Abstract

Background/Purpose:

This study aims to analyze the incidence and type of various associated anomalies among infants with extrahepatic biliary atresia (EHBA), compare their frequency with those quoted in the existing literature and assess their role in the overall management.

Materials and Methods:

A retrospective study was performed on 137 infants who underwent the Kasai procedure for EHBA during the past 12 years. The medical records were reviewed for the incidence and type of associated anomalies in addition to the details of the management of the EHBA.

Results:

Of the137 infants, 40 (29.2%) were diagnosed as having 58 anomalies. The majority of patients had presented in the 3rd month of life; mean age was 81 ± 33 days (range = 20-150 days). There were 32 males and 8 females; boys with EHBA had a higher incidence of associated anomalies. Of these 40 patients, 22 (37.9%) had vascular anomalies, 13 patients (22.4%) had hernias (umbilical-10, inguinal-3), 7 patients (12.1%) had intestinal malrotation, 4 patients (6.8%) had choledochal cyst, 1 patient (1.7%) had Meckel's diverticulum, 3 patients (5%) had undergone prior treatment for jejunoileal atresias (jejunal-2, ileal-1), 2 patients (3.4%) had undergone prior treatment for esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula, 2 patients (3.4%) had spleniculi, and 2 patients (3.4%) were diagnosed as having situs inversus.

Conclusions:

The most common associated anomalies in our study were related to the vascular variation at the porta hepatis and the digestive system. The existence of anomalies in distantly developing anatomic regions in patients with EHBA supports the possibility of a “generalized” insult during embryogenesis rather than a “localized” defect. In addition, male infants were observed to have significantly more associated anomalies as compared with the female infants in contrast to earlier reports.

KEY WORDS: Associated anomalies, biliary atresia, vascular variations

INTRODUCTION

Biliary atresia is the most common neonatal cholestatic disorder with a varying incidence of 1:8000-1:18000. The disease is characterized by obliteration or discontinuity of the extrahepatic bile ducts with persistent jaundice in an infant who usually looks well. Most patients with extrahepatic biliary atresia (EHBA) (70-95%) have no associated extrahepatic congenital abnormality and are classified as having “classical” biliary atresia. The remaining cases present in association with one or more extrahepatic congenital anomalies, including polysplenia, portal vein abnormalities, intestinal malrotation, abdominal situs inversus, absence of inferior vena cava, intrapulmonary shunting, asplenia, pancreatic anomalies, and congenital heart disease.[1,2,3,4] These anomalies might be the result of a late intrauterine or early neonatal insult associated with a presumed inflammatory process whereas cases of EHBA with major unrelated congenital anomalies could arise through malformations, disruptions or chromosomal abnormalities. The liver damage may progress despite re-establishment of biliary drainage after corrective surgery.[5,6]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The medical records of 137 patients with EHBA treated by the senior author (VB) in the Department of Pediatric Surgery, AIIMS, New Delhi during the past 12 years were reviewed. Retrospective data were collected from each record including the patient's age at the time of surgery, sex, duration of onset of jaundice, liver function tests, imaging studies, presence of any associated anomalies (polysplenia, hepatic vasculature and portal vein anomalies, intestinal malrotation, situs inversus or congenital heart disease), date of Kasai procedure (KP), liver histology, and postoperative outcome. Imaging evaluation was done with ultrasonography, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, post-priming99 mTc iminodiacetic acid hepatic scan, and peroperative cholangiography.

RESULTS

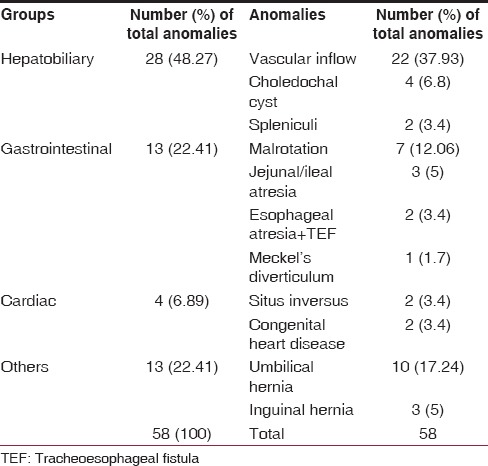

The majority of patients had presented in the 3rd month of life. The mean age was 81 ± 33 days (range = 20-150 days). There were 32 males and 8 females. A total of 40 (29.1%) patients were diagnosed as having 58 anomalies. These anomalies were divided into four groups — hepatobiliary, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and others [Table 1]. Of these 40 patients, 26 patients had hepatobiliary anomalies which included hepatic vascular inflow anomalies in 22 patients, choledochal cyst in 4 patients, and 2 patients had spleniculi. Seven had more than one portal vascular variation. The right hepatic artery arose from the superior mesenteric artery in 7 patients, 10 patients showed early branching of right hepatic artery outside liver parenchyma, in 2 patients right hepatic artery gave a small branch to the left lobe, cystic artery was found to be arising from the left hepatic artery in 2 patients, in 2 patients two cystic arteries were supplying the gall bladder, accessory right hepatic artery was seen in 4 patients, early division of portal vein was seen in 5 patients. Gastrointestinal anomalies were seen in 13 patients (22.4%) and these included intestinal malrotation in 7 patients (12%), jejunoileal atresias (jejunal-2, ileal-1) in 3 patients (5%), 2 patients (3.4%) had esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula, 1 patient (1.7%) had Meckel's diverticulum. Cardiac anomalies included an atrial septal defect in 2 patients and two had situs inversus. Others included umbilical hernias (n = 10) and inguinal hernia (n = 3).

Table 1.

Congenital anomalies associated with biliary atresia

The esophageal atresia and jejunoileal atresia patients had undergone corrective surgeries in the 1st week of life and none of them had received parenteral nutrition. All the patients (n = 7) with malrotation underwent Ladd's procedure simultaneously with KP. Furthermore, patients who had hernias (umbilical/inguinal) underwent hernia repair simultaneously. All infants (n = 4) of EHBA with choledochal cyst had type III biliary atresia and were treated surgically with bilioenteric bypass procedures.

DISCUSSION

Biliary atresia remains one of the most challenging conditions in pediatric surgery. It occurs slightly more often in females than in males (1.4:1), and affects children of all races. The coexistence of EHBA with other congenital anomalies has been widely reported, with an incidence ranging from 10% to 15%. In our study, EHBA occurred as an isolated defect in 70.8% patients and was associated with other anomalies in 29.2% of infants. In larger series of EHBA, either an equal gender distribution or only a slight female predominance was observed.[7,8,9] In our study, not only a higher prevalence of EHBA but also a higher incidence of associated anomalies was seen in boys. This is contrary to other reports.[10,11] Various anomalies including malrotation, liver asymmetry, situs inversus, absent inferior vena cava, preduodenal portal vein, and polysplenia have been reported in association with biliary atresia; teratogenesis during the critical period of fetal embryogenesis of the foregut might be responsible for these anomalies.[12,13] In our series, vascular anomalies at porta hepatis was the most common. The anatomy of the hepatic artery and its variants has been described adequately in literature, but new emphasis was given to this anatomy with the introduction of liver transplantation. Furthermore, a knowledge of the multiple variations helps in avoiding accidents during dissection.

Four patients with atresia of the distal common bile duct had a proximal choledochal cyst and were treated surgically with bilioenteric bypass procedures. The exact etiology and status in various classifications is still controversial.[14,15]

The occurrence of associated anomalies in infants with EHBA might support the hypothesis that the disease represents more than one clinical entity with different causes. In literature, among congenital structural anomalies associated with EHBA, splenic malformations such as polysplenia or asplenia have been known to be very common. Polysplenia syndrome has been reported in 25% of all biliary atresia cases;[16] this might be due to the insult to the bile duct early in gestation at a time coinciding with the development of the spleen and gut rotation. However, it was seen in only two infants (3.4%) in our series. Malrotation of the intestinal tract is the result of a well-defined aberrant sequence of embryological events.[12] In the present series, among gastrointestinal anomalies, malrotation of the intestine was the most frequent anomaly and it was incidentally detected during KP. None of these patients had manifested any symptoms related to intestinal malrotation. In all these patients, Ladd's procedure was performed concomitantly with KP to avoid later manifestations. Technical difficulties were, however, encountered while constructing the Roux en Y loop in the derotated bowel for KP.

The association of EHBA with intestinal atresia is rare. The most frequent form of intestinal atresia associated with EHBA has been reported to be duodenal atresia.[17,18] The association of biliary atresia and duodenal malformation might be presupposed from their common points of embryonic development.[19] The incidence of EHBA in cases of jejunoileal atresia ranges from 0% to 0.5%.[20,21] In our study, there were 2 jejunal atresia and 1 ileal atresia patients. The postulation for the coexistence of biliary atresia and jejunoileal atresia might be bacterial or viral infection in the peri or postnatal period. Furthermore, the coexistence of esophageal and biliary atresia was seen in two patients; the literature has reported this association rarely.[22]

Biliary atresia is reported to occur in 28% of infants born with situs inversus as compared to the 0.01% of the general population and genetic factors were suggested for this coexistence.[19,23] In our series, only two patients (5.5%) showed situs inversus. Reviews conducted by Silveira et al.[24] on 237 biliary atresia patients reported associated structural lesions in 47 patients (19.8%) This finding was confirmed by Carmi et al.[25] in a multicenter study of 251 biliary atresia cases in which 51 children (20.3%) had associated anomalies. Majority of the anomalies in these two series were related to the cardiovascular system. Davenport et al. reported that 25 infants (45%) showed several forms of congenital heart disease and nine infants (16%) required cardiac surgery; of these, the initial operation predated the biliary exploration in 7.[10] In the present series, only two patients showed structural cardiac anomalies; however, echocardiography was not a part of the routine work-up of the patients with biliary atresia and these anomalies might get unnoticed unless looked for specifically.

The existence of anomalies in distantly developing anatomic regions in patients with EHBA supports the possibility of a “generalized” insult during embryogenesis rather than a “localized” defect. The distant anomalies, unless life threatening on their own part, do not affect the surgery for EHBA or the outcome of treatment. However, anomalies of gut rotation and those in and around the porta hepatis can adversely affect the performance of KP and hence the outcome of treatment.

CONCLUSION

In the present study, the incidence of vascular anomalies at the porta hepatis, abdominal wall hernias, malrotation of intestine, and digestive anomalies was much more common as compared to splenic and cardiac anomalies as reported in other studies. Hence, knowledge of vascular patterns can help in avoiding unnecessary complications. In addition, male infants were observed to have a higher incidence of associated anomalies as compared with the female infants in contrast to other reported studies. The presence of anomalies did not affect the timing of the surgery which is important for favorable results.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tanano H, Hasegawa T, Kawahara H, Sasaki T, Okada A. Biliary atresia associated with congenital structural anomalies. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:1687–90. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(99)90645-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asensio Llorente M, López Espinosa JA, Ortega López J, Sánchez Sánchez LM, Castilla Valdez MP, Ferrer Blanco C, et al. First orthotopic liver transplantation in patient with biliary atresia and situs inversus in spain. Cir Pediatr. 2003;16:44–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grosfeld JL, Rescorla FJ, Skinner MA, West KW, Scherer LR., 3rd The spectrum of biliary tract disorders in infants and children. Experience with 300 cases. Arch Surg. 1994;129:513–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1994.01420290059009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davenport M, Kerkar N, Mieli-Vergani G, Mowat AP, Howard ER. Biliary atresia: The King's College Hospital experience (1974-1995) J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:479–85. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90611-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balistreri WF, Grand R, Hoofnagle JH, Suchy FJ, Ryckman FC, Perlmutter DH, et al. Biliary atresia: Current concepts and research directions. Summary of a symposium. Hepatology. 1996;23:1682–92. doi: 10.1002/hep.510230652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischler B, Haglund B, Hjern A. A population-based study on the incidence and possible pre-and perinatal etiologic risk factors of biliary atresia. J Pediatr. 2002;141:217–22. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.126001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kataria R, Kataria A, Gupta DK. Spectrum of congenital anomalies associated with biliary atresia. Indian J Pediatr. 1996;63:651–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02730812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoon PW, Bresee JS, Olney RS, James LM, Khoury MJ. Epidemiology of biliary atresia: A population-based study. Pediatrics. 1997;99:376–82. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.3.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chardot C, Carton M, Spire-Bendelac N, Le Pommelet C, Golmard JL, Auvert B. Epidemiology of biliary atresia in France: A national study 1986-96. J Hepatol. 1999;31:1006–13. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davenport M, Tizzard SA, Underhill J, Mieli-Vergani G, Portmann B, Hadzic N. The biliary atresia splenic malformation syndrome: A 28-year single-center retrospective study. J Pediatr. 2006;149:393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dimmick JE, Bove KE, McAdams AJ. Letter: Extrahepatic biliary atresia and the polysplenia syndrome. J Pediatr. 1975;86:644–5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(75)80185-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang J, Brueckner M, Touloukian RJ. Intestinal rotation and fixation abnormalities in heterotaxia: Early detection and management. J Pediatr Surg. 1993;28:1281–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(05)80313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lilly JR, Chandra RS. Surgical hazards of co-existing anomalies in biliary atresia. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1974;139:49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar A, Gupta AK, Bhatnagar V. Choledochal cyst associated with extrahepatic bile duct atresia. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2005;10:48–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yura J, Hashimoto S, Turuga N. Biliary atresia with intestinal atresia: With special reference to its etiology and the time of onset of the disease. J Pediatr Surg. 1979;11:1361–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davenport M, Savage M, Mowat AP, Howard ER. Biliary atresia splenic malformation syndrome: An etiologic and prognostic subgroup. Surgery. 1993;113:662–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohi R, Koike N, Hanamatsu M. Associated anomalies in infants with hepatobiliary disease. Jpn J Pediatr Surg. 1983;15:595–601. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han SJ, Han A, Choi SH, Oh JT, Hwang EH. Biliary atresia with meconium peritonitis caused by perforation of small bowel atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:1390–3. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.26378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stoll C, Morali A, Leheup B, Lucron H. Extrahepatic biliary atresia with laterality sequence anomalies. Genet Couns. 2001;12:157–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yanagihara J, Nakamura K, Shimotake T, Deguchi E, Iwai N. An association of multiple intestinal atresia and biliary atresia: A case report. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1995;5:372–4. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1066247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asabe K, Yukitake K, Mori T, Mitsudome A, Shirakusa T. Biliary atresia associated with jejunal atresia and a review of the literature in Japan. Asian J Surg. 2005;28:154–7. doi: 10.1016/S1015-9584(09)60283-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samujh R, Srinivasa Rao M, Mahajan JK, Bhattacharjee A, Rao KL. Oesophageal atresia and biliary atresia: A rare association. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004;20:467–8. doi: 10.1007/s00383-004-1178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farmer DG, Shaked A, Olthoff KM, Imagawa DK, Millis JM, Busuttil RW. Evaluation, operative management, and outcome after liver transplantation in children with biliary atresia and situs inversus. Ann Surg. 1995;222:47–50. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199507000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silveira TR, Salzano FM, Howard ER, Mowat AP. Congenital structural abnormalities in biliary atresia: Evidence for etiopathogenic heterogeneity and therapeutic implications. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1991;80:1192–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1991.tb11808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carmi R, Magee CA, Neill CA, Karrer FM. Extrahepatic biliary atresia and associated anomalies: Etiologic heterogeneity suggested by distinctive patterns of associations. Am J Med Genet. 1993;45:683–93. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320450606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]