Abstract

Astrocytes are the most abundant cells in the central nervous system. They play critical roles in neuronal homeostasis through their physical properties and neuron-glia signaling pathways. Astrocytes become reactive in response to neuronal injury and this process, referred to as reactive astrogliosis, is a common feature accompanying neurodegenerative conditions, particularly Alzheimer’s disease. Reactive astrogliosis represents a continuum of pathobiological processes and is associated with morphological, functional and gene expression changes of varying degrees. There has been a substantial growth of knowledge regarding the signaling pathways regulating glial biology and pathophysiology in recent years. Here we attempt to provide an unbiased review of some of the well-known players, namely calcium, proteoglycan, TGFβ, NFκB, and complement, in mediating neuron-glia interaction under physiological conditions as well as in Alzheimer’s disease.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, astrocytes, calcium, complement, microglia, neuron-glia interaction, NFκB, proteoglycan, TGF-β

Introduction

From invertebrate animals to mammals, the central nervous system (CNS) exhibits tremendous cell type diversity. Among these, cells capable of conducting rapid electrical signals are designated as neurons, while all other cell types are collectively categorized as glia. The classical view of neuroscience considers neurons to be the central players with glia playing a passive and supportive role. However, there has been a growing interest in glia, and recent work has challenged this neurocentric view. It is now increasingly appreciated that glia play dynamic structural and signaling roles, both during development and in adult and aging brains, and impairment of these properties dictate many of the neurological conditions.

There are three major glial cell types in the CNS: microglia, astrocytes (also known as astroglia), and oligodendrocytes; the latter are highly specified cells that function to insulate axons via the formation of myelin sheath around axons. Microglia are considered the resident macrophages in the brain where they play prominent roles in immune surveillance, phagocytosis and neuroinflammatory processes. Astroglia are the most abundant cell type in the CNS which exert diverse physiological functions through their close association and communication with neurons and other brain structures. Like microglia, astrocytes possess immune and inflammatory properties when activated. This process, referred to as reactive astrogliosis, is associated with morphology, gene expression and functional changes, and is a common feature accompanying many neuronal injury and neurodegenerative conditions, particularly Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia in the aged population. The pathological hallmarks of AD include extracellular amyloid plaque deposition, intraneuronal neurofibrillary tangle accumulation, synaptic dysfunction and neurodegeneration (Stancu et al. 2014). In addition, the diseased brains are associated with profound neuroinflammation characterized by reactive astrogliosis, microgliosis and increased release of inflammatory cytokines (Heneka et al. 2015, Hensley 2010, Orsini et al. 2014, Lemere 2013). Mutations in APP and presenilins (PSEN) cause a subset of early onset familial AD, establishing their central roles in disease pathogenesis (Guo et al. 2012, Wang et al. 2014b). The identification of multiple genetic risk factors with immune and inflammatory properties, such as TREM2, CR1, CLU (ApoJ), CD33, ABCA7, etc., strongly implicates innate immunity plays a contributing role in AD (Heneka et al. 2015, Guerreiro et al. 2013). Both positive and negative effects of neuroinflammation have been proposed, and these differing outcomes are likely attributed by differences in the timing, duration, and/or strength of the responses, triggered by a wide range of upstream stimulators and the many downstream effectors, either unique to the specific cells in the CNS or through the crosstalk among these cell types (Lucin & Wyss-Coray 2009, Garden & La Spada 2012).

The role of microglia in neuronal health and disease has been extensively studied and discussed (Wyss-Coray & Rogers 2012, Landel et al. 2014, Ransohoff & Brown 2012, Ulrich et al. 2014). The primary objective of this review is to provide an overview of the signaling pathways pertinent to astrocytes and reactive astrocytes, specifically calcium, proteoglycans, TGF-β, NFκB and complement, and describe their impact on neuronal function in physiological conditions as well as in Alzheimer’s disease. Understandably, it is not possible to cover all the potential pathways in a single review. Other signaling molecules that exhibit widespread functions across cell types, such as lipids (Walter & van Echten-Deckert 2013, Wang et al. 2015), oxidative species (Moncada & Bolanos 2006, Landel et al. 2014, Kukreja et al. 2014) and metabolic intermediates (Hertz 2004, Lovatt et al. 2007, Hoos et al. 2014, Kang et al. 2014), will not be discussed in detail but only mentioned as necessary. While we attempt to focus this review on astrocytes, microglia and neurons express many of the common factors and regulatory pathways that act as integral components of the neuron-glia signaling network. Indeed it would be difficult to pinpoint an astrocyte “only” effect, particularly under pathological conditions. Accordingly, we will often discuss the effects of these pathways in this border context.

Astrocytes and reactive astrocytes

Astroglia are the most abundant cell type in the CNS that exert diverse physiological functions through their close association and communication with neuron and with other brain structures. Astrocytes extend many fine branching processes, putting them in direct contact with neuronal cell bodies, dendrites and synaptic terminals. This physical proximity allows astrocytes to sense and respond to neuronal activities. Astroglia express and secrete many signaling molecules that mediate synapse formation and synaptic transmission (Barres 2008, Allen & Barres 2009). Astrocytes also express neurotransmitter receptors, through which they potently regulate neurotransmitter recycling at synaptic sites through the formation of “tripartite” synapses consisting of astroglial projections and neuronal pre- and postsynaptic terminals (Halassa et al. 2007, Perea et al. 2009). Astrocytic end-feet are an essential constituent of the blood brain barrier. Through these widespread contact properties, astroglia have the ability to adjust blood flow for oxygen, ATP and glucose supplies, in addition to maintaining ionic concentrations in the extracellular matrix, to name but a few (Reviewed in: Garden & La Spada 2012, Sofroniew & Vinters 2010). Through the expression of aquaporin 4 water channels in the astrocytic vascular end-feet, astroglia play a vital role in the newly discovered glymphatic system, which is a brain drainage system implicated in the clearance of both Aβ and tau (Iliff et al. 2013, Iliff et al. 2012, Xie et al. 2013, Nedergaard 2013).

Astrocytes become reactive in response to various triggers, and this process is associated with morphological, molecular and functional changes. Reactive astrogliosis, marked by GFAP (glial fibrillary acidic protein) immunoreactivity, is a common feature associated with both acute brain injury and chronic neurological conditions. While it is generally believed that reactive gliosis contributes to disease pathogenesis, it is often overlooked that this process covers a continuum of changes with varying degrees, ranging from subtle and reversible alterations of physiological processes in mild forms to long-lasting scar formation in the most severe cases (Sofroniew & Vinters 2010, Anderson et al. 2014, Verkhratsky et al. 2014). Thus, the signaling pathways described below and their effects on neuronal function and dysfunction are expected to vary depending on the state of the astrocytes and the degree of reactive gliosis, although this can be difficult to define precisely.

Calcium

Astroglial calcium plays pivotal roles in intracellular signaling and intercellular communication. The cytosolic free calcium concentration is critically controlled by extracellular influx and intracellular storage release. Intracellular calcium transients and intercellular calcium waves are the basic forms of astrocytes which, through intimate connections, communicate among themselves and with neurons (Scemes & Giaume 2006). In particular, the production of inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) leads to the activation of IP3 receptors (IP3R) and calcium release from internal storages, especially the endoplasmic reticulum, and the rise of calcium transients promotes astroglial release of stimulating substances such as purines (ATP and adenosine), GABA, D-serine, and glutamate, collectively termed as gliotransmitters. The calcium-mediated release of glutamate from astrocytes promotes neurotransmission at the tripartite synaptic sites. The spread of ATP and glutamate can regenerate calcium mobilization in adjacent cells through the activation of purinergic receptors or metabotropic glutamate receptors, which in turn induce IP3 production inside the cells. As such, calcium transients inside one cell can initiate calcium changes in surrounding cells through the conversion of intracellular calcium transients to intercellular calcium waves, allowing astrocytes to execute both synchronous as well as differential responses through limited messenger diffusion (Reviewed in: Araque et al. 2014, Rusakov 2015).

Substantial evidence supports a significant role of calcium dysregulation in AD pathogenesis (LaFerla 2002, Peterson et al. 1985, Garwood et al. 2013, Bezprozvanny & Hiesinger 2013). Both APP and presenilins were found to regulate calcium homeostasis and calcium-dependent synaptic function (Yang et al. 2007, Yang et al. 2009, Hamid et al. 2007, Leissring et al. 2002, Stutzmann et al. 2006, Tu et al. 2006, Johnston et al. 2006, Lee et al. 2002). Neurotoxicity induced by protein aggregates, such as Aβ, may be conferred by their direct disturbance of calcium signaling in neurons (Kuchibhotla et al. 2008, Choo et al. 2004, Tang et al. 2003, Del Prete et al. 2014, Lopez et al. 2008, Mattson 2007, Zundorf & Reiser 2011, Demuro & Parker 2013, Armato et al. 2012, Ye et al. 1997, Chiarini et al. 2009) or indirectly through affecting calcium homeostasis in glial cells (Alberdi et al. 2013, Chow et al. 2010, Orellana et al. 2011). In mouse models of AD, calcium channels including ATP-gated purinergic receptor cation channels and voltage-gated calcium channels were overexpressed in plaque-surrounding reactive astrocytes and microglia (Willis et al. 2010, Parvathenani et al. 2003). These astrocytes were shown to exhibit escalated basal calcium transients and intercellular calcium waves (Delekate et al. 2014, Kuchibhotla et al. 2009, Riera et al. 2011, Lim et al. 2014), which may trigger the release of toxic factors or dysregulation of neuronal calcium-regulated receptors (Abramov et al. 2003, Hashioka et al. 2012, Kaushal et al. 2007, Orellana et al. 2011). In particular, dysregulation of astroglial calcium has been implicated in extrasynaptic glutamate receptor activation and associated glutamate excitotoxicity (Rudy et al. 2015, Paula-Lima et al. 2013). It may also produce reactive oxidative species leading to neuronal oxidative stress (Ye et al. 2015, Pirttimaki et al. 2013, Abramov et al. 2004, Zhu et al. 2006)(Zhao & Zhao 2013, Axelsen et al. 2011, Pohanka 2014). Consistent with these assessments, calcium channel blockers have been reported to inhibit the neurotoxicity of activated glia (Hashioka et al. 2012, Maezawa et al. 2011). Interestingly, astrocytes are the major cells for antioxidant glutathione (GSH) synthesis where it exhibits distinct responses to different Aβ species (Ye et al. 2015). Whereas monomeric Aβ increases GSH release, aggregated Aβ leads to reduced GSH, consistent with the in vivo observation that GSH levels are higher in pre-plaque AD animals, but are reduced when plaque pathology manifests (Ye et al. 2015).

Overall, overwhelming evidence supports a prominent role of astrocytic calcium in neuronal homeostasis and AD pathogenesis, which are mediated through diverse mechanisms. Although an Aβ triggered astrocytic calcium response has been well documented (Vincent et al. 2010, Mattson & Chan 2003, Bezprozvanny 2009), the astroglial receptors mediating this response has been elusive. Some speculated that the calcium-permeable α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (α7nAChRs) expressed in astrocytes may be the receptor (Pirttimaki et al. 2013, Lee et al. 2014), others implicated the metabotropic glutamate type-5 receptor (mGluR5) as a candidate, which may become clustered on astrocytic membrane due to Aβ –induced biophysical changes (Shrivastava et al. 2013, Hicks et al. 2008, Yang et al. 2010). Further investigation of these receptors will provide better insights into the calcium-dependent neuron-astroglia crosstalk in AD.

Proteoglycans

Proteoglycans are glycosylated proteins composed of a protein core and glycosaminoglycan (GAG) chains (Iozzo & Schaefer 2015). The proteoglycans are mainly detected on cell surfaces and in the extracellular matrix (ECM). The cell surface proteoglycans can bi-directionally regulate signaling through interaction with both ligand and membrane receptor proteins (Clark 2008). Some cell surface proteoglycans themselves are receptors capable of conducting intracellular signaling upon activation (Christianson & Belting 2014). Secreted proteoglycans are major components of the ECM where they maintain ECM homeostasis through binding among themselves and with other molecules, such as collagen (Yanagishita 1993, Kim et al. 2011).

Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs) and heparin sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) are the two main types of proteoglycans in the brain, which are produced in both neurons and glia (Bandtlow & Zimmermann 2000). The functions of neuronal cell surface proteoglycans have been covered in previous reviews (Cui et al. 2013, Schaefer & Schaefer 2010, Maeda 2015). Here we discuss how glial secreted proteoglycans regulate neuronal processes and their possible involvement in AD pathogenesis.

Astrocyte-derived proteoglycans are essential components of the brain ECM that facilitate neurite outgrowth, axon guidance and synaptogenesis, among others (Farhy Tselnicker et al. 2014). Certain HSPGs, such as syndecan 4, glypican 6 and perlecan, are specifically expressed in astrocytes (Giamanco & Matthews 2012, Faissner et al. 2010, Yamada et al. 1997, Allen et al. 2012). Secreted glypican 4 and 6 from astrocytes are required for synaptogenesis and AMPAR recruitment, although whether the glypicans function through specific neuronal receptors or through modulation of other growth receptors remains to be determined (Allen et al. 2012). Elimination of CSPG brevican and neurocan induced astrocyte-dependent, dual-phased effects on synaptic puncta numbers displaying initial promoting, but later suppressing, activities (Pyka et al. 2011, Geissler et al. 2013), which implicates their possible contrasting roles in synaptogenesis and synapse maintenance. Results from axon regeneration studies suggest that CSPGs produced from reactive astrocytes are the main source of glial scars formed after injury and are inhibitory for axonal growth and myelination (Pendleton et al. 2013, Deng et al. 2015, Bradbury et al. 2002, Cafferty et al. 2007, Pizzorusso et al. 2002, Sharma et al. 2012). It was suspected that this may be mediated via specific CSPG receptors or through non-specific repulsion between CSPGs and axons due to charge differences (Sharma et al. 2012). However, a recent study on neural-glial 2 (NG2) proteoglycan revealed that proteoglycans have high affinity for axons and thus, instead of repulsion, the inhibitory effects may be caused by the trapping of axons in the scar area (Filous et al. 2014).

Proteoglycans may contribute to AD pathophysiology through multiple pathways. In neurons it is known that APP is processed during sorting and trafficking (Wang et al. 2014b, Del Prete et al. 2014). APP splicing variants lacking exon 15 are modified by GAG chains and are rapidly transported to the cell surface through indirect endosomal sorting (Mihov et al. 2015). This GAG-directed redistribution of APP could result in differential APP processing and Aβ generation (Cui et al. 2012, von Einem et al. 2015, Zheng & Koo 2011, Vassar et al. 1999). Proteoglycans have been shown to interact with APP (Narindrasorasak et al. 1991, Buée et al. 1993), and disruption of the interaction may inhibit its physiological function, such as soluble APP (sAPP)-induced neurite outgrowth (Small et al. 1994, Clarris et al. 1994). Proteoglycans are known to associate with both amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, and their expressions are dysregulated in AD (Snow et al. 1988, DeWitt et al. 1993, Perry et al. 1991, Leveugle & Fillit 1994, Bellucci 2007). These may be caused by a direct induction of astrocytic proteoglycan overexpression by Aβ (Canning et al. 1993), or as a consequence of astroglial reactivation (Karimi-Abdolrezaee & Billakanti 2012, Properzi et al. 2003, Dow & Wang 1998). Aberrantly expressed proteoglycans may promote Aβ aggregation by facilitating its structural conversion from non-amyloidogenic random coil to amyloidogenic β-sheet through hydrophobic and ionic interactions between Aβ and proteoglycans (Snow et al. 1994b, Geneste et al. 2014). It may also attenuate Aβ clearance by inhibiting Aβ proteolysis due to the steric shielding of Aβ peptide by naturally protease-resistant GAG chains (Gupta-Bansal et al. 1995) and by altering the ApoE-HSPG complex formation and compromising the ability of ApoE to transport Aβ (Libeu et al. 2001, O’Callaghan et al. 2014, Kanekiyo & Bu 2009). Overall the studies combined support a model whereby neuronal secreted Aβ and astroglial produced proteoglycans form a feed forward loop to promote amyloid pathology through increased Aβ production and aggregation and reduced Aβ clearance. Consistent with this model, degradation of proteoglycans through enzymatic digestion of the GAG chains were shown to alleviate disease pathology in AD animal models (Jendresen et al. 2015). However, in light of the essential roles of proteoglycans in the CNS, further studies are needed to assess the therapeutic potential of targeting this pathway.

TGF-β

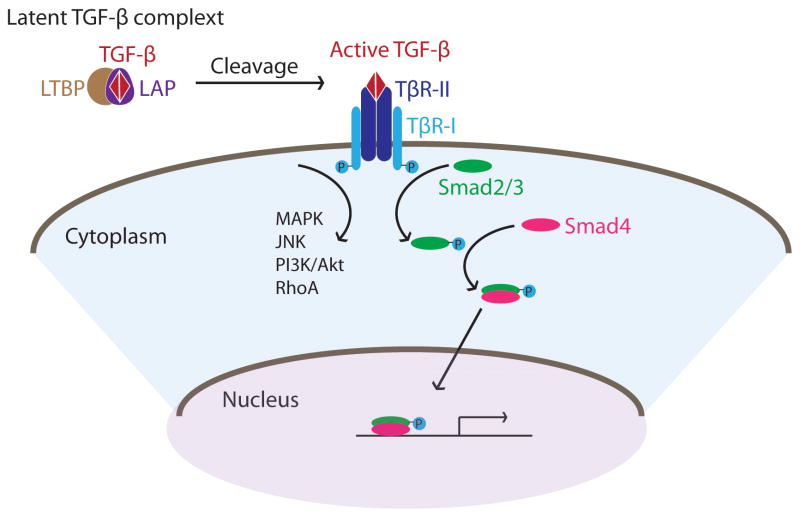

Transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) is a family of pleiotropic cytokines consisting of three members, TGF-β1, TGF-β2, and TGF-β3. They are secreted as a latent complex composed of a TGF-β dimer and a pro-peptide called latency associated peptide (LAP), which in most cases is associated with latent TGF-β binding protein (LTBP) to form a large latent complex in the extracellular matrix. Recognition of LTBP by cell-surface proteins and subsequent cleavage of LAP generates active and mature TGF-β. This process is tightly regulated to ensure proper activation of TGF-β signaling. On the cell surface, TGF-β type II receptor (TβR-II) binds to the activated TGF-β dimer and recruits type I receptor (TβR-I) to form a four-receptor complex (Figure 1). The TβR-II kinase domain, activated upon ligand binding, phosphorylates TβR-I which subsequently phosphorylates the transcriptional factor complex, the Smad2/3 complex. Phosphorylated Smad2/3 then binds to the common Smad4, translocates to nucleus and activates target gene expression. TβR-I also activates kinases, such as PI3K and MAPK, to trigger downstream pathways in a Smad independent manner (Zhang 2009) (Figure 1). The diverse outcomes of TGF-β activation are possibly determined by differences in the stimulators, the extracellular factors that TGF-β interacts with which in turn modifies its receptor binding affinities and the recruitment of different Smad proteins as well as other transcription factors.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of TGF-β signaling. LTBP: latent TGF-β binding protein; LAP: latency associated peptide; TβR-I and TβR-II: TGF-β receptor type I and II respectively.

In the CNS, neuron, glia and brain vasculature all express and respond to TGF-β (Flanders et al. 1991, Unsicker et al. 1991, Flanders et al. 1998). During embryonic development, the temporal and spatial expression of TGF-β tightly regulates neuronal survival, neurogenesis, synaptogenesis and gliogenesis (Bottner et al. 2000, Gomes et al. 2005) (Stipursky et al. 2014, Stipursky et al. 2012). These effects may depend on secreted astrocytic TGFβ and through both canonical and non-canonical signaling pathways (Yu et al. 2014, Diniz et al. 2014, Diniz et al. 2012). In particular, TGF-β1 deficiency causes neuronal death and microgliosis; these phenotypes can be reversed by astrocytic TGF-β1 expression (Brionne et al. 2003). Furthermore, astroglial expression of TGF-β mediates synaptic refinement during visual system maturation and, interestingly, this process was shown to be dependent on neuronal C1q (see “Complement” section) (Bialas & Stevens 2013). Finally, Schachtrup et al., reported that astrocytic TGF-β signaling promotes glial scar formation (Schachtrup et al. 2010). Interestingly, recent studies by the same group revealed that this pathway is regulated by γ-secretase cleavage of p75 neurotrophin receptor, raising the intriguing possibility that astroglial presenilin/γ-secretase activity may play a role in TGF-β-dependent neuron-glia communication (Schachtrup et al. 2015).

In healthy adult CNS, TGF-β2 and 3 are stably expressed. In contrast, TGF-β1 is absent or expressed at very low levels (Flanders et al. 1991, Koefer et al. 1995). Abnormal TGF-β1 hyperactivation has been detected in pathological conditions such as AD, Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and brain injury; astrocytes and microglia are the main source of TGF-β1 production (Phatnani et al. 2013, Endo et al. 2015, Finch et al. 1993, Morgan et al. 1993). Specific to AD, microglia and astrocytes secrete TGF-β upon Aβ stimulation (Tu et al. 2015, Tichauer & von Bernhardi 2012), consistent with increased levels of TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 in postmortem brain samples of AD (Grammas & Ovase 2002, Tarkowski et al. 2002, Malaguarnera et al. 2006, Swardfager et al. 2010, Flanders et al. 1995, Noguchi et al. 2010) and age-dependent TGF-β1 upregulation in AD mouse models (Wirths et al. 2010, Salins et al. 2008). Secreted TGF-β may directly engage neuronal response such as NFκB activation to promote cell survival as supplementing TGF-β protects neurons from Aβ toxicity (Ma et al. 2012, Chacon & Rodriguez-Tebar 2012), and this protective activity was shown to be antagonized by Aβ (Huang et al. 1998). Besides Aβ, neurofibrillary tangles may also interfere with neuronal response to TGF-β by sequestrating Smad proteins in the cytoplasm, eventually resulting in the death of tangle-bearing neurons (Chalmers & Love 2007). The expression of TGF-β type II receptor (TβR-II), which is mainly expressed by neurons, is reduced in AD brains (Tesseur et al. 2006). Supporting a beneficial role of TGF-β and TGF-β receptor signaling pathway, overexpression of a dominant negative TβR-II mutant promotes Aβ accumulation, dendritic loss and neurodegeneration in an AD mouse model (Tesseur et al. 2006). Conversely, supplementation of TGF-β1 rescued neurodegeneration in rats injected with Aβ42 (Chen et al. 2015). Besides a direct interaction with neurons, secreted TGF-β may also modulate neuronal physiology by participating microglial-mediated inflammatory responses (Huang et al. 2010, Cekanaviciute et al. 2014, Norden et al. 2014, Makwana et al. 2007). For instance, TGF-β enhances microglial Aβ uptake via Smad3-dependent modification of scavenger receptor expression (Tichauer & von Bernhardi 2012, Wyss-Coray et al. 2001). This could be the underlying mechanism by which astrocytic TGF-β1 expression reduces plaque pathology in APP transgenic mice (Wyss-Coray et al. 2001).

Nevertheless, negative association between TGF-β signaling and AD pathogenesis has also been reported (Hayes et al. 2013, Medeiros et al. 2013). In particular, TGF-β1-mediated neuronal signaling has been shown to potentiate APP transcription and Aβ production (Lesne et al. 2003, Docagne et al. 2004, Lahiri et al. 2003). Additionally TGF-β could contribute to AD through interacting with the cerebrovascular system (Wyss-Coray et al. 2000). Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) is a common feature in AD (Li et al. 2014). Transgenic mice expressing TGF-β1 in astrocytes develop CAA, and this phenotype may be attributed by the overexpression and accumulation of basement membrane proteins such as perlecan to facilitate amyloid deposition (Wyss-Coray et al. 1997, Wyss-Coray et al. 2000, Snow et al. 1994a). Lastly, TGF-β binds to ApoE in an isoform-dependent manner and this may indirectly influence Aβ clearance (Tesseur et al. 2009). Contrasting to the protective effects described above and supporting a detrimental role of heightened TGF-β signaling in AD pathogenesis, pharmacological inhibition of brain TGF-β was associated with alleviated AD pathology in mouse models (Sachdeva & Chopra 2015, Li et al. 2015, Zhang et al. 2014, Liu et al. 2014). Interestingly, blocking TGF-β signaling in peripheral macrophages was also reported to be efficacious in mitigating AD pathology (Town et al. 2008). Taken together, TGF-β signaling could play rather complicated and context-dependent activities during AD progression. Targeting the TGF-β pathway for potential therapeutic intervention will require further mechanistic and functional understanding.

NFκB

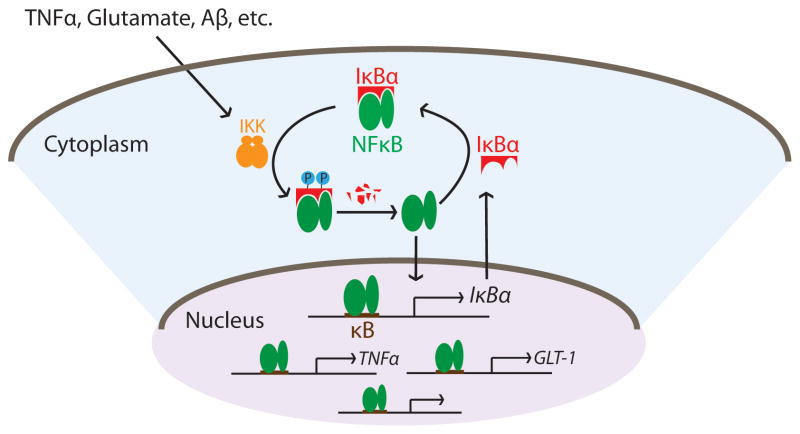

The nuclear factor-kappa B (NFκB) is a family of homo- or heterodimeric transcription factors present in nearly all cell types. NFκB is a master regulator of innate immunity that plays critical controls in various cellular processes such as proliferation, differentiation, survival, and apoptosis. NFκB is normally expressed in an inactive state in the cytoplasm where it is bound by its inhibitor protein family IκB. NFκB activation involves IκB phosphorylation and proteasome-mediated degradation leading to NFκB release. Once released, NFκB translocates to the nucleus and promotes gene expression upon binding to consensus κB DNA sites in promoter regions of target genes (Gilmore 2006). NFκB can be activated by a remarkable number of inducers such as intercellular mediators, bacterial or viral pathogens, reactive oxygen intermediates, and physical damage (Pahl 1999), which in turn regulates the expression of a growing list of target genes including those involved in innate and adaptive immunity, inflammatory responses, growth factors, and many others (http://www.bu.edu/nf-kb/gene-resources/target-genes/). The capability for certain inflammatory mediators, such as TNFα, IL-1β and IL-6, to act both as NFκB stimuli and downstream targets ensures augmentation of the immune responses. On the contrary, the fact that the principal NFκB inhibitor protein IκBα is a bona fide NFκB target allows formation of an elegant auto-inhibitory feedback loop to effectively terminate the pathway (Shim et al. 2011, Lian et al. 2012b, Chiao et al. 1994, Peng et al. 2010, Lian et al. 2015). These combined afford robust activation and precise regulation of NFκB-mediated responses (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the canonical NFκB signaling pathway. IKK: IκB kinase; GLT-1: glutamate type I transporter.

In the adult rodent brain, the most common form of the NFκB/IκB complex is a p50/p65 heterodimer bound by IκBα (Bakalkin et al. 1993, Meberg et al. 1996, Suzuki et al. 1997). NFκB can be induced in the CNS by a wide range of signals including neurotransmitters, neuropeptides and cytokines; neuronal NFκB expression has been reported to mediate morphogenesis, synaptogenesis, and learning and memory (Gutierrez & Davies 2011, Kaltschmidt & Kaltschmidt 2009, Maqbool et al. 2013). However, several recent studies raised the concern that some of the proposed neuronal NFκB detected may be caused by the contaminating glia or the non-specific nature of the antibodies (Herkenham et al. 2011, Lian et al. 2012a, Listwak et al. 2013, Massa et al. 2006, Mao et al. 2009). Since astrocytes and microglia possess robust NFκB responses, the precise contribution of neuronal vs. glial NFκB in neuronal development and function warrants further examination using cell-type specific assays and tools.

Substantial evidence supports a prominent role of astroglial NFκB in both physiological and pathological conditions. For instance, astrocytic expression of glutamate type I transporter (GLT-1) is essential in glutamate uptake and recycling (Rothstein et al. 1996, Robinson 1998, Ullensvang et al. 1997, Lehre & Danbolt 1998). Failure of glutamate homeostasis leads to excitotoxicity and neuronal cell death (Petr et al. 2015). NFκB is a positive regulator of GLT-1 (Gupta & Prasad 2014, Karki et al. 2013, Ghosh et al. 2011), and activity-dependent glutamate uptake through GLT-1 requires astroglial NFκB activation (Ghosh et al. 2011). As an NFκB inducer and downstream target, glial TNFα has been shown to mediate homeostatic synaptic scaling, although NFκB per se has not been explicitly implicated in this process (Stellwagen & Malenka 2006).

NFκB activity needs to be stringently controlled in the CNS to ensure normal neuronal development and function (Guerrini et al. 1997, Boersma et al. 2011, Meffert et al. 2003, Sylvie 2006). Aberrant NFκB activation has been observed in various neurodegenerative conditions, including Alzheimer’s disease (Kaltschmidt et al. 1997, Town et al. 2005, Mori et al. 2010), Parkinson’s disease (Hunot et al. 1997), and Huntington’s disease (Hsiao et al. 2013). In AD brains, p65 immunoreactivity is found to be enriched in neurons and glia in the vicinity of amyloid plaques (Kaltschmidt et al. 1997), indicating a possible NFκB activation by Aβ. Indeed, in vitro experiments demonstrated that NFκB activity can be induced by Aβ in neurons, astrocytes, and microglia (Kaltschmidt et al. 1997, Bales et al. 1998, Akama et al. 1998, Heurtaux et al. 2010, Carrero et al. 2012). As an transcription factor, activation of NFκB in reactive astrocytes induces expression changes of a large set of target genes resulting in both morphological ramifications and astrocytic functional changes (Frakes et al. 2014, Jayakumar et al. 2014, Wu et al. 2012, Corneveaux et al. 2010, Vincent et al. 2012, Hsieh et al. 2013, Walker-Caulfield et al. 2015). The astrocytic NFκB targets fall into many categories among which the inflammatory factors are most well understood. Those targets include nitrite oxide, cytokines, chemokines, etc. (Brambilla et al. 2014, Kim et al. 2012, Wang et al. 2013, Hiscott et al. 1993, Sparacio et al. 1992). Compromised astrocyte physiology by NFκB activation is associated with elevated mitochondrial oxidative metabolism, which restricts the supply of pyruvate substrates to neurons (Jiang & Cadenas 2014). The increased production of inflammatory factors also influences neurons directly by inducing neuronal oxidative stress and apoptosis (Akama et al. 1998, Wang et al. 2014a, Akama & Van Eldik 2000, Ye et al. 2013, Friedlander et al. 1996, Downen et al. 1999). Several studies showed that NFκB in astrocytes may regulate the integrity of the blood-brain-barrier essential for neuronal environmental homeostasis and compromised in AD (Park et al. 2014, Coelho-Santos et al. 2015)(Marques et al. 2013). Accordingly, inhibition of NFκB activation in AD models has been shown to ameliorate AD pathology and improve neuronal survival and cognitive function (Xuan et al. 2014, Lai et al. 2014, Medeiros et al. 2013, Shi et al. 2013, He et al. 2011, Brambilla et al. 2014, Jayakumar et al. 2014, Frakes et al. 2014, Brambilla et al. 2005), supporting the notion that NFκB antagonists may be therapeutically beneficial. Nevertheless, like other immune and inflammatory regulators, opposite effects have also been reported (Dvoriantchikova et al. 2009, Bracchi-Ricard et al. 2008), and the contrasting effects are likely attributed by the timing, duration and degree of the responses which require further investigation using spatially and temporally regulable tools and manipulations.

Complement

The complement pathway represents an evolutionarily conserved host defense and immune surveillance system known for its ability to recognize non-self pathogens and dying cells and eliminate them through phagocytosis or cell lysis (Holers 2014, Ricklin & Lambris 2013). Full complement activation involves concerted actions of over 30 proteins that participate in three distinct pathways: classical, alternative and mannose-binding-lection (MBL) (Reviewed by: Veerhuis et al. 2011, Yanamadala & Friedlander 2010, Zipfel & Skerka 2009). While the three pathways differ in their triggers, all converge on the cleavage of the central complement protein C3 by its convertase to C3a and C3b, which enables the conversion of C5 to C5a and C5b. While the C3 and C5 derivatives can mediate downstream signaling or phagocytic pathways through binding to their respective receptors, full complement activation requires the recruitment of other complement factors, including C7, C8, and C9, by C5b to form the terminal pore-forming complex termed the membrane attack complex (MAC). MAC insertion into the cell membrane induces cell death.

The complement pathway was originally assumed to be excluded from immune-privileged CNS and active only when the blood-brain-barrier is compromised. In recent years, however, expression of a full spectrum of complement proteins in the CNS has been detected (Shen et al. 1997, Singhrao et al. 1999, Walker & McGeer 1992, Thomas et al. 2000), where they have been implicated in both signaling and innate immune functions (Stephan et al. 2012). In particular, the C3a-C3aR interaction has been shown to regulate the migration and differentiation of neural stem cells through which it may influence adult neurogenesis (Shinjyo et al. 2009). A groundbreaking work by Stevens and colleagues revealed that astrocyte induced neuronal expression of proteins in the classical complement pathway, particularly C1q and C3, is required for proper elimination of unnecessary synapses during CNS development, and this is possibly regulated by neuronal activity and CR3-dependent microglial phagocytosis (Schafer et al. 2012, Stevens et al. 2007).

The complement pathway executes primarily inflammatory functions in the CNS. Astrocytes and microglia both express a large variety of complement factors as well as complement receptors (Bénard et al. 2008, Pisalyaput & Tenner 2008, Sayah et al. 2003, Veerhuis et al. 2011). Upon activation of complement receptors, glial cells change their profile to secrete proinflammatory cytokines, oxidative products, and also alter their phagocytosis ability (Farber et al. 2009, Fu et al. 2012, Sayah et al. 1999, Davoust et al. 1999, Griffiths et al. 2010, Sayah et al. 2003). In addition, cell lysis through the MAC has been proposed to mediate neuronal cell death associated with AD and other neurodegenerative conditions (Itagaki et al. 1994, Shen et al. 1998, Xiong et al. 2003).

Elevated complement expression at the RNA and protein levels have been consistently observed in brains of AD patients and mouse models (Fischer et al. 1995, Stoltzner et al. 2000, Walker & McGeer 1992, Zhou et al. 2008, Loeffler et al. 2008). The identification of clusterin (CLU or ApoJ), a potent regulator of complement activation, and complement receptor 1 (CR1) as genetic risk factors for AD lend support for a contributing rather than an associative role of complement activation in AD pathogenesis (Lambert et al. 2009, Harold et al. 2009). In vitro experiments demonstrated that Aβ can induce complement expression in neurons and glia (Fu et al. 2012, Haga et al. 1993, Carrero et al. 2012, Lian et al. 2015). However, the consequences of complement activation and the functional effects of complement blockade in vivo remain enigmatic. For example, Fonseca et al., reported that C1q deletion attenuated plaque load and synaptic protein loss in an AD mouse model (Fonseca et al. 2004); the same group also showed that application of C1q proved to be protective against Aβ toxicity (Pisalyaput & Tenner 2008). Likewise, both inhibition and activation of C5aR presented similar beneficial effects in AD mouse models: One study revealed that blocking C5aR by its antagonist reduced plaque pathology and glia activation in addition to improving behavioral performances (Fonseca et al. 2009), and another report documented that immunoglobulin treatment which induces C5aR activity resulted in improved synaptic plasticity and cognitive function (Gong et al. 2013). Moreover, inhibition of C3 by overexpressing the soluble complement receptor-related protein y (sCrry) or by C3 genetic ablation resulted in exacerbated Aβ pathology and late-age neurodegeneration (Maier et al. 2008, Fu et al. 2012, Wyss-Coray et al. 2002), implicating a detrimental effect of C3 inactivation. However, follow up studies by Lemere and colleagues revealed that, despite worsened amyloid pathology, C3 inhibition was associated with functional improvement and that the contrasting protective and neurotoxic effects appear to be age-dependent (Lemere and Zheng, personal communication). While the reasons for these apparently conflicting results remain to be resolved, it is clear that the complement-mediated responses are complex and context-dependent.

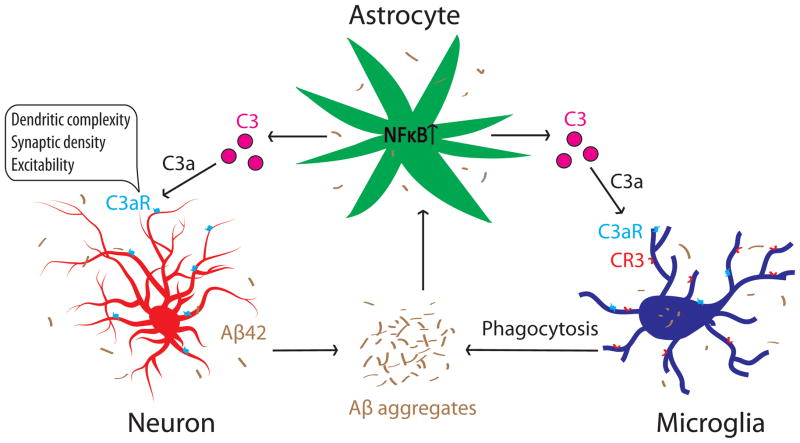

Whereas NFκB and complement can mediate neuronal function and innate immunity independently, our group recently revealed that they can also collaborate to regulate neuronal homeostasis and AD pathogenesis through an astroglia-neuron signaling pathway (Lian et al. 2015). Specifically, we found that C3 is an astroglial target of NFκB that is upregulated upon NFκB activation. C3 release from astrocytes acts through the neuronal C3a receptor (C3aR) to trigger aberrant intraneuronal calcium, leading to disrupted AMPA receptor trafficking, dendritic morphology and network function (Figure 3). Directly relevant to AD, we found that exposure to Aβ activates astroglial NFκB and C3 release in vitro and that C3aR antagonist treatment rescues cognitive impairment in APP transgenic mice (Lian et al. 2015). Our results support the therapeutic potential of C3aR antagonists for treating chronic neuroinflammation conditions accompanying AD and other neurodegenerative diseases. However, it is important to note that, although we demonstrated a direct astroglial C3 and neuronal C3aR interaction, the in vivo effects of the C3aR blockade are likely attributed by inhibiting the C3aR in all cell types, particularly microglia, where C3aR is highly expressed (Davoust et al. 1999, Martin et al. 2007) and where complement signaling has been shown to modulate Aβ phagocytosis (Fu et al. 2012). Taken together, we propose a complement-mediated intercellular crosstalk model in which neuronal overproduction of Aβ activates astroglial NFκB to elicit extracellular release of C3. This promotes a pathogenic cycle by which C3, in turn, interacts with neuronal and microglial C3aR to impair synaptic structure and function and Aβ phagocytosis, respectively, resulting in network dysfunction and AD pathogenesis (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

An NFκB- and C3-mediated astrocyte-neuron and astrocyte-microglia signaling network that mediates neuronal homeostasis and Alzheimer’s disease.

Conclusions

The last decade has witnessed an impressive growth of knowledge regarding the signaling pathways regulating glial biology and pathophysiology. We focus on some of the important examples in this review, namely the calcium, proteoglycan, TGFβ, NFκB, and complement pathways. It is clear that these factors play essential and multifaceted roles in maintaining neuronal homeostasis, and they impact neurodegenerative processes in a complex and context-dependent manner which may be dictated by their unique neuron-glia signaling profiles or the crosstalk among these pathways. While we attempt to provide a comprehensive and unbiased summary of the wealth of information contained in the published literature, it is important to note that interpretation of the findings should take system and technical limitations into consideration. In particular, many of the studies discussed in this review use in vitro systems or mixed cell-type analysis, both of which do not offer the spatial and temporal resolution needed to decipher the cell-type specific contribution to network function and dysfunction. Many fundamental questions remain within the realm of astrocytes. For example, how many types of astrocytes are there in the CNS? What are their morphological and molecular signatures, and how do these signatures alter during aging and in pathological conditions? Do different types of astrocytes exhibit distinct responses to brain insults, and do these in turn convey distinct neuron-glia signaling pathways? With the development of sophisticated cell-type specific targeting and genetic and functional manipulations combined with powerful imaging technology, we are now poised to perform molecular, biochemical, morphological and functional characterizations at subcellular, cellular and network levels as well as under physiological and disease relevant context. These will not only reveal unprecedented insights into the signaling mechanisms underlying glial pathobiology and neuron-glia interaction, but also provide therapeutic understanding on targeting neuron-glia interaction for AD and other neurodegenerative diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Allysa Cole for the proofreading and editing of the manuscript. The present study was supported by grants from NIH (AG032051, AG020670 and NS076117).

Abbreviation list

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- C3aR

C3a receptor

- C5aR

C5a receptor

- CAA

cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- CGSP

Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan

- CLU

clusterin

- CNS

central nervous system

- CR1

complement receptor 1

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- GLT-1

glutamate type I transporter

- GSG

glycosaminoglycan

- GSH

glutathione

- HSPG

heparin sulfate proteoglycan

- IκB

inhibitor protein κB

- LAP

latency associated peptide

- LTBP

latent TGF-β binding protein

- MAC

membrane attack complex

- MBL

mannose-binding-lection

- NFκB

nuclear factor-kappa B

- sCry

soluble complement receptor-related protein y

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor β

- TβR

TGF-β receptor

Footnotes

conflict of interest disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Abramov AY, Canevari L, Duchen MR. Changes in intracellular calcium and glutathione in astrocytes as the primary mechanism of amyloid neurotoxicity. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5088–5095. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-05088.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramov AY, Canevari L, Duchen MR. Calcium signals induced by amyloid beta peptide and their consequences in neurons and astrocytes in culture. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1742:81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akama KT, Albanese C, Pestell RG, Van Eldik LJ. Amyloid β-peptide stimulates nitric oxide production in astrocytes through an NFκB-dependent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:5795–5800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akama KT, Van Eldik LJ. β-amyloid stimulation of inducible nitric-oxide synthase in astrocytes is interleukin-1β- and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFalpha)-dependent, and involves a TNFalpha receptor-associated factor- and NFκB-inducing kinase-dependent signaling mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:7918–7924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.7918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberdi E, Wyssenbach A, Alberdi M, Sánchez-Gómez MV, Cavaliere F, Rodríguez JJ, Verkhratsky A, Matute C. Ca2+-dependent endoplasmic reticulum stress correlates with astrogliosis in oligomeric amyloid β-treated astrocytes and in a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Cell. 2013;12:292–302. doi: 10.1111/acel.12054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen NJ, Barres BA. Neuroscience: Glia - more than just brain glue. Nature. 2009;457:675–677. doi: 10.1038/457675a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen NJ, Bennett ML, Foo LC, Wang GX, Chakraborty C, Smith SJ, Barres BA. Astrocyte glypicans 4 and 6 promote formation of excitatory synapses via GluA1 AMPA receptors. Nature. 2012;486:410–414. doi: 10.1038/nature11059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MA, Ao Y, Sofroniew MV. Heterogeneity of reactive astrocytes. Neuroscience Letters. 2014;565:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araque A, Carmignoto G, Haydon PG, Oliet SH, Robitaille R, Volterra A. Gliotransmitters travel in time and space. Neuron. 2014;81:728–739. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armato U, Bonafini C, Chakravarthy B, Pacchiana R, Chiarini A, Whitfield JF, Dal Prà I. The calcium-sensing receptor: A novel Alzheimer’s disease crucial target? Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2012;322:137–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2012.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelsen PH, Komatsu H, Murray IVJ. Oxidative Stress and Cell Membranes in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer's Disease. Physiology. 2011;26:54–69. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00024.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakalkin G, Yakovleva T, Terenius L. NF-κB-like factors in the murine brain. Developmentally-regulated and tissue-specific expression. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1993;20:137–146. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(93)90119-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bales KR, Du Y, Dodel RC, Yan GM, Hamilton-Byrd E, Paul SM. The NF-κB/Rel family of proteins mediates Aβ-induced neurotoxicity and glial activation. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1998;57:63–72. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandtlow CE, Zimmermann DR. Proteoglycans in the developing brain: new conceptual insights for old proteins. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:1267–1290. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.4.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barres BA. The mystery and magic of glia: a perspective on their roles in health and disease. Neuron. 2008;60:430–440. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellucci C. Differences in extracellular matrix production and basic fibroblast growth factor response in skin fibroblasts from sporadic and familial Alzheimer’s disease. Molecular medicine (Cambridge, Mass) 2007;13:542–550. doi: 10.2119/2007-00034.Bellucci. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bénard M, Raoult E, Vaudry D, Leprince J, Falluel-Morel A, Gonzalez BJ, Galas L, Vaudry H, Fontaine M. Role of complement anaphylatoxin receptors (C3aR, C5aR) in the development of the rat cerebellum. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:3767–3774. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezprozvanny I. Amyloid goes global. Science signaling. 2009;2:pe16. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.263pe16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezprozvanny I, Hiesinger PR. The synaptic maintenance problem: membrane recycling, Ca2+ homeostasis and late onset degenerationYang. Mol Neurodegener. 2013;8:23. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-8-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialas AR, Stevens B. TGF-beta signaling regulates neuronal C1q expression and developmental synaptic refinement. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1773–1782. doi: 10.1038/nn.3560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Boersma MCH, Dresselhaus EC, De Biase LM, Mihalas AB, Bergles DE, Meffert MK. A requirement for nuclear factor-κB in developmental and plasticity-associated synaptogenesis. J Neurosci. 2011;31:5414–5425. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2456-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottner M, Krieglstein K, Unsicker K. The transforming growth factor-betas: structure, signaling, and roles in nervous system development and functions. J Neurochem. 2000;75:2227–2240. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracchi-Ricard V, Brambilla R, Levenson J, Hu WH, Bramwell A, Sweatt JD, Green EJ, Bethea JR. Astroglial nuclear factor-κB regulates learning and memory and synaptic plasticity in female mice. J Neurochem. 2008;104:611–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury EJ, Moon LDF, Popat RJ, King VR, Bennett GS, Patel PN, Fawcett JW, McMahon SB. Chondroitinase ABC promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Nature. 2002;416:636–640. doi: 10.1038/416636a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brambilla R, Bracchi-Ricard V, Hu WH, Frydel B, Bramwell A, Karmally S, Green EJ, Bethea JR. Inhibition of astroglial nuclear factor kappaB reduces inflammation and improves functional recovery after spinal cord injury. J Exp Med. 2005;202:145–156. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brambilla R, Morton PD, Ashbaugh JJ, Karmally S, Lambertsen KL, Bethea JR. Astrocytes play a key role in EAE pathophysiology by orchestrating in the CNS the inflammatory response of resident and peripheral immune cells and by suppressing remyelination. Glia. 2014;62:452–467. doi: 10.1002/glia.22616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brionne TC, Tesseur I, Masliah E, Wyss-Coray T. Loss of TGF-beta 1 leads to increased neuronal cell death and microgliosis in mouse brain. Neuron. 2003;40:1133–1145. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00766-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buée L, Ding W, Anderson JP, et al. Binding of vascular heparan sulfate proteoglycan to Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor protein is mediated in part by the N-terminal region of A4 peptide. Brain Research. 1993;627:199–204. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90321-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cafferty WBJ, Yang SH, Duffy PJ, Li S, Strittmatter SM. Functional Axonal Regeneration through Astrocytic Scar Genetically Modified to Digest Chondroitin Sulfate Proteoglycans. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:2176–2185. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5176-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canning DR, McKeon RJ, DeWitt DA, Perry G, Wujek JR, Frederickson RCA, Silver J. β-Amyloid of Alzheimer’s Disease Induces Reactive Gliosis That Inhibits Axonal Outgrowth. Experimental Neurology. 1993;124:289–298. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1993.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrero I, Gonzalo MR, Martin B, Sanz-Anquela JM, Arevalo-Serrano J, Gonzalo-Ruiz A. Oligomers of beta-amyloid protein (Abeta1–42) induce the activation of cyclooxygenase-2 in astrocytes via an interaction with interleukin-1beta, tumour necrosis factor-alpha, and a nuclear factor kappa-B mechanism in the rat brain. Exp Neurol. 2012;236:215–227. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cekanaviciute E, Fathali N, Doyle KP, Williams AM, Han J, Buckwalter MS. Astrocytic transforming growth factor-beta signaling reduces subacute neuroinflammation after stroke in mice. Glia. 2014;62:1227–1240. doi: 10.1002/glia.22675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacon PJ, Rodriguez-Tebar A. Increased expression of the homologue of enhancer-of-split 1 protects neurons from beta amyloid neurotoxicity and hints at an alternative role for transforming growth factor beta1 as a neuroprotector. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2012;4:31. doi: 10.1186/alzrt134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers KA, Love S. Neurofibrillary tangles may interfere with Smad 2/3 signaling in neurons. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66:158–167. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e3180303b93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JH, Ke KF, Lu JH, Qiu YH, Peng YP. Protection of TGF-β1 against Neuroinflammation and Neurodegeneration in Aβ<sub>1–42</sub>-Induced Alzheimer’s Disease Model Rats. PloS one. 2015;10:e0116549. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiao PJ, Miyamoto S, Verma IM. Autoregulation of I kappa B alpha activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:28–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiarini A, Dal Pra I, Marconi M, Chakravarthy B, Whitfield JF, Armato U. Calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) in human brain’s pathophysiology: roles in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2009;10:317–326. doi: 10.2174/138920109787847501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo YS, Johnson GV, MacDonald M, Detloff PJ, Lesort M. Mutant huntingtin directly increases susceptibility of mitochondria to the calcium-induced permeability transition and cytochrome c release. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1407–1420. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow SK, Yu D, MacDonald CL, Buibas M, Silva GA. Amyloid β-peptide directly induces spontaneous calcium transients, delayed intercellular calcium waves and gliosis in rat cortical astrocytes. ASN neuro. 2010;2:e00026. doi: 10.1042/AN20090035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson HC, Belting M. Heparan sulfate proteoglycan as a cell-surface endocytosis receptor. Matrix Biology. 2014;35:51–55. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RA. Synergistic signaling from extracellular matrix-growth factor complexes. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1354–1355. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarris HJ, Nurcombe V, Small DH, Beyreuther K, Masters CL. Secretion of nerve growth factor from septum stimulates neurite outgrowth and release of the amyloid protein precursor of Alzheimer’s disease from hippocampal explants. J Neurosci Res. 1994;38:248–258. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490380303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho-Santos V, Leitao RA, Cardoso FL, Palmela I, Rito M, Barbosa M, Brito MA, Fontes-Ribeiro CA, Silva AP. The TNF-alpha/NF-kappaB signaling pathway has a key role in methamphetamine-induced blood-brain barrier dysfunction. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2015;35:1260–1271. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2015.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corneveaux JJ, Myers AJ, Allen AN, et al. Association of CR1, CLU and PICALM with Alzheimer’s disease in a cohort of clinically characterized and neuropathologically verified individuals. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:3295–3301. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui H, Freeman C, Jacobson GA, Small DH. Proteoglycans in the central nervous system: role in development, neural repair, and Alzheimer’s disease. IUBMB Life. 2013;65:108–120. doi: 10.1002/iub.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui H, Hung AC, Freeman C, Narkowicz C, Jacobson GA, Small DH. Size and sulfation are critical for the effect of heparin on APP processing and Abeta production. J Neurochem. 2012;123:447–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davoust N, Jones J, Stahel PF, Ames RS, Barnum SR. Receptor for the C3a anaphylatoxin is expressed by neurons and glial cells. Glia. 1999;26:201–211. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199905)26:3<201::aid-glia2>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Prete D, Checler F, Chami M. Ryanodine receptors: physiological function and deregulation in Alzheimer disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2014;9:21. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-9-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delekate A, Fuchtemeier M, Schumacher T, Ulbrich C, Foddis M, Petzold GC. Metabotropic P2Y1 receptor signalling mediates astrocytic hyperactivity in vivo in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5422. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demuro A, Parker I. Cytotoxicity of intracellular abeta42 amyloid oligomers involves Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum by stimulated production of inositol trisphosphate. J Neurosci. 2013;33:3824–3833. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4367-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng YP, Sun Y, Hu L, Li ZH, Xu QM, Pei YL, Huang ZH, Yang ZG, Chen C. Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans impede myelination by oligodendrocytes after perinatal white matter injury. Experimental Neurology. 2015;269:213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWitt DA, Silver J, Canning DR, Perry G. Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans are associated with the lesions of Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Neurol. 1993;121:149–152. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1993.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diniz LP, Almeida JC, Tortelli V, et al. Astrocyte-induced synaptogenesis is mediated by transforming growth factor beta signaling through modulation of D-serine levels in cerebral cortex neurons. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:41432–41445. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.380824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diniz LP, Tortelli V, Garcia MN, et al. Astrocyte transforming growth factor beta 1 promotes inhibitory synapse formation via CaM kinase II signaling. Glia. 2014;62:1917–1931. doi: 10.1002/glia.22713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docagne F, Gabriel C, Lebeurrier N, Lesne S, Hommet Y, Plawinski L, Mackenzie ET, Vivien D. Sp1 and Smad transcription factors co-operate to mediate TGF-beta-dependent activation of amyloid-beta precursor protein gene transcription. Biochem J. 2004;383:393–399. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dow KE, Wang W. Cell biology of astrocyte proteoglycans. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 1998;54:567–581. doi: 10.1007/s000180050185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downen M, Amaral TD, Hua LL, Zhao ML, Lee SC. Neuronal death in cytokine-activated primary human brain cell culture: role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Glia. 1999;28:114–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvoriantchikova G, Barakat D, Brambilla R, Agudelo C, Hernandez E, Bethea JR, Shestopalov VI, Ivanov D. Inactivation of astroglial NF-κB promotes survival of retinal neurons following ischemic injury. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:175–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06814.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo F, Komine O, Fujimori-Tonou N, et al. Astrocyte-Derived TGF-β1 Accelerates Disease Progression in ALS Mice by Interfering with the Neuroprotective Functions of Microglia and T Cells. Cell Reports. 2015;11:592–604. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faissner A, Pyka M, Geissler M, Sobik T, Frischknecht R, Gundelfinger ED, Seidenbecher C. Contributions of astrocytes to synapse formation and maturation — Potential functions of the perisynaptic extracellular matrix. Brain Research Reviews. 2010;63:26–38. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farber K, Cheung G, Mitchell D, Wallis R, Weihe E, Schwaeble W, Kettenmann H. C1q, the recognition subcomponent of the classical pathway of complement, drives microglial activation. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:644–652. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhy Tselnicker I, Boisvert MM, Allen NJ. The role of neuronal versus astrocyte-derived heparan sulfate proteoglycans in brain development and injury. Biochemical Society transactions. 2014;42:1263–1269. doi: 10.1042/BST20140166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filous AR, Tran A, Howell CJ, et al. Entrapment via synaptic-like connections between NG2 proteoglycan+ cells and dystrophic axons in the lesion plays a role in regeneration failure after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2014;34:16369–16384. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1309-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch CE, Laping NJ, Morgan TE, Nichols NR, Pasinetti GM. TGF-beta 1 is an organizer of responses to neurodegeneration. J Cell Biochem. 1993;53:314–322. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240530408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer B, Schmoll H, Riederer P, Bauer J, Platt D, Popa-Wagner A. Complement C1q and C3 mRNA expression in the frontal cortex of Alzheimer’s patients. J Mol Med. 1995;73:465–471. doi: 10.1007/BF00202265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders KC, Lippa CF, Smith TW, Pollen DA, Sporn MB. Altered expression of transforming growth factor-beta in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1995;45:1561–1569. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.8.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders KC, Ludecke G, Engels S, Cissel DS, Roberts AB, Kondaiah P, Lafyatis R, Sporn MB, Unsicker K. Localization and actions of transforming growth factor-beta’s in the embryonic nervous system. Development. 1991;113:183–191. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders KC, Ren RF, Lippa CF. Transforming growth factor-betas in neurodegenerative disease. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;54:71–85. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(97)00066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca MI, Ager RR, Chu SH, Yazan O, Sanderson SD, LaFerla FM, Taylor SM, Woodruff TM, Tenner AJ. Treatment with a C5aR antagonist decreases pathology and enhances behavioral performance in murine models of Alzheimer’s disease. J Immunol. 2009;183:1375–1383. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca MI, Zhou J, Botto M, Tenner AJ. Absence of C1q leads to less neuropathology in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6457–6465. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0901-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frakes AE, Ferraiuolo L, Haidet-Phillips AM, et al. Microglia induce motor neuron death via the classical NF-κB pathway in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuron. 2014;81:1009–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedlander RM, Gagliardini V, Rotello RJ, Yuan J. Functional role of interleukin 1 beta (IL-1 beta) in IL-1 beta-converting enzyme-mediated apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1996;184:717–724. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H, Liu B, Frost JL, et al. Complement component C3 and complement receptor type 3 contribute to the phagocytosis and clearance of fibrillar Aβ by microglia. Glia. 2012;60:993–1003. doi: 10.1002/glia.22331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garden GA, La Spada AR. Intercellular (mis)communication in neurodegenerative disease. Neuron. 2012;73:886–901. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garwood C, Faizullabhoy A, Wharton SB, et al. Calcium dysregulation in relation to Alzheimer-type pathology in the ageing brain. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2013;39:788–799. doi: 10.1111/nan.12033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geissler M, Gottschling C, Aguado A, Rauch U, Wetzel CH, Hatt H, Faissner A. Primary Hippocampal Neurons, Which Lack Four Crucial Extracellular Matrix Molecules, Display Abnormalities of Synaptic Structure and Function and Severe Deficits in Perineuronal Net Formation. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2013;33:7742–7755. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3275-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geneste A, Guillaume YC, Magy-Bertrand N, Lethier L, Gharbi T, Andre C. The protease activity of transthyretin reverses the effect of pH on the amyloid-beta protein/heparan sulfate proteoglycan interaction: a biochromatographic study. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2014;97:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2014.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh M, Yang Y, Rothstein JD, Robinson MB. Nuclear factor-kappaB contributes to neuron-dependent induction of glutamate transporter-1 expression in astrocytes. J Neurosci. 2011;31:9159–9169. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0302-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giamanco KA, Matthews RT. Deconstructing the perineuronal net: Cellular contributions and molecular composition of the neuronal extracellular matrix. Neuroscience. 2012;218:367–384. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore TD. Introduction to NF-κB: players, pathways, perspectives. Oncogene. 2006;25:6680–6684. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes FC, de Sousa VO, Romao L. Emerging roles for TGF-beta1 in nervous system development. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2005;23:413–424. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong B, Pan Y, Zhao W, et al. IVIG immunotherapy protects against synaptic dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease through complement anaphylatoxin C5a-mediated AMPA-CREB-C/EBP signaling pathway. Mol Immunol. 2013;56:619–629. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2013.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grammas P, Ovase R. Cerebrovascular transforming growth factor-beta contributes to inflammation in the Alzheimer’s disease brain. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:1583–1587. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)61105-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths MR, Gasque P, Neal JW. The Regulation of the CNS Innate Immune Response Is Vital for the Restoration of Tissue Homeostasis (Repair) after Acute Brain Injury: A Brief Review. International Journal of Inflammation. 2010;2010 doi: 10.4061/2010/151097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro R, Bras J, Hardy J. SnapShot: genetics of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell. 2013;155:968–968.e961. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrini L, Molteni A, Wirth T, Kistler B, Blasi F. Glutamate-dependent activation of NF-κB during mouse cerebellum development. J Neurosci. 1997;17:6057–6063. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-16-06057.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q, Wang Z, Li H, Wiese M, Zheng H. APP physiological and pathophysiological functions: insights from animal models. Cell Res. 2012;22:78–89. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta-Bansal R, Frederickson RCA, Brunden KR. Proteoglycan-mediated inhibition of Aβ proteolysis: A potential cause of senile plaque accumulation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:18666–18671. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.31.18666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta RK, Prasad S. Differential regulation of GLT-1/EAAT2 gene expression by NF-kappaB and N-myc in male mouse brain during postnatal development. Neurochemical research. 2014;39:150–160. doi: 10.1007/s11064-013-1200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez H, Davies AM. Regulation of neural process growth, elaboration and structural plasticity by NF-κB. Trends in Neurosciences. 2011;34:316–325. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haga S, Ikeda K, Sato M, Ishii T. Synthetic Alzheimer amyloid beta/A4 peptides enhance production of complement C3 component by cultured microglial cells. Brain Res. 1993;601:88–94. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91698-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halassa MM, Fellin T, Haydon PG. The tripartite synapse: roles for gliotransmission in health and disease. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamid R, Kilger E, Willem M, et al. Amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain modulates cellular calcium homeostasis and ATP content. J Neurochem. 2007;102:1264–1275. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harold D, Abraham R, Hollingworth P, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and PICALM associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1088–1093. doi: 10.1038/ng.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashioka S, Klegeris A, McGeer PL. Inhibition of human astrocyte and microglia neurotoxicity by calcium channel blockers. Neuropharmacology. 2012;63:685–691. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes CD, Dey D, Palavicini JP, Wang H, Patkar KA, Minond D, Nefzi A, Lakshmana MK. Striking reduction of amyloid plaque burden in an Alzheimer’s mouse model after chronic administration of carmustine. BMC Med. 2013;11:81. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He FQ, Qiu BY, Zhang XH, Li TK, Xie Q, Cui DJ, Huang XL, Gan HT. Tetrandrine attenuates spatial memory impairment and hippocampal neuroinflammation via inhibiting NF-κB activation in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease induced by amyloid-β(1–42) Brain Res. 2011;1384:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.01.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneka MT, Carson MJ, Khoury JE, et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. The Lancet Neurology. 2015;14:388–405. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)70016-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensley K. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease: mechanisms, pathologic consequences, and potential for therapeutic manipulation. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;21:1–14. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herkenham M, Rathore P, Brown P, Listwak S. Cautionary notes on the use of NF-κB p65 and p50 antibodies for CNS studies. Journal of neuroinflammation. 2011;8:141. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertz L. Intercellular metabolic compartmentation in the brain: past, present and future. Neurochem Int. 2004;45:285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2003.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heurtaux T, Michelucci A, Losciuto S, Gallotti C, Felten P, Dorban G, Grandbarbe L, Morga E, Heuschling P. Microglial activation depends on β-amyloid conformation: role of the formylpeptide receptor 2. J Neurochem. 2010;114:576–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks JB, Lai Y, Sheng W, Yang X, Zhu D, Sun GY, Lee JC. Amyloid-beta peptide induces temporal membrane biphasic changes in astrocytes through cytosolic phospholipase A2. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:2512–2519. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiscott J, Marois J, Garoufalis J, et al. Characterization of a functional NF-κB site in the human interleukin 1 β promoter: evidence for a positive autoregulatory loop. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6231–6240. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.6231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holers VM. Complement and its receptors: new insights into human disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:433–459. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoos MD, Vitek MP, Ridnour LA, Wilson J, Jansen M, Everhart A, Wink DA, Colton CA. The impact of human and mouse differences in NOS2 gene expression on the brain’s redox and immune environment. Mol Neurodegener. 2014;9:50. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-9-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao HY, Chen YC, Chen HM, Tu PH, Chern Y. A critical role of astrocyte-mediated nuclear factor-κB-dependent inflammation in Huntington’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:1826–1842. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HL, Lin CC, Hsiao LD, Yang CM. High glucose induces reactive oxygen species-dependent matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression and cell migration in brain astrocytes. Mol Neurobiol. 2013;48:601–614. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8442-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SS, Huang FW, Xu J, Chen S, Hsu CY, Huang JS. Amyloid β-Peptide Possesses a Transforming Growth Factor-β Activity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:27640–27644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang WC, Yen FC, Shie FS, Pan CM, Shiao YJ, Yang CN, Huang FL, Sung YJ, Tsay HJ. TGF-beta1 blockade of microglial chemotaxis toward Abeta aggregates involves SMAD signaling and down-regulation of CCL5. J Neuroinflammation. 2010;7:28. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-7-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunot S, Brugg B, Ricard D, Michel PP, Muriel MP, Ruberg M, Faucheux BA, Agid Y, Hirsch EC. Nuclear translocation of NF-κB is increased in dopaminergic neurons of patients with parkinson disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:7531–7536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliff JJ, Lee H, Yu M, Feng T, Logan J, Nedergaard M, Benveniste H. Brain-wide pathway for waste clearance captured by contrast-enhanced MRI. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1299–1309. doi: 10.1172/JCI67677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliff JJ, Wang M, Liao Y, et al. A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid beta. Science translational medicine. 2012;4:147ra111. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iozzo RV, Schaefer L. Proteoglycan form and function: A comprehensive nomenclature of proteoglycans. Matrix Biol. 2015;42:11–55. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itagaki S, Akiyama H, Saito H, McGeer PL. Ultrastructural localization of complement membrane attack complex (MAC)-like immunoreactivity in brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 1994;645:78–84. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91640-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayakumar AR, Tong XY, Ruiz-Cordero R, Bregy A, Bethea JR, Bramlett HM, Norenberg MD. Activation of NF-κB mediates astrocyte swelling and brain edema in traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2014 doi: 10.1089/neu.2013.3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jendresen CB, Cui H, Zhang X, Vlodavsky I, Nilsson LN, Li JP. Overexpression of heparanase lowers the amyloid burden in amyloid-beta precursor protein transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:5053–5064. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.600569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T, Cadenas E. Astrocytic metabolic and inflammatory changes as a function of age. Aging Cell. 2014;13:1059–1067. doi: 10.1111/acel.12268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston JM, Burnett P, Thomas AP, Tezapsidis N. Calcium oscillations in type-1 astrocytes, the effect of a presenilin 1 (PS1) mutation. Neurosci Lett. 2006;395:159–164. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.10.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltschmidt B, Kaltschmidt C. NF-kappaB in the nervous system. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a001271. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltschmidt B, Uherek M, Volk B, Baeuerle PA, Kaltschmidt C. Transcription factor NF-κB is activated in primary neurons by amyloid β peptides and in neurons surrounding early plaques from patients with Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:2642–2647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanekiyo T, Bu G. Receptor-associated protein interacts with amyloid-beta peptide and promotes its cellular uptake. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:33352–33359. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.015032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SS, Jeraldo PR, Kurti A, et al. Diet and exercise orthogonally alter the gut microbiome and reveal independent associations with anxiety and cognition. Mol Neurodegener. 2014;9:36. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-9-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi-Abdolrezaee S, Billakanti R. Reactive astrogliosis after spinal cord injury-beneficial and detrimental effects. Mol Neurobiol. 2012;46:251–264. doi: 10.1007/s12035-012-8287-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karki P, Webb A, Smith K, Lee K, Son DS, Aschner M, Lee E. cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) and nuclear factor kappaB mediate the tamoxifen-induced up-regulation of glutamate transporter 1 (GLT-1) in rat astrocytes. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:28975–28986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.483826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal V, Koeberle PD, Wang Y, Schlichter LC. The Ca2+-activated K+ channel KCNN4/KCa3.1 contributes to microglia activation and nitric oxide-dependent neurodegeneration. J Neurosci. 2007;27:234–244. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3593-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MS, Takahashi T, Lee JY, Hwang GW, Naganuma A. Methylmercury induces CCL2 expression through activation of NF-κB in human 1321N1 astrocytes. J Toxicol Sci. 2012;37:1275–1278. doi: 10.2131/jts.37.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Turnbull J, Guimond S. Extracellular matrix and cell signalling: the dynamic cooperation of integrin, proteoglycan and growth factor receptor. Journal of Endocrinology. 2011;209:139–151. doi: 10.1530/JOE-10-0377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koefer R, Streit WJ, Toyka KV, Kreutzberg GW, Hartung HP. Transforming growth factor-β1: A lesion-associated cytokine of the nervous system. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 1995;13:331–339. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(94)00074-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchibhotla KV, Goldman ST, Lattarulo CR, Wu HY, Hyman BT, Bacskai BJ. Abeta plaques lead to aberrant regulation of calcium homeostasis in vivo resulting in structural and functional disruption of neuronal networks. Neuron. 2008;59:214–225. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchibhotla KV, Lattarulo CR, Hyman BT, Bacskai BJ. Synchronous hyperactivity and intercellular calcium waves in astrocytes in Alzheimer mice. Science. 2009;323:1211–1215. doi: 10.1126/science.1169096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukreja L, Kujoth GC, Prolla TA, Van Leuven F, Vassar R. Increased mtDNA mutations with aging promotes amyloid accumulation and brain atrophy in the APP/Ld transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2014;9:16. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-9-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFerla FM. Calcium dyshomeostasis and intracellular signalling in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:862–872. doi: 10.1038/nrn960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri DK, Chen D, Vivien D, Ge YW, Greig NH, Rogers JT. Role of cytokines in the gene expression of amyloid beta-protein precursor: identification of a 5’-UTR-binding nuclear factor and its implications in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2003;5:81–90. doi: 10.3233/jad-2003-5203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]