Abstract

Purpose

Inflow-vascular space occupancy (iVASO) measures arterial cerebral blood volume (aCBV) using accurate blood water nulling (TI) when arterial blood reaches the capillary, i.e., at the arterial arrival time. This work assessed the reproducibility of iVASO measurements in the hippocampus and cortex at multiple TIs.

Methods

The iVASO approach was implemented at multiple TIs in 10 healthy volunteers at 3T. aCBV values were measured at each TI in the left and right hippocampus, and the cortex. Reproducibility of aCBV measurements within scans (same day) and across sessions (different days) was assessed using the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC).

Results

Overall hippocampal aCBV was significantly higher than cortical aCBV, likely due to higher gray matter volume. Hippocampal ICC values were high at short TIs (≤914 ms; intra-scan values = 0.80–0.96, inter-scan values = 0.61–0.91). Cortically, high ICC values were observed at intermediate TIs of 914 (intra: 0.93, inter: 0.87) and 1034 ms (intra: 0.96, inter: 0.86). The ICC values were comparable to established contrast-based CBV measures.

Conclusion

iVASO measurements are reproducible within and across sessions. TIs for iVASO measurements should be chosen carefully, taking into account heterogeneous arterial arrival times in different brain regions.

Keywords: cerebral blood volume, cerebral blood flow, iVASO, reproducibility, hippocampus, cortex

INTRODUCTION

Cerebral blood volume (CBV; ml blood/100 g parenchyma) is an important physiological parameter generally coupled to cerebral perfusion. Altered hippocampal CBV is observed in multiple illnesses including Alzheimer’s disease and Schizophrenia and may be indicative of early functional impairment (1,2). It is likely that the extent to which autoregulatory mechanisms such as changes in CBV maintain CBF in early stages of disease are fundamental to understanding the sequela of functional brain changes and, in turn, for guiding management decisions (3–6). The most common approaches for measuring CBV require exogenous contrast agents, such as 99mTc SPECT, O-15 PET (3,7) or paramagnetic (e.g. gadolinium chelate) MRI (8–10). As these methods are invasive, longitudinal monitoring of patients (e.g., following therapy or pharmacological intervention) may be contraindicated due to dose restrictions, complicating the range of studies that can be pursued with such techniques.

Vascular space occupancy (VASO) approaches that use blood water as an endogenous contrast for CBV measurements were proposed in the last decade. While VASO was originally designed to evaluate the evoked CBV response, and to estimate relative CBV changes, variants such as inflow vascular space occupancy (iVASO) (11,12) and iVASO with dynamic subtraction (13) have more recently been proposed to quantify absolute arterial CBV (aCBV) (12–15). aCBV, which comprises approximately 20–30% of total CBV (16), specifically may be more relevant in many situations because it is the arterioles that undergo active vasoconstriction or vasodilation from vascular smooth muscles (17). Briefly, these approaches acquire two images: a null image with only tissue signal and a control image containing both tissue and blood signals (13). To achieve this, first the tissue and blood water magnetization is inverted over a large spatial volume, after which the magnetization in the imaging slice only is restored using a slice-selective inversion. The inverted blood water outside the imaging volume flows into the imaging volume while also undergoing T1 relaxation. The null volume is acquired at the inversion time (TI) when inflowing arterial blood water magnetization is zero. For a control image, a slice-selective inversion pulse inverts tissue and blood water magnetization only in the imaging volume. A second slice-selective inversion pulse immediately restores this magnetization (i.e. no net blood water inversion) and acquisition is performed after an identical delay, TI. Thus, the control volume contains both tissue and blood signal, and the null volume contains only tissue signal. Consequently, the difference image (control – null) contains signal from only arterial blood. The range of steady-state blood water nulling times for iVASO is generally in the range of 500–1100 ms, which is similar to the time for blood water to reach the capillary exchange site, and as such, the resulting image contains signal from primarily pre-capillary blood water.

The contrast origins of this approach and feasibility have been demonstrated in cortical gray matter, and the aCBV values obtained have been shown to be consistent with similar measures from dynamic susceptibility contrast MRI (12,13). While the inter-session reproducibility of multi-post-labeling delay ASL has recently been reported (18), the reproducibility of the iVASO subtraction approach in cortical and subcortical regions has not yet been systematically evaluated. Importantly, accurate aCBV quantification is dependent on the arterial arrival times (τ; i.e., the time for the labeled blood water to reach the capillary exchange site). Arterial arrival times, which is also frequently referred to as bolus arrival times in the arterial spin labeling literature, have been shown to be spatially dependent (19,20), with cortical times ranging from 1000–1300 ms and shorter times in subcortical structures such as the hippocampus (400–700 ms) (20). Lorentz et al. show that knowledge of arterial arrival times in different brain regions is essential for accurate aCBV measurement (21,22).

The purpose of this study was therefore, to evaluate the intra- and inter-scan reproducibility of the iVASO approach in the cortex and hippocampus. A secondary objective was to identify the TR/TI combinations (TR/TI: 500/429 ms - 5000/1191 ms, based on the T1 of arterial blood of 1627 ms (23)) that are optimal for the selected regions of interest. The results are intended to provide an exemplar of recommended imaging parameters and to outline the range of experimental error in healthy tissue.

METHODS

Healthy subjects (n = 10; mean age ± std = 22.0±2.2 years, 7M/3F) provided written informed consent for the MRI scans in compliance with the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board. These subjects were found to have no major medical, psychiatric, or neurological illness as assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID) (24). All scans were conducted on a 3T Philips Achieva MRI scanner (Best, The Netherlands) with a 32-channel receive SENSE head coil and body transmit coil. For the inter-scan session reproducibility, subjects were scanned on separate days (mean ± std inter-scan duration = 12 ± 11 days).

MRI Acquisition

A T1-weighted anatomical volume was acquired using a 3D fast field echo (FFE) sequence. Slices were oriented along the midline of the brain in the sagittal and coronal planes to minimize effects of a head tilt. The data were then re-sliced to obtain an oblique slice (spatial resolution = 1 × 1 × 4 mm3) along the long axis of both hippocampi, and the angulation information for the slice was recorded. Similarly, a slice through the superior cortical regions was selected parallel to the AC-PC line. This orientation information was used to guide the slice planning for the second scanning session. The iVASO scan comprised a single-slice, single-shot gradient echo, echo planar imaging acquisition with the following imaging parameters: nominal spatial resolution = 2.5 × 2.5 × 4 mm3, matrix size = 64 × 64, TE = 15 ms, TR = 500, 1000, 1492, 2000, 5000 ms corresponding to TI = 429, 725, 914, 1034, 1191 ms, respectively. 60 dynamics were acquired with alternating control and null images (30 each). No parallel acceleration was used. Five averages of an equilibrium magnetization (TR = 6000 ms) image with the same slice geometry but without the iVASO preparation pulses were also acquired. The inversion volume, along the slice-select direction, for non-selective inversion included the imaging slice for the null image, and was similar to Sequence IIa described in (12). However, Hua et al. applied two successive non-selective inversion pulses for the control image acquisition (12). The iVASO sequence employed in this work was similar to the one proposed by Donahue et al. (13) and used two slice selective inversion pulses for the control image as shown in Supporting Figure S1. The shim volume extended below the imaging slice to improve homogenous nulling of the incoming blood water magnetization through the intracranial segments of the carotid and basilar arteries during the non-selective inversion. For the 3T Philips Achieva scanner used in this study, the bore size was 650 mm and the length of the non-selective inversion affects task-based VASO measurements especially at short TR values. We believe that for inflow-VASO measurements of resting state aCBV inflow of fresh spin will cause an underestimation of aCBV. Extension of the shim inversion volume significantly below the imaging slice should partly mitigate this problem.

iVASO Preprocessing and Analysis

iVASO images at each TR/TI were motion corrected using a 2D correction in AFNI (2dimreg) with the first control image as the reference. aCBV was calculated using the following equation (13),

| [1] |

| [2] |

| [3] |

where ΔS is the difference signal between the control and the null image, A is a constant dependent on the scanner gain, SGM(t) is the gray matter tissue signal, M0b is the steady state magnetization of blood water, Cb is the blood water density (0.87 ml/ml) (25), TI is the inversion time, and τ is the arterial arrival time (time for inverted blood water to reach the capillary exchange site). We assumed the sequential inversion pulses were identical. i.e., Δβ was negligible because we forced the inversion pulses to be identical in shape and timing during sequence design. This assumption of Δβ =0 was also made in other studies (11,12), however the influence of this assumption on quantification is addressed in the Discussion. Under this assumption, Eq. 3 can be simplified to,

| [4] |

where E1 = 1–e(−TR/T1b), and E2 = e(−TE/R2*b) where R2*b is the R2* of blood water. The effect of the excitation pulse was accounted for in the equation for E1 (12), and it should be noted that this term was omitted by error in a prior report of this equation (13). T1b = T1 of blood water 1.627s, τ = 0.5 s for the hippocampus, and 1s for the cortex. R2* of arterial blood water = 16 s−1 and of venous blood water = 21 s−1. The product AM0b was calculated from the first control image for each TR/TI combination using a sagittal sinus region of interest (ROI) and a correction for differences between arterial and venous R2* as outlined by Petersen et al. (26). Signal in the sagittal sinus was calculated from the control image as follows:

| [5] |

| [6] |

| [7] |

Next, the left and right hippocampus were manually segmented on the high spatial resolution anatomical images for each subject. The anatomical images were skull stripped, co-registered, and down-sampled to match the matrix size of the iVASO images, and the ROIs were subsequently resampled to the iVASO image space. Mean aCBV values were recorded in the left and right hippocampus at each TI. The middle hippocampal artery, a branch of the posterior cerebral artery, partial volumes with the hippocampal ROI (27). To measure parenchymal aCBV and avoid macrovascular aCBV, voxels with aCBV > 0.05 ml/ml were excluded from the analysis. For the cortex, the anatomical images were segmented into gray and white matter for each subject using intensity based segmentation. The segmented gray matter ROI was then re-sampled into the iVASO image space. To determine whether aCBV values were affected by gray matter volumes within the selected ROIs, gray matter percentages were calculated for each ROI using FSL FAST (27).

Statistical considerations

The primary goal of our study was to assess the repeatability and reproducibility of iVASO measurements of aCBV. At each TI, intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for the left and right hippocampus as well as the cortical gray matter in the superior brain region. ICC values were calculated to assess repeatability and reproducibility of measurements, also referred to as the norm-referenced reliability (28). The ICC values were tested against a null hypothesis of ICC = 0 for each brain region at each TI. A two-tailed paired t-test was performed to determine significance (P < 0.05) for comparison of hippocampal and cortical aCBV. Furthermore, Spearman’s correlation was applied to assess the correlation between aCBV and gray matter percentages.

RESULTS

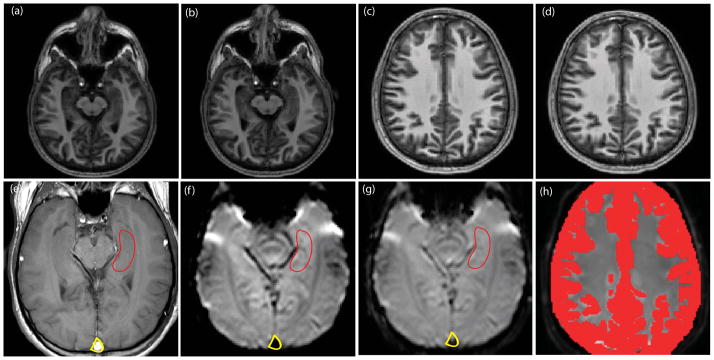

Figure 1 depicts the slice planning, hippocampal ROIs, and the cortical gray matter ROIs used for the study. The first row depicts the single slice positioning between two independent scan sessions. The second row shows the null iVASO (Figure 1f) and control iVASO (Figure 1g) images of the slice with hippocampal, sagittal sinus, and gray matter cortical (Figure 1h) ROIs. Note that the sagittal sinus signal is attributed to the blood flowing in from the superior regions into the sinus (12).

Figure 1. Slice planning and hippocampal and cortical regions of interest (ROI) for a representative subject.

The top row illustrates single slice positioning for the hippocampal formation (a) and (b) and cortex (c) and (d) at two different scanning sessions. Panel (e) illustrates the hippocampal ROI drawn on a high-resolution structural image. Null iVASO (f) and reference iVASO (g) images of the hippocampus are overlaid with the ROI draw in (e) and illustrated in (g). Panel (h) illustrates the cortical gray matter ROI overlaid with the reference cortical iVASO image.

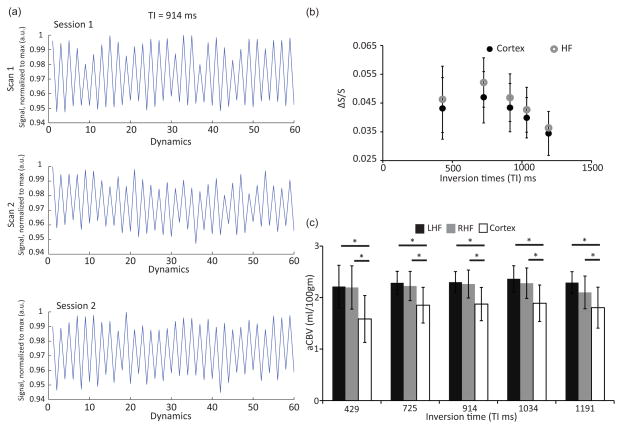

Normalized signal intensity of the sequential control and null images at a fixed TR/TI = 1492/914 ms is plotted in Figure 2. Figure 2a shows the top and middle panels of 60 dynamics for the first and second scans, respectively, within the same scanning session. The percent signal change (100*ΔS/S) was 3.17±0.81% and 2.90±0.61% for these 2 scans. The bottom panel has a percent signal change of 2.64±0.60% in a second independent scanning session for the same person at the same TR/TI. Figure 2b shows a change in signal (ΔS/S) across different TIs (429, 725, 914, 1034, and 1191 ms). ΔS/S increases from 429 ms to 725 ms and then decreases until 1191 ms in the hippocampus and cortex. In the hippocampus, the ΔS/S signal had a trend towards a higher value than in the cortex. The average aCBV values for each of these regions are shown in Figure 2c. The average aCBV value in the hippocampus was 2.21±0.42, 2.26±0.25, 2.28±0.24, 2.32±0.27, and 2.20±0.27 ml/100g at TI = 429, 725, 914, 1034, and 1191 ms, respectively. The corresponding cortical aCBV was 1.58±0.46, 1.86±0.35, 1.87±0.32, 1.89±0.35, and 1.80±0.40 ml/100g. Cortical aCBV was significantly lower than hippocampal aCBV (P < 0.05) at each TI. For the cortical ROI, gray matter volume was 77±11% while for the hippocampal ROI, it was 87±11% and were significantly different (P = 0.03). The aCBV values displayed a positive trend with gray matter percentages in the hippocampus (r = 0.35, P = 0.12) and significant positive correlation with the cortex (r = 0.61, P < 0.01) as shown in Supporting Figure S2 at an intermediate TI= 914 ms.

Figure 2.

Figure 2a. Average signal intensity in the control and null images within (scan 1 and 2 of Session 1) and between two different scanning sessions (Session 1 and Session 2) for a representative subject at a fixed TR/TI = 1492/914 ms. The top and middle panels illustrate 60 dynamic scans for the first and second scan within the same scanning session. The bottom panel shows the percent signal change during the second scanning session. The control images are denoted by odd dynamic numbers and the null images are denoted by even dynamic numbers (with open circles). Null images have lower signal intensities compared to the control image in accordance with the iVASO theory. The average percent signal changes are 3.17±0.81% (top), 2.90±0.61% (middle), and 2.64±0.60% (bottom). 2b: ΔS/S in the cortex and hippocampus at different TIs. The black and gray circles denote ΔS/S at different inversion times (429, 725, 914, 1034, 1191 ms) for the cortex and hippocampus (HF), respectively. The error bars denote standard deviation. There was no difference in ΔS/S between the hippocampus and cortex across all TIs (P = 0.36–0.65 for all TIs). The largest ΔS/S values represent compete filling of the blood compartment with labeled blood water protons. Earlier lower ΔS/S values reflect incomplete filling while the later lower ΔS/S values reflect the washout of the labeled blood water protons. 2c: Average aCBV values for the cortex and hippocampus. Lowest panel shows average arterial CBV values for the left and right hippocampus (LHF and RHF, respectively) and cortex at different inversion times. The error bars denote standard deviation. * P < 0.05. Hippocampal aCBV values were significantly higher than the cortical aCBV values at each TI.

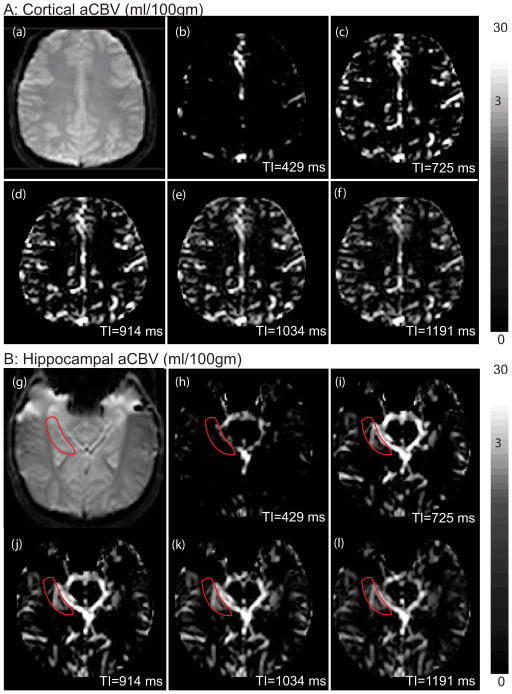

Figure 3 shows the aCBV maps at each of the five TR/TI combinations for the hippocampus and cortex. Lower signals at short TI times, Figures 3b and 3h, represent incomplete filling of the arterial compartment (i.e. before the tagged blood water reached the arteries). Similarly, reduced signals at long TI times, Figures 3f and 3l, represent wash-out (recovery of nulled blood water or replenishment by untagged fresh blood water at equilibrium) of the tagged blood water from the blood compartment. Since τ < 1.2s, exchange between labeled blood water protons and tissue water is expected to be small, thereby reducing the difference signal.

Figure 3. Arterial CBV (aCBV) maps for the cortex and hippocampus at different TR/TI.

Panel A: Cortical aCBV maps. The cortex iVASO reference image is shown in 3a, and aCBV maps are depicted from 3b–3f for the indicated TI times.

Panel B: Hippocampal aCBV maps. The hippocampal iVASO reference image in shown in 3g, and aCBV maps for the different TI times are indicated in Figures 3h–3l.

The arteries and large vessels appear bright (white) during the shortest TI, and there is almost no signal in the gray matter. Signal intensity in the large arteries increases with TI as the blood flows into the imaging slice and is followed by a decrease due to label washout.

Note the non-linear color bar to accommodate the large range of aCBV values (approximately 2.5 in parenchyma to 30 in the arteries)

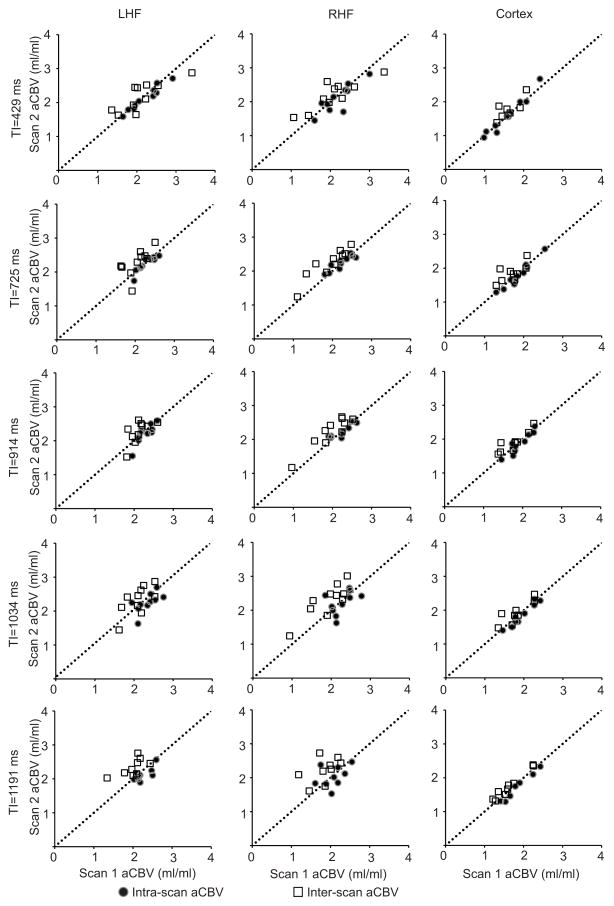

Correlation plots between intra- and inter-scan sessions for the left and right hippocampus and cortex are shown in Figure 4. The dotted line represents the line of unity i.e., correlation = 1. The filled circles represent aCBV measurement within the same scan session (intra-scan correlations), while the open squares represent aCBV measurements between two independent scan sessions (inter-scan correlations). The ICC values and the 95% confidence intervals for both intra- and inter-scan measurements in the left and right hippocampus as well as the cortical gray matter at all TR/TI times are listed in Table 1. The intra-scan ICC values ranged from 0.63–0.96 for the left hippocampus, 0.39–0.88 for the right hippocampus, and 0.93–0.97 for the cortical gray matter. The inter-scan ICC values ranged from 0.61–0.77 for the left hippocampus, 0.74–0.91 for the right hippocampus, 0.61–0.87 for the cortical gray matter. ICCs for hippocampal aCBV were highest for shorter values of TI (429, 725, and 914 ms) while the ICCs for the cortical aCBV were highest for intermediate TI values (914 and 1034 ms). Based on the descriptive statistics of our data, and assuming equal variances between two groups, with a sample size of n=10, the iVASO method has 86.5% power to significantly separate two groups (patients vs. controls, gender differences, etc.) if the aCBV difference is at least 0.41 ml blood/100g tissue.

Figure 4. Correlation plots within and between scanning sessions for the hippocampus and cortex.

Each row represents aCBV values at different TIs (429, 725, 914, 1034, and 1191 ms, respectively), while each column contains aCBV values for a brain region investigated (left column is the left hippocampal formation (LHF), middle is the right hippocampal formation (RHF), and right is the cortex). Each graph contains intra-scan (filled circles) and inter-scan (white squares) aCBV values for a certain brain region (e.g. LHF) and TI (e.g. 429 ms), with the dotted line representing the line of unity (correlation = 1).

Table 1.

Intra-class correlation values for intra- and inter-scan reproducibility of aCBV values in the left and right hippocampus and cortical gray matter. Brackets denote the 95% confidence interval for the intra-class correlation. Correlations are significant at p < 0.05 unless denoted by ⋄ (not significant).

| Left Hippocampus

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TI (ms) | Intra-scan ICC [95% CI] | Inter-scan ICC [95% CI] | ||

| 429 | 0.96 | [0.87,0.99] | 0.77 | [0.31,0.94] |

| 725 | 0.90 | [0.67,0.98] | 0.62 | [0.02,0.89] |

| 914 | 0.80 | [0.60,0.92] | 0.61 | [0.02,0.89] |

| 1034 | 0.63 | [0.15,0.89] | 0.66 | [0.14,0.90] |

| 1191 | 0.74 | [0.20,0.78] | 0.62 | [0.00,0.90] |

| Right Hippocampus

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TI (ms) | Intra-scan ICC [95% CI] | Inter-scan ICC [95% CI] | ||

| 429 | 0.85 | [0.61,0.96] | 0.79 | [0.37,0.92] |

| 725 | 0.88 | [0.59,0.95] | 0.90 | [0.64,0.97] |

| 914 | 0.86 | [0.54,0.92] | 0.91 | [0.72,0.97] |

| 1034 | 0.49 | [0.15,0.80]⋄ | 0.83 | [0.50,0.95] |

| 1191 | 0.39 | [−0.32,0.82]⋄ | 0.74 | [0.20,0.93] |

| Cortex

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TI (ms) | Intra-scan ICC [95% CI] | Inter-scan ICC [95% CI] | ||

| 429 | 0.96 | [0.87,0.99] | 0.78 | [0.16–0.95] |

| 725 | 0.97 | [0.88,0.99] | 0.69 | [0.10–0.92] |

| 914 | 0.93 | [0.73,0.98] | 0.87 | [0.55–0.97] |

| 1034 | 0.96 | [0.85,0.99] | 0.86 | [0.45–0.97] |

| 1191 | 0.96 | [0.81,0.99] | 0.61 | [0.01–0.88] |

DISCUSSION

This study illustrates that aCBV measurements can be reproduced with ICC > 0.6 in cortical gray matter and in a subcortical structure such as the hippocampus using the non-invasive iVASO approach with dynamic subtraction.

The iVASO approach may be thought of as a modified ASL technique experimentally; however, the contrast derived from blood water remains in the pre-capillary vasculature prior to exchange with tissue water. The intra- and inter-scan ICC values reported in this iVASO study are similar to those reported for ASL studies. In a study involving young adults by Xu et al., reproducibility of cerebral blood flow values ranged from 0.91–0.94 in different cortical lobes (29) while the inter-scan reproducibility ranged between 0.07–0.74 in a multi-site study by Petersen et al. (30) using the pseudo-continuous ASL approach. CBV is commonly measured using gadolinium chelates, and recent reproducibility studies indicate Pearson’s correlation of 0.73–0.84 for inter-scan CBV measurements (31,32). Our Pearson’s correlation values (0.66–0.81, data not shown) are comparable to correlation values obtained with gadolinium chelates.

Based on previous studies (12), cortical CBV (arteriolar+capillary+venous) = 5.25 ml/100g, attributing 21% to arteriolar CBV (1.10 ml/100g), 33% to capillary CBV (1.73 ml/100g), and 46% to venous CBV (2.42 ml/100g). With uncertainties in the arterial arrival times, aCBV values measured with iVASO range between 1.10 ml/100g and 2.83 ml/100g depending on the exclusion or inclusion of the capillary component of blood volume. Donahue et al. (13) and Hua et al. (11) report cortical aCBV values of 1.60±0.20 ml/100g (TR/TI = 1.78/0.98 s) and 2.04±0.27 ml/100g (when no flow-weighted gradients were used, similar to the current study) respectively. Our values of 1.58±0.46 ml/100g (lowest at TR/TI = 0.5/0.43 s) – 1.89±0.40 ml/100g (highest at TR/TI = 2/0.96 s) are within range of these studies. No hippocampal aCBV measurements have been made to date with iVASO. However, positron emission tomography measurements of total CBV have reported similar CBV values of 5.19±1.24 and 6.11±2.05 ml/100g in the right and left hippocampus respectively (33). Our hippocampal aCBV values of 2.20±0.42 ml/100g (lowest at TR/TI = 5/1.1 s) – 2.32±0.22 ml/100g (highest at TR/TI = 2/0.96 s), therefore are within the range of arteriolar+capillary CBV assuming a similar distribution of arteriolar, capillary, and venous distribution as in the cortex.

The aCBV values in the hippocampus were significantly higher in this study compared to the aCBV values in the cortical gray matter. One reason for the higher hippocampal aCBV values is the inflow of fresh spins due to a shorter τ (11,12,21,22). The hippocampus is adjacent to multiple larger arteries, including the middle hippocampal artery, which perfuses the hippocampus. This work did not incorporate flow-weighted gradients to eliminate the transient flow effects due to these arteries. We only minimized inclusion of the large cerebral arteries of the Circle of Willis near the hippocampus. Our goal was to determine repeatability and reproducibility of aCBV measurements. Second, there are significant anatomical differences in these structures. The neocortex has six layers with 70–80% excitatory pyramidal cells and 20–30% interneurons (34). In contrast, the hippocampus is an archicortical structure consisting of only three layers. Approximately 90% of all neuronal cells in the hippocampus are pyramidal neurons, and the rest are GABAergic interneurons (35). Interneurons synchronize pyramidal cell activity and generate oscillatory rhythms (e.g. theta, gamma) that are crucial for hippocampal function, especially memory (34,36). Although the ratio of interneurons to pyramidal cells is smaller in the hippocampus, they are still known to generate high-frequency gamma oscillations (36) that have high energetic demand and utilize large amounts of oxygen (37). This may result in a high baseline of metabolic activity in the hippocampus. The cortical gray matter may also have a lower metabolism than the hippocampus because the ROI included multiple brain regions (e.g. frontal, parietal) assessed at baseline activity. Third, partial volume effects between the gray matter, white matter, and CSF may further contribute to lower cortical aCBV compared to hippocampal aCBV. Inclusion of CSF and white matter in the gray matter mask is more likely to occur in cortical regions than the hippocampus, and the effects of CSF and white matter tissues need to be accounted for and may require modeling of the aCBV signal. We show that the gray matter volume in the cortical ROIs was significantly less than that in the hippocampal ROIs.

This study assumed that the consecutive inversion pulses in both the control and null images were identical i.e., Δβ = 0. We retrospectively, recalculated the aCBV values for all the subjects by evaluating and including the term with Δβ. Compared to the aCBV calculated with Δβ = 0, aCBV values were only lower by 28.06±6.22%, 6.91±6.02%, 4.43±3.30%, 5.97±4.43%, and 7.07±4.74% in the cortex at TI = 429, 725, 914, 1034, and 1191 ms respectively. These are on the order of the variation measured in the data (i.e. 13.64% of the mean aCBV value). The shortest TR/TI time showed most variation but variation in mean aCBV value for this TR/TI combination was higher at 29.11% compared to the other time-points. Similarly, hippocampal aCBV values for the five TI values were reduced by 7.26±22.7%, 3.97±8.47%, 0.32±9.6%, 5.17±4.81%, and 6.96±23.88%. aCBV value varied by 19.09% within subjects at Δβ = 0. The assumption of Δβ = 0, therefore, has a small effect on aCBV quantification.

There are some limitations to our study design. First, this method is a single slice acquisition. Novel approaches have been recently developed that utilize 3D gradient and spin echo (GRASE) readouts for rapid whole-brain acquisition within milliseconds (15,38,39). Application of flow-weighted gradients will likely significantly reduce the contributions of the transient flow and aCBV overestimation (11,22). These were not applied in our study. However, large arteries perfusing the hippocampus are in the plane of the hippocampal slice and hence flow-weighted gradients likely need to be applied in multiple directions for efficient nulling, which will add considerably to TE and corresponding BOLD effects. Alternatively, modeling of inflowing blood water spins can be pursued in the future to correct aCBV values using multiple TR/TI times.

Modeling and fitting procedures for multiple TR/TI times allow determination of multiple parameters including, aCBV, cerebral blood flow, τ. Utilizing just five time points for these three parameters did not provide a robust fit in this study. Future studies could include acquisitions at more TR/TI times. Exchange of blood water protons with the tissue can additionally cause aCBV overestimation. However, it has been shown that exchange effects are negligible and do not affect aCBV values (Figure 3b, (11)) for all physiological TIs, especially ≤ 1000 ms. Exchange effects are more relevant in arterial spin labeling studies where label duration ~ 1s and post-labeling delays are >1.5s.

Multi-post-labeling delay ASL has been used successfully to obtain simultaneous measurements of whole brain cerebral blood flow, arterial blood volume, and arterial transit time (40). While this ASL method assesses several hemodynamic parameters compared to iVASO, there are some notable limitations. The arterial transit time is limited by the selected range of post-labeling delays (41), which may be influenced by neurological disease conditions and medications. In addition, there is a trade-off between scan time and signal to noise ratio in ASL. In order to have a feasible scan time with multiple, long (2–3 s) post-labeling delays, fewer control and label pairs are collected (40), resulting in lower signal to noise ratio than the iVASO method. This is because typical pseudo-continuous ASL sequences are insensitive to τ. Accurate measurement of τ needs pulsed ASL sequences, which suffer from poor spin tagging and hence low signal to noise ratio.

Finally, the spatial resolution for ASL is lower compared to the resolution in iVASO, making it difficult to assess hemodynamics in small, subcortical brain structures. Current nominal spatial resolution of iVASO makes it difficult to resolve aCBV at the level of hippocampal subfields. This will be necessary in order to test current hypotheses of hippocampal dysfunction in neuropsychiatric disorders (42). Furthermore, magnetization transfer pulses can be used to increase signal-to-noise ratio of VASO images or to reduce acquisition time (43). Expansion to whole brain coverage with corrections for partial volume effects with CSF and white matter will greatly improve the applicability of the iVASO approach.

CONCLUSION

This study investigates the intra- and inter-scan reproducibility of the non-invasive iVASO approach to measure arterial cerebral blood volume. The intra-class correlation coefficients for iVASO are similar to that of arterial spin labeling approaches. aCBV values measured with iVASO are dependent on the arterial arrival times of the regions in which they are being measured. This work shows that hippocampal aCBV values have higher reproducibility at TI < 1000 ms while cortical aCBV values have higher reproducibility at TIs between 725 ms and 1034 ms.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Figure S1: iVASO pulse sequence diagram. Control image is acquired by two consecutive slice-selective inversion pulses, while null image is acquired by a non-selective inversion pulse followed by a slice selective inversion pulse.

Supporting Figure S2: aCBV relationship with gray matter percentage in the manually segmented hippocampus (open squares, r = 0.35, P = 0.12) and in the automated cortical segmentation (closed circles, r = 0.61, P < 0.01).

Acknowledgments

Funding: Vanderbilt Office of Clinical and Translational Scientist Development (SR), F30 MH102846 (PT), T32 GM07347 (PT), R01 MH070560 (SH), NIH/NINDS 5R01NS078828-03 (MJD), American Heart Association 14GRNT20150004

References

- 1.Khan UA, Liu L, Provenzano FA, Berman DE, Profaci CP, Sloan R, Mayeux R, Duff KE, Small SA. Molecular drivers and cortical spread of lateral entorhinal cortex dysfunction in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(2):304–311. doi: 10.1038/nn.3606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schobel SA, Lewandowski NM, Corcoran CM, Moore H, Brown T, Malaspina D, Small SA. Differential targeting of the CA1 subfield of the hippocampal formation by schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(9):938–946. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leenders KL, Perani D, Lammertsma AA, Heather JD, Buckingham P, Healy MJ, Gibbs JM, Wise RJ, Hatazawa J, Herold S, et al. Cerebral blood flow, blood volume and oxygen utilization. Normal values and effect of age. Brain. 1990;113 (Pt 1):27–47. doi: 10.1093/brain/113.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brambilla P, Cerini R, Fabene PF, Andreone N, Rambaldelli G, Farace P, Versace A, Perlini C, Pelizza L, Gasparini A, Gatti R, Bellani M, Dusi N, Barbui C, Nose M, Tournikioti K, Sbarbati A, Tansella M. Assessment of cerebral blood volume in schizophrenia: A magnetic resonance imaging study. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2007;41(6):502–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moreno H, Hua F, Brown T, Small S. Longitudinal mapping of mouse cerebral blood volume with MRI. NMR Biomed. 2006;19(5):535–543. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pechman KR, Donohoe DL, Bedekar DP, Kurpad SN, Hoffmann RG, Schmainda KM. Characterization of bevacizumab dose response relationship in U87 brain tumors using magnetic resonance imaging measures of enhancing tumor volume and relative cerebral blood volume. J Neurooncol. 2011;105(2):233–239. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0591-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mintun MA, Raichle ME, Martin WR, Herscovitch P. Brain oxygen utilization measured with O-15 radiotracers and positron emission tomography. J Nucl Med. 1984;25(2):177–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuppusamy K, Lin W, Cizek GR, Haacke EM. In vivo regional cerebral blood volume: quantitative assessment with 3D T1-weighted pre- and postcontrast MR imaging. Radiology. 1996;201(1):106–112. doi: 10.1148/radiology.201.1.8816529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rempp KA, Brix G, Wenz F, Becker CR, Guckel F, Lorenz WJ. Quantification of regional cerebral blood flow and volume with dynamic susceptibility contrast-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology. 1994;193(3):637–641. doi: 10.1148/radiology.193.3.7972800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin W, Celik A, Paczynski RP. Regional cerebral blood volume: a comparison of the dynamic imaging and the steady state methods. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;9(1):44–52. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199901)9:1<44::aid-jmri6>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hua J, Qin Q, Pekar JJ, van Zijl PC. Measurement of absolute arterial cerebral blood volume in human brain without using a contrast agent. NMR Biomed. 2011;24(10):1313–1325. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hua J, Qin Q, Donahue MJ, Zhou J, Pekar JJ, van Zijl PC. Inflow-based vascular-space-occupancy (iVASO) MRI. Magnetic resonance in medicine: official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine/Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2011;66(1):40–56. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donahue MJ, Sideso E, MacIntosh BJ, Kennedy J, Handa A, Jezzard P. Absolute arterial cerebral blood volume quantification using inflow vascular-space-occupancy with dynamic subtraction magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism: official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2010;30(7):1329–1342. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu H, Golay X, Pekar JJ, Van Zijl PC. Functional magnetic resonance imaging based on changes in vascular space occupancy. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50(2):263–274. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poser BA, Norris DG. 3D single-shot VASO using a Maxwell gradient compensated GRASE sequence. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62(1):255–262. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grohn OH, Lukkarinen JA, Oja JM, van Zijl PC, Ulatowski JA, Traystman RJ, Kauppinen RA. Noninvasive detection of cerebral hypoperfusion and reversible ischemia from reductions in the magnetic resonance imaging relaxation time, T2. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18(8):911–920. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199808000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hillman EM, Devor A, Bouchard MB, Dunn AK, Krauss GW, Skoch J, Bacskai BJ, Dale AM, Boas DA. Depth-resolved optical imaging and microscopy of vascular compartment dynamics during somatosensory stimulation. Neuroimage. 2007;35(1):89–104. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mezue M, Segerdahl AR, Okell TW, Chappell MA, Kelly ME, Tracey I. Optimization and reliability of multiple postlabeling delay pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling during rest and stimulus-induced functional task activation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34(12):1919–1927. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J, Alsop DC, Song HK, Maldjian JA, Tang K, Salvucci AE, Detre JA. Arterial transit time imaging with flow encoding arterial spin tagging (FEAST) Magn Reson Med. 2003;50(3):599–607. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li X, Sarkar SN, Purdy DE, Spence JS, Haley RW, Briggs RW. Anteroposterior perfusion heterogeneity in human hippocampus measured by arterial spin labeling MRI. NMR Biomed. 2013;26(6):613–621. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lorenz K, Mildner T, Pampel A, Möller HE. Flow-weighted iVASO-DS for absolute arterial CBV quantification. Montreal, QC, Canada: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lorenz K, Mildner T, Pampel A, Möller HE. Transient effects in arterial CBV Quantification. Salt Lake City, UT, USA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu H, Clingman C, Golay X, van Zijl PC. Determining the longitudinal relaxation time (T1) of blood at 3. 0 Tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52(3):679–682. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.First MB, Spitzer Robert L, Miriam Gibbon, Williams Janet BW, editors. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition With Psychotic Screen (SCID-I/P W/PSY SCREEN) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; Nov, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herscovitch P, Raichle ME. What is the correct value for the brain--blood partition coefficient for water? J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1985;5(1):65–69. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1985.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petersen ET, Lim T, Golay X. Model-free arterial spin labeling quantification approach for perfusion MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55(2):219–232. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duvernoy HM, Cattin Françoise, Risold Pierre-Yves. The human hippocampus: functional anatomy, vascularization and serial sections with MRI. Springer; 2013. p. 237. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGraw KO, Wong SP. Forming inferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychol Methods. 1996;1(1):30–46. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu G, Rowley HA, Wu G, Alsop DC, Shankaranarayanan A, Dowling M, Christian BT, Oakes TR, Johnson SC. Reliability and precision of pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling perfusion MRI on 3. 0 T and comparison with 15O-water PET in elderly subjects at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. NMR Biomed. 2010;23(3):286–293. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petersen ET, Mouridsen K, Golay X. The QUASAR reproducibility study, Part II: Results from a multi-center Arterial Spin Labeling test-retest study. Neuroimage. 2010;49(1):104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.07.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henry ME, Kaufman MJ, Lange N, Schmidt ME, Purcell S, Cote J, Perron-Henry DM, Stoddard E, Cohen BM, Renshaw PF. Test-retest reliability of DSC MRI CBV mapping in healthy volunteers. Neuroreport. 2001;12(8):1567–1569. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200106130-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shin W, Horowitz S, Ragin A, Chen Y, Walker M, Carroll TJ. Quantitative cerebral perfusion using dynamic susceptibility contrast MRI: evaluation of reproducibility and age- and gender-dependence with fully automatic image postprocessing algorithm. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58(6):1232–1241. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ishii K, Sasaki M, Yamaji S, Sakamoto S, Kitagaki H, Mori E. Paradoxical hippocampus perfusion in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. J Nucl Med. 1998;39(2):293–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Markram H, Toledo-Rodriguez M, Wang Y, Gupta A, Silberberg G, Wu C. Interneurons of the neocortical inhibitory system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5(10):793–807. doi: 10.1038/nrn1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heckers S, Konradi C. Hippocampal pathology in schizophrenia. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. 2010;4:529–553. doi: 10.1007/7854_2010_43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cobb SR, Buhl EH, Halasy K, Paulsen O, Somogyi P. Synchronization of neuronal activity in hippocampus by individual GABAergic interneurons. Nature. 1995;378(6552):75–78. doi: 10.1038/378075a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kann O, Huchzermeyer C, Kovacs R, Wirtz S, Schuelke M. Gamma oscillations in the hippocampus require high complex I gene expression and strong functional performance of mitochondria. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 2):345–358. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Donahue MJ, Blicher JU, Ostergaard L, Feinberg DA, MacIntosh BJ, Miller KL, Gunther M, Jezzard P. Cerebral blood flow, blood volume, and oxygen metabolism dynamics in human visual and motor cortex as measured by whole-brain multi-modal magnetic resonance imaging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29(11):1856–1866. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huber L, Ivanov D, Krieger SN, Streicher MN, Mildner T, Poser BA, Moller HE, Turner R. Slab-selective, BOLD-corrected VASO at 7 Tesla provides measures of cerebral blood volume reactivity with high signal-to-noise ratio. Magn Reson Med. 2014;72(1):137–148. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang DJ, Alger JR, Qiao JX, Gunther M, Pope WB, Saver JL, Salamon N, Liebeskind DS. Multi-delay multi-parametric arterial spin-labeled perfusion MRI in acute ischemic stroke - Comparison with dynamic susceptibility contrast enhanced perfusion imaging. Neuroimage Clin. 2013;3:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang R, Yu S, Alger JR, Zuo Z, Chen J, An J, Wang B, Zhao J, Xue R, Wang DJ. Multi-delay arterial spin labeling perfusion MRI in moyamoya disease--comparison with CT perfusion imaging. Eur Radiol. 2014;24(5):1135–1144. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3098-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Small SA, Schobel SA, Buxton RB, Witter MP, Barnes CA. A pathophysiological framework of hippocampal dysfunction in ageing and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12(10):585–601. doi: 10.1038/nrn3085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hua J, Donahue MJ, Zhao JM, Grgac K, Huang AJ, Zhou J, van Zijl PC. Magnetization transfer enhanced vascular-space-occupancy (MT-VASO) functional MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61(4):944–951. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Figure S1: iVASO pulse sequence diagram. Control image is acquired by two consecutive slice-selective inversion pulses, while null image is acquired by a non-selective inversion pulse followed by a slice selective inversion pulse.

Supporting Figure S2: aCBV relationship with gray matter percentage in the manually segmented hippocampus (open squares, r = 0.35, P = 0.12) and in the automated cortical segmentation (closed circles, r = 0.61, P < 0.01).