Abstract

Application of embryo related technology is dependent upon in vitro culture systems. Unfortunately most culture media are suboptimal and result in developmentally compromised embryos. Since embryo development is partially dependent upon Warburg Effect-like metabolism, it was our goal to treat embryos with compounds that are known to stimulate or enhance the Warburg Effect. One such compound is 5-(4-Chloro-phenyl)-3-phenyl-pent-2-enoic acid (PS48) which was found to improve both the percentage of embryos that reach the blastocyst stage and the number of nuclei in those blastocysts if it is added to the culture medium after fertilization. Treatment with PS48 resulted in more phosphorylated v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog (AKT) in the blastocyst stage embryos as compared to the controls. In contrast, PS48 addition during oocyte maturation compromised the quality of the subsequent embryo. Further, PS48 could replace bovine serum albumin in the embryo culture medium as demonstrated by high quality embryos that were developmentally competent. The action of PS48 appears to be via stimulation of phosphoinositide 3 kinase and phosphorylation of AKT. This action is consistent with stimulation of the Warburg Effect.

Keywords: Warburg Effect, metabolism, pig, blastocyst, bovine serum albumin

Introduction

Numerous embryo technological applications rely on the ability to create, culture and maintain early embryos in vitro. Thus a limiting factor in the application of these technologies is the environment in which these cells are cultured. One component consistently added to multiple culture media is bovine serum albumin (BSA). Unfortunately, different lots (or batches) of BSA result in different rates of oocyte maturation, or embryo development, and contaminants can confound embryo metabolism studies. Additionally, suboptimal in vitro conditions (Machaty et al. 1998) result in patterns of gene expression that are different from in vivo derived embryos (Bauer et al. 2010a; Redel et al. 2012; Whitworth et al. 2005; Whitworth et al. 2011). One of our goals has been to find physiologically relevant substitutes for BSA. Candidates to replace BSA should result in a pattern of gene expression that is more “in vivo-like”. Such candidates have been selected from transcriptional profiling data and have included low density lipoprotein (LDL) (Spate et al. 2010), and N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) and homocysteine (Spate et al. 2012).

We recently showed that metabolism in the early embryo has many similarities to the Warburg Effect (Redel et al. 2012): a shunting of glycolysis from the Krebs Cycle toward the Pentose Phosphate Pathway. Many highly proliferative cell types, such as cancer cells and stem cells, have a metabolism similar to the Warburg Effect (Vander Heiden et al. 2009). Cells exhibiting the Warburg Effect rely on aerobic glycolysis and they have spherical mitochondria containing few cristae, they produce nucleotides for DNA synthesis, secrete alanine and lactate, and consume glucose and glutamine. Stimulation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) induces many of the downstream effects, such as phosphorylation of v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog (AKT), that are consistent with the Warburg Effect. One growth factor known to induce phosphorylation of PI3K is colony stimulating factor 2 (CSF2). Addition of CSF2 to the culture system improves in vitro development of pig (Cui et al. 2004; Lee et al. 2013), human (Sjoblom et al. 2002), and cattle embryos (Loureiro et al. 2009). Another molecule that stimulates PI3K by activating phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 is 5-(4-Chloro-phenyl)-3-phenyl-pent-2-enoic acid (PS48) (Hindie et al. 2009; Zhu et al. 2010). Here we show that similar to CSF2, PS48 can enhance development of in vitro produced embryos, and that PS48 can replace BSA in the culture medium and produce developmentally competent embryos.

Results

The first experiment was designed to determine if PS48 would have any positive effects on oocyte maturation or development from the 1-cell to blastocyst stages. Addition of PS48 to the oocyte maturation conditions did not affect development to metaphase II, but compromised the quality of these oocytes by reducing the percent of oocytes that developed to the blastocyst stage after fertilization (Table 1). Oocytes exposed to PS48 that did develop to the blastocyst stage had fewer nuclei (Table 1). In contrast, when in vitro produced zygotes were cultured in PZM3 (Bauer et al. 2010b) in the presence of PS48 both the percent blastocyst and the total number of nuclei were enhanced as compared to the controls.

Table 1.

Development of pig embryos after exposure to 5 μM PS48 during oocyte maturation or culture from 1-cell to blastocyst.*

| Treatment Period | Replications | Percent Blastocyst (LS MEAN±SE) & | Total Nuclear Number (LS MEAN±SE) & |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oocyte Maturation + PS48 | 4 | 22.6±2.7 A | 25.9±1.3 C |

| Oocyte Maturation – PS48 | 4 | 30.2±2.6 B | 30.4±1.0 D |

| 1-cell to Blastocyst PZM3 + PS48 | 7 | 41.6±2.0 E | 30.5±0.5 G |

| 1-cell to Blastocyst PZM3 – PS48 | 7 | 35.2±2.0 F | 27.6±0.7 H |

For oocyte maturation N=598 for percent blastocyst and N=75 for total cell number. For embryo culture N=1,516 for percent blastocyst and N=297 for total cell number.

P=0.047,

P=0.008,

P=0.041,

P=0.0004.

Least Square Means ± Standard Error (LS MEAN±SE)

The second experiment was designed to determine if PS48 resulted in a similar improvement in the percent blastocyst when embryos were cultured in MU1 (PZM3 plus 1.69 mM arginine). The only endpoint measured here was the percent blastocyst and it was improved by the addition of PS48 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Development of in vitro produced embryos in MU1 with and without 5 μM PS48.*

12 replications,

P<0.05

Least Square Means ± Standard Error (LS MEAN±SE)

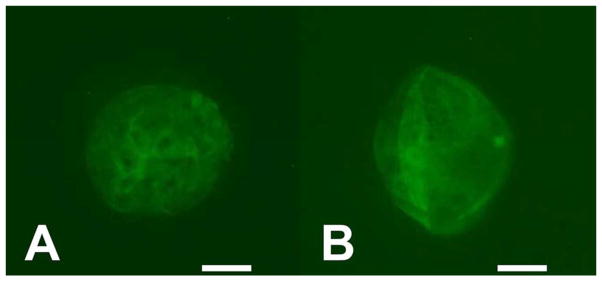

The third experiment was designed to determine a mechanism for the improvement of development in response to PS48. Here we used immunofluorescence to quantitate the amount of phosphorylated AKT in embryos cultured in MU1 or MU1 plus 5 μM PS48 (MU2). Sixty-five embryos were analyzed, 32 from MU1 cultured control embryos and 33 from MU2 cultured embryos. The mean intensity was higher for the PS48 treated embryos compared to the controls (P≤0.05: Table 3).

Table 3.

Immunofluorescence of phosphorylated AKT in in vitro produced pig embryos cultured in PS48.*

Four replications, N=65.

P=0.05

The fourth experiment was designed to determine if 5 μM PS48 could replace BSA in the culture medium. Similar to what was previously shown with PZM3 (Spate et al. 2012; Spate et al. 2010) removal of BSA from MU1 decreased the percentage of embryos that could develop to the blastocyst stage. PS48 in MU1 without BSA (now referred to as MU3) improved development above BSA- free medium and to a level not different from BSA containing-MU1 (Table 4). MU3 was compatible with term development as the transfer of 132 blastocyst stage embryos into three surrogates resulted in 2 pregnancies and 14 live born piglets (Table 5).

Table 4.

In vitro development of in vitro produced pig embryos in 5 μM PS48.*

| Treatment | n | Percent Blastocyst (LS MEAN±SE) & |

|---|---|---|

| MU1 | 405 | 34.6±6.4 A |

| MU1-BSA | 355 | 27.0±7.1 B |

| MU1-BSA + PS48 (MU3) | 561 | 36.2±5.4 A |

Eight replications,

P<0.05

Least Square Means ± Standard Error (LS MEAN±SE)

Table 5.

Results of three transfers of blastocyst stage embryos that had been cultured in MU3 from the 1-cell to blastocyst stage.

| Gilt | # Transferred | Day of Transfer | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| O521 | 42 | 5 | 5 piglets (4 live + 1 stillborn) |

| O571 | 50 | 5 | 10 piglets |

| O533 | 40 | 6 | Cycled day 51 |

Discussion

Previously the argument has been made that the early pig embryo shares a number of characteristics with stem cells and tumor cells. These characteristics are similar to what is described for the Warburg Effect (Redel et al. 2012). The Warburg Effect generally describes metabolism of glucose via lactic acid and the Pentose Phosphate Pathway, and not the Krebs Cycle. Early embryos share many of these characteristics; e.g. they have morphologically immature mitochondria, they use the Pentose Phosphate Pathway, and they express the fetal form of pyruvate kinase. The transcriptional profile of early embryos is also consistent with pushing metabolism away from the Krebs Cycle and towards the Pentose Phosphate Pathway (Krisher and Prather 2012).

The Warburg Effect can be induced by stimulating PI3K (Cordero-Espinoza and Hagen 2013). Interestingly, CSF2 binds to the CSF2RA and stimulates PI3K promoting the development of embryos. Similarly, PS48 is thought to function through the same signaling mechanism (Hindie et al. 2009) as both PS48 and CSF2 phosphorylate AKT. Message for both AKT1 and AKT2 is abundant in blastocyst stage embryos cultured in in vivo or in vitro (Bauer et al. 2010a). Phosphorylation of AKT stimulates Warburg Effect metabolism. A four week treatment with PS48 enhanced reprogramming of Oct4 transduced cells and activated Akt, increased lactate production and increased Warburg gene expression (Zhu et al. 2010). One action of PS48 is phosphorylation of AKT (Robey and Hay 2006). We found that treatment with PS48 increased the staining of blastocyst stage embryos with a phosphorylated AKT antibody. Phosphorylation of AKT (also known as protein kinase B) mediates both metabolism of the cell and its anti-apoptotic activity.

Here it was shown that PS48 treatment did not improve development if the treatment was only during oocyte maturation, but that treatment after fertilization improved both the percent of embryos that developed to the blastocyst stage, and increased the number of nuclei in those blastocysts.

Finally, one of the goals of our laboratory is to develop a system of embryo culture that does not require BSA. Since different batches of BSA have different abilities to promote embryo growth, we have an interest in developing a more defined set of culture conditions to both improve repeatability, and to better understand the metabolic regulation of early in vitro development. Our previous attempts at removing BSA have had varied effects (Spate et al. 2012; Spate et al. 2010). Here we showed that not only could PS48 replace BSA in the culture medium from fertilization to blastocyst and produce blastocysts at a rate not different from MU1 controls, but that these blastocysts were also developmentally competent as piglets were produced. The production of piglets is in contrast to one of our other attempts at developing a culture system that produced high quality blastocysts that appeared to not be developmentally competent (Spate et al. 2012). One action of BSA may be to stimulate surface receptors that then signal cellular proliferation via PI3K. We speculate this PI3K stimulation is mediated by a contaminant in BSA. Such a possibility would explain why some batches of BSA are effective at promoting in vitro development of oocytes or embryos, while other batches of BSA are less able to promote development. Describing such a defined system for embryo culture will not only make embryo production more reliable, but also helps to better define metabolism of early embryos that is consistent with viability.

In conclusion, PS48 can replace BSA in the medium for culturing pig embryos from the 1-cell stage to the blastocyst stage and PS48 appears to be acting via phosphorylation of AKT and stimulation of a pathway(s) consistent with the Warburg Effect.

Materials and methods

Embryo Production

Cumulus enclosed germinal vesicle stage oocytes (COCs) were obtained from the ovaries of prepubertal gilts recovered from a local slaughterhouse. The COCs were matured as previously described (Zhang et al. 2010). After maturation, metaphase-II oocytes were selected and fertilized in a modified Tris-buffered medium containing 2 mg/mL bovine serum albumin and 2 mM caffeine and fertilized as previously described (Redel et al. 2012)Except as noted below, after 5 hours the embryos were transferred to MU1 (porcine zygote medium 3 plus 3 mg/mL BSA (Yoshioka et al. 2002) and 1.69 mM arginine (Bauer et al. 2010b)) at 5% O2, 5% CO2 and 90% N2 in a humidified atmosphere at 38.5°C.

Phosphorylated AKT Abundance in Blastocyst Stage Embryos

Zona pellucida were removed from day 6 blastocysts by using acidified saline (pH = 1.7). The embryos were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in TL- Hepes for 20–25 minutes and then stored in TL-Hepes at 4°C until processing. Blastocysts were permeabilized with 0.1%Triton X100 in TL-Hepes for 15 minutes. Then they are moved to blocking solution (2% goat serum in TL-Hepes) for 1 hour at room temperature. Blastocysts were placed into a 1:50 dilution of primary antibody anti-phospho-Akt (pThr308 SAB4504332 Sigma-Aldrich) with TL-Hepes and 0.1% Triton X100 overnight at 4 °C and washed 3 times for 5 minutes each in TL-Hepes with 0.1% Triton X100. After washing, blastocysts were transferred to 1:500 dilution of secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotech sc-2359 FITC conjugated) in TL-Hepes with 0.1% Triton X100 at room temperature for 1 hour. Embryos were washed for 10 minutes in TL-Hepes with Hoechst to stain the nuclei and washed again in TL-Hepes with Triton X100. Finally, they were mounted by placing the embryos on a slide in a small drop of Vectashield mounting media (H-1000 Vector lab inc.) and treated as light sensitive until imaged. There were 2 negative control embryos for each replicate. Negative controls were processed the same as the 2 treatments with the omission of primary antibody to control for any background staining from the secondary antibody. The intensities from the negative control embryos were averaged together for each replicate had its own negative control. Embryos were imaged with a Nikon DS Fi1 or Nikon digital sight cameras and the florescence was measured using Nis Elements software BR3.22. Arbitrary units were calculated and differences in intensity were analyzed by using Proc GLM in SAS 9.4.

Embryo Transfers

Blastocysts were selected 6 days post fertilization and placed into 5 mL polystyrene tubes (BD Falcon 352054) containing 3 mL of manipulation media (Lee et al. 2013) + 5 μM PS48. The blastocysts were then transported to the to the University of Missouri Swine Research Complex where they were loaded into a tomcat catheter with minimal volume of media and surgically transferred to the oviduct of a cycling gilt on day 5 or 6 of her estrous cycle. Gilts were monitored visually for estrus and pregnancy was determined via ultrasound after day 25 and subsequently checked weekly until they returned to estrus or farrowed.

Experimental Design

PS48 during oocyte maturation: After aspiration selected COCs were either placed in 500 μL of maturation medium or maturation medium containing 5 μM PS48 (Stemgent, Inc, Cambridge, MA). They were cultured in 5% CO2 in air at 38.5°C for 42 hours then fertilized and moved to PZM3 and cultured for 6 days. The percentage of COCs that formed blastocysts was measured and the total cell number was determined after staining the embryos with Hoechst 33342. The concentration of PS48 was fixed at 5 μM throughout the study as this is the same concentration that is required for stem cells to retain their pluripotency (Liao et al. 2013; Zhu et al. 2010).

PS48 during embryo culture: After in vitro fertilization (4–5 hours of co-incubation with sperm) presumptive zygotes were washed in PZM3 or MU1 and cultured for another 20 hours. At 24 hours after insemination, embryos were collected and divided between culture in MU1 versus MU1 plus 5 μM PS48 (designated MU2) and cultured to day 6. On day 6, the percentage of embryos that developed to the blastocyst stage was noted and in some cases the number of nuclei was determined after staining with Hoescht 33342.

In another set of experiments BSA was removed from MU1, and 5 μM PS48 and 0.1% polyvinyl alcohol was added (designated MU3).

Compliance

Ovaries were collected at a USDA approved slaughterhouse, and animal procedures (semen collection and embryo transfer) were conducted under an approved institutional animal care and use committee protocol.

Figure 1.

Immunofluorescence images showing phosphorylated AKT in blastocyst stage pig embryos that had been cultured in the absence (A) or presence (B) of PS48. Note that the staining is predominately cytoplasmic and not nuclear.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Clifton N. Murphy for his advice and encouragement, and Bhanu Telugu for his thoughts about PS48.

Funding: Financial support was from Food for the 21st Century at the University of Missouri, and from the National Institutes of Health to R.S.P. (R01 HD080636) and the National Swine Resource and Research Center at the University of Missouri (U42 OD011140).

Abbreviations

- AKT

v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog

- AKT1

v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 1

- AKT2

v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 2

- BSA

Bovine serum albumin

- COCs

Cumulus enclosed germinal vesicle stage oocytes

- CSF2

Colony stimulating factor 2

- CSF2RA

Colony stimulating factor receptor 2A

- LDL

Low density lipoprotein

- MU1

Missouri University 1 medium

- MU2

MU1+5 μM PS48

- MU3

MU1-BSA+5 μM PS48

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartic acid

- Oct4

POU class 5 homeobox 1

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase, catalytic subunit alpha

- PS48

5-(4-Chloro-phenyl)-3-phenyl-pent-2-enoic acid

- PZM3

Porcine zygote medium 3

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Bauer BK, Isom SC, Spate LD, Whitworth KM, Spollen WG, Blake SM, Springer GK, Murphy CN, Prather RS. Transcriptional profiling by deep sequencing identifies differences in mRNA transcript abundance in in vivo-derived versus in vitro-cultured porcine blastocyst stage embryos. Biology of reproduction. 2010a;83(5):791–798. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.085936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer BK, Spate LD, Murphy CN, Prather RS. Arginine supplementation in vitro increases porcine embryo development and affects mRNA transcript expression. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2010b;23:107. [Google Scholar]

- Cordero-Espinoza L, Hagen T. Increased concentrations of Fructose-2,6-bisphosphate contribute to the Warburg effect in PTEN-deficient cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.510289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui XS, Lee JY, Choi SH, Kwon MS, Kim T, Kim NH. Mouse granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor enhances viability of porcine embryos in defined culture conditions. Animal reproduction science. 2004;84(1–2):169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindie V, Stroba A, Zhang H, Lopez-Garcia LA, Idrissova L, Zeuzem S, Hirschberg D, Schaeffer F, Jorgensen TJ, Engel M, Alzari PM, Biondi RM. Structure and allosteric effects of low-molecular-weight activators on the protein kinase PDK1. Nature chemical biology. 2009;5(10):758–764. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krisher RL, Prather RS. A role for the Warburg effect in preimplantation embryo development: metabolic modification to support rapid cell proliferation. Mol Reprod Dev. 2012;79(5):311–320. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Redel BK, Spate L, Teson J, Brown AN, Park KW, Walters E, Samuel M, Murphy CN, Prather RS. Piglets produced from cloned blastocysts cultured in vitro with GM-CSF. Mol Reprod Dev. 2013;80(2):145–154. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao J, Marumoto T, Yamaguchi S, Okano S, Takeda N, Sakamoto C, Kawano H, Nii T, Miyamato S, Nagai Y, Okada M, Inoue H, Kawahara K, Suzuki A, Miura Y, Tani K. Inhibition of PTEN tumor suppressor promotes the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2013;21(6):1242–1250. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loureiro B, Bonilla L, Block J, Fear JM, Bonilla AQ, Hansen PJ. Colony-stimulating factor 2 (CSF-2) improves development and posttransfer survival of bovine embryos produced in vitro. Endocrinology. 2009;150(11):5046–5054. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machaty Z, Day BN, Prather RS. Development of early porcine embryos in vitro and in vivo. Biology of reproduction. 1998;59(2):451–455. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod59.2.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redel BK, Brown AN, Spate LD, Whitworth KM, Green JA, Prather RS. Glycolysis in preimplantation development is partially controlled by the Warburg Effect. Molecular reproduction and development. 2012;79(4):262–271. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robey RB, Hay N. Mitochondrial hexokinases, novel mediators of the antiapoptotic effects of growth factors and Akt. Oncogene. 2006;25(34):4683–4696. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjoblom C, Wikland M, Robertson SA. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) acts independently of the beta common subunit of the GM-CSF receptor to prevent inner cell mass apoptosis in human embryos. Biology of reproduction. 2002;67(6):1817–1823. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.101.001503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spate LD, Redel BK, Brown AN, Murphy CN, Prather RS. Replacement of bovine serum albumin with N-methyl-D-aspartic acid and homocysteine improves development, but not live birth. Mol Reprod Dev. 2012;79(5):310. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spate LD, Whitworth KM, Walker KA, Bauer BK, Murphy CN, Prather RS. Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor mRNA and protein may enable LDL to replace bovine serum albumin during the in vitro swine embryo development. Mol Reprod Dev. 2010;77(4):298. doi: 10.1002/mrd.21141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324(5930):1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitworth KM, Agca C, Kim JG, Patel RV, Springer GK, Bivens NJ, Forrester LJ, Mathialagan N, Green JA, Prather RS. Transcriptional profiling of pig embryogenesis by using a 15-K member unigene set specific for pig reproductive tissues and embryos. Biology of reproduction. 2005;72(6):1437–1451. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.037952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitworth KM, Zhao J, Spate LD, Li R, Prather RS. Scriptaid corrects gene expression of a few aberrantly reprogrammed transcripts in nuclear transfer pig blastocyst stage embryos. Cellular reprogramming. 2011;13(3):191–204. doi: 10.1089/cell.2010.0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka K, Suzuki C, Tanaka A, Anas IM, Iwamura S. Birth of piglets derived from porcine zygotes cultured in a chemically defined medium. Biology of reproduction. 2002;66(1):112–119. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod66.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Miao Y, Zhao JG, Spate L, Bennett MW, Murphy CN, Schatten H, Prather RS. Porcine oocytes denuded before maturation can develop to the blastocyst stage if provided a cumulous cell-derived coculture system. Journal of animal science. 2010;88(8):2604–2610. doi: 10.2527/jas.2009-2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S, Li W, Zhou H, Wei W, Ambasudhan R, Lin T, Kim J, Zhang K, Ding S. Reprogramming of human primary somatic cells by OCT4 and chemical compounds. Cell stem cell. 2010;7(6):651–655. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]