SUMMARY

Numerous studies of the anti-HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein 41 (gp41) broadly neutralizing antibody 4E10 suggest that 4E10 also interacts with membrane lipids, but the antibody regions contacting lipids and its orientation with respect to the viral membrane are unknown. Vaccine immunogens capable of re-eliciting these membrane proximal external region (MPER)-like antibodies may require a lipid component to be successful. We performed a systematic crystallographic study of lipid binding to 4E10 to identify lipids bound by the antibody and the lipid-interacting regions. We identified phosphatidic acid, phosphatidylglycerol, and glycerol phosphate as specific ligands for 4E10 in the crystal structures. 4E10 used its CDRH1 loop to bind the lipid head groups, while its CDRH3 interacted with the hydrophobic lipid tails. Identification of the lipid binding sites on 4E10 may aid design of immunogens for vaccines that include a lipid component in addition to the MPER on gp41 for generation of broadly neutralizing antibodies.

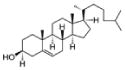

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Development of an anti-HIV vaccine is the most compelling approach to limiting the spread of HIV-1, as combination drug therapies (Chun and Fauci, 2012), although highly effective in reducing viral load and ensuing disease, are not yet able to effect a cure. However, vaccine design efforts are challenged by the high genetic variability of HIV-1. Neutralizing antibodies to HIV-1 target epitopes on the viral envelope glycoprotein (Env) (Walker et al., 2011), which assembles as a trimer of two non-covalently linked subunits, glycoprotein 120 (gp120) and gp41. The gp41 contains a C-terminal transmembrane region that anchors Env in the viral membrane (Tran et al., 2012).

HIV-1 enters the host by fusion of its membrane to the host cell membrane in a process initiated by binding of gp120 to CD4 and then to co-receptors CCR5 or CXCR4 (Chien et al., 2008). Receptor binding promotes Env conformational rearrangements leading to exposure of the gp41 hydrophobic N-terminal fusion peptide (Chien et al., 2008), which then inserts into the host cell membrane (Harrison, 2008). Gp41 is thought to initially adopt a metastable conformation that eventually collapses into the six-helix bundle post-fusion conformation after receptor and co-receptor engagement (Buzon et al., 2010), thereby bringing the viral and host membranes together to form the hemifusion stalk and fusion pore (Harrison, 2008).

The highly conserved membrane proximal external region (MPER) is proximal to the viral membrane in the gp41 ectodomain stem (Zwick, 2005) and critical for fusion, as its deletion abolishes cell fusion and infectivity (Salzwedel et al., 1999). Four neutralizing antibodies, 2F5, Z13e1, 4E10, and 10E8 (Cardoso et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2012; Julien et al., 2008; Ofek et al., 2004; Zwick et al., 2001), target the MPER. 4E10 and 10E8 (the most potent) recognize the same epitope (gp41 residues 671–683), but with different binding signatures (Huang et al., 2012). Although their potencies are lower than some other HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies (Walker et al., 2011), 4E10 and 10E8 exhibit the broadest neutralization capability (~98% of circulating HIV subtypes tested) of all known HIV antibodies (Huang et al., 2012). Due to its extraordinarily broad neutralization, 4E10 has been extensively studied (Brunel et al., 2006; Cardoso et al., 2007; Zwick et al., 2001), but how exactly 4E10 and 10E8 access their antigen in vivo in such close proximity to the viral membrane is still unknown. The MPER epitope recognized by 4E10 and 10E8 adopts an α-helical conformation when bound to each antibody (Cardoso et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2012) and is either proximal to, or partially laterally inserted into, the viral membrane (Sun et al., 2008). Several studies suggest that the MPER is occluded in the Env spike prior to CD4 binding and becomes briefly exposed during the fusion intermediate state (Frey et al., 2008; Rathinakumar et al., 2012), when it can be accessed by 4E10 and other anti-MPER antibodies. 4E10 also binds various lipids (Matyas et al., 2009) and its broad neutralization is thought to arise from interaction with an extended epitope comprising the MPER and viral membrane lipids (Scherer et al., 2010). Other studies suggest an alternate view in which 4E10 interacts with the viral membrane and then extracts the MPER epitope (Alam et al., 2009; Sun et al., 2008). However, the 4E10 orientation with regard to the gp41-viral membrane interface is unknown because no 4E10-gp41 fusion intermediate structure is available and the structures of soluble, stabilized BG505 strain Env trimer, truncated at residue 664 (BG505 SOSIP.664 Env) (Julien et al., 2013; Lyumkis et al., 2013; Pancera et al., 2014) are lacking the MPER, as well as the transmembrane and the cytoplasmic domains.

In healthy cells, the distribution of lipids across the plasma membrane is asymmetric, with sphingolipids located mostly in the external leaflet and amine-containing glycero-phospholipids phosphatidylserine (PS) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) mainly in the inner leaflet (van Meer et al., 2008). Phosphatidylcholine (PC) and sphingomyelin (SM, a choline-containing sphingolipid) are the main components of the external leaflet, forming a choline-rich surface. HIV-1 acquires its lipid envelope from the host cell plasma membrane during the budding process (Sundquist and Kräusslich, 2012). However, HIV-1 membranes are enriched in sphingolipids and sterols compared with host cell plasma membranes (Lorizate et al., 2013) with the major lipids being SM, plasmogen phosphatidylethanolamine (pl-PE), PC, PS, and PE; less abundant species are phosphatidylglycerol (PG), phosphatidic acid (PA), ceramide (CER), hexosylceramide, glucosylceramide, phosphatidylinositol (PI), phosphatidylinositolphosphates (PIP, PIP2), monosialodihexosylganglioside and cholesterol (Aloia et al., 1993; Lorizate et al., 2013).

Thus, a successful MPER-targeted immunogen design most likely needs to include a lipid component. To determine the structural basis for lipid interaction, we performed a systematic study of 4E10 with its best known lipid binders (Matyas et al., 2009) using X-ray crystallography. We found that glycerol-1-PO4, glycerol-3-PO4, 06:0 PA, and 06:0 PG specifically bound to 4E10 in the vicinity of the MPER in the 4E10 combining site. 4E10’s CDRH1 interacted with the lipid head groups and its CDRH3 with the lipid tails. This mode of binding allowed us to infer the angle of approach of 4E10 with regard to its MPER-viral membrane composite epitope.

RESULTS

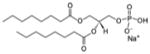

Lipid Selection for 4E10 Crystallographic Study

4E10 binds weakly to a large variety of lipids (Table S1), especially to glycero-phospholipids found in biological membranes (Figure S1) with the strongest binding to 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glyc-ero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol) (DMPG), PI, 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate (DMPA), cardiolipin (CL), and 1,2-dimyris-toyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DMPE) (Matyas et al., 2009). To avoid the use of organic solvents required to solubilize long lipids (acyl chains longer than 9 carbon atoms), we focused on crystallization experiments using water-soluble, short lipids (acyl chains shorter than 8 carbon atoms) or lipid head groups. Eighteen different soaking and co-crystallization regimens and compounds were tested (Table 1), and the best results were achieved by cryoprotecting crystals directly with lipid head groups dissolved in mother liquor (Table S2) or by co-crystallization of the Fab with short lipids (Table S3).

Table 1.

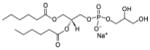

Lipids Used for 4E10 Co-crystallization and Crystal Soaking Experiments

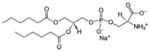

| Lipids type | Chemical name | Abbreviation | Chemical structure | Crystallization method | Lipid observed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short acyl chains glycero-phospholipids | 1,2-dihexanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate (sodium salt) | 06:0 PA |

|

Co-crystal 4E10 Fab-06:0 PA |

Yes |

| 1,2-dioctanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate (sodium salt) | 08:0 PA |

|

Lipid as cryoprotectant 4E10 Fab-MPER(671-683KKK)-08:0 PA |

No | |

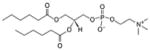

| 1,2-dihexanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol) (sodium salt) | 06:0 PG |

|

Co-crystal 4E10 Fab-06:0 PG |

Yes | |

| 1,2-dioctanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol) (sodium salt) | 08:0 PG |

|

Lipid as cryoprotectant 4E10 Fab-MPER(671-683KKK)*08062-08:0 PG* |

No | |

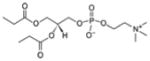

| 1,2-dihexanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine | 06:0 PC |

|

Co-crystal 4E10 Fab-06:0 PC |

No | |

| 1,2-dipropionyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine | 03:0 PC |

|

Lipid as cryoprotectant 4E10 Fab-MPER(671-683KKK)*0902-03:0 PC |

Yes | |

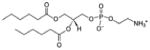

| 1,2-dihexanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine | 06:0 PE |

|

Co-crystal 4E10 Fab-06:0 PE Lipid as cryoprotectant 4E10 Fab-MPER(671-683KKK)-06:0 PE* |

No | |

| No | |||||

| 1,2-dihexanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine (sodium salt) | 06:0 PS |

|

Lipid cryoprotectant 4E10 Fab-MPER(671-683KKK)*0902-06:0 PS* |

No | |

| 1,2-dioctanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-myo-inositol-4′-phosphate) (ammonium salt) | 08:0 PI(4)P |

|

Lipid as cryoprotectant 4E10 Fab-MPER(671-683KKK)-08:0 PI(4)P* |

No | |

| Long acyl chains glycero-phospholipids | 1,1′,2,2′-tetra-(9Z-octadecenoyl) cardiolipin(sodium salt) | CL |

|

Co-crystal 4E10 Fab-MPER(671-683KKK)-CL* 4E10 Fab-CL* |

No |

| N/A | |||||

| Glycero-phospholipids head groups | rac-Glycerol-1-phosphate disodium salt hexahydrate | rac-glycerol-1-PO4 |

|

Lipid head as cryoprotectant 4E10 Fab-MPER(671-683KKK)*08062-glycerol-1-PO4 |

Yes |

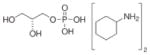

| sn-Glycerol-3-phosphate bis(cyclohexylammonium) salt | sn-glycerol-3-PO4 |

|

Lipid head as cryoprotectant 4E10 Fab-MPER(671-683KKK)*08062-glycerol-3-PO4 |

Yes | |

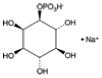

| D-myo-Inositol-1-phosphate (sodium salt) | 1-IP1 |

|

Lipid head as cryoprotectant 4E10 Fab-MPER(671-683KKK)-1-IP1* |

No | |

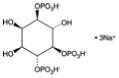

| D-myo-Inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate (sodium salt) | 1,4,5-IP3 |

|

Lipid head as cryoprotectant 4E10 Fab-MPER(671-683KKK)-1,4,5-IP3* |

No | |

| Sphingolipids | N-acetyl-D-erythro-sphingosylphosphorylcholine | 02:0 SM (d18:1/2:0) |

|

Lipid as cryoprotectant 4E10 Fab-MPER(671-683KKK)-02:0 SM (d18:1/2:0) |

No |

| Cholesterol | Cholesterol | Cholesterol |

|

Co-crystal 4E10 Fab-MPER(671-683KKK)-cholesterol* |

No |

Identification of 4E10 Region Interacting with Lipids in the Viral Membrane

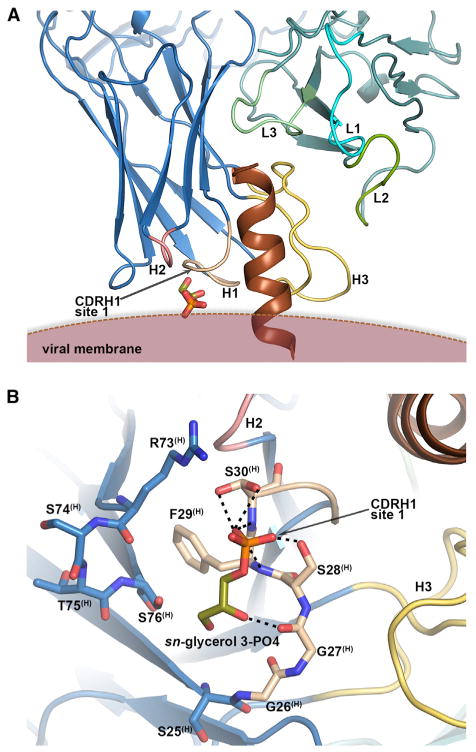

To identify the lipid binding sites on 4E10, we soaked the 4E10-peptide epitope crystals in short-chain lipid and lipid head group solutions. We found a putative lipid binding region in the immediate vicinity of the MPER binding site of 4E10 (Figure 1A). From the seven lipids and four lipid head groups tested (Table 1 and Table S2; 1.4–1.7 Å resolution), two lipidic compounds bound to this site: glycerol-1-PO4 and glycerol-3-PO4. Note that in glycero-phospholipids, glycerol-3-PO4 is linked to the fatty acid chains on carbons 1 and 2 via an ester bond (Figure S1) and glycerol-1-PO4 forms the head group in PG species. Electron density was observed for sn-glycerol-3-PO4 (Figures S2A and S2B), with its phosphate hydrogen bonding to Ser28(H), Phe29(H) and Ser30(H), and the glycerol moiety interacting with Gly27(H) of heavy-chain complementarity determining region (CDRH)1 (Figure 1B). This site will be referred to as the “CDRH1 site 1.” For rac-glycerol-1-PO4 (Table 1), density for C1-PO4 was observed at CDRH1 site 1 (Figures S2C and S2D). No such density was observed when crystals were cryoprotected with glycerol, other lipids, or different lipid head groups, suggesting that the electron density indeed corresponds to the glycerol-phosphates (Figure S2). CDRH1 site 1 was solvent exposed in the crystal and more than 10 Å from symmetry-related Fab molecules. These observations, together with the proximity of CDRH1 site 1 to the gp41 peptide C terminus (Figure 1A), suggest that CDRH1 site 1 is of biological relevance.

Figure 1. Lipid Binding Site in 4E10 CDRH1 Region as Revealed by Binding of sn-Glycerol-3-PO4 and rac-Glycerol-1-PO4.

(A) Crystal structure of 4E10 Fab (blue heavy chain and green light chain) bound to gp41 MPER peptide (brown) and sn-glycerol-3-PO4 (sticks). See also Figure S2. The CDRs (Chothia CDR boundaries) are labeled and colored as follows: H1 (wheat, residues 26–32), H2 (pink, residues 52–56), H3 (yellow, residues 95–102), L1 (cyan, residues 24–34), L2 (green, residues 50–56), and L3 (light green, residues 89–97). The same coloring and numbering scheme was used in all figures. The approximate position of the viral membrane was modeled based on the location of the peptide C-terminal residues 684–686 (replaced by lysines in the peptide used for crystallization), which would correspond to N-terminal residues of the gp41 transmembrane domain.

(B) Hydrogen bond interactions (dashed lines) of sn-glycerol-3-PO4 with CDRH1. See also Table S2.

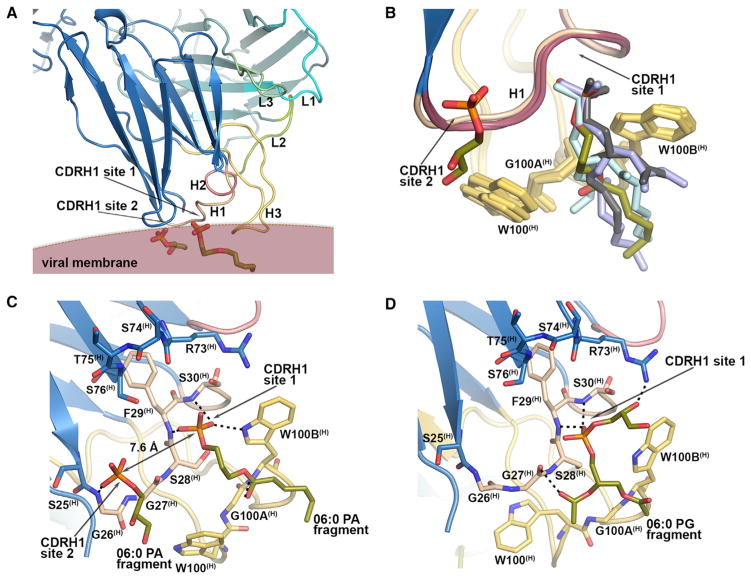

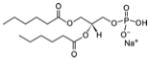

To further probe lipid binding, we performed co-crystallization experiments of 4E10 with five different, short acyl chain, glycero-phospholipids (Table 1) in the absence of peptide. From co-crystallization trials with 06:0 PA, 06:0 PG, 06:0 PC, 06:0 PE, and 06:0 PS lipids, all but 06:0 PS led to diffraction-quality crystals (2.73–2.93 Å resolution) with only 06:0 PG-4E10 complex diffracting to lower resolution (3.95 Å ; Table S3). The 4E10-06:0 PA and 4E10-06:0 PG structures confirmed that CDRH1 site 1 was indeed a lipid binding site (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Lipid Binding Site in 4E10 CDRH1 Region in Co-crystal Structures with 06:0 PA and 06:0 PG.

(A) Crystal structure (2.73 Å resolution) of 4E10 Fab with two fragments of 06:0 PA (one with only one ordered acyl tail and the other with only the head moiety) bound in the 4E10 CDRH1 region (see also Figure S4). The approximate position of the viral membrane is indicated considering the location of the 06:0 PA molecules.

(B) Superposition of all 4E10 Fabs in the 2.73 Å and 2.9 Å 4E10-06:0 PA asymmetric units containing the modeled fragments of 06:0 PA molecules in CDRH1. CDRH3 tryptophans are shown as yellow sticks. See also Figures S3 and S4.

(C) Hydrogen-bond interactions (dashed lines) of the polar heads of the bound 06:0 PA molecules with CDRH1.

(D) The 06:0 PG fragment bound in CDRH1 site 1. See also Figure S5 and Table S3.

The two 4E10-06:0 PA structures at 2.90 Å and 2.73 Å resulted from crystals obtained under similar conditions at different stages of seeding (see Experimental Procedures). Both datasets were indexed in spacegroup P6122 with similar cell parameters, but differed in the number of the 06:0 PA fragments that were observed in the six Fabs in the asymmetric unit. In the 2.90 Å structure, unequivocal electron density for an almost complete 06:0 PA was observed at CDRH1 site 1 in two Fabs (Figures S3A, S3B, S3D, and S3E), whereas three Fabs contained density for only a PO4 group (Figures S3G and S3H) and one Fab had no ligand bound. In the 2.73 Å structure, two 4E10 Fabs contained density for 06:0 PA fragments at CDRH1 site 1 (Figures S4A, S4B, S4D, and S4E), while the remaining four Fabs contained density only for the phosphate group that interacted with the main chain of Phe29(H) and Ser30(H) and with Trp100B(H) (Figure 2C, Figures S4G and S4H). Slight differences in the position and length of the acyl chain density in both structures suggested disorder of the flexible six-carbon hydrophobic tails (Figure 2B). Adjacent to CDRH1, additional electron density in the 2.73 Å structure in one of the six Fabs (Figures S4A, S4B, and S4C) was assigned to a sn-glycerol-3-PO4 that most likely arose from a second 06:0 PA with a disordered acyl tail (Figure 2B and Figure S4B). The phosphate in this site (“CDRH1 site 2”) was located 7.6 Å from the phosphate of the first 06:0 PA (Figure 2C) and hydrogen bonds to Gly 26(H) of CDRH1.

The 4E10-06:0 PG complex crystallized similarly to the 4E10-06:0 PA complex, but density for only the 06:0 PG headgroup (represented by sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol)) and the start of the acyl tails was observed in CDRH1 site 1 in two of the six 4E10 molecules in the asymmetric unit (Figure S5). The glycerol moiety of the PG head group was hydrogen bonded to Arg73(H) and its phosphate interacted with the main chain of Phe29(H) and Ser30(H) (Figure 2D). No electron density was found for 06:0 PC and 06:0 PE in their respective complexes. Thus, from our soaking and co-crystallization studies, we identified two lipid binding sites on 4E10 CDRH1 at the proximity of 4E10-MPER binding site where interaction with the viral membrane would be expected.

Binding of 06:0 PA and 06:0 PG to the CDRH1 Site Requires CDRH3 Involvement

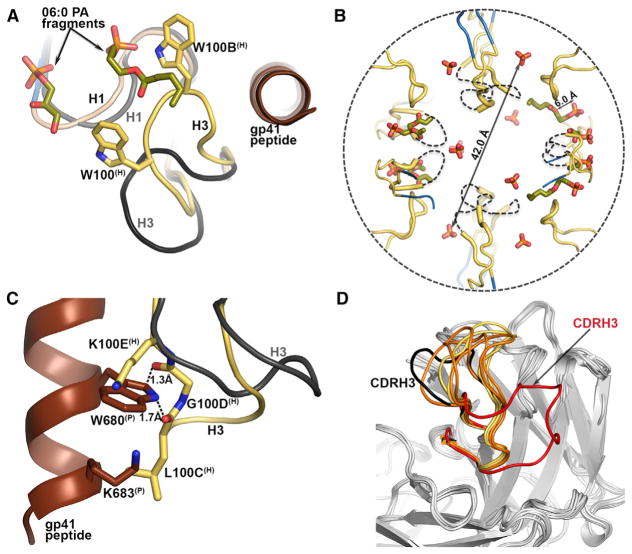

We further investigated the role of CDRH3 in the interaction. The 4E10-peptide complexes with glycerol-3-PO4 and glycerol-1-PO4, similar to 4E10-peptide (PDB 2FX7; Cardoso et al., 2007), showed weak density and high isotropic temperature factors (B-values) for Trp100(H), Gly100A(H), and Trp100B(H) at the CDRH3 tip. Only the main chain could be built in a conformation similar to that in the 2FX7 structure. Therefore, binding of glycerol-phosphates to CDRH1 site 1 did not induce conformational changes in CDRH3. Interestingly, 06:0 PA and 06:0 PG complexes had well-defined density for all CDRH3 residues in the Fab complexes that contained 06:0 PA or 06:0 PG (Figures S3C, S3F, S4C, S4F, S5C, and S5F). CDRH3 moved ~9.0 Å (as measured between Trp100B Cα in unbound and bound lipid structures) that was reflected by a 60° rotation toward the Fab-peptide combining site compared to the peptide-bound conformation (Figure 3A). However, in the remaining Fabs, for which only PO4 density or no ligand was observed, the CDRH3 tip was disordered (Figures S3I and S4I). The tails of the 06:0 PA fragments were sandwiched between CDRH3 Trp100(H) and Trp100B(H) (Figure 2B and 2C), consistent with models suggesting slight insertion of CDRH3 into the membrane (Alam et al., 2009).

Figure 3. CDRH3 Is Involved in Lipid Binding.

(A) The orientation of CDRH3 (yellow, with side chains of Trp100(H) and Trp100B(H) as sticks) in the lipid-bound complex compared to the peptide-glycerol-3-PO4 complex (black) as observed from superimposition of the 4E10 Fab-06:0 PA complex on the 4E10 Fab-peptide-glycerol-3-PO4 (gray Fab, brown peptide).

(B) Vesicular organization of the 06:0 PAs (green sticks) and PO4s (red-orange sticks) bound to the six 4E10 Fabs in the asymmetric unit and to their six crystallographic symmetry mates in the 4E10-06:0 PA complex. Only the CDRH3s and the bound PO4 and 06:0 PA fragments are shown here in a cross-section of the vesicle. Dashed lines approximate the positions of the missing regions of the CDRH3 loops.

(C) Superposition of 4E10 Fab-06:0 PA complex (yellow CDRH3) with 4E10 Fab-MPER(671-683KKK) (brown peptide, black CDRH3; PDB 2FX7; Cardoso et al., 2007). Side chains are shown for residues in close contact to peptide.

(D) Structures of the variable regions of 4E10 Fab obtained by co-crystallization with 06:0 PA, 06:0 PG, 06:0 PC, and 06:0 PE, and unliganded 4E10 scFv (PDB 4LLV; Finton et al., 2013) were superposed with the variable region of 4E10 in its peptide-liganded form (PDB 2FX7; Cardoso et al., 2007), with peptide omitted for clarity. CDRH3 (red) in unliganded 4E10 scFv occupies the peptide binding site. CDRH3 of the 4E10-peptide bound structure (PDB 2FX7) is highlighted in black and CDRH3s of 4E10-lipid co-crystal structures are in orange where the lipid was not observed (4E10-06:0 PE and 4E10-06:0 PC) and in yellow for structures where the respective lipid was bound (4E10-06:0 PA and 4E10-06:0 PG). See also Table S3.

Another striking feature of the 4E10-06:0 PA structure was its crystal packing. The 06:0 PA molecules from neighboring 4E10 Fabs were arranged in a spherical, micelle-like vesicle about 42 Å in diameter (Figure 3B). Twelve 4E10 Fabs were disposed on the surface of the “micelle” with their CDRH3 loops inserted inside the vesicle by ~6.0 Å as measured from the plane formed by the apical Trp100(H), Gly100A(H), and Trp100B(H) to the PO4 of the 06:0 PA fragment in corresponding site 1. Superposition of the 4E10 Fabs bound to 06:0 PA and to peptide epitope, respectively, revealed that CDRH3 in its lipid-bound conformation would form unfavorable steric clashes with the gp41 peptide in the combining site (Figure 3C). Although Lys100E(H) and Lys683(P) could easily adopt different conformations, Trp680(P) located in a restricted pocket, was within 1.3–1.7 Å of Leu100C(H) and Gly100D(H). To overcome this steric hindrance, Gly100D(H) and Leu100C(H) must reorient toward their positions in the Fab-MPER(671-683KKK) complex (PDB 2FX7). Recently, a structure of a single-chain 4E10 variable region (scFv) without peptide (PDB 4LLV) (Finton et al., 2013) showed a large reorganization of CDRH3, where Thr98(H)-Gly100H(H) are flipped into the peptide binding site (Figure 3D). We did not observe such an extensive CDRH3 reorganization in any of our five peptide-free 4E10-lipid co-crystal structures (Figure 3D). Our observations therefore suggested that, on the viral surface, either 4E10 interacts first with the membrane lipids and then accommodates its gp41 epitope as proposed by some studies (Alam et al., 2009; Sun et al., 2008) or a slight reorganization of the flexible CDRH3 occurs for concomitant binding of both lipid and peptide (Figure 4A).

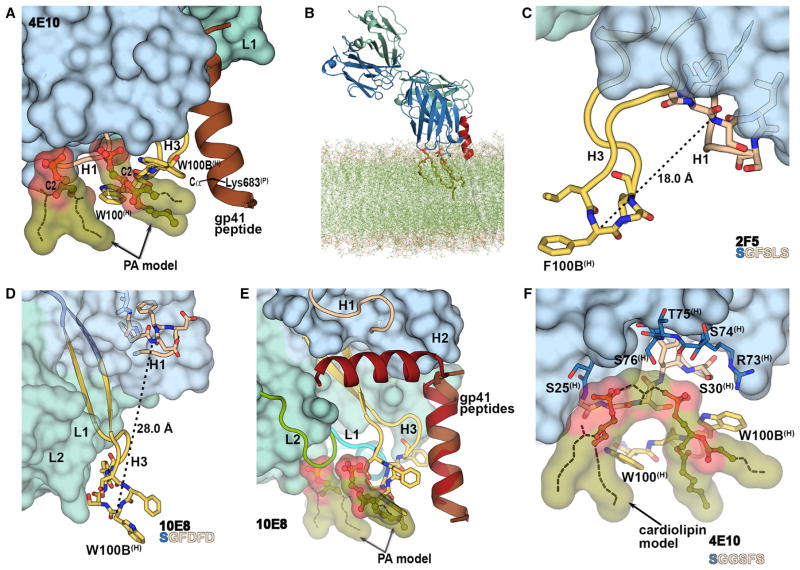

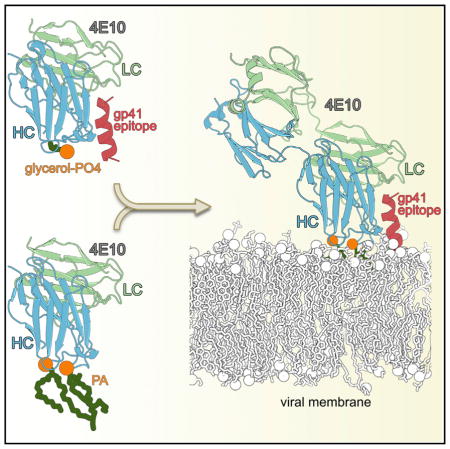

Figure 4. Structural Models for Concurrent Binding of 4E10 to gp41 and Lipid and Comparison with 2F5 and 10E8.

(A) Structural model for binding of 4E10 to gp41 and membrane lipids (PA modeled here). CDRH3 tryptophans and the gp41 peptide are shown as yellow sticks and brown helix, respectively. Dashed lines were added to complete the acyl chains of the observed 06:0 PA fragments (green ball-and-sticks).

(B) Angle of approach of 4E10 (blue and green) with respect to the model of gp41 epitope-viral membrane assembly. Only the MPER (red) for one of the protomers of the trimer model is shown for clarity. The lipids highlighted (stick representation) in the model were observed in our crystal structures.

(C) Position of CDRH3 (yellow) and CDRH1 (wheat) in 2F5 (PDB 2P8L) (Julien et al., 2008). The sequence of the displayed CDRH1 residues is shown at the bottom (as in E).

(D) Position of CDRH3 (yellow) and CDRH1 (wheat) in 10E8 (PDB 4G6F) (Huang et al., 2012).

(E) A model of lipid binding to 10E8, constructed by superposing residues 671-683 of the peptides in 4E10-MPER(671-673KKK) (PDB 2FX7; Cardoso et al., 2007) and 10E8-MPER(RRR656-683RRR) (Huang et al., 2012). The peptides bound to 4E10 and 10E8 are in brown and red, respectively. Only the 10E8 Fab and the position of the modeled PAs (green ball-and–stick) with regard to the MPER(671-683KKK) is shown for clarity.

(F) Model of cardiolipin binding to 4E10. A cardiolipin model (green ball-and-stick) was built after superposition of the 4E10-06:0PA and 4E10-glycerol-3-PO4 structures, by connecting the two phosphate moieties at CDRH1 site 1 and 2 by a glycerol bridge (dashes). The most complete fragment of 06:0 PA observed at the CDRH1 site 1 was used for construction of the model and dashed lines were used to complete the acyl chains. The sequence of the CDRH1 residues predicted to interact with the cardiolipin head is shown at the bottom, and color-coded to match the displayed residues. CDRH3 residues are represented as yellow sticks.

Structural Model for 4E10 Binding to gp41 Epitope-Viral Membrane and Comparison with Other MPER Neutralizing Antibodies

To gain some perspective on how 4E10 interacts with its extended epitope, we generated a model of the viral membrane (Figure 4B) using the CHARMM force field membrane builder (Brooks et al., 2009). The C2 atoms of the two experimentally identified lipids and the Cα atom of Lys683 (the last residue of the gp41 ectodomain) of the MPER epitope delineated a plane (C2PA-C2PA-CαLcs683) that would be coincident with the plane of the viral membrane (Figure 4A). The lipid bilayer was placed on a model that contained 4E10 bound to its gp41 epitope, a putative tri-helical gp41-transmembrane region, and the experimental lipids observed in our structures. As suggested from the orientation of the lipids in our crystal structures, the model was constructed with ~50° angle of approach of 4E10 to the gp41 epitope-membrane assembly and a ~75° tilt of 4E10’s helical epitope on gp41, both measured from the membrane surface (Figures 4A and 4B; Supplemental Information for model preparation). Therefore, the orientation of 4E10 relative to the lipid bilayer and to the MPER depicted in the model was based on its orientation with respect to the lipids and MPER epitope observed in our crystal structures and not on the trimeric gp41 transmembrane model built on PDB 2MOM template (Rout et al., 2014), which was primarily introduced into the model to anchor the MPER to the lipid bilayer. Considering the high density of lipid head groups in the membrane in the vicinity of 4E10, it is likely that additional interactions might occur besides those observed in our crystal structures (Figure 4B).

Neutralizing antibody 2F5 recognizes an epitope (residues 659–669) upstream of the 4E10 epitope. Residues S25GFSLS30 of CDRH1 in 2F5 are similar in sequence and conformation to CDRH1 in 4E10 (S25GGSFS30; Figure 1B and Figure 4C); the side chains of the two non-conserved residues point toward the Fab interior, and away from the lipid binding sites. CDRH3 in 2F5 is four residues longer than in 4E10 so that nine residues (99(H)-100G(H)) at the 2F5 CDRH3 tip protrude from the combining site (Figure 4C) and might interact with lipid acyl chains via Phe100B(H), Gly100C(H), Val100D(H), whereas its CDRH1 would interact with the lipid head groups, as also suggested by Julien et al. (2008).

In neutralizing antibody 10E8, substantial differences are observed in CDRH1 and CDRH3 compared to 4E10. 10E8 CDRH1 (SGFDFD; Figure 4D) contains three different residues (Phe27(H), Asp28(H), and Asp30(H)) compared to 4E10 (SGGSFS). To accommodate a PO4 group in CDRH1 site 1, a conformational change involving the 10E8 aspartate residues would be required to overcome steric hindrance. Unlike 4E10 and 2F5 where CDRH3 mainly interacts with the heavy chain, CDRH3 of 10E8 is pinned to the light chain by hydrophobic interactions (Figure 4D). This organization creates a crevice delimited on one side by CDRH1 and CDRH2 and on the other side by CDRH3 and the light-chain CDRs. Thus, a CDRH1-CDRH3 binding site for lipids as in 4E10 could not be recapitulated, as the tip of CDRH3 in 10E8 is located about 28 Å from CDRH1 (Figure 4D). Considering the position of the lipids relative to the MPER(671-683KKK) peptide in 4E10, and that 10E8 and 4E10 bind to the same helical epitope in gp41, we could roughly model the 10E8 regions that would interact with the membrane (Figure 4E). Therefore, superimposing the 10E8-MPER(RRR656-683RRR) (PDB 4G6F; Huang et al., 2012) with 4E10-MPER(671-683KKK) using the Cα atoms of shared peptide residues 671–683 (Figure 4E), 10E8 would approach the membrane via its CDRL1, CDRL2, and CDRH3 loops. CDRL1 and CDRL2 seemed poised to interact with the lipid head groups, and the hydrophobic residues at the tip of CDRH3 (Phe100A(H), Trp100B(H), Ser100C(H), Gly100D(H), Tyr100E(H)) would insert into the lipid tail region of the membrane. Although initially 10E8 is thought to not bind lipids (Huang et al., 2012), Chen et al. (2014) recently reported that 10E8 binds membranes rich in cholesterol possibly via Phe100A(H) and Trp100B(H), consistent with the angle of approach that we have proposed (Figure 4E). These findings indicated that the viral membrane together with the MPER forms a composite epitope for the MPER antibodies and that the 4E10’s epitope on gp41 is oriented upright with respect to the HIV membrane during 4E10’s binding.

Structural Model of Cardiolipin Binding to 4E10 and Implications for 2F5 and 10E8

To gain insight into cardiolipin binding to 4E10, we modeled a putative cardiolipin binding site based on the crystal structures of the 4E10-06:0 PA and 4E10-gp41 peptide-glycerol-3-phosphate complexes. Cardiolipin (diphosphatidylglycerol), consists of two PA molecules linked together by a glycerol bridge (Table 1). The phosphate atoms of the two 06:0 PA at CDRH1 sites 1 and 2 were located at the appropriate distance (7.6 Å) that can be connected by a glycerol bridge as in cardiolipin (Figure 2C). By superposing the Fabs of these two structures (Figure 1B and Figure 2C), the glycerol of glycerol-3-PO4 was oriented such that it spans the phosphates situated at sites 1 and 2 of CDRH1 (Figure 4F). Therefore, our modeling suggested that the binding region for the cardiolipin head group was Ser25(H)-Ser30(H) (SGGSFS) of CDRH1 (Figure 4F) with its tail anchored by CDRH3 Trp100(H)-Trp100B(H).

Some studies suggest that 2F5 also binds to cardiolipin, although with substantially lower affinity than 4E10 (Alam et al., 2007; Haynes et al., 2005), but other studies do not observe measurable binding (Matyas et al., 2009; Singh et al., 2011). Although CDRH1 is similar in 4E10 and 2F5, its flexibility in 2F5 is decreased due to Phe27(H) compared to Gly27(H) in 4E10. Cardiolipin binding is not observed with 10E8 (Chen et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2012). While some lipids like PA might bind 10E8, lack of cardiolipin binding was supported by our model as a glycerol bridge linking the two PA sites would clash with CDRL2 (Figure 4E). Our model suggested that CDRH1 of 4E10 might be involved in cardiolipin binding unlike 10E8.

Non-specific Ligand Binding

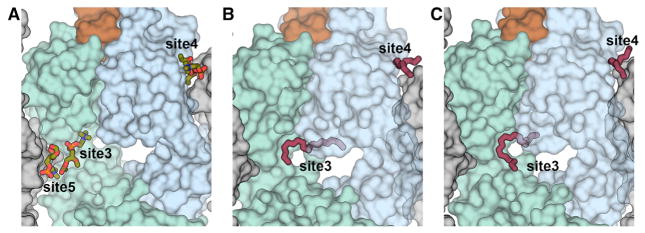

Out of all lipids tested (Table 1), some bound to a region of unknown biological relevance on the 4E10 Fab. Cryoprotection of 4E10 Fab-peptide crystals with the very short phosphatidylcholine, 03:0 PC, revealed four other lipid binding sites (sites 3–6), three of which (sites 4–6) were not considered biologically relevant as they were located in the Fab constant region (site 6) or at packing interfaces between symmetry-related molecules (sites 4 and 5; Figure 5A). The phosphocholine of 03:0 PC at site 3 was situated in the Fab elbow region in a hydrophobic cavity formed between conserved framework residues of the heavy and light chains (Figures S6A and S6B). Density for long tubular chains also appeared in this cavity (Figures 5B and 5C) in nearly all glycero-phospholipid and sphingolipid cryoprotected crystal structures (Table S2), as well as in co-crystal structures with 06:0 PA and 06:0 PG (Table S3), indicating that these ligands make hydrophobic contacts to the Fab main-chain (Figures S6C, S6D, S6E and S6F). Because both lipids and polyethylene glycol (PEG) were present in the crystallization conditions, it was not possible to distinguish between PEG and lipid tails occupying this site 3 cavity and, therefore, we assigned this density as UNL (unknown ligand). Although 4E10 could clearly bind hydrophobic molecules in site 3, this site was likely not biologically relevant (see Figures S6C and S6E), although it might explain binding to a large panel of lipids in solution.

Figure 5. Non-specific Ligand Binding to 4E10.

(A) Location of 03:0 PC binding sites in 4E10 Fab-peptide-03:0 PC complex (cyan light chain, blue heavy chain, brown peptide). Neighboring Fab molecules are shown as gray surfaces. The three 03:0 PCs (green sticks) bound to the variable region of the Fab at sites 3, 4, and 5 are shown, but the fourth 03:0 PC bound in the constant region is omitted.

(B and C) illustrate the binding of a ligand (pink sticks; sites 3 and 4) in the 4E10-MPER(671-683KKK) structure cryoprotected with 02:0 SM (d18:1/2:0) and 08:0 PA, respectively. The ligand (either PEG or lipid hydrophobic tails) (Table S2) was assigned as “UNL” for unknown ligand. See also Figure S6 and Table S2.

DISCUSSION

Over the last few years, significant efforts have been made to induce strong neutralizing antibody responses against the highly conserved MPER region (Dennison et al., 2011; Serrano et al., 2014), but without success. Due to its binding to cardiolipin (an exclusive mitochondrial membrane lipid; van Meer et al., 2008) and other glycero-phospholipids (Matyas et al., 2009), 4E10 was suggested to be a polyspecific, anti-phospholipid antibody of infectious, non-pathogenic origin (Haynes et al., 2005), and its passive infusion in people is well tolerated, despite an observed increase in the partial thromboplastin time (Mehandru et al., 2007; Vcelar et al., 2007). It has been proposed that 4E10-like antibodies are produced only rarely, because autoreactive B cells are either removed from the repertoire or become tolerant to self-antigens (Alam et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2013; Doyle-Cooper et al., 2013; Haynes et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2013). The reactivity profiles of 4E10, when assessed on larger panels of autoantigens, clearly differ from pathogenic autoantibodies (plasma protein dependent, e.g., β2GPI, prothrombin, etc.) involved in antiphospholipid antibody syndrome and lupus (Scherer et al., 2007; Singh et al., 2011). Antiphospholipid antibodies that directly bind glycero-phospholipids (B2GPI independent, as for 4E10) and are associated with infection, do not produce complications, and decrease once the infection is cured (Asherson and Cervera, 2003; Sène et al., 2009). Although the tolerance mechanism was evoked to explain the failure of MPER immunogen designs to induce neutralizing responses, another plausible explanation is that the MPER orientation differs from those on the virus or that the lipid component of the epitope was absent (Chen et al., 2014; Scherer et al., 2010).

Here, we investigated the interaction of 4E10 with the nine strongest lipid binders (Matyas et al., 2009) by X-ray crystallography. Only phosphatidic acid, phosphatidylglycerol, and glycerol-phosphate were identified in the crystal structures proximal to the antibody combining site in locations that appear to be biologically relevant. Our data showed that the 4E10 CDRH1 contributed residues for binding lipid head groups, while Trp100(H), Gly100A(H), Trp100B(H) at the CDRH3 tip interacted with the lipid tail. As CDRH3 reorganizes to accommodate the lipid hydrophobic tail, Leu100C(H) and Gly100D(H) come into close contact with MPER Trp680(P). Thus, to simultaneously accommodate both components of its epitope (lipids and MPER peptide), a slight reorganization of its flexible CDRH3 loop is necessary.

Studies of the HIV-1 lipodome have identified the lipids that are most abundant on the HIV membrane (Aloia et al., 1993; Lorizate et al., 2013). PA and PG, which bind best to 4E10, are among the less abundant species within the HIV-1 envelope, although PG levels increase on HIV-1 membranes arising from certain cell types (Lorizate et al., 2013). In the plasma membrane, both PA and PG are only transiently present and located mainly in the inner leaflet. In normal phospholipid metabolism, cellular phosphatidic acid is rapidly converted to diacylglycerol or lysophosphatidic acid (Cazzolli et al., 2006) and PG is located mostly in lung surfactants and mitochondrial and microsomal membranes (Morita and Terada, 2015). During HIV-1 infection, activated phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase D resulting from CCR5 coreceptor activation cleaves the membrane-abundant PC into choline and PA (Paruch et al., 2007). The increase in PA in plasma membrane coupled with the scramblase activity that translocates glycero-phospholipids in apoptotic cells (e.g., in HIV-1 infected cells), might result in exposure of PA and PG on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane for capture on HIV envelopes during the budding process. Therefore, MPER-grafted immunogens (in the orientation guided by our structural data) embedded in liposomes that include PA and PG, which only fleetingly appear on the outer leaflet, are more likely to elicit MPER-like antibodies that bind both protein and lipid components. Liposomes containing only the major components of the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane, like PC, SM, and cholesterol, might be less likely to elicit antibodies that react with lipid components due to tolerance mechanisms. Also, the shift toward the fully saturated acyl chains and monounsaturated species observed for HIV-1 membranes compared to plasma membranes (Lorizate et al., 2013) should be taken into account in liposome formulations.

2F5 shows a similar, but likely a more rigid, CDRH1 than 4E10 and its protruding hydrophobic CDRH3 might interact with the hydrophobic tails of CDRH1-bound lipids. In contrast, for 10E8, the CDRH1-CDRH3 site for lipid binding is not formed due to its CDRH3 being about 28 Å from CDRH1. Instead, 10E8 most likely interacts with the viral membrane via CDRL1, CDRL2, and CDRH3, with the first two loops potentially accommodating the lipid head groups and CDRH3 inserting into the membrane. Although 10E8 does not bind PC-PS and PC-CL liposomes (Huang et al., 2012), its preference for cholesterol-rich membranes (Chen et al., 2014) might be explained by the small size of the cholesterol head group represented by a hydroxyl, which would facilitate insertion of the hydrophobic CDRH3 into the apolar region of the membrane.

Our model for 4E10-cardiolipin binding was based on two PA head groups and a glycerol-phosphate bound to the CDRH1 region. Our structural analysis suggested that CL binding to 2F5 is plausible, but not for 10E8 because its glycerol bridge would overlap with CDRL2.

The same gp41 epitope targeted by 4E10 is also targeted by the non-autoreactive antibody 10E8. To date, MPER-based immunogens have led only to non-neutralizing antibodies (Montero et al., 2008). The epitopes, as presented in these immunogens, are likely not in the orientation presented on the HIV-1 surface, which may account for their failure to elicit neutralizing antibodies (autoreactive or otherwise). Our work here revealed how the antibody and the MPER epitope are oriented with respect to the viral membrane during antibody engagement that should help guide immunogen design so as to present the MPER in the correct orientation with respect to the membrane (i.e., in liposomes, chimeric viruses that expose MPER) and with the right lipid composition. Such immunogens are more likely to induce neutralizing responses, which can be of non-autoreactive origin like 10E8, and hopefully resolve attempts to elicit neutralizing antibodies against the MPER region of HIV-1 by vaccination.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

All lipids (Table 1) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, except rac-glycerol-1-PO4, sn-glycerol-3-PO4, cholesterol (Sigma-Aldrich), and 1-IP1 and 1,4,5-IP3 (Cayman Chemical). The pDR12 mammalian expression vector encoding 4E10 IgG1(κ) was provided by Dennis Burton and the MPER(671-683KKK) mimetic variants by Philip Dawson.

4E10 Fab Purification

4E10 IgG1(κ) was expressed in FreeStyle 293S cells (Invitrogen) as described by Scherer et al. (2010). IgG was purified using rProtein A Sepharose Fast Flow (GE Healthcare) and digested by papain to obtain Fab, which was purified as described by Cardoso et al. (2007) and stored in 20 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.5) at 10 mg/ml.

Crystallization of 4E10 Fab-MPER(671-683KKK) and 4E10 Fab-Lipids Complexes

Cryoprotection of 4E10 Fab-MPER Peptide with Pure Lipids or Lipid Head Groups

4E10 Fab was incubated overnight at 4°C with MPER peptides (sequence: N671WFDITNWLWYIK683), either as MPER(671-683KKK) (PDB 2FX7; Cardoso et al., 2007), MPER(671-683KKK)*08062, or MPER(671-683KKK)*0902 (Ingale et al. (2010) in a 1:5 protein:peptide molar ratio. Crystals of 4E10Fab-MPER peptide complex grew from 1:1 protein:reservoir sitting drops equilibrated against 18%–24% PEG 8000, 0.2 M sodium acetate pH 5.5, 0.2 M sodium thiocyanate. The crystals were cryoprotected with individual lipids or lipid head groups (Table 1; Table S2) solubilized in mother liquor stock solution (20% PEG 8000, 0.2 M sodium acetate pH 5.5, 0.2 M sodium thiocyanate). The cryoprotected crystals were flash cooled in liquid nitrogen.

Co-crystallization of 4E10 with Pure Lipids

Water-soluble short-chain glycero-phospholipids (06:0 PA, 06:0 PG, 0.6:0 PC and 06:0 PE; Table 1, Table S3), were each solubilized to 15 mM in 20 mM Na Acetate (pH 5.5) then mixed with 4E10 Fab (28 mg/ml in the same buffer) to a final concentration of about 10 mg/ml Fab and 10 mM lipid. Initial crystal screening was performed with the JCSG-IAVI-TSRI CrystalMation robot (Rigaku). The crystals were optimized by seeding using the Oryx automatic protein crystallization system (Douglas Instruments) or manually. The reservoir conditions and cryoprotectant are shown in Table S3.

Data Collection, Structure Determination, and Refinement

Data collection was performed at the Advanced Photon Source 23-ID beam lines or at SSRL beam lines 12-2 or 11-1 (see Tables S2 and S3). The diffraction data were processed with HKL-2000 (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997) or XDS (Kabsch, 2010). About 60–80 crystals of 4E10-06:0 PG were screened, but most diffracted to around 6–7 Å with rare cases of 4–5 Å. Moderate resolution diffraction was observed for the other 4E10 Fab-lipid co-crystal complexes, where 2.7–2.95 Å data were obtained (Table S3). Molecular replacement (MR) was performed with Phaser (McCoy et al., 2007) using 4E10 Fab from PDB 2FX7 (Cardoso et al., 2007) as the MR model without MPER peptide and solvent molecules. Rigid body refinement was performed with Phenix (Adams et al., 2010) and model rebuilding in Coot (Emsley et al., 2010). Details of refinement strategies are outlined in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures. Final statistics are in Tables S2 and S3. Images were generated with Py-MOL (The PyMOL molecular graphics system).

Viral Membrane Model Assembly with CHARMM

A structural model comprising the MPER-transmembrane region of gp41 was modeled based on our crystal structures and embedded into the lipid bilayer using CHARMM-GUI (see details in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures), followed by a MD simulation for 50 ns with the CHARMM force field (Brooks et al., 2009) to study the stability of the model in solution.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

4E10 epitope includes membrane lipids as well as the HIV-1 gp41 region

4E10 CDRH1 and CDRH3 interact with the lipid head and acyl tails, respectively

MPER epitope is likely oriented perpendicular to the HIV membrane upon 4E10 binding

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Stephen Connelly and Marc Elsliger for discussions, Dr. Marc Deller and Henry Tien for technical support with crystallization robots, and Drs. Jean-Philippe Julien and Leopold Kong for kindly providing crystals of PGT135 and PGT145 antibodies for control experiments. This work was supported by NIH grants R01 AI084817 to I.A.W. and Scripps CHAVI-ID (UM1 AI100663), and partially funded by IAVI with the generous support of USAID, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; a full list of IAVI donors is available at www.iavi.org. Use of the 23-ID sector at Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy. Portions of this research were carried out at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, a Directorate of SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, and an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science by Stanford University. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by NIH NIGMS, (including P41GM103393). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIGMS, NIAID, NIH, USAID or the US Government. This is publication 29027 from The Scripps Research Institute.

Footnotes

ACCESSION NUMBERS

The atomic coordinates and structure factors of 4E10 structures have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, with accession codes as follows: 4XCN, 4XBG, 4XCY, 4XCC, 4XCE, and 4XBP, for cocrystals of 4E10 Fab-06:0 PA (2.9 Å), 4E10 Fab-06:0 PA (2.73 Å), 4E10 Fab-06:0 PG, 4E10 Fab-06:0 PC (I422 space group), 4E10 Fab-06:0 PC (C2 space group), and 4E10 Fab-06:0 PE, respectively, and 4XC1, 4XC3, 4XCF, 4XAW, 4XBE for 4E10-MPER peptide variants cryoprotected with sn-glycerol-3-PO4, rac-glycerol-1-PO4, 03:0 PC, 08:0 PA, and 02:0 SM(d18:1/2:0), respectively.

Supplemental Information includes six figures, three tables, and Supplemental Experimental Procedures and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2015.12.001.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.I. conducted the X-ray crystallographic studies, protein purification, crystallization, and molecular modeling. A.S. performed molecular modeling and MD simulation. A.I., R.L.S., A.S., and I.A.W. analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript.

References

- Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkóczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam SM, McAdams M, Boren D, Rak M, Scearce RM, Gao F, Camacho ZT, Gewirth D, Kelsoe G, Chen P, Haynes BF. The role of antibody polyspecificity and lipid reactivity in binding of broadly neutralizing anti-HIV-1 envelope human monoclonal antibodies 2F5 and 4E10 to glycoprotein 41 membrane proximal envelope epitopes. J Immunol. 2007;178:4424–4435. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam SM, Morelli M, Dennison SM, Liao HX, Zhang R, Xia SM, Rits-Volloch S, Sun L, Harrison SC, Haynes BF, Chen B. Role of HIV membrane in neutralization by two broadly neutralizing antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:20234–20239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908713106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloia RC, Tian H, Jensen FC. Lipid composition and fluidity of the human immunodeficiency virus envelope and host cell plasma membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5181–5185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asherson RA, Cervera R. Antiphospholipid antibodies and infections. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:388–393. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.5.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks BR, Brooks CL, 3rd, Mackerell AD, Jr, Nilsson L, Petrella RJ, Roux B, Won Y, Archontis G, Bartels C, Boresch S, et al. CHARMM: the biomolecular simulation program. J Comput Chem. 2009;30:1545–1614. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunel FM, Zwick MB, Cardoso RM, Nelson JD, Wilson IA, Burton DR, Dawson PE. Structure-function analysis of the epitope for 4E10, a broadly neutralizing human immunodeficiency virus type 1 antibody. J Virol. 2006;80:1680–1687. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.4.1680-1687.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzon V, Natrajan G, Schibli D, Campelo F, Kozlov MM, Weissenhorn W. Crystal structure of HIV-1 gp41 including both fusion peptide and membrane proximal external regions. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000880. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso RM, Zwick MB, Stanfield RL, Kunert R, Binley JM, Katinger H, Burton DR, Wilson IA. Broadly neutralizing anti-HIV antibody 4E10 recognizes a helical conformation of a highly conserved fusion-associated motif in gp41. Immunity. 2005;22:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso RM, Brunel FM, Ferguson S, Zwick M, Burton DR, Dawson PE, Wilson IA. Structural basis of enhanced binding of extended and helically constrained peptide epitopes of the broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibody 4E10. J Mol Biol. 2007;365:1533–1544. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.10.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazzolli R, Shemon AN, Fang MQ, Hughes WE. Phospholipid signalling through phospholipase D and phosphatidic acid. IUBMB Life. 2006;58:457–461. doi: 10.1080/15216540600871142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Zhang J, Hwang KK, Bouton-Verville H, Xia SM, Newman A, Ouyang YB, Haynes BF, Verkoczy L. Common tolerance mechanisms, but distinct cross-reactivities associated with gp41 and lipids, limit production of HIV-1 broad neutralizing antibodies 2F5 and 4E10. J Immunol. 2013;191:1260–1275. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Frey G, Peng H, Rits-Volloch S, Garrity J, Seaman MS, Chen B. Mechanism of HIV-1 neutralization by antibodies targeting a membrane-proximal region of gp41. J Virol. 2014;88:1249–1258. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02664-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien MP, Jiang S, Chang DK. The function of coreceptor as a basis for the kinetic dissection of HIV type 1 envelope protein-mediated cell fusion. FASEB J. 2008;22:1179–1192. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9576com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun TW, Fauci AS. HIV reservoirs: pathogenesis and obstacles to viral eradication and cure. AIDS. 2012;26:1261–1268. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328353f3f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennison SM, Sutherland LL, Jaeger FH, Anasti KM, Parks R, Stewart S, Bowman C, Xia SM, Zhang R, Shen X, et al. Induction of antibodies in rhesus macaques that recognize a fusion-intermediate conformation of HIV-1 gp41. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e27824. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle-Cooper C, Hudson KE, Cooper AB, Ota T, Skog P, Dawson PE, Zwick MB, Schief WR, Burton DR, Nemazee D. Immune tolerance negatively regulates B cells in knock-in mice expressing broadly neutralizing HIV antibody 4E10. J Immunol. 2013;191:3186–3191. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finton KA, Larimore K, Larman HB, Friend D, Correnti C, Rupert PB, Elledge SJ, Greenberg PD, Strong RK. Autoreactivity and exceptional CDR plasticity (but not unusual polyspecificity) hinder elicitation of the anti-HIV antibody 4E10. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003639. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey G, Peng H, Rits-Volloch S, Morelli M, Cheng Y, Chen B. A fusion-intermediate state of HIV-1 gp41 targeted by broadly neutralizing antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3739–3744. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800255105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison SC. Viral membrane fusion. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:690–698. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes BF, Fleming J, St Clair EW, Katinger H, Stiegler G, Kunert R, Robinson J, Scearce RM, Plonk K, Staats HF, et al. Cardiolipin polyspecific autoreactivity in two broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibodies. Science. 2005;308:1906–1908. doi: 10.1126/science.1111781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Ofek G, Laub L, Louder MK, Doria-Rose NA, Longo NS, Imamichi H, Bailer RT, Chakrabarti B, Sharma SK, et al. Broad and potent neutralization of HIV-1 by a gp41-specific human antibody. Nature. 2012;491:406–412. doi: 10.1038/nature11544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingale S, Gach JS, Zwick MB, Dawson PE. Synthesis and analysis of the membrane proximal external region epitopes of HIV-1. J Pept Sci. 2010;16:716–722. doi: 10.1002/psc.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julien JP, Bryson S, Nieva JL, Pai EF. Structural details of HIV-1 recognition by the broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibody 2F5: epitope conformation, antigen-recognition loop mobility, and anion-binding site. J Mol Biol. 2008;384:377–392. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julien JP, Cupo A, Sok D, Stanfield RL, Lyumkis D, Deller MC, Klasse PJ, Burton DR, Sanders RW, Moore JP, et al. Crystal structure of a soluble cleaved HIV-1 envelope trimer. Science. 2013;342:1477–1483. doi: 10.1126/science.1245625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorizate M, Sachsenheimer T, Glass B, Habermann A, Gerl MJ, Kräusslich HG, Brügger B. Comparative lipidomics analysis of HIV-1 particles and their producer cell membrane in different cell lines. Cell Microbiol. 2013;15:292–304. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyumkis D, Julien JP, de Val N, Cupo A, Potter CS, Klasse PJ, Burton DR, Sanders RW, Moore JP, Carragher B, et al. Cryo-EM structure of a fully glycosylated soluble cleaved HIV-1 envelope trimer. Science. 2013;342:1484–1490. doi: 10.1126/science.1245627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matyas GR, Beck Z, Karasavvas N, Alving CR. Lipid binding properties of 4E10, 2F5, and WR304 monoclonal antibodies that neutralize HIV-1. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:660–665. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Cryst. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehandru S, Vcelar B, Wrin T, Stiegler G, Joos B, Mohri H, Boden D, Galovich J, Tenner-Racz K, Racz P, et al. Adjunctive passive immunotherapy in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected individuals treated with antiviral therapy during acute and early infection. J Virol. 2007;81:11016–11031. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01340-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero M, van Houten NE, Wang X, Scott JK. The membrane-proximal external region of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope: dominant site of antibody neutralization and target for vaccine design. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2008;72:54–84. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00020-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita SY, Terada T. Enzymatic measurement of phosphatidyl-glycerol and cardiolipin in cultured cells and mitochondria. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11737. doi: 10.1038/srep11737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofek G, Tang M, Sambor A, Katinger H, Mascola JR, Wyatt R, Kwong PD. Structure and mechanistic analysis of the anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 antibody 2F5 in complex with its gp41 epitope. J Virol. 2004;78:10724–10737. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10724-10737.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pancera M, Zhou T, Druz A, Georgiev IS, Soto C, Gorman J, Huang J, Acharya P, Chuang GY, Ofek G, et al. Structure and immune recognition of trimeric pre-fusion HIV-1 Env. Nature. 2014;514:455–461. doi: 10.1038/nature13808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paruch S, Heinis M, Lemay J, Hoeffel G, Marañón C, Hosmalin A, Périanin A. CCR5 signaling through phospholipase D involves p44/42 MAP-kinases and promotes HIV-1 LTR-directed gene expression. FASEB J. 2007;21:4038–4046. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7325com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathinakumar R, Dutta M, Zhu P, Johnson WE, Roux KH. Binding of anti-membrane-proximal gp41 monoclonal antibodies to CD4-liganded and -unliganded human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and simian immunodeficiency virus virions. J Virol. 2012;86:1820–1831. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05489-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rout AK, Strub MP, Piszczek G, Tjandra N. Structure of transmembrane domain of lysosome-associated membrane protein type 2a (LAMP-2A) reveals key features for substrate specificity in chaperone-mediated autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:35111–35123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.609446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzwedel K, West JT, Hunter E. A conserved tryptophan-rich motif in the membrane-proximal region of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 ectodomain is important for Env-mediated fusion and virus infectivity. J Virol. 1999;73:2469–2480. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.2469-2480.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer EM, Zwick MB, Teyton L, Burton DR. Difficulties in eliciting broadly neutralizing anti-HIV antibodies are not explained by cardiolipin autoreactivity. AIDS. 2007;21:2131–2139. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282a4a632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer EM, Leaman DP, Zwick MB, McMichael AJ, Burton DR. Aromatic residues at the edge of the antibody combining site facilitate viral glycoprotein recognition through membrane interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:1529–1534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909680107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sène D, Piette JC, Cacoub P. Antiphospholipid antibodies, antiphospholipid syndrome and viral infections. Rev Med Interne. 2009;30:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2008.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano S, Araujo A, Apellániz B, Bryson S, Carravilla P, de la Arada I, Huarte N, Rujas E, Pai EF, Arrondo JL, et al. Structure and immunogenicity of a peptide vaccine, including the complete HIV-1 gp41 2F5 epitope: implications for antibody recognition mechanism and immunogen design. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:6565–6580. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.527747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh H, Henry KA, Wu SS, Chruscinski A, Utz PJ, Scott JK. Reactivity profiles of broadly neutralizing anti-HIV-1 antibodies are distinct from those of pathogenic autoantibodies. AIDS. 2011;25:1247–1257. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834785cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun ZY, Oh KJ, Kim M, Yu J, Brusic V, Song L, Qiao Z, Wang JH, Wagner G, Reinherz EL. HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibody extracts its epitope from a kinked gp41 ectodomain region on the viral membrane. Immunity. 2008;28:52–63. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundquist WI, Kräusslich HG. HIV-1 assembly, budding, and maturation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a006924. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The PyMOL molecular graphics system, version 1.3. Schrödinger, LLC; [Google Scholar]

- Tran EE, Borgnia MJ, Kuybeda O, Schauder DM, Bartesaghi A, Frank GA, Sapiro G, Milne JL, Subramaniam S. Structural mechanism of trimeric HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein activation. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002797. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Meer G, Voelker DR, Feigenson GW. Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:112–124. doi: 10.1038/nrm2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vcelar B, Stiegler G, Wolf HM, Muntean W, Leschnik B, Mehandru S, Markowitz M, Armbruster C, Kunert R, Eibl MM, Katinger H. Reassessment of autoreactivity of the broadly neutralizing HIV antibodies 4E10 and 2F5 and retrospective analysis of clinical safety data. AIDS. 2007;21:2161–2170. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328285da15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker LM, Huber M, Doores KJ, Falkowska E, Pejchal R, Julien JP, Wang SK, Ramos A, Chan-Hui PY, Moyle M, et al. Broad neutralization coverage of HIV by multiple highly potent antibodies. Nature. 2011;477:466–470. doi: 10.1038/nature10373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Holl TM, Liu Y, Li Y, Lu X, Nicely NI, Kepler TB, Alam SM, Liao HX, Cain DW, et al. Identification of autoantigens recognized by the 2F5 and 4E10 broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibodies. J Exp Med. 2013;210:241–256. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwick MB. The membrane-proximal external region of HIV-1 gp41: a vaccine target worth exploring. AIDS. 2005;19:1725–1737. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000189850.83322.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwick MB, Labrijn AF, Wang M, Spenlehauer C, Saphire EO, Binley JM, Moore JP, Stiegler G, Katinger H, Burton DR, Parren PW. Broadly neutralizing antibodies targeted to the membrane-proximal external region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 glycoprotein gp41. J Virol. 2001;75:10892–10905. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.22.10892-10905.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.