Abstract

Objective

One in seven of the 1.1 million people living in the United States infected with HIV are not aware of their HIV status. At the same time, many clinical settings have not adopted routine HIV screening, which promotes linkage to specialist medical care. We sought to improve HIV screening in a large community health center network by using a data-driven, collaborative learning approach and system-wide modifications, where counselor-based HIV screening and testing were replaced by health-care providers and medical assistants.

Methods

Urban Health Plan, Inc., a network of federally qualified health centers in the boroughs of the Bronx and Queens in New York City, provided HIV screening training for its health-care providers. In January 2011, it modified its electronic medical record system to incorporate HIV test offering. This study compared the 2010 baseline year with the three-year implementation follow-up period (January 2011 through December 2013) to determine the number of eligible individuals for HIV testing, HIV tests offered and performed, HIV-positive individuals, and HIV cases linked to specialty care.

Results

A total of 26,853 individuals at baseline and 100,369 individuals in the implementation period were eligible for HIV testing. HIV testing was performed on 2,079 (8%) of 26,853 eligible individuals in 2010 and 49,646 (50%) of 100,369 eligible individuals from 2011 through 2013. HIV-positive status was determined in 19 (0.9%) of 2,079 tested individuals in 2010 and 166 (0.3%) of 49,646 tested individuals from 2011 through 2013. Linkage to care was observed in all 19 eligible individuals and 127 (77%) of 166 eligible individuals who tested HIV positive in 2010 and 2011–2013, respectively.

Conclusion

This study enabled routine HIV implementation testing at a community health center network, which resulted in enhanced HIV testing, an increased number of HIV-positive cases identified, and a rise in the number of patients linked to HIV specialist care.

The number of individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is increasing in the United States despite new testing guidelines, effective HIV prevention strategies, and advances in HIV treatment. An estimated 1.1 million people in the United States are living with HIV, and an additional 47,500 individuals become infected with HIV each year.1,2 It is further estimated that more than 168,300 people are not yet diagnosed.1 Undiagnosed infection remains a significant factor fueling the current HIV epidemic in the United States.3

More than half of adults have not yet been tested for HIV.3 Fear and misperceptions keep people from finding out their HIV status. Many people, even those who engage in high-risk behavior, do not get tested because they do not believe they are at risk for HIV, while others misunderstand the testing process. Many individuals are also concerned that others may find out about their positive status, while others avoid HIV testing because they fear a positive test result.4–8

According to the New York City (NYC) Department of Health and Mental Hygiene's 2013 HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) report, there were 2,832 new HIV cases (including 1,784 AIDS cases) and 117,618 people living with HIV/AIDS in NYC in 2013. Additionally, 1,527 deaths (for any cause) were reported among HIV-positive individuals in NYC in 2013.9

Urban Health Plan (UHP), Inc. is a network of federally qualified health centers located in the Bronx and Queens boroughs of NYC. UHP initiated an internal collaborative learning initiative on January 1, 2011. The intent of the collaborative learning project was to train all primary care and gynecologic providers to routinely offer HIV testing to patients aged 13–64 years throughout the UHP network of health centers and school-based health clinics.

A preliminary, very brief report from Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report regarding the novel HIV screening program at UHP demonstrated successful HIV screening implementation through electronic medical record (EMR) modification, staff education, and a shift from point-of-care, rapid testing to laboratory testing. The UHP HIV screening program is based on four principles: (1) institutional policy change reflecting an organization-wide commitment to routine HIV testing and diagnosis; (2) integration of HIV testing into existing clinical workflows to promote its normalization and sustainability; (3) use of EMRs to prompt testing, automate laboratory orders, and track performance; and (4) required staff education on HIV testing best practices and outcomes. These four principles have allowed routine integration of HIV screening into UHP's clinical workflow, scalability, and sustainability.10

The present study expanded on the UHP collaborative learning methods that enabled routine HIV screening implementation across the UHP network of health centers by providing the number of HIV tests conducted, HIV-positive cases identified, and patients linked to specialty HIV care among individuals eligible and offered routine HIV screening at UHP for the 2010 baseline year and the 2011–2013 implementation follow-up period.

METHODS

Data presented in this study were from January 1, 2010, through December 31, 2013. Implementation of the collaborative learning project at UHP occurred from January 1, 2011, onward. The UHP collaborative project started with five health practice sites in 2011; it expanded in 2013 to nine community practice sites (eight in the Bronx and one in Queens) and eight school-based health clinics. The UHP community health practice sites included the Plaza Del Sol Health Center in Queens, and the El Nuevo San Juan Health Center, Plaza Del Castillo Health Center, Bella Vista Health Center, Kips Bay Boys and Girls Club, Bella Vista Community Health Center, Adolescent Health & Wellness Center, Peninsula Community Health Center, and St. Lawrence Community Health Center in the Bronx.

UHP serves a unique community in the South Bronx whose residents suffer from substantial economic challenges and racial/ethnic health disparities. The Bronx is one of the poorest congressional districts in the country: It ranks among the highest 2% of U.S. counties in poverty and has an unemployment rate that is among the highest 1% of U.S. counties.11 Most residents in the UHP's Bronx coverage area also only speak Spanish and, as such, are linguistically isolated.

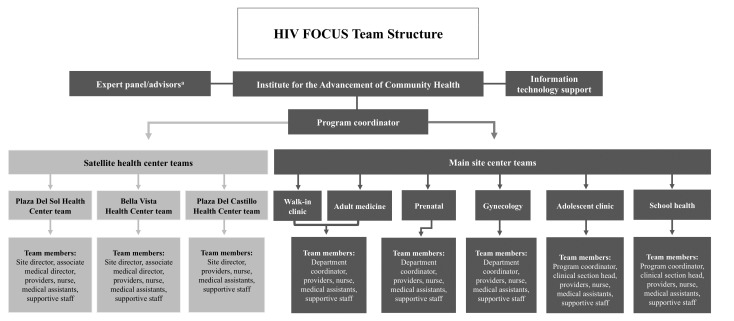

Three evidence-based models to improve quality of care and health outcomes were the framework for the original implementation of the multisite collaborative learning project for enhanced HIV testing at UHP: the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Learning Model,12 Ed Wagner's Chronic Care Model,13 and the Model for Improvement (Plan, Do, Study, Act Cycle).14 The post-2010 UHP multisite collaborative learning HIV screening project was structured so that each practice site formed its own discrete performance improvement team with a designated health-care provider champion led by internal quality-improvement staff members (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

HIV FOCUS program collaborative learning team structure applied across Urban Health Plan, Inc., clinics in the Bronx and Queens, New York, from 2011 onward

aIncludes senior leaders, clinical system administrator, director of nursing, clinical director of HIV, services/infectious disease specialist, and others as determined.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

FOCUS = Frontlines of Communities in the United States

From January to September 2011, two separate, one-hour HIV screening implementation education sessions were provided to selected health-care provider champions and their medical assistants who had clinical supervisory responsibility at their respective practice sites. A training toolkit was provided with topics that included the New York State HIV testing law, performance improvement models, a new workflow, and EMR modifications. Representatives from UHP senior leadership were present at the education sessions to demonstrate support for the learning collaborative.

The purpose of these sessions was to share challenges, successes, and best practices among the teams. Each team comprised, at a minimum, a provider champion and a medical assistant, and each team member had a defined role in the process. Quality improvement staff members developed an interactive team-training curriculum and included a project-specific change package, which described the teams' action plan. The provider champion tested the new process with his or her patients using a medical assistant for support. As the process was successfully tested, other providers and their medical assistants were trained until all staff members involved were able to implement the new testing process. In total, 25 physicians, 16 physician assistants, eight nurse practitioners, and eight gynecologists and obstetric providers (and their medical assistants) participated in UHP's collaborative learning project during the 2011–2013 period.

The workflow and EMR at UHP were modified so that the health-care providers and medical assistants would change their current practices and offer HIV testing as part of routine care rather than relying on counselors. As an enhancement to the EMR, a clinical decision support alert was created to prompt medical assistants to offer HIV testing using a simple script that met New York State requirements.

Once the provider saw the HIV test being offered, and patients confirmed their desire to be tested, acceptance was documented in a structured data field. The Medical Information Systems data analyst extracted data on HIV test offer and testing from structured fields in the EMR using the Crystal Reports®15 system to create data-based reports stratified by site, department, and individual provider. The HIV testing coordinator routinely reviewed data graphs, which included test and offer rates, and then circulated this information via electronic messaging to health-care providers who viewed both their data and that of their colleagues. The HIV testing coordinator also reviewed the individual chart of any HIV-positive patient to ensure the patient was scheduled for an appointment with an HIV specialist.

Up to 2010, UHP conducted point-of-care, rapid, and/or laboratory-based HIV tests. From January 2011 onward, UHP used an onsite commercial laboratory, BioReference Laboratories, for HIV blood testing, which relied on an HIV antibody assay using a chemiluminescent technique and subsequent Western blot for HIV infection confirmation.

This study examined the number of individuals eligible for HIV testing, the number of HIV tests offered, the number of tests performed, the number of detected HIV seropositives, and the number of observed cases linked to HIV specialist care. In alignment with the 2010 New York State HIV testing law,16 the data reported were inclusive for individuals aged 13–64 years who had no documented HIV test during the previous 12 months.

For the 2010 base year, eligible individuals included those patients at UHP clinics who requested HIV testing and/or those known to be at high risk for HIV infection (i.e., injection drug users, individuals having multiple sex partners, bisexual and gay men, individuals not using condoms, and those with an existing sexually transmitted infection). For the 2011–2013 implementation study period, eligible individuals included all patients offered an HIV test at UHP clinics. Offered HIV test numbers were determined only for the 2011–2013 time period and not for the 2010 baseline year, as the post-2011 period involved the time frame when new HIV screening implementation occurred.

HIV test numbers were defined as the number of HIV tests performed among eligible individuals at UHP clinics during the 2010–2013 period. We did not report the number of patients who declined HIV testing or the reasons for refusal. Seropositive numbers were defined as the number of individuals who tested positive for HIV during the 2010–2013 period. Linkage-to-care numbers were defined as the number of HIV-positive patients who had a scheduled appointment with a local HIV care specialist following a positive HIV test at any of the UHP clinics.

RESULTS

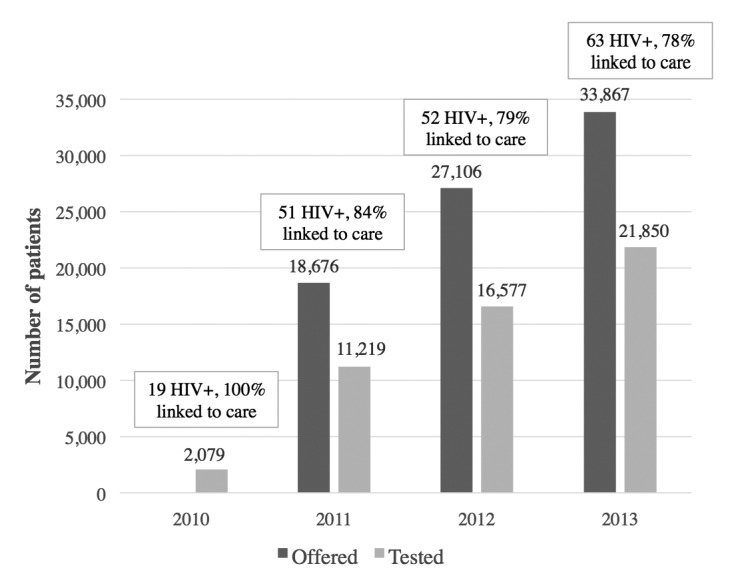

A total of 26,853 patients were eligible for HIV screening at UHP in 2010. During the three-year project implementation period, from January 1, 2011, through December 31, 2013, 100,369 patients were eligible for HIV testing at UHP. Among the eligible patients during 2011–2013, 63,873 (64%) were female, 83,998 (84%) were Hispanic, and 57,423 (57%) used Medicaid as their primary health insurance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of patients eligible for HIV testing at Urban Health Plan, Inc., clinics in the Bronx and Queens, New York, 2010–2013

aNA indicates that the site did not participate in the implementation process until 2013.

bNot all percentages total to 100 due to rounding.

cEl Nuevo San Juan Health Center, Plaza Del Sol Health Center, Plaza Del Castillo Health Center, and Bella Vista Health Center participated in both the baseline and implementation process and were eligible to offer HIV testing. The other sites were established during the implementation phase and began offering HIV testing in 2013.

dUnknown includes missing or “don't know” responses.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

NA = not applicable

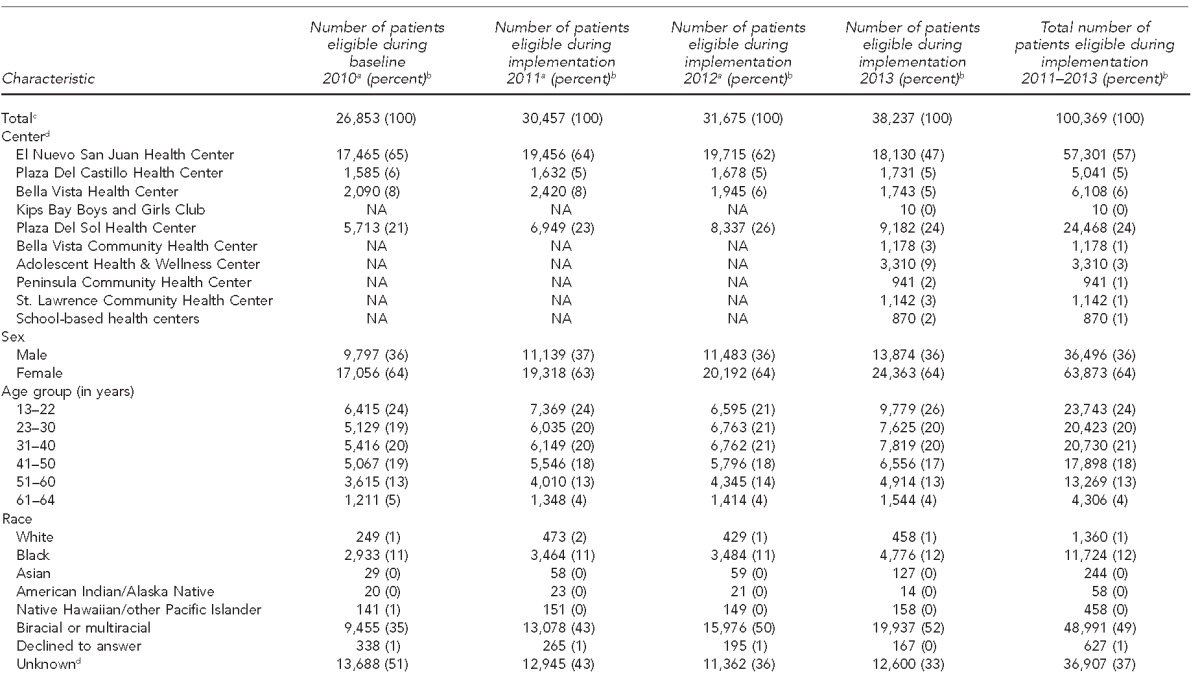

HIV testing was offered to 79,649 (79%) of 100,369 eligible patients during the implementation period (Table 2). The percentage of patients offered HIV testing increased during 2011–2013, from 18,676 (61%) of 30,457 eligible patients in 2011 to 33,867 (89%) of 38,237 eligible patients in 2013 (Figure 2). El Nuevo San Juan Health Center and Plaza Del Sol Health Center, representing UHP's main and largest sites, offered HIV testing to 11,974 (62%) of 19,456 eligible individuals and 3,819 (55%) of 6,949 eligible individuals, respectively, in 2011; those numbers increased to 15,261 (84%) of 18,130 eligible individuals and 8,669 (94%) of 9,182 eligible individuals, respectively, in 2013 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patients who were offered an HIV test, tested, diagnosed HIV-positive, and linked to care at Urban Health Plan, Inc., clinics in the Bronx and Queens, New York, 2010–2013a

At baseline (2010), the health center used a counselor-based HIV screening model. During the implementation phase (2011–2013), the health center changed to one in which health-care providers and medical assistants offered HIV testing.

bNo patients were offered an HIV test.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

NA = not applicable

Figure 2.

Number of HIV-seropositive patients detected and percentage of HIV-seropositive patients linked to HIV specialist care in Urban Health Plan, Inc., clinics in the Bronx and Queens, New York, 2010–2013a

aAt baseline, the health center used a counselor-based HIV screening model. During the implementation phase, the health center changed to one in which health-care providers and medical assistants offered HIV testing.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

Compared with the 2,079 (8%) of 26,853 eligible patients tested in 2010 at UHP clinics, the number and percentage of patients tested increased substantially each year during the implementation period: 11,219 (37%) of 18,676 eligible patients in 2011, 16,577 (52%) of 27,106 eligible patients in 2012, and 21,850 (57%) of 33,867 eligible patients in 2013. Specifically, the El Nuevo San Juan Health Center and Plaza Del Sol Health Center saw increases from 1,138 (7%) and 95 (2%) of 26,853 eligible individuals tested in 2010 to 10,323 (57%) and 5,648 (62%) of 38,237 eligible individuals tested in 2013, respectively. The number of HIV tests conducted at El Nuevo San Juan Health Center and Plaza Del Sol Health Center increased about eightfold and 58-fold, respectively, from 2010 to 2013 (Table 2).

The number of HIV-positive tests increased from 19 (0.9%) of 2,079 eligible individuals in 2010 to 166 (0.3%) of 49,646 eligible individuals during the 2011–2013 implementation period among HIV-tested individuals. Of the 166 HIV-positive individuals, 51 were tested in 2011, 52 were tested in 2012, and 63 were tested in 2013. Three of the eligible 19 patients from 2010 and 55 (33%) of the eligible 166 patients from 2011–2013 were newly diagnosed HIV cases. Linkage to HIV specialty care among those testing HIV positive was observed in all 19 eligible patients in 2010 and 127 (77%) of the 166 eligible patients in 2011–2013 (Table 2). Each health-care provider was responsible for offering HIV testing to all patients aged 13–64 years at least once in their lifetime, as described in the New York State HIV testing law of 2010.16 The two providers, from El Nuevo San Juan (2010–2012) and Adolescent Health & Wellness Center (2013) and Plaza Del Sol Health Center (2010–2013), were champions in their respective sites for the incremental number of observed HIV tests performed over time. Provider 1 offered testing to 15 (2%) of 900 eligible patients in 2010 compared with 1,294 (98%) of 1,321 eligible patients in 2013, and the HIV testing of that provider rose from seven (1%) of 900 eligible patients in 2010 to 1,039 (79%) of 1,321 eligible patients in 2013. Similarly, Provider 2 offered HIV testing to 85 (23%) of 370 eligible patients in 2010 compared with 787 (93%) of 844 eligible patients in 2013, and the HIV testing for this provider rose from 30 (8%) of 370 eligible patients in 2010 to 614 (73%) of 844 eligible patients in 2013 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

HIV offer and testing data for two Urban Health Plan, Inc., health-care providers in the Bronx and Queens, New York, during baseline (2010) and implementation periods (2011–2013)a

aEach health-care provider was responsible for offering HIV testing to all patients aged 13–64 years at least once in their lifetime. These graphs show HIV offer and testing data for two health-care providers during baseline and implementation periods. At baseline, the health center used a counselor-based HIV screening model. During the implementation phase, the health center changed to one in which health-care providers and medical assistants offered HIV testing.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

LESSONS LEARNED

UHP's collaborative learning HIV testing project was successful in increasing routine HIV screening across all practice sites when a counselor-based HIV screening model was changed to one in which health-care providers and medical assistants offered HIV testing. The new screening model was also able to sustain an increase in those screened for HIV during the first three years after implementation.

The reasons for the program's success are numerous: supportive institutional changes in policy; systematic training of health-care providers and medical assistants; EMR modifications for documenting HIV test offers and testing; sharing and tracking data performance; and, especially, providers' willingness to conduct routine HIV screening. Integrating screening into the regular clinical workflow made the program scalable, and the active HIV linkage to specialty care was an essential element of its success.10,17

The UHP collaborative benefited from the New York State HIV testing law, which requires that an HIV test be offered to all patients aged 13–64 years. This law positively affected our health-care providers' acceptability of the project. As a result, this type of project is more applicable to health centers in states with similar mandates than in those that do not have such statutes in place. As a result, health community organizations that lack funding support for EMR modifications, data management, care coordination activities, personnel for linkage to specialty care, and upgrades to laboratory testing may likely face difficulty implementing a similar HIV screening program.

Limitations

Our data were subject to several limitations. HIV testing outcomes were for individuals already enrolled in a health-care system and not for the entire Bronx and Queens populations, as the goal of UHP's HIV screening project was to increase HIV testing among individuals who visited one of the UHP clinics. As such, UHP's observed HIV testing data cannot be generalized for the Bronx and Queens populations. It also explains why UHP's observed HIV seropositivity level of <0.1% is lower than the 1.7% seropositivity level reported for the South Bronx.18

Additionally, although data were collected and analyzed for individual health-care provider's HIV tests offered and ultimately performed, we did not specifically study health-care providers with consistently high acceptance numbers to determine what they did differently. Thus, our study did not specify the exact provider attitudes that affected test numbers.

CONCLUSION

Our work suggests that system-wide implementation of an HIV screening collaborative learning approach at a network of community health centers can provide a backbone for increased routine HIV testing, which can result in increased HIV detection and enhanced linkage to HIV specialty care.

Footnotes

The authors thank the patients and medical staff of the Urban Health Plan clinics. This project was funded by Gilead Sciences, Inc., as part of its HIV on the Frontlines of Communities in the United States program. The authors also acknowledge the support of Maja Zecevic, PhD, MPH, a Gilead Sciences, Inc. paid consultant, for providing editorial guidance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) HIV Surveillance Report. No. 3. Vol. 19. Atlanta: CDC; 2014. Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 dependent areas—2012. Also available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/surveillance_report_vol_19_no_3.pdf [cited 2014 Sep 23] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) HIV Surveillance Report. No. 4. Vol. 17. Atlanta: CDC; 2012. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2007–2010. Also available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_hssr_vol_17_no_4.pdf [cited 2014 Sep 23] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall HI, Holtgrave DR, Maulsby C. HIV transmission rates from persons living with HIV who are aware and unaware of their infection. AIDS. 2012;26:893–6. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328351f73f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacKellar DA, Hou SI, Whalen CC, Samuelsen K, Sanchez T, Smith A, et al. Reasons for not HIV testing, testing intentions, and potential use of an over-the-counter rapid HIV test in an Internet sample of men who have sex with men who have never tested for HIV. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38:419–28. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31820369dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joseph HA, Fasula AM, Morgan RL, Stuckey A, Alvarez ME, Margolis A, et al. “The anticipation alone could kill you”: past and potential clients' perspectives on HIV testing in non-health care settings. AIDS Educ Prev. 2011;23:577–94. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.6.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwarcz S, Richards TA, Frank H, Wenzel C, Hsu LC, Chin CS, et al. Identifying barriers to HIV testing: personal and contextual factors associated with late HIV testing. AIDS Care. 2011;23:892–900. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.534436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith A, Miles I, Le B, Finlayson T, Oster A, DiNenno E, et al. Prevalence and awareness of HIV infection among men who have sex with men—21 cities, United States, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(37):1201–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Broz D, Wejnert C, Pham HT, DiNenno E, Heffelfinger JD, Cribbin M, et al. HIV infection and risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among injecting drug users—National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System, 20 U.S. cities, 2009. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2014;63(6):1–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. HIV surveillance annual report, 2013. 2014 [cited 2015 Jul 14] Available from: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/dires/2013-hiv-surveillance-annual-report.pdf.

- 10.Lin X, Dietz PM, Rodriguez V, Lester D, Hernandez P, Moreno-Walton L, et al. Routine HIV screening in two healthcare settings—New York City and New Orleans, 2011–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(25):537–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Community health profiles. 2006 [cited 2015 Jul 14] Available from: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/data/2006chp-107.pdf.

- 12.Newbhard IM. Learning and improving in quality improvement collaborative: which collaborative features do participants value most? Health Serv Res. 2009;44:359–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002;288:1775–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langley GJ, Moen R, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CL, Provost LP. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2009. The improvement guide: a practical approach to enhancing organizational performance. [Google Scholar]

- 15.SAP SE. SAP® Crystal Reports®: Version 11. Walldorf (Germany): SAP SE; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16. NYS Public Health Law. Laws of 2010, Ch. 308 (2012)

- 17.Sanchez TH, Sullivan PS, Rothman RE, Brown EH, Fitzpatrick LK, Wood AF, et al. A novel approach to realizing routine HIV screening and enhancing linkage to care in the United States: protocol of the FOCUS program and early results. JMIR Res Protoc. 2014;3:e39. doi: 10.2196/resprot.3378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. The Bronx knows: HIV testing initiative final report. 2011 [cited 2014 Sep 23] Available from: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/ah/bronx-knows-summary-report.pdf.