Abstract

Quality of life (QOL) is a key clinical outcome in patients with lung cancer because of the debilitating nature of the disease and its treatments. In recent years, advances have been made in the assessment of QOL via patient-reported outcomes. A brief history of the evolution of QOL measures in oncology clinical trials and practice is given with specific reference to early-stage lung cancer. The role that QOL can play as a prognostic factor, especially among lung cancer patients, is delineated. The most commonly seen symptoms among lung cancer patients are listed. This review is intended to provide the clinical researcher with a summary of the alternative measures that are both valid and reasonable to consider when assessing QOL in early-stage lung cancer patients. Suggestions for QOL assessment in both a research setting and clinical environment are considered. A review of the most popular QOL assessments in general application to lung cancer and disease-specific measures is provided. An algorithm for selecting appropriate QOL assessments for lung cancer clinical research is provided. The primary conclusion from this work is that scientifically sound investigations into the QOL of early-stage lung cancer patients are feasible and encouraged so that the care of these patients can be optimized.

Keywords: Lung cancer, quality of life, clinical significance

THE IMPORTANCE OF QUALITY OF LIFE FOR LUNG CANCER PATIENTS

Lung cancer accounts for more than 1 of every 4 deaths due to cancer.1 The number of deaths from lung cancer exceeds the total combined number for the next 3 most common causes of cancer deaths: breast, colorectal, and prostate. Even among patients with early-stage lung cancer, the morbidity and mortality implications have long been established as daunting.2,3

Quality-of-life (QOL) issues for patients with lung cancer in general have been a major focus with the reality that the vast majority of patients will live a relatively short period with significant impairments.3 Obvious physiologic impacts such as cough, shortness of breath, dyspnea, pain, and fatigue are combined with prevalent feelings of anxiety, situational depression, and disruption of familial and social relationships.4,5 A recent review of North Central Cancer Treatment Group lung cancer clinical trials indicated that the most prevalent QOL-related issues involved nausea, vomiting, fatigue, anorexia, dyspnea, and diarrhea.

This presents a complex set of variables for the clinician and clinical researcher to address alongside the treatment of the disease itself.

The QOL issues for early-stage lung cancer differ only in degree rather than the nature of the insults to patient well-being and activities of daily living.6 Although patients with early-stage disease have a longer expected survival, the impact on their QOL is similar to that experienced by advanced cancer patients.7 Bezjak and colleagues8 present an excellent example of a completed protocol, analysis, and interpretation of QOL specifically for early-stage lung cancer. Yan et al9 recently published a systematic review of trials involved in early-stage lung cancer and detailed the QOL issues faced by these patients. Several studies have been done attempting to improve patient QOL in this patient population.10,11 Cella and Patel10 have tested numerous ways of improving QOL including pharmacological, biological, and psychosocial approaches. Thompson et al11 presented a systematic review of the noninvasive nursing interventions for improving well-being in lung cancer patients and found evidence to recommend nursing-led programs for symptom control such as breathlessness.

THE EVOLUTION OF QOL ASSESSMENT IN CANCER

Fortunately, there are guidelines and established procedures to undertake sound research in QOL assessment.12,13 Multiple international efforts have produced techniques to resolve issues surrounding missing data and psychometrics so that it is now verifiable that QOL measures are scientifically sound.14–17 Moreover, a review by Hahn et al18 found that the precision of QOL variables was comparable or better than most other clinical variables. In particular, there have been advances in the science surrounding patient-reported QOL assessment via patient-reported outcomes (PROs). Many QOL instruments date back to the 1970s,19 and yet there are now several newer PRO instruments that have been specifically designed to more precisely measure QOL according to the site of disease (e.g., European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer [EORTC] Quality of Life Questionnaire [QLQ] for lung, breast, head and neck, esophagus, etc.20) and according to the type of treatment (e.g., Radiation Therapy Oncology Group QOL tool for radiation therapy).21 In addition to having more instruments, there are more baseline data. Indeed, the annual number of publications in the field of QOL and oncology has risen from a mere 32 articles in 1973 to nearly 1000 by 1990 and 5444 by 2004.22 An end result of this literature is that there are now in excess of 20,000 PRO-based assessments available, and normative data now exist for a large number of assessments such as the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT), EORTC, and Medical Outcomes Survey–Short Form series of measures.23 For example, by testing large numbers of patients and individuals, using a 10-point Linear Analogue Self-assessment (LASA) scale, we can now identify baseline differences in QOL. To this point, we know that healthy individuals score 8 on the 0- to 10-point scale, advanced cancer patients score between 6 and 7.5, and patients newly diagnosed with cancer score between 5 and 6.24 For any given cancer, we now have considerable normative data for both short- and long-term QOL-related PROs.25

During the evolution of QOL assessment, a key question arose asking whether measuring toxicity via Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) clinician ratings is sufficient and redundant with measuring QOL. Studies have shown that the concordance between patient and clinician rating of toxicities is weakly correlated.26,27 The CTCAE is useful to detect serious adverse events as designed for safety monitoring. Quality-of-life PROs, however, are more sensitive than the CTCAE and allow toxicity and QOL issues to be identified earlier to intervene prophylactically. This fact was recognized by the National Cancer Institute funding of an initiative to develop a patient-reported version of the CTCAE.28

The existence of large volumes of normative data naturally led to the development of accepted standards for defining the clinical significance of PROs. Starting in 2002, QOL researchers worked in tandem in attempting to arrive at consensus for definitions of clinical significance for QOL measures.29 Ultimately, work by these investigators led regulatory agencies to define what is meant by “clinical significance” in PRO-based research of QOL-related domains.30–34 A framework for defining clinical significance in terms of effect sizes (the size of the differences observed between treatments) has seen extensive use in clinical trials.31,32 Tying the clinical significance to another outcome such as performance status as an anchor to estimate a clinically significant benefit is also sometimes used.30 The encouraging finding from this extensive body of research is that regardless of the methodological approach used, the definition of what is clinically significant in terms of QOL assessments is consistently of the same order of magnitude.34,35 For example, under virtually any circumstance it has been demonstrated that a half- SD shift in a QOL outcome is clinically nonignorable.31,34–36 Returning to the LASA normative data example above, it is now accepted, based on initial work and verified by others, that a 2-point difference in LASA scores is considered clinically nonignorable, and a score of 5 or less is indicative of a need for clinical intervention.36,37

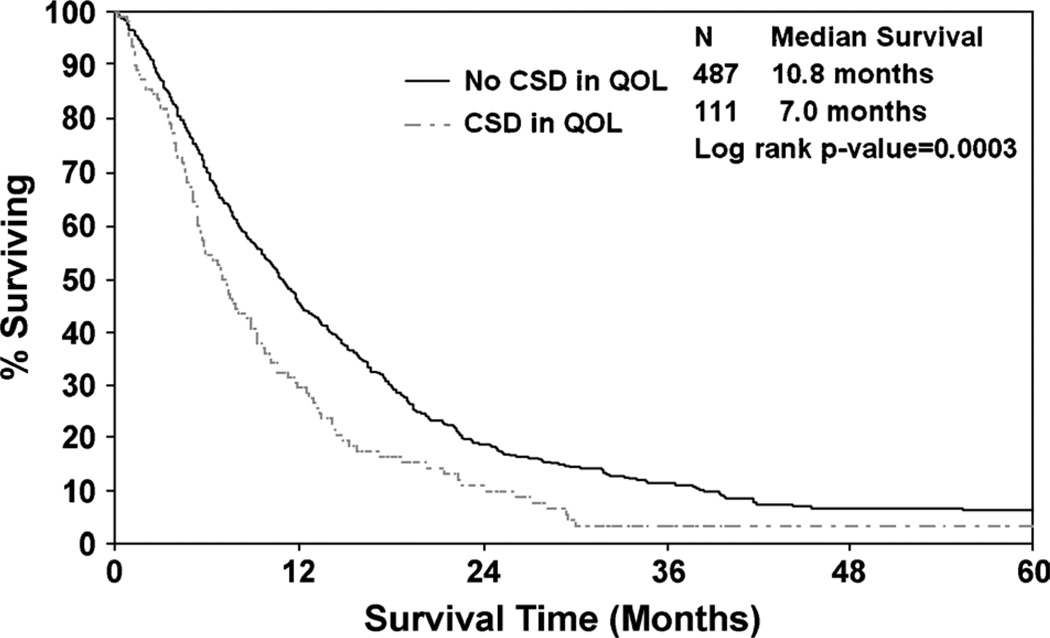

Most recently, the emergence of evidence that QOL is a prognostic variable for cancer patient survival has led to more routine incorporation into clinical research. The evidence goes back as far as a study by Degner and Sloan38 in 1995 wherein symptom distress was seen to be prognostic for survival for a cohort of newly diagnosed ambulatory lung cancer patients. A report by Gotay et al39 illustrates this point as this review of 39 clinical studies demonstrated a consistent and significant relationship between at least 1 PRO and survival in multivariate analysis in 36 of the 39 studies. A review over a 20-year period ending in 2006 found more than 100 clinical trials wherein QOL-related PROs were found to be prognostic for survival in cancer patients.40 This effect was seen specifically among lung cancer patients in a study by Huschka et al26 and displayed in Figure 1. Depicted is a pair of survival curves for patients who report a clinically significant deficit in QOL versus those who do not report a deficit at baseline before treatment is initiated. A difference in median survival of more than 3 months was observed, which is more profound of a difference in median survival than most anticancer treatments for lung cancer. As a result of this work, the North Central Cancer Treatment Group decided in 2009 to incorporate overall QOL and fatigue as baseline assessments in all of their clinical trials to be used either as stratification variables or covariates in survival analyses. Another study by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group recently confirmed these findings, indicating that QOL actually superseded other more accepted prognostic variables for survival in advanced lung cancer.41

FIGURE 1.

QOL as a prognostic indicator of survival among lung cancer patients.

As evidence has mounted indicating that QOL-related PROs can serve as key endpoints in clinical trials, the next logical question is whether QOL PROs can serve as key clinical indicators in practice. A number of efforts have been attempted to incorporate QOL into routine oncology clinical practice.42–46 Higginson and Carr42 described the various advantages of incorporating QOL into clinical practice. Chang et al43 used the FACT-Lung Cancer (FACT-L) QOL assessment in a clinic of lung cancer. Although physicians were generally supportive of the effort, the complexity of the information provided was identified as a barrier to routine use of QOL data. Detmar and colleagues44 demonstrated in a randomized clinical trial that incorporating QOL assessments into clinical practice can indeed facilitate communication. Taenzer et al46 further did a clinical study of a lung cancer outpatient practice that indicated patient well-being and physician behavior could be impacted by the availability of electronic screening for QOL-related issues. Both these studies found that physicians were in need of clinical pathways to facilitate the use of QOL data in their practice. Velikova et al45 in a pair of studies provided evidence that not only could communication between physicians and patients be improved but that also patient well-being could actually be improved.

Some PRO-based assessments have already been adopted in the clinic. For example, the management of pain in surgical patients swiftly shifted away from provider-based assessments toward patient-based assessments following the introduction of the linear pain scale assessment tools. It is now routine and commonplace for patients to rate their own pain and for that information to serve as the basis for pain management. Numerous clinical applications are being tested including routine assessment within oncology practice at the Mayo Clinic beginning in 2010 of overall QOL and fatigue at the same time that pain is assessed for each patient upon intake. Anecdotal evidence has already indicated that including these simple single-item measures of QOL has practice-changing impact for both clinicians and patients.

POPULAR QOL ASSESSMENTS FOR EARLY-STAGE LUNG CANCER

There have been numerous reviews of available QOL measures for lung cancer published elsewhere. Bottomley et al25 did a review of these measures in 2003 and at the time of this writing has a manuscript in press at the Journal of Clinical Oncology updating his previous work, so they will not be repeated here. Instead, a few key ones will be highlighted, and then we will provide a general approach one should take to choosing the specific QOL measures for specific applications. The main message to be imparted from this work is that there exists a large number of alternative measures for assessing QOL in lung cancer patients who have been demonstrated to have the requisite theoretical framework and psychometric properties so that investigators can use them with confidence.47 All of these measures can be viewed at www.qolpro.org with associated reference material with the user ID form_banker and the password iloveforms08.

The majority of lung cancer trials use 1 of 3 disease-specific measures: the EORTC-QLQ–Lung Cancer (EORTC-QLQ-LC13) module,48 the FACT-L49 module or the Lung Cancer Symptom Scale assessments.50 The EORTC-QLQ-LC13, FACT-L, and Lung Cancer Symptom Scale are composed of 13, 17, and 9 items, respectively, which produce a single summative score. Individual questions may be drawn from each of these modules for use in specific trials, but the items must then be used only as separate, individual variables as the validity of the summative score is compromised.

Typically alongside disease-specific measures, general indication of overall QOL is included in clinical trials.51 The most common measures seen in the arena of lung cancer are the parent questionnaires of the EORTC and FACT measures, one of the Medical Outcomes Survey–Short Form measures,52 or a series of single-item LASA items.53 All 4 of these measures will provide scientifically sound estimates of overall QOL along with the major subdomains such as physical and mental function.54 The LASA measures have become the most often used measures for assessing QOL in cancer control trials supported by the National Cancer Institute.47 Furthermore, these particular measures of overall QOL and domains have demonstrated preliminary evidence for a relationship between QOL and genetic variables.55

SELECTION OF ASSESSMENT MEASURES FOR EARLY-STAGE LUNG CANCER

Efficace et al17 set out a general algorithm for choosing QOL measures as part of a monograph on solutions for assessing QOL in cancer patients. Basically the algorithm is as follows:

Define the clinical outcomes, both general to cancer patients and specific to the patient population under study, that are expected to change over time, be different between patients, or impact treatment outcome.

With literally thousands of QOL measures, it is unlikely that you will be studying an area that has no previously developed and validated QOL measure. It is likely that most of the concepts you want to cover will be contained within existing measures and that there will be a small number of disease- or treatment-specific concepts that are not covered. Inspect general and disease-specific existing measures for adequacy of covering the concepts in your list from step 1.

-

Choose the most appropriate existing measure that has the smallest number of items for you to meet your goals.

Choose a general measure if you want to be able to compare your sample to other patient populations.

Choose a disease-specific measure or module that covers the majority of issues that you have listed.

Construct study-specific items that are not contained in any existing measure. In constructing these items, you must keep in mind that these are exploratory and intended to answer a specific detail or question that will serve as a supplementary secondary endpoint. If these items can be understood by a single word or simple phrase by patients, they can be put into a numerical analog response format akin to the work of Cleeland and others.56

- Test drive the set of items by your colleagues and a few volunteer patients, if possible asking 3 specific questions:

- Did any item not apply to you?

- Did any item upset or confuse you?

- Did the questions cover all the important things regarding your QOL?

An example: Suppose you want to assess QOL of patients receiving 1 of 2 alternative treatments for early-stage lung cancer. The treatments have different toxicity profiles, and it is unlikely that survival will be markedly different between the 2 treatments, although of course that will be tested. The primary comparative effectiveness conclusion will be made based on the differences in QOL-related domains. In previous trials, 1 drug is related to toxicities including peripheral neuropathy, pain, and neutropenia, whereas the other incurs gastrointestinal issues such as diarrhea and nausea.

Step 1. Our list of symptoms includes nausea, diarrhea, pain, neutropenia, and peripheral neuropathy. Neutropenia typically is related to general reported deficits in fatigue and overall QOL, so we can expect these to change over time and impact patient compliance and treatment efficacy.

- Step 2. Consider alternative general measures of QOL. The EORTC, FACT, SF, and LASA series of forms will provide summary measures for overall QOL with subscales, and all have been previously validated for use in lung cancer patient populations including early-stage disease. Many of the items in these forms will not apply to each patient as they were designed for more global populations. In the case of the SF measures, they were designed and perform optimally when applied to healthy populations, although they have seen extensive use in cancer patients. The number of items ranges from 5 (LASA) to 30 (EORTC), with varying level of detail.

- Step 3a. At this point, it is up to the investigator how much detail he/she wants regarding overall QOL and its domains. Let us decide upon the LASA series for this study as we are more interested in the disease-specific outcomes for detail than detail on overall QOL, so a simple indication of each QOL domain is sufficient.

- Step 3b. Inspection of the 4 lung cancer-specific modules mentioned above for this example indicates that all have items for nausea, fatigue, and pain.

Step 4. None of the generic or disease-specific measures chosen have items for peripheral neuropathy. Gastrointestinal issues such as diarrhea are not detailed either. In this case, we must turn to using a supplementary measure to capture these important aspects of QOL in this clinical setting. For diarrhea, we might turn to the use of a developed module specifically to assess bowel function in cancer patients such as the Mayo Bowel Function Questionnaire or the FACT-D.57 Peripheral neuropathy can be assessed using items developed by the North Central Cancer Treatment Group specifically for this purpose. We might also consider supplementing these established items with protocol-specific items (such as “Did our new nursing-led initiative to control your breathlessness improve your QOL on a 0- to 10-point scale from ‘not at all’ to ‘a great deal’?”). These latter unvalidated supplementary protocol-specific items often provide rich data to detail aspects of the patient experience, which might otherwise go unobserved. As they are all “one off ” items, their primary purpose is descriptive and supplementary and should not be used as primary or key secondary endpoints.

SUMMARY

The key aspect of the state of the science in QOL assessment is that these measures have now been well studied and established to be as reliable, valid, and reproducible as any other laboratory biomarker.38 Hence, given that we now know these valid PRO assessments can identify vulnerable subpopulations reliably, and we are beginning to uncover the biological processes that lead to deficits in PRO QOL domains, we can begin to think of these measures as just another surrogate endpoint biomarker. The source of the surrogate endpoint biomarker may be the patient’s cognitive report rather than a laboratory specimen, but modern psychometric research has demonstrated equal, if not superior, prognostic characteristics and less measurement error among PROs than laboratory-based alternatives. As with any SEB, PROs are not perfect, but they do not have to be perfect; they need to be useful and practical for improving cancer care. The evidence of this and other recent work is mounting that the day that PRO assessments will be integrated into routine practice and other clinical and basic research as just another vital sign may be within sight.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Public Health Service grants CA-25224, CA-37404, CA-35431, CA-35415, CA-35103, and CA-35269.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, et al. Cancer statistics. 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;57:43–66. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang P, Allen MS, Aubry MC. Clinical features of 5,628 primary lung cancer patients: experience at Mayo Clinic from 1997 to 2003. Chest. 2005;128:452–462. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.1.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Cancer Institute. SEER Cancer Statistics Review. 1975–2006. Washington: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchanan D, Milroy R, Baker L, et al. Perceptions of anxiety in lung cancer patients and their support network. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:29–36. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0626-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinberg T, Roseman M, Kasymjanova G, et al. Prevalence of emotional distress in newly diagnosed lung cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:1493–1498. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0614-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen MS, Darling GE, Pechet TT, et al. Morbidity and mortality of major pulmonary resections in patients with early-stage lung cancer: initial results of the randomized, prospective ACOSOG Z0030 trial. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:1013–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.06.066. discussion 1019–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kenny PM, King MT, Viney RC, et al. Quality of life and survival in the 2 years after surgery for non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:233–241. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.7230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bezjak A, Lee CW, Ding K, et al. Quality-of-life outcomes for adjuvant chemotherapy in early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomized trial, JBR.10. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5052–5059. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.6094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan TD, Black D, Bannon PG, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and nonrandomized trials on safety and efficacy of video-assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2553–2562. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cella D, Patel J. Improving health-related quality of life in non-small-cell lung cancer with current treatment options. Clin Lung Cancer. 2008;9:206–212. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2008.n.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson E, Sola I, Subirana M. Non-invasive interventions for improving well-being and quality of life in patients with lung cancer—a systematic review of the evidence. Lung Cancer. 2005;50:163–176. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sloan JA, Dueck A. Issues for statisticians in conducting analyses and translating results for quality of life end points in clinical trials. J Biopharm Stat. 2004;14:73–96. doi: 10.1081/BIP-120028507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sloan JA. Applying QOL assessments: solutions for oncology clinical practice and research, part 1. Curr Probl Cancer. 2005;29(Part 2):271–351. 2006; (30):235–331. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fayers PM, Hopwood P, Harvey A, et al. Quality of life assessment in clinical trials - guidelines and a checklist for protocol writers: the UK Medical Research Council experience. MRC Cancer Trials Office. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:20–28. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(96)00412-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Haes J, Curran D, Young T, et al. Quality of life evaluation in oncological clinical trials – the EORTC model. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:821–825. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bottomley A, Jones D, Claassens L. Patient-reported outcomes: assessment and current perspectives of the guidelines of the Food and Drug Administration and the reflection paper of the European Medicines Agency. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:347–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Efficace F, Bottomley A, Osoba D, et al. Beyond the development of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) measures. A checklist for evaluating HRQOL outcomes in cancer clinical trials—does HRQOL evaluation in prostate cancer research inform clinical decision-making? J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3502–3511. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hahn EA, Cella D, Chassany O, et al. Precision of health-related quality-of-life data compared with other clinical measures. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:1244–1254. doi: 10.4065/82.10.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCorkle R, Young K. Development of a symptom distress scale. Cancer Nurs. 1978;1:373–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Groenvold M, Petersen MA, Aaronson NK, et al. The development of the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL: a shortened questionnaire for cancer patients in palliative care. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruner DW. Outcomes research in cancer symptom management trials: the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) conceptual model. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2007;37:12–15. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgm004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siddiqui F, Kachnic LA, Movsas B. Quality-of-life outcomes in oncology. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2006;20:165–185. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith DJ, Huntington J. Choosing the “correct” assessment tool. Curr Probl Cancer. 2006;30:272–282. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qi Y, Schild SE, Mandrekar SJ, et al. Pretreatment quality of life is an independent prognostic factor for overall survival in patients with advanced stage non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:1075–1082. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181ae27f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bottomley A, Efficace F, Thomas R, et al. Health-related quality of life in non-small-cell lung cancer: methodologic issues in randomized controlled trials. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2982–2992. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huschka M, Mandrekar SJ, Schaefer PL, et al. A pooled analysis of quality of life measures and adverse events data in North Central Cancer Treatment Group lung cancer clinical trials. Cancer. 2007;109:787–795. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Basch E, Jia X, Heller G, et al. Adverse symptom reporting by patients versus clinicians: relationships with clinical outcomes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basch E. Patient-reported outcomes in drug safety evaluation. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1905–1906. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guyatt GH, Osoba D, Wu A, et al. the Clinical Significance Consensus Meeting Group. Methods to explain the clinical significance of health status measures. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:371–383. doi: 10.4065/77.4.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Revicki DA, Erickson PA, Sloan JA, et al. Interpreting and reporting results based on patient-reported outcomes. Value Health. 2007;10(suppl 2):S116–S124. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sloan JA, Frost MH, Berzon R, et al. The clinical significance of quality of life assessments in oncology: a summary for clinicians. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:988–998. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0085-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sloan J, Symonds T, Vargas-Chanes D, et al. Practical guidelines for assessing the clinical significance of health-related quality of life changes within clinical trials. Drug Inf J. 2003;37:23–31. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:79. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sloan JA. The FDA Guidance for patient-reported outcomes: what does it mean and how will it impact clinical trials? Value Health. 2007;10(suppl 2):S146. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sloan JA, Cella D, Hays RD. Clinical significance of patient-reported questionnaire data: another step toward consensus. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:1217–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sloan JA. Assessing the minimally clinically significant difference: scientific considerations, challenges and solutions. Copd. 2005;2:57–62. doi: 10.1081/copd-200053374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Butt Z, Wagner LI, Beaumont JL, et al. Use of a single-item screening tool to detect clinically significant fatigue, pain, distress, and anorexia in ambulatory cancer practice. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Degner L, Sloan J. Symptom distress in newly diagnosed ambulatory cancer patients and as a predictor of survival in lung cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1995;10:423–431. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(95)00056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gotay CC, Kawamoto CT, Bottomley A, et al. The prognostic significance of patient-reported outcomes in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1355–1363. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.3439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Montezari A. Quality of life data as prognostic indicators of survival in cancer patients: an overview of the literature from 1982 to 2008. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:102. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Movsas B, Moughan J, Sarna L, et al. Quality of life supersedes the classic prognosticators for long-term survival in locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: an analysis of RTOG 9801. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5816–5822. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.7420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Higginson IJ, Carr AJ. Measuring quality of life: using quality of life measures in the clinical setting. BMJ. 2001;322:1297–1300. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7297.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang C-H, Cella D, Masters GA, et al. Real-time clinical application of quality of life assessment in Lung Cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2002;4:104–109. doi: 10.3816/clc.2002.n.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Detmar SB, Muller MJ, Schornagel JH, et al. Health-related quality-of-life assessments and patient-physician communication: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:3027–3034. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.23.3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Velikova G, Booth L, Smith AB, et al. Measuring quality of life in routine oncology practice improves communication and patient wellbeing: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:714–724. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taenzer P, Bultz BD, Carlson LE, et al. Impact of computerized quality of life screening on physician behavior and patient satisfaction in lung cancer outpatients. Psychooncology. 2000;9:203–213. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200005/06)9:3<203::aid-pon453>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Buchanan DR, O’Mara A, Kelaghan JW, et al. Challenges and recommendations for advancing the state-of-the-science of quality-of-life assessment in symptom management trials. Cancer. 2007;110:1621–1628. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bergman B, Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, et al. The EORTC QLQ-LC13: a modular supplement to the EORTC core Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ-C30) for use in lung cancer clinical trials. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A:635–642. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90535-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Butt Z, Webster K, Eisenstein A, et al. Quality of life in lung cancer: the validity and cross-cultural applicability of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Lung Scale. Hematol Oncol Clin North Amer. 2005;19:389–420. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gralla RJ, Edelman MJ, Detterbeck FC, et al. Assessing quality of life following neoadjuvant therapy for early stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): results from a prospective analysis using the Lung Cancer Symptom Scale (LCSS) Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:307–314. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0489-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sloan JA, Berk L, Roscoe J, et al. Integrating patient-reported outcomes into cancer symptom management clinical trials supported by the National Cancer Institute–sponsored clinical trials network. J ClinOncol. 2007;25:5070–5077. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.7670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ware JE, Kosinski M. SF-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: A Manual for Users of Version 1. 2nd ed. Lincoln, RI: Quality- Metric Incorporated; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Locke DE, Decker PA, Sloan JA, et al. Validation of single-item linear analog scale assessment of quality of life in neuro-oncology patients [published online ahead of print August 20, 2007] J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:628–638. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hollen PJ, Gralla RJ. Comparison of instruments for measuring quality of life in patients with lung cancer. Semin Oncol. 1996;23:31–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sloan JA, Zhao CX. Genetics and quality of life. Curr Probl Cancer. 2006;30:255–260. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cleeland CS, Mendoza TR, Wang XS, et al. Assessing symptom distress in cancer patients. The M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory. Cancer. 2000;89:1634–1646. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001001)89:7<1634::aid-cncr29>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hobday TJ, Kugler JW, Mahoney MR, et al. Efficacy and quality-of-life data are related in a phase II trial of oral chemotherapy in previously untreated patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4574–4580. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]