Abstract

Aim:

Snakebite injuries are common in tropical India among those who are involved in outdoor activities. These injuries results in cellulitis, gangrene at the bite area, bleeding manifestations, compartment syndrome, regional lymphadenopathy, septicemia, hypotension, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) resulting in significant morbidity and mortality. The purpose of this study is to share our experience of multidisciplinary approach in the management of snakebite injuries of the extremities with various treatment modalities including hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) therapy, surgical debridement, and soft tissue reconstruction to provide an effective treatment for snake bite injuries.

Methods:

The study was conducted in the Department of Plastic Surgery, during the period October 2012–December 2014, wherein all the patients who were admitted with snakebite injuries were enrolled and the patients treated in plastic surgery department were included into the study. Out of total 766 patients, there were 323 patients treated with anti snake venom (ASV) and 29 died among the treated patients; 205 patients belonged to pediatric age group.

Results:

Out of 112 patients referred to Department of Plastic Surgery, 50 cases presented with cellulitis, 24 patients with compartment syndrome, and 38 patients were referred for the management of soft tissue cover over the extremities. Among 112 patients, 77 involved the lower extremity and 35 the upper extremity.

Conclusion:

Multidisciplinary approach including hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) therapy improves outcome in the management of snakebite injuries of the extremities.

Keywords: Hyperbaric oxygen therapy, snakebite injury, soft tissue reconstruction, upper and lower extremity

INTRODUCTION

Among 2,000 species of snakes known worldwide, there are about 400 poisonous species. Most of these species belong to the families of Elapidae, Viperidae, Hydrophidae, and Colubridae.[1] Viper bites are more common than other poisonous snakebites in human beings.[2,3] Russell's viper (Viperarusselli) is regarded to be common and considered as occupational hazard for the farming community in south Asia. The World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated that approximately 125,000 deaths occur among 250,000 poisonous snakebites worldwide every year, among which India accounts for 10,000 deaths.[4,5] Snakebite injuries predominantly occur in young working population in rural areas with significant morbidity and mortality. High levels of mortality are experienced in children and the elderly individuals.[6] Pain and swelling at the bitten region inevitably leads to cellulitis and compartment syndrome resulting in systemic toxicity. Although there are a number of studies on snakebite injuries from India, there have been no significant studies on the management of snakebite injuries in this continent. The purpose of the study is to share our experience in the management of snakebite injuries of the extremities with various treatment modalities including hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) therapy, surgical debridement, skin grafting, local, or distant flaps to provide an effective treatment from plastic surgeons' perspective.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted in Jubilee Mission Medical College and Research Institute, Thrissur in the Department of Plastic Surgery, Jubilee Institute for Surgery of Hand, Aesthetic and Microsurgery during the period October 2012–December 2014, wherein all the patient who were admitted with snakebite injuries were enrolled and the patients treated by plastic surgery department were included into the study. Out of total 766 patients, there were 323 patients treated with ASV and 29 died among the treated patients; 205 patients belonged to pediatric age group. Out of 112 patients referred to Department of Plastic Surgery, 50 cases presented with cellulitis, 24 patients with compartment syndrome, and 38 patients were referred for the management of soft tissue cover over the extremities. Among 112 patients, 77 were involving the lower extremity and 35 were involving the upper extremity.

All the patients received tetanus toxoid. The cases of snakebite was assessed by emergency physician, classified the snakebite injuries as poisonous and nonpoisonous clinically. Antisnake venom (ASV) was administered accordingly. Antibiotics and diuretics were administered, as indicated. Transfusions of blood and blood products were given to the indicated patients. Patients were admitted in Medicine and Pediatric Departments and thereafter referred to plastic surgery department if suspected for any cellulitis, compartment syndrome, or soft tissue loss. When referred to plastic surgery department, patients with cellulitis and compartment syndrome were subjected to HBO therapy. A session of six HBO therapy, one session extending to 90 min for 6 days was administered. Patients manifesting soft tissue necrosis were initially subjected to surgical debridement followed by six sessions of HBO therapy. The patients were followed-up thereafter.

OBSERVATION AND RESULTS

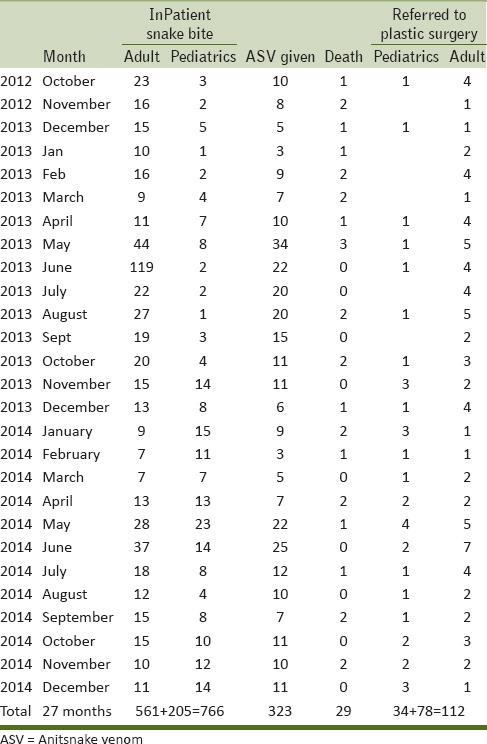

Out of total 395 patients during the period October 2012–December 2014, there were 323 patients treated with ASV [Table 1]. Two hundred and five were pediatric age group and 561 patients were adult. There were 29 mortalities experienced, eight patients were in pediatric age group and 21 were adult. One hundred and twelve patients were referred to the Department of Plastic Surgery, 38 belonged to the pediatric age group and 78 were adults. Among 112 patients, 50 cases presented with cellulitis (11 pediatric and 39 adults), 24 patients with compartment syndrome (nine pediatric and 15 adults), and 38 patients (13 pediatric and 25 adults) were referred for the management of soft tissue cover over the extremities [Table 2]. Among these 112 patients, 77 were involving the lower extremity and 35 were involving the upper extremity. Patients treated for cellulitis and compartment syndrome were managed with ASV, antibiotics, analgesics, antiedema measures, and HBO therapy. There was no need for fasciotomy among the patients who suffered impending compartment syndrome. Soft tissue defects were managed by skin grafting and flap covers with HBO therapy included in the treatment regime.

Table 1.

Admission of patients with snakebite injuries during the period October 2012-December 2014

Table 2.

Number of pediatric and adult patients referred to plastic surgery department with snakebite injuries

Case 1

A 5-year-old boy was admitted with snakebite envenomation to the right leg lower third region presented with compartment syndrome of the right leg and foot region [Figure 1a and b]. HBO therapy was administered for six sessions following admission. Patient recovered from the compartment syndrome without any surgical intervention [Figure 1c].

Figure 1.

Compartment syndrome of the right leg and foot region: (a) Lateral view and (b) anterior view. (c) Picture showing resolved compartment syndrome after six sessions of hyperbaric oxygen therapy

Case 2

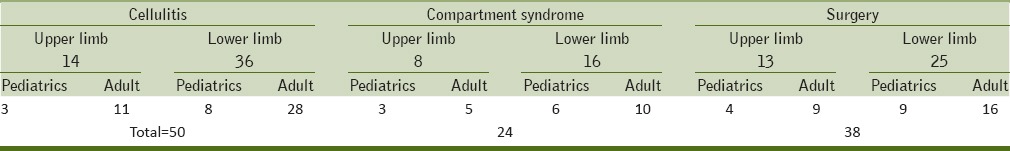

A 32-year-old female presented with soft tissue loss over the right index finger middle phalanx level radial aspect measuring 3 cm × 2 cm × 1 cm exposing the flexor tendon with surrounding unhealthy tissue [Figure 2a and b]. Wound debridement was done and the soft tissue defect was reconstructed with cross finger flap from the right middle finger. Donor area was covered with skin graft [Figure 2c and d]. Postoperative period was uneventful.

Figure 2.

Soft tissue loss right index finger radial aspect: (a) Anterior view and (b) lateral view. Cross finger flap cover following debridement: (c) Anterior view and (d) posterior view

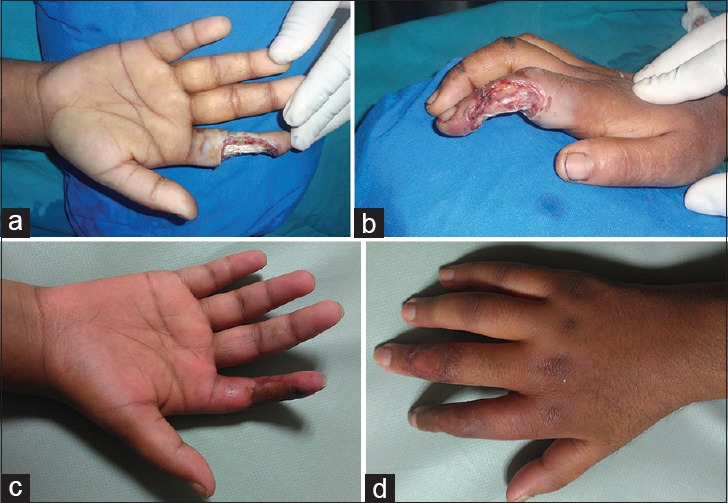

Case 3

A 27-year-old female presented to plastic surgery department with soft tissue loss measuring 3 cm × 2 cm × 1 cm over the dorsum of the right thumb with slough and necrotic tissue [Figure 3a]. Wound debridement done. First dorsal metacarpal artery flap was used to cover the soft tissue defect. Donor area was covered with skin graft. Postoperative period was uneventful [Figure 3b and c].

Figure 3.

(a) Soft tissue loss dorsum of the right thumb following snakebite injury. (b) Planning for first dorsal metacarpal artery (FDMA) flap for right thumb dorsum. (c) Picture following reconstruction of the soft tissue defect

Case 4

An 8-year-old boy admitted with snakebite envenomation of the dorsum of right foot presented with compartment syndrome and discoloration at the bite site [Figure 4a]. HBO therapy was administered for six sessions following admission and sequential evaluation done [Figure 4b–d]. After demarcation of the nonviable tissue, debridement and skin grafting was done [Figure 4e].

Figure 4.

(a) Day 1 picture of compartment syndrome and discoloration at the bite site; right foot dorsum. (b) Day 2 picture of right foot dorsum started on hyperbaric oxygen therapy. (c) Day 3 picture of right foot dorsum on hyperbaric oxygen therapy. (d) Day 5 picture of right foot dorsum started on hyperbaric oxygen therapy with resolving edema. (e) Picture of right foot dorsum following skin grafting on the debrided necrotic region

DISCUSSION

There is a high incidence of mortality and morbidity due to snakebite injuries in Asian countries. Males, predominantly the younger population (20–40 years) were more involved and more commonly affected among the victims than females, as they are most commonly involved in outdoor activities. Bhat[3] noticed an 80% incidence of snake envenomation in this age group. Extremities are more commonly involved when compared to other regions. The most common symptoms observed are pain and swelling at the bitten region. Systemic and local signs of envenomation appear within few hours. Some systemic signs like bleeding, hypotension, cardiotoxicity, and nephrotoxicity may require immediate attention. Local signs like tissue edema, compartment syndrome, and tissue necrosis may require surgery and may even necessitate amputation.[7,8]

In our institution, snake envenomation is initially treated with intensive care measures by emergency medicine specialist. Antivenom administration can reduce progression of initial tissue damage, but it cannot control the acute tissue damage like inflammation, tissue edema, compartment syndrome, and tissue necrosis.[7] Extremities are more prone for manifesting tissue edema, compartment syndrome, and tissue necrosis as the intermuscular fascial septa limits the tissue space, which in turn impairs circulation to the affected region. The severity of the disease may be related to the size of the patient and individual sensitivity to the venom, the species and size of the snake, the location, depth, and number of bites.[9] Venom deposition into different planes of tissue results in wide range of manifestations from tissue edema to cellulitis, compartment syndrome, and tissue necrosis.[10] Inflammatory process when left uncontrolledmay result in tissue necrosis. Harshavardhan et al.,[11] noted that the incidence of nephrotoxicity increases proportionately to the cellulitis and gangrene at the bite site. Antivenom therapy only may not reverse the causes of local tissue damage, since the inflammation occurs by a variety of mechanism.[12] True bacterial cellulitis is uncommon, even though inflammation induced by snakebite injuries often mimics infection.[13] There is always difficulty to decide whether an envenomated extremity is inflamed or infected and this may lead to unnecessary medical interventions.[14] At the zone of envenomation, tissues may be nonviable with irreversible damage which may not respond to intervention. The next zone outward consists of variably injured tissues that may recover if the process of inflammation is controlled. Most of our therapeutic maneuvers are focused on this penumbra of marginal tissue in an attempt to maximize recovery of the tissue with doubtful viability. Finally, the third outer zone of minimally injured tissues may be at risk from the processes of secondary injury resulting from delayed, physiologic inflammatory responses to snakebite injury. Sometimes the quantity of tissue loss and destruction caused by secondary injury can be more than the actual loss from the primary event that had occurred due to snake envenomation. Hence, there is a need for interventions which impedes the progress of inflammation, preserve marginal tissue under risk, prevention of ischemia, and hypoxic advancement of the injured tissue.

There are still some controversies regarding the need for fasciotomy in compartment syndrome following snakebite injuries. Snakebite envenomation can produce pain, swelling, induration, paresthesias, color changes, absent pulse, and tenderness in the involved extremity, mimicking the initial signs of compartment syndrome. However, true compartment syndrome in snakebite injuries is less common.[15] Tanen et al.,[16] demonstrated only 8/236 (3.4%) patients who received a fasciotomy or digital dermotomy for compartment syndrome. Measurement of compartment pressure of the involved limb prior to consideration of fasciotomy is always recommended. Only when there is an increase of intracompartmental pressure up to 30–45 mmHg, it becomes an absolute indication for fasciotomy.[17,18] Measurement of intracompartmental pressure is not always feasible in many medical centers in India, and the diagnosis of compartment syndrome is still based on clinical standards. Parrish[19] described that 21.2% of snakebites involve fingers. Compartment pressure measurement may not be possible in such cases and the diagnosis of compartment syndrome can be made only on clinical grounds. Some authors support early fasciotomy in the treatment of all cases of snakebite envenomation to avoid the consequence of compartment syndrome.[20] However, early fasciotomy is not without complication. It may result in disfiguring scars, contractures, nerve damage, and significantly lengthening the course of treatment.[10]

In early compartment syndrome, HBO therapy may reduce the penumbra of cells at risk for delayed necrosis and secondary ischemia.[21] HBO therapy may be included in the treatment regime of snakebite injuries either as an adjunct for surgical intervention or as a primary tool in the treatment of compartment syndrome or cellulitis.[22] Breathing of 100% oxygen under increased ambient pressure shows prevention of reperfusion injury, reduction of tissue edema, and reversal of sub-lethal tissue damage.[21,22] The effect of HBO therapy on the local reaction in snakebite injuries and burns' victims exceeded the one usually seen when treating a trauma-induced inflammation and compartment syndrome as true bacterial cellulitis is uncommon in these cases.

In our series conducted in plastic surgery department, 50 patients were treated for cellulitis and 24 patients for compartment syndrome. After the initial treatment with ASV and antibiotics, HBO therapy sessions were initiated. Six sessions of HBO therapy sessions were administered, each session extending for 90 min with pressure ranging from 1.8 to 2.4 ATA.[22] The sessions were extended according to the clinical progress of the disease. The same regimen was followed in case of compartment syndrome. The sessions were extended in chronic wound.[22] In our sessions of therapy, we did not experience any complications related to hyperbaric oxygenation. Fasciotomy was not required for the group of patient suffering from compartment syndrome. According to our experience, hyperbaric oxygenation is helpful in the management of impending compartment syndrome which may require a fasciotomy later. It is difficult to explain if the patients were not treated with HBO, the local reaction would have progressed to compartment syndrome or tissue necrosis. However in the hands of expertise team treating snakebite injuries, HBO therapy seems to be an effective tool when the patient's clinical condition is in-between conservative management and definitive surgical intervention. Considering the decreased rates of adverse effects of HBO therapy and its usefulness in clinical situations, it could be justified that the empiric use of HBO therapy may be considered in such cases.

In our unit, HBO is administered in a Monoplace chamber. We have always had a parent accompany the child in our Monoplace chamber to provide reassurance for small children and there were no children who refused treatment. As an adjunct to ASV, antibiotics, and surgery; HBO therapy can significantly decrease costs and complications.[23] Vasoconstriction following hyperoxygenation reduces tissue edema and tissue swelling while ensuring adequate oxygen delivery, and is thus useful in snakebite injury wounds.

Primary treatment is antivenom administration and ICU care is mandatory to these patients, if they are unstable. The treatment of soft tissue complications are dealt with following critical stabilization of the patient. The variation in tissue damage according to the type of snake could not be assessed in these injuries as the only evidence was the bite marks. However, further studies are required for specific treatment protocol with different types of venomous snakes. As the degree of cellulitis and its severity varied from patient-to-patient and also the timing of referral was not uniform with regard to days from the bite, there was no specific standardized date where we can say as the starting point of administration of HBO therapy. Six sessions is needed for some tangible decrease in swelling and often when the child is able to move the toes, we terminate the HBO therapy. Assessing sensory loss may not be possible in small children, and hence we terminate treatment based on decrease in girth of the limb and also with the movement of the toes. If sufficient softness of the tissue in the affected region was not achieved, a few more sessions were administered. If so usually the treatment sessions were extended for 1more week. HBO therapy after surgical debridement, soft tissue cover is beneficial in terms of reducing edema of the inflamed operated site. Hence, we prefer HBO therapy atleast six sessions in those patients who underwent surgery if they are ready to afford for the treatment. Prior to these cases reaching HBO therapy, majority was treated by the general surgeon, who used glycerin magsulf dressings and if not improved often did fasciotomies. The exact incidences of fasciotomies for snakebite injuries are not known. A course of hyperbaric treatment at 2.4 ATA for 90 min for 6 days and the cost in comparison to fasciotomy, surgical charges, postsurgical dressings, and extending patient care all add up to costs that surpass this amount. No studies have been reported till now to prove that the utility of HBO by comparing with control. HBO therapy is a useful adjunct in treatment of snakebite and helps decrease tissue damage and can often avoid surgical decompression of an impending compartment syndrome. HBO therapy is useful in preventing tissue damage due to inflammation, but not an established one for tissue necrosis. HBO therapy and debridement has its own separate roles to play in such injuries, and hence requiring a multidisciplinary approach.

At our institution, we have developed a strategy to overcome these difficulties and manage these patients with a multidisciplinary approach that maximizes tissue perfusion and oxygenation, allowing for surgical correction of such injuries. Postoperatively six sessions of HBO therapy sessions were administered to obtain a better outcome in surgical patients. Further investigations about the usefulness of HBO therapy for such clinical condition might be warranted.

CONCLUSION

Snakebite injuries of the extremities are more common in Asian population. Immediate medical care by emergency medicine specialist is almost necessary. Majority of the patients with snakebite injuries manifests cellulitis, compartment syndrome, and tissue necrosis. Various treatment modalities including HBO therapy, fasciotomy, surgical debridement, and soft tissue cover may be required to provide an effective management of such injuries. HBO therapy as an adjunct is effective in the management of snakebite injury.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Homrany M. Acute renal failure following snake bites: A case report and review. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 1996;7:309–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basu J, Majumdar G, Dutta A, Sengupta SK, Kundu B, Dass S, et al. Acute renal failure following snake bites (viper) J Assoc Physicians India. 1977;25:883–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhat RN. Viperine snake bite poisoning in Jammu. J Indian Med Assoc. 1974;63:383–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chippaux JP. Snake-bites: Appraisal of the global situation. Bull World Health Organ. 1998;76:515–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chugh KS, Pal Y, Chakravarthy RN, Datta BN, Mehta R, Sakhuja V, et al. Acute renal failure following poisonous snakebite. Am J Kidney Dis. 1984;4:30–8. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(84)80023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gold BS, Dart RC, Barish RA. Bites of venomous snakes. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:347–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra013477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warrell DA, Ormerod LD, Davidson NM. Bites by puff-adder (Bitis arietans) in Nigeria, and value of antivenom. Br Med J. 1975;4:697–700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5998.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lavonas EJ, Tomaszewski CA, Ford MD, Rouse AM, Kerns WP., 2nd Severe puff adder (Bitis arietans) envenomation with coagulopathy. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2002;40:911–8. doi: 10.1081/clt-120016963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Russell FE. Snake venom poisoning in the United States. Annu Rev Med. 1980;31:247–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.31.020180.001335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gold BS, Barish RA, Dart RC, Silverman RP, Bochicchio GV. Resolution of compartment syndrome after rattle snake envenomation utilizing non-invasive measures. J Emerg Med. 2003;24:285–8. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(02)00762-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LH, AJ L, HL T, BR H, Metri SS. A study on the acute kidney injury in snake bite victims in a tertiary care centre. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:853–6. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/5495.2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ownby CL, Colberg TR, Odell GV. In vivo ability of antimyotoxin a serum plus polyvalent (Crotalidae) antivenom to neutralize prairie rattlesnake (Crotalus viridis viridis) venom. Toxicon. 1986;24:197–200. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(86)90122-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark RF, Selden BS, Furbee B. The incidence of wound infection following crotalid envenomation. J Emerg Med. 1993;11:583–6. doi: 10.1016/0736-4679(93)90313-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scharman EJ, Noffsinger VD. Copperhead snakebites: Clinical severity of local effects. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;38:55–61. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.116148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curry SC, Kraner JC, Kunkel DB, Ryan PJ, Vance MV, Requa RK, et al. Noninvasive vascular studies in management of rattlesnake envenomations to extremities. Ann Emerg Med. 1985;14:1081–4. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(85)80926-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanen D, Ruha A, Graeme K, Curry S. Epidemiology and hospital course of rattlesnake envenomations cared for at a tertiary referral center in Central Arizona. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:177–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb01284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garfin SR, Castilonia RR, Mubarak SJ, Hargens AR, Russell FE, Akeson WH. Rattlesnake bites and surgical decompression: Results using a laboratory model. Toxicon. 1984;22:177–82. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(84)90018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schexnayder SM, Schexnayder RE. Bites, stings and other painful things. Pediatr Ann. 2000;29:354–8. doi: 10.3928/0090-4481-20000601-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parrish HM. Poisonous Snakebites in the United States. New York: Vantage Press; 1980. pp. 1–460. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glass TG., Jr Early debridement in pit viper bites. JAMA. 1976;235:2513–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.235.23.2513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rainer PP, Kaufmann P, Smolle-Juettner FM, Krejs GJ. Case report: Hyperbaric oxygen in the treatment of puff adder (Bitis arietans) bite. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2010;37:395–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhutani S, Vishwanath G. Hyperbaric oxygen and wound healing. Indian J Plast Surg. 2012;45:316–24. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.101309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bouachour G, Cronier P, Gouello JP, Toulemonde JL, Talha A, Alquier P. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in the management of crush injuries: A randomized doubleblind placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Trauma. 1996;41:333–9. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199608000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]