Abstract

Background and Aims

Quit & Win (Q&W) contests (in which smokers pledge to quit smoking for a defined period in exchange for the chance to win a prize) may be well-suited for college smokers. We tested the effectiveness of multiple versus single Q&W contests and that of added counselling versus no counselling in smoking cessation.

Design

A two-by-two, randomized controlled trial with 6-month follow-up.

Setting

Nineteen institutions in Minnesota, Texas, Ohio and Wisconsin.

Participants

College student smokers (N=1,217) were randomized within site to four conditions, single (n = 306) or multiple contests alone (n = 309) and single contest plus counselling (n = 296) or multiple contests with counselling (n = 306).

Intervention

Participants in the standard contest condition (Tx1 and Tx2) were asked to abstain from all tobacco products for a 30-day period; those with confirmed abstinence were eligible for a lottery-based prize. Participants assigned to the multiple contest conditions (Tx3 and Tx4) participated in the 30-day contest and were automatically enrolled into two additional contest periods with an escalating prize structure. Participants randomized into the counselling conditions (Tx2 and Tx4) received up to six telephone-administered Motivation and Problem Solving (MAPS) counselling sessions over the 12-week treatment period.

Measures

The primary outcome was biochemically verified 30-day point prevalence (PP) abstinence rate at 6 months. Secondary outcomes were the same abstinence at end-of-treatment (4 months) and a proxy measure of 6-month verified continuous abstinence rate. Outcomes were based on all participants randomized.

Findings

We found no evidence of an interaction between number of contests and counselling. Abstinence rates for multiple (13.5%) and single (11.7%) contests were not significantly different at 6-month (odds ratio [OR] = 1.18, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.84-1.66). The addition of counselling did not significantly improve 6-month abstinence (13.7% versus 11.6%, OR = 1.21, 95% CI = 0.86-1.70). Multiple contests increased abstinence at 4-months (19.3% versus 10.3%, OR = 2.09, 95% CI = 1.50-2.91) and continuous abstinence at 6-months (7.8% versus 3.8%, OR = 2.14, 95% CI = 1.28-3.56).

Conclusion

Multiple Quit and Win contests may increase smoking abstinence rates in college students more than single contests but it is not clear whether adding counselling to these interventions produces any additional benefit.

Introduction

Helping young adults to quit smoking is a national health priority (1). While smokers lose an average of 10 years of life, individuals who quit smoking by age 30 have essentially the same life-expectancy as non-smokers (2). Although the overall prevalence of smoking in the United States has declined over the past 30 years (~18%) (3), the prevalence among young adults aged 18 to 25 has remained flat and high (~33.5%). This includes a surprisingly high smoking rate (23.8%) among college students (4). In 2011, U.S. colleges and universities enrolled over 21 million students annually (5), or nearly 32% of the U.S. population between the ages of 18 and 25. This suggests that there are over 5 million college smokers and more than 1 in 4 young adult smokers are in college.

Quit & Win contests have become one of the more widely disseminated smoking cessation programs worldwide (6). Smokers who join the contest pledge to quit for a brief period (~30 days) in exchange for the chance to win a prize. The assumption is that the chance to win financial incentives and the community support surrounding the contest will motivate a quit attempt and ideally, sustained abstinence following the quit. Two reviews conclude that Quit & Win contests promote quit attempts in target communities and that contest participants are more likely to remain quit, at least short-term, than non-contestant controls (6, 7). In our review of published Quit & Win reports since 2000, initial abstinence rates during the contest period are as high as 50-70%; however, abstinence rates at later follow-up are substantially lower and typically in the range of 10-30%.

One seemingly straightforward approach to increase longer term abstinence among Quit & Win contest participants is to increase the duration of the contest period. This approach is based upon the documented findings that longer periods of abstinence are followed by lower rates of relapse (8-11). Unfortunately, only a handful of studies have offered contests lasting longer than 4-6 weeks (12-16) and differences in study populations and outcomes preclude meaningful comparison of contest duration and outcomes. An extended Quit & Win contest would provide participants with extrinsic rewards (i.e., financial incentives) to motivate a longer period of sustained abstinence. However, an issue of particular importance with respect to Quit and Win contests is how to motivate continued abstinence once the incentive is withdrawn.

The addition of counselling is one method is to enhance intrinsic motives to encourage maintenance of initial abstinence (17) following withdrawal of the extrinsic incentive. Motivational And Problem Solving (MAPS) (18) counselling, designed to combine the style and techniques of Motivational Interviewing (MI) with action-oriented behavioral strategies, has been demonstrated to be effective in three randomized clinical trials with respect to reducing relapse (19-21). This approach could potentially assist Quit & Win participants in increasing their intrinsic motivation for quitting smoking, and subsequently, improve long term abstinence rates.

We conducted a multi-site, randomized controlled factorial trial enrolling college student cigarette smokers attending multiple two- and four-year colleges in the U.S.. The goal of this study was to determine whether augmenting the traditional 30-day Quit & Win contest with additional incentivized contests and with the addition of counselling would improve smoking cessation abstinence rates. Specifically, three main questions were addressed: (1) is there a difference between single and multiple contests on 30-day point prevalence abstinence at 4 and 6 months and on continuous abstinence rates at 6 months; (2) is there a difference in abstinence rates between counselling and no counselling; and (3) is there an interaction between counselling and the number of contests? Although we did not anticipate and interaction effect, discounting this is necessary in order to test questions (1) and (2) independently.

Methods

Study Design

We designed a two-by-two factorial trial with participants (N = 1,217) randomly assigned to four treatment arms: (Tx1) standard, 30-day, Quit & Win contest (n = 306), (Tx2) standard contest plus MAPS counselling (n = 309), (Tx3) multiple contests (n = 296), and (Tx4) multiple contests plus MAPS counselling (n = 306). The study was approved by the University of Minnesota’s human subjects committee.

Setting

During three academic years, 2010-2013, a total of 19 colleges and universities were enrolled to our study. Sixteen were located in Minnesota and the remaining three were in Ohio, Texas and Wisconsin. Two of the schools were private and the remaining public. Five of the schools had an annual student enrollment of <5,000 students); nine enrolled approximately 5,001–15,000 annually and the remaining five enrolled more than 15,000 annually. Eight schools were 2-year colleges with primarily undergraduates and 11 were research institutions with primarily 4-year undergraduates and graduates (referred to as “4-year schools” hereinafter).

Participants

Participants were adult students enrolled at one of our participating schools who smoked on 10 or more days during the past 30 and smoked at least one cigarette on days smoked. Participants intended to stay in school for the entire academic year; were willing to set a quit date approximately one month from study eligibility assessment; had access to a working telephone; were willing to receive telephone “coaching”; and had access to the internet. Participants who also used other tobacco products in the past 30 days were eligible, but were informed that to win the prize they must abstain from all tobacco products (i.e., cigarettes, smokeless, cigars/pipes, hookah).

Participants were ineligible if they were pregnant, screened positive for pathological gambling, or were currently using any smoking cessation methods including nicotine replacement therapy or other medications or counselling to help them quit smoking.

Recruitment, Screening, and Randomization

We recruited participants at the start (September-October) of one of three academic years (2010, 2011, and 2012). Recruitment methods included emails and promotional postcards direct-mailed to all enrolled students at 19 participating campuses. Interested students were instructed to conduct a short online survey to determine eligibility, electronically sign to indicate informed consent, and complete a baseline questionnaire to document demographic, tobacco-related, and psychosocial variables. The final enrollment step was to provide a urine sample for biochemical analysis to document positive smoking status. This occurred in person at pre-specified times and campus locations.

Participants were randomized, in blocks of size 4, to four treatment conditions with a ratio 1:1:1:1, within each site and each academic year. Assignment to each arm across sites was approximately equal but the total number of participants from each site was not equivalent due to school size variability. Assignment was not blinded to study staff or participants.

Interventions

Standard contest

Participants assigned to the standard contest condition (Tx1 and Tx2) were asked to abstain completely from all tobacco products for the 30-day contest period. All were offered a free, two-week supply of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) patch. Patch dose was determined by patient report of cigarettes smoked per day (CPD) and days smoked as indicated on the baseline survey. Specifically, if a participant smoked on ≥25 days per month and smoked ≥ 10 CPD, they were offered the 21mg patch; smoke ≥25 days but <10 CPD, the 14mg dose was offered and if they reported smoking <25 days per month, they were provided the 7mg patch.

During the last week of the contest participants were sent an email containing a link to the assessment survey and were encouraged to complete the survey, regardless of quit status. Those completing the survey received a retail gift card valued at $25. Participants who completed the end-of-contest survey and reported complete tobacco abstinence during the entire 30-day period were asked to provide a urine sample to confirm abstinence. Those with confirmed abstinence were eligible for the lottery-based contest prize – a trip to the Caribbean worth $3,000 or the equivalent value in retail gift cards. The winner was randomly selected by a computerized program.

Multiple contest conditions

During the first month, participants assigned to the multiple contest conditions (Tx3 and Tx4) participated the same standard 30-day contest as those assigned to the standard contest conditions. Regardless of cessation outcome at the end of the first 30-day contest period, participants allocated to the multiple contest conditions were automatically enrolled into two additional contest periods, scheduled with no break in between contests. An escalating prize structure was used to reinforce maintenance of abstinence while also encouraging new quit attempts among those who were initially unsuccessful. That is, the amount of the prize was contingent on the number of contests the participant was tobacco-free and abstinence was verified. For example, if the participant was tobacco-free for one contest month, the prize was $3,000; for two contests, $4,000 and for all three contests, $5,000. At the end of contests 2 and 3, an email was sent to all enrolled participants, including those assigned to the standard contest conditions, encouraging them to complete an on-line survey. Those completing each survey were offered a gift card of $25 and $35, respectively.

Counselling protocol

Participants randomized into the counselling conditions (Tx2 and Tx4) received up to six telephone-administered Motivation and Problem Solving (MAPS) (18) counselling sessions over the 12-week treatment period. The MAPS approach uses motivationally based techniques to enhance commitment and intrinsic motivation for change while combining cognitive-behavioral techniques to target self-efficacy, coping skills, stress management, and negative affect regulation. In collaboration with their counselors, participants developed a wellness plan that detailed barriers to smoking cessation (e.g., negative affect, withdrawal symptoms, craving, academic challenges, relationship stress) and strategies to address each (18). All counselling sessions were audio-recorded for training and monitoring purposes.

Counselors received approximately 40 hours of face-to-face formal training delivered by a specialist trained in the administration and supervision of MAPS protocol. Initial competence/adherence to the protocol, developed to address the potential challenges to tobacco abstinence faced by college students, was assessed during mock counselling sessions using the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity guidelines (MITI, 3rd edition), adapted to include one additional global scale to score “shifting” between MI and PS (specific to MAPS). Ongoing fidelity monitoring was assessed using the MITI to code 10% of each counselor’s sessions each week throughout the treatment phase of the trial. Corrective feedback was given individually as needed and group-based monthly supervision sessions were conducted to assure ongoing compliance. Counselors proactively contacted participants to schedule the first session approximately ten days prior to their quit date. The remaining five sessions were scheduled at the end of each session, at the discretion of the participant, throughout the 16-week treatment period. Counselors were encouraged to spend at least 20 minutes coaching participants during each call.

Follow-up after intervention

Two months after the conclusion of the 12-week intervention period (i.e., 6 months after randomization), participants were asked to complete a final online survey and offered a retail gift card upon completion ($50). Participants endorsing 30-day abstinence were invited to submit a urine sample to verify abstinence.

Measures

The baseline survey assessed sociodemographic, psychosocial, and tobacco-related characteristics. Tobacco-related variables included cigarettes smoked per day (CPD), “time to first cigarette”, a one-item validated measure of nicotine dependence (22) and an investigator developed item, “I’d try to quit smoking this month even if there was not a Quit and Win Contest”.

Each subsequent follow-up survey (i.e., months 1, 4, and 6) asked participants to self-report tobacco abstinence in the past 7 and 30 days (i.e., number of days smoked and average CPD) and other tobacco use (i.e., smokeless, cigars, cigarillos, pipe or hookah) and use of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT).

To determine active smoking status at baseline, urine samples were tested using a combination of NicCheck® (Mossman Associates, Inc., Milford, MA, USA) and NicAlert (Nymox Pharmaceutical Corporation, Hasbrouck Heights, NJ, USA) test strips. The NicCheck® was used first; if this did not confirm positive smoking status, the NicAlert® strip, a more sensitive measure, was used. This same method was employed at the 1-, 4- and 6-month assessments to verify self-reported abstinence. If a participant reported that he or she had used NRT within the past 7 days, the sample was instead sent to the lab for analysis of concentrations of anatabine/anabasine, which are tobacco alkaloids found in the urine of cigarette smokers and smokeless tobacco users but not found among those using medicinal nicotine (>2ng/ml = tobacco use) (23).

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure was biochemically verified, 30-day point prevalence abstinence rate reported at 6-months post-randomization. Secondary outcomes included verified, 30-day point prevalence abstinence at 4-months post randomization or end-of-treatment (end of both contests and counselling) and verified, ‘continuous’ abstinence at 6-months defined as complete tobacco abstinence since the beginning of the first contest as assessed by verified abstinence at the end of each contest period (i.e., end of months 1, 3, and 4) and again at the 6-month follow-up assessment. All analyses of outcomes were performed on an intent-to-treat basis, with treatment considered to have failed (i.e., failure to achieve tobacco abstinence) in participants who did not respond to the assessments (survey or urine verification).

Sample Size Calculation

The study was designed to detect a significant odds ratio (OR) of 1.63 for multiple contests versus standard contest and the same OR for counselling versus no counselling, based on the verified, 30-day point prevalence abstinence rate at 6-month. Sample size calculation was based on 1,000 times simulations with data generated according to the anticipated cessation rates for individual conditions (11%, 17%, 17%, and 24% for Tx1 to Tx4, respectively) and a closed testing procedure(24) based on a logistic regression with main effects only. Given a 90% power and a family-wise type-I error rate of 0.05, we would need 1,256 participants in total or 314 per group.

Statistical Analysis

The interaction between multiple contests and counselling was tested in a logistic regression with the two main effects and their product in order to determine if the analysis of the main effect of a condition should be conducted in a single analysis for all participants, or separately within the levels of the other condition. Homogeneity/heterogeneity across sites was examined using generalized linear mixed models with random intercept (for heterogeneity in cessation rates) and random slopes for the two interventions (for heterogeneity in treatment effects) by sites. If there was evidence of heterogeneity in treatment effects by sites, mixed models would be necessary. Otherwise, logistic regressions would be the primary analysis method to estimate the treatment effects in terms of OR and 95% confidence interval (CI). Secondary analyses using multiple regressions (referred to as “adjusted analysis”) were performed to adjust for participants’ baseline characteristics potentially confounding the treatment effects.

Sensitivity analysis was performed for missing self-report and biochemical verification results for the primary outcome data under the assumption that the missing status (yes or no) and the tobacco use status (yes or no) were independent or missing at random (MAR) (25).

All data analyses were performed in SAS® (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Participant Characteristics

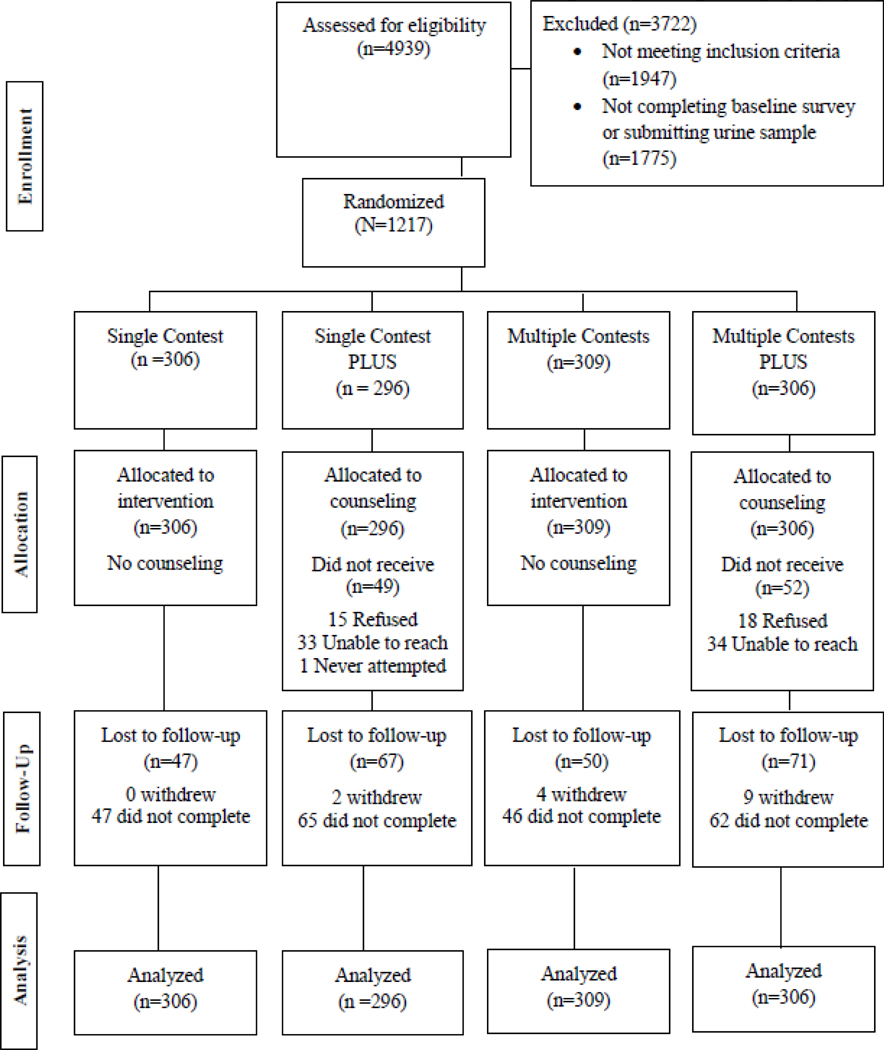

Figure 1 shows the number of participants who were enrolled, and the number who were excluded. Eighty-one percent of those randomized (982/1,217) completed the 6-month follow up assessments. For the 235 (19%) participants lost to follow-up at 6 months, 229 did not complete the final survey and 15 withdrew from the study. For these participants, it was necessary to assume continued smoking or relapse.

Figure 1.

Study Flowchart

Table 1 shows the participant characteristics by treatment condition. Overall, the average age of participants was 26 years, 55% were women, and the majority were white (85.1%). On average, participants were daily smokers who smoked a half a pack of cigarettes per day and nearly half were nicotine dependent. NRT use at months 1, 4, and 6 were 20.1%, 17% and 9%, respectively. There were no adverse events documented for NRT use.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants at baseline.

| Single contest (n = 602) | Multiple contest (n = 615) | No counseling (n = 615) | Counselling (n= 602) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 26.6 (8.0) | 25.9 (7.4) | 26.7 (8.1) | 25.9 (7.3) |

| % Female (n) | 54.7 (329) | 55.1(339) | 56.3 (346) | 53.5 (322) |

| Ethnicity, % (n) | ||||

| White | 85.4 (514) | 84.9 (522) | 85.5 (526) | 84.7 (510) |

| Black | 3.8 (23) | 2.0 (12) | 3.4 (21) | 2.3 (14) |

| Asian | 5.5 (33) | 4.9 (30) | 5.2 (32) | 5.1 (31) |

| Biracial/multiracial | 3.5 (21) | 6.5 (40) | 4.1 (25) | 6.0 (36) |

| Other | 0.2 (1) | 0.5 (3) | 0.5 (3) | 0.2 (1) |

| % Married or cohabiting (n) | 32.6 (196) | 33.9 (208) | 33.2 (204) | 33.2 (200) |

| Type of school, % (n) | ||||

| 2-year | 31.7 (191) | 32.8 (202) | 32.2 (198) | 32.4 (195) |

| 4-year | 68.3 (411) | 67.2 (413) | 67.8 (417) | 67.6 (407) |

| Tobacco smoking | ||||

| CPD on days smoked, mean (SD) | 10.9 (7.3) | 12.1 (8.8) | 11.8 (8.8) | 11.3 (7.4) |

| Nicotine dependent (TTFC ≤ 30 minutes), % (n) | 46.7 (281) | 51.6 (317) | 49.5 (304) | 48.8 (294) |

| a Contemplation ladder, mean (SD) | 7.4 (2.0) | 7.6 (1.9) | 7.6 (1.9) | 7.4 (2.0) |

| Perceived stress scale, mean (SD) | 6.1 (2.9) | 5.7 (2.8) | 5.8 (2.9) | 6.0 (2.8) |

| bI’d try to quit even if there was not a Quit and Win, mean (SD) | 3.1 (1.3) | 3.1 (1.3) | 3.1 (1.3) | 3.1 (1.3) |

Contemplation ladder, ranged 0 (not ready to quit) to 10 (has quit smoking);

range 1-5 for strongly disagree to strongly agree.

SD = standard deviation; CPD = cigarettes per day; TTFC = time to first cigarette after wake up.

Missing Data

The sensitivity analysis of missing data showed consistent effect sizes for the two interventions with the primary analysis in which missing was assumed to be failure to achieve abstinence. Under the MAR assumption, the 30-day point prevalence abstinence rate at 6-month was 22.0% and 25.1% for single and multiple contest groups, respectively (OR=1.18, 95% CI=0.89-1.56) and was 21.2% and 26.0% for no counselling and counselling groups, respectively (OR=1.31, 95% CI=0.96-1.78).

Primary Outcome: 30-day point prevalence verified abstinence at 6 months

There was no evidence of an interaction between number of contests and counselling (χ2(1)=3.24, P=0.072) or heterogeneity in cessation rate or treatment effects across sites (χ2(3)=0.06, P=0.996). There was no evidence of an effectiveness of multiple contests versus contest group or counselling versus no counselling on the primary outcome (Table 2). Effect sizes were similar in logistic regression models that adjusted for all the baseline characteristics shown in Table 1. Specifically, for multiple versus single contest group, OR=1.10 (95% CI=0.74-1.63); and for counselling versus no counselling, OR=1.40 (0.95-2.06).

Table 2.

Smoking cessation outcome.

| Outcome measure | Single contest (n = 602) | Multiple contest (n = 615) | No counselling (n = 615) | Counselling (n= 602) | OR Multiple versus Single contest (95% CI) | OR Counselling versus No counselling (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | ||||||

| Biochemically verified, 30-day PP abstinence rate at 6-month % (n) | 11.7 (70) | 13.5 (83) | 11.6 (71) | 13.7 (82) | 1.18 (0.84 - 1.66) | 1.21 (0.86 - 1.70) |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

| Biochemically verified, 30-day PP abstinence rate at 4-month (end of treatment) % (n) | 10.3 (62) | 19.3 (119) | 14.5 (89) | 15.3 (92) | 2.09 (1.50 - 2.91) | 1.07 (0.78 - 1.46) |

| Biochemically verified, continuous abstinence rate at 6-months % (n) | 3.8 (23) | 7.8 (48) | 5.7 (35) | 6.0 (36) | 2.14 (1.28 - 3.56) | 1.05 (0.65 - 1.70) |

OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; PP = point prevalence.

Secondary Outcome: 30-day point prevalence verified abstinence at 4 months (end-of-Treatment)

There was no evidence of an interaction between two interventions (χ2(1)=0.20, P=0.654). Although there was no evidence of differential treatment effects (heterogeneity in treatment effects) across sites (χ2(2)< 0.01, P > 0.999), there was evidence that cessation rates differed across sites (χ2(1)=5.24, P=0.022). Table 2 shows a benefit of multiple contests on cessation compared with single contest (19.3% versus 10.3%, OR=2.09, 95% CI=1.50-2.91), while there was no evidence of an effect of counselling. Similar evidence was found in the adjusted analysis.

Secondary Outcome: 6-month continuous verified abstinence

No evidence of an interaction between two interventions (χ2(1)=1.78, P=0.182) or any heterogeneity across sites (χ2(3)=1.12, P=0.772). Table 2 shows a benefit of multiple contests on cessation compared with single contest (7.8% versus 3.8%, OR=2.14, 95% CI=1.28-3.56), whereas there was no evidence of an effect of counselling. Similar evidence was found in the adjusted analysis.

Discussion

We did not find evidence of an effectiveness difference between single and multiple contests or between counseling and no counseling at our primary outcome assessment. Further, we did not find evidence of a difference between counseling and no counseling at end-of-treatment or in continuous abstinence rates. However, participants randomized to receive additional contests (both with and without counselling) were significantly more likely to have a verified quit at end of treatment (19.3%) compared with participants who received a single contest (10.3%). Further, continuous abstinence rates were significantly higher in the multiple contest condition at 6 months (15.3% versus 11.1%). These results are promising, especially given that approximately half of college students try quitting without assistance (26) and smokers who attempt to quit smoking without any cessation assistance average only 5% abstinence rates at 6 months (27). This compares to 29.7% using varenicline (28), 20.2% using buproprion SR (28), 22% using the Nicotine Patch (29) and 20.4% utilizing counselling services (30).

Contrary to the expectation that those receiving counselling would have higher abstinence rates than those not receiving counselling, there was no evidence of an effectiveness difference between counseling and no counseling in our sample of college smokers. These results are consistent with prior studies (30, 31). One plausible reason that an effect of counselling was not seen may be due to the fact that although participants randomized to the counselling arms were able to receive up to 6 counselling sessions over the course of 4 months, the overall mean of completed sessions was 2.8, with only 20% of participants completing all 6 sessions. Harris and colleagues (30) examined the efficacy of Motivational Interviewing counselling sessions for smoking cessation in college students and also found no significant differences for 30 day or 6-month follow-up cessation rates between treatment and comparison groups; however they found that a predictor of cessation at follow-up included greater number of sessions attended.

Limitations

A number of limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. First, recent studies demonstrate a high rate of non-daily smoking among college students, with one study finding that 70% of college students were non-daily smokers (32) and another reporting the percent of non-daily smokers at 66% (26). Given the prevalence of non-daily smoking among this population, it is surprising that our sample contained only 21.9% (n=267) non-daily smokers. Thus, participants in our sample may be a self-selected group who are motivated to quit smoking. Because non-daily smokers are less likely to identify themselves as smokers (33), we may have missed a sizeable number of students who are non-daily smokers. Future Quit and Win interventions should encourage non-daily smokers to join and may consider developing recruitment methods to target this population of at-risk smokers. Second, because participants randomized to the multiple contest arms had significantly higher urine submission rates at 4 months, the results should be interpreted with caution. Third, participants in all study groups had a chance to win a lottery prize worth $3,000 and those in the multiple contest arms had additional chances to win a lottery-based prize of up to $4,000 and $5,000. This high level of potential prizes poses a barrier to wide-spread dissemination, as colleges and universities may not have the resources for this level of incentives. Further, students may have assumed their chance to win “a lottery prize” was unlikely and therefore, the improbability may have undermined the ability of the financial incentive to motivate abstinence.

In conclusion, a potential benefit of Quit and Win contests among college students is our observation of an improvement in 4-month abstinence rates when compared to those in the single contest condition. Although this effect washed out at 6-months, a period of abstinence of this duration may increase self-efficacy for abstinence which may contribute to later quit attempts. These results support the effectiveness of lottery- based incentives for ongoing cessation. Acceptability and feasibility were supported by the fact that we were able to recruit and retain a large number of college students in our trial utilizing relatively inexpensive lottery-based (chance to win) incentives. Future studies might examine how lower levels of incentives, more frequent drawings of prizes and guaranteed, performance-based incentives might impact enrollment and abstinence rates.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (5R01-HL094183-04S1, Thomas, PI).

Footnotes

Declarations of Interest: None

References

- 1.Orleans CT. Helping young adult smokers quit: The time is now. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(8):1353. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. Br Med J. 2004;328(7455):1519. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agaken IT, King BA, Dube SR. Prevention CfDCa Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2005–2012 [2014 Contract No.: 63(02)] Morb Mort Wkly Rep. 2012;63: Q7:29–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2012. (SMA) 12-4713. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snyder TD, Dillow SA. Digest of Education Statistics 2012 [National Center for Education Statistcs (NCES) 2014-015] Q8. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, US Department of Education; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hey K, Perera R. Quit and Win contests for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004986.pub2. CD004986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Connor R, Fix B, Celestino P, Carlin-Menter S, Hyland A, Cummings KM. Financial incentives to promote smoking cessation: evidence from 11 quit and win contests. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2006;12(1):44–51. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200601000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cummings KM, Giovino G, Jaen CR, Emrich LJ. Reports of smoking withdrawal symptoms over a 21 day period of abstinence. Addict Behav. 1985;10(4):373–81. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(85)90034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilpin EA, Pierce JP, Farkas AJ. Duration of smoking abstinence and success in quitting. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89(8):572–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.8.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McClernon FJ, Hiott FB, Liu J, Salley AN, Behm FM, Rose JE. Selectively reduced responses to smoking cues in amygdala following extinction-based smoking cessation: results of a preliminary functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Addict Biol. 2007;12(3-4):503–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2007.00075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pierce JP, Gilpin EA. A minimum 6-month prolonged abstinence should be required for evaluating smoking cessation trials. Nic Tob Res. 2003;5(2):151–3. doi: 10.1080/0955300031000083427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chapman S, Smith W, Mowbray G, Hugo C, Egger G. Quit and win smoking cessation contests: how should effectiveness be evaluated? Prev Med. 1993;22(3):423–32. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1993.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elder JP, Campbell NR, Mielchen SD, Hovell MF, Litrownik AJ. Implementation and evaluation of a community-sponsored smoking cessation contest. Am J Health Promot. 1991;5(3):200–7. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-5.3.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elder JP, McGraw SA, Rodrigues A, Lasater TM, Ferreira A, Kendall L, et al. Evaluation of two community-wide smoking cessation contests. Prev Med. 1987;16(2):221–34. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(87)90086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johansson PM, Tillgren PE, Guldbrandsson KA, Lindholm LA. A model for cost-effectiveness analyses of smoking cessation interventions applied to a Quit-and-Win contest for mothers of small children. Scand J Public Health. 2005;33(5):343–52. doi: 10.1080/14034940510005789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rooney BL, Silha P, Gloyd J, Kreutz R. Quit and Win smoking cessation contest for Wisconsin college students. WMJ. 2005;104(4):45–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Markland D, Ryan RM, Tobin VJ, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing and self-determination theory. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2005;24(6):811–31. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vidrine JI, Reitzel LR, Figueroa PY, Velasquez MM, Mazas CA, Cinciripini PM, et al. Motivation and Problem Solving (MAPS): Motivationally Based Skills Training for Treating Substance Use. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2013;20(4):501–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McClure JB, Westbrook E, Curry SJ, Wetter DW. Proactive, motivationally enhanced smoking cessation counseling among women with elevated cervical cancer risk. Nic Tob Res. 2005;7(6):881–9. doi: 10.1080/14622200500266080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reitzel LR, Vidrine JI, Businelle MS, Kendzor DE, Costello TJ, Li Y, et al. Preventing postpartum smoking relapse among diverse low-income women: a randomized clinical trial. Nic Tob Res. 2010;12(4):326–35. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wetter DW, Mazas C, Daza P, Nguyen L, Fouladi RT, Li Y, et al. Reaching and treating Spanish-speaking smokers through the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Information Service. A randomized controlled trial Cancer. 2007;109(2 Suppl):406–13. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Bolt DM, Smith SS, Kim SY, et al. Time to first cigarette in the morning as an index of ability to quit smoking: implications for nicotine dependence. Nic Tob Res. 2007;9(Suppl 4):S555–70. doi: 10.1080/14622200701673480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moyer TP, Charlson JR, Enger RJ, Dale LC, Ebbert JO, Schroeder DR, et al. Simultaneous analysis of nicotine, nicotine metabolites, and tobacco alkaloids in serum or urine by tandem mass spectrometry, with clinically relevant metabolic profiles. Clin Chem. 2002;48(9):1460–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marcus R, Peritz E, Gabriel KR. On closed testing procedures with special reference to ordered analysis of variance. Biometrika. 1976;63:655–60. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Little R, Rubin D. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. New York, NY: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berg CJ, Sutfin EL, Mendel J, Ahluwalia JS. Use of and interest in smoking cessation strategies among daily and nondaily college student smokers. J Am Coll Health. 2012;60(3):194–202. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2011.586388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction. 2004;99(1):29–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jorenby DE, Hays JT, Rigotti NA, Azoulay S, Watsky EJ, Williams KE, et al. Efficacy of varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs placebo or sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2006;296(1):56–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fiore MC, Smith SS, Jorenby DE, Baker TB. The effectiveness of the nicotine patch for smoking cessation: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 1994;271(24):1940–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris KJ, Catley D, Good GE, Cronk NJ, Harrar S, Williams KB. Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation in college students: A group randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. 2010;51(5):387–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lundahl BW, Kunz C, Brownell C, Tollefson D, Burke BL. A Meta-Analysis of Motivational Interviewing: Twenty-Five Years of Empirical Studies. Research on Social Work Practice. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sutfin EL, McCoy TP, Berg CJ, Champion H, Helme DW, O’Brien MC, et al. Tobacco use by college students: a comparison of daily and nondaily smokers. Am J Health Behav. 2012;36(2):218–29. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.36.2.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berg CJ, Lust KA, Sanem JR, Kirch MA, Rudie M, Ehlinger E, et al. Smoker Self-Identification Versus Recent Smoking Among College Students. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(4):333–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]