because IL-17A was shown to be critical for T-cell-mediated colitis (22), mice were killed and CD4+ T lymphocytes were purified from mesenteric LNs and activated with PMA+ionomycin to reveal their ability to produce IL-17A. The percentages of IL-17A+CD4+ T cells were lower in LNs from Ift20fl/flCD4-Cre mice compared with Ift20fl/fl control littermates (Fig. 5E). To appreciate the intestinal inflammation in the model, we measured the length of the colon. Colons from Rag2−/− mice reconstituted with CD4+ T cells from control mice were significantly shorter than colons from Rag2−/− recipient mice (Fig. 5E). In contrast, colons from Rag2−/− mice reconstituted with IFT20-deficient CD4+ T cells did not show any significant modification of their length (Fig. 5E). Finally, survival of the mice transferred with IFT20−/− CD4+ T cells was not altered compared with that of control Rag2−/− mice, whereas under the same conditions, the transfer of wild-type CD4+ T cells resulted in premature death of the mice or their being killed because of a weight loss of more than 20% of their initial body weight (Fig. 5E). Collectively, these results show that IFT20−/− CD4+ T cells have a strongly reduced pathogenicity, which is most probably a result of their reduced production of IL-17A, and possibly other proinflammatory cytokines. Interestingly, a recent report showed that ift20 deletion in CD4 T cells has only mild effects on the development of collagen-induced arthritis (12), another T-cell-related autoimmune disorder. Although the pattern of cytokine production was not investigated in that report, the effect of IFT20 deficiency on the development of pathogenic Th17 cells may have been underestimated in this experimental model, which involves the use of a potent adjuvant.

The data presented in this report extend and validate in vivo the role that IFT20 plays in IS assembly by regulating the traffic to the T-cell:APC interface not only of endosome-associated TCRs (9) but also of the endosomal pool of LAT, which acts as a scaffold for the assembly of multimolecular complexes that amplify TCR-generated signals. LAT is present both at the plasma membrane and in intracellular pools, which are recruited to the TCR activation sites (5, 17–19). Both pools have been shown to play a role in T-cell activation (18, 19, 23, 24). We show here that LAT fails to reach this membrane-proximal location in IFT20-deficient T cells (Figs. 2E and 3C) despite polarization of the centrosome (Fig. 3D). However, LAT-dependent signaling is not completely abolished, suggesting the plasma membrane pool of LAT can still signal, but the subsynaptic vesicular pool cannot.

It is worth noting that although partial, the signaling defect induces an important functional T-cell defect in vivo. Indeed, IFT20 deficiency results in a defect in the production of all the cytokines tested, including Th1, Th2, and Th17 cytokines. This result suggests the T-cell differentiation defects observed in IFT20fl/fl/CD4Cre mice are the consequence of the impaired ability of CD4+ T cells to become activated in response to TCR signaling, rather than of a selective defect in their differentiation. Although we favor the explanation that the defect in TCR signaling in IFT20−/− T cells causes these defects in the biological response, we cannot at this stage rule out that IFT20 is implicated in the regulation of other pathways that control cytokine production. Moreover, it is possible that we underestimated the TCR signaling defect in our in vitro experiments where T lymphocytes are activated with high concentrations of anti-CD3+CD28 Abs. In in vivo conditions, triggering of the TCR is likely to be much lower, thus allowing us to better reveal the functional outcome of IFT20 deficiency.

In conclusion, the results presented here show that, in primary mouse CD4+ T lymphocytes, IFT20 expression is required for TCR-induced signaling, recruitment of vesicular LAT to the TCR activation sites, and CD4+ T-cell function in vivo. IFT20 is a component of the IFT system that controls the assembly of the primary cilium (8). Based on our finding that a number of components that regulate this process are implicated in vesicular traffic to the IS in T cells (9, 10, 25, 26), studying the pathways that control ciliogenesis should provide new molecules implicated in IS assembly and function.

Materials and Methods

Mice, Cells, Reagents, and Antibodies.

Mice with T-cell-specific deletion of IFT20 were generated by crossing Ift20fl/fl mice (11) with CD4-Cre mice. OTI and OTII mice were crossed to Ift20fl/flCD4-cre mice to obtain Ift20fl/flCD4-Cre OTI and Ift20fl/flCD4-Cre OTII mice, respectively. Further details are provided in the SI Materials and Methods.

Purification of naive CD4+ T cells from LNs and spleens was carried out as detailed in the SI Materials and Methods. BMDC were differentiated as described previously (27). Details on the activation of BMDC, loading with either class I (OVA257–264) or class II (OVA323–339) peptide and incubation with OTI and OTII cells, respectively, are provided in the SI Materials and Methods.

Cell lines include Jurkat T cells and Raji B cells. Stable IFT20 knock-down Jurkat cells (IFT20 KD; ∼70% depletion) were previously described (9).

Anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 mAbs used for T-cell activation as well as other Abs and reagents are listed in the SI Materials and Methods.

BM Chimeras.

BM chimeras were generated as detailed in the SI Materials and Methods.

Immunizations.

The protocol for immunization is described in the SI Materials and Methods.

Colitis.

Colitis was induced by i.v. injection of FACS-sorted naive CD4+ T cells from ift20fl/fl or ift20fl/fl CD4-cre donor mice into age-matched Rag2−/− recipients and scored as described in the SI Materials and Methods.

Flow Cytometry.

The protocols for flow cytometric analysis of surface markers and intracellular cytokines are described in the SI Materials and Methods.

T-Cell Proliferation Assay.

T-cell proliferation assays were carried out as described in the SI Materials and Methods.

Immunoblots.

Jurkat cells and mouse CD4+ T cells were processed for immunoblot as described in the SI Materials and Methods.

Microscopy and Image Analysis.

The detailed protocols for confocal imaging and TIRF microscopy of mouse CD4+ T cells and Jurkat cells are described in the SI Materials and Methods. TIRFM images were analyzed with ImageJ software as described (28), using the strategy detailed in the SI Materials and Methods.

Statistical Analysis.

Unpaired Student’s t test, unpaired nonparametric t test, ratio paired t test, and one-way ANOVA test were used for statistical analysis. SEM and P values were determined using Prism software.

SI Materials and Methods

Mice, Cells, and Reagents.

C57BL/6 were purchased from Charles River. CD45.1 C57BL/6, Rag2−/− OTI, OTII, CD4-Cre mice were purchased from Jackson laboratory. Ift20fl/fl mice were previously described (11). Mice with T-cell-specific deletion of IFT20 were generated by crossing Ift20fl/fl mice to CD4-Cre mice. OTI and OTII mice were crossed to Ift20fl/flCD4-cre mice to obtain Ift20fl/flCD4-Cre OTI and Ift20fl/flCD4-Cre OTII, mice respectively. Experiments were performed on 6–12-wk-old mice. All mice were housed in the pathogen-free animal facility of the Institut Curie, and experiments were done in accordance with the guidelines of the European Veterinary Department.

Polyclonal CD4+ T cells were obtained from lymph nodes and spleens, and total or naive cells were isolated using negative selection (EasySep Mouse CD4+ T-cell isolation kit; EasySep Mouse Naive CD4+ T-cell isolation kit, Stemcell Technologies; purity ≥ 95%; Fig. S1C). Naive CD8+ T cells were isolated from lymph nodes and spleens using negative selection (EasySep Mouse Naive CD8+ T-cell isolation kit, Stemcell Technologies; purity ≥ 95%) Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells were differentiated as described previously (27). Cells collected after 7–10 d of culture were activated overnight with 100 ng/mL LPS (InvivoGen), loaded with either class I (OVA257–264) or class II (OVA323–339) peptide (InvivoGen) for 1 h at 37 °C, and washed extensively before incubation with OTI and OTII cells, respectively.

Cell lines include Jurkat T cells and Raji B cells, both of human origin. Stable IFT20 knock-down Jurkat cells (IFT20 KD) were obtained as described (14), using two pGP676.13 plasmids containing the complementary oligonucleotides corresponding to the coding region of human IFT20.

Jurkat cells were activated with anti-CD3ε (OKT3; 16–0037-85; eBioscence) and anti-CD28 (CD28.2; 302914; Biolegend) mAbs. Mouse CD4+ T cells were activated with anti-mouse CD3ε (145-2C11; 553057; BD Pharmingen) and anti-mouse CD28 (37.51; 553294; BD Pharmingen) mAbs. SEE was from Toxin Technology, and poly-l-lysine from Sigma Aldrich (P8920).

Antibodies.

The following primary antibodies were used: anti-IFT20 (29), anti-IFT20 (13615-1-AP; Proteintech), anti-pPLCγ (Tyr783; #2821; CST), anti-pVAV (Tyr-160; 44482; Invitrogen), anti-pZAP-70 (Tyr319; #2701; CST), anti-pERK (Thr202/Tyr204; #4376; CST), anti-pLAT (Tyr191; #3584; CST), anti-actin (MABT219; Millipore), and anti-α-Tubulin (DM1A; Ebioscience). Peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech. Alexa-Fluor 488 and Alexa-Fluor 546-labeled secondary antibodies and Phalloidin-546 were from Invitrogen.

BM Chimeras.

C57BL/6 CD45.1 host animals were lethally irradiated (137Cs source) and reconstituted with donor BM by i.v. injection of at least 5 × 106 cells from 6–8-wk-old CD45.2 ift20fl/fl or ift20fl/fl CD4-cre donor mice. Mice were tested for chimerism 6–8 wk after reconstitution by flow cytometry.

Immunizations.

Mice were immunized in the left flank with a mixture of 100 μg OVA (Worthington) emulsified in complete Freund’s adjuvant (DIFCO ref. 263810) or in endotoxin-free PBS in a total volume of 100 μL (ratio 1:1). Ten days after immunizations, pools of splenocytes were restimulated ex vivo in triplicate with PMA (10 ng/mL)/ionomycin (1 μg/mL) (Sigma) for 4 h, or OVA (50 μg/mL) for 24 h, and processed for flow cytometry.

CD4 Adoptive Transfer Model of Colitis.

Polyclonal CD4+ T cells were obtained from lymph nodes and spleens of 6–8-wk-old ift20fl/fl or ift20fl/fl CD4-cre donor mice, and naive cells were isolated by FACS sorting. Next, 5 × 105 naive CD4+ T cells were injected i.v. into age-matched Rag2−/− recipients. Mice were monitored for onset of disease and were weighed twice per week. Mice were killed on losing 20% of their initial body weight or after 8–10 wk, and mesenteric lymph nodes and colons were collected. Mesenteric lymph nodes were analyzed for IL-17A expression by intracellular FACS.

Flow Cytometry.

Single-cell suspensions were prepared in FACS buffer [PBS 0.5% (wt/vol) BSA, 2 mM EDTA], and depending on the experiment, cells were labeled with anti-CD4 (RM4-5), anti-CD8 (53-6.7), anti-CD69 (H1.2F3), anti-CD25 (7D4), anti-CD62L (MEL-14), anti-CD44 (IM-7), anti-IFNγ (XMG1.2), anti-TCRβ (H57-597), anti-CD3ε (145-2C11), anti-CD45.1 (A20), or anti-CD45.2 (1O4) fluorochrome-labeled specific mAbs and isotype controls purchased from BD. Anti-IL-17A (eBio17B7) and isotype control were purchased from eBioscience. Anti-CD28 (E18) and isotype control were purchased from Biolegend. Before staining, cells were preincubated with Fc receptor blocking antibody (2.4 G2) from BD. Dead cells were stained with LIVE/DEAD fixable green kit (Invitrogen) or fixable viability dye eFluor780 (eBioscience), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Supernatants were collected after 24 h of restimulation and analyzed with the BD mouse Th1/Th2/Th17 cytometric bead array kit. Intracellular FACS analysis of cytokine production was performed with the Foxp3/Transcription factor staining buffer set (BD) by adding Golgi-Plug (BD) 10 h before the end of restimulation. Data were collected on a FACSVerse flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) and analyzed using FlowJo software.

T-Cell Proliferation Assay.

Total CD4+ T cells were stained with 2.5 μM CellTrace Violet (Invitrogen), plated on flat-bottom 96-well plates coated with anti-CD3 mAb, and incubated with soluble anti-CD28 mAb at 2 × 105 cells/mL. Cells were analyzed for activation markers after 20 h of stimulation and for proliferation after 72 h of stimulation.

Immunoblots.

Jurkat cells and naive mouse CD4+ T cells (2 × 106) were activated for the indicated times with anti-CD3 (1 μg/mL) and anti-CD28 (1 μg/mL) mAbs in RPMI 1640. Cell were washed with cold PBS and lysed in 50 mM Tris at pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1% (vol/vol) glycerol, 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, and 0.5 mM EDTA, supplemented with 1 mM Na3OV4, 5 mM NaF, and 1× complete, Mini, EDTA-Free Protease Inhibitor Mixture Tablet (11-836-170-001; Roche) or Protease Inhibitor Mixture Set III, EDTA-Free (Calbiochem). Postnuclear supernatants were resolved by SDS/PAGE and were transferred to membranes (Immunoblot PVDF membrane, Bio-Rad). IFT20 deficiency in mouse IFT20−/− and IFT20KD Jurkat cells (>70% depletion) was checked by immunoblot in all lysates.

Microscopy.

For TIRF microscopy, mouse naive CD4+ T cells (2 × 105) or Jurkat cells (1 × 105) were incubated for 20 min at room temperature on coverslips precoated with 0.02% (wt/vol) poly-l-lysine alone or followed by overnight incubation at 4 °C with α-CD3 (10 μg/mL) and α-CD28 (10 μg/mL) mAb. For the IS experiments with OTI mouse CD8+ T cells and OTII mouse CD4+ T cells, BMDC were loaded for 1 h at 37 °C with OVA peptide and labeled with 2.5 μM CellTrace Violet. Cells were extensively washed in RPMI 1640, mixed with mouse CD4+ T cells (1:1), incubated for 15 min at 37 °C, and plated on poly-l-lysine coated slides. For the IS experiments with Jurkat cells, Raji cells were loaded for 2 h at 37 °C with 10 μg/mL SEE and labeled with 10 μM CellTracker Blue for 30 min at 37 °C. Cells were washed with RPMI 1640, mixed with Jurkat cells (1:1), incubated for 15 min at 37 °C and plated on poly-l-lysine-coated slides. Samples were fixed for 20 min at room temperature with 4% (vol/vol) paraformaldehyde in PBS and permeabilized for 20 min with 0.1% (wt/vol) saponin, 1% (wt/vol) BSA in PBS, or for 10 min with 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, 1% (wt/vol) BSA in PBS. Cells were then incubated 1 h and 30 min, respectively, at room temperature, with primary and secondary antibodies diluted in the permeabilizing solution. Coverslips were mounted on glass slides with Fluoromount G (Southern Biotechnology Associates).

Confocal microscopy on Jurkat cells was carried out on a Zeiss LSM510, using a 63× objective. Z-series of optical sections were performed at 0.5-μm increments. Detectors were set to detect an optimal signal below the saturation limits. Image sets to be compared were acquired using the same acquisition settings. Images were processed using ImageJ software (NIH). A scanning confocal microscope with Nipkow disk mounted on a TiE Nikon microscope was used to perform confocal microscopy on mouse CD4+ T cells. The system was equipped with a piezo-stage NanoScanz mounted on a Marzhauser XYZ motorized scanning stage. The images were recorded on EM-CCD iXon 897 Andor camera. A Nikon TiE microscope equipped with a 100× APO TIRF objective with numerical aperture of 1.45 and an electron-multiplying charge-coupled device camera (Roper Scientific) were used for TIRF microscopy. Metamorph software was used for TIRF acquisitions.

Image Analysis.

Images were analyzed with ImageJ software. LAT fluorescence in CD4+ T cells was measured on the orthogonal xz view from z-stacks, in three different regions with the same area classified as close, middle, and distal to the coverslip. Each fluorescence was then divided by LAT fluorescence in the overall cell. For the measure of LAT fluorescence in Jurkat cells, images were analyzed as described (28). Specifically, the fluorescence intensity of LAT at the IS was divided by the mean of the average intensities measured in three regions of the same size at the plasma membrane outside of the IS. Alternatively, fluorescence intensity of intracellular LAT was divided by the intensity calculated for the entire cell. Analysis of pZap70 and pVav fluorescence at the IS was performed as described for LAT. For quantification of microclusters by TIRFM, a “macro” compatible with ImageJ analysis software was used (available on request).

Acknowledgments

We thank V. Fraisier from the The BioImaging Cell and Tissue Core Facility of the Institut Curie (Pict IBISA) and L. Sengmanivong and the Nikon Imaging Centre @ Institut Curie-CNRS for technical assistance with microscopy and image analysis. O.I.V. was financed by the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer, G.M. by FISM (Fondazione Italiana Sclerosi Multipla), and J.-M.C. by la Ligue contre le Cancer. C.H. was supported by ANR-13-BSV2-0018 “NeuroImmunoSynapse” and la Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale. The financial support of Telethon-Italy (Grant GGP1102) to C.T.B. is gratefully acknowledged. G.J.P. received support from National Institutes of Health (GM060992). S.A. received funding from the Institut Curie, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Ligue Contre le Cancer (Equipe Labellisée EL2014.LNCC/SA), Association de Recherche Contre le Cancer, Grant ERC (2013-AdG No. 340046 DCBIOX), and Labex DC-BIOL. The study was also supported by ANR-10-IDEX-0001-02 PSL* and ANR-11-LABX-0043.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1513601113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Soares H, Lasserre R, Alcover A. Orchestrating cytoskeleton and intracellular vesicle traffic to build functional immunological synapses. Immunol Rev. 2013;256(1):118–132. doi: 10.1111/imr.12110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finetti F, Baldari CT. Compartmentalization of signaling by vesicular trafficking: A shared building design for the immune synapse and the primary cilium. Immunol Rev. 2013;251(1):97–112. doi: 10.1111/imr.12018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Das V, et al. Activation-induced polarized recycling targets T cell antigen receptors to the immunological synapse; involvement of SNARE complexes. Immunity. 2004;20(5):577–588. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehrlich LI, Ebert PJ, Krummel MF, Weiss A, Davis MM. Dynamics of p56lck translocation to the T cell immunological synapse following agonist and antagonist stimulation. Immunity. 2002;17(6):809–822. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00481-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonello G, et al. Dynamic recruitment of the adaptor protein LAT: LAT exists in two distinct intracellular pools and controls its own recruitment. J Cell Sci. 2004;117(Pt 7):1009–1016. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fooksman DR, et al. Functional anatomy of T cell activation and synapse formation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:79–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Follit JA, Tuft RA, Fogarty KE, Pazour GJ. The intraflagellar transport protein IFT20 is associated with the Golgi complex and is required for cilia assembly. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17(9):3781–3792. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-02-0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pedersen LB, Rosenbaum JL. Intraflagellar transport (IFT) role in ciliary assembly, resorption and signalling. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2008;85:23–61. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(08)00802-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finetti F, et al. Intraflagellar transport is required for polarized recycling of the TCR/CD3 complex to the immune synapse. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11(11):1332–1339. doi: 10.1038/ncb1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finetti F, et al. Specific recycling receptors are targeted to the immune synapse by the intraflagellar transport system. J Cell Sci. 2014;127(Pt 9):1924–1937. doi: 10.1242/jcs.139337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jonassen JA, San Agustin J, Follit JA, Pazour GJ. Deletion of IFT20 in the mouse kidney causes misorientation of the mitotic spindle and cystic kidney disease. J Cell Biol. 2008;183(3):377–384. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200808137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuan X, Garrett-Sinha LA, Sarkar D, Yang S. Deletion of IFT20 in early stage T lymphocyte differentiation inhibits the development of collagen-induced arthritis. Bone Res. 2014;2:14038–14049. doi: 10.1038/boneres.2014.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang H, et al. ZAP-70: An essential kinase in T-cell signaling. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(5):a002279. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a002279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dustin ML, Cooper JA. The immunological synapse and the actin cytoskeleton: Molecular hardware for T cell signaling. Nat Immunol. 2000;1(1):23–29. doi: 10.1038/76877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang W, et al. Essential role of LAT in T cell development. Immunity. 1999;10(3):323–332. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang W, Sloan-Lancaster J, Kitchen J, Trible RP, Samelson LE. LAT: The ZAP-70 tyrosine kinase substrate that links T cell receptor to cellular activation. Cell. 1998;92(1):83–92. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80901-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Purbhoo MA, et al. Dynamics of subsynaptic vesicles and surface microclusters at the immunological synapse. Sci Signal. 2010;3(121):ra36. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williamson DJ, et al. Pre-existing clusters of the adaptor Lat do not participate in early T cell signaling events. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(7):655–662. doi: 10.1038/ni.2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larghi P, et al. VAMP7 controls T cell activation by regulating the recruitment and phosphorylation of vesicular Lat at TCR-activation sites. Nat Immunol. 2013;14(7):723–731. doi: 10.1038/ni.2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blanchard N, Di Bartolo V, Hivroz C. In the immune synapse, ZAP-70 controls T cell polarization and recruitment of signaling proteins but not formation of the synaptic pattern. Immunity. 2002;17(4):389–399. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00421-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griseri T, Asquith M, Thompson C, Powrie F. OX40 is required for regulatory T cell-mediated control of colitis. J Exp Med. 2010;207(4):699–709. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yen D, et al. IL-23 is essential for T cell-mediated colitis and promotes inflammation via IL-17 and IL-6. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(5):1310–1316. doi: 10.1172/JCI21404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balagopalan L, Barr VA, Kortum RL, Park AK, Samelson LE. Cutting edge: Cell surface linker for activation of T cells is recruited to microclusters and is active in signaling. J Immunol. 2013;190(8):3849–3853. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soares H, et al. Regulated vesicle fusion generates signaling nanoterritories that control T cell activation at the immunological synapse. J Exp Med. 2013;210(11):2415–2433. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Onnis A, et al. The small GTPase Rab29 is a common regulator of immune synapse assembly and ciliogenesis. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22(10):1687–1699. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finetti F, et al. The small GTPase Rab8 interacts with VAMP-3 to regulate the delivery of recycling T-cell receptors to the immune synapse. J Cell Sci. 2015;128(14):2541–2552. doi: 10.1242/jcs.171652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winzler C, et al. Maturation stages of mouse dendritic cells in growth factor-dependent long-term cultures. J Exp Med. 1997;185(2):317–328. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.2.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tourret M, et al. T cell polarity at the immunological synapse is required for CD154-dependent IL-12 secretion by dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2010;185(11):6809–6818. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pazour GJ, et al. The intraflagellar transport protein, IFT88, is essential for vertebrate photoreceptor assembly and maintenance. J Cell Biol. 2002;157(1):103–113. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200107108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]