Abstract

In New York City, federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) are ideal partners for health departments because of their location in neighborhoods with high rates of HIV, hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, and gonorrhea. Providers have experienced many barriers to following screening and treatment recommendations. In 2013, the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene partnered with six FQHCs, representing 14 clinics, to make screening for HIV and HCV routine and increase adherence to gonorrhea treatment guidelines through education, electronic health record modification, and progress tracking. After one year, 12 of 14 clinics documented improvement in their HIV offer rate, and 11 clinics documented improvement in their HIV screening rate. Patients who were offered HIV screening increased from 26% at baseline to 56% at follow-up, and patients screened for HIV increased from 25% at baseline to 38% at follow-up. Most clinics improved their HIV screening rate, and progress suggests that local health departments can help FQHCs increase their HIV screening rates.

Federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) in New York City are located in neighborhoods with high rates of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs).1–3 FQHCs are community-based, nonprofit health centers with a mission to provide comprehensive primary care services to medically underserved areas or populations. In addition, many FQHCs have implemented electronic health records (EHRs), which can identify patients who need screening or treatment and provide data about services provided. FQHCs make ideal partners for health departments to assure screening for HIV, HCV infection, and STIs because of their missions, patient populations, locations, and services provided.

New York City has one of the oldest and largest HIV epidemics in the United States. At the end of 2012, an estimated 144,635 people infected with HIV lived in New York City, with 14% of those infected remaining undiagnosed.4 Activities that place people at risk for acquiring HIV also place them at risk for HCV infection and other STIs. Among people reported with HIV in New York City from 2000 to 2010, 16% were also reported as having HCV infection, and 6% were reported as having gonorrhea.5

Routine screening of patients for HIV, HCV infection, and STIs by primary care providers is critical for prevention, treatment, and care efforts.6–8 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommend routine HIV screening for adolescents and adults,9,10 and at least one hepatitis C screening for adults born between 1945 and 1965, or baby boomers.11,12 In 2010, New York State passed a law mandating that individuals aged 13–64 years receive an offer for HIV testing in primary care and other health-care settings.13 In 2014, the state also passed a law mandating that adults born between 1945 and 1965 receive an offer for one-time screening for HCV in primary care and other health-care settings.14 Treatment for gonorrhea infection is challenging due to the propensity of gonorrhea to develop resistance to antibiotics. Inadequate treatment enables the spread of antibiotic-resistant gonorrhea. In 2012, CDC released new treatment guidelines specifying ceftriaxone and azithromycin as the only recommended treatment for gonorrhea.15

Primary care providers have experienced many barriers to implementing routine HIV screening.16,17 To assist primary care providers, the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) partnered with local FQHCs to make HIV and HCV screening routine and increase adherence to current gonorrhea treatment guidelines through modification of EHRs. We describe key steps that other health departments can replicate to partner with community health centers, our challenges, and lessons learned. We specifically focus on the partnership's first year and the outcomes of HIV-related activities.

METHODS

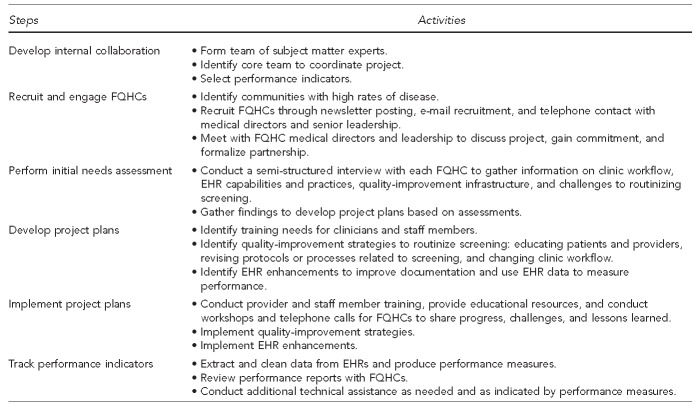

The partnership project included six key steps (Figure 1). First, building on CDC's program collaboration and service integration framework,18 we brought together staff members from DOHMH programs responsible for HIV, HCV infection, and STIs to develop a project team. Next, we targeted a subset of FQHC partners by identifying ZIP Codes with high rates of HIV, HCV infection, and gonorrhea. We identified 23 FQHCs, 16 of which were eligible to participate.19 FQHCs located in the ZIP Codes with high rates of disease and that used an EHR—and could add fields, make modifications to templates, and were able to pull data and create reports—were considered eligible.

Figure 1.

Key steps in a health department/community health center partnership to increase screening for HIV, hepatitis C, and gonorrhea treatment adherence, New York City, 2013–2014

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

FQHC = federally qualified health center

EHR = electronic health record

To solicit participation from FQHCs, we publicized project information through the New York State membership association of FQHCs and contacted medical directors and senior leadership by phone and e-mail. We met with FQHC medical directors and leadership to generate commitment and formalize a partnership in early 2013. Six FQHC networks representing 14 clinics joined the project and received limited funding for participating.

We conducted semi-structured interviews with each participating FQHC network to gather information on clinic workflow, EHR capabilities and practices, quality-improvement infrastructure, and challenges to routinizing screening. We used the findings to develop project plans that included three components: (1) training and technical assistance to educate providers and staff members, (2) quality-improvement strategies to routinize screening, and (3) EHR enhancements to improve documentation and utilize EHR data to measure performance. Each FQHC identified a project champion and established a team of clinical and informatics staff members. Buy-in within FQHCs was gained through senior-level support and dissemination of project activities and goals.

Provider and staff education

To address training needs, we provided a list of grand rounds for medical providers and staff members on a wide range of topics related to HIV, HCV infection, and gonorrhea. From spring 2013 through summer 2014, DOHMH conducted 19 on-site training sessions and provided educational resources for more than 300 FQHC providers and staff members. FQHCs had opportunities to share progress, challenges, and best practices directly with each other through three in-person workshops in July 2013, February 2014, and August 2014, and three group conference calls in June, August, and November 2013.

Routinizing screening

FQHCs implemented many quality-improvement strategies, including educating patients and providers, revising protocols or processes related to screening, and changing clinic workflow. All FQHCs posted information on HIV testing, including DOHMH “Say Yes to the Test” posters, which were hung in clinic waiting rooms and examination rooms to address providers' unease with offering HIV testing and encourage patients to request testing. Four FQHCs redistributed responsibilities among staff members to better integrate routine HIV screening into the medical visit. Redistributing responsibilities included expanded responsibilities for nurses, medical assistants, registration staff members, and care team members, and an effort to move away from the HIV testing counselor model.

EHR enhancements

Five FQHCs enhanced their EHRs to better document HIV information (e.g., the offer of a test) and streamline screening, including adding structured fields and reorganizing existing fields. Three FQHCs added EHR prompts to remind staff members to offer screening, including alerts prompted by patient demographics and auto-populated fields based on patient data.

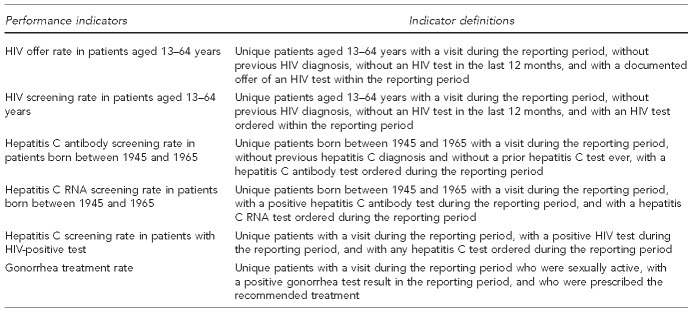

EHR data were used to measure performance. FQHCs extracted and cleaned EHR data for each clinic four times during the project time period and produced an analyzable dataset. All FQHCs improved their ability to extract and clean EHR data and, using the dataset, we produced several performance measures (Figure 2). For this analysis, data from April through June 2013 served as the baseline, and data from April through June 2014 served as the follow-up. FQHCs reported unique patients per month, and the number of patients was averaged during the three-month period for each clinic and for each FQHC entity.

Figure 2.

Performance measures used in a health department/community health center partnership to measure change in screening for HIV, hepatitis C, and gonorrhea treatment adherence, New York City, 2013–2014

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

RNA = ribonucleic acid

OUTCOMES

After one year, among the 14 clinics, 12 documented improvement in their HIV offer rates and 11 documented improvement in their HIV screening rates. We calculated and compared screening rates at the clinic level. On average, the percentage of patients who were offered HIV screening increased from 26% at baseline to 56% at follow-up. On average, the FQHC screening rates for HIV increased from 25% at baseline to 38% at follow-up. According to FQHC staff members, the modest increase in screening rates may have been due to patient perceptions that they were not at risk or that they were recently screened at another facility. In total, FQHCs identified 70 patients who were previously undiagnosed at their clinics, although it is unknown if these patients were previously diagnosed at another facility. We reviewed performance reports with current performance, performance over time, and recommendations with FQHC teams every three months through in-person meetings. We revised project plans and identified technical assistance based on performance measures.

LESSONS LEARNED

Most clinics improved their HIV screening rate in the first year. Progress suggests that ongoing relationships between health departments and community health centers can increase HIV, hepatitis C, and gonorrhea screening rates and strengthen public health and primary care integration. Because of differences in EHR use, patient populations, and services offered, each clinic required different strategies for sustainable improvement. DOHMH worked with each FQHC to develop site-specific project plans. Successful implementation of quality-improvement strategies was an iterative process that required substantial follow-up and sustained relationships with FQHC teams. FQHC teams implemented changes in a limited way and assessed the impact before implementing successful changes to the full clinic. DOHMH worked with FQHCs to assess the impact, roll out successful strategies to the full clinic, and maintain the timeline in their project plans.

EHRs provide many benefits to community health centers, but they also pose challenges as quality-improvement tools. At the start of the project, several FQHCs were not documenting the offer of an HIV test in a structured field, and most FQHCs had not streamlined their EHR fields. Data extraction and analysis were limited at several FQHCs due to staff member capacity and EHR or reporting software limitations. Using EHR data to produce performance measures was a challenge, as performance measures can be difficult to define.20 Many elements, such as visit type, time period, and patient eligibility, must be defined to develop performance measures. FQHCs extracted aggregate data reflecting services provided by month, which allowed us to see the seasonality in performance measures, identify changes over time at the clinic level, and compare improvement across clinics.

FQHCs with an existing quality-improvement infrastructure were better positioned to make screening routine. Education on screening guidelines and EHR changes alone were insufficient to change provider behavior. Ongoing communication of project goals among all FQHC staff members and providing performance feedback to FQHCs were both essential to driving quality-improvement. FQHCs that had a limited quality-improvement infrastructure were less familiar with their EHR data and required several data extractions before they felt confident that the data were accurate. They also required more time to examine and implement quality-improvement strategies. FQHCs with an existing quality-improvement infrastructure were more familiar with their data and with quality-improvement strategies that would be successful at their site. Several FQHCs were concurrently participating in other quality-improvement initiatives on a range of health topics, including diabetes, cardiovascular health, and obesity. Clinics were limited by the amount of staff time and EHR-related changes they could introduce or commit to projects focused on improving screening for sexual health. For this reason, packaging quality-improvement initiatives together rather than focusing on a single disease is one way to maximize the impact of the quality-improvement initiatives.

Limitations

This study was subject to several limitations regarding the use of aggregate EHR data. These data may have overestimated the patient population, as patients could be included in multiple months of data. In addition, aggregate data did not identify the performance of specific providers. In the second project year, we will focus on provider-level data to better identify providers who may need assistance to improve screening.

CONCLUSION

The project's initial results suggest that health department partnerships with community health centers play an important role in improving screening for infectious diseases. Although primary care and public health are typically isolated from each other, improvements in population health and health-care efficiency can be achieved through greater collaboration.21 Limitations in the design, implementation, and use of EHRs must be overcome to increase health-care quality.22,23 EHRs require additional customization, and staff members often require additional assistance to utilize EHRs for quality-improvement and public health. A longer period of engagement and higher levels of technical assistance may be necessary for public health agencies to help primary care practices realize quality-improvement from EHRs.24 The key elements of partnering with providers that serve neighborhoods with high rates of infectious disease, providing a range of technical assistance, and measuring progress through EHR data can be replicated by local health departments focused on infectious diseases or other health conditions.

Footnotes

The authors thank community health center staff members for participating in the partnership; Sam Amifar, Sheila Anane, Blayne Cutler, and Laura Jacobson for input on the project design; and Molly Kratz for comments on previous versions of the manuscript.

This project did not include human subjects research and was not under the purview of the institutional review board. A Gilead Sciences Frontlines of Communities in the United States grant supported this project.

REFERENCES

- 1.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. HIV surveillance annual report, 2012 [cited 2014 Sep 10] Available from: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/dires/surveillance-report-dec-2013.pdf.

- 2.Ackelsberg J, Laraque F, Bornschlegel K, Rude E, Varma J. New York: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Viral Hepatitis Surveillance, Prevention and Control Program; 2013. Hepatitis C in New York City: state of the epidemic and action plan. Also available from: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/cd/hepC-action-plan.pdf [cited 2014 Sep 10] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Summers C, Cohen L, Havusha A, Sliger F, Farley T. New York: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2009. Take care New York 2012: a policy for a healthier New York City. Also available from: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/tcny/tcny-2012.pdf [cited 2014 Sep 10] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eavey JJ, Torian LV, Jablonsky A, Nickerson JE, Fettig JF, Leider J, et al. Undiagnosed HIV infection in a New York City emergency room: results of a blinded serosurvey, December 2009–January 2010. Presented at the 19th International AIDS Conference; 2012 Jul 22–27; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drobnik A, Pinchoff J, Bushnell G, Terranova E, Fuld J. New York: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene: Epi Research Report; 2013. Matching New York City viral hepatitis, tuberculosis, sexually transmitted diseases and HIV surveillance data, 2000–2010. Also available from: https://www1.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/epi/epiresearch-pcsi.pdf [cited 2014 Sep 10] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fenton KA. Changing epidemiology of HIV/AIDS in the United States: implications for enhancing and promoting HIV testing strategies. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(Suppl 4):S213–20. doi: 10.1086/522615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donnell D, Baeten JM, Kiairie J, Thomas KK, Stevens W, Cohen CR, et al. Heterosexual HIV-1 transmission after initiation of antiretroviral therapy: a prospective cohort analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:2092–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60705-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marks G, Crepaz N, Senterfitt JW, Janssen RS. Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States: implications for HIV prevention programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:446–53. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000151079.33935.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, Janssen RS, Taylor AW, Lyss SB, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Preventive Services Task Force (US) Rockville (MD): USPSTF; 2013. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection: screening. Also available from: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspshivi.htm [cited 2014 Sep 10] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett BA, Flack-Ytter Y, Holtzman D, Teo CG, et al. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945–1965. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;61(RR-4):1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Preventive Services Task Force (US) Rockville (MD): USPSTF; 2013. Hepatitis C: screening. Also available from: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspshepc.htm [cited 2014 Sep 10] [Google Scholar]

- 13. N.Y. Public Health Law §2786 (2010)

- 14. N.Y. Public Health Law §2171 (2014)

- 15.del Rio C, Hall G, Holmes K, Soge O, Hook E, Kirkcaldy R, et al. Update to CDC's sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010: oral cephalosporins no longer a recommended treatment for gonococcal infections. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(31):590–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klein PW, Messer LC, Myers ER, Weber DJ, Leone PA, Miller WC. Impact of a routine, opt-out HIV testing program on HIV testing and case detection in North Carolina sexually transmitted disease clinics. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41:395–402. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korthuis PT, Berkenblit GV, Sullivan LE, Cofrancesco J, Jr, Cook RL, Bass M, et al. General internists' beliefs, behaviors, and perceived barriers to routine HIV screening in primary care. AIDS Educ Prev. 2011;23(Suppl 3):70–83. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.3_supp.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Atlanta: CDC; 2009. Program collaboration and service integration: enhancing the prevention and control of HIV/AIDS, viral hepatitis, sexually transmitted diseases, and tuberculosis in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Department of Health and Human Services (US), Health Research and Services Administration. HRSA data warehouse: health care service delivery and look-alike sites data download [cited 2014 Sep 10] Available from: http://datawarehouse.hrsa.gov/data/datadownload/hccdownload.aspx.

- 20.Tang PC, Ralston M, Arrigotti MF, Qureshi L, Graham J. Comparison of methodologies for calculating quality measures based on administrative data versus clinical data from an electronic health record system: implications for performance measures. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;14:10–5. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Research Council. Washington: National Academies Press; 2012. Primary care and public health: exploring integration to improve population health. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baron RJ. Quality-improvement with an electronic health record: achievable, but not automatic. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:549–52. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kellermann AL, Jones SS. What it will take to achieve the as-yet-unfulfilled promises of health information technology? Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:63–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryan AM, Bishop TF, Shih S, Casalino LP. Small physician practices in New York needed sustained help to realize gains in quality from use of electronic health records. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:53–62. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]