Abstract

Background

Several systematic reviews suggest that intermittent pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) chemotherapy is effective, but intensity (daily versus intermittent) and duration of rifampicin use (intensive phase only versus both phases) have not been distinguished. In addition, the various outcomes (success, failure, relapse, and default) have only selectively been evaluated.

Methods

We conducted a meta-analysis of proportions using all four outcomes as multi-category proportions to examine the effectiveness of WHO category 1 TB treatment regimens. Database searches of studies reporting treatment outcomes of HIV negative subjects were included and stratified by intensity of therapy and duration of rifampicin therapy. Using a bias-adjusted statistical model, we pooled proportions of the four treatment outcome categories using a method that handles multi-category proportions.

Results

A total of 27 studies comprising of 48 data sets with 10,624 participants were studied. Overall, treatment success was similar among patients treated with intermittent (I/I) (88%) (95% CI, 81–92) and daily (D/D) (90%) (95% CI, 84–95) regimens. Default was significantly less with I/I (0%) (95% CI, 0–2) compared to D/D regimens (5%) (95% CI, 1–9). Nevertheless, I/I relapse rates (7%) (95% CI, 3–11) were higher than D/D relapse rates (1%) (95% CI, 0–3).

Conclusion

Treatment regimens that are offered completely intermittently versus completely daily are associated with a trade-off between treatment relapse and treatment default. There is a possibility that I/I regimens can be improved by increasing treatment duration, and this needs to be urgently addressed by future studies.

Keywords: Pulmonary tuberculosis, Chemotherapy, Intermittent, Daily

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a global public health problem despite the presence of effective TB pharmacotherapy for more than 50 years and the use of vaccines for more than 90 years. The situation is further compounded by the global HIV pandemic, which has led to unprecedented increases in both TB incidence and mortality in many areas. Consequently, TB treatment programs are faced with high numbers of TB cases coupled with an increase in unfavorable treatment outcomes among patients undergoing TB treatment. The increasing unfavorable TB treatment outcomes are attributed to poor compliance and adherence to TB treatment secondary to high pill burden, toxicity, and adverse reactions, as well as treatment inconvenience, among other factors.1 To mitigate this, intermittent TB treatment regimens have been proposed, and evidence suggests that they achieve a similar treatment outcome to daily regimens.2,3

Today, tuberculosis treatment utilizes four key drugs: ethambutol (E), isoniazid (H), rifampicin (R), and Pyrazinamide (Z). Treatment is in two phases: an initial intensive phase (IP) and a continuation phase (CP). In this paper, the phases are indicated by a slash, and thus 2HRZE/4RH represents 2 months in the intensive phase and 4 months in the continuation phase with drugs used in each phase denoted as letters. Currently, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended the discontinuation of the use of the 8-month treatment regimen that includes only 2 months of rifampicin treatment (2HRZE/6EH) in preference to a 6-month treatment regimen with rifampicin in all 6 months (2HRZE/4RH).4 In addition, the WHO recommends that this TB treatment regimen (2HRZE/4RH) be administered daily, especially in the IP, except where this daily treatment is not possible. In the latter instance, three times weekly dosing is then allowed.4

There is currently no strong evidence that implementation of these daily versus intermittent regimens leads to decreases in treatment failure or relapses, but they certainly are inconvenient and may lead to non-compliance and subsequent drug resistance. Indeed, the number of multi-drug resistant TB (MDR-TB) cases notified by the 27 high burden countries is on the increase and reached 600,000 cases globally in 2011.5 This increase in number of MDR-TB cases requires an investigation into the effectiveness of current TB treatment regimens as well their dosing frequencies. Two systematic reviews3,6 undertaken to look into this were limited by methodology, with neither looking at all outcome categories or stratifying treatment intensity (daily versus intermittent) by rifampicin use in the IP alone versus both phases. Conclusions thus remain uncertain, and given that the basis of the 2010 WHO recommendations was the last review in 2009,3 and there are now more studies that have been published, we set out to compare the effectiveness of WHO category 1 TB treatment regimens containing EHRZ in the IP offered either daily (D) throughout or intermittently (I) two-three times per week throughout, stratified according to use of rifampicin in either IP alone or in both phases. We also used a more robust methodology for the meta-analysis of proportions.7

Methodology

Search Strategy

Three electronic databases — Embase, PubMed, and Cochrane CENTRAL — were searched for studies on treatment of active pulmonary tuberculosis (TB). The search for studies was restricted to studies published in English spanning from 1965 to 2013. The following search terms were used: (Tuberculosis OR Koch’s disease) AND (Therapeutics OR Therapeutic OR Therapy) AND (Treatment outcome OR Effectiveness OR Efficacy OR Failure OR Drug resistance) AND (Isoniazid OR Pyrazinamide OR Rifampicin OR Ethambutol). We identified further studies through searching related citations of identified original articles on PubMed. A detailed search string is provided in the supplementary material.

Study Selection

We conducted a three staged study selection that was done independently by two investigators (figure 1). The selection considered article titles, then abstracts, and finally full text articles, after which comparisons were made and resolution of disagreements reached through discussion and consensus by a third investigator. The selection included original articles of studies that reported treatment outcomes of HIV negative, new drug susceptible, smear positive pulmonary TB patients who were bacteriologically confirmed by sputum smear or culture at both the start and end of the treatment period. Only TB patients treated with WHO Category 1 standard 5–8 months duration regimens containing 2 months of EHRZ in the IP were included. We excluded studies with smear negative TB, extra-pulmonary TB, unconfirmed TB, HIV sero-positive patients, and studies with patients treated with regimens other than WHO Category 1 standard regimens (without EHRZ in IP) or regimens with rifapentine and infrequent therapy such as those with once weekly dosing. We stratified our analyses by regimens that used rifampicin in both phases versus regimens that used rifampicin only in the IP.

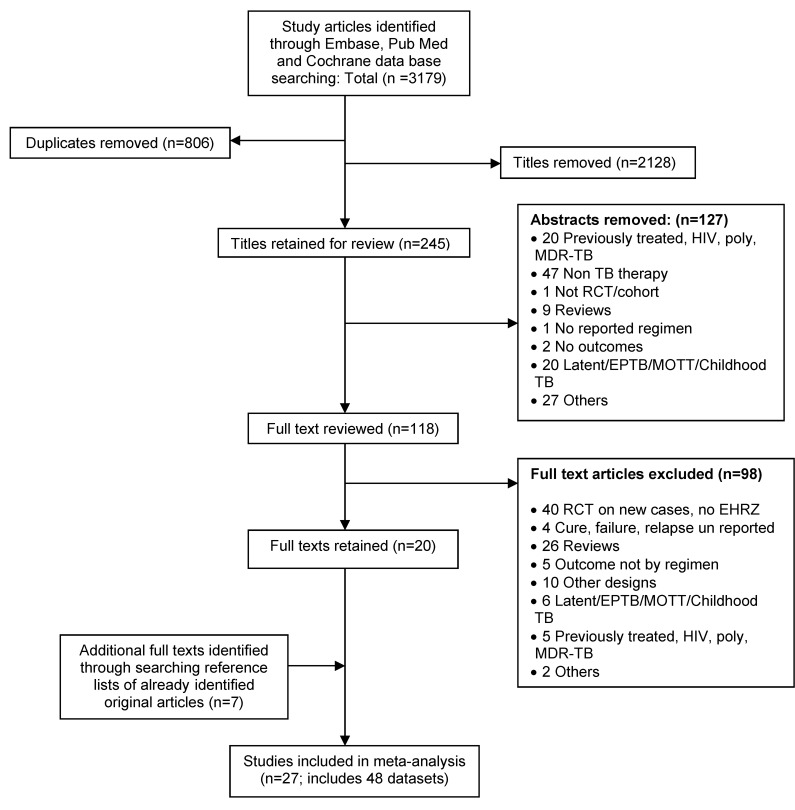

Figure 1.

Summary of literature search and selection of studies.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two investigators working independently reviewed all identified and selected studies while resolving data differences through discussion and reaching consensus using a third investigator. We then extracted data from selected studies that met the study criteria on patient population and characteristics, number of patients started on treatment, pre- and post-treatment bacteriological results (smear and culture), treatment regimens, supervision of treatment (through directly observed therapy [DOT]) and treatment outcomes. The treatment outcomes of interest were in four categories: treatment success, failed, relapsed, and defaulted (see definitions below).

Quality of study information was ensured by assessing all included studies using a standardized quality assessment form. The quality assessment scheme was modified from that suggested by Hoy et al,8 which is a validated quality assessment checklist (also see supplementary material online). Once assessed, each study was awarded a univariate summary score from all parameters assessed. The total score for each study was then applied to assign weights for each study included in this meta-analysis. If a study contributed more than one dataset, each had the same quality score assigned. This model of meta-analysis does not assume that quality information quantifies either the magnitude or the direction of bias. The ranking of the studies by quality is used to compute a synthetic bias variance that then increases uncertainty around estimates for lower ranked studies.9

Outcome Definitions and Exclusions

TB case and treatment outcome definitions of the WHO were used to classify TB cases and to determine treatment outcomes.5,10–12 A new case was defined as a TB patient who had never been on TB treatment before or had ever been on TB treatment but for less than one month. A pulmonary TB case was defined as a TB patient with TB disease involving the lung parenchyma. Regarding treatment outcomes, successfully treated was defined as a combination of completed and cured TB patients. Cure was defined as a patient who was initially bacteriologically positive and who was bacteriologically negative in the last months of treatment and on at least one previous occasion while completed treatment was defined as a patient who completed the standard TB treatment but lacks bacteriological results at the end of treatment. For purposes of this study, a failure was defined as a TB patient who remains or becomes bacteriologically positive at 5 or more months of standard TB treatment or who dies during TB treatment. Relapse was defined as a TB patient who becomes bacteriologically positive after being declared cured at end of TB treatment while a defaulter/loss to follow-up is a TB patient who interrupted TB treatment for 2 or more months after being on treatment for more than one month. Patients who could not be categorized as cured, completed, failed, relapsed, or defaulted based on the above definitions, or if they were transferred to another reporting unit (health facility or district) during treatment or for whom treatment outcome was unknown, were excluded from analysis.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

In all the studies, multi-category proportions of successfully treated, failure, relapse, and default/loss to follow-up were computed as separate categories and pooled simultaneously. Analyses were done separately for regimens with rifampicin in all phases versus rifampicin in IP only. The primary outcome of interest was the proportions of these four outcomes in those receiving completely intermittent (I/I) or completely daily (D/D) treatment. The secondary outcomes were those for mixed regimens that used daily therapy in one phase and intermittent in the other or regimens that used rifampicin only in the IP.

We used the quality effects model13 to pool the categorical proportions and report the overall pooled estimate of the various outcome categories. We chose the quality effects model over the conventional random effects model based on the fact that the model incorporates quality of studies in the analysis of the overall intervention efficacy,13 thereby reducing variance of the pooled estimator.9 This model uses a synthetic bias variance to adjust inverse variance weights and achieves an estimator variance that is smaller than that of the random effects estimator. This synthetic bias variance is computed through the quality assessment and, regardless of how subjective the assessment is, so long as it has some information value, the estimator variance decreases. Furthermore, this model also overcomes the coverage problems seen with the random effects estimator for which corrections have been attempted.14 We, nevertheless, report conventional results (random effects and fixed effects models, see supplementary material) for comparison. All analyses utilized MetaXL version 2.0 (Epigear International Pty Ltd, Brisbane, Australia; www.epigear.com). We preferred MetaXL in this analysis, since it has both an improved methodology of meta-analysis of multi-category prevalence7 as well as the ability to execute bias adjusted analyses. By bias adjustment, we mean that weighting done under this model allows the results of the “big” studies (with less bias) to make a greater contribution to the pooled effect, thus decreasing overall bias of the estimator. In computing the pooled proportions using MetaXL, the double arcsine square root transformation was used to stabilize variance of the proportion and results back transformed for reporting 95% confidence intervals around pooled estimates were computed as previously reported.7, 5

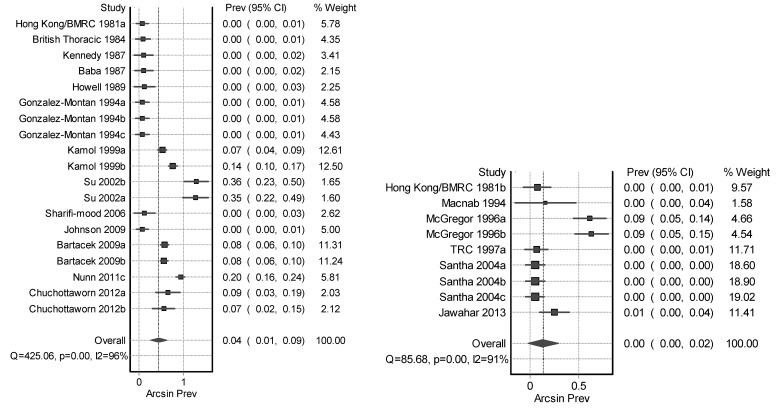

We determined whether heterogeneity (clinical, statistical, or methodological) existed among studies that we included in the meta-analysis by drawing up forest plots (figures 2 and 3) to graphically present individual and pooled estimates as well as using the heterogeneity statistics; the Cochran’s Q and I2 statistic, which examine the percentage variation across studies due to heterogeneity.15 A sensitivity analysis by altering various study selection criteria including study size, year of study, monitoring of therapy, and country of origin were computed. We also compared results across different meta-analysis models for outcome comparison. In addition, we looked for publication bias through Doi and funnel plots15–17 (figures 4 and 5).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of daily* (left) and intermittent* (right) regimen success (Rifampicin throughout).

*These subjects had either the intermittent or daily therapy with Rifampicin throughout both phases of TB therapy. Horizontal lines represent 95% CI for the studies, box size depicts the study weight and diamond depicts the confidence interval of the pooled estimate.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of daily* (left) and intermittent* (right) regimen defaulters (Rifampicin throughout).

*These subjects had either the intermittent or daily therapy with Rifampicin throughout both phases of TB therapy. Horizontal lines represent 95% CI for the studies, box size depicts the study weight and diamond depicts the confidence interval of the pooled estimate.

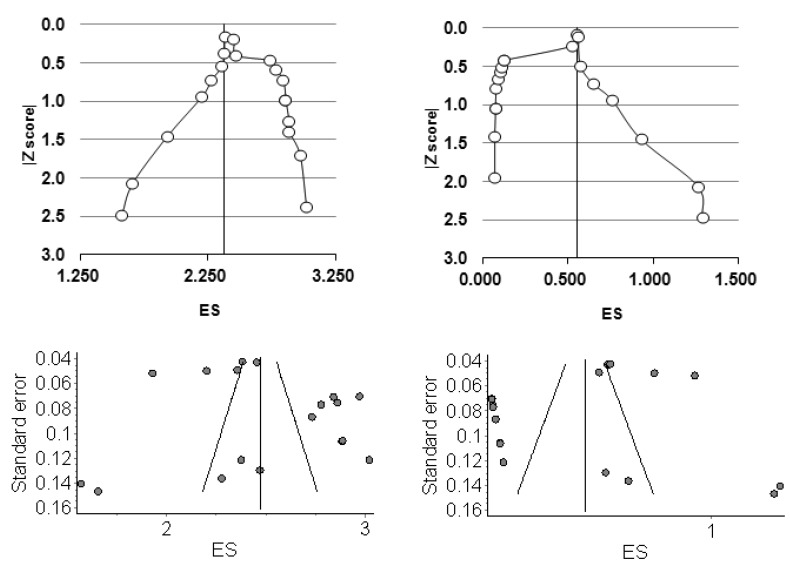

Figure 4.

Doi plots (top) and funnel plots (bottom) for D/D regimens among success (left) and defaulter (right) proportions on the double arcsine square root scale (ES).

Figure 5.

Doi plots (top) and funnel plots (bottom) for the I/I regimens among success (left) and default (right) proportions on the double arcsine square root scale (ES).

Results

Description of the Studies Included

We identified 3,179 studies from the three electronic databases, of which 806 were duplicates and 2,128 were excluded by title (figure 1). We, therefore, retained 245 titles for abstract review, from which 127 abstracts were excluded, leaving 118 abstracts for review. Upon review of these abstracts as full text, 98 were excluded, thereby leaving 20 studies to be included in the meta-analysis. An additional 7 studies were identified through a related citation search of already identified original articles, thereby obtaining a total of 27 studies that were included in this meta-analysis.

We obtained 48 data sets from all included studies with 10,624 participants that were enrolled across these studies. Out of the 10,624 participants, 7,611 were on completely daily treatment (28 datasets) and 3,013 on completely intermittent therapy (9 datasets). Of the 10,624 participants, 8,336 were on regimens that contained rifampicin in both IP and CP (28 datasets), while 2,228 were on regimens that had rifampicin in IP only (9 datasets). All included studies involved HIV sero-negative adults (except 4 studies; first with 6, second with 115, third with 77, and the fourth with 32 HIV sero-positive participants18–21) with smear positive pulmonary TB (except in one study, 67 out of 198 patients were smear negative22). Moreover, in one study, a third of the 1,240 patients included were previously treated.23 In all these scenarios, ineligible patients could not be excluded by both regimen type and treatment outcome. Again, instead of rifampicin (R), rifabutin was used in two of the studies included with a total of 491 participants.24,25 Treatment doses were fully supervised in eleven studies,19–21,23,26–32 supervised as well as self-administered in nine studies,22,25,33–38 and only self-administered in two,39,40 while treatment modality was unspecified in five studies.18,24,41–43

Pooled Results

Primary outcome – same intensity of dosing throughout

Intermittent regimens

Rifampicin was administered intermittently (I/I) in both phases (twice to thrice weekly) in nine datasets; all of these datasets had a CP of 4 months.23,24,26,28,30,44 The overall treatment success with this intermittent regimen was 88% (95% CI, 81–92), failure and relapse rates were 5% (95% CI, 2–9) versus 7% (95% CI, 3–11), and default rate was 0% (95% CI, 0–2) (table 1).

Table 1.

Tuberculosis treatment outcomes (37 datasets from 18 studies)

| Regimen | Success | Failed | Relapsed | Defaulted | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rifampicin throughout | |||||

| Intermittent* (n=9 datasets) | 0.88 (0.81–0.92) | 0.05 (0.02–0.09) | 0.07 (0.03–0.11) | 0.00 (0.00–0.02) | 1 |

| Daily* (n=19 datasets) | 0.90 (0.84–0.95) | 0.04 (0.01–0.08) | 0.01 (0.00–0.03) | 0.05 (0.01–0.09) | 1 |

| Overall | 0.91 (0.84–0.95) | 0.03 (0.01–0.08) | 0.01 (0.00–0.03) | 0.04 (0.01–0.09) | 1 |

| Rifampicin only in IP | |||||

| Daily* (n=9 datasets) | 0.75 (0.57–0.91) | 0.05(0.00–0.15) | 0.02 (0.00–0.09) | 0.15 (0.02–0.30) | 1 |

These subjects had either the intermittent or daily therapy throughout (both phases)

Daily regimens

Rifampicin was administered daily (D/D) in both phases in 19 datasets.18,19,21,22,25–27,29,36,39–41,43 The overall treatment success was 90% (95% CI, 84–95) with failure and relapse rates of 4% (95% CI, 1–8) and 1% (95% CI, 0–3), but default rates of 5% (95% CI, 1–9).

Secondary outcomes

Mixed regimens

There were eight datasets20,31,33,34,45 with daily/intermittent (D/I) therapy that used rifampicin throughout, and they achieved 91% (95% CI, 86–96) success, 3% (95% CI, 1–7) failure, 4% (95% CI, 1–8) relapse, and only 1% (95% CI, 0–3) default.

Rifampicin Only in IP

There were nine datasets reporting results of D/D regimens.19,35,38,42,44 These regimens had an overall treatment success of 75% (95% CI, 57–91). The failure and relapse rates were 5% (95% CI, 0–15) and 2% (95% CI, 0–9), but the default rates were 15% (95% CI, 2–30).

There were two studies’ of I/D administration of 6 months.19,37 The overall treatment success among these regimens having no rifampicin in the CP was 81% (95% CI, 31–100), with failure and relapse rates of 8% (95% CI, 0–47) versus 5% (95% CI, 0–42) and default rate of 3% (95% CI, 0–36).

There was one study of a D/I therapy that did not use rifampicin in the CP and of 6 months duration.45 It reported a treatment success of 74% (95% CI, 64–84), with failure and relapse rates of 26% (95% CI, 16–36) versus 0% (95% CI, 0–2) and default rate of 0% (95% CI, 0–2) (table 1).

Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis was done for the D/D studies by altering selection criteria such as regimen type, treatment duration, dosing frequency, treatment outcome and comparing treatment outcome results across different meta-analysis models. More still, comparisons were made by examining treatment outcomes in relation to study size, year of publication, country where study was conducted as well as whether therapy was monitored or not. No significant differences were observed across treatment outcomes under both quality effect and fixed effect (IVhet) meta-analysis models. For instance, under a quality effects model, the D/D group with rifampicin administered throughout, treatment success among bigger and smaller studies were 90% (95% CI, 82–96) versus 91% (95% CI, 81–99). Again, in the D/D group with rifampicin administered throughout, the treatment success was comparable among studies where therapy were fully supervised (90%) (95% CI, 74–1.00) and not fully/unsupervised (90%) (95% CI, 83–95) (table 2).

Table 2.

Sensitivity analysis based on the largest group of datasets (daily throughout and rifampicin throughout)

| Criteria | Cut off | Datasets | Success | Failed | Relapsed | Defaulted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study size | Small <166 | 9 | 0.91 (0.81–0.99) | 0.03 (0.00–0.10) | 0.02 (0.00–0.08) | 0.03 (0.00–0.10) |

| Big ≥166 | 10 | 0.90 (0.82–0.96) | 0.04 (0.00–0.08) | 0.01 (0.00–0.03) | 0.05 (0.01–0.11) | |

|

| ||||||

| Year of publication | Before 1999 | 8 | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | 0.01 (0.00–0.02) | 0.01 (0.01–0.02) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) |

| 1999 and after | 11 | 0.84 (0.76–0.91) | 0.05 (0.01–0.10) | 0.01 (0.00–0.03) | 0.09 (0.04–0.15) | |

|

| ||||||

| Country | African or African with other settings purely non-African | 4 | 0.92 (0.84–0.98) | 0.02 (0.00–0.07) | 0.01 (0.00–0.05) | 0.04 (0.00–0.10) |

| 15 | 0.89 (0.80–0.97) | 0.04 (0.00–0.10) | 0.01 (0.00–0.04) | 0.05 (0.00–0.12) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Monitored therapy | Fully | 6 | 0.90 (0.74–1.00) | 0.04 (0.00–0.15) | 0.02 (0.00–0.10) | 0.04 (0.00–0.16) |

| Partly/not at all/unspecified | 13 | 0.90 (0.83–0.95) | 0.04 (0.00–0.08) | 0.01 (0.00–0.03) | 0.05 (0.01–0.10) | |

Publication Bias

We evaluated publication bias through visual inspection of funnel plots based on standard error (figures 4 and 5). We observed that they were not interpretable, which is in keeping with the observation that visual inspection of funnel plots can misrepresent bias and be misleading as well.15,17,46 We further examined publication bias using the Doi plot. The Doi plots for treatment success for D/D regimens were more or less symmetrical suggesting no gross bias (figure 4). For I/I regimens, there was gross asymmetry for both success and default proportions with possible heterogeneity across the studies favoring more success but more default as well, and thus, low default proportions with these regimens are unlikely to have been influenced by under-reporting (figures 4 and 5).

Discussion

In this study of 27 studies involving EHRZ in the initial phase of TB treatment, administration of therapy intermittently (I/I) twice or three times a week rather than daily (D/D) was associated with similar treatment outcomes of success and failure (table 1, and figures 2 and 3). The most important finding of this meta-analysis, however, was that there was a trade-off between default and relapse rates between D/D and I/I regimens (table 1). Default rates were low with the I/I regimens, and these finding concur with that reported by individual reports of intermittent WHO category 1 TB treatment regimen involving EHRZ.44,47,48 Thus, the important issue in fully intermittent regimens is those of better treatment compliance and adherence rather than of regimen efficacy. Indeed, intermittent regimens have been found to offer practical solutions to high pill burdens, inconvenience, and intractable drug adverse reactions associated with daily TB therapies.1,49

The trade-off, however, is with increase in relapse with I/I that is matched by the increase in default with D/D. The D/I regimen had a slightly lower default but relapse was still higher. This finding is supported by a review6 that examined intermittent therapy of thrice weekly versus daily therapy in a single randomized trial26 where intermittent therapy was administered and recurrence was increased 4 fold with intermittent therapy (non-significant) compared to the daily group, but no conclusions were drawn. These observed differences in treatment relapse versus default rates were not reported by Menzies et al3 because they used pooled cumulative incidences, adjusted incidence rate ratios, and risk differences only on outcomes of failure, relapse, and acquired drug resistance and did not separate out rifampicin duration and intermittency of therapy. In our case, we used proportions of successfully treated, failure, relapse, and default as separate categories and pooled them simultaneously. Analyses were also done separately for regimens with rifampicin in all phases versus rifampicin in IP only. We believe that these results point towards the fact that I/I regimens possibly require a longer duration than 6 months to prevent relapses, since a systematic review by Chang et al50 suggests that extending treatment of 6-month regimens may reduce relapse of TB. The intermediate option, the D/I regimens, do not solve the relapse issue seen with I/I regimens.

Twelve studies had no rifampicin in the CP and included two studies19,37 involving I/D, nine studies19,35,38,42,44 using D/D, and one study using D/I.45 These regimens with shorter durations of rifampicin usage were found by Menzies and colleagues3 to have high unfavorable treatment outcomes. Menzies et al report a pooled event rate of 1.8 (CI, 0.2–3.3) versus 0.4 (CI, 0.1–0.7) for failure, 16 (CI, 11.1–20.9) versus 3.8 (CI, 2.9–4.7) for relapse, and 0.8 (CI, 0–1.6) versus 0.4 (CI, 0.1–0.7) for acquired drug resistance, respectively when comparing 2 months with 6 months of rifampicin.3 Our data, however, suggest that if we compare D/D to D/D regimens with long and short rifampicin treatment, what differs is default rates −5% (CI, 1–10) versus 15% (CI, 2–30). Thus, these regimens are unsuccessful, because subjects default rather than relapse. Menzies et al51 were not able to demonstrate this, because they did not separate out duration of rifampicin from intensity (frequency) of therapy. These observed differences for short duration rifampicin based regimens which could therefore possibly be explained by increased default possibly due to ethambutol related toxicity.

There were some studies that appeared to be outliers in the forest plot (figure 2 and 3), but none of the studies gave any details. McGregor et al24 report that 24 defaulted, but no reasons were given. Su et al39 reported that only 51 out of 105 patients enrolled into the study completed the full course. Analysis of the study report indicates a possible poor patient management protocol that led to a high attrition rate, and 33 defaulted. In addition to defaulters, 51.4% of the study participants never completed. Similarly, Nunn et al19 appeared as an outlier, because 237 patients defaulted, but again no reason was given, except that they mention default rates were similar across all three regimens they compared.

This meta-analysis had a number of limitations. Most studies that reported drug resistance did not uniformly provide elaborate information among their findings. The few that attempted to do this did not provide information in a standard manner to facilitate useful analysis that could yield generalizable results. Therefore, this study did not look at the effect of primary drug resistance on the outcomes; neither did it look at acquired drug resistance. More still, although three trials incorporated in this meta-analysis included a few HIV sero-positive TB patients, this study was unable to determine their impact on the overall results. However, in a separate study involving HIV infected TB patients, intermittent TB therapy with rifampicin based regimens alone on a twice weekly dosing schedule in the initial phase but not in the continuation phase, was associated with high risk of relapses and an increased risk of acquired rifampicin resistance.52 Such studies were, however, given a lower quality score, which mitigates this to some extent. Another major limitation was the fact that there were fewer studies done involving completely intermittent therapy, thereby limiting the number of studies available for this analysis. However, follow up was satisfactory in all studies, except in three where the follow-up period was less than one year, but this finding is not expected to affect study results, since the majority of studies had more than one year of follow-up period. Again, these studies were given a lower quality score.

Conclusion

In conclusion, poor treatment compliance and adherence due to longer duration of therapy is linked to poor outcomes,53,54 and thus, to ensure improved treatment efficacy and adherence as well as compliance, we believe that there is a need to switch to treatment regimens containing rifampicin in both phases that are offered I/I while ensuring directly observed therapy among HIV sero-negative TB patients, since they are associated with similar treatment success and failure and low default rates. However, relapse rates are higher, and it is possible that this could be mitigated by a longer duration of more than 6 months of therapy, but this needs to be further investigated urgently by future studies.

Supplementary Material

Table S1.

TB treatment outcomes – IVhet model (fixed effects with over dispersion correction).

| Regimen | Success | Failed | Relapsed | Defaulted | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rifampicin throughout | |||||

| Intermittent (n=9) | 0.87 (0.80–0.91) | 0.06 (0.02–0.10) | 0.07 (0.03–0.11) | 0.00 (0.00–0.02) | 1 |

| Daily (n=19) | 0.89 (0.82–0.95) | 0.04 (0.00–0.08) | 0.01 (0.00–0.03) | 0.05 (0.01–0.10) | 1 |

| Overall | 0.90 (0.82–0.95) | 0.04 (0.00–0.08) | 0.01 (0.00–0.03) | 0.05 (0.01–0.10) | 1 |

| Rifampicin only in IP | |||||

| Daily (n=9) | 0.75 (0.55–0.92) | 0.05(0.00–0.17) | 0.02 (0.00–0.11) | 0.14(0.01–0.30) | 1 |

Table S2.

TB treatment outcomes – random effects model (underestimates the statistical error)

| Regimen | Success | Failed | Relapsed | Defaulted | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rifampicin throughout | |||||

| Intermittent (n=9) | 0.89 (0.83–0.92) | 0.04 (0.02–0.08) | 0.06 (0.03–0.09) | 0.01 (0.00–0.03) | 1 |

| Daily (n=19) | 0.91 (0.85–0.95) | 0.03 (0.01–0.06) | 0.01 (0.00–0.03) | 0.04 (0.01–0.08) | 1 |

| Overall | 0.92 (0.85–0.95) | 0.03 (0.01–0.06) | 0.01 (0.00–0.03) | 0.04 (0.01–0.08) | 1 |

| Rifampicin only in IP | |||||

| Daily (n=9) | 0.77 (0.61–0.90) | 0.04(0.00–0.13) | 0.01 (0.00–0.07) | 0.14 (0.04–0.29) | 1 |

Table S3.

Data Abstraction table A: Study methodology, regimen type and Treatment supervision type.

| References | Country of study | Study design | Inclusion/exclusion criteria | Patient characteristics | Regimen type and frequency | Supervision of treatment (DOT) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | Taiwan | Randomised clinical trial of two 6 months regimens; one group to fixed dose combination (FDCs) (Rifater/Rifinah) with EHRZ, second group to separate four drugs of EHRZ | Newly diagnosed smear or culture positive pulmonary tuberculosis and with no history of previous anti-tuberculosis treatment. Ineligible were smear negative TB patients and previously treated. | 93 patients were males and 12 were females. Mean age not given. All recruited from an outpatient chest clinic | 2EHRZ/4RHE | Self-administered - FDC | Daily dosages with FDCs consisting of 2Rifater +EMB and 4 of Rifanah +EMB |

| 2EHRZ/4RHE | Self-administered–Loose tabs | Separate formulations of EHRZ | |||||

| [2] | Iran | Experimental clinical trial, with patients randomised to 2EHRZ/2RH and 2EHRZ/4RH | Adults with Newly diagnosed sputum smear positive pulmonary TB, with no cavitation and no abnormality in more than one lobe on plain CXR were eligible while those with concomitant Hypertension, DM, Epilepsy, immunodeficiency and serious forms of EPTB were excluded. | There were 28 females with mean age of 15 years and 39 males with mean age of 52 years. 13 patients were from Afghan and rest from Iran recruited from a health center | 2EHRZ/4RH | All drugs were administered under DOT as daily Single doses | |

| All drugs were administered under DOT as daily Single doses | |||||||

| [3] | Africa and Asia | Multi-centre randomised controlled trial where allocation sequence was independently computer generated and supplied to participating centres in sealed envelopes. | Patients with at least two positive sputum smears for AFFBs, with no previous anti-TB chemotherapy for more than one month, with accessible addresses and those willing to undergo HIV testing were eligible. Ineligible were pregnant women, EPTB and psychiatric patients, the ill and those with concomitant disease (DM, Epilepsy, liver diseases, nephritis, peripheral neuritis, blood disorders, alcoholism) and patients with confirmed Rifampicin resistance | Pre-treatment characteristics were broadly similar and median age was 28 years with 66% of patients being males and 13% of 881 tested being HIV positive. All recruited from participating treatment centers | 2EHRZ/6EH | Facility DOT for the first 2 months, then family or community based DOT in continuation phase. | |

| 2[EHRZ]3/6EH | |||||||

| 2EHRZ/4RH | |||||||

| [4] | South Africa | Prospective controlled clinical trial study comparing Rifater (RHZ) with 2EHRZ/4RH (given 5 days a week for 130 doses) | Adults in Cape town Municipal area with first episode of pulmonary TB diagnosed by chest radiograph and a positive culture where studied while those with additional non-tuberculous pathology as were pregnant women were excluded. | Non-white patients aged over 15 years. No further details on patient characteristics | 3[EHRZ]5/3.5[RH]5 | DOT offered by supervisors at clinic/work and anti-TB drugs given 5 days a week for 130 doses | Study terminated prematurely when EMB became unavailable |

| [5] | Africa, Asia and Latin America | Multi-centre open label non-inferiority randomized controlled trial conducted between 2003 and 2008 in 11 centres in Africa, Asia and Latin America. 798 Patients randomised to 8 weeks of EHRZ and 18 weeks of [RH]3 as FDCs and 787 patients to separate drugs | 18 years and above with Newly diagnosed smear positive pulmonary TB with two by sputum smear on direct smear microscopy and with either no history of previous anti-tuberculosis treatment or for less than 4 weeks for the current episode, with accessible address and has informed consent. Ineligible were pregnant women, EPTB and psychiatric patients, the ill and those with concomitant disease (DM, Epilepsy, liver diseases, nephritis, peripheral neuritis, blood disorders, alcoholism) and patients with confirmed Rifampicin resistance | There were 393 males on FDC and 387 on separate drugs and 198 females on FDC and 192 on separate drugs. Mean age for FDC group was 33.8 and 34.2 for loose formulations. 39 on FDC and 38 patients on separate drugs were HIV positive while 330 on FDC and 317 on loose drugs never smoked. | 2EHRZ/4[RH]3 (FDC) | DOT | |

| 2EHRZ/4[RH]3 (Separate drugs) | |||||||

| [6] | Thailand | Randomized controlled trial where 837 patients were assigned to receive TB treatment -2EHRZ/4RH by DOT or self-administration on basis of daily drug supply in 15 study sites | TB patients with a positive sputum smear for AFBs. Ineligible were patients less than 15 years old, patients with previous history of treatment for TB for > 1 month, known allergy to any of the drugs in treatment regimen, pregnancy, hepatic or renal failure patients. | Mean age was for DOT and self-supervised was 45±17. The male: female ratio was 2.6:1 for DOT and 2.9:1 for self-supervised. Unemployed on DOT were 17 and 20 for self-supervised. All recruited from Zonal Government TB centers and hospitals TB centres | 2EHRZ/4RH | DOT | |

| 2EHRZ/4RH | Self-administered | ||||||

| [7] | Brazil, Philippines and Uganda | Multi-centre phase 3 randomised open label, two sided equivalence trial | HIV uninfected adults with sputum AFB smear positive or negative, non cavitary, drug susceptible TB, with relatively normal hematologic, renal and hepatic function who converted to negative after 2 months of treatment | 120 were males, mean age for study participants was 30.3, average weight 55.2kg, BMI 20.3kg/m2 | 2EHRZ/4RH | DOT Daily for at least 5 days a week | Study was stopped due to high relapse rate and all waiting patients were treated with 6 months regimen |

| [8] | Indonesia | Prospective randomised trial were patients were randomly allocated to the NTP regimen with separate TB drugs and FDC regimen @ with 4 drugs in blister packs | New smear positive patients with body weight between 33kg and 50kg excluded; previously treated, smear negative and body weight < 30kg | There were 96 males and 66 females on loose drugs regimen and 119 males and 79 females on FDC regimen recruited from health center clinics | 2EHRZ/[4RH]3 | DOT | NTP regimen single drug molecules |

| 2EHRZ/[4RH]3 | DOT | FDC regimen (combined formulation) | |||||

| [9] | Argentina, Brazil and Thailand | Multi-centre open label, active controlled randomized, parallel group comparative study to assess efficacy, tolerability and toxicity of regimens: 2EHRZ/4RH, 2Rifabutin150EHZ/4R150H and 2Rifabutin300EHZ/4R300H | HIV negative patients with previously untreated TB that was radiolographically active and bacteriogically confirmed by culture of at least two sputum samples attending outpatient clinic with willingness to participate were included in study. Excluded patients with depressed haematopoietic function (WBC <4000 cells/ml and platelets of < 150,000 cells/ml), patients with severe hepatic impairment, advanced renal dysfunction, malignancies, immunodepressant therapy and pregnancy. |

63 females and 112 males were on rifampicin and 59 females and 115 males were on rifabutin. The median age for rifampicin group was 29 with range of 15–69 years and was the same for rifabutin but with a range of 15–67. 157 from Argentina, 162 from Brazil, 201 from Thailand. 53% had moderately advanced while 41% had advanced disease | 2EHRZ/4RH | DOT for 1st month only | |

| 2Rifabutin150EHZ/4R150H | |||||||

| 2Rifabutin300EHZ/4R300H | |||||||

| [10] | Pakistan | Interventional study comparing DOT by health worker and a family member and self-administered therapy | Newly diagnosed AFB smear positive adult (age 12 years and above) pulmonary TB. Ineligible were patients < 12 years, EPTB, COPD, lung malignancy, decompensated cirrhosis, chronic renal disease or stroke and with suspected MDR-TB. | Recruited from a hospital setting. Baseline characteristics not given | 2EHRZ/4EH | DOT by Health worker | |

| 2EHRZ/4EH | DOT by family member | ||||||

| 2EHRZ/4EH | Self - administration | ||||||

| [11] | Thailand | Prospective open label randomized study with newly diagnosed pulmonary tuberculosis patients randomized to receive six month once daily VS twice a day (split drugs) regimen | Newly diagnosed smear positive pulmonary patients with at least one positive sputum smear for AFB who had never received or received anti-tuberculosis treatment for less than one month with compatible CXR, aged over 20 years, non-pregnant, willing to participate. Excluded were chronic cardiac, lung diseases, hepatitis with liver enzymes raised more than three times, renal disease with greater than 2.0 mg serum creatinine, neurological diseases like dementia and HIV. | There 44 males in group A and 41 in group B, Females were 17 in group A and 20 in B. Age was 37.1±11.4 in A and 37.2±10.9 in B. In A were 11 and B 9 diabetics. Overall, weight was 51.8±9.1kg in A and 51.9±9.9 in B. | 2EHRZ/4RH | DOT by family member | Drugs given once daily RH given in morning and ZE given at bed time |

| 2EHRZ/4RH | DOT by family member | ||||||

| [12] | Britain | Controlled trial of short course chemotherapy in which two 6 month regimens were compared with a control of 9 month where patients were followed up to 36 months | Patients with culture positive pulmonary TB. | All patients had a positive culture on admission, with 58% having a positive smear too. No other baselines are given. | 2EHRZ/4RH | Self-administered | |

| [13] | Egypt, India, Pakistan, Philippines and Thailand | Prospective open randomized multi-centre, multinational study conducted in 26 centres and included 1159 patients randomized to receive daily FDCs or single ant-TB drugs (ST) regimens @ containing 2EHRZ/4RH | Aged 15 years and over with newly diagnosed smear positive pulmonary patients with at least two by sputum smear positive for tubercle bacilli on direct smear microscopy, postero-anterior CXR consistent with PTB, as determined by the clinician and with for less than 4 weeks of previous anti-tuberculosis treatment, with accessible address and has informed consent and willingness to follow protocol. Ineligible were patients < 30 kg, hypersensitivity to used anti-TB drugs, patients with drug induced hepatitis, liver or renal diseases, gout, tuberculous meningitis, (immunosuppressive) treatments (e.g. Corticosteroid) or drug abuse and alcoholism. Any condition that can prove fatal during treatment except HIV. | Age for FDC was 37.4±15.3 and 36.4±14.6 for single tablets. Body weight was 50.3±15 for FDC group and 49.9±10.3kg for single tablets. 18.7% under FDC and 19.4% in single tablet group were previously treated. | 2EHRZ/4RH | Unspecified, on FDC | Although HIV infection was one of the exclusion criteria for the study, six HIV positive patients (one in the 4-FDC group, five in the ST group) were included by investigators |

| 2EHRZ/4RH | Unspecified, on ST | ||||||

| [14] | India | Controlled clinical trial among patients who attended chest clinics of Tuberculosis Research Centre and were treated them with intermittent regimen in initial phase: 2[EHRZ]3/6[EH] | Patients aged 12 years or more who attended chest clinics of Tuberculosis Research Centre and had at least 2 positive sputum smears for AFB who had not received previous chemotherapy for 1 month or more. Excluded patients with severe visual defects other than refractory error | Recruited from TRC chest clinics. 70% were males, mean age was 31.4 years (range 27.4–74.2). Smear grading of 2+ or more was in 70% of patients while a culture grade of 3+ was in 80%. Full susceptibility to both H and R was in 91% of patients, H and HR resistance was 8.4% and 0.9% respectively. | 2[EHRZ]3/6[EH] | DOT in intensive phase and 1st dose under DOT plus six doses of self-administration per week in continuation phase | |

| [15] | India | Controlled randomized trials of oral short course TB regimens: 2EHRZ/6EH, 2[EHRZ]2/4[RH E]2 | OPD patients with respiratory symptoms, aged 12 years or more, free of visual defects other than refractory error with at least two sputum smears positive for AFBs were randomly allocated to regimens of interest irrespective of previous anti-TB chemotherapy | 67% of the patients were males with mean age of 30.3 years (range 12–62 years) with mean weight of 39.9kg (range 15–60kg). All patients had a poor socio-economic background. Smear positivity was similar in all regimens. | 2EHRZ/6EH | self-administration | |

| 2[EHRZ]2/4[RH E]2 | DOT and self-administration | ||||||

| [16] | India | Open label randomized controlled trial comparing intermittent regimens | Newly diagnosed pulmonary TB patients with at least 2 positive sputum cultures and are residents of the study area, willing to test for HIV and ready for supervised outpatient treatment and home visits. Ineligible were those with previous history of TB treatment of >30 days or weighing less than 30kg, pregnant, lactating, those with diabetes, hypertension, epilepsy, EPTB and HIV | 74% were males and 26% females. Patients aged <40 years were 120 and ≥40 were 45. Mean age was 43 years (range 30.2–59,1), average weight 43kg, all were smear positive, 84% susceptible to HRE, non was resistant to HE. 20% were resistant to R. | 2[EHRZ]3/4[RHE]3 | DOT | |

| [17] | Pakistan | Randomized controlled trial of short course chemotherapy comparing direct observation of treatment (DOT) by family member, health worker and self-administration | Newly diagnosed sputum positive pulmonary TB patients living in the study area. Ineligible were those with previous history of TB treatment. Patients from WHO demonstration sites were excluded. | Males constituted 54% of patients on HW-DOT, 52% on Family DOT and 48% on self-administration. Urban dwellers on HW-DOT were 37%, Family DOT-51%, Self-administration 69%. Age range was 15 to ≥55 years | 2EHRZ/6EH | DOT | By Health worker |

| 2EHRZ/6EH | DOT | By family member | |||||

| 2EHRZ/6EH | Self-administration | At home | |||||

| [18] | Indonesia | Comparative study investigating relapse rates among patients randomly allocated and treated with FDC and loose TB drugs | Newly diagnosed sputum positive pulmonary TB adult patients. Ineligible were smear negative and extra-pulmonary TB patients. | Mean age was 36.5 for those on loose drugs with males constituting 59.1% and 37.7 years for those on FDC with 60.2% being males. All were recruited from 15 health center clinics | 2EHRZ/3[RH]3 | DOT and self-administration | FDC |

| 2EHRZ/3[RH]3 | DOT and self-administration | Loose drugs | |||||

| [19] | South Africa | Randomised trial of intermittent regimens | Newly diagnosed pulmonary TB patients aged 15 years or older suitable for twice weekly supervised ambulatory treatment. Excluded smear negative, patients with resistance to 2 or more TB drugs and those with advanced TB, alcoholics and those in poor general conditions or having concomitant diseases including pregnant women. | The male:female ratio was 4.5:1 and mean age 36.7 years (SD 10.3, median 34, range 15–74). Recruitment was from 2 TB hospitals and major urban clinics in Pretoria. | 2EHRZ/4[RHZ]2 | DOT | |

| 2EHRZ/4[EHZ]2 | DOT | ||||||

| [20] | India | Controlled clinical trial among patients who attended chest clinics and were randomised to 3 intermittent regimen | Patients aged 12 years or more who attended chest clinics and had at least 2 positive sputum smears for AFB/cultures and were willing to clinic for DOT for 6 months and had no EPTB or serious non-TB disease. | Recruited through a chest clinic. 930 were previously treated for <1.5 days and 310 for ≥ 1.5 days, all smear positive except two patients. Mean age was 33, 32 and 32 in reg 1, 2 and 3 respectively. Mean weight was 41.4, 40.5 and 40.9 kg respectively | 2[ER] 3[HZ]3/4[RH]2 | DOT | |

| 3[ER] 3[HZ]3/3[RH]2 | DOT | ||||||

| 2[EHRZ]3/4[RH]2 | DOT | ||||||

| [21] | Zaire | Open label controlled clinical trial among patients who attended outpatient clinics and were randomised to partly intermittent regimen | HIV sero-negative patients with first episode of PTB living in study area | Recruited in a study clinic, males constituted 50%. Mean age was 31±7.3. Resistance to H 19.1%, R 0%, E 2.3%, Z 1.2% and RH 0% | 2EHRZ/4[RH]2 | DOT and SA | |

| [22] | Hong Kong | Randomized controlled clinical trial of intermittent and daily six month regimens | Pulmonary smear positive Chinese TB adults aged 15 years or older with no more than two weeks TB chemotherapy | All patients had a positive baseline sputum smear and culture. 72% were males, 32% were more than 45 years, 35% < 25 years. Mean weight was 48kg. TB disease was gross in 1%, extensive in 9% and moderate in 17%, limited in 32% and slight in 41% of the patients | 2[EHRZ]3/4[EHRZ]3 | DOT | |

| 2[EHRZ]7/4[EHRZ]7 | DOT | ||||||

| [23] | Tanzania | Randomized controlled clinical trial of six month regimens, randomization was computer generated | Sputum positive pulmonary TB patients over aged of 18 years. Excluded were patients with renal, hepatic, cardiovascular, epilepsy and severe TB disease, pregnancy/lactation and history of adverse reactions to any study drugs | Mean age was 35.5±12.7, males/females 55/31, mean weight 49.6±7.9, patients with cavity 68% and HIV-32 patients. Recruited from hospital setting. | 2EHRZ/2RHZ-2RH | DOT | |

| [24] | Iran | Controlled clinical trial | Sputum positive pulmonary TB patients over aged of 15 years with cavity less than 5 cm and with no history of previous treatment or for less than 15 days. | All had cavities of less than 5cm. No other characteristics are provided. | 2EHRZ/4RHZ | Unspecified | |

| [25] | South Africa | Randomized comparative open label controlled clinical trial | Sputum positive pulmonary TB patients over aged of 15 years with no history of previous treatment or received treatment for less than 5 days. | Recruited from eight centers, 78.8% and 75.4% males were on RMP and RBT respectively, and corresponding mean age was 36.7±11 versus 34.2±11 while weight was 51.6±7.6 and 50.9±8.2. Extent of disease was minimal in 4 vs 3, advance in 58 vs 51, far advanced in 53 vs 49. | 2EHRZ/4[RHE]2 | Unspecified | Included extra pulmonary but not Tuberculous meningitis patients |

| 2EHRTZ/4[RTHE]2 | |||||||

| [26] | Thailand | Randomized controlled clinical trial | Sputum positive pulmonary TB patients | Recruited from TB clinic. No baseline details available | 2EHRZ/4TH | Unspecified | |

| [27] | Ireland | Randomized controlled clinical trial | Sputum positive new pulmonary TB patients | All were sputum positive new PTB patients recruited from a clinic. | 2EHRZ/4RH | Unspecified |

Table S4.

Data Abstraction table B: Treatment outcomes (48 data sets).

| Reference numbers | Sample size of treated pan susceptible pulmonary TB and all forms of resistance except MDR-TB (N) | N treated with each regimen | Treatment outcomes | Remarks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completed | Not completed | |||||||

| Success (cured and completed) | Failed | Died | Relapsed | Defaulted | ||||

| [1] | 105 | 57 | 25 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 18 | Total on FDC 57 |

| 48 | 25 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 16 | Total on separate formulation 48 | ||

| [2] | 67 | 67 | 58 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 67 patients on 2EHRZ/4RH |

| [3] | 1355 | 456 | 231 | 47 | 17 | 20 | 74 | The study included some HIV positives. |

| 466 | 248 | 32 | 9 | 30 | 89 | |||

| 433 | 249 | 36 | 12 | 9 | 74 | |||

| [4] | 146 | 39 | 39 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| [5] | 1585 | 798 | 591 | 19 | 8 | 48 | 9 | 39 on FDC and 38 patients on separate drugs were HIV positive. |

| 787 | 589 | 16 | 8 | 42 | 1 | |||

| [6] | 837 | 415 | 347 | 32 | 26 | 0 | 27 | |

| 422 | 320 | 27 | 21 | 0 | 55 | |||

| [7] | 198 | 198 | 193 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 67 of 198 patients were smear negative |

| [8] | 360 | 162 | 152 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 2 | Two patients on NTP regimen excluded due jaundice are reflected under TO |

| 198 | 188 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 1 | |||

| [9] | 520 | 175 | 171 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| 174 | 171 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | |||

| 171 | 161 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | |||

| [10] | 100 | 34 | 26 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| 34 | 26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | |||

| 32 | 24 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 6 | |||

| [11] | 122 | 61 | 44 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 5 | |

| 61 | 53 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |||

| [12] | 141 | 141 | 127 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | |

| [13] | 1159 | 582 | 468 | 24 | 11 | 7 | 43 | FDC |

| 577 | 477 | 16 | 4 | 4 | 41 | ST | ||

| [14] | 467 | 450 | 393 | 33 | 4 | 20 | 0 | |

| [15] | 825 | 305 | 279 | 11 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 112 patients excluded due to ineligibility |

| 263 | 234 | 1 | 0 | 28 | 0 | |||

| [16] | 170 | 165 | 144 | 5 | 1 | 10 | 2 | |

| [17] | 497 | 170 | 113 | 7 | 6 | 0 | 46 | |

| 165 | 103 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 53 | |||

| 162 | 105 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 53 | |||

| [18] | 434 | 236 | 208 | 12 | 3 | 10 | 4 | FDC-119 have no bacteriological follow up data |

| 198 | 179 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 4 | Loose drugs-108 have no bacteriological follow up data | ||

| [19] | 168 | 61 | 61 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Detailed outcomes not given for all patients by regimen |

| 58 | 58 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| [20] | 1240 | 407 | 338 | 37 | 0 | 32 | 0 | A third of included in the analysis were previously treated. |

| 415 | 363 | 26 | 0 | 26 | 0 | |||

| 418 | 334 | 48 | 0 | 36 | 0 | |||

| [21] | 188 | 188 | 171 | 5 | 0 | 10 | 2 | |

| [22] | 399 | 199 | 193 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 64 of drug sensitive and 13 of drug resistant had previous chemotherapy |

| 200 | 199 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| [23] | 98 | 87 | 86 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 32 patients were HIV positive |

| [24] | 88 | 88 | 87 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| [25] | 156 | 156 | 106 | 12 | 2 | 4 | 12 | Rifampicin group |

| 142 | 142 | 102 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 12 | Rifabutin group | |

| [26] | 102 | 102 | 97 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | |

| [27] | 67 | 67 | 67 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

Table S5.

Quality assessment scale for included studies.

| Reference numbers | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | [2] | [3] | [4] | [5] | [6] | [7] | [8] | [9] | [10] | [11] | [12] | [13] | [14] | [15] | [16] | [17] | [18] | [19] | [20] | [21] | [22] | [23] | [24] | [25] | [26] | [27] | ||

| Item | Questions Scale: Yes =1, No = 0, Unable to ascertain = 0 | Score for each item | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1. | as the study's target population a close representation of the target TB population in relation to age, immune status, susceptibility and diagnoses? | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2. | Was the sample recruited from a source that closely mirrored the target population? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3. | Was some sort of random selection used to select the sample or was a census undertaken? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 4. | Was a non-response <20%? | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 5. | Was data collected objectively regarding outcomes or was it self- reported or through a proxy?(objectively =1, self- reported/proxy =0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6. | Were the definition of case outcomes clearly specified in the study and appropriate and acceptable or ineligible patients could not be excluded? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a) Success | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| b) Failed | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| c) Relapsed | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| d) Defaulted | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 7. | Was data collected in the same way for all subjects in the study | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8. | Was the definition of a New case of TB acceptable? | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 9. | Was there more than 20% exclusions at analysis (i.e. patients who could not be classified e.g. transfer out and unknown outcome)? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 10. | Was the length of follow up appropriate to optimally determine the outcomes of interest (at least one year)? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Total score | 13 scores max | 5 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 11 | 10 | 7 | 11 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 8 | 11 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

Supplementary References

- 1.Su WJ, Perng RP. Fixed-dose combination chemotherapy (Rifater/Rifinah) for active pulmonary tuberculosis in Taiwan: a two-year follow-up. In J Tuberc Lung Dis 2002;6:1029–1032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharifi-Mood B, Metanat M, Alavi-Naini R, Kouhpayeh HR, Salehi M, Naderi M, Hashemi-Shahri SM, Naser-Poor T. The comparison of six-month and four-month regimens of chemotherapy in the treatment of smear positive pulmonary tuberculosis. Journal of Medical Sciences 2006;6:108–111. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nunn AJ, Jindani A, Enarson DA. Results at 30 months of a randomised trial of two 8-month regimens for the treatment of tuberculosis. In J Tuberc Lung Dis 2011;15:741–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macnab MF, Bohmer PD, Seager JR. Evaluation of the 3-drug combination, Rifater, versus 4-drug therapy in the ambulatory treatment of tuberculosis in Cape Town. S Afr Med J 1994;84:325–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lienhardt C, Cook SV, Burgos M, Yorke-Edwards V, Rigouts L, Anyo G, Kim SJ, Jindani A, Enarson DA, Nunn AJ; Study C Trial Group. Efficacy and safety of a 4-drug fixed-dose combination regimen compared with separate drugs for treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis: the Study C randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2011;305:1415–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamol Ratanakul P, Sawert H, Lertmaharit S. Effectiveness of ‘directly observed therapy, short course’ (DOTS) in the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis in Thailand [abstract]. J Clin-Epidemiol 1999; 52(Suppl 1):16s. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson JL, Hadad DJ, Dietze R, Maciel EL, Sewali B, Gitta P, Okwera A, Mugerwa RD, Alcaneses MR, Quelapio MI, Tupasi TE, Horter L, Debanne SM, Eisenach KD, Boom WH. Shortening treatment in adults with noncavitary tuberculosis and 2-month culture conversion. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;180:558–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gravendeel JM, Asapa AS, Becx-Bleumink M, Vrakking HA. Preliminary results of an operational field study to compare side-effects, complaints and treatment results of a single-drug short-course regimen with a four-drug fixed-dose combination (4FDC) regimen in South Sulawesi, Republic of Indonesia. Tuberculosis (Edinburgh, Scotland) Vol. 83, 2003:183–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzalez-Montaner LJ, Natal S, Yongchaiyud P, Olliaro P. Rifabutin for the treatment of newly-diagnosed pulmonary tuberculosis: A multinational, randomized, comparative study versus Rifampicin. Rifabutin Study Group. Tuber Lung Dis 1994;75:341–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faisal AR, Qazi RA, Iqbal M, Waseemuddin J, Rehmani F, Bashir T. Effectiveness of directly observed treatment strategy (dots) as compared to self-administered therapy in tuberculosis. Ann Pak Inst Med Sci 2005;1:79–83. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chuchottaworn C, Saipan B, Kittisup C, Cheewakul K. Adverse drug reactions and outcome of short course anti-tuberculosis drugs between single daily dose and split drug dose (BID) in pulmonary tuberculosis. J Med Assoc Thai 2012;95:S1–S5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.A controlled trial of 6 months’ chemotherapy in pulmonary tuberculosis. Final report: results during the 36 months after the end of chemotherapy and beyond. British Thoracic Society. Br J Dis Chest 1984;78:330–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartacek A, Schutt D, Panosch B, Borek M; Rimstar 4-FDC Study Group. Comparison of a four-drug fixed-dose combination regimen with a single tablet regimen in smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2009;13:760–766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evaluation of a non-rifampicin continuation phase (6HE) following thrice-weekly intensive phase for the treatment of new sputum positive pulmonary tuberculosis. Indian J Tuberc 2007;54:84–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.A controlled clinical trial of oral short-course regimens in the treatment of sputum-positive pulmonary tuberculosis. Tuberculosis Research Centre. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 1997;1:509–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jawahar MS, Banurekha VV, Paramasivan CN, Rahman F, Ramachandran R, Venkatesan P, Balasubramanian R, Selvakumar N, Ponnuraja C, Iliayas AS, Gangadevi NP, Raman B, Baskaran D, Kumar SR, Kumar MM, Mohan V, Ganapathy S, Kumar V, Shanmugam G, Charles N, Sakthivel MR, Jagannath K, Chandrasekar C, Parthasarathy RT, Narayanan PR. Randomized clinical trial of thrice-weekly 4-month moxifloxacin or gatifloxacin containing regimens in the treatment of new sputum positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients. PloS One 2013;8:e67030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walley JD, Khan MA, Newell JN, Khan MH. Effectiveness of the direct observation component of DOTS for tuberculosis: a randomised controlled trial in Pakistan. Lancet 2001;357:664–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suryanto AA, van den Broek J, Hatta M, de Soldenhoff R, van der Werf MJ. Is there an increased risk of TB relapse in patients treated with fixed-dose combination drugs in Indonesia? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2008;12:174–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Felten MK. Importance of rifampicin in combined daily/intermittent chemotherapy for tuberculosis. S Afr Med J 1989;75:524–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santha T, Rehman F, Mitchison DA, Sarma GR, Reetha AM, Prabhaker R; ulosis Research Centre, Indian Council of Medical Research. Split-drug regimens for the treatment of patients with sputum smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis--a unique approach. Trom Med Int Health 2004;9:551–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perriens JH, St Louis ME, Mukadi YB, Brown C, Prignot J, Pouthier F, Portaels F, Willame JC, Mandala JK, Kaboto M, et al. Pulmonary tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients in Zaire. A controlled trial of treatment for either 6 or 12 months. N Eng J Med 1995;332:779–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Controlled trial of four thrice-weekly regimens and a daily regimen all given for 6 months for pulmonary tuberculosis. Lancet 1981;1:171–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kennedy N, Berger L, Curram J, Fox R, Gutmann J, Kisyombe GM, Ngowi FI, Ramsay AR, Saruni AO, Sam N, Tillotson G, Uiso LO, Yates M, Gillespie SH. Randomized controlled trial of a drug regimen that includes ciprofloxacin for the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis 1996;22:827–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baba H, Shinkai A, Izuchi R, Azuma Y. [Long-term results of short-course chemotherapy of pulmonary tuberculosis (second study--A). Results up to 6 years after the end of treatment with 4–6 month chemotherapy of pulmonary tuberculosis.] Kekkaku 1987;62:329–339 [Article in Japanese.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGregor MM, Olliaro P, Wolmarans L, Mabuza B, Bredell M, Felten MK, Fourie PB. Efficacy and safety of rifabutin in the treatment of patients with newly diagnosed pulmonary tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;154:1462–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Punnotok J, Pumprueg U, Chakorn T. A comparison of two short course tuberculosis chemotherapy regimens, both using Rifater during an intensive phase, with a 3 year follow-up. J Med Assoc Thai 1995;78:298–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howell F, O’Laoide R, Kelly P, Power J, Clancy L. Short course chemotherapy for pulmonary tuberculosis. A randomised controlled trial of a six month versus a nine month oral regimen. Ir Med J 1989;82:11–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Footnotes

Details of the Search String

PubMed search

“Tuberculosis”[Mesh] OR Tuberculosis OR Tuberculoses OR

“Kochs Disease” OR “Koch’s Disease” OR “Koch Disease”

AND

“Therapeutics”[Mesh] OR Therapeutics OR Therapeutic OR

Treatment OR Treatments OR Therapy OR Therapies

AND

“Treatment Outcome”[Mesh] OR Effectiveness OR Efficacy OR

Failure OR Relapse OR “Drug resistance”

Cochrane search

#1: MeSH descriptor: [Tuberculosis] explode all trees

#2: Tuberculosis or Tuberculoses or “Kochs Disease” or “Koch’s Disease” or “Koch Disease”

#3: MeSH descriptor: [Therapeutics] explode all trees

#4: Therapeutics or Therapeutic or Treatment or Treatments or Therapy or Therapies

#5: MeSH descriptor: [Treatment Outcome] explode all trees

#6:Effectiveness or Efficacy or Failure or Relapse or “Drug resistance”

#7: #1 or #2

#8: #3 or #4

#9: #5 or #6

#10: #7 and #8 and #9

Embase search

‘tuberculosis’/exp OR tuberculosis OR tuberculoses OR ‘kochs disease’ OR ‘koch disease’

AND

(‘therapeutics’/exp OR therapeutics OR therapeutic OR treatment OR treatments OR ‘therapy’/exp OR therapy OR therapies)

AND

(‘treatment outcome’/exp OR effectiveness OR efficacy OR failure OR ‘relapse’/exp OR relapse OR ‘drug resistance’/exp OR ‘drug resistance’)

AND

([controlled clinical trial]/lim OR [randomized controlled trial]/lim)

AND

[english]/lim

AND

[embase]/lim

References

- 1.Gebremariam MK, Bjune GA, Frich JC. Barriers and facilitators of adherence to TB treatment in patients on concomitant TB and HIV treatment: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2010;10:651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mandal PK, Mandal A, Bhattacharyya SK. Comparing the Daily Versus the Intermittent Regimens of the Anti-Tubercular Chemotherapy in the Initial Intensive Phase in Non-HIV, Sputum Positive, Pulmonary Tuberculosis Patients. J Clin Diagn Res 2013;7:292–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Menzies D, Benedetti A, Paydar A, Martin I, Royce S, Pai M, Vernon A, Lienhardt C, Burman W. Effect of duration and intermittency of rifampin on tuberculosis treatment outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. Treatment of tuberculosis: guidelines: World Health Organization, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. WHO, Global Tuberculosis Report. Printed in France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mwandumba HC, Squire SB. Fully intermittent dosing with drugs for treating tuberculosis in adults. The Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001;(4):Cd000970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barendregt JJ, Doi SA, Lee YY, Norman RE, Vos T. Meta-analysis of prevalence. J Epidemiol Community Health 2013;67:974–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, Blyth F, March L, Bain C, Baker P, Smith E, Buchbinder R. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:934–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doi SA, Barendregt JJ, Williams GM, Khan S, Thalib L. Simulation Comparison of the Quality Effects and Random Effects Methods of Meta-analysis. Epidemiology 2015;26:e42–e44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO. WHO, Table A2.1. Definitions of tuberculosis cases and treatment outcomes. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO. Definitions and reporting framework for tuberculosis–2013 revision. World Health Organization Document 2013: 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO. WHO, Guidelines for the programmatic management of drug-resistant tuberculosis, Emergency update 2008. 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland: WHO Press, World Health Organization, 2008:1–272. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doi SA, Thalib L. A quality-effects model for meta-analysis. Epidemiology 2008;19:94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noma H. Confidence intervals for a random-effects meta-analysis based on Bartlett-type corrections. Stat Med 2011;30:3304–3312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doi SA, Williams GM. Methods of clinical epidemiology. New York: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Field AP, Gillett R. How to do a meta-analysis. Br J Math Stat Psychol 2010;63:665–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sterne JA1, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JP, Terrin N, Jones DR, Lau J, Carpenter J, Rücker G, Harbord RM, Schmid CH, Tetzlaff J, Deeks JJ, Peters J, Macaskill P, Schwarzer G, Duval S, Altman DG, Moher D, Higgins JP. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011;343:d4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartacek A, Schutt D, Panosch B, Borek M; Rimstar 4-FDC Study Group. Comparison of a four-drug fixed-dose combination regimen with a single tablet regimen in smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2009;13:760–766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nunn AJ, Jindani A, Enarson DA. Results at 30 months of a randomised trial of two 8-month regimens for the treatment of tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2011;15:741–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lienhardt C, Cook SV, Burgos M, Yorke-Edwards V, Rigouts L, Anyo G, Kim SJ, Jindani A, Enarson DA, Nunn AJ; Study C Trial Group. Efficacy and safety of a 4-drug fixed-dose combination regimen compared with separate drugs for treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis: the Study C randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2011;305:1415–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kennedy N, Berger L, Curram J, Fox R, Gutmann J, Kisyombe GM, Ngowi FI, Ramsay AR, Saruni AO, Sam N, Tillotson G, Uiso LO, Yates M, Gillespie SH. Randomized controlled trial of a drug regimen that includes ciprofloxacin for the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis 1996;22:827–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson JL, Hadad DJ, Dietze R, Maciel EL, Sewali B, Gitta P, Okwera A, Mugerwa RD, Alcaneses MR, Quelapio MI, Tupasi TE, Horter L, Debanne SM, Eisenach KD, Boom WH. Shortening treatment in adults with noncavitary tuberculosis and 2-month culture conversion. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:558–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Santha T, Rehman F, Mitchison DA, Sarma GR, Reetha AM, Prabhaker R; ulosis Research Centre, Indian Council of Medical Research. Split-drug regimens for the treatment of patients with sputum smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis--a unique approach. Trom Med Int Health 2004;9:551–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGregor MM, Olliaro P, Wolmarans L, Mabuza B, Bredell M, Felten MK, Fourie PB. Efficacy and safety of rifabutin in the treatment of patients with newly diagnosed pulmonary tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;154:1462–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gonzalez-Montaner LJ, Natal S, Yongchaiyud P, Olliaro P. Rifabutin for the treatment of newly-diagnosed pulmonary tuberculosis: A multinational, randomized, comparative study versus Rifampicin. Rifabutin Study Group. Tuber Lung Dis 1994;75:341–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Controlled trial of four thrice-weekly regimens and a daily regimen all given for 6 months for pulmonary tuberculosis. Lancet 1981;1:171–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharifi-Mood B, Metanat M, Alavi-Naini R, Kouhpayeh HR, Salehi M, Naderi M, Hashemi-Shahri SM, Naser-Poor T. The comparison of six-month and four-month regimens of chemotherapy in the treatment of smear positive pulmonary tuberculosis. J Med Sci 2006;6:108–111. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Macnab MF, Bohmer PD, Seager JR. Evaluation of the 3-drug combination, Rifater, versus 4-drug therapy in the ambulatory treatment of tuberculosis in Cape Town. S Afr Med J 1994;84:325–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chuchottaworn C, Saipan B, Kittisup C, Cheewakul K. Adverse drug reactions and outcome of short course anti-tuberculosis drugs between single daily dose and split drug dose (BID) in pulmonary tuberculosis. J Med Assoc Thai 2012;95:S1–S5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jawahar MS, Banurekha VV, Paramasivan CN, Rahman F, Ramachandran R, Venkatesan P, Balasubramanian R, Selvakumar N, Ponnuraja C, Iliayas AS, Gangadevi NP, Raman B, Baskaran D, Kumar SR, Kumar MM, Mohan V, Ganapathy S, Kumar V, Shanmugam G, Charles N, Sakthivel MR, Jagannath K, Chandrasekar C, Parthasarathy RT, Narayanan PR. Randomized clinical trial of thrice-weekly 4-month moxifloxacin or gatifloxacin containing regimens in the treatment of new sputum positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients. PloS One 2013;8:e67030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gravendeel JM, Asapa AS, Becx-Bleumink M, Vrakking HA. Preliminary results of an operational field study to compare side-effects, complaints and treatment results of a single-drug short-course regimen with a four-drug fixed-dose combination (4FDC) regimen in South Sulawesi, Republic of Indonesia. Tuberculosis (Edin) 2003;83:183–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Felten MK. Importance of rifampicin in combined daily/intermittent chemotherapy for tuberculosis. S Afr Med J 1989;75:524–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suryanto AA, van den Broek J, Hatta M, de Soldenhoff R, van der Werf MJ. Is there an increased risk of TB relapse in patients treated with fixed-dose combination drugs in Indonesia? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2008;12:174–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perriens JH, St Louis ME, Mukadi YB, Brown C, Prignot J, Pouthier F, Portaels F, Willame JC, Mandala JK, Kaboto M, et al. Pulmonary tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients in Zaire. A controlled trial of treatment for either 6 or 12 months. N Eng J Med 1995;332:779–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walley JD, Khan MA, Newell JN, Khan MH. Effectiveness of the direct observation component of DOTS for tuberculosis: a randomised controlled trial in Pakistan. Lancet 2001;357:664–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kamolratanakul P, Sawert H, Lertmaharit S, Kasetjaroen Y, Akksilp S, Tulaporn C, Punnachest K, Na-Songkhla S, Payanandana V. Randomized controlled trial of directly observed treatment (DOT) for patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in Thailand. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1999;93:552–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Evaluation of a non-rifampicin continuation phase (6HE) following thrice-weekly intensive phase for the treatment of new sputum positive pulmonary tuberculosis. Indian J Tuberc 2007;54:84–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Faisal AR, Qazi RA, Iqbal M, Waseemuddin J, Rehmani F, Bashir T. Effectiveness of directly observed treatment strategy (dots) as compared to self-administered therapy in tuberculosis. Ann Pak Inst Med Sci 2005;1:79–83. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Su WJ, Perng RP. Fixed-dose combination chemotherapy (Rifater/Rifinah) for active pulmonary tuberculosis in Taiwan: a two-year follow-up. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2002;6:1029–1032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.A controlled trial of 6 months’ chemotherapy in pulmonary tuberculosis. Final report: results during the 36 months after the end of chemotherapy and beyond. British Thoracic Society. Br J Dis Chest 1984;78:330–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baba H, Shinkai A, Izuchi R, Azuma Y. [Long-term results of short-course chemotherapy of pulmonary tuberculosis (second study--A). Results up to 6 years after the end of treatment with 4–6 month chemotherapy of pulmonary tuberculosis.] Kekkaku 1987;62:329–339 [Article in Japanese.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Punnotok J, Pumprueg U, Chakorn T. A comparison of two short course tuberculosis chemotherapy regimens, both using Rifater during an intensive phase, with a 3 year follow-up. J Med Assoc Thai 1995;78:298–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Howell F, O’Laoide R, Kelly P, Power J, Clancy L. Short course chemotherapy for pulmonary tuberculosis. A randomised controlled trial of a six month versus a nine month oral regimen. Ir Med J 1989;82:11–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.A controlled clinical trial of oral short-course regimens in the treatment of sputum-positive pulmonary tuberculosis. Tuberculosis Research Centre. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 1997;1:509–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Felten MK. Importance of rifampicin in combined daily/intermittent chemotherapy for tuberculosis. S Afr Med J 1989;75:524–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hunter JP, Saratzis A, Sutton AJ, Boucher RH, Sayers RD, Bown MJ. In meta-analyses of proportion studies, funnel plots were found to be an inaccurate method of assessing publication bias. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:897–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Banu Rekha VV, Rajaram K, Kripasankar AS, Parthasarathy R, Umapathy KC, Sheikh I, Selvakumar N, Victor M, Niruparani C, Sridhar R, Jawahar MS. Efficacy of the 6-month thrice-weekly regimen in the treatment of new sputum smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis under clinical trial conditions. Natl Med J India 2012;25:196–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chaisson RE, Clermont HC, Holt EA, Cantave M, Johnson MP, Atkinson J, Davis H, Boulos R, Quinn TC, Halsey NA. Six-month supervised intermittent tuberculosis therapy in Haitian patients with and without HIV infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;154:1034–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mandal PK, Mandal A, Bhattacharyya SK. Comparing the Daily Versus the Intermittent Regimens of the Anti-Tubercular Chemotherapy in the Initial Intensive Phase in Non-HIV, Sputum Positive, Pulmonary Tuberculosis Patients. J Clin Diagn Res 2013;7:292–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chang KC, Leung CC, Yew WW, Chan SL, Tam CM. Dosing schedules of 6-month regimens and relapse for pulmonary tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:1153–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pyle MM. Ethambutol in the retreatment and primary treatment of tuberculosis: a four-year clinical investigation. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1966;135:835–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li J, Munsiff SS, Driver CR, Sackoff J. Relapse and acquired rifampin resistance in hiv-infected patients with tuberculosis treated with rifampin- or rifabutin-based regimens in New York City, 1997–2000. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41:83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Munro SA, Lewin SA, Smith HJ, Engel ME, Fretheim A, Volmink J. Patient adherence to tuberculosis treatment: a systematic review of qualitative research. PLoS Med 2007;4:e238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chirwa T, Nyasulu P, Chirwa E, Ketlogetswe A, Bello G, Dambe I, Ndalama D, Joshua M. Levels of tuberculosis treatment adherence among sputum smear positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients attending care at Zomba Central hospital, southern Malawi, 2007–2008. PloS One 2013;8:e63050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1.

TB treatment outcomes – IVhet model (fixed effects with over dispersion correction).

| Regimen | Success | Failed | Relapsed | Defaulted | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rifampicin throughout | |||||

| Intermittent (n=9) | 0.87 (0.80–0.91) | 0.06 (0.02–0.10) | 0.07 (0.03–0.11) | 0.00 (0.00–0.02) | 1 |

| Daily (n=19) | 0.89 (0.82–0.95) | 0.04 (0.00–0.08) | 0.01 (0.00–0.03) | 0.05 (0.01–0.10) | 1 |

| Overall | 0.90 (0.82–0.95) | 0.04 (0.00–0.08) | 0.01 (0.00–0.03) | 0.05 (0.01–0.10) | 1 |