Abstract

The ectotympanic, malleus and incus of the developing mammalian middle ear (ME) are initially attached to the dentary via Meckel's cartilage, betraying their origins from the primary jaw joint of land vertebrates. This recapitulation has prompted mostly unquantified suggestions that several suspected—but similarly unquantified—key evolutionary transformations leading to the mammalian ME are recapitulated in development, through negative allometry and posterior/medial displacement of ME bones relative to the jaw joint. Here we show, using µCT reconstructions, that neither allometric nor topological change is quantifiable in the pre-detachment ME development of six marsupials and two monotremes. Also, differential ME positioning in the two monotreme species is not recapitulated. This challenges the developmental prerequisites of widely cited evolutionary scenarios of definitive mammalian middle ear (DMME) evolution, highlighting the requirement for further fossil evidence to test these hypotheses. Possible association between rear molar eruption, full ME ossification and ME detachment in marsupials suggests functional divergence between dentary and ME as a trigger for developmental, and possibly also evolutionary, ME detachment. The stable positioning of the dentary and ME supports suggestions that a ‘partial mammalian middle ear’ as found in many mammaliaforms—probably with a cartilaginous Meckel's cartilage—represents the only developmentally plausible evolutionary DMME precursor.

Keywords: allometry, detachment, middle ear bones, Synapsida

1. Introduction

The transformation of the mammalian middle ear (ME) from load-bearing jaw joint elements (angular, articular/prearticular and quadrate) to delicate auditory ossicles (ectotympanic, malleus/gonial and incus) separate from the mandible is one of the oldest subjects of developmentally informed inference of evolutionary patterns [1,2]. The homology between parts of the primary jaw joint with the modern definitive mammalian middle ear (DMME) [3,4] was famously formulated by nineteenth-century German anatomist Carl Bogislavs Reichert [5], based on embryological finds [6] that the anterior leg of the developing mammalian Meckel's cartilage—the cartilaginous precursor of the articular (or body of the malleus [4])—resides in Meckel's groove [4], a furrow on the medial side of the dentary (figures 1 and 2). The developing ME detaches from the lower jaw when the anterior leg of Meckel's cartilage is absorbed [7–9], a process coinciding with a disappearance of Meckel's groove in the development of extant mammals [7,8].

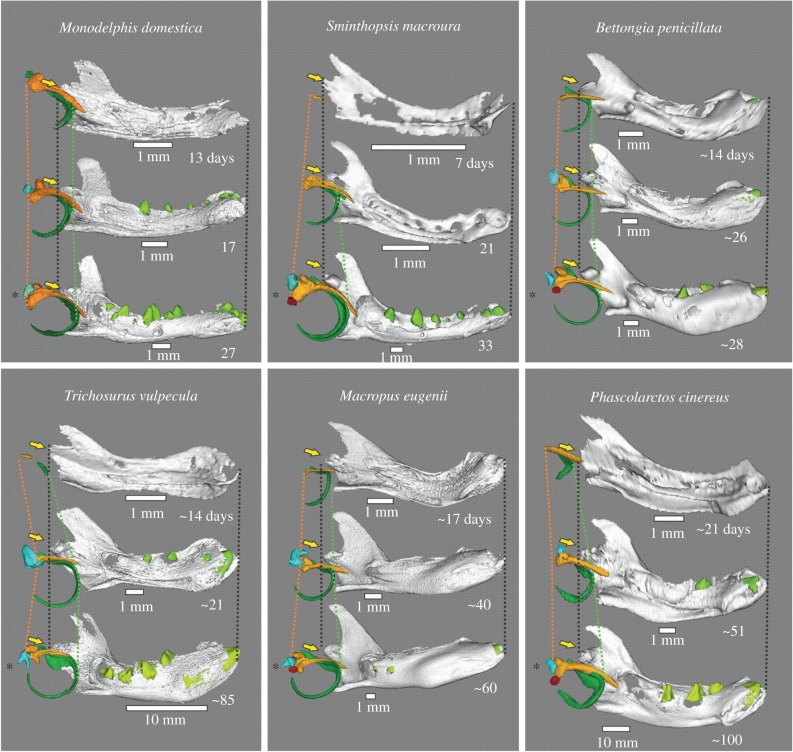

Figure 1.

Medial view of ME and dentary of selected specimens, each with a young specimen with well-developed Meckel's groove (top), incipient dental eruption stage (middle) and detached ME (bottom; with asterisk). Orange, malleus; green, ectotympanic; blue, incus; red, stapes; light green, teeth. Lines indicate posterior-most extent of malleus head (orange) and anterior-most rim of the ectotympanic ring (green). Yellow arrows indicate the position of the dentary condyle.

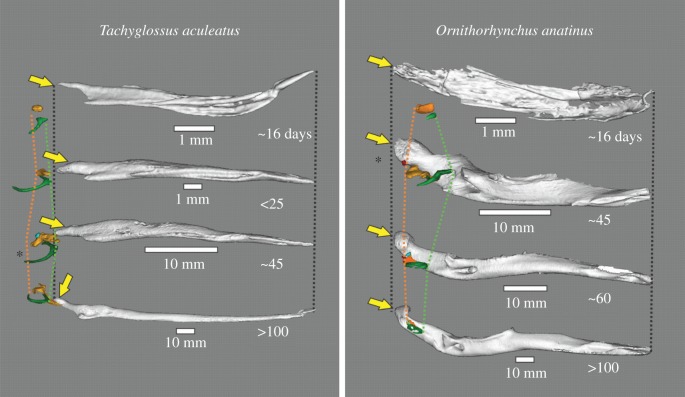

Figure 2.

ME and dentary of selected monotreme specimens, from medial view. Orange, malleus; green, ectotympanic; blue, incus; red, stapes; light green, teeth. Lines indicate posterior-most extent of malleus head (orange) and anterior-most rim of ectotympanic ring (green). Asterisk identifies specimens with a detached ME and no Meckel's groove. Note the swing of the Tachyglossus dentary from a vertical to a horizontal position. Yellow arrows indicate the position of the dentary condyle.

The DMME is known from multituberculates, cladotherians (including dryolestids, extant marsupials and placentals [10]) and extant monotremes; the number of times it evolved remains controversial [11,12]. It was initially thought to have arisen from the mandibular middle ear of non-mammalian cynodonts (MMEC) and early mammaliaforms, whose post-dentary bones are housed in a mandibular trough on the medial surface of the dentary. However, more recently a ‘partial’ [4] or ‘transitional’ [13] mandibular middle ear (PMME) was identified from several symmetrodont and eutriconodont mammaliaforms whose ossified Meckel's cartilage remained in Meckel's groove during adulthood. Two eutriconodonts were found with the ossicular chain attached to this ossified Meckel's cartilage [9,13,14], leading to suggestions that all species with a PMME also have this condition [9,13,14]. The retention of a Meckel's groove is widespread in mammaliaforms, prompting suggestions that retention of a PMME [4,8,14] may have been an important character transformation and transitional ‘phylogenetic stage’, possibly required to stabilize the ossicular complex [13,15]. This is congruent with the resemblance between the developing DMME of extant mammals and the PMME, supporting suggestions that DMME development of extant mammals recapitulates a final evolutionary detachment of the DMME through disappearance of Meckel's cartilage [4,9,16].

The partial developmental recapitulation of DMME evolution in extant mammals has prompted decades of embryological research for a finer-grained impression of the processes involved in DMME detachment. This embryological inference suggested a pattern of negative allometry and medial/posterior displacement of ME bones relative to the jaw and skull [4,17–20]. These inferences fit the traditional notion that a conflict between the load-bearing function of the jaw joint and increasing specialization of the post-dentary bones for sound conduction lead to small and gracile bones positioned away from the jaw joint [19,21], possibly in relation to selection for high-frequency hearing [22,23]. In addition, the popular ‘brain expansion hypothesis’ (BEH, [18]) suggested that extant mammalian development recapitulates a complicated evolutionary process, wherein the expanding brain triggered the relative miniaturization and displacement of ME bones. The BEH remains widely cited, despite criticisms that its developmental database was unreliable [24], that two eutriconodonts with a PMME are in fact smaller brained than cynodonts and early mammaliaforms with an MMEC [15], and emerging evidence that initial descriptions of Hadrocodium wui as the first mammaliaform with both a large brain and a detached ME were inaccurate due to the juvenile state of the fossil [25,26].

Most current scenarios on the evolution of the DMME assume that negative allometry and displacement of the ME from the jaw joint are real evolutionary processes observable in mammalian development [4,16–18]. However, none of these developmental processes has been quantitatively demonstrated. This is problematic because two proposed transformations—negative allometry and posterior movement of ME bones relative to the jaw joint—have also never been quantified in fossil taxa. Evidence for negative allometry is limited to comments that the post-dentary bones decrease in relative size between cynodonts and mammaliaforms [4,27], and PMMEs compared with DMMEs [13,27]. Evolutionary posterior movement is only inferred through a scenario where evolutionary brain expansion forced a posterior ME displacement because its connection to the inner ear—the fenestra vestibuli—was pushed back [18]. Lastly, while a medially positioned ossicular chain is seen in complete fossil PMMEs [4,9], developmental recapitulation of a medial movement is only inferred from historical histological studies [4], particularly of monotremes [28–30].

Here, we present the first quantitative developmental study to test the notion that specific processes of ME development of extant mammals can provide support for hypothesized transformations in the evolution of the DMME. This is done through large-scale, cross-species investigation of ME development in six marsupial and two monotreme species. Marsupials are the organism of choice for studies of therian ME development because of the easy accessibility of young, plesiomorphic arrangement of ME bones and clear ossicular development [8,16,19]; monotremes are crucial because their lineage possibly evolved a DMME independently [31,32], and because they may provide evidence for developmental recapitulation of medial ME movement [4]. Using the developmental disappearance of Meckel's groove as a proxy for ME detachment, we test claims that ME development recapitulates a pattern of negative allometry and displacement that could be extrapolated to the evolution of the mammaliaform DMME.

2. Material and methods

(a). Data collection

Developmental series were collected from two monotremes (platypus and short-beaked echidna) and six marsupials, the latter comprising a didelphimorphian opossum, a dasyuromorphian dunnart and four diprotodontians (a woylie or ‘rat kangaroo’, tammar wallaby, koala and brush-tailed possum). For accession details, preservation and age estimates, see the electronic supplementary material, table S3 and materials and methods.

(b). Middle ear detachment time

The time of detachment of the ME bones from the dentary was documented through determining the presence or the absence of Meckel's groove, which is the last point of contact between the dentary and the ME in extant and probably also extinct mammals (see Introduction). While the absence of a groove may not reflect complete resorption of the cartilage, lack of a substantial connection between dentary and ME can be assumed (see Introduction). Ossification of the auditory chain and eruption of molariforms was also documented to provide a time-frame reference for ME detachment relative to other developmental events.

(c). Allometry analyses

We measured proxies of cranial size (condylobasal length, dentary length) and proxies of ME size, including the diameter of the ectotympanic ring and its bullar part (the latter being only available in marsupials) and the anteroposterior length of the gonioarticular portion of the malleus (electronic supplementary material, figure S1, and tables S1 and S4). Allometric coefficients between ectotympanic and malleus lengths against condylobasal and dentary length were determined using standardized major axis (SMA) regression executed in R software [33] using the package ‘smatr’ [34]. Negative or positive allometry was identified when the coefficients significantly deviated from unity, with α = 0.01 [35]. Owing to sample size limitations, pre-detachment analyses were not performed for Ornithorhynchus anatinus and Bettongia penicillata. Post-detachment analyses were only performed in B. penicillata and Tachyglossus aculeatus by. For other species with smaller sample sizes, we only evaluated the position of data points relative to the pre-detachment slope by estimating the slope of post-detachment data regressions that were forced through the oldest pre-detachment specimen. We also included assessments of allometry in the external auditory meatus of marsupials (electronic supplementary material, table S1), although specimen numbers limit the reliability of this regression as it is formed well after detachment of ME bones in most of the species evaluated.

(d). Tests for middle ear displacement from the dentary

Anteroposterior separation of the ME from the dentary-squamosal jaw joint was assessed by measuring the distance from the anterior-most tip of the dentary to the anterior-most tip of the ectotympanic ring, the distance between the anterior-most part of the dentary and the posterior part of the malleus, and the distance of the anteroposterior length of the dentary at the level of the condyloid process (‘dentary length’; electronic supplementary material, figure S1). We assigned a value of one to the dentary length, with the other two distances calculated as a proportion of this value. Values greater and smaller than one indicate movements to a more anterior and posterior positions, respectively, relative to the dentary condyle (electronic supplementary material, table S2).

Developmental mediolateral displacement of ME bones from the dentary was tested by regressing the distances between the heads of the two mallei against the distance between the condyloid processes of each dentary (measured as in the electronic supplementary material, figure S1). For each species, these measurements were compared using Spearman's rank correlations (electronic supplementary material, table S2). We expected a negative correlation in case of medially directed movement of the malleus relative to the dentary.

3. Results

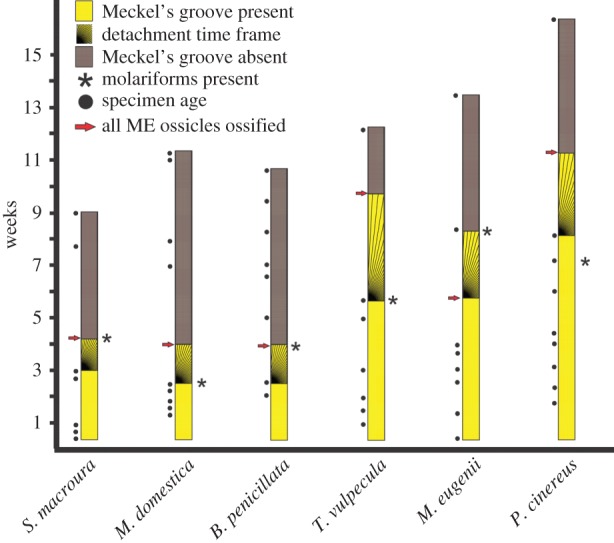

Detachment tends to occur earlier in smaller marsupials (figure 3). It also tends to occur close to the eruption of molariform teeth (premolars/molars; figures 1 and 3) in marsupials. Full ossification of the ossicular chain (including the stapes) is also complete close to the detachment time; the bullar portion of the ectotympanic formed much later. Meckel's groove of T. aculeatus disappears around the seventh week post-hatching; our oldest O. anatinus specimen with a Meckel's groove was aged around 35 days.

Figure 3.

Summary graph of ME detachment timing, as inferred by disappearance of Meckel's cartilage, in relation to specimen age, dental eruption and ossicle ossification. Species are ordered from smallest to largest skull length (left to right). ‘Molariforms’ includes premolars and molars. Hatched areas represent gaps between the last specimen with Meckel's groove and the first specimen without Meckel's groove, representing the window of time during which ME detachment happens. (Online version in colour.)

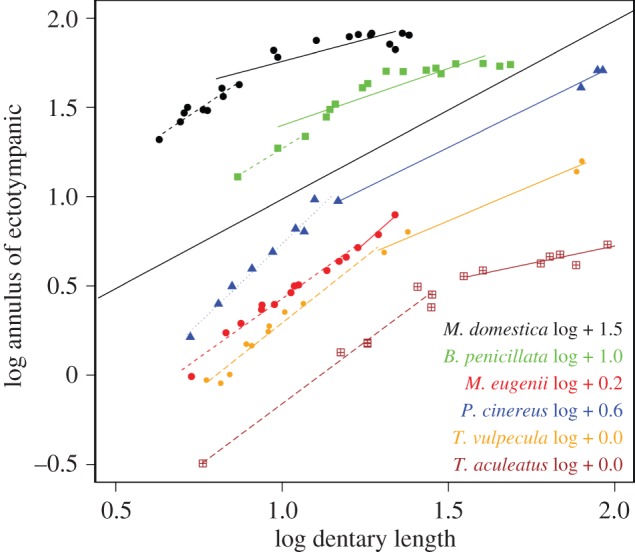

Before ME detachment, the ectotympanic and malleus of marsupials and monotremes grow with positive allometry relative to both cranium and dentary (figure 4; electronic supplementary material, table S1). A switch to patterns of negative allometry (quantified or inferred as noted above) occurs after detachment (figure 4; electronic supplementary material, table S1). However, the ectotympanic and malleus continue growth until well after ME detachment in all species (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Regressions of ectotympanic annulus dimensions against dentary length in all species sampled, before (dashed lines) and after (solid lines) Meckel's cartilage detachment. The lines have artificial intercepts added to avoid superimposition (black line is line of isometry). Post-detachment lines with fewer than five specimens are estimates with the origin of the line forced through the oldest pre-detachment specimens to ensure a conservative estimate of slope.

The positions of the ectotympanic or malleus relative to the dentary condyles show little displacement across ME detachment. Possibly due to expansion of ossification, slight anterior movements are more common than slight posterior ones (figure 1; electronic supplementary material, table S2). Medial displacement was also not apparent in either monotremes or marsupials, as inter-malleus distances and inter-condylar distances (figure 1) increase by identical magnitudes (electronic supplementary material, table S2) in all species. Notably, the dentary, ectotympanic and malleus of the echidna all perform a ‘flipping’ movement away from their original vertical position to the adult horizontal orientation (figure 2). Monotremes are also unusual in that they display divergent positioning of the fenestra vestibuli (FV) relative to the jaw joint: in the platypus, the FV and ME ossicles are situated just anterior to the craniomandibular joint, unlike the situation in the echidna (figure 5; electronic supplementary material, table S2).

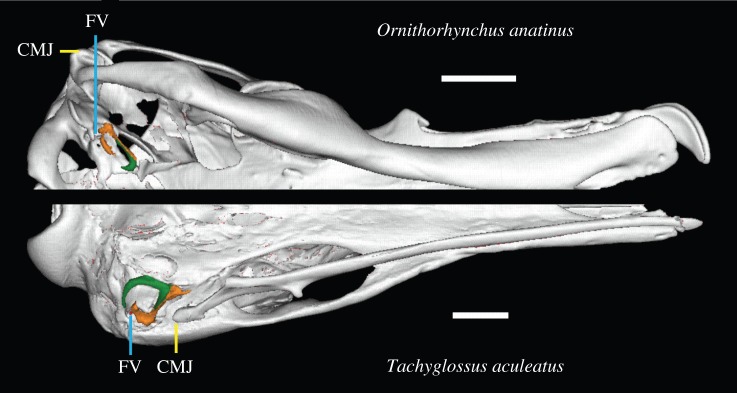

Figure 5.

Virtual reconstruction of ME region of a platypus (top) and an echidna (bottom) in ventral view. Note divergent positioning of the fenestra vestibule (FV) and craniomandibular joint (CMJ). Scale bars, 10 mm. (Online version in colour.)

4. Discussion

Our results provide several lines of evidence against the proposition that developmental data from extant marsupials and monotremes support hypothesized processes of DMME evolution. In particular, we found no evidence for the hypotheses that either negative allometry or displacement of the ME bones relative to the skull or jaw joint are associated with the detachment of the ME during mammalian development. Also, contrary to previous suggestions [4], ME development of monotremes and marsupials was similar overall, except for the unusual horizontal rearrangement of the echidna dentary and ME (see below). Therefore, if ME detachment occurred independently in the prototherian and therian lineages [4,31], this is not obvious through developmental differences. The only between-species variation within our sample reflects allometry of detachment timing (later in larger species). This contradicts suggestions of a uniform three-week detachment time in marsupials [8,18,36], but is consistent with allometric developmental schedules elsewhere in the mammalian body [24].

Negative allometry is the most widely accepted hypothesized trigger of evolutionary and developmental ME detachment in mammals and their ancestors [4,8,20]. This follows the reasoning that the ME bones should have been selected for small sizes that would have improved their ability to conduct sound [3,18,37]. However, negative allometry must precede ME detachment to qualify as a trigger of the detachment process, in both evolution and development. By contrast, patterns of negative allometry only occur after ME detachment in all species investigated in this study. Our finding of continued post-detachment growth of the ectotympanic and malleus also contradicts the hypothesis [8] that developmental negative allometry is caused by a stalling of ossicle growth after ossification. These results remove the developmental support for the otherwise unquantified hypothesis that negative allometry was a trigger of ME detachment in Mesozoic mammals [17,18].

Our results also contradict the assumption [4,18,27] that evolutionary topological changes of the ME relative to the jaw joint are recapitulated in marsupial or monotreme development. In particular, lack of posterior movement during ME development contradicts the tenet of the BEH [18] that the developing brain pushes the fenestra vestibuli (FV)—and associated ME bones—into a more posterior position relative to the jaw joint, recapitulating similar evolutionary process [18]. Moreover, mammals with a DMME vary in their FV positioning; it is at the same level as, or slightly anterior to, the jaw joint in the platypus and multituberculates, but it is posterior to the jaw joint in the echidna and therians [38]. Together with our developmental evidence, this suggests that changes in FV position and brain size expansion represent unrelated evolutionary events.

The divergent FV positioning within monotremes also has implications for the degree to which developmental data can be used to infer evolutionary transformations both in the ME and other skeletal traits. The position of the FV in relation to the craniomandibular joint must have repositioned relatively recently, after the divergence between echidnas and platypus, roughly in the Mid-Miocene [39]. The anterior position of the FV is probably a trait unique to the modern platypus, since the FV of the Miocene platypus Obdurodon dicksoni shares a posterior FV position with the echidna [40]. Despite this recent transformation, neither monotreme recapitulates a developmental position change of the FV (figure 2; see also histological evidence in early stages [30,41]). This casts doubt on the assumption that developmental observations in extant mammals contain reliable information on topological changes during the evolution of ME detachment as well as possibly other parts of the skeleton.

Our results highlight the lack of developmental support for suspected triggers of evolutionary mammalian ME detachment, contradicting the proposal that brain expansion is related to this process [36,42]. At least for developing marsupials, a connection of detachment to dentary function seems more likely, given the consistent timing of ME detachment with molariform tooth eruption and full ME ossification in our sample. This coincidence of timing might relate to the functional transformation where the ME assumes its sound-conducting role and the dentary takes over biomechanical loading related to mastication [3,37] or sucking [20]. Such an explanation provides some tentative support for more traditional functional explanations of ME evolution, which also focus on the dichotomy of adaptation in the dentary (for mastication) and ME (for improved hearing, particularly at high frequencies) as triggers of ME detachment [20,37,43]. Further fossil evidence, as well as more detailed work on the biomechanics of the developing and evolving jaw joint, is needed to resolve these issues.

The ectotympanic and malleus of developing echidnas participate in a reorientation of the dentary from a vertical to a horizontal position. Together with the lack of topological change relative to the jaw joint in our sample, this suggests that the ME and lower jaw represent a developmental unit. This matches observations in rodents, where ME and dentary remain connected through sphenomandibular ligaments derived from the remnants of Meckel's cartilage [8,13,44]. The sphenomandibular ligament and the existence of a PMME in the fossil record have been used to argue that the DMME evolved from a ‘phylogenetic stage’ [13,14] of a PMME several times through a simple transformation of Meckel's cartilage into a sphenomandibular ligament (summarized in [14]). The existence of a PMME in some symmetrodonts and eutriconodonts supports this scenario [4,13,14], but their ossified Meckel's cartilage is a unique departure from the plesiomorphic cartilaginous condition in vertebrates and in mammalian development [4]. An ossified Meckel's cartilage is often considered as resulting from a paedomorphic retention of Meckel's cartilage, arising from an ancestral condition where a DMME was present [4,9,13,14]. However, given the widespread presence of Meckel's groove in Mesozoic mammaliaforms, it seems at least equally likely that a PMME with a cartilaginous Meckel's cartilage was widespread [14]. If so, an ossified Meckel's cartilage may represent a peramorphic ‘over-development’ of an ancestral condition with a cartilaginous Meckel's cartilage. This scenario is contingent on Meckel's groove of Mesozoic mammaliaforms holding a cartilaginous Meckel's cartilage attached to the ME bones. This seems probable because the alternatives are that these Meckel's grooves did not contain a Meckel's cartilage, or that a Meckel's cartilage was retained but separated from the ME bones. Neither of these are observed in mammalian development, while a PMME-like arrangement is. We therefore agree with the proposal [13] that a PMME is a developmentally plausible precursor to ME detachment in mammaliaforms, adding that an ossified Meckel's cartilage in some form was possibly a peramorphic exception.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank C. Kemper and D. Stemmer (Mammal Collection of the South Australian Museum) for access to Bettongia and monotreme specimens, and H. Janetzki (Queensland Museum), D. Pickering (Museum Victoria) and S. Ingleby (Australian Museum) for access to monotreme specimens. We thank K. Mardon (Centre for Advanced Imaging, University of Queensland) for help with µCT scanning. Many thanks to T. Rowe and T. Macrini for providing post-detachment Monodelphis specimens (acquired under National Science Foundation grants IIS 0208675 to T. Rowe and DEB 0309369 to T. Rowe and T. Macrini).

Ethics

Origins of samples and permits: Bettongia penicillata, South Australian Museum (SAM); Macropus eugenii, CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems Canberra, colony collected (ACT permit K1606); CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems Animal Ethics Approval 06–36; Phascolarctos cinereus, Adelaide University, field collected (DENWR (SA) license nos K23749/1–25); Sminthopsis macroura, collected from a colony (MAEC (Vic) license no. 06117); Trichosurus vulpecula, collected from a colony (MAEC (Vic) license no. 06118); Monodelphis domestica, collected from preserved specimens at University Museum of University of Tokyo (UMUT), and scans courtesy of T. Rowe and T. Macrini; Ornithorhynchus anatinus, collected from preserved specimens at Queensland Museum and Australian Museum; Tachyglossus aculeatus, collected from preserved specimens at Queensland Museum, Australian Museum and South Australian Museum (SAM).

Data accessibility

The datasets supporting this article have been uploaded as part of the electronic supplementary material.

Authors' contributions

H.E.R.-C. made all virtual reconstructions, co-designed the study, conducted all measurements, conducted all analyses and co-wrote the manuscript. S.W.W. co-wrote the manuscript and assisted with analyses. L.S., L.A.H., C.L. and D.K. provided specimens and co-wrote the manuscript. N.K. assisted with the CT scanning and data processing of specimens and co-wrote the manuscript. V.W. conceived of the study, co-designed the study, co-analysed the data and co-wrote the manuscript. All authors gave final approval for publication.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the UQCent and UQI Scholarships of the University of Queensland to H.E.R.-C.; by Hermon Slade Grant HSF128 and ARC Discovery Grant (DP140102656) to V.W. and S.W.W.; and JSPS Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research 26711023 and 50206596 to D.K.

References

- 1.Sánchez MR. 2012. Embryos in deep time: the rock record of biological development. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kemp TS. 2005. The origin and evolution of mammals. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allin EF. 1975. Evolution of the mammalian middle ear. J. Morphol. 147, 403–438. ( 10.1002/jmor.1051470404) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luo Z-X. 2011. Developmental patterns in Mesozoic evolution of mammal ears. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. S. 42, 355–380. ( 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-032511-142302) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reichert C. 1837. Über die Visceralbogen der Wirbelthiere im Allgemeinen und deren Metamorphosen bei den Vögeln und Säugethieren. Archiv. Anat. Physiol. Wiss. Med. 1837, 120–222. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meckel J. 1820. Handbuch der menschlichen Anatomie. Berlin, Germany: Buchhandlung des Hallischen Waisenhauses. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhaskar S, Weinmann J, Schour I. 1953. Role of Meckel's cartilage in the development and growth of the rat mandible. J. Dent. Res. 32, 398–410. ( 10.1177/00220345530320031401) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anthwal N, Joshi L, Tucker AS. 2013. Evolution of the mammalian middle ear and jaw: adaptations and novel structures. J. Anat. 222, 147–160. ( 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2012.01526.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luo Z-X, Chen PJ, Li G, Chen M. 2007. A new eutriconodont mammal and evolutionary development in early mammals. Nature 446, 288–293. ( 10.1038/nature05627) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rougier GW, Apesteguia S, Gaetano LC. 2011. Highly specialized mammalian skulls from the Late Cretaceous of South America. Nature 479, 98–102. ( 10.1038/nature10591) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bever GS, Rowe T, Ekdale EG, Macrini TE, Colbert MW, Balanoff AM. 2005. Comment on ‘Independent origins of middle ear bones in monotremes and therians’ (I). Science 309, 1492a. ( 10.1126/science.1112248) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rougier GW, Forasiepi AM, Martinelli AG. 2005. Comment on ‘Independent origins of middle ear bones in monotremes and therians’ (II). Science 309, 1492b. ( 10.1126/science.1111294) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meng J, Wang YQ, Li CK. 2011. Transitional mammalian middle ear from a new Cretaceous Jehol eutriconodont. Nature 472, 181–185. ( 10.1038/nature09921) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ji Q, Luo Z-X, Zhang X, Yuan C-X, Xu L. 2009. Evolutionary development of the middle ear in Mesozoic therian mammals. Science 326, 278–281. ( 10.1126/science.1178501) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang YQ, Hu YM, Meng J, Li C. 2001. An ossified Meckel's cartilage in two cretaceous mammals and origin of the mammalian middle ear. Science 294, 357–361. ( 10.1126/science.1063830) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sánchez-Villagra MR, Gemballa S, Nummela S, Smith KK, Maier W. 2002. Ontogenetic and phylogenetic transformations of the ear ossicles in marsupial mammals. J. Morphol. 251, 219–238. ( 10.1002/Jmor.1085) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maier W. 1989. Morphologische Untersuchungen am Mittelohr der Marsupialia. Z. zool. Syst. Evolut.-forsch. 27, 149–168. ( 10.1111/j.1439-0469.1989.tb00340.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rowe T. 1996. Coevolution of the mammalian middle ear and neocortex. Science 273, 651–654. ( 10.1126/science.273.5275.651) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maier W. 1990. Phylogeny and ontogeny of mammalian middle-ear structures. Neth. J. Zool. 40, 55–74. ( 10.1163/156854289X00183) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maier W. 1993. Cranial morphology of the therian common ancestor, as suggested by the adaptations of neonate marsupials. In Mammal phylogeny, vol 1: Mesozoic differentiation, multituberculates, monotremes, early therians, and marsupials (eds Szalay FS, Novacek MJ, McKenna MC), pp. 165–181. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nummela S, Sánchez-Villagra MR. 2006. Scaling of the marsupial middle ear and its functional significance. J. Zool. 270, 256–267. ( 10.1111/j.1469-7998.2006.00126.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosowski JJ. 1992. Hearing in transitional mammals—predictions from the middle-ear anatomy and hearing capabilities of extant mammals. In Evolutionary biology of hearing (eds Webster DB, Fay RR, Popper AN), pp. 615–631. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manley GA. 1972. A review of some current concepts of the functional evolution of the ear in terrestrial vertebrates. Evolution 26, 608–621. ( 10.2307/2407057) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith KK, vanNievelt AFH. 1997. Comparative rates of development in Monodelphis and Didelphis. Science 275, 683–684. ( 10.1126/science.275.5300.683) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Averianov AO, Lopatin AV. 2014. On the phylogenetic position of monotremes (Mammalia, Monotremata). Paleontol. J. 48, 426–446. ( 10.1134/S0031030114040042) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tate A. (dir.). 2014. Your inner reptile. Your inner fish season 1, episode 2. Broadcast on PBS (USA), 16 April. Chevy Chase, MD: Tangled Bank Studios. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luo Z-X. 2011. Negative allometry in ontogeny and evolution of mammalian middle ear in mesozoic mammals. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 31, 148. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuhn H-J. 1971. Die Entwicklung und Morphologie des Schädels von Tachyglossus aculeatus. Abhandlungen der Senckenbergische Naturforschenden Gesellschaft 528, 1–192. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeller U. 1989. Die Entwicklung und Morphologie des Schädels von Ornithorhynchus anatinus (Mammalia, Prototheria, Monotremata). Abh. Senckenb. Naturforsch. Ges. 545, 1–178. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeller U. 1993. Ontogenetic evidence for cranial homologies in monotremes and therians, with special reference to Ornithorhynchus. In Mammal phylogeny, vol 1: Mesozoic differentiation, multituberculates, monotremes, early therians, and marsupials (eds Szalay FS, Novacek MJ, McKenna MC), pp. 95–107. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rich TH, Hopson JA, Musser AM, Flannery TF, Vickers-Rich P. 2005. Independent origins of middle ear bones in monotremes and therians. Science 207, 910–914. ( 10.1126/science.1105717) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin T, Luo Z-X. 2005. Homoplasy in the mammalian ear. Science 307, 861–862. ( 10.1126/science.1107202) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.R Development Core Team. 2014. R: a language and environment for statistical computing, v. 3.2.0. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Warton DI, Duursma RA, Falster DS, Taskinen S. 2012. smatr 3-an R package for estimation and inference about allometric lines. Methods Ecol. Evol. 3, 257–259. ( 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2011.00153.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flores DA, Abdala F, Giannini N. 2010. Cranial ontogeny of Caluromys philander (Didelphidae: Caluromyinae): a qualitative and quantitative approach. J. Mammal. 91, 539–550. ( 10.1644/09-Mamm-a-291.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rowe T. 1997. Comparative rates of development in Monodelphis and Didelphis—response. Science 275, 684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hopson JA. 1966. The origin of the mammalian middle ear. Amer. Zool. 6, 437–450. ( 10.1093/icb/6.3.437) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rougier GW, Wible JR, Hopson JA. 1996. Basicranial anatomy of Priacodon fruitaensis (Triconodontidae, Mammalia) from the Late Jurassic of Colorado, and a reappraisal of Mammaliaform interrelationships. Am. Mus. Novit. 3183, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Phillips MJ, Bennett TH, Lee MS. 2009. Molecules, morphology, and ecology indicate a recent, amphibious ancestry for echidnas. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 17 089–17 094. ( 10.1073/pnas.0904649106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Archer M, Murray P, Hand S, Godthelp H. 1993. Reconsideration of monotreme relationships based on the skull and dentition of the Miocene Obdurodon dicksoni. In Mammal phylogeny, vol 1: Mesozoic differentiation, multituberculates, monotremes, early therians, and marsupials (eds Szalay FS, Novacek MJ, McKenna MC), pp. 75–94. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Beer GR, Fell WA. 1936. The development of the Monotremata. Part III: the development of the skull of Ornithorhynchus. Trans. Zool. Soc. Lond. 23, 1–42. ( 10.1111/j.1096-3642.1936.tb00336.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rowe TB, Macrini TE, Luo Z-X. 2011. Fossil evidence on origin of the mammalian brain. Science 332, 955–957. ( 10.1126/science.1203117) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Herring SW. 1993. Formation of the vertebrate face—epigenetic and functional influences. Amer. Zool. 33, 472–483. ( 10.1093/icb/33.4.472) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harada Y, Ishizeki K. 1998. Evidence for transformation of chondrocytes and site-specific resorption during the degradation of Meckel's cartilage. Anat. Embryol. (Berl). 197, 439–450. ( 10.1007/s004290050155) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting this article have been uploaded as part of the electronic supplementary material.