Abstract

Objective

The HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) 065 trial sought to expand HIV screening of emergency department (ED) patients in Bronx, New York, and Washington, D.C. This study assessed the testing costs associated with different expansion processes and compared them with costs of a hypothetical optimized process.

Methods

Micro-costing studies were conducted in two participating EDs in each city that switched from point-of-care (POC) to rapid-result laboratory testing. In three EDs, laboratory HIV testing was only conducted for patients having blood drawn for clinical reasons; in the other ED, all HIV testing was conducted with laboratory testing. Costs were estimated through direct observation and interviews to document process flows, time estimates, and labor and materials costs. A hypothetical optimized process flow used minimum time estimates for each process step. National wage and fringe rates and local reagent costs were used to determine the average cost (excluding overhead) per completed nonreactive and reactive test in 2013 U.S. dollars.

Results

Laboratory HIV testing costs in the EDs ranged from $17.00 to $23.83 per completed nonreactive test, and POC testing costs ranged from $17.64 to $37.60; cost per completed reactive test ranged from $89.29 to $123.17. Costs of hypothetical optimized HIV testing with automated process steps were approximately 45% lower for nonreactive tests and 20% lower for reactive tests. The cost per ED visit to conduct expanded HIV testing in each hospital ranged from $1.21 to $3.96.

Conclusion

An optimized process could achieve additional cost savings but would require an investment in electronic system interfaces to further automate testing processes.

Of the 1.1 million people in the United States living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), approximately 14% are unaware of their HIV infection.1 These individuals are not receiving appropriate medical care and are at a disproportionately high risk of transmitting HIV to their partners, contributing to the approximately 47,500 people who become infected with HIV in the United States each year.2 The “test and treat” prevention model, which includes routine testing of individuals to detect HIV infection early and links HIV-infected people to antiretroviral therapy immediately upon diagnosis, could play a central role in curbing the HIV epidemic.

In support of this model, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends opt-out HIV screening as part of routine clinical care for adults and adolescents in all health-care settings.3 Currently, all states except Nebraska have laws that are consistent with CDC's recommendations.4,5 Single-center studies have shown that routine HIV testing is feasible in a variety of health-care settings, including emergency departments (EDs).6–10 Nevertheless, uptake of these recommendations by health-care providers has been slowed by a lack of perceived HIV risk among ED patients11 and lack of reimbursement by public and private insurers.12,13 In 2013, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended routine HIV screening for adults with a Grade A recommendation (i.e., there was high certainty that the net benefit was substantial), and, under the Affordable Care Act, private insurers are required to cover tests with this recommendation without copayments from patients.14 However, the reimbursement amount to providers is not specified, and hospitals may still have difficulty obtaining reimbursement that is separate from negotiated fixed payments for ED visits.

The HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) 065 trial evaluated the feasibility of an enhanced test, linkage to care, plus treat approach for HIV prevention in the United States.15 One component of this 36-month, community-level trial was for 17 sites located in Bronx, New York, and Washington, D.C.(DC), to attempt universal offers of HIV testing to ED patients and hospital inpatients. This component was conducted in the context of ongoing social mobilization and HIV testing expansion efforts in both communities. Hospital leadership and medical staff members were encouraged to add HIV testing to established laboratory testing order procedures for ED patients (standing orders), to use novel mechanisms to deliver information about HIV testing to patients, and to perform testing with rapid-result laboratory HIV testing platforms that could expand testing volumes when compared with point-of-care (POC) testing and allow detection of acute HIV infections.16 On average, fewer than 20% of patients in both cities were tested during ED visits, and the percentage of HIV-positive tests exceeded the 0.1% threshold for routine screening, as recommended by CDC.17

Given the need to address potential reimbursement barriers and minimize the cost of screening, we collected data from four hospitals participating in this component of the trial to determine the cost of expanded POC and laboratory HIV testing in their EDs. We also calculated the hypothetical cost of an optimized ED laboratory HIV testing process.

METHODS

Overview

We conducted interviews and collected cost data from July 2013 through September 2014 from four HPTN 065 participant hospitals in the Bronx and DC that had switched from POC to rapid-result laboratory testing for some or all ED patients. Adults seeking medical services in the ED were offered an HIV test if they met hospital-specific eligibility criteria that included no recent documented HIV test (three or six months, depending on the hospital) and no self-report of HIV infection. Costs are reported in 2013 U.S. dollars and do not include overhead costs (e.g., costs of supervision, administration, space, and utilities). We performed analyses in Microsoft® Excel® 2013.

Process flow and time estimates

To document ED HIV testing practices, we conducted in-person interviews at each hospital with laboratory personnel and counselors involved in HIV testing and linkage-to-care processes. Interviews lasted approximately one hour. We also conducted observations to better understand overall ED process flows. To determine times for each step of the process, we asked laboratory personnel and counselors to describe how much time was typically required for each step. We used data on the average number of HIV tests conducted to assign a portion of the time required to run HIV controls for each test. The time estimates excluded downtime (i.e., when testing was not being performed) because we assumed personnel performed other unrelated activities. As a result, estimates might represent a lower bound of actual labor time associated with POC or laboratory testing.

We then synthesized data collected during interviews and observations to map HIV testing process flows and time durations for lower acuity urgent care (fast-track) ED patients, who generally do not have blood drawn unless they are offered and accept laboratory HIV testing, and for other ED patients who generally require a blood draw for clinical purposes. Three of the hospitals chose to conduct POC HIV testing for fast-track ED patients. We summarized the process steps for each track as follows: provide information about HIV testing, confirm HIV screening eligibility, order HIV test, collect specimen, process HIV test, deliver and document results (nonreactive), deliver and document results (reactive), perform HIV confirmatory testing on-site or off-site, and link to care.

Cost analysis

We used micro-costing methods18 similar to those in our previous economic analyses of HIV testing in substance abuse treatment programs19 and in sexually transmitted disease clinics20 to determine the cost of conducting HIV testing in the four EDs. Where possible, we used national labor costs to compare our findings across institutions.21 We applied national wage and fringe rates22 to time estimates for each process step. To calculate the cost of laboratory HIV testing, we obtained the cost of reagents and controls from each hospital and the cost of laboratory equipment from one hospital that used a third-generation HIV assay and one that used a fourth-generation HIV assay. Both assays detect HIV infection earlier than POC tests by using equipment that can produce HIV test results in less than one hour and can perform tests other than HIV.16

Laboratory equipment costs included service contracts and annualized costs for equipment purchase, assuming straight-line depreciation during a four-year contract term, or annual leasing costs. To assign a portion of the equipment costs to each HIV test, we used data on the number of HIV tests performed and the percentage of HIV tests conducted with the equipment. For confirmatory HIV testing, we used the national rate23 if the confirmatory test was performed by an outside laboratory, or the hospital's cost if its laboratory conducted the confirmatory test. We used national costs from a survey of health departments for the cost of POC HIV tests.24 Further details on labor and materials costs are available on request.

Costs are reported as cost per nonreactive HIV test result, cost per reactive HIV test result, and cost per ED visit to conduct HIV testing. We calculated cost per test result by summing the labor and materials costs for each relevant process step. To address potential budget impact, we calculated costs to conduct expanded HIV testing for each hospital and reported them as cost per ED visit. To calculate the cost per ED visit, we summed the labor and materials costs for each relevant process step, weighted by the percentage of ED patients who experienced that process step, and divided by the total number of ED visits. Each hospital provided data on ED admissions and the number of patients testing nonreactive and reactive for the relevant period ending January 2014 (ranging from three to 13 months) when the process flow was in place. In sensitivity analyses, we varied the percentage of ED patients receiving an HIV test and the percentage of tests with a reactive result.

Hypothetical optimized process

To construct a hypothetical optimized ED process flow for laboratory HIV testing, we compared time estimates for each process step across all EDs and selected the minimum time estimate required for each step. We calculated hypothetical optimized process costs per HIV test result using the fourth-generation HIV assay and equipment. We assumed that (1) personnel assigned to conduct each step and the materials used in the step were the same as those used by the hospital with the most efficient process for that step or (2) personnel assigned to conduct each step were the lowest-cost personnel involved in that step at any hospital, and materials used were the lowest-cost materials reported by any hospital.

RESULTS

Process flows and time estimates

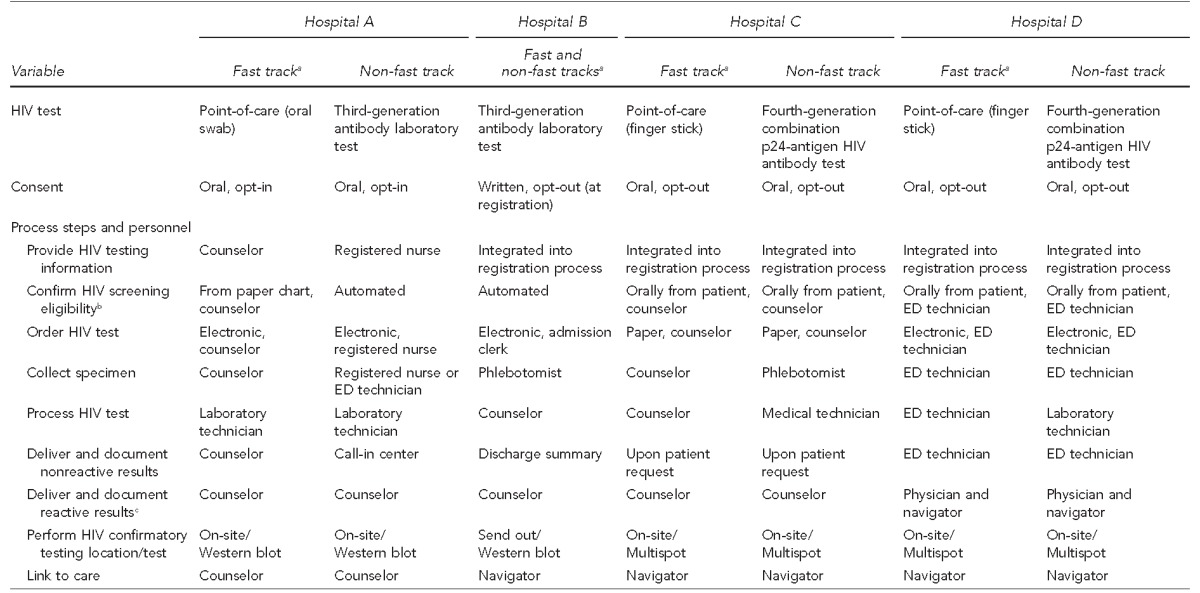

We examined the type of HIV test, type of consent, and process flow for each hospital (Table 1). Hospitals A, C, and D conducted POC HIV testing for fast-track ED patients and laboratory HIV testing for other ED patients; Hospital B conducted laboratory HIV testing for both fast-track and other ED patients. Hospitals A and B were using third-generation laboratory assays, and Hospitals C and D were using fourth-generation laboratory assays.

Table 1.

Description of type of HIV test, type of consent, process steps, and personnel performing HIV screening at four emergency departments in the Bronx, New York, and Washington, D.C., observed during the period July 2013–September 2014

aFast track refers to lower acuity urgent care.

bEligibility criteria for offering a patient an HIV test included: not known to be HIV infected and ≤65 years of age at Hospital A; not known to be HIV infected, not tested for HIV within the previous six months, and aged 18–65 years at Hospital B; not known to be HIV infected and not tested in the last six months at Hospital C; and not known to be HIV infected and not tested in the last three months at Hospital D.

cProvider delivering reactive results in ED is usually a physician, but may be a physician assistant.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

ED = emergency department

All hospitals obtained oral consent prior to collecting a specimen except Hospital B, which obtained written opt-out consent at registration. The process of providing information about HIV testing varied among hospitals. A separate information and consent step occurred at Hospital A, whereas Hospitals B, C, and D integrated information about HIV testing into the registration process. Confirmation of eligibility for HIV testing was automated using data from the electronic medical record (EMR) for all patients at Hospital B and for non-fast-track ED patients at Hospital A. At the remaining hospitals, obtaining eligibility information required manual review of paper records or requesting it orally from the patient. Similarly, hospitals differed based on whether the HIV test was ordered electronically or using a paper-based system, and in the types of personnel who ordered the test, collected the specimen, and processed the test (Table 1).

Processes for delivery of nonreactive results to patients also varied across hospitals. At Hospital A, counselors delivered nonreactive results to fast-track patients; other patients could obtain their nonreactive results from a call-in center. Hospital B provided nonreactive results as part of the ED discharge summary. In Hospital D, ED technicians delivered nonreactive results, and Hospital C did not actively deliver nonreactive results to ED patients on a routine basis. In contrast, all hospitals followed similar processes to deliver reactive results, conduct confirmatory HIV testing, and link patients to care, although the personnel who conducted these tasks and the confirmatory tests differed (Table 1).

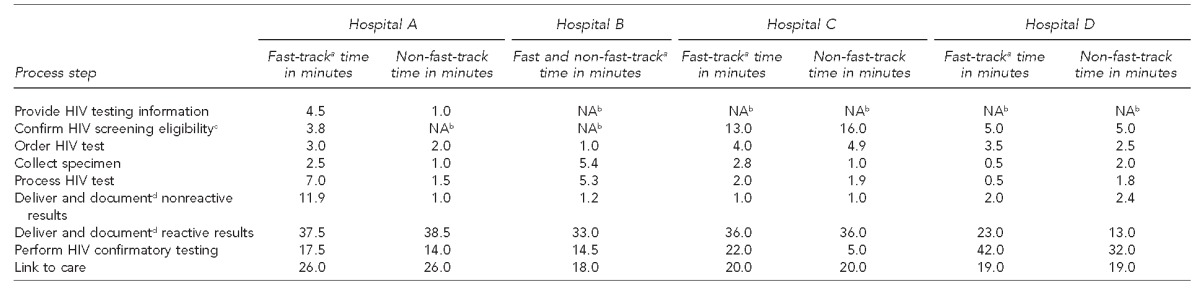

We also estimated times to complete each process step. The process step was incorporated into the standard registration process or was automated with no additional labor time required, when no time estimate was indicated. The process of confirming screening eligibility at Hospital C, which the counselor conducted and which included an additional verification step to safeguard against unauthorized HIV screening, took substantially longer (13.0–16.0 minutes) than at the other hospitals (0.0–5.0 minutes). The time required to order tests and collect samples also varied by hospital, depending on the type and complexity of the ordering and documentation systems (e.g., manual vs. electronic) and whether samples were collected separately or during an existing blood draw. Documentation and delivery of nonreactive results by counselors at Hospital A in the fast track took 11.9 minutes, substantially longer than delivery of results by ED technicians at Hospital D (2.0 minutes), because counselors at Hospital A also required time to find and enter documentation in the paper chart, whereas results at Hospital D were automatically entered into the EMR (Table 2).

Table 2.

Estimated times for HIV testing process steps, by ED track, at four hospitals in the Bronx, New York, and Washington, D.C., observed during the period July 2013–September 2014

aFast track refers to lower acuity urgent care.

bThe process step was incorporated into the standard registration process or was automated, and no additional labor time was required.

cThe process of confirming screening eligibility at Hospital C included an additional verification step to safeguard against unauthorized HIV screening.

dThe process of documenting HIV test results in the electronic medical record is automated at Hospital D.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

ED = emergency department

NA = not applicable

All hospitals required substantial time for documentation and delivery of reactive test results (13.0–38.5 minutes) and linkage to care (18.0–26.0 minutes). Times for confirmatory testing varied widely depending on whether the confirmatory test was processed immediately in the laboratory on the initial specimen or on an additional blood sample obtained separately, and on whether the confirmatory test was conducted on-site or sent to an outside laboratory for processing (Table 2).

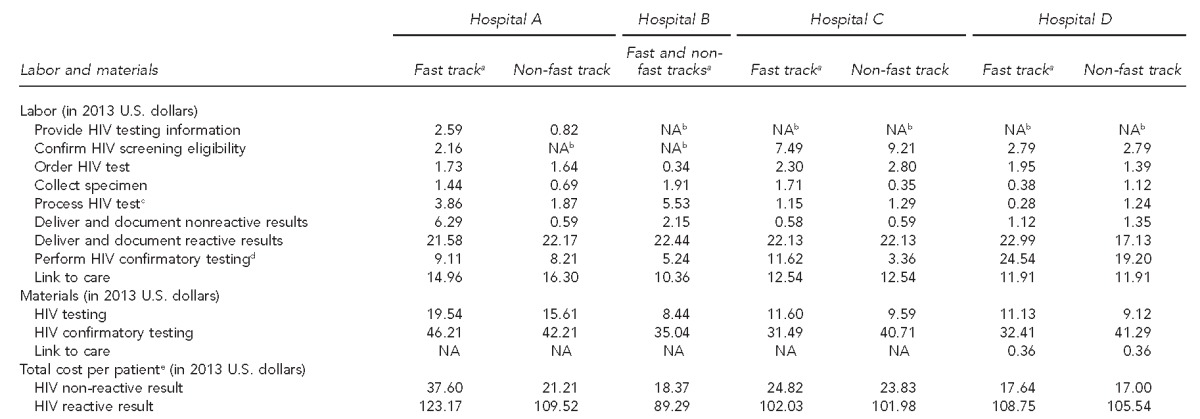

Costs for patients completing all testing steps

We calculated the labor and materials costs for each testing step in each ED and the estimated total cost per patient who completed the HIV testing process with either a nonreactive or reactive result (Table 3). The cost of laboratory HIV testing materials ranged from $8.44 at Hospital B to $15.61 at Hospital A (Table 3); the cost components (reagents, controls, and equipment and service contract costs) varied widely by hospital and equipment type (supplemental table available upon request). The cost of POC HIV testing materials ranged from $11.13 at Hospital D to $19.54 at Hospital A depending on test brand. For a patient with a nonreactive result, the cost of completing a laboratory HIV test ranged from approximately $17.00 at Hospital D to $23.83 at Hospital C, and the cost of completing a POC test ranged from $17.64 at Hospital D to $37.60 at Hospital A. For a patient with a reactive result, the cost of completing a laboratory HIV test ranged from $89.29 at Hospital B to $109.52 at Hospital A, and the cost of a POC test ranged from $102.03 at Hospital C to $123.17 at Hospital A (Table 3).

Table 3.

Estimated labor and materials costs for HIV testing, by process step and ED track, at four hospitals in the Bronx, New York, and Washington, D.C., observed during the period July 2013–September 2014

aFast track refers to lower acuity urgent care.

bThe process step was incorporated into the standard registration process or was automated, and no additional labor cost was incurred.

cIncludes labor cost of running controls for point-of-care, third-generation, or fourth-generation HIV tests

dIncludes labor cost of running controls for Multispot confirmatory HIV tests, in-house only

eFor patients completing the testing process

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

ED = emergency department

NA = not applicable

Hypothetical optimized process cost

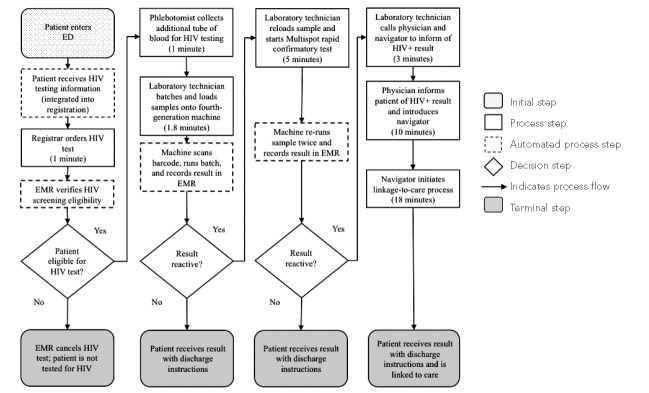

We created a hypothetical optimized process flow for non-fast-track patients using the minimum estimate required at each step across all EDs. Briefly, the optimized process flow for patients receiving nonreactive results was assumed to be: provision of information about HIV testing integrated into the registration process, HIV test ordered by registrar at registration (1 minute), automated verification of HIV screening eligibility by an EMR interface, blood collection by a phlebotomist at triage (1 minute), batching and loading blood samples by laboratory technician with automated barcode scanning (2 minutes), automated documentation, and delivery of nonreactive results as part of discharge instructions (Figure).

Figure.

Hypothetical optimized process flow of expanded rapid-result laboratory HIV testing in emergency departments based on four hospitals in the Bronx, New York, and Washington, D.C., observed during the period July 2013–September 2014

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

ED = emergency department

EMR = electronic medical record

We compared the labor and materials costs for each step and total costs per patient who completed the HIV laboratory testing process for the hypothetical optimized process flow with the labor and materials costs for each testing step in each ED and the estimated total cost per patient who completed the HIV testing process with either a nonreactive or reactive result. The cost of completing an HIV test with a nonreactive result using this hypothetical optimized process was $11.05 based on personnel and materials costs from the hospitals with the minimum process time for each step, which was approximately 45% lower than the median observed laboratory HIV testing cost. Substituting lowest-cost personnel and materials for the actual costs incurred in hospitals with the minimum process time did not substantially lower the cost (Table 4).

Table 4.

Estimated ED HIV testing costs with and without hypothetical optimized process flow at four hospitals in the Bronx, New York, and Washington, D.C., observed during the period July 2013–September 2014

aIf cost equals zero, step was automated with no incremental cost.

bOnly one hospital had a cost for completing this step; this step was integrated into the registration process with no additional labor time required at all other hospitals.

cFourth-generation laboratory cost only

dMultispot confirmatory test cost only

ED = emergency department

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

For patients with reactive results, the hypothetical optimized process flow assumed that confirmatory testing was performed on-site and the experience at Hospital D, where medical providers reported spending 10 minutes delivering the results before introducing the patients to navigators for linkage to care. The hypothetical optimized process cost for patients receiving a reactive result was $82.61; the cost would be lowered to $72.19 if counselors, instead of medical providers, could deliver these results in 10 minutes. Because of the small number of reactive results reported by each hospital, however, the total cost savings from changes in the process for delivering reactive results would be small (Table 4).

Cost to conduct expanded HIV testing

The average number of ED admissions per month at the four hospitals ranged from approximately 3,500 to 6,000. The percentage of all ED admissions tested for HIV ranged from 5% to 16%, and the percentage of those with a reactive result ranged from 0.3% to 2.3%. The cost per ED visit to conduct POC and laboratory HIV testing was $1.21 at Hospital B, $3.36 at Hospital A, $3.83 at Hospital C, and $3.96 at Hospital D. Results were sensitive to assumptions about the number of ED patients tested. For example, if 50% of all patients at all hospitals were tested, the cost per ED visit to conduct testing would range from $9.29 at Hospital B to $29.96 at Hospital A (supplemental table available upon request). Results were not sensitive to possible variation in the percentage of patients with reactive test results because the additional costs for reactive results were incurred for only a small number of patients.

DISCUSSION

We conducted a micro-costing study in four hospitals participating in HPTN 065 that had switched from POC to rapid-result laboratory testing for some or all of their patients who received HIV screening in the ED. We found that after this switch, laboratory HIV testing in the EDs cost approximately $17.00–$23.83 per completed nonreactive test. In three hospitals, POC testing was retained for fast-track patients who generally did not have blood drawn for clinical reasons; the cost per completed nonreactive test using POC testing was $17.64–$37.60. These costs were similar to those reported in our previous economic analyses of POC HIV testing in sexually transmitted disease clinics20 and substance abuse treatment programs19 ($18–$26, excluding overhead) and in other studies of ED HIV screening programs using POC tests ($16–$19, excluding program management costs.25,26 Laboratory testing has the potential for lower costs vs. POC testing due to batch processing; some laboratory tests have the potential for cost savings due to consumption of fewer controls. In this study, however, we did not observe consistent cost patterns across these testing modalities. This finding is likely due to substantial variation among the hospitals in testing volumes and HIV testing process flows. For example, we found in a sensitivity analysis that if hospitals increased their current testing volumes to 50% of all ED admissions, the cost to conduct HIV testing per ED visit would increase by $8.08 at a hospital using rapid-result laboratory testing or by $26.61 at a hospital where fast-track patients received POC testing using a relatively expensive process flow.

We also found that an optimized process could achieve additional cost savings, but achieving these savings would require investments in electronic system interfaces to further automate testing processes. These investments require both time and resources; for example, a bioinformatics specialist at one hospital reported that a project to automate confirmation of HIV test eligibility was conducted in three phases during 10 months and required an estimated 316 hours of consultant programmer time and 64 hours of in-house project management time.

Limitations

Our analysis was subject to several limitations. We deliberately selected four hospitals that had successfully switched from POC to rapid-result laboratory testing for some or all of their ED patients. However, these hospitals are not representative of all 17 sites participating in the expanded HIV testing component of HPTN 065. Also, because the labor time estimates excluded downtime, and we were unable to include overhead costs, our estimates were lower than the total costs to the hospitals for conducting HIV testing and should not be extrapolated (e.g., to consider the adequacy of insurance reimbursement levels for these services). Downtime costs and some overhead costs were principally associated with labor costs, however, and in the hypothetical optimized process, flow automated processes replaced many labor costs. The estimated cost of the hypothetical optimized process, therefore, may more accurately reflect ultimate total hospital costs. Additionally, our cost estimates were based on current testing volumes at each hospital. At higher testing volumes, materials costs for laboratory testing would be lower because costs of controls, equipment, and service contracts would be amortized over a larger number of tests.

CONCLUSION

We found that costs of HIV testing varied widely among four hospitals that had successfully switched from POC to rapid-result laboratory HIV testing for expanded screening of ED patients. We estimated that using a hypothetical optimized process flow with automated steps could reduce costs by approximately 45% for patients with nonreactive results. These observations provide a basis for targeting efforts to optimize process flows and methods for estimating costs that, in EDs that screen patients for HIV, might be incorporated into negotiated agreements for fixed payments for ED services. In addition to ensuring appropriate reimbursement for HIV screening tests in the ED setting, policy makers and hospital leaders should seek financing for electronic system interfaces to further automate HIV testing processes.

Footnotes

The authors thank the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) 065 study staff members and hospital staff members and administrators at the four hospitals in Bronx, New York, and Washington, D.C., for their assistance with data collection; and Kate Buchacz, PhD, for her review and comments on a previous version of this article.

HPTN 065 is sponsored by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (cooperative agreements #UM1 AI068619 and #UM1 AI068617); the National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIAID, NIMH, the National Institutes of Health, or CDC.

The Copernicus Group Institutional Review Board approved all HPTN 065 study procedures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. No. 3. Vol. 19. Atlanta: CDC; 2014. Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 dependent areas—2012. Also available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/surveillance_report_vol_19_no_3.pdf [cited 2015 Apr 24] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. No. 4. Vol. 17. Atlanta: CDC; 2012. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2007–2010. Also available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_hssr_vol_17_no_4.pdf [cited 2015 Apr 24] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, Janssen RS, Taylor AW, Lyss SB, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) State HIV testing laws: consent and counseling requirements [cited 2015 Apr 24] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/policies/law/states/testing.html.

- 5.New York State Department of Health. HIV testing public health law 2014 amendments [cited 2015 Apr 24] Available from: http://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/aids/providers/testing.

- 6.Brooks L, Rietmeijer CA, McEwen D, Subiadur JA, Mettenbrink CJ. Normalizing HIV testing in a busy urban sexually transmitted infections clinic. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:127–8. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318191701c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hack CM, Scarfi CA, Sivitz AB, Rosen MD. Implementing routine HIV screening in an urban pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29:319–23. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3182850910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoxhaj S, Davila JA, Modi P, Kachalia N, Malone K, Ruggerio MC, et al. Using nonrapid HIV technology for routine, opt-out HIV screening in a high-volume urban emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(Suppl 1):79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin X, Dietz PM, Rodriguez V, Lester D, Hernandez P, Moreno-Walton L, et al. Routine HIV screening in two health-care settings—New York City and New Orleans, 2011–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(25):537–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maxwell CJ, Sitapati AM, Abdus-Salaam SS, Scott V, Martin M, Holt-Brockenbrough ME, et al. A model for routine hospital-wide HIV screening: lessons learned and public health implications. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102:1165–72. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30771-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shirreffs A, Lee DP, Henry J, Golden MR, Stekler JD. Understanding barriers to routine HIV screening: knowledge, attitudes, and practices of healthcare providers in King County, Washington. PloS One. 2012;7:44417. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rizza SA, MacGowan RJ, Purcell DW, Branson BM, Temesgen Z. HIV screening in the health care setting: status, barriers, and potential solutions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:915–24. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White BL, Walsh J, Rayasam S, Pathman DE, Adimora AA, Golin CE. What makes me screen for HIV? Perceived barriers and facilitators to conducting recommended routine HIV testing among primary care physicians in the southeastern United States. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2015;14:127–35. doi: 10.1177/2325957414524025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin EG, Schackman BR. What does U.S. health reform mean for HIV clinical care? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60:72–6. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824c0dd4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institutes of Health (US) TLC-Plus: a study to evaluate the feasibility of an enhanced test, link to care, plus treat approach for HIV prevention in the United States [database on the Internet]. 2010 [cited 2015 Apr 24] Available from: URL: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01152918.

- 16.Branson BM. The future of HIV testing. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(Suppl 2):102–5. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fbca44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chavez PR, Greene E, Buchacz K, Gamble T, Ethridge SF, McKinstry L, et al. Expanding HIV testing in hospital emergency departments and inpatient admissions: findings from the HPTN 065 (TLC-Plus) study. Presentation at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2015 Feb 23–26; Seattle, Washington. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Polsky D, Glick H. Costing and cost analysis in randomized controlled trials: caveat emptor. Pharmacoeconomics. 2009;27:179–88. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200927030-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schackman BR, Metsch LR, Colfax GN, Leff JA, Wong A, Scott CA, et al. The cost-effectiveness of rapid HIV testing in substance abuse treatment: results of a randomized trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;128:90–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eggman AA, Feaster DJ, Leff JA, Golden MR, Castellon PC, Gooden L, et al. The cost of implementing rapid HIV testing in sexually transmitted disease clinics in the United States. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41:545–50. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, Weinstein MC. Cost effectiveness in health and medicine. 1st ed. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Department of Labor (US) National compensation survey; 2013 [cited 2015 Apr 24] Available from: http://www.bls.gov/data.

- 23.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (US) Clinical laboratory fee schedule. 2013 [cited 2015 Apr 24] Available from: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ClinicalLabFeeSched/index.html?redirect=/ClinicalLabFeesched/02_clinlab.asp.

- 24.National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors. Update on implementation of HIV rapid testing in health department supported HIV prevention programs; 2011 [cited 2015 Apr 24] Available from: http://www.nachc.com/client/documents/NASTAD%202011%20Rapid%20Testing%20Report_May%20 2011.pdf.

- 25.Dowdy DW, Rodriguez RM, Hare CB, Kaplan B. Cost-effectiveness of targeted human immunodeficiency virus screening in an urban emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18:745–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haukoos JS, Campbell JD, Conroy AA, Hopkins E, Bucossi MM, Sasson C, et al. Programmatic cost evaluation of nontargeted opt-out rapid HIV screening in the emergency department. PloS One. 2013;8:81565. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]