Abstract

Objectives

The objectives were to synthesize cumulative findings across three critical ethnographic, community-partnered studies in the southwestern United States and to describe the process of meta-ethnography for that analysis.

Design

The meta-ethnography followed the design of Noblit and Hare for constructing an analysis of composite data, informed by community-based participatory research and Stringer’s ethnographic strategies of Look-Think-Act.

Sample

The three studies occurred in rural settings of Colorado and New Mexico, engaging 129 total participants, along with community organizations and agencies as partners.

Methods

Methods consisted of detailed review of each original study, mapping of major concepts and themes, and general analysis, interpretation, and synthesis across the studies.

Results

Overall themes were: health is the capacity to care for oneself and do work, meaningful relationships are key in health care interactions, patterns of discrimination persist in rural settings, poor literacy and health literacy are barriers, and food insecurity is a growing concern for older rural adults.

Conclusions

Resolutions involve practice, policy and research and must incorporate all stakeholder groups in rural settings; a participatory approach is critical to prioritize and impact existing inequities; and work is needed to extend education and understanding of multiple cultures, groups, customs, and rural contexts.

Keywords: elderly, health disparities, migrant workers, minority health, participatory action research, qualitative research, rural health, transcultural nursing

The purpose of this article is twofold: (1) to summarize and synthesize cumulative findings across three critical ethnographic/community partnership studies that occurred in Colorado (CO) and New Mexico (NM); and (2) to describe the process of meta-ethnography as a strategy for that analysis. A meta-study is defined as an analysis of previous findings from multiple related studies, followed by a synthesis and integration of that composite work (Paterson, Thorne, Canam, & Jillings, 2001). My approach echoed that of Noblit and Hare (1988), who examined the merged data for points of divergence and convergence and defined meta-ethnography as “the synthesis of interpretive research” (p. 10). I support the Noblit–Hare (1988) argument that the outcome of a meta-ethnography is focused “on constructing interpretations, not analyses. To our way of thinking, the synthesis of qualitative research should be as interpretive as any ethnographic account” (p. 11). This is interpretive work because it seeks “an explanation for social or cultural events based upon the perspectives and experiences of the people being studied” (p. 12), documenting what Geertz (1973) called “webs of significance” (p. 5), not simply analytic process.

Conceptual Basis and Background

The conceptual foundations for the three studies blended community-based participatory research (CBPR), Stringer’s (2014) ethnographic concepts of Looking-Thinking-Acting, and my clinical practice in northeast CO migrant worker settings and American Indian/multicultural NM communities, where I applied principles of public health science and community health nursing to the care of rural families. Those principles included a focus on community-dwelling populations, especially vulnerable groups; the importance of community contexts and partnerships; health-promoting and disease-preventing interventions; and application of the nursing process to community-as-client/partner, including relevant organizations, policies, resources, research, and applying knowledge arising from nursing, social science, and public health science (American Public Health Association, Public Health Nursing Section, 2013; Stanhope & Lancaster, 2010; Truglio-Londrigan & Lewenson, 2011).

Minkler and Wallerstein (2008) described critical attributes for CBPR, drawn from across the literature and philosophic traditions of critical and social sciences. The focus is on social justice, health equity, power dynamics, and demographic patterns of health disparities: “It [CBPR] is participatory; it is cooperative, engaging community members and researchers in a joint process in which both contribute equally; it is a co-learning process; it involves systems development and local community capacity-building; it is an empowering process through which participants can increase control over their lives; it achieves a balance between research and action” (p. 9). Describing CBPR as “democratic, equitable, liberating and life enhancing” (pp. 14–15), Stringer (2014) labeled it action research, believing that “all people affected by or having an effect on an issue should be involved in the process of inquiry” (p. xv). He defined the researcher’s role as that of facilitator, listener, and catalyst. Stringer’s basic action research strategy or approach is as follows:

Looking— an early, exploratory, descriptive phase for identifying, defining, and documenting what is happening in the setting and relevant to the questions asked;

Thinking—after looking, it involves deeper exploration, reflection, interpretation, and analysis, resulting in some kind of potentially theoretical explanation for the situation; and

Acting—developing a plan for intervention, implementing it with community partners, and evaluating the outcomes of the actions in alliance with the participants.

To confront recognized disparities, my transition from practice to research evoked the voices and perspectives of rural residents directly. The dissertation study described and critically analyzed retired migrant workers’ definitions of health, as well as their personal experiences with the health care system. Returning to NM soon after that, I launched two critical ethnographic studies, based on CBPR, in rural counties near the international border with Mexico. All studies were approved by university institutional review boards, and all participants signed informed consent forms. My definition of rural came from the U.S. Census Bureau: “open country and settlements of less than 2,500 residents, exclusive of embedded suburbs of urbanized areas of 50,000 or more population” (Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2005, p. 19).

For the meta-ethnography, it was not feasible to retrace contacts with former informants across the years of the original studies and re-interview them. Additionally, the surrounding contexts for all of them have changed. However, knowing that their voices and perceptions informed and shaped the findings for the three studies made it reasonable to proceed with the meta-synthesis, exploring common threads, issues, and trends across the three qualitative studies (Fousekis, 2005; Noblit & Hare, 1988; Paterson et al., 2001; Patton, 2015).

Summarizing the Three Studies for the Meta-Ethnography

A synthesis of the three studies is shown in Table 1. Presentation of sample characteristics, study aims, and findings provides a context for the major focus of this article, which is the meta-synthesis. More detailed discussions of the individual studies and findings reside in available literature (Averill, 1997, 2002a, 2002b, 2002c, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2008, 2012). Inclusion criteria for the studies were that (1) each had been done by the author in a rural western U.S. setting, using critical ethnography and community partnership; (2) each involved older, rural, multicultural, community-dwelling adults; and (3) each represented an effort to better describe and analyze health disparities in a vulnerable group from their perspective and in their contexts. Sample size for a meta-synthesis is not driven by a statistical analysis, but instead is purposeful (e.g., examining larger patterns and trends across a body of research and settings familiar to the author and important to public health) and can be established by the researcher’s intent for such an investigation (Paterson et al., 2001; Patton, 2015).

TABLE 1.

Synthesis of the Three Studies

| Study and sample | Aims | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Study #1. Health Care Experiences of Elderly Rural Latinos (N = 43): 23 participants were community-dwelling older Hispanics, aged 60–94 y (primary participants); 20 were adult family members, care providers, and care managers (secondary participants), comprising Hispanic and White individuals, aged 20–50 y. Approximately 1/3 men and 2/3 women. | To explore the meaning of health, health care perceptions, and experiences of Hispanic older adults in rural communities of NE CO → critical ethnography (not CBPR). |

|

| Study #2. Health Care Perceptions of Rural Older Adults in Southwestern New Mexico: A Pilot Study (N = 22 adults): majority were aged 65+ y (primary participants); remainder adult caregivers, health care planners-providers-managers (secondary participants). Two groups represented in sample: retired miners-ranchers-loggers/spouses; recent retirees from other regions, generally with more education & resources. About 1/4 Hispanic, 3/4 White non-Hispanic; approximately 1/3 men, 2/3 women. | To explore the meaning of health, health care perceptions, and health care issues for multicultural, rural older adults in Grant County, NM (near SW border of NM–Mexico), from the participants’ perspectives. |

|

| Study #3. Health Care Perceptions and Issues for Rural Older Adults (N = 64 adults): majority 65+ y (primary participants); remainder adult caregivers, health care planners-providers-managers (secondary participants). Two groups represented in sample: retired miners-ranchers-loggers/spouses; recent retirees from other regions, generally with more education & resources. Approximately 1/3 Hispanic, 2/3 White, non-Hispanic; approximately 1/3 men, 2/3 women. | To explore the meaning of health, health care perceptions, and health care issues for multicultural, rural, older adults in Grant County, NM (near SW border of NM–Mexico), from the participants’ perspectives. |

|

Methods for meta-ethnography

Although each of the three studies applied CBPR by engaging participants in all phases of the research, the meta-ethnography involved (1) detailed review of each study, including research questions, methods, and findings; (2) peer debriefing with other qualitative researchers twice during the analysis, during a monthly seminar on qualitative methods; (3) identification and mapping of major concepts and themes for each study, then for the blended findings; (4) identification, analysis, and resolution of any contradictions and refutations across studies; and (5) creation of a general interpretation and synthesis across the set of studies, especially with applicability to practice and research in multicultural, rural settings. The methods are illustrated in Figure 1, demonstrating both substance and process. Key to this method was critical reflection or reflexivity at all phases of integration, synthesis, and interpretation. Patton (2015) said that “Reflexivity turns mindfulness inward … attentive to and conscious of the cultural, political, social, linguistic, and economic origins of one’s own voice and perspective, as well as the perspective and voices of those one interviews” (p. 70). This kind of reflexivity involved repeated re-emergence into the transcripts, field notes, and researcher’s reflective notes for each study. The intent of this deeper, secondary look at the original data helped generate an updated interpretation of essential findings, especially because the units of analysis here were the original studies-as-composite instead of simply a set of data for one study at a time. An essential element of qualitative research, critical reflection heightened my awareness of the subtle differences between or among findings, revealing the tacit, inner, phenomenal knowing of commonalities that became the semantic knowing I generated in writing about it (Lincoln, 2002; Polanyi, 1983). Specific criteria for evaluating meta-synthesis study rigor are dependent on the study purpose, the kinds of data being examined, and the contextual factors that may shape the process (Patton, 2015). However, in a general sense, study integrity was accomplished by use of transparent process, audit trails of all research actions, peer debriefing, adherence to ethical standards, congruence between the conceptual and methodological dimensions of the work, and critical reflection as defined earlier (Morse, 2012; Paterson et al., 2001).

Figure 1.

The methods used for all three studies

Results

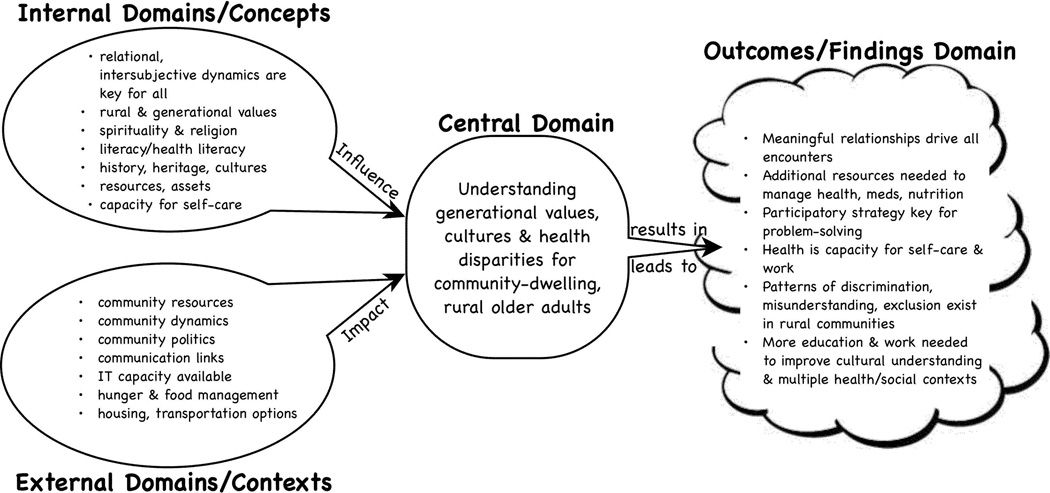

Consistent with the meta-ethnographic methods, results of this analysis appear in Figure 2, presented as a detailed concept map for the various domains of interest across the set of studies. Major cumulative concepts and ideas were recurrent, commonly shared points or ideas across all studies. They included interpersonal engagement, self-defined health, health disparities and inequities, access to care and prescriptions, and cultural humility. Overall themes were: (1) health is the capacity for self-care and work; (2) meaningful relationships with families and individuals are essential in health care; (3) cultural, economic, and ethnic patterns of discrimination and inequity persist in rural communities; (4) inadequate literacy and health literacy are barriers; and (5) food insecurity is a significant problem for many older adults. Paterson et al. (2001) suggested that an outcome of meta-analysis and synthesis is meta-theory. In this instance, Figure 2 represents a nascent attempt to visualize a potential model related to understanding older, rural, multicultural adults in their health-related contexts. More work remains to be done in refining and clarifying this early model and its propositional statements.

Figure 2.

Meta-findings from all three studies

Contextualizing the Findings in Current Literature and Data

Examining a meta-synthesis in the context of studies that may be similar takes place after the meta-analysis and meta-synthesis are complete (Patton, 2015). The six major outcomes/findings domains, or overarching themes, identified here are common across the literature on rural populations and groups. Unique to them, however, are the specific contexts of geography, ecology, cultural and ethnic groups, patterns of migration for particular occupations and economies, international border disputes, and current community resources working to resolve and redress the inequities. Ultimately, solutions or improvements may only come one community at a time, since the residents themselves are the experts in their own surroundings, collateral, and power. But my argument is that strategies at both the micro and macro levels are needed to be successful. Local health councils, volunteer groups, business groups, educators, and researchers may address some of the problems most effectively. For other challenges, a larger initiative is needed upstream for policies, allocation of major resources, and legislation to support human communities over other interests.

A review of multiple databases demonstrates support and consonance not only in the United States, but also abroad, for these major issues (see Table 2). For the respective domains, especially the synthesis outcomes or findings domain, similar conclusions have come from regional and national studies, supporting a call to action on behalf of some of our most vulnerable citizens.

TABLE 2.

Literature Synthesis

A CBPR Model

Analyzing the components, interactions, and associations among the identified domains, I found it useful to take a step back and try to visualize the total set of works and where/how they fit in the context of research literature and working models for how the scientific community conceptualizes and utilizes the complex, multilevel systems that characterize this content. One model that blends a CBPR approach with factors and issues similar to the ones presented here is from Wallerstein et al. (2008). Their Conceptual Logic Model of Community-Based Participatory Research: Process to Outcomes (p. 380) is a valuable heuristic device by which to see and describe the key components and characteristics that inform the previously described studies. Its capacity to capture a very similar set of key concepts and contexts, from identification through to intervention and potential outcomes, was congruent with the work presented here, and it also arose from multicultural social scientists working across CO’s and NM’s diverse cultural and ethnic populations.

National perspective

This synthesis emerged at a time when the new Affordable Care Act (https://www.healthcare.gov/) was being rolled out nationally, with many questions and unresolved components. In 2012, 64% of the nation’s population had private health insurance, 16% had Medicaid, 16% had Medicare, and 15% were uninsured; New Mexico ranked as the fourth worst state for uninsured residents in 2009–2012 and the second poorest state in the nation (U.S. Census Bureau, 2013). Also in 2012, persons over 65 years of age living in NM made up 14.1% of the total population (compared with 13.7% nationally). From 2009 to 2013, 20.4% of New Mexicans over the age of 65 lived below the federal poverty level, compared with 15.4% nationally (U.S. Census Bureau, 2015). Even the Healthy People 2020 initiative has called for major resources and efforts directed at managing symptoms of chronic disease, improving quality of life, and developing caregiver resources for older adults (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2015). Taken along with the other identified disparities in this study, as well as the national and local economic conditions, these facts decrease the likelihood that older rural adults can achieve access to the needed resources any time soon.

International perspective

Recognized as a significant public health challenge, the meta-synthesis findings resonate even internationally, as evidenced by the recent Executive Summary from the World Health Organization (WHO, 2008), calling for worldwide action on the social determinants of health to achieve health equity across the lifespan. Their three principles of recommended action included to “improve daily living conditions; tackle the inequitable distribution of power, money, and resources; measure and understand the problem and assess the impact of action” (p. 2).

Implications for Rural Research and Practice

This meta-synthesis adds understanding and depth to the health care perceptions, experiences, and disparities often encountered in isolated rural settings where multiple cultural groups reside, as explained by the people themselves. Often, these families involve more than one generation; the mingling of native, migratory, or transitional cultural groups near an international border; the potential clash of values and priorities for daily life; and patterns of marginalization from the mainstream population. The study strived to qualitatively document, describe, understand, and interpret the problems that older rural adults encounter as they age, become ill and frail, and manage their health care in poorly resourced communities. Implications of the findings hold dimensions of theory, research, practice, policy, and education.

Lee and McDonagh (2010) analyzed the history and theoretical development of rural nursing theory and made recommendations for the future of its advancement. Recognizing the seminal midrange theoretical work done by Long and Weinert (1989), they proposed that (1) rural residents’ definitions of health were evolving from a strictly functional role capacity to a more holistic view of body-mind-spirit; (2) rural values of hardiness and autonomy are intact but more receptive to help from outsiders than previously; (3) problems of maintaining anonymity and role definitions between residents and providers remain a challenge; and (4) the extent to which distance is a problem is equivocal across settings. They recommended changes to rural nursing theory that added the concepts of “health-seeking behaviors, choice, environmental context, and social capital” (Lee & McDonagh, 2010, p. 28).

For this meta-ethnography, there were points of convergence and divergence regarding Lee and McDonagh’s (2010) perspective. I propose that the reasons for this finding may arise from (1) the age of the sample population (all older adults, as opposed to residents across the lifespan); (2) the demographic composition of the sample in terms of ethnicity and possible marginalization from mainstream groups; and (3) the capacity of participants for health literacy, adequate food and housing, transportation, and participation in community activities.

Conceptually, as shown in Figure 2, internal domains of relational dynamics, resources, and heritage shaped the individual participants; external domains belonging to the situational features and communities tended to exclude many participants from having a full array of choices. Central to all of the internal domains was the need to better understand generational and cultural values in the context of a different, more dominant mainstream setting. Outcomes supported the need for meaningful relationships between older adults and their care providers; additional resources for basic access to food, medications, and transportation; participatory strategies for identifying and resolving problems; health as the ability to perform daily tasks and activities; persistent patterns of discrimination and bias against Hispanic residents; and a strong need for more extensive education on access and inclusion strategies for all groups.

In terms of theory, this work represents an attempt to both describe and partially explain the key concepts and propositions that exist in a population of older rural adults in the southwestern United States. It serves as an example of how applying a CBPR model such as Stringer’s Look-Think-Act can yield important insights into theory development for groups not dominated by the mainstream societal perspective. Given the level of health disparities in this group, a need exists to further develop not only the theoretical base but also the clinical interventions for eliminating patterns of inequity in health care. The National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD, n.d.) notes, “While the diversity of the American population is one of the nation’s greatest assets, one of its greatest challenges is reducing the profound disparity in health status of its racial and ethnic minority, rural, low-income, and other underserved populations” (Inside NIMHD section, para. 1).

Based on the findings of this meta-synthesis and other related studies, several major implications for rural research and practice can be drawn. First, successful efforts to address and resolve rural health disparities must engage the voices of community residents and advisers from all key stakeholder groups, planners, researchers, and organizations. Regionally, nationally, and internationally, strategies of engagement and collaboration are recommended by researchers, policy makers, and public health advocates to reduce disparities and eliminate health-related inequities (Borders, 2004; Holmes & Joseph, 2011; Kotelchuck, Lowenstein, & Tobin, 2011; Weinhold & Gurtner, 2014; WHO, 2008). This recommendation applies to public health nurses (PHNs) in practice, as well as to rural health researchers. Consistent with the findings of Shreffler-Grant and Reimer (2010) in both the United States and Canada, practice and health service goals for PHNs and others should incorporate the local perspective, priorities, cultural beliefs, and customs of groups like the ones represented in this meta-ethnography.

In addition, a need exists in rural areas for advanced practice nurses (APRNs) who understand rural and community norms and can effectively address the crises that often result when residents wait until they are seriously ill or injured before seeking professional care (Hauenstein et al., 2014). Data show that, in general, both nationally and internationally, the shortage of adequate heath care in rural settings is a function of multiple factors, including provider shortages, deficient quality of the care available, work overload for existing health care professionals, and the feasibility of longstanding, trusted relationships between residents and providers, including nurses (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2015; Weinhold & Gurtner, 2014).

One example of this rural outreach involving APRNs has just begun at the University of New Mexico through the established program known as Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes; 2015b). Project ECHO was established in 2003 as a medical/physician outreach program utilizing weekly virtual clinics online. A mechanism for sharing primary and specialty care knowledge and expertise in underserved rural parts of NM, Project ECHO recently included family nurse practitioners and certified nurse midwives into the outreach work. The APRNs are now developing their own Project ECHO (2015a) initiative. These findings suggest a need to develop more resources (educational, assistive, and collaborative) for PHNs, who often bridge the gap between seriously ill people who are discharged to uncertain situations at home and healthy but chronically ill older adults who desire to remain at home throughout late life.

To develop and sustain these needed resources for PHNs, consideration must be given to the policy implications attached to implementation. Weinhold and Gurtner (2014) summarized the major dimensions of inadequate rural health care as infrastructural, professional, educational, sociocultural, economical, and political. They argued that critical analysis of these factors should inform policy makers who allocate resources, make decisions about services provided, and influence health care outcomes for poor, elderly, and marginalized groups in rural settings. Because rural communities like the ones of interest to this study often are economically challenged to meet basic health care needs across settings, including access to adequate food, transportation, and primary/preventive care, practice and policy interventions should integrate with existing work, culture, and role performance for multicultural rural adults (Russell, 2005; Shreffler-Grant & Reimer, 2010).

Additionally, work is needed to extend education, acceptance, and understanding regarding multiple cultures, ethnic groups, age groups, customs, and rural contexts to nurses and others who practice in rural settings. Based not only on this meta-synthesis but also on related literature, patterns of misunderstanding, discrimination, harming, and exclusion persist in many rural communities. Important efforts to address these educational disparities are under way, but additional contributions from the varied voices of multicultural rural communities remain to be fully developed.

Molinari and Bushy (2012) created a text authored by rural health experts dedicated to providing “conceptual and practical information that can be used by nurses and leaders in rural settings to develop, implement, and evaluate innovative programs designed to meet local needs and preferences” (p. xxi). Shreffler-Grant and Reimer (2010) called for nursing education to incorporate rural residents’ definitions and views of health into their practice. Hauenstein et al. (2014) formalized an educational model known as Transformational Nursing Leadership in Rural Health Care to integrate rural health content into the APRN curriculum at the University of Virginia. Their program emphasizes leveraging specific knowledge of rural communities and population groups, led by nurses “in interaction with rural residents and their communities to improve the effectiveness of the rural health care system and health outcomes for rural residents” (Hauenstein et al., 2014, p. 466).

Conclusions

It is clear that participatory and collaborative strategies will be needed to identify, prioritize, implement, and evaluate the effectiveness and fit of interventions for practice, policy, education, or research. The findings of this meta-ethnography provide support for the recommendations of the Rural Nurse Organization (2015) and IOM’s (2011) document, The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health, both of which recommend that nurses practice to the full extent of their training and capacity; receive education that will prepare them for a richly diverse world of individuals, families, and groups; accept opportunities for leadership, partnerships, and shared efforts across disciplines and settings; and for nurse researchers, contribute their skills and knowledge to the generation of data and evidence in all care settings and organizations. With our modern technological capacity, communications networks, emphasis on interprofessional collaboration, and mobility of our populations, the time is right to actualize the changes needed for health equity and health care access for rural families. To do less is to undermine the values of a humane, compassionate, and equitable system of care for an aging and underserved population that is expanding in our rural communities.

Acknowledgments

Support from NIH/NINR F31NR07037 (National Research Service Award), The University of New Mexico College of Nursing Dean’s Research Fund (2001), Consortium Agreement #UTA02-020 between the University of Texas at Austin School of Nursing and the University of New Mexico College of Nursing: NIH/NINR 1-P30-NR05051 (CFDA#93.361), 1R15NR008217-01A2, 2005-2008 (NIH).

References

- American Public Health Association, Public Health Nursing Section. [Retrieved July 27, 2015];The definition and practice of public health nursing: A statement of the APHA Public Health Nursing Section: 2013. 2013 Nov 11; from http://apha.org/~/media/files/pdf/membergroups/nursingdefinition.ashx. [Google Scholar]

- Averill JB. Health care experiences of elderly rural Latinos. Denver: The University of Colorado; 1997. (unpublished doctoral dissertation) [Google Scholar]

- Averill JB. A portrait: Magdalena's dream. Public Health Nursing. 2002a;19(3):156–160. doi: 10.1046/j.0737-1209.2002.19302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averill JB. Matrix analysis as a complementary analytic strategy in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Health Research. 2002b;12(6):855–866. doi: 10.1177/104973230201200611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averill JB. Voices from the Gila: Health care issues for rural elders in southwestern New Mexico. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2002c;40(6):1–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averill JB. Keys to the puzzle: Recognizing strengths in a rural community. Public Health Nursing. 2003;20(6):449–455. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2003.20605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averill JB. Merging critical ethnography with community–based action research in studies of rural elders. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2005;30(12):11–18. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20051201-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averill JB. Getting started: Initiating critical ethnography and community-based action research in a program of rural health studies. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2006;5(2) doi: 10.1177/160940690600500206. Retrieved from http://www.ualberta.ca/~ijqm/backissues/pdf/5_2/averill. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averill JB. Appendix F: Community partnership through a nursing lens. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008. pp. 431–433. [Google Scholar]

- Averill JB. Priorities for action in a rural older adults study. Family & Community Health. 2012;35(4):358–372. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e318266686e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bales RL, Winters CA, Lee HJ. Health needs and perceptions of rural persons. In: Winters CA, Lee HJ, editors. Rural nursing: Concepts, theory, and practice. New York, NY: Springer; 2010. pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Bocker E, Glasser M, Nielsen K, Weidenbacher-Hoper V. Rural older adults’ mental health: Status and challenges in care delivery. Rural and Remote Health. 2012;12:2199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borders TF. Rural community-dwelling elders’ reports of access to care: Are there Hispanic versus non-Hispanic white disparities? Journal of Rural Health. 2004;20(3):210–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2004.tb00031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark PG, Blissmer BJ, Greene GW, Lees FD, Riebe DA, Stamm KE. Maintaining exercise and healthful eating in older adults: The SENIOR project II: Study design and methodology. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2011;32(1):129–139. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fousekis NM. Experiencing history: A journey from oral history to performance. In: Pollock D, editor. Remembering: Oral history performance. New York, NY: Palgrave MacMillan; 2005. pp. 167–186. [Google Scholar]

- Gadamer HG. Truth and method. 2nd rev. ed. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz C. The interpretation of cultures. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Greaves CJ, Farbus L. Effects of creative and social activity on the health and well-being of socially isolated older people: Outcomes from a multi-method observational study. The Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health. 2006;126(3):134–142. doi: 10.1177/1466424006064303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo G, Phillips L. Key informants’ perceptions of health care for elders at the US-Mexico border. Public Health Nursing. 2006;23(3):224–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2006.230304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauenstein EJ, Glick DF, Kane C, Kulbock P, Barbero E, Cox K. A model to develop nurse leaders for rural practice. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2014;30(6):463–473. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes WR, Joseph J. Social participation and healthy ageing: A neglected, significant protective factor for chronic non communicable conditions. Global Health. 2011;7(43):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-7-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz CR, Robinson M, Seifer S. Community-based participatory research from the margin to the mainstream: Are researchers prepared? Circulation. 2009;119(19):2633–2642. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.729863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton S, Johnson R. Improving access to health care for uninsured elderly patients. Public Health Nursing. 2010;27(4):362–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2010.00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Quality through collaboration: The future of rural health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotelchuck R, Lowenstein D, Tobin JN. At the intersection of health, health care and policy. Health Affairs. 2011;30(11):2090–2097. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, McDonagh MK. Updating the rural nursing theory base. In: Winters CA, Lee HL, editors. Rural nursing: Concepts, theory, and practice. New York, NY: Springer; 2010. pp. 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS. Emerging criteria for quality in qualitative and interpretive research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. The qualitative inquiry reader. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. pp. 327–345. [Google Scholar]

- Long KA, Weinert C. Rural nursing: Developing the theory base. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice: An International Journal. 1989;3(2):113–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longman JM, Rolfe MI, Passey MD, Heathcote KE, Ewald DP, Dunn T, Morgan GG. Frequent hospital admission of older people with chronic disease: A cross-sectional survey with telephone follow-up and data linkage. BMC Health Services Research. 2012;12:373. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallers MH, Claver M, Lares LA. Perceived control in the lives of older adults: The influence of Langer and Rodin’s work on gerontological theory, policy, and practice. The Gerontologist. 2013;54(1):67–74. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton SA, Crawford D, Ball K, Salmon J. Understanding determinants of nutrition, physical activity and quality of life among older adults: The Wellbeing, Eating and Exercise for a Long Life (WELL) study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2012;10:109. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Introduction to community-based participatory research. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008. pp. 5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Molinari DL, Bushy A, editors. The rural nurse: Transition to practice. New York, NY: Springer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM. Qualitative health research. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- National Conference of State Legislatures. Meeting the primary care needs of rural America: Examining the role of non-physician providers; 2015. [Retrieved July 27, 2015]. from http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/meeting-the-primary-care-needs-of-rural-america.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. [Retrieved July 27, 2015];Inside NIMHD. (n.d.). from http://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about.html.

- Noblit GW, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. [Retrieved July 27, 2015];Older adults. 2015 Jun 1; from http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/older-adults?topicid=31.

- Paterson BL, Thorne SE, Canam C, Jillings C. Meta-study of qualitative health research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods. 4th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Polanyi M. The tacit dimension. Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Project ECHO. [Retrieved July 27, 2015];Model. 2015a from http://echo.unm.edu/about-echo/model/ [Google Scholar]

- Project ECHO. [Retrieved July 27, 2015];Our story. 2015b from echo.unm.edu/about-echo/our-story/ [Google Scholar]

- Rural Nurse Organization. [Retrieved July 27, 2015];Our resolutions. 2015 from http://www.rno.org/page-3/something-1/ [Google Scholar]

- Russell SA. Hunger: An unnatural history. New York, NY: Basic Books; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schoen C, Osborn R, Squires D, Doty MM. Access, affordability, and insurance complexity are often worse in the United States compared to ten other countries. Health Affairs. 2013;32(12):2205–2215. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shreffler-Grant J, Reimer MA. Implications for education, practice, and policy. In: Winters CA, Lee HL, editors. Rural nursing: Concepts, theory, and practice. New York, NY: Springer; 2010. pp. 437–445. [Google Scholar]

- Stanhope M, Lancaster J. Foundations of nursing in the community: Community-oriented practice. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby-Elsevier; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stringer ET. Action research. 4th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Trickett EJ, Beehler S. The ecology of multilevel interventions to reduce social inequalities in health. American Behavioral Scientist. 2013;57(8):1227–1246. [Google Scholar]

- Truglio-Londrigan M, Lewenson SB. Public health nursing: Practicing population-based care. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. [Retrieved June 30, 2013];State & county quickfacts. New Mexico. 2013 from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/35000.html.

- U.S. Census Bureau. [Retrieved July 27, 2015];State and county quickfacts. New Mexico. 2015 from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/35000.html.

- Wallerstein N, Oetzel J, Duran B, Tafoya G, Belone L, Rae R. What predicts outcomes in community-based participatory research? In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008. pp. 371–392. [Google Scholar]

- Weinhold I, Gurtner S. Understanding shortages of sufficient health care in rural areas. Health Policy. 2014;118(2):201–214. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinert C, Cudney S, Kinion E. Development of My Health Companion to enhance self-care management of chronic health conditions in rural dwellers. Public Health Nursing. 2010;27(3):263–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2010.00852.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiles JL, Wild K, Kerse N, Allen RES. Resilience from the point of view of older people: ‘There’s still life beyond a funny knee.’. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;74(3):416–424. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters CA, Sullivan T. The chronic illness experience of isolated rural women: Use of an online support group intervention. In: Winters CA, Lee HL, editors. Rural nursing: Concepts, theory, and practice. New York, NY: Springer; 2010. pp. 179–192. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final Report-Executive Summary. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wright DB. Care in the country: A historical case study of long-term sustainability in 4 rural health centers. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(9):1612–1618. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.146050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]