Abstract

Objective

This study compared two approaches for implementation of non-targeted HIV screening in the emergency department (ED): (1) designated HIV counselors screening in parallel with ED care and (2) nurse-based screening integrated into patient triage.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was performed to compare parallel and integrated screening models using data from the first 12 months of each program. Data for the parallel screening model were extracted from information collected by HIV test counselors and the electronic medical record (EMR). Integrated screening model data were extracted from the EMR and supplemented by data collected by HIV social workers during patient interaction. For both programs, data included demographics, HIV test offer, test acceptance or declination, and test result. A Z-test between two proportions was performed to compare screening frequencies and results.

Results

During the first 12 months of parallel screening, approximately 120,000 visits were made to the ED, with 3,816 (3%) HIV tests administered and 65 (2%) new diagnoses of HIV infection. During the first 12 months of integrated screening, 111,738 patients were triaged in the ED, with 16,329 (15%) patients tested and 190 (1%) new diagnoses. Integrated screening resulted in an increased frequency of HIV screening compared with parallel screening (0.15 tests per ED patient visit vs. 0.03 tests per ED patient visit, p<0.001) and an increase in the absolute number of new diagnoses (190 vs. 65), representing a slight decrease in the proportion of new diagnoses (1% vs. 2%, p=0.007).

Conclusion

Non-targeted, integrated HIV screening, with test offer and order by ED nurses during patient triage, is feasible and resulted in an increased frequency of HIV screening and a threefold increase in the absolute number of newly identified HIV-positive patients.

An estimated 1.1 million individuals in the United States are currently living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. An additional 50,000 individuals are infected with HIV each year—a rate that has remained stable since the late 1990s.1 Given the demonstrated efficacy of current antiretroviral regimens and the reduced side effects and decreased risk of HIV transmission among patients in treatment,2 a universal test-and-treat strategy has been proposed as a promising approach to significantly reduce new HIV infections and even stop the HIV pandemic.3–6

Both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)6 and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force7 have issued recommendations for routine, non-risk-based HIV screening in all clinical settings. Despite these recommendations, significant barriers exist to widespread implementation of non-targeted HIV screening in emergency departments (EDs),8 and the majority of EDs in the United States still do not have protocols in place for non-targeted HIV screening.9 Even among EDs that use an opt-out screening approach, most fall far short of screening all eligible patients, and many leave more than 80% of eligible patients unscreened.10

We compared data from two different approaches to opt-out HIV screening in the ED of a large, urban safety-net hospital: (1) designated HIV counselors screening in parallel with the ED medical care processes, known as the parallel screening model (PSM), and (2) nurse-initiated screening integrated into the ED triage process, known as the integrated screening model (ISM).

METHODS

We compared findings from two non-targeted HIV screening programs implemented at different times in the same ED. From 2008 through 2011, a PSM was in place that used designated counselors to perform HIV screening via a point-of-care oral swab test. In July 2013, an ISM was initiated in which HIV test offer and order were integrated into nurse triage, and HIV screening was performed via a serum-based HIV test. We compared data from the first 12 months of screening after implementation of each program.

Both screening models were implemented in the same ED within an urban safety-net hospital and Level I trauma center in a large southeastern city with high HIV prevalence. This ED currently has 110,000 patient visits annually. Approximately 80% of the patients are African American, many live in low-income households, and about 65% are self-pay/uninsured.

Patient selection

In both screening models, patients were eligible for HIV test offer if they were not previously known to be HIV positive, were >18 years of age, were cognitively capable of consent (e.g., not critically ill, not acutely psychiatrically ill, and not cognitively impaired), and were not incarcerated. Additionally, patients screened via ISM were not eligible for test offer if they had an HIV test result documented in the hospital electronic medical record (EMR) in the previous six months.

In the PSM, HIV screening was offered to ED patients from 10 a.m. to 10 p.m., Monday through Friday. Trained HIV counselors reviewed the triage list and approached eligible patients in consecutive order.

In the ISM, HIV test offer and order were integrated into routine ED triage processes using an HIV test offer eligibility assessment that was added to the nursing flow sheet in the EMR.

Consent process

In the PSM, a trained HIV counselor approached eligible patients and explained that HIV screening was part of routine medical care in the ED. Through the counselor's use of opt-out language, patients were given the opportunity to decline testing and, per hospital policy at that time, were asked to sign a form indicating their decision to accept or decline testing. Patients received oral pretest counseling. Hospital regulations required both written consent and oral pretest counseling during the time the PSM process was in place.11

In the ISM, after determining eligibility, triage nurses offered patients an HIV test using opt-out language and ordered the test for patients who did not decline. Per an amended hospital policy consistent with CDC recommendations, oral consent was sufficient for HIV testing in this health system. Written consent was no longer required, and pretest counseling was provided in reading level-appropriate written form.

Laboratory procedures and result disclosure/linkage to care

For patients tested via the PSM, the trained HIV counselor administered the OraQuick ADVANCE® Rapid HIV-1/2 Antibody Test (OraSure Technologies, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania) in the ED, and most patients were informed of their preliminary results during their ED visit. The hospital laboratory performed confirmatory Western blot (HIV-1, BioRad”, Foster City, California) analysis and CD4+ counts for all patients with reactive rapid tests. Due to laboratory procedures, Western blot and CD4+test results were not available on the same day as the preliminary result; therefore, these results were disclosed to patients at a follow-up visit scheduled within one week of the positive preliminary test. Patients with positive Western blots had an appointment scheduled at either the local health department or hospital-affiliated infectious disease program.11

Prior to initiation of the ISM, the ED transitioned from an oral swab-based HIV test to a serum-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test. Reasons for this change included improved integration into ED phlebotomy and laboratory processes, reduced cost for the serum tests, and a lower rate of false-positive results with serum testing vs. oral-swab testing.12

In the ISM, all patients who did not decline the opt-out test offer had blood drawn for a serum-based HIV enzyme immunoassay (EIA) test (Anti-HIV 1&2 EIA, Ortho Diagnostics, Rochester, New York), followed by a reflex Western blot (HIV-1, BioRad) if the ELISA was reactive. The hospital laboratory used a platform for ELISA testing that was capable of giving results to providers within three hours; thus, most preliminary results were available while patients were still present in the ED. When an ELISA test was reactive, laboratory personnel contacted the treating physician and the HIV social worker, from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m., Monday through Friday. When the HIV social worker was not available, the attending physician disclosed the ELISA test reactive result, and the social worker received a list of all positive results at 8 a.m. on the following business day.

The aforementioned Western blot results were typically available within three days of initial positive ELISA, and patients returned to meet with the social worker after this result was available. During this visit, the social worker initiated the process of linking each patient to HIV care. The HIV social worker maintained contact with each diagnosed patient until the patient completed two appointments with an HIV care provider.

In both models, if patients were lost to follow-up (i.e., initial contact was made, but later the patient became unreachable) or provided incorrect or incomplete contact information, the patient's information was provided to the county health department, which used its outreach team to attempt to locate the patient and continue the linkage-to-care process.

Case definition

In both models, a patient was designated as newly diagnosed if, during posttest counseling, (1) the patient confirmed no prior HIV-positive test result, (2) review of hospital laboratory data did not reveal a prior positive test result in the health system, and (3) the county health department did not report a previous diagnosis (this information was shared routinely, though not systematically).

Data collection

PSM data were extracted from demographic information collected by HIV test counselors during test offer and pretest counseling. Additional laboratory data, including Western blot and CD4+ count, were obtained via the EMR. Data reported here are from the first 12 months of screening (May 1, 2008, through April 30, 2009).

ISM data were extracted from program quality-improvement reports available in the EMR for all ED patients, including demographics and HIV test offer, response, and result. These reports were supplemented by data collected by HIV social workers during patient interaction; these data included verification of demographic information, prior HIV status, and prior HIV test history. Data reported here are from the first 12 months of screening (from July 9, 2013, through June 30, 2014).

Statistical analysis

We stored and managed all data in secure, password-protected databases (Microsoft® Excel® 2010 and REDCap13) and we analyzed data using SAS® version 9.3.14 We performed a Z-test between two proportions to compare screening frequencies and results.

RESULTS

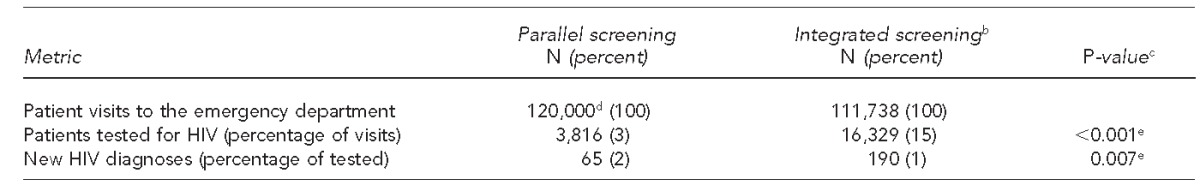

During the first 12 months of the PSM, approximately 120,000 visits were made to the ED; 3,816 (3%) individuals were tested for HIV (Table 1), 65 of whom (2%) had a new positive HIV diagnosis. During the first 12 months of the ISM, 111,738 patients were triaged in the ED, representing 67,098 unique patients. A total of 16,329 (15%) patients were tested for HIV, resulting in 190 (1%) new HIV diagnoses (Table 1). Unique patient data or precise visit counts were not available for the PSM, as the hospital did not use a widespread EMR system during that time.

Table 1.

HIV tests performed, patients tested, and new HIV diagnoses identified using parallel vs. integrated screening modelsa in a large, urban southeastern U.S. hospital emergency department, 2008–2013

In the parallel screening model, designated HIV counselors screened for HIV in parallel with emergency department care. In the integrated screening model, nurse-based screening was integrated into patient triage.

bNumber of patient visits based on count of actual patients triaged

cZ-test between two proportions comparing parallel and integrated screening

dEstimated number of patient visits

eDifference is significant at α=0.05.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

Implementation of the ISM resulted in a fivefold increase in HIV test frequency (0.15 tests per ED patient visit via the ISM vs. 0.03 tests per ED patient visit via the PSM, p<0.001) and a threefold increase in the absolute number of new HIV diagnoses (190 in the ISM vs. 65 in the PSM) (Table 2). However, the percentage of new HIV infections identified in the ISM was lower than in the PSM (1% vs. 2%, p=0.007).

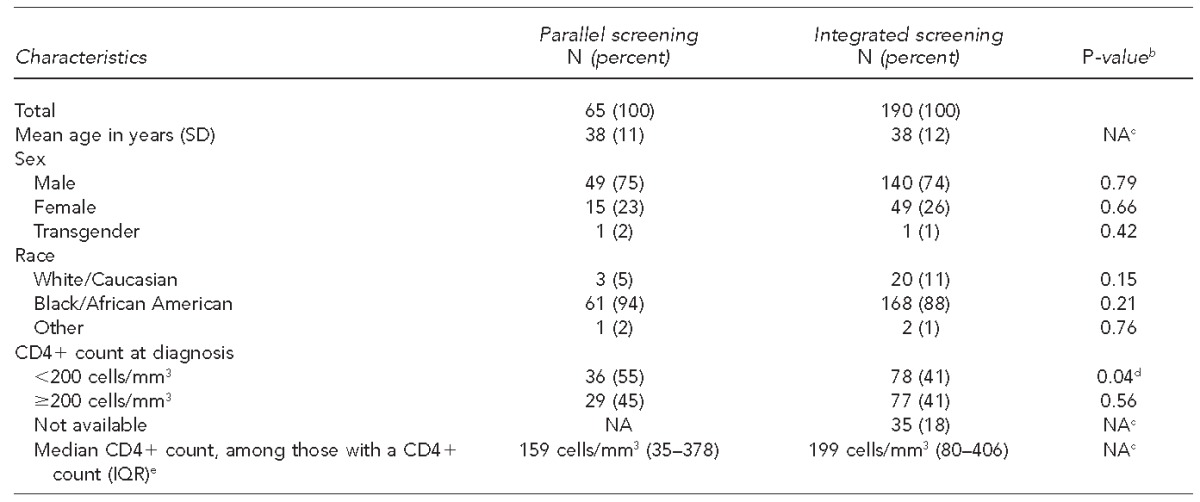

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients newly diagnosed with HIV using parallel vs. integrated screening modelsa at a large, urban southeastern U.S. hospital emergency department, 2008–2013

In the parallel screening model, designated HIV counselors screened for HIV in parallel with emergency department care. In the integrated screening model, nurse-based screening was integrated into patient triage.

bZ-test between two proportions comparing parallel and integrated screening

cRaw data were not available to make a direct statistical comparison.

dDifference significant at α=0.05

eBased on protocols for both models, patients had to return to the hospital to have blood drawn for the CD4+ count. CD4+ count was not available for patients who did not return to the hospital for this blood draw.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

SD = standard deviation

NA = not available

IQR = interquartile range

mm3 = cubic millimeter

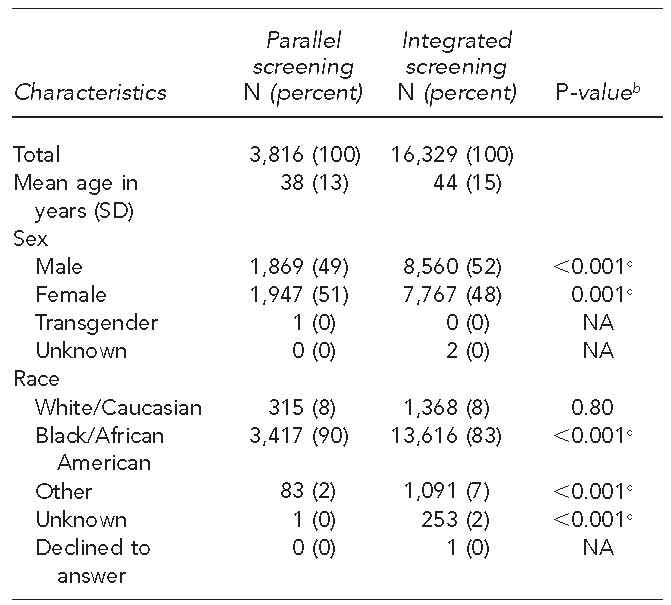

Both screening models served patients with similar demographic characteristics, although small, statistically significant differences between the populations of patients tested were noted. For example, a higher proportion of black/African American patients was screened in the PSM than in the ISM (90% vs. 83%), and a higher proportion of males was screened in the ISM than in the PSM (52% vs. 49%) (p<0.001). At testing time, the average patient age in the PSM was 38 years (standard deviation [SD] = 13 years) and in the ISM was 44 years (SD=15 years) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of patients tested for HIV in parallel vs. integrated screening modelsa at a large, urban southeastern U.S. hospital emergency department, 2008–2013

In the parallel screening model, designated HIV counselors screened for HIV in parallel with emergency department care. In the integrated screening model, nurse-based screening was integrated into patient triage.

bZ-test between two proportions comparing parallel and integrated screening

cDifference significant at α=0.05

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

SD = standard deviation

NA = not applicable

Comparing the PSM with the ISM, newly diagnosed patients were primarily black/African American (94% and 88%, respectively) and male (75% and 74%, respectively), with a mean age of 38 years at diagnosis in both models. Demographic characteristics of newly diagnosed patients did not vary substantially between the two models. Both screening programs identified a high proportion of patients with an initial CD4+ count of <200 cells per cubic millimeter at diagnosis, although the PSM led to identification of a higher proportion of patients with an initial low CD4+ count (55% in the PSM and 41% in the ISM) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

When comparing the frequency of HIV testing in the first 12 months of each program, the ISM approach resulted in a significantly higher proportion of ED patients tested compared with the PSM. In one year, implementation of the ISM resulted in nearly 13,000 more patients tested for HIV and 125 additional new HIV-positive patients diagnosed.

The decrease in the proportion of new HIV-positive patients identified when comparing the PSM with the ISM (2% vs. 1%, p=0.007) is worth exploring. Two possible factors may explain the decreased incidence of new HIV diagnoses among patients tested under the ISM. First, it is possible that the PSM, where designated HIV counselors approached each patient to offer and perform testing, allowed for a selection bias to emerge. Although unintended, patients of particular at-risk demographics or chief complaints may have been more likely to be approached and/or more likely to consent. Second, the prevalence of undiagnosed HIV infection among the patients served by the hospital may have declined during the interval between the two screening models, potentially as a result of increased screening efforts at other clinical settings and by the county health department during this interval.

We also found that neither model achieved the goal of screening a large proportion of ED patients. The ISM, which achieved higher screening implementation than the PSM, still resulted in 85% of ED patients who were not tested for HIV. It is important to note that the total number of patients seen in the ED included a large number of repeat visits: There were only 67,098 unique visits among more than 111,000 total visits during the ISM period (i.e., 60% of total visits were unique). Given the nature of emergency medicine, some patients will appropriately not be screened for reasons such as declining testing when offered, a prior HIV diagnosis, a recent HIV test, or an acute clinical or psychiatric illness impeding capacity for opt-out consent.

From an operational standpoint, our team found that the ISM had several logistical benefits compared with the PSM. First, an ISM is scalable and provides screening coverage 24 hours a day, seven days a week. At a PSM, the number of HIV tests conducted is ultimately limited by the number of designated HIV counselors and their scheduled availability. Second, although the ISM approach required additional effort to initially engage all clinical staff members to change the triage process, it led to changes in clinical practice and culture that facilitated ongoing screening process sustainability. Finally, integrating the HIV test offer into the medical care a patient receives upon arrival in the ED had benefits with respect to patients' experience of the screening offer; it laid the foundation for patients to view HIV screening as yet another routine blood test to expect when visiting a health professional.

Limitations

This study was subject to several limitations, many of which stem from the design—a historical comparison between two testing processes instead of a randomized, side-by-side comparison of two models. First, patient inclusion, exclusion, and selection processes differed between the two models; in the PSM, testing personnel approached waiting and roomed patients to offer and then perform the oral swab test. This limitation may partially explain the difference in demographic characteristics among patients tested by the two models (i.e., a higher percentage of black/African American patients tested by the PSM and a higher percentage of men tested in the ISM). Also, other unmeasured differences may have led to selection bias, such as a propensity to test patients with lower clinical acuity in the PSM, because sicker patients would have been brought back to the treatment area more quickly and may not have been available for the tester to approach due to their clinical condition. Additionally, because of a change in hospital policy, written consent for HIV screening was no longer required during the ISM, a change that may have led to a larger segment of the population participating in screening.

Another limitation to our analysis was the time lapse between the time intervals selected for comparing the two models. Given the operational challenges involved in implementing a new, department-wide protocol change, we felt it most appropriate to compare the first 12 months of each program rather than the final year of the PSM and the first year of the ISM. However, comparing the final year of the PSM would still have demonstrated a large gap in the number of tests performed in the PSM as compared with the ISM, because the budget constrained the number of HIV counselors and the hours of testing. The only mechanism to increase testing within the PSM would have been to add counselors/testing hours, which was not feasible given the program's fixed budget.

CONCLUSIONS

Non-targeted, integrated HIV screening by ED nurses during patient triage resulted in an increased frequency of HIV screening compared with parallel screening at the same institution. Integrated HIV screening led to an increase in screening from 0.03 tests per ED visit to 0.15 tests per ED visit, and resulted in more than 12,500 additional patients tested and 125 additional new HIV diagnoses during the course of 12 months. This research adds to the body of literature about HIV screening in a high-volume ED setting, a site that is very important from a public health perspective. ED screening provides the opportunity to test patients who may not be tested elsewhere, despite the challenge of achieving high rates of HIV screening implementation, even within the context of an integrated, serum-based, non-targeted HIV screening program. Future research is needed to identify approaches that lead to increased implementation of HIV screening in the ED, while minimizing additional costs and personnel time.

Footnotes

The funding for the parallel screening model was obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC's) Expanded and Integrated HIV Testing Initiative and was administered through the Georgia Department of Health & Wellness. Funding for the integrated screening model was obtained from Gilead Sciences, Inc.'s Frontlines of Communities in the United States (FOCUS) program.

The Emory University Institutional Review Board and the hospital's Research Oversight Committee approved these programs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moore RD. Epidemiology of HIV infection in the United States: implications for linkage to care. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(Suppl 2):208–13. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dieffenbach CW, Fauci AS. Universal voluntary testing and treatment for prevention of HIV transmission. JAMA. 2009;301:2380–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wood E, Kerr T, Marshall BD, Li K, Zhang R, Hogg RS, et al. Longitudinal community plasma HIV-1 RNA concentrations and incidence of HIV-1 among injecting drug users: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2009;338:1649. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marks G, Crepaz N, Janssen RS. Estimating sexual transmission of HIV from persons aware and unaware that they are infected with the virus in the USA. AIDS. 2006;20:1447–50. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000233579.79714.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, Janssen RS, Taylor AW, Lyss SB, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moyer VA U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for HIV: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:51–60. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-1-201307020-00645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mumma BE, Suffoletto BP. Less encouraging lessons from the front lines: barriers to implementation of an emergency department-based HIV screening program. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(Suppl 1):44–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haukoos JS, Hopkins E, Hull A, Dean C, Donahoe K, Ruzas CM, et al. HIV testing in emergency departments in the United States: a national survey. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(Suppl 1):10–6. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haukoos JS, Hopkins E, Bucossi MM. Routine opt-out HIV screening: more evidence in support of alternative approaches? Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41:403–6. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wheatley MA, Copeland B, Shah B, Heilpern K, Del Rio C, Houry D. Efficacy of an emergency department-based HIV screening program in the Deep South. J Urban Health. 2011;88:1015–9. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9588-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delaney KP, Branson BM, Uniyal A, Kerndt PR, Keenan PA, Jafa K, et al. Performance of an oral fluid rapid HIV-1/2 test: experience from four CDC studies. AIDS. 2006;20:1655–60. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000238412.75324.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.SAS Institute, Inc. SAS®: Version 9.3 for Windows. Cary (NC): SAS Institute, Inc.; 2012. [Google Scholar]