Abstract.

Contrast enhancement is a key component of computed tomography (CT) imaging and offers opportunities for optimization. The design and optimization of techniques, however, require orchestration with the scan parameters and, further, a methodology to relate contrast enhancement and injection function. We used such a methodology to develop a method, the analytical inverse method, to predict the required injection function to achieve a desired contrast enhancement in a given organ by incorporation of a physiologically based compartmental model. The method was evaluated across 32 different target contrast enhancement functions for aorta, kidney, stomach, small intestine, and liver. The results exhibited that the analytical inverse method offers accurate performance with error in the range of 10% deviation between the predicted and desired organ enhancement curves. However, this method is incapable of predicting the injection function based on the liver enhancement. The findings of this study can be useful in optimizing contrast medium injection function as well as scan timing to provide more consistency in the way contrast-enhanced CT examinations are performed. To our knowledge, this work is one of the first attempts to predict the contrast material injection function for a desired organ enhancement curve.

Keywords: computed tomography, contrast material, compartmental model, contrast enhanced, patient specific

1. Introduction

In clinical practice, contrast material is widely administered to improve image quality and diagnostic sensitivity.1 Currently, over 60% of total computed tomography (CT) examination routines performed in the United States are contrast enhanced.2 However, different institutions have different procedures regarding contrast enhancement. For example, some institutions alter the amount of contrast agent based on patient size and age, while others do not. Overall, there is not a consistent, systematic administration technique across different clinical practices. This leads to inconsistent enhancement across different patients.3–5 Without factoring in patient-specific attributes, contrast-enhanced CT examinations cannot be fully optimized in terms of scan timing, image quality, or radiation dose.6

The design and optimization of new contrast material administration techniques properly orchestrated with the scan parameters (e.g., scan timing) requires an established relationship between contrast enhancement and the injection function. Knowing the dynamics of contrast material distribution, we can design a method to model the injection protocols for different patients based on the desired contrast enhancements. Such a method allows us to build toward an integrated optimization of contrast medium dose, radiation dose, image quality, and patient-specific contrast administration protocols together.

The purpose of this study was to develop and evaluate a strategy to determine the required contrast material injection function to achieve a desired contrast enhancement in the aorta, kidneys, stomach, small intestine, and liver. Two methods were developed, analytical inverse and iterative stripping, to predict the required contrast medium injection function to achieve a desired contrast enhancement curve as a function of time in specific organs by incorporation of a physiologically based compartmental model of dynamics of contrast material distribution (forward model). Our methods were evaluated using a library of computational phantoms. To the best of our knowledge of literature, our work is the first approach to predict the right injection function based on the desired contrast enhancement in a given organ in the context of an individual patient and as a function of time.

2. Methods

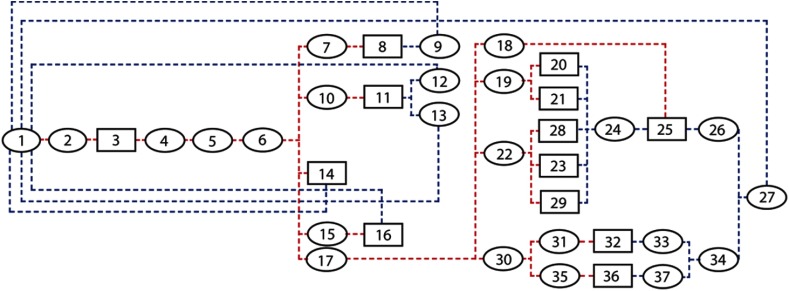

To describe the dynamics of contrast material within the human body, a computer-based physiologic model of the cardiovascular system has been previously developed (Fig. 1).2,6–8 The model is composed of a network of compartmentalized heart, vessels, and organs. This compartmental model (forward model) integrates multiple regulatory factors that govern contrast perfusion, such as weight, height, age, gender, cardiac output, and blood volume, by incorporating computational pharmacokinetics and known available physiologic data. The enhanced blood is assumed to be a uniform mixture of blood and contrast material. As this mixture reaches a compartment, it is distributed through it and is subsequently washed out. Within this process, the flow rate and concentration of the contrast material within the blood is changing. A mass balance equation described by Fick’s law of diffusion is applied to each compartment as part of an integrated system.7,9 In our previous work, the concentration of contrast material in each organ was calculated by solving a series of differential equations defining the forward model. The model was extended to a library of retrospectively chosen patients representing a wide range of body types and age groups of adult males and females extended cardiac-torso (XCAT) models (35 male, 23 female, mean age 51.5 years, mean weight 80.2 kg).10–12 To construct the patient-specific forward model for each phantom, the known organ volumes were extracted from each specific XCAT model and used to adjust the entire regional blood volumes of the organs (including intravascular, extracellular, and intracellular spaces) in the standard forward model.2 In our current work, two techniques were used to predict the injection function to provide a targeted enhancement curve of an organ or vessel across different patient models.

Fig. 1.

The physiologically based compartmental model used for simulating the pharmacokinetics of contrast medium via the cardiovascular system through the body. The model includes 38 compartments: each ellipse represents a vessel compartment and each box represents an organ (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Estimated blood distribution, blood flow rate, and capillary volumes used in the standard forward model. The compartments are numbered in the order that they appear in Fig. 1. In our compartmental model, the heart was constructed of three separate compartments: left heart, right heart, and heart muscle. Note that due to the negligible amount of perfusion occurring in the left and right heart, they were treated as vessel compartments. The table includes the organs’ names, and the vessels are named with their compartment numbers (except the aorta).

| Compartment | Type | BFR (ml/s) | IVV (ml) | ECV (ml) | Compartment | Type | BFR (ml/s) | IVV (ml) | ECV (ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Right heart | Vessel | 29.0 | 180 | 0 | 20. S. intestine | Organ | 15.6 | 20 | 322 |

| 2. Pulmonary artery | Vessel | 108.3 | 130 | 0 | 21. L. intestine | Organ | 15.6 | 14 | 218 |

| 3. Lung P | Organ | 108.3 | 150 | 144 | 22. Celiac artery | Vessel | 8.2 | 20 | 0 |

| 4. Pulmonary vein | Vessel | 108.3 | 160 | 0 | 23. Stomach | Organ | 8.25 | 10 | 62 |

| 5. Left heart | Vessel | 108.3 | 180 | 0 | 24. Portal vein | Vessel | 23.8 | 100 | 0 |

| 6. Aorta | Vessel | 108.3 | 100 | 0 | 25. Liver | Organ | 7.5 | 71 | 524 |

| 7. Carotid artery | Vessel | 16.3 | 20 | 0 | 26. Renal vein | Vessel | 31.4 | 100 | 0 |

| 8. Head | Organ | 16.3 | 37 | 484 | 27. IVC | Vessel | 80.1 | 800 | 0 |

| 9. S. jugular vein | Vessel | 16.3 | 80 | 0 | 28. Pancreas | Organ | 8.25 | 2 | 12 |

| 10. Subclavian aorta | Vessel | 5.4 | 20 | 0 | 29. Spleen | Organ | 8.25 | 6 | 37 |

| 11. Up. extremity | Organ | 5.4 | 12 | 2751 | 30. Abdominal aorta | Vessel | 48.7 | 80 | 0 |

| 12. SVC | Vessel | 2.7 | 40 | 0 | 31. Renal artery | Vessel | 23.8 | 20 | 0 |

| 13. SVC | Vessel | 2.7 | 40 | 0 | 32. Kidney | Organ | 23.8 | 54 | 89 |

| 14. Heart muscle | Organ | 4.3 | 10 | 103 | 33. Renal vein | Vessel | 23.8 | 100 | 0 |

| 15. Bronchial artery | Vessel | 82.3 | 100 | 0 | 34. IVC | Vessel | 48.7 | 700 | 0 |

| 16. Lung NP | Organ | 2.2 | 5 | 144 | 35. Iliac artery | Vessel | 24.9 | 200 | 0 |

| 17. Descending aorta | Vessel | 80.2 | 100 | 0 | 36. Trunk/low ext | Organ | 24.9 | 57 | 11,002 |

| 18. Hepatic artery | Vessel | 7.5 | 20 | 0 | 37. Iliac vein | Vessel | 24.9 | 1000 | 0 |

| 19. Mesenteric artery | Vessel | 15.5 | 20 | 0 |

Note: BFR, blood flow rate; IVV, intravascular volume; ECV, extracellular volume; SVC, superior vena cava; IVC, inferior vena cava.

2.1. Analytical Inverse Method

For a given contrast enhancement function in a particular compartment (vessel or organ), the analytical inverse method was applied to calculate the required injection function as a function of time as described below. First, the proportional iodine concentration (IC) function was calculated from the given contrast enhancement. Depending on the compartment with the known IC, a specified path of interest (was selected), starting from the compartment to the injected vessel compartment. Second, for the path of interest, specified sets of differential equations were successively solved starting from the target organ back toward the first compartment (injected vessel). The differential equations were interpreted as Fick’s law description of the IC balance applied as

| (1) |

for a vessel compartment and as

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

for an organ compartment. In these equations, is the volume, is the blood flow rate, and are the input and output concentrations, is the mass of contrast medium, is the vascular membrane permeability, is the surface area, and, finally, is the time. The output of the final compartment or injected vessel was in the form of continuous functions. Finally, the injection function was created by converting the predicted function into a rectangular function based on the expected capability of common contrast injectors [Figs. 3(a) and 3(b)]. The height of the rectangular function was matched to the predicted function plateau and the width of the rectangular function was calculated by dividing the area under the curve by the plateau.

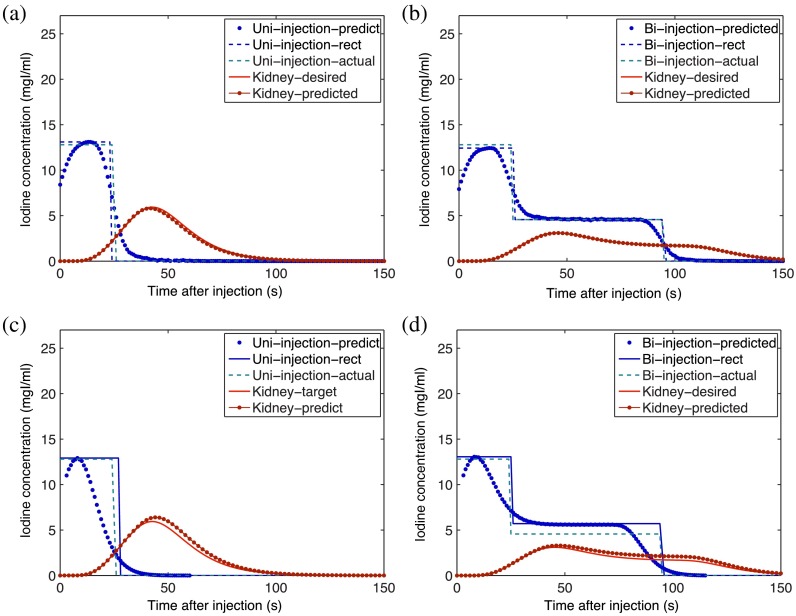

Fig. 3.

The enhancement curves calculated in the kidneys applying the analytical inverse [(a) and (b)] and the iterative stripping models [(c) and (d)] for a uniphasic (injection of 125 mL of contrast medium of IC at ) and a biphasic (injection of 50 mL of the same contrast medium at followed by 75 mL at ) injection protocol, respectively.

2.2. Iterative Stripping Method

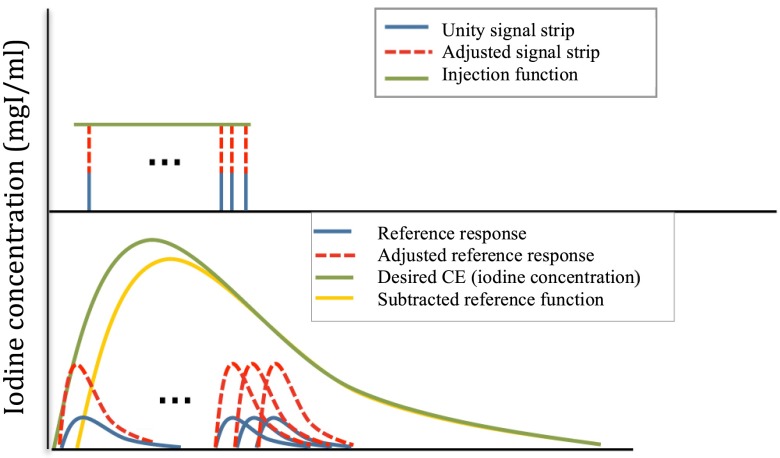

In the iterative stripping technique, the injection IC function (signal) was considered as deconvolution of the target IC (response).13–16 The iterative deconvolution technique assumes that the final target response is composed of the individual responses of a series of unit signals (strips). In this method, the reference response was calculated by applying our forward compartmental model to the first unity signal strip (input function). The reference response amplitude was then adjusted to the magnitude of the target concentration value at the corresponding identical time point by multiplying it by an adjustment factor. This adjustment factor was also applied to the unity signal strip. The adjusted reference response was subtracted from the target concentration function to determine the response function without the contribution of the first signal. This step-by-step procedure was then iteratively repeated through a series of signal strips at multiple time points and subtracted reference functions. The iterative process was stopped when the remainder of the subtracted function reached a negative value. Finally, the injection function was created by converting the estimated continuous function into a rectangular function (Fig. 2). Similarly to the first method, the width of the rectangular function was calculated by dividing the area under the curve by the estimated continuous function plateau.

Fig. 2.

Iterative stripping model. This figure summarizes the steps of the iterative stripping technique. The unity signal strip, adjusted signal strip, and predicted uniphasic injection function are shown at the top. The reference response, adjusted response functions, desired IC (calculated from the contrast enhancement), and subtracted reference functions are shown below.

2.3. Evaluation

For evaluation purposes, 32 different injection protocols composed of four different ICs, four different injection durations, and two injection bolus shapes (uniphasic and biphasic) were created. The uniphasic and biphasic injection protocols used for the evaluation are summarized in Table 2. The target desired organ enhancements () in the aorta, kidneys, stomach, small intestine, and liver were determined as the targeted enhancement functions. Using the analytical inverse and iterative stripping methods, the injection functions were predicted () from the targeted organ enhancement functions across all XCAT models. Applying the forward compartmental model on , the predicted organ enhancement () curves were then calculated. For both methods, the accuracy of the predicted organ enhancement results were evaluated and compared across different protocols. The evaluation steps were repeated across all the XCAT models used in this study.

Table 2.

Contrast material administration protocols. 32 different injection protocols composed of four different ICs, four different injection durations, and two injection bolus shapes (uniphasic and biphasic) were studied.

| IC (mgI/ml) | Volume (ml) | Injection duration (first phase) | Injection duration (second phase) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uniphasic | 300, 320, 350, 400 | 125 | 20, 25, 30, 35 | 0 |

| Biphasic | 300, 320, 350, 400 | 125 | 20, 25, 30, 35 | 75, 70, 65, 60 |

For comparison between the desired and predicted organ enhancement curves, three different error metrics were calculated and averaged across all the patients: (1) time-to-peak error (%), (2) peak value error (%), and (3) mean absolute error (MAE in %).17 The MAE was defined as

| (5) |

Error maps were created for the kidneys by calculating and using the errors across the entire uniphasic and biphasic protocols. Each error map block included 16 injection protocols, i.e., each block consisted of 16 different combinations of four ICs and four injection durations. Furthermore, using the maximum value of different error metrics, the error bars were created across all the organs and injection protocols studied.

3. Results

Applying both the analytical inverse and iterative stripping methods, the desired injection functions as well as the predicted and desired organ enhancement curves for the aorta, kidneys, liver, stomach, and small intestine were calculated based on the 32 original input injection functions. Figure 3 shows the enhancement curves calculated in the kidneys by applying the two methods on one selected uniphasic (injection of 125 mL of contrast medium of IC at ) as well as one selected biphasic (injection of 50 mL of the same contrast medium at followed by 75 mL at ) injection protocol.

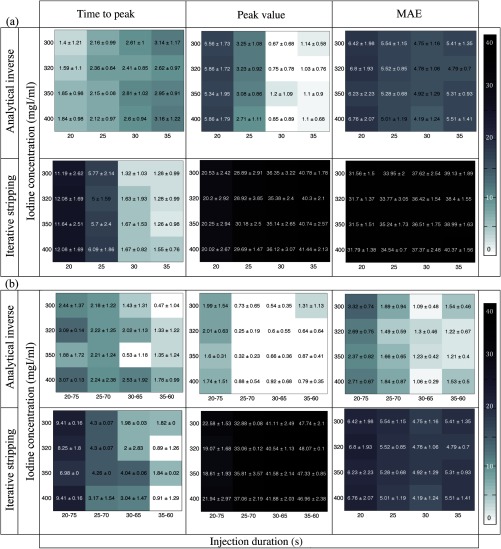

Figure 4 shows the error map generated using the time-to-peak, peak value, and MAEs calculated for the two methods across uniphasic [Fig. 4(a)] and biphasic [Fig. 4(b)] injections. Each concentration-duration combination cell in the error blocks reports the averaged error computed over 58 patient models, i.e., the number represents the across all the models.

Fig. 4.

Error map created for the kidneys. The time-to-peak, peak value, and MEAs in the prediction of the contrast enhancement in the kidney are based on the predicted injection functions applying the analytical inverse and iterative stripping methods across (a) uniphasic and (b) biphasic injection protocols. Each block includes 16 different combinations of four ICs ( axis) and four injection durations ( axis).

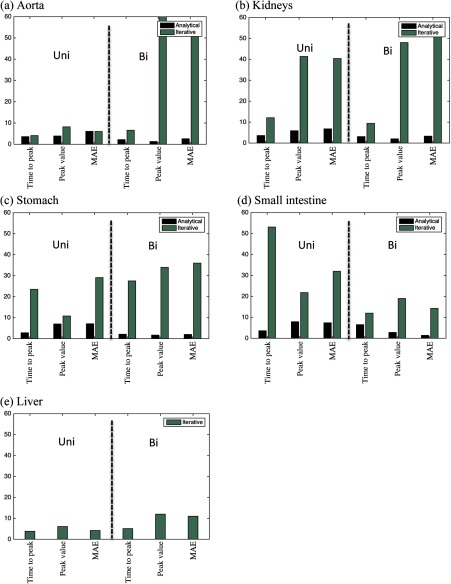

Figure 5 compares the maximum value of each error metric averaged over all the patients for all the organs studied. The maximum value of the time-to-peak, peak value, and MAE results from both methods across the uniphasic and biphasic protocols are summarized in Table 3. As described in Sec. 2, the analytical inverse method, per design, was incapable of predicting the injection function based on the liver enhancement.

Fig. 5.

Error bars created for different organs. The maximum value of errors in prediction of the contrast enhancement based on predicted injection functions applying both analytical inverse (dark) and iterative stripping (light) methods across uniphasic (left) and biphasic (right) injection protocols are shown for (a) aorta, (b) kidney, (c) stomach, (d) small intestine, and (e) liver.

Table 3.

Contrast material administration protocols. 32 different injection protocols composed of four different ICs, four different injection durations, and two injection bolus shapes (uniphasic and biphasic) were studied.

| Aorta | Kidneys | Stomach | S-intestine | Liver | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical inverse | Uniphasic | TP | |||||

| PV | |||||||

| MAE | |||||||

| Biphasic | TP | ||||||

| PV | |||||||

| MAE | |||||||

| Iterative stripping | Uniphasic | TP | |||||

| PV | |||||||

| MAE | |||||||

| Biphasic | TP | ||||||

| PV | |||||||

| MAE | |||||||

In general, the results from the iterative stripping method were not as accurate as those from the analytical inverse, hence the relatively darker error boxes in Fig. 4 and the larger error bars in Fig. 5.

4. Discussion

Many clinical practices utilize intravenous contrast medium enhancement techniques for body CT to improve image quality. To reach consistency in contrast enhanced image acquisition, the concordance of the organ enhancement time and the timing of the scan is extremely important. However, the current practice of contrast medium administration is not consistent across different clinics and often not reflective of the patient’s attributes, thus making quantitative analysis of contrast medium enhancement difficult. In this paper, applying knowledge of the mechanism of contrast enhancement, we introduced two techniques, analytical inverse and iterative stripping, to determine the required injection function to pave the way toward achieving targeted contrast enhancement in a specific organ. The two techniques introduced in this paper were designed based on our previously validated physiologically based compartmental model (forward model). The simulated contrast enhancement-time results from our compartmental model (forward model) demonstrated encouraging concordance to the clinical data from 55 patients (error for time-to-peak and peak value error metrics in aorta).

The predicted organ enhancement results from the analytical inverse technique showed an encouraging agreement with the desired organ enhancement results. The maximum value of the time-to-peak, peak value, and MAEs computed for the studied organs, averaged over 58 adult XCAT models, were for uniphasic injection protocols. In general, the results from the biphasic protocols were more accurate, which can be explained as the result of the longer injection duration of the biphasic protocols (95 s) in contrast to the uniphasic injection duration (25 to 35 s), hence more data points were present. Considering the accuracy level of the results across the different organs (i.e., ), the analytical inverse model can be considered a robust method to predict the right injection function to obtain a targeted contrast enhancement.

However, the analytical inverse method cannot be applied to determine the injection function based on contrast enhancement in the liver. This limitation can be explained by the fact that the liver, in contrast to other organs, is supplied by two sources, the hepatic artery and the portal vein.18 Our compartmental model has embodied this anatomical fact in its design. Consequently, the differential equations that provide the IC in the liver cannot be solved inversely from the liver back toward the injection vessel.

In general, the predicted injection function results from the iterative stripping model were not as accurate as those produced using the analytical inverse technique. However, the iterative stripping method was able to produce accurate results for the liver; the maximum error across the three used error metrics was . The maximum error was up to 68, 51, 36, and 14% for aorta, kidneys, stomach, and small intestine. Overall, the results indicate that combining the two methods, analytical inverse and iterative stripping, may be able to achieve better than 12% accuracy in delivering a desired organ enhancement based on a predicted injection function.

The error maps generated from the two methods also share one characteristic. Generally speaking, the variability in the injection time results in more discrepancies in the errors than the variability in the IC, i.e., more change in color along the individual rows of each error metric block for a specific organ in Figs. 3 and 4 than along the individual columns. This can be explained by the fact that, according to Eqs. (1)–(4), the change in concentration of the injected contrast material directly affects the calculated IC, while the relationship between the duration of injection and calculated IC is more complicated.

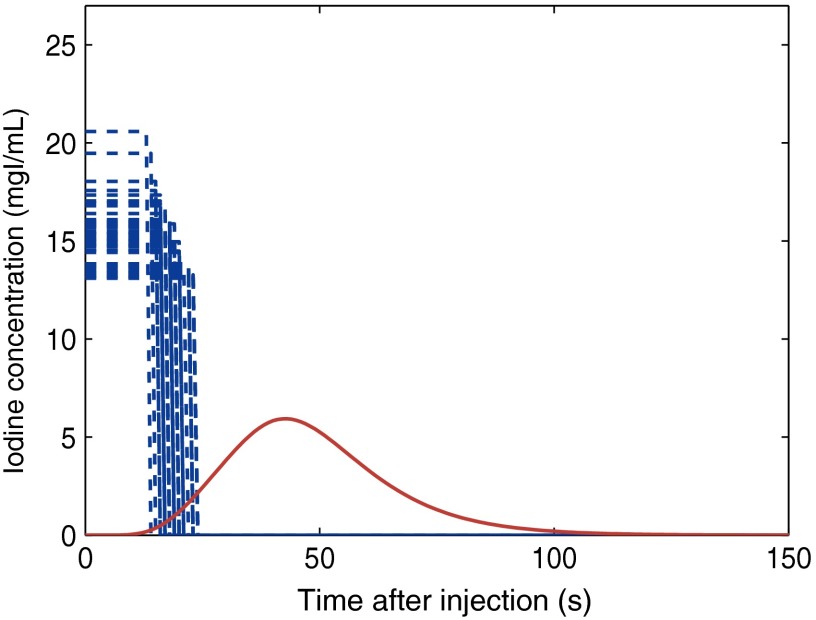

As described in Sec. 1, the lack of patient-specific (size, gender, anatomy, and physiology) contrast material administration techniques can result in enhancement inconsistency across different patients. Applying the method developed in this study, equipped with adjustable patient-specific parameters, enables us to design the required patient-specific injection function based on desired contrast enhancements to provide a more consistent method. As evidence to this claim, applying our method, we calculated the required injection function to achieve a given unique enhancement in the kidneys across our library of 58 XCAT models. Figure 6 demonstrates that the injection duration and IC level can vary up to 66% and 76% across the anatomically variable XCAT patients, respectively.

Fig. 6.

Required injection function to achieve a desired enhancement in the kidneys across our library of 58 XCAT models. Applying the analytical inverse method on a given contrast enhancement in the kidneys (solid line), different injection functions (dashed lines) were calculated for individual XCAT models.

In this paper, we could compare the enhancement results from predicted injection functions with the desired contrast enhancement curves, but due to the lack of explicit clinical enhancement data envisioned for this study, without presuming that our forward model is valid, we were not able to investigate the validity of our inverse methods against clinical data. Future work needs to include a systematic study to investigate the validity of the inverse techniques by comparison of simulated enhancement results with clinical enhancement data acquired from patients undergoing the predicted injection functions.

This study has other limitations. One limitation was that the compartmental model modeled only the distribution of the contrast material through the blood, and therefore, the methods developed here include only the intravenous injected contrast material and not orally taken contrast material. Second, the determination methods used in this study are single organ focused. There is a need for the holistic evaluation of contrast enhancement following an organ-directed protocol. Third, only a limited number of injection protocols were studied. However, the injection protocols studied were retrospectively selected from existing protocols in use at our institution such that they represent a wide range of injection durations and ICs. Fourth, since the physiologically based compartmental model was designed and validated with empirical data from adult patients, the results will also be applicable to adult patients only.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we developed two methods, analytical inverse and iterative stripping, to determine the required contrast medium injection function to achieve a desired contrast enhancement in specific organs by the incorporation of a physiologically based compartmental model of dynamics of contrast material distribution. By combining these two methods, we could achieve a better than 12% accuracy in delivering an organ enhancement based on a predicted injection function. Such an approach can be useful in optimizing contrast medium injection functions as well as the scan timing to provide more consistency in the way that contrast enhanced CT examinations are performed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. 2R01EB001838-09A1).

Biography

Biographies for the authors are not available.

References

- 1.Amato E., et al. , “A method to evaluate the dose increase in CT with iodinated contrast medium,” Med. Phys. 37(8), 4249–4256 (2010). 10.1118/1.3460797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sahbaee P., Samei E., Segars W., “SU-C-12A-03: the impact of contrast medium on radiation dose in CT: a systematic evaluation across 58 patient models,” Med. Phys. 41(6), 106–106 (2014). 10.1118/1.4887851 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heiken J., et al. , “Dynamic contrast-enhanced CT of the liver: comparison of contrast medium injection rates and uniphasic and biphasic injection protocols,” Radiology 187(2), 327–331 (1993). 10.1148/radiology.187.2.8475268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Small W., et al. , “Contrast-enhanced spiral CT of the liver: effect of different amounts and injection rates of contrast material on early contrast enhancement,” Am. J. Roentgenol. 163(1), 87–92 (1994). 10.2214/ajr.163.1.8010255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walkey M. M., “Dynamic hepatic CT: how many years will it take ’til we learn?,” Radiology 181(1), 17–18 (1991). 10.1148/radiology.181.1.1887029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bae K. T., “Intravenous contrast medium administration and scan timing at CT: considerations and approaches 1,” Radiology 256(1), 32–61 (2010). 10.1148/radiol.10090908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayes A. W., Principles and Methods of Toxicology, CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida: (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sahbaee P., Samei E., Segars W., “MO-E-17A-02: incorporation of contrast medium dynamics in anthropomorphic phantoms: the advent of 5D XCAT models,” Med. Phys. 41(6), 424–424 (2014). 10.1118/1.4889154 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith W., Hashemi J., Foundations of Materials Science and Engineering, McGraw-Hill, New York: (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Segars W., et al. , “Population of anatomically variable 4D XCAT adult phantoms for imaging research and optimization,” Med. Phys. 40(4), 043701 (2013). 10.1118/1.4794178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sahbaee P., et al. , “Determination of contrast media administration to achieve a targeted contrast enhancement in CT,” Proc. SPIE 9412, 941205 (2015). 10.1117/12.2082261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Segars W. P., et al. , “The development of a population of 4D pediatric XCAT phantoms for imaging research and optimization,” Med. Phys. 42(8), 4719–4726 (2015). 10.1118/1.4926847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Grieken R., Markowicz A., Handbook of X-ray Spectrometry, CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida: (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ligorría J. P., Ammon C. J., “Iterative deconvolution and receiver-function estimation,” Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 89(5), 1395–1400 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Statham P. J., “A comparative study of techniques for quantitative analysis of the x-ray spectra obtained with a Si (Li) detector,” X-Ray Spectrom. 5(1), 16–28 (1976). 10.1002/xrs.1300050106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Statham P. J., “Deconvolution and background subtraction by least-squares fitting with prefiltering of spectra,” Anal. Chem. 49(14), 2149–2154 (1977). 10.1021/ac50022a014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyndman R. J., Koehler A. B., “Another look at measures of forecast accuracy,” Int. J. Forecasting 22(4), 679–688 (2006). 10.1016/j.ijforecast.2006.03.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patton K. T., Thibodeau G. A., Mosby’s Handbook of Anatomy & Physiology, Elsevier Health Sciences, Philadelphia: (2014). [Google Scholar]