Abstract

Alzheimer's disease (AD) represents the most frequent progressive neuropsychiatric disorder worldwide leading to dementia. We systematically investigated the presence and extent of the AD‐related cytoskeletal pathology in serial thick tissue sections through all subcortical brain nuclei that send efferent projections to the transentorhinal and entorhinal regions in three individuals with Braak and Braak AD stage 0 cortical cytoskeletal pathology and fourteen individuals with Braak and Braak AD stage I cortical cytoskeletal pathology by means of immunostainings with the anti‐tau antibody AT8. These investigations revealed consistent AT8 immunoreactive tau cytoskeletal pathology in a subset of these subcortical nuclei in the Braak and Braak AD stage 0 individuals and in all of these subcortical nuclei in the Braak and Braak AD stage I individuals. The widespread affection of the subcortical nuclei in Braak and Braak AD stage I shows that the extent of the early subcortical tau cytoskeletal pathology has been considerably underestimated previously. In addition, our novel findings support the concept that subcortical nuclei become already affected during an early ‘pre‐cortical’ evolutional phase before the first AD‐related cytoskeletal changes occur in the mediobasal temporal lobe (i.e. allocortical transentorhinal and entorhinal regions). The very early involved subcortical brain regions may represent the origin of the AD‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology, from where the neuronal cytoskeletal pathology takes an ascending course toward the secondarily affected allocortex and spreads transneuronally along anatomical pathways in predictable sequences.

Keywords: allocortex, Alzheimer's disease, cytoskeletal pathology, entorhinal region, prion‐like diseases, subcortical nuclei, tau protein

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressive neuropsychiatric disorder and represents the most frequent dementing disorder accounting for 60%–70% of demented individuals 11, 18, 38, 47, 51, 52, 71, 74, 89. Because of its estimated frequency of approximately 25 million patients worldwide in 2001 and the occurrence of approximately 5 million new AD cases per year, AD is a tremendous burden not only for diseased individuals, their families and caregivers, but also for health systems and social economies 8, 11, 18, 38, 47, 52, 58, 71.

The neuropathology of AD is characterized by neuronal loss at specific cortical and subcortical brain sites (ie, transentorhinal and entorhinal regions, hippocampus, amygdala, medial septal nucleus, nuclei of the diagonal band of Broca, basal nucleus of Meynert, compact part of the substantia nigra, locus coeruleus, midbrain and pontine raphe nuclei), as well as intraneuronal and extraneuronal deposits of abnormal proteins 13, 14, 15, 18, 25, 28, 29, 33, 35, 43, 47, 52, 93. The extraneuronal deposits are formed by the insoluble β‐amyloid protein and the intraneuronal deposits by the abnormally phosphorylated tau protein 4, 5, 8, 11, 13, 14, 15, 18, 23, 27, 29, 33, 35, 38, 46, 48, 49, 52, 58, 59, 74, 92, 93, 96.

Tau, an axonal cytoskeletal and the major microtubule associated protein (MAP), becomes hyperphosphorylated in nerve cells of AD brains due to an imbalance of multiple protein kinases and phosphatases. In the disease state hyperphosphorylation of tau leads to: (i) a reduced affinity for microtubules and ineffective microtubule polymerization, assembly and stabilization; (ii) loss of microtubule rails and impairments of intra‐axonal transport mechanisms; and (iii) to tau insolubility, its self‐aggregation and deposition in affected neurons 5, 8, 11, 12, 18, 23, 26, 27, 29, 32, 37, 38, 47, 48, 49, 58, 59, 62, 71, 74, 79, 89, 91, 92, 96.

Neuronal aggregations of the tau protein acquire the form of paired helical filaments (PHF) which represent the ultrastructural basis of the AD‐related cytoskeletal pathology and coalesce into neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) in neuronal perikarya and into dendritic neuropil threads (NT) originally described by Alois Alzheimer and Oskar Fischer 4, 5, 6, 8, 11, 12, 13, 14, 18, 22, 23, 29, 32, 35, 37, 38, 39, 47, 48, 49, 52, 58, 59, 62, 65, 74, 89, 96. The stereotypical, gradual and hierarchical recruitment of regions of the cerebral cortex by the AD‐related hyperphosphorylated tau cytoskeletal pathology has allowed to establish a staging procedure that describes its increasing severity, distribution and topographical spread (ie, Braak and Braak AD stages in the evolution of the AD‐related cortical cytoskeletal pathology). The predictable temporal and spatial sequences of the expansion of the AD‐related cortical tau cytoskeletal pathology start from the transentorhinal region of the mediobasal temporal lobe, reach out to the immediately adjacent entorhinal region, extend into the hippocampus and ultimately affect all portions of the cerebral neocortex. This reproducible and fairly stereotypic progression also implies a long‐lasting preclinical phase of approximately three to four decades during which every day relevant cognitive deficits are not yet evident 4, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 27, 29, 30, 32, 35, 44, 52, 58, 59, 65, 68.

Because of the early appearance of tau cytoskeletal pathology in neurons of the transentorhinal and entorhinal regions, it has been believed for a long time that the cerebral allocortex represents the first brain target of the AD‐related cytoskeletal pathology 9, 10, 12, 14, 16, 17, 18, 32, 33, 35, 39, 55, 71, 78, 89, 96. However, several studies suggested that the AD‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology also occurs rather early in specific nuclei of the basal forebrain, thalamus and brainstem, all of which are anatomically connected with the allocortical transentorhinal and entorhinal regions via fiber tracts and were not included in the original Braak and Braak AD staging scheme 13, 14, 29, 30, 39, 40, 67, 71, 73, 80, 82, 83, 84, 88, 89. Although the original staging system has been recently extended, our preliminary findings of pilot studies indicated that the very early subcortical tau pathology may be more widespread than described in the revised Braak and Braak AD staging system and in addition to the locus coeruleus may also affect a large variety of other subcortical nuclei with projections to the early affected entorhinal and transentorhinal regions 13, 14, 18, 21.

It is well known that all of the subcortical nuclei with efferent projections to the allocortical transentorhinal and entorhinal regions consistently exhibit a marked neuronal tau pathology in demented AD patients burdened by Braak and Braak AD stage V or VI tau cytoskeletal pathologies 2, 3, 15, 18, 29, 33, 40, 56, 57, 67, 72, 73, 82, 83, 84, 86, 88 (Supporting Information Figures S1–S5). Considering our preliminary findings, we therefore hypothesized that the high vulnerability of the subcortical sites with efferent projections to the transentorhinal and entorhinal regions for the AD‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology is not only mirrored by their marked and consistent involvement in the late Braak and Braak AD stages V and VI, but may also be reflected by their very early involvement during the evolution of the AD‐related tau pathology. Accordingly, we tested the hypothesis by investigating the presence and extent of the AD‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology in all subcortical nuclei sending efferent projections to the transentorhinal and entorhinal regions 45, 61 in individuals with Braak and Braak AD stage I or 0 cortical tau cytoskeletal pathology (Supporting Information Figures S1–S5).

Patients and Methods

A total of 44 brains from patients without neurological or psychiatric diseases in their medical histories and intact cognitive functions upon clinical examination (22 females, 22 males, age at death: 54.20 ± 17.70 years) submitted to autopsy at the Department of Pathology and Medical Biology at the University Medical Center Groningen, the Netherlands, were screened for this study. The brains of all 44 individuals were examined macroscopically, fixed in 4% non‐buffered formaldehyde, investigated for purposes of neuropathological diagnosis by an experienced neuropathologist (W den D) and eventually classified using the Braak and Braak AD staging procedure distinguishing stages I–VI in the distribution and severity of the AD‐related cortical tau cytoskeletal pathology 4, 10, 13, 14, 16, 18, 27, 29, 30, 32, 35, 44, 65. This neuropathological classification revealed the presence of three brains with Braak and Braak AD stage 0 (1 female, 2 males; age at death: 29.0 ± 11.36 years) and 14 with Braak and Braak AD stage I (6 females, 8 males; age at death: 43.4 ± 12.00 years) cortical cytoskeletal pathology among the screened 44 control brains (Supporting Information Table S1). Autopsies were performed in these Braak and Braak AD stage 0 and I individuals within 13.94 ± 9.9 h post‐mortem (Supporting Information Table S1).

For comparison and additional demonstration of their exceptionally high vulnerability, we also documented the AD‐related cytoskeletal pathology in the subcortical nuclei sending efferent projections to the transentorhinal and entorhinal regions 45, 61 of seven patients in Braak and Braak AD stage V or VI (two females, five males; age at death: 74.0 ± 5.48 years) 13, 14, 18 which were clinically diagnosed as demented or suffered from incipient dementia (Supporting Information Table S2).

Tissue processing

For purposes of neuropathological classification of their AD‐related cortical cytoskeletal pathology according to the Braak and Braak AD staging system, at least six tissue sections through recommended brain regions of all 44 control individuals were treated with the monoclonal antibody AT8 to visualize the hyperphosphorylated cytoskeletal protein tau (1:2000; Thermo Scientific Pierce Products, Rockford, IL, USA) 12, 13, 14, 18, 29, 39, 44, 65, 83. The AT8 antibody recognizes phosphorylated tau epitopes at serine 202 and threonine 205 and reveals a robust and reliable immunoreactivity for hyperphosphorylated tau protein in human brain autopsy material regardless of the length of the fixation time in formaldehyde and/or the condition of the preserved tissue 12, 13, 29, 39. The specificity of the immunostaining was analyzed by omission of the primary antibody. Incubation of free‐floating sections with the AT8 antibody was carried out for 40 h at 4°C. Incubation with the second biotinylated antibody (anti‐mouse IgG) was performed for 2 h. Immunoreactions were visualized by means of the AB complex (Vectastain, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and 3,3‐diaminobenzidine‐tetra‐HCl/H2O2 (DAB D5637, Sigma, Taufkirchen, Germany).

Subsequent to the neuropathological classification of their AD‐related cortical cytoskeletal pathology tissue blocks from the right cerebral hemispheres and the rostral brainstem of all Braak and Braak AD stage 0 and I individuals including the basal forebrain, mediobasal temporal lobe (with the amygdala, hippocampus, transentorhinal and entorhinal regions), claustrum, hypothalamus, thalamus, midbrain and pons were embedded in polyethylene glycol (PEG 1000, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) 14, 15, 20, 90 and cut into five equidistant series of 100‐μm‐thick tissue sections (cerebral blocks: frontal sections; brainstem blocks: horizontal sections). All tissue staining was performed on free‐floating sections. In each individual, every fifth of the 100‐μm‐thick serial sections were stained for lipofuscin pigment with aldehyde fuchsin and for Nissl material with Darrow red and used for anatomical orientation 20. Parallel sections were stained with the anti‐tau antibody AT8 (1:2000) 12, 13, 14, 18, 29, 39, 44, 65.

For purposes of pathoanatomical examination of their subcortical tau cytoskeletal pathology, at least five tissue sections through the following subcortical brain sites of all Braak and Braak AD stage 0 and I individuals were investigated: medial septal nucleus, nuclei of the vertical and horizontal limbs of the diagonal band of Broca, basal nucleus of Meynert, amygdala, claustrum, hypothalamus, thalamus, peripeduncular nucleus, dopaminergic substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area, periaqueductal gray, dorsal raphe nuclei, locus coeruleus, and parabrachial nuclei. The presence of the AT8‐immunoreactive tau pathology in the perikarya, perikarya and processes or only in the processes of nerve cells of these subcortical brain sites and their subnuclei (amygdala: cortical, accessory basal, lateral, and laterobasal nuclei, cortical transitional area; hypothalamus: dorsomedial, ventromedial, tuberomammillary and supramammillary nuclei, perifornical region and lateral area; thalamus: central medial, paraventricular, laterodorsal, subparafascicular, and central lateral nuclei, medial pulvinar and limitans–suprageniculate complex; dorsal raphe nuclei: supratrochlear and caudal compact parts) (Supporting Information Figures S1–S5) of the Braak and Braak AD stage 0 and I individuals was semiquantitatively assessed by UR and categorized into: AT8‐immunoreactive perikarya and/or processes of nerve cells not detectable even after a time period of 4 minutes of careful investigation of a given brain nucleus and application of 100× magnification (−), only scarce numbers of AT8‐immunoreactive perikarya and/or processes of nerve cells and only detectable after very careful examination and application of 100× magnification (+), a number of AT8‐immunoreactive perikarya and/or processes of nerve cells and quickly detectable light microscopically at 250× magnification (++) (Tables 1 and 2). Inter‐rater agreement between UR and KS regarding the detection of AT8‐immunoreactive nerve cell perikarya or processes was assessed by means of the weighted kappa coefficient Κw (BiAS for Windows, version 9.14, Epsilon, Darmstadt, Germany).

Table 1.

Distribution and extent of the AT8‐immunoreactive Alzheimer's disease (AD)‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology in nuclei of the basal forebrain, amygdala and hypothalamus with efferent projections to the transentorhinal and entorhinal regions in individuals with Braak and Braak stage I or 0. Abbreviations: AD = Alzheimer's disease; AM‐AB = accessory basal nucleus of the amygdala; AM‐C = cortical nucleus of the amygdala; AM‐CT = cortical transitional area of the amygdala; AM‐L = lateral nucleus of the amygdala; AM‐LB = laterobasal nucleus of the amygdala; CL = claustrum; DBH = nucleus of the horizontal limb of the vertical band of Broca; DBV = nucleus of the vertical limb of the diagonal band of Broca; HY‐DM = hypothalamic dorsomedial nucleus; HY‐L = hypothalamic lateral area; HY‐PF = hypothalamic perifornical region; HY‐SM = hypothalamic supramammillary nuclei; HY‐TM = hypothalamic tuberomammillary nucleus; HY‐VM = hypothalamic ventromedial nucleus; ME = basal nucleus of Meynert; MS = medial septal nucleus; N = nerve cell process; P = nerve cell perikaryon

| Case | AT8 | MS | DBV | DBH | ME | CL | AM‐CT | AM‐C | AM‐L | AM‐LB | AM‐AB | HY‐DM | HY‐VM | HY‐TM | HY‐PF | HY‐L | HY‐SM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P | ||||||||||||||||

| N | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| PN | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| 2 | P | ||||||||||||||||

| N | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| PN | + | + | + | ++ | + | ||||||||||||

| 3 | P | ||||||||||||||||

| N | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| PN | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| 4 | P | ||||||||||||||||

| N | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| PN | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | |||||||

| 5 | P | + | |||||||||||||||

| N | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| PN | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| 6 | P | ||||||||||||||||

| N | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| PN | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| 7 | P | ||||||||||||||||

| N | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| PN | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| 8 | P | ||||||||||||||||

| N | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| PN | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| 9 | P | ||||||||||||||||

| N | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||

| PN | + | + | + | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | ||||

| 10 | P | ||||||||||||||||

| N | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| PN | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| 11 | P | ||||||||||||||||

| N | + | ||||||||||||||||

| PN | + | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | + | ++ | + | ||

| 12 | P | ||||||||||||||||

| N | + | ||||||||||||||||

| PN | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| 13 | P | ||||||||||||||||

| N | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||

| PN | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | + | + | ++ | ||||

| 14 | P | ||||||||||||||||

| N | |||||||||||||||||

| PN | + | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| 15 | P | ||||||||||||||||

| N | + | + | + | + | ++ | ||||||||||||

| PN | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| 16 | P | ||||||||||||||||

| N | + | ||||||||||||||||

| PN | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | ||

| 17 | P | ||||||||||||||||

| N | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||

| PN | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

AT8‐immunoreactive cytoskeletal pathology in the perikarya (P), perikarya and processes (PN), or processes (N) of affected nerve cells.

Table 2.

Distribution and extent of the AT8‐immunoreactive Alzheimer's disease (AD)‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology in nuclei of the thalamus and brainstem with efferent projections to the transentorhinal and entorhinal regions in individuals with Braak and Braak stage I or 0. Abbreviations: AD = Alzheimer's disease; CEL = thalamic central lateral nucleus; CEM = thalamic central medial nucleus; DR‐CC = dorsal raphe nucleus, compact caudal part; DR‐ST = dorsal raphe nucleus, supratrochlear part; LC = locus coeruleus; LD = thalamic laterodorsal nucleus; LI = thalamic limitans–suprageniculate complex; MPB = medial parabrachial nucleus; N = nerve cell process; P = nerve cell perikaryon; PAG = periaqueductal gray; PP = peripeduncular nucleus; PU = thalamic pulvinar (medial subnucleus); PV = thalamic paraventricular nuclei; SN = substantia nigra, compact part; SPF = thalamic subparafascicular nucleus; VTA = ventral tegmental area

| Case | AT8 | CEM | PV | LD | SPF | CEL | PU | LI | PP | SN | VTA | PAG | DR‐ST | LC | DR‐CC | MPB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P | |||||||||||||||

| N | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | |||

| PN | ++ | ++ | ||||||||||||||

| 2 | P | |||||||||||||||

| N | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| PN | + | ++ | ||||||||||||||

| 3 | P | |||||||||||||||

| N | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| PN | + | + | ++ | |||||||||||||

| 4 | P | |||||||||||||||

| N | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| PN | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| 5 | P | |||||||||||||||

| N | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| PN | ++ | + | + | |||||||||||||

| 6 | P | |||||||||||||||

| N | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| PN | + | + | ||||||||||||||

| 7 | P | |||||||||||||||

| N | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | ||||

| PN | ++ | ++ | ++ | |||||||||||||

| 8 | P | |||||||||||||||

| N | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| PN | ||||||||||||||||

| 9 | P | |||||||||||||||

| N | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| PN | ++ | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | ++ | + | |||||||

| 10 | P | |||||||||||||||

| N | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| PN | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| 11 | P | |||||||||||||||

| N | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | ||||

| PN | + | ++ | ++ | |||||||||||||

| 12 | P | |||||||||||||||

| N | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | |||||||||||

| PN | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ||||||

| 13 | P | |||||||||||||||

| N | + | ++ | + | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| PN | + | + | + | ++ | ||||||||||||

| 14 | P | |||||||||||||||

| N | ||||||||||||||||

| PN | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| 15 | P | |||||||||||||||

| N | + | + | ||||||||||||||

| PN | ++ | + | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| 16 | P | + | ||||||||||||||

| N | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | ++ | |||||||||

| PN | ++ | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | |||||||||

| 17 | P | |||||||||||||||

| N | ++ | + | + | + | + | ++ | ||||||||||

| PN | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | ++ |

AT8‐immunoreactive cytoskeletal pathology in the perikarya (P), perikarya and processes (PN), or processes (N) of affected nerve cells.

Routine neuropathological investigation of the brains of the Braak and Braak stage V or VI individuals was performed by W den Dunnen and included assessment of their AD‐related cortical tau cytoskeletal pathology on recommended thin tissue sections according to the Braak and Braak AD staging procedure 13, 14, 18 (Supporting Information Table S2). For the pathoanatomical demonstration of the advanced subcortical tau cytoskeletal pathology, selected tissue blocks from the right cerebral hemisphere and the rostral brainstem of these Braak and Braak AD stage V or VI individuals were embedded in polyethylene glycol (PEG 1000) 14, 15, 20, 90 and cut into five equidistant series of 100‐μm‐thick tissue sections (cerebral blocks: frontal sections; brainstem blocks: horizontal sections). The first, fifth, tenth, etc. of the 100‐μm‐thick free‐floating cerebral and brainstem serial tissue sections were immunostained with the AT8 anti‐tau antibody (1:2000) 12, 13, 14, 18, 27, 29, 39, 44, 65, 83.

In all of our Braak and Braak AD stage 0, I, V and VI individuals select thin tissue sections through recommended brain sites were either immunostained with a monocloncal anti‐Aß antibody (1:400; DAKO, Heverlee, Belgium) to visualize ß‐amyloid deposits 93 or with a monoclonal antibody against alpha‐synuclein (1:40; Novocastra, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK) for the detection of Parkinson's disease (PD)‐related Lewy bodies (LB) and/or Lewy neurites (LN) 19. Furthermore, thin tissue sections through well‐known brain predilection sites (ie, amygdala and cortex of the medial temporal lobe) were also immunolabeled with a polyclonal antibody against the pathological form of the predominantly nuclear protein TDP‐43 (1:6400; Bioconnect, Huissen, the Netherlands) to demonstrate the presence of abnormal aggregations of TDP‐43 in nerve or glial cells 97. Neuropathological classification of the AD‐related ß‐amyloidosis was performed on the immunostained tissue sections according to the acknowledged Thal staging system that distinguishes five phases in the evolution of the AD‐related ß‐amyloidosis 93. The tissue sections immunostained for alpha‐synuclein were used to classify the PD‐related neuronal aggregation pathology according to the internationally accepted Braak et al PD staging procedure 19.

The AD‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology 18 and ß‐amyloidosis 77, as well as the PD‐related brain pathology 19, commonly affect the diseased brains bilateral symmetrically. In view of the bilateral symmetrical brain distribution of the AD‐ and PD‐related pathologies, we performed all of our neuropathological classifications and pathoanatomical studies of the subcortical l tau cytoskeletal pathology on brain tissue from one cerebral hemisphere (ie, right cerebral hemisphere) of our Braak and Braak AD stage 0, I, V and VI individuals.

Genomic DNA was extracted from formaldehyde‐fixed and paraffin‐embedded brain tissues to determine APOE genotypes of all Braak and Braak AD stage 0, I, V and VI individuals according to the method described previously 34. The frequencies of the APOE alleles (ε2, ε3 and ε4) were obtained by counting the alleles from the observed genotypes (Supporting Information Tables S1 and S2).

Brain tissue used for our pathoanatomical investigation of the subcortical tau cytoskeletal pathology was processed by M Bouzrou and APOE genotyping was performed by E Ghebremedhin. D Del Turco and K Seidel produced the figures of the AT8 immunostained tissue sections. H Heinsen, HW Korf, L Grinberg, J Bohl and S Wharton were involved in our initial pilot studies and in the design of our pathoanatomical investigations. In addition, they provided ongoing intellectual neuroanatomical and neuropathological support of our study and were significantly involved in the preparation of our manuscript.

The study was approved by the Ethical board of the Faculty of Medicine at the Goethe University of Frankfurt/Main.

Results

APOE genotypes

The distribution of the APOE genotypes in our Braak and Braak AD stage 0 and I individuals and in our Braak and Braak AD stage V and VI individuals is depicted in Supporting Information Tables S1 and S2. Briefly, the distribution of the allele frequencies of APOE ε2, ε3 and ε4 was 0.071, 0.429 and 0.5 in the group of our Braak and Braak AD stage V and VI individuals as compared with 0.059, 0.765 and 0.177 in our group of Braak and Braak AD stage 0 and I individuals. As expected, the frequency of the APOE ε4 allele in our group of Braak and Braak AD stage V and VI individuals (50%) was higher than in our group of Braak and Braak AD stage 0 and I individuals (17.7%), indicating the ε4 allele conferred increased risk for the development of AD 24, 34.

AD‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology in subcortical nuclei with efferent projections to the transentorhinal and entorhinal regions in Braak and Braak AD stages V and VI

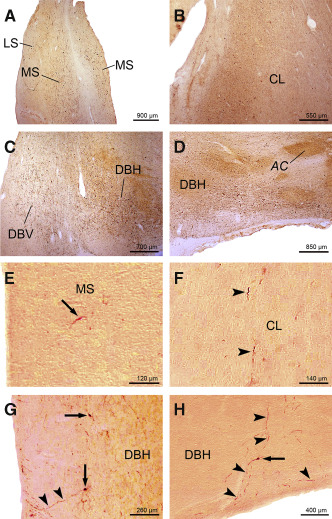

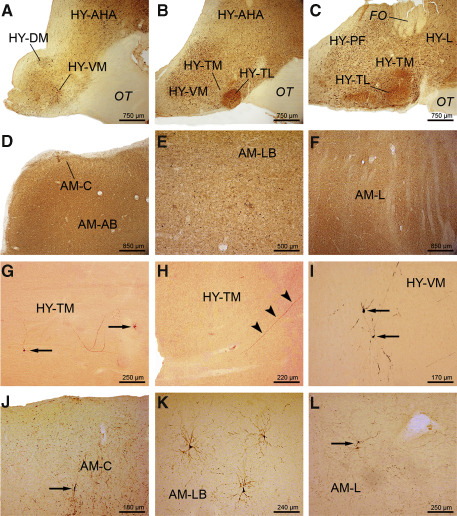

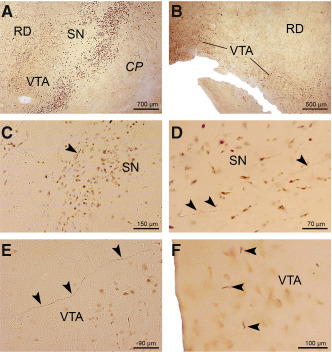

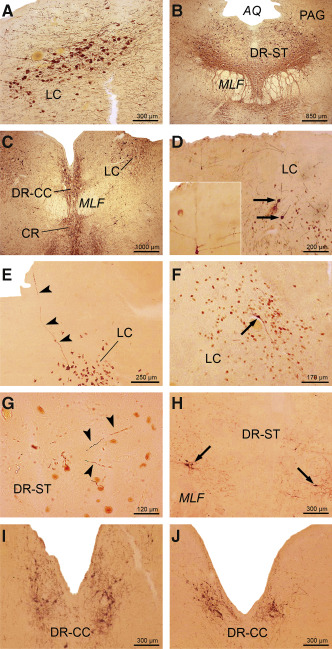

In all Braak and Braak AD stage V or VI individuals, all of the subcortical nuclei with efferent projections to the transentorhinal and entorhinal regions showed a marked to serious AT8‐immunoreactive tau pathology (Figure 1A–C; Figure 2A–F; Figure 3A–C; Figure 4A,B; Figure 5A–C; Supporting Information Figure S6A–C; Supporting Information Figure S7A–D; Supporting Information Figure S8A–C). Because of the even distribution of tau immunoreactive nerve cells throughout the affected subcortical nuclei, their localization in the brain and anatomical outlines were readily identifiable in the AT8‐immunolabeled tissue sections.

Figure 1.

AT8 ‐immunoreactive A lzheimer's disease ( AD )‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology in the medial septal nucleus, claustrum, and in the nuclei of the vertical and horizontal limbs of the diagonal band of B roca. A. Advanced AD‐related tau pathology in the medial septal nucleus (MS) of a 73‐year‐old female Braak and Braak stage V individual (case 2; Supporting Information Table S2). B. The AD‐related tau immunoreactive pathology in the claustrum (CL) of a 73‐year‐old female Braak and Braak stage V individual (case 2; Supporting Information Table S2). C. Severe AD‐related cytoskeletal pathology in the nucleus of the vertical limb of the diagonal band of Broca (DBV) of a 73‐year‐old female Braak and Braak stage V individual (case 2; Supporting Information Table S2). Note the additional severe involvement of the nucleus of the horizontal limb of the diagonal band of Broca (DBH). D. Severely involved DBH of a 76‐year‐old male Braak and Braak stage V individual (case 6; Supporting Information Table S2). E. AT8‐immunoreactive nerve cell in the MS (arrow) of a representative 35‐year‐old male Braak and Braak stage I individual (case 6; Supporting Information Table S1, Table 1). F. Tau immunoreactive long nerve cell process in the CL (arrowheads) of a typical 45‐year‐old female Braak and Braak stage I individual (case 12; Supporting Information Table S1, Table 1). G. AT8‐immunoreactive nerve cell perikarya (arrows) and long nerve cell process (arrowheads) in the DBV of a representative 45‐year‐old female Braak and Braak stage I individual (case 12; Supporting Information Table S1, Table 1). Note that the tau immunoreactive nerve cell process indicated by arrowheads extends to the wall of the third ventricle. H. AT8‐immunoreactive nerve cell perikaryon (arrow) and nerve cell processes (arrowheads) in the DBH of a representative 65‐year‐old male Braak and Braak stage I individual (case 16; Supporting Information Table S1, Table 1). This figure shows that tau immunoreactive processes of DBH nerve cells can extend to the subarachnoidal space. Abbreviations: AC = anterior commissure; AD = Alzheimer's disease; CL = claustrum; DBH = nucleus of the horizontal limb of the vertical band of Broca; DBV = nucleus of the vertical limb of the diagonal band of Broca; LS = lateral septal nucleus; MS = medial septal nucleus.

Figure 2.

AT8 ‐immunoreactive A lzheimer's disease ( AD )‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology in the hypothalamus and amygdala. A. Severe AT8‐immunoreactive tau cytoskeletal pathology in the hypothalamic ventromedial (HY‐VM) and dorsomedial nuclei (HY‐DM) of a 73‐year‐old female Braak and Braak stage V individual (case 6; Supporting Information Table S2). B. The AD‐related cytoskeletal pathology in the rostral hypothalamic tuberomamillary nucleus (HY‐TM) and hypothalamic ventromedial nucleus (HY‐VM) and (C) in the mid‐portion of the HY‐TM, perifornical hypothalamic region (HY‐PF) and in the hypothalamic lateral area (HY‐L) of the same Braak and Braak stage V individual (case 6; Supporting Information Table S2). The tau immunoreactive cytoskeletal pathology in (D) the cortical nucleus (AM‐C) and accessory basal nucleus of the amygdala (AM‐AB), (E) laterobasal nucleus of the amygdala (AM‐LB) and (F) lateral nucleus of the amygdala (AM‐L) of a 76‐year‐old male Braak and Braak stage V individual (case 6; Supporting Information Table S2). AT8‐immunoreactive (G) nerve cells (arrows) and (H) long ascending process (arrowheads) in the hypothalamic HY‐TM of a representative 44‐year‐old male Braak and Braak stage I case (case 11; Supporting Information Table S1). I. AT8‐immunolabeled nerve cells (arrow) in the hypothalamic HY‐VM of a representative 65‐year‐old male Braak and Braak stage I case (case 16; Supporting Information Table S1, Table 3). AT8‐immunoreactive nerve cells in (J) the AM‐C (arrow), (K) AM‐LB and (L) AM‐L (arrow) of a typical 21‐year‐old female Braak and Braak stage I case (case 4; Supporting Information Table S1). Abbreviations: AD = Alzheimer's disease; AM‐AB = accessory basal nucleus of the amygdala; AM‐C = cortical nucleus of the amygdala; AM‐L = lateral nucleus of the amygdala; AM‐LB = laterobasal nucleus of the amygdala; FO = fornix; HY‐AHA = anterior area of the hypothalamus; HY‐DM = dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus; HY‐PF = perifornical region of the hypothalamus; HY‐TL = tuberal lateral nucleus of the hypothalamus; HY‐TM = tuberomamillary nucleus of the hypothalamus; HY‐VM = ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus; OT = optic tract.

Figure 3.

AT8‐immunoreactive Alzheimer's disease (AD)‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology in the thalamic laterodorsal and subparafascicular nuclei, as well as in the midbrain peripeduncular nucleus. Well‐developed AT8‐immunoreactive tau cytoskeletal pathology (A) in the thalamic laterodorsal nucleus (LD) of a 73‐year‐old female Braak and Braak stage V individual (case 2; Supporting Information Table S2), and (B) in thalamic subparafascicular nucleus (SPF) of a 76‐year‐old male Braak and Braak stage V individual (case 6; Supporting Information Table S2). Note the additional affection of the thalamic parafascicular (PF) and paraventricular (PV) nuclei. C. Severe tau pathology in the peripeduncular nucleus (PP) of a 65‐year‐old male Braak and Braak stage VI individual (case 16; Supporting Information Table S2). D. Tau immunoreactive nerve cell process (arrow) in the thalamic LD of a typical 24‐year‐old female Braak and Braak stage 0 individual (case 2; Supporting Information Table S1, Table 2). E. AT8‐immunoreactive perikaryon of a nerve cell (arrow) in the thalamic laterodorsal nucleus (LD) of a representative 65‐year‐old male Braak and Braak stage I individual (case 16; Supporting Information Table S1, Table 2). F. Completely tau immunolabeled SPF nerve cell (arrow) of a representative 42‐year‐old male Braak and Braak stage 0 individual (case 3; Supporting Information Table S1, Table 2). G. AT8‐immunoreactive nerve cell perikarya (arrows) and nerve cell process (arrowheads) in the thalamic subparafascicular nucleus (SPF) of a representative 48‐year‐old male Braak and Braak stage I individual (case 15; Supporting Information Table S1, Table 2). H. AT8‐immunoreactive nerve cell processes (arrows) in the midbrain peripeduncular nucleus (PP) of a representative 39‐year‐old male Braak and Braak stage I individual (case 9; Supporting Information Table S1, Table 2). Abbreviations: AD = Alzheimer's disease; CM = centromedian thalamic nucleus; CP = cerebral peduncle; LD = laterodorsal thalamic nucleus; MD = mediodorsal thalamic nucleus; PF = parafascicular thalamic nucleus; PP = peripeduncular nucleus; PV = paraventricular thalamic nucleus; SN = substantia nigra; SPF = subparafascicular thalamic nucleus.

Figure 4.

AT8‐immunoreactive Alzheimer's disease (AD)‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology in the dopaminergic substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area. AT8‐immunoreactive tau cytoskeletal pathology (A) in the dopaminergic compact part of the substantia nigra (SN) and (B) ventral tegmental area (VTA) of a representative 75‐year‐old male Braak and Braak stage VI individual (case 4; Supporting Information Table S2). C. AT8‐immunoreactive neuronal tau pathology in nerve cell processes (arrowhead) in the dopaminergic compact part of the substantia nigra (SN) of a representative 24‐year‐old female Braak and Braak stage 0 individual (case 3; Supporting Information Table S1, Table 2). D. Long AT8‐immunoreactive nerve cell processes (arrowheads) between neuromelanin containing nerve cells in the dopaminergic compact part of the substantia nigra (SN) of a representative 44‐year‐old male Braak and Braak stage I individual (case 11; Supporting Information Table S1, Table 2). E. Tau immunoreactive pathology in the dopaminergic ventral tegmental area (VTA) (arrowheads) of a representative 24‐year‐old female Braak and Braak stage 0 individual (case 3; Supporting Information Table S1, Table 2). F. Short AT8‐immunolabeled nerve cell processes of neuromelanin containing nerve cells in the caudal linear nucleus of the dopaminergic ventral tegmental area (VTA) (arrowheads) of a representative 21‐year‐old female Braak and Braak stage I individual (case 4; Supporting Information Table S1, Table 2). Abbreviations: AD = Alzheimer's disease; CP = cerebral peduncle; RD = red nucleus; SN = substantia nigra; VTA = ventral tegmental area.

Figure 5.

AT8‐immunoreactive Alzheimer's disease (AD)‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology in the supratrochlear and caudal compact parts of the dorsal raphe nucleus and in the locus coeruleus. Severe AT8‐immunoreactive tau cytoskeletal pathology in (A) the locus coeruleus (LC) of a 76‐year‐old male Braak and Braak stage VI individual (case 6; Supporting Information Table S2) and (B) in the supratrochlear part of the dorsal raphe nucleus (DR‐ST) of a 73‐year‐old female Braak and Braak stage V individual (case 2; Supporting Information Table S2). Note the tau immunoreactive nerve cells in the periaqueductal gray (PAG). C. The tau immunoreactive cytoskeletal pathology in the caudal compact part of the dorsal raphe nucleus (DR‐CC) of a Braak and Braak stage V individual (case 2; Supporting Information Table S2). Note the additionally involved LC. D. AT8‐immunoreactive nerve cells (arrows) in the LC of a representative 21‐year‐old male Braak and Braak stage 0 individual (case 1; Supporting Information Table S1, Table 2) and (E) tau immunoreactive process of a LC nerve cell of a typical 45‐year‐old male Braak and Braak stage I individual (case 13; Supporting Information Table S1, Table 2). Inset in (D) shows AT8‐immunoreactive LC nerve cell with processes reaching the ependyma of the fourth ventricle. F. Tau immunoreactive nerve cell (arrow) in the LC of a typical 39‐year‐old male Braak and Braak stage I individual (case 9; Supporting Information Table S1, Table 2). G. AT8 immunopositive nerve cell processes in the DR‐ST (arrowheads) of a representative 24‐year‐old female Braak and Braak stage 0 individual (case 2; Table 1). H. Numerous AT8‐immunoreactive nerve cells (arrows) in the supratrochlear part of the dorsal raphe nucleus (DR‐ST) of a representative 45‐year‐old female Braak and Braak stage I individual (case 12; Supporting Information Table S1, Table 2). I. Numerous AT8‐immunoreactive nerve cells in the DR‐CC of a representative 24‐year‐old female Braak and Braak stage 0 individual (case 2; Supporting Information Table S1, Table 2) and (J) in the DR‐CC of a typical 65‐year‐old male Braak and Braak stage I individual (case 16; Supporting Information Table S1, Table 2). Abbreviations: AD = Alzheimer's disease; AQ = aqueduct; CR = central raphe nucleus; DR‐CC = dorsal raphe nucleus, compact caudal part; DR‐ST = dorsal raphe nucleus, supratrochlear part; LC = locus coeruleus; PAG = periaqueductal gray; MLF = medial longitudinal fascicle.

AD‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology in subcortical brain sites with efferent projections to the transentorhinal and entorhinal regions in Braak and Braak AD stage 0

Despite careful investigation, no AT8‐immunoreactive AD‐related tau pathology was observed in the allocortical transentorhinal and entorhinal regions of our three Braak and Braak AD stage 0 individuals. However, these individuals consistently showed AT8‐immunoreactive AD‐related tau pathology (Tables 1 and 2) in all cholinergic nuclei of the basal forebrain (Supporting Information Figure S6E,F), the claustrum, in select nuclei of the thalamus (central medial, laterodorsal, subparafascicular, central lateral nuclei, medial pulvinar and limitans–suprageniculate complex) (Figure 3D,F; Supporting Information Figure S7E,G; Supporting Information Figure S8D) and hypothalamus (ventromedial, tuberomamillary and supramammillary nuclei, perifornical and lateral regions), as well as in the midbrain (peripeduncular nucleus, dopaminergic substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area, periaqueductal gray, supratrochlear part of the dorsal raphe nucleus) (Figure 4C,E; Figure 5G) and pons (compact caudal part of the dorsal raphe nucleus, locus coeruleus, parabrachial nuclei) (Figure 5D,I). Notably, the subnuclei of the amygdala with efferent projections to the transentorhinal and entorhinal regions were either spared or only inconsistently affected at Braak and Braak stage 0 (Table 1). In all Braak and Braak AD stage 0 individuals, the AT8‐immunoreactive cytoskeletal pathology in the cholinergic basal forebrain nuclei and claustrum was present in the perikarya and processes of affected nerve cells. In the affected nuclei of the amygdala and hypothalamus, as well as in the majority of their involved thalamic and brainstem nuclei, the tau cytoskeletal pathology was confined to nerve cell processes (Tables 1 and 2),

AD‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology in subcortical brain sites with efferent projections to the transentorhinal and entorhinal regions in Braak and Braak AD stage I

In all of the Braak and Braak AD stage I cases studied, all of the subcortical nuclei studied exhibited AT8‐immunoreactive nerve cells (Figure 1E–H; Figure 2G–L; Figure 3E,G,H; Figure 4D,F; Figure 5E,F,H,J; Supporting Information Figure S6D,G,H; Supporting Information Figure S7F,H; Supporting Information Figure S8E–H; Tables 1 and 2) along with a few AT8‐immunoreactive projection nerve cells in the pre‐alpha layer of the allocortical transentorhinal and entorhinal regions. The AT8 immunoreactivity was either found in the perikarya of affected nerve cells (Figure 3E), or in their perikarya and proximal processes and dendritic trees (Figure 1E,G,H; Figure 2G,I–L; Figure 3F,G; Figure 5F,H–J; Supporting Information Figure S6D,G,H; Supporting Information Figure S7F,H; Supporting Information Figure S8E,G,H), but also occurred as isolated short, thick, swollen or club‐shaped nerve cell processes (Tables 1 and 2). Most of the AT8‐immunoreactive nerve cell processes were thin, slender, filamentous, elongated, serpentine or sausage‐like (Figure 1E–H; Figure 2G–L; Figure 3D,F–H; Figure 4C–F; Figure 5D–J; Supporting Information Figure S6D–H; Supporting Information Figure S7E–H; Supporting Information Figure S8D–H). Frequently, the nerve cell processes containing hyperphosphorylated tau could be traced up to the brain surface and adjacent ventricular surface or subarachnoidal space (Figure 1G,H; Figures 5D,E and 6; Supporting Information Figure S6G). In the claustrum, dopaminergic substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area, the medial pulvinar and limitans–suprageniculate complex of the thalamus, AT8‐immunoreactive nerve cells were selectively present at those topographical subunits from which projections to the transentorhinal and entorhinal regions were shown to originate in nonhuman primates 45.

In the majority of the Braak and Braak AD stage I individuals, the affected nerve cells in the cholinergic basal forebrain nuclei, claustrum and amygdala showed tau immunoreactivity in both their perikarya and processes (Table 1). In one‐half of the Braak and Braak AD stage I individuals, the tau immunoreactive cytoskeletal changes were also simultaneously present in the perikarya and processes of affected hypothalamic nerve cells, whereas in the thalamus and brainstem the affected nerve cells of most individuals displayed only tau immunoreactivity in their processes (Tables 1 and 2).

In all of the Braak and Braak stage 0 and I individuals studied, the nuclei immediately adjacent to the subcortical brain sites with efferent projections to the transentorhinal and entorhinal regions (eg, striatum, pallidum, thalamic ventral anterior, ventrolateral and mediodorsal nuclei, thalamic medial and lateral geniculate bodies) (Supporting Information Figures S1–5) were free of AT8‐immunoreactive nerve cells.

Related tissue changes

In all of our Braak and Braak AD stage 0, I, V and VI individuals, no PD‐related immunoreactive LB and/or LN or abnormal TDP‐43 nerve or glial cell aggregations were detected. In addition, except of one Braak and Braak AD stage I individual who showed some neocortical ß‐amyloid deposits corresponding to phase 1 of the AD‐related brain ß‐amyloidosis 93 (case 10; Supporting Information Table S1), no brain ß‐amyloid deposits were observed in our Braak and Braak AD stage 0 and I individuals.

The brain ß‐amyloidosis of our Braak and Braak AD stage V individuals corresponded to phase 3 (case 5; Supporting Information Table S2), phase 4 (cases 2 and 7; Supporting Information Table S2) or phase 5 (cases 3 and 6; Supporting Information Table S2) of the AD‐related brain ß‐amyloidosis and in our Braak and Braak AD stage VI individuals to phase 3 (case 1; Supporting Information Table S1) or phase 4 (case 4; Supporting Information Table S2) 93.

Statistical analysis

Calculation of the weighted kappa coefficient revealed a high inter‐rater reliability and a substantial agreement between UR and KS regarding the detection of AT8‐immunoreactive nerve cell perikarya or processes (Κw = 0.76; P < 0.0001).

Discussion

Early AD‐related cytoskeletal pathology in the subcortical nuclei with efferent projections to the allocortical transentorhinal and entorhinal regions

In the present study, we demonstrate the very early and substantial AT8‐immunoreactive tau cytoskeletal pathology in the subcortical nuclei with efferent projections to the allocortical transentorhinal and entorhinal regions in individuals with Braak and Braak stage 0 or I AD‐related cortical cytoskeletal pathology (Supporting Information Figures S1–S5). All of these affected nuclei are important relay stations in the circuits of the limbic system of the human brain, are highly interconnected anatomically via fiber tracts 1, 7, 13, 41, 42, 54, 60, 63, 64, 66, 69, 75, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 94, 98, are classically recognized as being highly vulnerable to and bear the brunt of the immunoreactive brain tau cytoskeletal pathology in demented AD patients burdened by AD‐related Braak and Braak AD stage V or VI cortical tau cytoskeletal pathology 2, 3, 15, 18, 29, 33, 40, 56, 57, 67, 72, 73, 80, 82, 83, 84, 86, 87, 88, 89 (Supporting Information Figures S1–S5). The present study not only confirms the exceptional high vulnerability and severe affection of these subcortical nuclei during the final stages of the evolution of the AD‐related cytoskeletal pathology (ie, Braak and Braak AD stages V and VI). It also demonstrates for the first time (i) that all of these subcortical nuclei are very early affected by the immunoreactive tau pathology during the initial stages of the evolution of the AD‐related cytoskeletal pathology, and (ii) that the extent of the subcortical tau cytoskeletal pathology present in Braak and Braak AD stages 0 and I has been considerably underestimated in the past 13, 14, 18, 21, 29, 39, 80, 82, 83, 84, 88, 89.

Although the intraneuronal tau pathology and the extracellular deposits of the insoluble β‐amyloid protein apparently belong to the same underlying disease process and represent two sides of the same coin, the present study (i) was intended to provide new insights into the early evolution of the AD‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology and (ii) was not designed to elucidate the enigmatic association between the appearance of the AD‐related neuronal and extraneuronal deposits. This association was specified many years ago in the “amyloid cascade theory,” which postulated that an increase in β‐amyloid secretion and subsequent extraneuronal aggregation of this protein in the diseased brains induces and triggers a cascade of deleterious changes which ultimately lead to the development of the AD‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology and neuronal death. In all of our Braak and Braak AD stage 0 individuals and 13 of our Braak and Braak AD stage I individuals, subcortical cytoskeletal changes occurred in the absence of any brain β‐amyloid deposits. Together with the findings of a number of previous morphological investigations, these findings give rise to additional doubts regarding the validity of the “amyloid cascade theory” and support the opinion that the accumulations of the β‐amyloid protein do not represent the initial AD‐related pathological alterations which secondarily provoke the appearance of the AD‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology 18, 29, 39, 79.

The presence of the APOE ε4 allele is a well‐established risk factor for the development of AD 24, 34. Consistent with prevailing assumptions, our findings show an increased prevalence of the APOE ε4 allele in our Braak and Braak AD stage V and VI individuals implicating ε4 allele as a strong risk marker for the development of AD.

Recently, it has been suggested to create a separate neurodegenerative disease entity called PART (ie, primary age‐associated tauopathy), which has been considered to occur independent from AD and includes individuals with a tau cytoskeletal pathology more or less confined to the allocortical entorhinal region and hippocampus either without or minimal β‐amyloid deposits in the brain 28, 53. Although the subcortical tau pathology that may occur in PART currently is incompletely known and described 53, considering the new concept of PART one may be inclined to regard the early tau pathology described in the present study as a manifestation of PART. For the following reasons, however, we regard the early subcortical immunoreactive Braak and Braak stage 0 and I tau pathologies observed in our study as an integral component of the AD continuum rather as a part of a separate disease entity or tauopathy. These subcortical pathologies are confined to the subcortical nuclei with efferent projections to the transentorhinal and entorhinal regions all of which are well known to undergo severe tau cytoskeletal pathology in demented AD patients burdened by Braak and Braak AD stage V or VI tau cytoskeletal pathologies 2, 3, 15, 18, 29, 33, 40, 56, 57, 69, 72, 73, 82, 83, 84, 86, 88. As the topographical distribution of the early subcortical Braak and Braak AD stage 0 and I tau cytoskeletal pathology documented in our study represents a mirror of the subcortical distribution pattern of the full‐blown subcortical AD‐related cytoskeletal pathology in Braak and Braak AD stages V and VI, it is hard to imagine that the selective and early affection of the subcortical nuclei with efferent projections to the transentorhinal and entorhinal regions is purely by chance. Instead, because of the very close correlation between the anatomical distribution patterns of the subcortical cytoskeletal pathology in Braak and Braak AD stages 0 and I and that in Braak and Braak AD stages V and VI, it appears more plausible that the very early tau cytoskeletal pathology of the subcortical nuclei with efferent projections to the transentorhinal and entorhinal regions in contrast to the allocortical tau cytoskeletal pathology 53 can serve as a predictor of the progress of the underlying disease process to fully developed AD. In addition, this forerunner role of the early subcortical cytoskeletal pathology is supported by the fact that the mean ages at death of our Braak and Braak AD stage I individuals and that of the Braak and Braak AD stage V and VI individuals differed by 30 years, and that this time period of 30 years is in good agreement with the estimated time interval, which the continuous disease process needs for its progression from Braak and Braak AD stages I–V 83.

For a long time, the allocortical transentorhinal or entorhinal regions were considered as the first and sole brain regions that display AD‐related cytoskeletal pathology already in Braak and Braak AD stage I, and it has been suggested that the AD‐related cortical cytoskeletal pathology spreads to other brain regions that become affected in later Braak and Braak AD stages 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 30, 59. According to recent epidemiological estimations, we have to assume that the in vivo transition from the Braak and Braak AD stage I to stage II takes several years 29, 31, 83. Therefore, the concomitant presence of the tau cytoskeletal pathology in subcortical nuclei sending efferent projections to the transentorhinal and entorhinal regions and in their allocortical projection targets in the brains of individuals with neuropathological Braak and Braak AD stage I does not allow to distinguish whether the vulnerability of the brain areas follows a simultaneous or a sequential temporal pattern in vivo with one of these brain sites presenting the initial and the other the secondarily induced AD‐related tau pathologies 39, 83.

Subcortical origin and ascending propagation of the AD‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology

In addition to the consistent affection of all subcortical nuclei with efferent projections to the allocortical transentorhinal and entorhinal regions in individuals with Braak and Braak stage I AD‐related cortical tau cytoskeletal pathology, the present pathoanatomical study also demonstrates a considerable immunoreactive tau pathology in a subset of these limbic nuclei in three individuals devoid of AD‐related cortical cytoskeletal pathology (ie, Braak and Braak AD stage 0) (Figures 3D,F, 4C,E and 5D,G,I; Supporting Information Figure S6E,F; Supporting Information Figure S7E,G; Supporting Information Figure S8D). The consistent involvement of a subset of these subcortical limbic nuclei (ie, medial septal nucleus, nuclei of the vertical and horizontal limbs of the diagonal band of Broca, basal nucleus of Meynert; claustrum; hypothalamic ventromedial, tuberomamillary and supramammillary nuclei, perifornical region and lateral area; thalamic central medial, laterodorsal, subparafascicular, and central lateral nuclei, medial pulvinar and limitans–suprageniculate complex; peripeduncular nucleus, dopaminergic substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area, periaqueductal gray, midbrain and pontine dorsal raphe nuclei, locus coeruleus, and parabrachial nuclei) by the AD‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology in the absence of any tau immunoreactive cytoskeletal pathology in the allo‐ or neocortex (ie, precortical Braak and Braak stage 0 in the evolution of the AD‐related tau pathology) supports the concept that the subcortical nuclei under consideration play an important pathophysiological role in the initial stage of the disease process of AD and may represent the port of entry from which the AD‐related cytoskeletal pathology ascends toward the cerebral allocortex. This concept is based on the following hypotheses about the development of the AD‐related cytoskeletal pathology during the disease progression: (i) the AD‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology originates in subcortical brain sites, in which the first nerve cells in the brain sustain accumulations of the hyperphosphorylated cytoskeletal protein tau 39, 83, 89; (ii) the AD‐related cytoskeletal pathology develops first and only in nerve cells of anatomically interconnected cortical and subcortical regions of select functional systems and networks of the human brain 19, 25, 29, 33, 55, 59, 71, 72, 73, 78, 87, 89, 96; (iii) the anatomical interconnectivities of a given cortical or subcortical brain region establish its vulnerability for or resistance to the AD‐related cytoskeletal pathology 83, 89; and (iv) the pathological process underlying the AD‐related cytoskeletal pathology uses these anatomical pathways and interconnectivities for its transneuronal spread throughout the brain 18, 25, 29, 33, 39, 55, 59, 71, 72, 78, 83, 96.

Transneuronal spread of the AD‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology

The evolution and progressive expansion of the AD‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology in the human brain are not a random or arbitrary process, but (i) target only select subcortical nuclei, layers and areas of the cerebral cortex, (ii) follow highly predictable chronological and spatial sequences, and (iii) ultimately lead to a stereotypical topographic brain progression and characteristic nuclei‐specific, area‐specific, layer‐specific and cell‐type‐specific distribution pattern in the diseased brain 4, 11, 14, 15, 16, 18, 33, 44, 55, 65, 86, 89. Explaining the highly stereotypical targeting and propagation of the AD‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology is still one of the most important and enduring challenges in clinical neuroscience worldwide and remains the first‐rate goal of contemporary and future AD research 87. Previous explanations for the high vulnerability of select cortical and subcortical brain sites were either based on their anatomical affiliation to the limbic system, their integration into specific brain neurotransmitter systems, the specific molecular biochemical phenotypes of the affected nerve cells, or on the low degree or absence of myelinization of the particular long axons of their affected nerve cells 12, 16, 18, 27, 78, 96.

More and more evidence points to the anatomical interconnectivities of a given brain region (i) as a pivotal factor accounting for its susceptibility for or resistance to the AD‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology, and (ii) as the structural base for its strikingly well‐ordered and stereotypical progressive brain expansion and characteristic distribution pattern 18, 25, 29, 33, 39, 68, 78, 83, 87, 89, 96. Although the exact basic molecular mechanisms of the disease still are unclear, many renowned researchers in the field favor the pathomechanistic hypothesis that the degenerative process of the AD‐related cytoskeletal pathology (i) follows anatomical pathways for its brain propagation, (ii) spreads transneuronally via these pathways in predictable, interindividually consistent chronological and topographical sequences, and (iii) leads to a stereotypical and specific brain distribution pattern of the immunoreactive tau pathology which represents an exact mirror of the complex anatomical interconnectivities within the brain networks and circuits involved 27, 29, 33, 55, 58, 65, 68, 71, 89, 96.

Although these pathomechanistic hypotheses are currently widely held, further empirical evidence can only strengthen the underlying theoretical concept. The subcortical nuclei consistently affected in our Braak and Braak AD stage 0 and I individuals by the immunoreactive tau pathology share common allocortical projection targets (ie, transentorhinal and entorhinal regions) 45, 61, are intimately interconnected with each other via reciprocal brain fiber tracts 1, 7, 13, 42, 54, 63, 64, 66, 69, 75, 80, 81, 85, 94, 98, and receive substantial afferent input from or project to the midbrain raphe nuclei 41, 60, 63, 64, 69, 75, 80, 81. Accordingly, the findings of the present post‐mortem AD study are in agreement with these pathoanatomical hypotheses and meta‐analytical considerations and point to the pivotal role of intact anatomical interconnectivities for the ascend of the AD‐related cytoskeletal pathology toward the cerebral cortex and its highly predictable and well‐ordered chronological and topographic spread 27, 29, 33, 55, 58, 65, 71, 89, 96.

To the best of our knowledge, Saper et al were among the first neuroscientists who recognized and pointed to the strikingly well‐ordered, predictable chronological and topographical sequential orders of the spread of the AD‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology and tried to explain this stereotypical propagation with a transneuronally spread of the underlying disease process 87. This firstly very abstractly formulated and ill‐defined idea of a transneuronal propagation of the AD‐related cytoskeletal pathology, however, has been recently specified and supplemented by the proposal that (i) AD may be among the diseases sharing prion‐like pathological mechanisms and (ii) that the directed brain spread of the AD‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology via neuron‐to‐neuron transmission and transsynaptic transport from affected neurons to anatomically interconnected healthy nerve cells may follow a prion‐like corruptive protein templating and seeding‐like pathomechanism which induces the templated misfolding, self‐aggregation and propagation of the altered tau protein within the framework of an injurious autocatalytic cascade of pathological events 36, 50, 55, 70, 71, 79, 96.

Human neurodegenerative protein misfolding diseases assigned to the so‐called “prion‐like” diseases are characterized neuropathologically by their start in circumscribed brain areas, the directed, transneuronal spread and stereotypical brain propagating of the underlying disease process in predictable sequences along anatomical pathways, as well as by molecular pathological mechanisms in the initiation, proliferation, intercellular transfer and spread of insoluble “non‐prion” aggregates of the aberrantly conformed and misfolded disease protein that are reminiscent to that of proper prion diseases 5, 36, 55, 71, 76, 79, 95. Although the presumed start of AD in circumscribed subcortical brain regions and the possible targeted transneuronal spread of its underlying disease process along anatomical pathways may be in support of the currently prevailing idea of AD as a chronic prion‐like neurodegenerative disease, further studies are required to substantiate this new scientific approach and to prove unequivocally the suggested prion‐like nature and behavior of the hyperphosphorylated tau protein 36, 50, 55, 70, 71, 79, 96.

Implications of the early subcortical AD‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology for the modified Braak and Braak AD staging system

The subcortical AD‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology for a long time has been regarded as a secondary phenomenon that takes place subsequent to and is triggered by the involvement of the cerebral cortex and has such attracted only minor attention in previous neuropathological AD research 12, 18, 30, 33, 73. The worldwide practiced Braak and Braak staging procedure of the AD‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology relates to the distribution, extent and progression of this pathology in the cerebral cortex and represents an acknowledged, simple and reliable procedure for the rapid post‐mortem assessment of the distribution and degree of the AD‐related cortical tau pathology upon diagnostic neuropathological examination 9, 10, 13, 14, 16, 18, 29, 30, 31, 43, 44, 52, 58, 59, 65. Moreover, the Braak and Braak AD staging system correlates well with the progressive cognitive impairments of AD patients 9, 10, 18, 30, 52, 59, 79. Although the original staging system has been recently revised, our preliminary findings indicated that the very early subcortical tau cytoskeletal pathology in addition to the pontine locus coeruleus may also affect a large variety of other subcortical nuclei with projections to the early affected allocortical entorhinal and transentorhinal regions 13, 14, 18, 21, 29. The results of the present pathoanatomical study confirmed our initial impressions and showed that the extent of the very early AD‐related subcortical tau cytoskeletal pathology of individuals with Braak and Braak AD stage 0 or I has been considerably underestimated in the past and is clearly more widespread than believed so far. In view of their potential pathogenetic relevance 39, 83, 89 and the widespread distribution of the very early AD‐related subcortical tau cytoskeletal pathology observed in our Braak and Braak AD stage 0 individuals, we suggest to reevaluate the modified Braak and Braak AD stages and to perform further cross‐sectional studies of a large cohort of individuals with Braak and Braak AD stage 0 cytoskeletal pathology with the goal to establish the real extent of the very early precortical phase subcortical tau cytoskeletal pathology 18, 21. These additional cross‐sectional studies may also help (i) to further parcellate the precortical Braak and Braak AD stage 0 into sequential phases in the early evolution of the AD‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology, (ii) to stepwise narrow down the true portal of entry of the disease process underlying AD, and (iii) ultimately facilitate the identification of the initial cascades of pathological events leading to the first AD‐related tau cytoskeletal changes and their exact brain location 39, 50.

Considering the presumably long preclinical phase of AD of approximately 30–40 years, unequivocal identification of the exact brain location of the first AD‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology by improved in vivo imaging techniques could (i) lead to the establishment of a reliable biomarker for AD onset and (ii) open a window of therapeutical opportunities that extends practically the whole lifetime of affected individuals 18, 22, 23, 47, 68. These subcortical brain sites with the first AD‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology most likely represent the induction sites of the pathological process of AD, which, once started, spreads transneuronally via anatomical pathways in highly predictable, interindividually consistent chronological and topographical sequences throughout the brain. Therefore, these subcortical induction sites should be envisaged as the first therapeutic intervention targets for imaging‐guided immunotherapies capable to interrupt the transneuronal brain propagation of the AD‐related disease process 22, 23, 36, 39, 55. As the extent and distribution of the AD‐related cortical tau aggregation pathology correlates significantly with the evolution of the disease intrinsic dementia 9, 10, 11, 23, 29, 48, 49, 52, 55, 58, 59, 65, such early immunotherapeutical interventions may be suitable to effectively prevent dementia and other AD‐related disease symptoms several decades before their onset.

Disclosure Statement

All authors have no actual or potential conflicts of interest to disclose, including financial, personal or other relationships with other people or organizations, within 3 years of beginning the work submitted.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Schematized frontal section through the human brain at the level of the optic chiasm (OC).

Figure S2. Schematized frontal section through the human brain at the level of the hypothalamic tuberal region.

Figure S3. Schematized frontal section through the human brain at the level of the red nucleus (RD).

Figure S4. Schematized frontal section through the human brain at the level of the thalamic lateral (LGB) and medial geniculate bodies (MGB).

Figure S5. Schematized horizontal section through the mid level of the human pons.

Figure S6. AT8‐immunoreactive Alzheimer's disease (AD)‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology in the claustrum and basal nucleus of Meynert.

Figure S7. AT8‐immunoreactive Alzheimer's disease (AD)‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology in the thalamic central medial and paraventricular nuclei.

Figure S8. AT8‐immunoreactive Alzheimer's disease (AD)‐related tau cytoskeletal pathology in the thalamic central lateral nucleus, medial pulvinar and limitans–suprageniculate complex.

Table S1. Overview of the individuals with Braak and Braak stage I or 0 Alzheimer's disease (AD)‐related cortical tau cytoskeletal pathology.

Table S2. Overview of the individuals with Braak and Braak stage V or VI Alzheimer's disease (AD)‐related cortical tau cytoskeletal pathology.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Dr. Senckenbergische Stiftung (Frankfurt/Main, Germany). The skillful assistance of D. von Meltzer (secretary), C. Mauer (tissue cutting), I. Szasz (graphics) and H. Korff (APOE genotyping) is thankfully acknowledged. LTG is supported by NIH grants R01AG040311 and P50AG023501. The authors also like to thank Jean‐Paul Vonsattel (The New York Brain Bank/Taub Institute, The Presbyterian Hospital and Columbia University, New York, USA) for his critical revision of our manuscript and his valuable criticism and comments.

References

- 1. Aggleton JP, Burton MJ, Passingham RE (1980) Cortical and subcortical afferents to the amygdala of the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta). Brain Res 190:347–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Airaksinen MS, Paetau A, Paljarvi L, Reinikainen K, Riekkinen P, Suomalainen R, Punula P (1991) Histamine neurons in human hypothalamus: anatomy in normal and Alzheimer diseased brains. Neuroscience 44:465–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Airaksinen MS, Reinikainen K, Riekkinen P, Panula P (1991) Neurofibrillary tangles and histamine‐containing neurons in Alzheimer hypothalamus. Agents Actions 33:104–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Al‐Sarraj S, Bodi I, Bogdanovic N, Braak H et al (2008) Staging of neurofibrillary pathology in Alzheimer's disease: a study of the BrainNet Europe Consortium. Brain Pathol 18:484–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Alonso AC, Li B, Grundke‐Iqbal I, Iqbal K (2008) Mechanism of tau‐induced neurodegeneration in Alzheimer disease and related tauopathies. Curr Alzheimer Res 5:375–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alzheimer A (1907) Über eine eigenartige Erkrankung der Hirnrinde. Allg Z Psychiat Psych Gerichtl Med 64:146–148. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Amaral DG, Cowan WM (1980) Subcortical afferents to the hippocampal formation in the monkey. J Comp Neurol 189:573–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ballard C, Gauthier S, Corbett A, Brayne C, Aarsland D, Jones E (2011) Alzheimer's disease. Lancet 377:1019–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bancher C, Braak H, Fischer P, Jellinger KA (1993) Neuropathological staging of Alzheimer lesions and intellectual status in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease patients. Neurosci Lett 162:179–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bancher C, Jellinger K, Lassmann H, Fischer P, Leblhuber F (1996) Correlations between mental state and quantitative neuropathology in the Vienna Longitudinal Study on Dementia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 246:137–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Blennow K, de Leon MJ, Zetterberg H (2006) Alzheimer's disease. Lancet 368:387–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Braak E, Braak H, Mandelkow EM (1994) A sequence of cytoskeleton changes related to the formation of neurofibrillary tangles and neuropil threads. Acta Neuropathol 87:554–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Kretzschmar H, Del Tredici K (2006) Staging of Alzheimer disease‐associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol 112:389–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Braak H, Braak E (1991) Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer‐related changes. Acta Neuropathol 82:239–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Braak H, Braak E (1991) Alzheimer's disease affects limbic nuclei of the thalamus. Acta Neuropathol 81:261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Braak H, Braak E (1992) The human entorhinal cortex: normal morphology and lamina‐specific pathology in various diseases. Neurosci Res 15:6–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Braak H, Braak E, Yilmazer D, Bohl J (1996) Functional anatomy of human hippocampal formation and related structures. J Child Neurol 11:265–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Braak H, Del Trecidi K (2015) Neuroanatomy and pathology of sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol 215:1–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Braak H, Del Tredici K (2009) Neuroanatomy and pathology of sporadic Parkinson's disease. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol 201:1–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Braak H, Rüb U, Del Tredici K (2003) Involvement of precerebellar nuclei in multiple system atrophy. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 29:60–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Braak H, Thal DR, Ghebremedhin E, Del Tredici K (2011) Stages of the pathologic process in Alzheimer disease: age categories from 1 to 100 years. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 70:960–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brunden KR, Ballatore C, Crowe A, Smith AB III, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ (2010) Tau‐directed drug discovery for Alzheimer's disease and related tauopathies: a focus on tau assembly inhibitors. Exp Neurol 223:304–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brunden KR, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM (2009) Advances in tau‐focused drug discovery for Alzheimer's disease and related tauopathies. Nat Rev Drug Discov 8:783–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, Small GW et al (1993) Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer's disease in late onset families. Science 261:921–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. De Lacoste MC, White CL III (1993) The role of cortical connectivity in Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis: a review and model system. Neurobiol Aging 14:1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. De Vos KJ, Grierson AJ, Ackerley S, Miller CC (2008) Role of axonal transport in neurodegenerative diseases. Annu Rev Neurosci 31:151–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dickson DW (1997) Neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: a perspective from longitudinal clinicopathological studies. Neurobiol Aging 18:S21–S26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Duyckaerts C, Braak H, Brion JP, Buée L, Del Tredici K, Goedert M et al (2015) PART is part of Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol 129:749–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Duyckaerts C, Delatour B, Potier MC (2009) Classification and basic pathology of Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol 118:5–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Duyckaerts C, Hauw JJ (1997) Diagnosis and staging of Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Aging 18:S33–S42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Duyckaerts C, Hauw JJ (1997) Prevalence, incidence and duration of Braak's stages in the general population: can we know? Neurobiol Aging 18:362–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ferrer I (2012) Defining Alzheimer as a common age‐related neurodegenerative process not inevitably leading to dementia. Prog Neurobiol 97:38–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. German DC, White CL III, Sparkman DR (1987) Alzheimer's disease: neurofibrillary tangles in nuclei that project to the cerebral cortex. Neuroscience 21:305–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ghebremedhin E, Schultz C, Thal DR, Rüb U, Ohm TG, Braak E, Braak H (2001) Gender and age modify the association between APOE and AD‐related neuropathology. Neurology 56:1696–1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Goedert M (1993) Tau protein and the neurofibrillary pathology of Alzheimer's disease. Trends Neurosci 16:460–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Goedert M, Clavaguera F, Tolnay M (2010) The propagation of prion‐like protein inclusions in neurodegenerative diseases. Trends Neurosci 33:317–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Goedert M, Klug A, Crowther RA (2006) Tau protein, the paired helical filament and Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis 9:195–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gong CX, Grundke‐Iqbal I, Iqbal K (2010) Targeting tau protein in Alzheimer's disease. Drugs Aging 27:351–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Grinberg LT, Rüb U, Ferretti RE, Nitrini R, Farfel JM, Polichiso L et al (2009) The dorsal raphe nucleus shows phospho‐tau neurofibrillary changes before the transentorhinal region in Alzheimer's disease. A precocious onset? Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 35:406–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grudzien A, Shaw P, Weintraub S, Bigio E, Mash DC, Mesulam MM (2007) Locus coeruleus neurofibrillary degeneration in aging, mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging 28:327–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hornung JP (2003) The human raphe nuclei and the serotonergic system. J Chem Neuroanat 26:331–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hsu DT, Price JL (2009) Paraventricular thalamic nucleus: subcortical connections and innervation by serotonin, orexin, and corticotropin‐releasing hormone in macaque monkeys. J Comp Neurol 512:825–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hyman BT (1997) The neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: clinical‐pathological studies. Neurobiol Aging 18:S27–S32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hyman BT, Trojanowski JQ (1997) Consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer disease from the National Institute on Aging and the Reagan Institute Working Group on diagnostic criteria for the neuropathological assessment of Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 56:1095–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Insausti R, Amaral DG, Cowan WM (1987) The entorhinal cortex of the monkey: III. Subcortical afferents. J Comp Neurol 264:396–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Iqbal K, Grundke‐Iqbal I (2008) Alzheimer neurofibrillary degeneration: significance, etiopathogenesis, therapeutics and prevention. J Cell Mol Med 12:38–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Iqbal K, Grundke‐Iqbal I (2011) Opportunities and challenges in developing Alzheimer disease therapeutics. Acta Neuropathol 122:543–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Iqbal K, Liu F, Gong CX, Alonso AC, Grundke‐Iqbal I (2009) Mechanisms of tau‐induced neurodegeneration. Acta Neuropathol 118:53–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Iqbal K, Liu F, Gong CX, Grundke‐Iqbal I (2010) Tau in Alzheimer disease and related tauopathies. Curr Alzheimer Res 7:656–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Itzhaki RF, Wozniak MA, Appelt DM, Balin BJ (2004) Infiltration of the brain by pathogens causes Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging 25:619–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jalbert JJ, Daiello LA, Lapane KL (2008) Dementia of the Alzheimer type. Epidemiol Rev 30:15–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jellinger KA (2006) Alzheimer 100—highlights in the history of Alzheimer research. J Neural Transm 113:1603–1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Jellinger KA, Alafuzoff I, Attems J, Beach TG, Cairns NJ, Crary JF et al (2015) PART, a distinct tauopathy, different from classical sporadic Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol 129:757–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jones EG, Burton H, Saper CB, Swanson LW (1976) Midbrain, diencephalic and cortical relationships of the basal nucleus of Meynert and associated structures in primates. J Comp Neurol 167:385–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Jucker M, Walker LC (2011) Pathogenic protein seeding in Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Ann Neurol 70:532–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kromer Vogt LJ, Hyman BT, Van Hoesen GW, Damasio AR (1990) Pathological alterations in the amygdala in Alzheimer's disease. Neuroscience 37:377–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kuljis RO (1994) Lesions in the pulvinar in patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 53:202–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lace G, Savva GM, Forster G, de Silva R, Brayne C, Matthews FE et al (2009) Hippocampal tau pathology is related to neuroanatomical connections: an ageing population‐based study. Brain 132:1324–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lace GL, Wharton SB, Ince PG (2007) A brief history of tau: the evolving view of the microtubule‐associated protein tau in neurodegenerative diseases. Clin Neuropathol 26:43–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lavoie B, Parent A (1991) Serotoninergic innervation of the thalamus in the primate: an immunohistochemical study. J Comp Neurol 312:1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lei S (2012) Serotonergic modulation of neural activities in the entorhinal cortex. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol 4:201–210. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mandelkow E, Song YH, Schweers O, Marx A, Mandelkow EM (1995) On the structure of microtubules, tau, and paired helical filaments. Neurobiol Aging 16:347–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Mantyh PW (1983) Connections of midbrain periaqueductal gray in the monkey. I. Ascending efferent projections. J Neurophysiol 49:567–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mantyh PW (1983) Connections of midbrain periaqueductal gray in the monkey. II. Descending efferent projections. J Neurophysiol 49:582–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]