Abstract

Patient Navigators are trained, lay health care workers who guide patients in overcoming barriers to health care access and utilization. Little evidence exists regarding reach and impact of Patient Navigators for chronic disease management. This study evaluated a Patient Navigator program aimed at optimizing health care utilization among ethnically diverse patients with diabetes and/or hypertension at a community health center (CHC).

Trained Patient Navigators contacted eligible patients who had not seen a primary care provider (PCP) for ≥ 6 months. Outcomes included number of patients reached by Patient Navigators and seen by PCPs after Patient Navigator contact. Distributions and frequencies of outcomes pre- and post-call were compared.

A total of 215 patients had ≥ 1 call attempt from Patient Navigators. Of these, 74 were additionally contacted via mailed letters or at the time of a CHC visit. Among the 45 patients reached, 77.8% scheduled an appointment through the Patient Navigator. These patients had higher rates of PCP visits 6 months post-call (90%) than those not reached (42.2%) (p < 0.0001).

Findings emphasize the value of direct telephone contact in patient health care re-engagement and may inform the development of future Patient Navigator programs to improve reach and effectiveness.

Keywords: Community health center, Patient navigator, Program evaluation, Patient engagement

Highlights

-

•

Patient Navigators (PNs) conducted outreach to community health center patients.

-

•

Patients reached by PNs had higher primary care visit rates than those unreached.

-

•

Findings emphasize the value of direct phone contact in patient engagement.

Introduction

Patient navigation is a process by which an individual, a Patient Navigator, guides patients in overcoming barriers to health care services access to facilitate timely access to care (Paskett et al., 2011, Jean-Pierre et al., 2011, Pratt-Chapman and Willis, 2013, Freeman, 2001, Freeman, 2004). Patient navigation is often conceptualized to promote patient engagement as a key component of improving disease management and health (Barry and Edgman-Levitan, 2012, Foundation, 2014). Patient Navigators can be trained lay individuals or health care professionals (e.g., nurses, health educators, social workers). Types of assistance and scope of service provided by Patient Navigators vary widely depending on Navigators' backgrounds, the care model, and program objectives. Common responsibilities of Patient Navigators include contacting patients to arrange health care visits and transportation, reminding patients of appointments, and assistance with insurance and associated costs (Paskett et al., 2011, Jean-Pierre et al., 2011). Utilization of Patient Navigators is becoming increasingly recognized as an evidence-based approach to address health disparities (Natale-Pereira et al., 2011).

Racial/ethnic minority and socio-economically disadvantaged populations are at disproportionately increased risk for numerous health conditions (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). Factors exacerbating these disparities include poor adherence to medical care (e.g., poor follow up care, high rates of appointment cancelations, high no-show rates, and poor treatment adherence), particularly among patients with uncontrolled conditions such as elevated glucose levels or hypertension (Kaplan et al., 2004, Barron, 1980, Sharp and Hamilton, 2001, Shenolikar et al., 2006, Mojtabai and Olfson, 2003, Safran et al., 2002). A notable strength of Patient Navigators in reducing health disparities is the facilitation of patient outreach, connection, and communication, as Patient Navigators often share similar characteristics with patients, including but not limited to community of residence, culture, language, race/ethnicity, and/or socioeconomic status (Natale-Pereira et al., 2011). These shared characteristics can help establish trust between Patient Navigators and the populations they serve, which can uniquely position them to address and overcome the aforementioned barriers.

The majority of research testing Patient Navigator programs implemented by lay community health workers have targeted cancer screenings and treatment. Studies show evidence of effectiveness of in-person and telephone-based patient navigation in improving access to cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment in racial/ethnic minority populations (Paskett et al., 2011, Jandorf et al., 2005, Leone et al., 2013, Glick et al., 2012, Naylor et al., 2012), and a recent review indicated that patient navigation may also be cost-effective for serving low-income patients (Donaldson et al., 2012). While evidence of their efficacy is strongest in the area of cancer screening and follow-up (Robinson-White et al., 2010, Phillips et al., 2011, Paskett et al., 2006), the role of Patient Navigators is expanding to target other chronic disease and health outcomes (Carrasquillo et al., 2014). However, the reach and impact of Patient Navigators in chronic disease management are not well understood.

Given limited resources of community health centers (CHC), persistent health disparities, and high health care costs, evaluation of Patient Navigator programs is critical to inform practice and practice and optimize resource utilization. This study aimed to evaluate the reach and impact of a CHC-based Patient Navigation program on patient engagement outcomes, including frequency and type of medical visits attended, among patients with type 2 diabetes and/or hypertension who had not been seen by a primary care provider in the previous six months.

Methods

Study site and patient population

The study site was a CHC offering comprehensive services (primary care, medical specialties, dental, behavioral health and social services) to over 25,000 patients in Massachusetts. The ethnically diverse patient population is predominantly of immigrant and/or refugee backgrounds (38% from Central or South American countries, 16% from Puerto Rico, 6% from African countries, and 10% from other countries), representing 94 different languages spoken (Spanish (34%), Portuguese (26%), and English (26%) as the most common languages of preference). Most patients are low-income (77% at or below the federal poverty level), and 35% are uninsured.

Patient navigation program description

Initiated in 2009, the Patient Navigation program aimed to re-engage patients with type 2 diabetes and/or hypertension who had not been seen by a primary care provider (PCP) in the previous six months. Patient Navigators were three women, ages ranging between 25 and 44, who were members of the community serviced by the CHC. Two of them were bilingual (English/Spanish). Patient Navigators were trained by a health care team consisting of registered nurses certified in diabetes education, behavioral health clinicians, and managed care staff. Navigators also completed an established community health worker training program that covered chronic illness education, motivational interviewing skills, health insurance, and appointment scheduling. Patient Navigator responsibilities included contacting patients by phone, building rapport, delivering patient-centered education about the importance of follow up care, scheduling an appointment with their PCP or chronic disease nurse (CDN), assessing need for specialist referrals, identifying challenges to health care access, and providing assistance to overcoming these challenges.

Patient Navigators were instructed to prioritize appointment scheduling with PCPs and CDNs. After patients were connected to the PCP or CDN and attended their visits, Patient Navigators worked with the medical team to schedule other necessary visits and as per plan of care. The protocol for Patient Navigators' contact efforts for unreachable patients included two outreach calls spaced one week apart. If unsuccessful in reaching patients, Patient Navigator mailed outreach letters one week after the second call. If outreach efforts remained unsuccessful at one month, Patient Navigators consulted with patients' PCP regarding next steps, such as an outreach home visit, a mailed certified letter, or no follow up. Patient navigators were salaried CHC employees. The program was funded by a third party payer and funds from this study.

Study eligibility criteria

The study sampling frame included all patients targeted by the Patient Navigator program. Patients were eligible for the program if they had a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and/or hypertension and were “un-engaged” with their medical care, defined as not having seen by a PCP in the previous six months.

Data collection

Patient Navigation program records (2009–2013) were screened by trained research staff to identify all patients with ≥ 1 documented telephone call attempt from Patient Navigators. Data from these patients were then systematically abstracted from electronic health records using an abstraction form developed and pre-tested by our research team prior to its use. Trained research assistants abstracted data of interest from eligible participants' medical records. De-identified data were entered into a dataset and cross-checked and validated independently against medical records by a research coordinator.

Measures

Data abstracted included: type of Patient Navigator contact attempts (i.e., telephone calls, letters, reminders, in-person meetings), outcomes of telephone contact attempts (i.e., directly reached and appointment scheduled, directly reached with no appointment scheduled, unable to reach with a message left, unable to reach with no message left), and frequency and type of medical visits (i.e., primary care visit with PCP and/or CDN, specialty care (e.g., optometry, podiatry, nutritionist, mental health, social services), urgent care, emergency department follow-up visit, or non-routine appointment) in the 12 months prior to and six months following the first Patient Navigator telephone contact attempt. Socio-demographics characteristics included: gender, race, ethnicity, nativity, and need for interpreter services (yes/no).

Statistical analysis

Distributions for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables were computed to describe the study sample. Patients were grouped into four groups by Patient Navigator initial attempted telephone contact results: reached by Patient Navigator (e.g., patient directly answered the phone and spoke with the Patient Navigator) with an appointment scheduled; reached by Patient Navigator with no appointment scheduled; unable to be reached with message left; unable to be reached with no message left. Chi-squared tests were used to make comparisons across these four groups. Medical visits that occurred pre- and post-Patient Navigator initial telephone contact attempt were compared in terms of number and type of visit. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3. All study procedures and protocols were approved by the University of Massachusetts Medical School Institutional Review Board and the Edward M. Kennedy Community Health Center Quality Care Committee.

Results

Two hundred and fifteen patients were targeted by the Patient Navigator and thus were eligible for study inclusion (45.1% male). The mean age of the cohort was 63.4 years (SD = 12.7) and ranged from 20 to 87 years. The majority identified as Latino (57.7%), reported Spanish as their primary language (53.9%), needed a language interpreter (75.4%), and represented numerous countries of nativity. No significant differences in patient socio-demographics by Patient Navigator phone contact outcomes were observed (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographic characteristics for the cohort and by outcome of Patient Navigator (PN) telephone contact attempt among patients (N = 215) in a Massachusetts Community Health Center (2009–2013).

| Overall study sample (N = 215) N (%) |

Reached by PN and appointment scheduled by PN (n = 45) N (%) | Reached by PN and NO appointment scheduled by PN (n = 12) N (%) | Not reached by PN and message left (n = 92) N (%) | Not reached by PN and NO message left (n = 66) N (%) | p-Value⁎ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 97 (45.1%) | 22 (48.9%) | 6 (50.0%) | 39 (42.4%) | 30 (45.4%) | 0.88 |

| Primary language | ||||||

| English | 41 (19.1%) | 11 (24.4%) | 3 (25.0%) | 18 (19.6%) | 9 (13.6%) | 0.66 |

| Spanish | 116 (54.0%) | 24 (53.3%) | 6 (50.0%) | 48 (52.2%) | 38 (57.6%) | |

| Portuguese | 37 (17.1%) | 6 (13.3%) | 2 (16.7%) | 15 (16.3%) | 14 (21.2%) | |

| Other | 21 (9.8%) | 4 (6.8%) | 1 (8.3%) | 11 (12.0%) | 5 (7.6%) | |

| Interpreted needed | 155 (72.1%) | 30 (66.7%) | 5 (41.7%) | 69 (75.8%) | 51 (77.3%) | 0.05 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 124 (57.7%) | 28 (62.2%) | 6 (50.0%) | 51 (55.4%) | 39 (59.1%) | 0.19 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 142 (66.0%) | 24 (53.3%) | 8 (66.7%) | 63 (68.5%) | 47 (71.2%) | 0.05 |

| Black | 65 (30.2%) | 18 (40.0%) | 3 (25.0%) | 26 (28.3%) | 18 (27.3%) | |

| Other | 8 (3.7%) | 3 (6.7%) | 1 (6.7%) | 3 (3.3%) | 1 (1.5%) | |

| Nationality | ||||||

| Puerto Rican | 62 (28.8%) | 15 (33.3%) | 5 (41.7%) | 25 (27.2%) | 17 (25.8%) | 0.30 |

| Brazilian | 38 (17.7%) | 6 (13.3%) | 2 (16.7%) | 15 (16.3%) | 15 (22.7%) | |

| C. American | 22 (10.2%) | 4 (8.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (9.8%) | 9 (13.6%) | |

| Ghanaian | 23 (10.7%) | 4 (8.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 12 (13.0%) | 7 (10.6%) | |

| S. American | 19 (8.8%) | 4 (8.9%) | 1 (8.3%) | 9 (9.8%) | 5 (7.6%) | |

| African | 17 (7.9%) | 5 (11.1%) | 1 (8.3%) | 8 (8.7%) | 3 (4.6%) | |

| Dominican | 14 (6.5%) | 2 (4.4%) | 1 (8.3%) | 6 (6.5%) | 5 (7.6%) | |

| Other | 20 (9.3%) | 5 (11.1%) | 2 (16.7%) | 8 (8.7%) | 5 (7.6%) |

p-Values are from chi-squared tests.

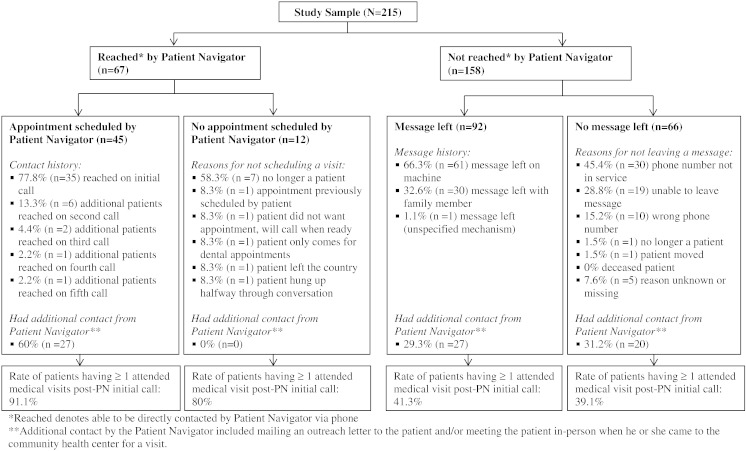

Fig. 1 describes the sample by Patient Navigator contact status and health care utilization (≥ 1) in the 6 months following the first Patient Navigator telephone call attempt. All patients received an initial call attempt from the Patient Navigator, with very few patients (n = 10; 4.6%) having documented additional call attempts (number of additional calls made by the Patient Navigator ranged from 1 to 4 for these patients) (see Fig. 1). Approximately a third (n = 74; 34.4%) of patients received some type of additional contact (outreach letter mailed to patient's residence and/or Patient Navigator met with patient when he or she came to the CHC for a visit) from the Patient Navigator.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of Patient Navigator contact status and appointment show rate attempt among patients (N = 215) in a Massachusetts Community Health Center (2009–2013).

*Reached denotes able to be directly contacted by Patient Navigator via phone.

**Additional contact by the Patient Navigator included mailing an outreach letter to the patient and/or meeting the patient in-person when he or she came to the community health center for a visit.

Of the patients who were reached by the Patient Navigator on the initial call attempt (n = 45), most (77.8%) scheduled an appointment through the Patient Navigator. Of those who were reached but who did not schedule an appointment (n = 12), over half (58.3%) reported that they were no longer patients of the CHC. The majority of the overall sample (n = 158; 75.3%) were not directly reached by the Patient Navigator via telephone. Messages were left via voicemail or with a family member for 58.2% of these participants. Reasons for the Patient Navigator not leaving a message included: disconnected phone number, wrong phone number, patient no longer seen at the CHC, and patient change of residence.

Over half (52.4%) of the study sample had 1 or more visits to the CHC post-Patient Navigator call, excluding those who were identified as no longer patients at the CHC or had changed residence (n = 9). The proportion of patients attending at least one CHC visit in the 6 months following the first initial Patient Navigator call attempt was highest for those reached and who scheduled an appointment at the first call attempt (91.1%), followed by those reached with no appointment scheduled (80%); those unable to be reached with a message left (41.3%); and those unable to be reached with no message left (39.1%) (p < 0.0001).

Table 2 presents distributions of medical visits by outcome of Patient Navigator initial call and medical visit type within the 12 months preceding and the six months following the initial call attempt. Visits were categorized by the following types: PCP visits, CDN visits, specialty visits (e.g., optometry, podiatry, nutritionist, mental health, social services, or other), urgent care, emergency department follow-up, non-routine appointments, and no visits. Due to the small number of patients who had visits with CDNs only, visits with specialist(s), urgent care, emergency department follow-up, and non-routine visits, categories were further broken down as follows: 1) patients who only came to the CHC for PCP visits; 2) patients who had PCP and CDN visits; 3) patients who had specialist(s) visit(s) or other specialist visit type combination (e.g., specialist visit and/or one or more of the following: urgent care visit, emergency department follow-up, or non-routine appointment); and 4) no visits.

Table 2.

Distribution of attended medical visits by type pre and post-Patient Navigator (PN) initial call attempt among Patients (N = 215) in a Massachusetts Community Health Center (2009–2013)a.

| 12 months pre Patient Navigator initial call (N = 215) |

6 months post Patient Navigator initial call (N = 206) (excluding n = 9 who were no longer patients or moved) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reached by PN and appointment scheduled by PN |

Reached by PN and NO appointment scheduled by PN |

Not reached by PN and message left |

Not reached by PN and NO message left |

p-Value |

Reached by PN and appointment scheduled by PN |

Reached by PN and NO appointment scheduled by PN |

Not reached by PN and message left |

Not reached by PN and NO message left |

p- Value |

|

| N = 45 | N = 12 | N = 92 | N = 66 | N = 45 | N = 5 | N = 92 | N = 64 | |||

| PCP visit ONLY | 18 (40.0%) | 5 (41.7%) | 31 (33.7%) | 23 (34.8%) | 0.5921 | 15 (33.3%) | 4 (80.0%) | 19 (20.7%) | 17 (26.6%) | < 0.0001 |

| PCP + CDN visit | 24 (53.3%) | 1 (8.3%) | 33 (35.9%) | 24 (36.4%) | 0.4335 | 24 (53.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 14 (15.2%) | 5 (7.8%) | 0.0082 |

| Specialty visits only or specialty visit combinationb | 3 (6.7%) | 5 (41.7%) | 8 (8.7%) | 2 (3.0%) | 0.0841 | 2 (4.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (5.4%) | 3 (4.7%) | 0.4214 |

| No visits | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (8.3%) | 20 (21.7%) | 17 (25.8%) | 0.0024 | 4 (8.9%) | 1 (20.0%) | 54 (58.7%) | 39 (60.9%) | < 0.0001 |

PCP = primary care provider.

CDN = chronic disease nurse.

p-values are from Χ2 tests.

Specialty visit types included: optometry, podiatry, nutritionist, mental health, social services, or other. Other visit type combinations included any combination of specialty visits and/or visits to the following: urgent care; emergency department follow-up; or non-routine appointment (visits with PCPs or CDNs not included in the specialty visit combination category).

In the 12 months prior to the Patient Navigator initial call attempt, 73.9% of patients came to the CHC for a PCP visit, with 35.8% of patients having visits with their PCP only and 38.1% having visits with their PCP and CDN. Nearly one-fifth (17.7%) of patients did not come in for a visit, and very few patients (8.4%) had specialty visits only or a specialty visit combination (e.g., specialty visit and urgent care visit). Patients who were ultimately unreachable by the Patient Navigator were overrepresented in the category of no visits in the 12 months preceding the initial call attempt (47.5%) compared to reached patients (8.3%) (p = 0.0024).

In the six months following the Patient Navigator initial call attempt, 26.7% of patients had visits with a PCP only, 20.9% had visits with both PCP and the CDN, and 4.9% had visits with a specialist(s). Patients reached by the Patient Navigator and who scheduled an appointment during the call had significantly higher rates of visits with their PCP or their PCP and CDN than patients who were unreachable (p's < 0.05). Few patients had visits with specialist(s) only or specialty combination visit (4–5%) across all groups, and these rates did not differ by Patient Navigator contact status. Patients not reached by the Patient Navigator, regardless of whether or not a message was left, had high rates of not having any medical visit (58–61%) than patients who were reached (9–20%). The majority of patients reached by the Patient Navigator had a visit with their PCP first (64%) before seeing other providers, compared to 27.6% who were not reached (p < 0.0001) (results not shown in tables).

Discussion

Findings from this quantitative evaluation of a Patient Navigator program targeting at-risk patients with type 2 diabetes and/or hypertension provide insight on program reach and effectiveness on an ethnically diverse, multi-lingual, transient patient population. Study findings indicate that, when they are able to reach patients directly, Patient Navigators may be effective in re-engaging patients with diabetes and/or hypertension in receiving primary care. Most patients who scheduled appointments during the Patient Navigator call attended a visit with their PCP or CDN within the following six months, confirming that the program accomplished its purpose of re-engaging reached patients. These results emphasize the value of direct engagement with patients over the phone as a re-engagement strategy, suggesting that direct phone contact with the Patient Navigator may have facilitated a stronger personal connection or enhanced greater self-care motivation from patients than simply receiving a message left via voicemail or with a family member. Patient Navigators are bilingual, bicultural community members; these characteristics are presumed to foster rapport with patients in a manner salient to patients.

This study also showed that the majority of patients were not directly reached by a single call from the Patient Navigator, consistent with previous findings of difficulties reaching CHC patients (Rosal et al., 2010).

This finding emphasizes the importance of multiple call attempts on different days, at varying times, including evenings, to increase reach. However, results showed that less than one-third of patients had more than one documented call attempt, indicating that the majority of patients who were unable to be reached during the initial Patient Navigator call did not receive any type of follow-up attempt. This finding may be explained by the multiple roles and competing demands (e.g., serving as interpreters, providing technical and administrative assistance, arranging health care visits and transportation, reminding patients of appointments, assistance with insurance and associated costs) (Paskett et al., 2011, Jean-Pierre et al., 2011) that Patient Navigators are often faced with. Finally, the high rate of unreachable patients may reflect, at least partially, the highly transient nature of our patient population and their nativity status (foreign-born).

Systems that support Patient Navigators and oversee the implementation of systematic protocols for contacting patients may be critical for maximizing the effectiveness of similar programs. Another strategy for facilitating reach involves expanding Patient Navigator activities to proactively interact with patients at the time of health visits. Establishing this face-to-face connection with patients may increase likelihood of reaching and engaging patients who may ultimately disengage from their care, or perhaps even prevent patient disengagement, but this model has not been tested. Strengths of this study are the inclusion of an ethnically diverse and predominantly non-English-speaking patient population (thus reaching populations often not included in clinical trials) and targeting adults at risk for poor hypertension and type 2 diabetes management, thus contributing to the literature on the role of Patient Navigators in chronic disease management. Findings should be interpreted with caution given study limitations, such as the absence of a comparison group, inadequate follow-up time to determine the association of the Patient Navigator program with health outcomes, and lack of generalizability to other populations. Additional studies examining the type of Patient Navigator activities that are of greatest benefit to patient outreach and engagement are needed.

Conclusion

Guiding and empowering patients to actively process health information and navigate appropriate utilization of the health care system may be essential in improving health care delivery and outcomes and eliminating disparities. Findings from this study may guide future processes and decisions regarding the integration of Patient Navigators within medical teams and population-based medicine guidelines to effectively manage community and population health. Additional studies, including randomized controlled trials, are needed to evaluate efficacy of Patient Navigator programs on patient engagement in chronic disease management.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Patient Navigators for their roles in implementing the program, the Edward M. Kennedy Community Health Center staff for their roles in study recruitment and assisting with data collection and program evaluation, and Margaret Ramos Miller, Jonathan Kassira, Antonia Doherty, Emily Etzel, and David Estabrook for their roles in data abstraction and entry. The Patient Navigator program was funded by Tufts Health Plan and the University of Massachusetts Worcester Prevention Research Center (CDC cooperative agreement number U48 DP001933). This research was funded by the University of Massachusetts Worcester Prevention Research Center (U48 DP001933).

References

- Paskett E.D., Harrop J.P., Wells K.J. Patient navigation: an update on the state of the science. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2011;61:237–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jean-Pierre P., Hendren S., Fiscella K. Understanding the processes of patient navigation to reduce disparities in cancer care: perspectives of trained navigators from the field. J. Cancer Educ. 2011;26:111–120. doi: 10.1007/s13187-010-0122-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt-Chapman M., Willis A. Community cancer center administration and support for navigation services. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2013;29:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman H.P. National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2001. Voices of a Broken System: Real People, Real Problems. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman H.P. A model patient navigation program. Oncol. Issues. 2004;19:44–46. [Google Scholar]

- Barry M.J., Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making—pinnacle of patient-centered care. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:780–781. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foundation C.H. New Era of Patient Engagement. 2014. http://www.chcf.org/publications/2013/02/health-affairs-patient-engagement Available at. (Accessed May 8, 2014)

- Natale-Pereira A., Enard K.R., Nevarez L., Jones L.A. The role of patient navigators in eliminating health disparities. Cancer. 2011;117(15 Suppl.):3543–3552. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Atlanta, GA: 2013. CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report — United States. (November 22 2013/ Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/other/su6203.pdf. Accessed March 13, 2015) [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan R.C., Bhalodkar N.C., Brown E.J., Jr., White J., Brown D.L. Race, ethnicity, and sociocultural characteristics predict noncompliance with lipid-lowering medications. Prev. Med. 2004;39:1249–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron W.M. Failed appointments. Who misses them, why they are missed, and what can be done. Prim. Care. 1980;7:563–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp D.J., Hamilton W. Non-attendance at general practices and outpatient clinics. BMJ. 2001;323:1081–1082. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7321.1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenolikar R.A., Balkrishnan R., Camacho F.T., Whitmire J.T., Anderson R.T. Race and medication adherence in Medicaid enrollees with type-2 diabetes. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2006;98:1071–1077. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R., Olfson M. Medication costs, adherence, and health outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries. Health Aff. 2003;22:220–229. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.4.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safran D.G., Neuman P., Schoen C. Prescription drug coverage and seniors: how well are states closing the gap? Health Aff. 2002:W253–W268. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w2.253. (Suppl. Web Exclusives) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jandorf L., Gutierrez Y., Lopez J., Christie J., Itzkowitz S.H. Use of a patient navigator to increase colorectal cancer screening in an urban neighborhood health clinic. J. Urban Health. 2005;82:216–224. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone L.A., Reuland D.S., Lewis C.L. Reach, usage, and effectiveness of a Medicaid patient navigator intervention to increase colorectal cancer screening, Cape Fear, North Carolina, 2011. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E82. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick S.B., Clarke A.R., Blanchard A., Whitaker A.K. Cervical cancer screening, diagnosis and treatment interventions for racial and ethnic minorities: a systematic review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012;27:1016–1032. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2052-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor K., Ward J., Polite B.N. Interventions to improve care related to colorectal cancer among racial and ethnic minorities: a systematic review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012;27:1033–1046. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2044-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson E.A., Holtgrave D.R., Duffin R.A., Feltner F., Funderburk W., Freeman H.P. Patient navigation for breast and colorectal cancer in 3 community hospital settings: an economic evaluation. Cancer. 2012;118:4851–4859. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson-White S., Conroy B., Slavish K.H., Rosenzweig M. Patient navigation in breast cancer: a systematic review. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33:127–140. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181c40401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips C.E., Rothstein J.D., Beaver K., Sherman B.J., Freund K.M., Battaglia T.A. Patient navigation to increase mammography screening among inner city women. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2011;26:123–129. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1527-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paskett E., Tatum C., Rushing J. Randomized trial of an intervention to improve mammography utilization among a triracial rural population of women. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1226–1237. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasquillo O., Patberg E., Alonzo Y., Li H., Kenya S. Rationale and design of the Miami Healthy Heart Initiative: a randomized controlled study of a community health worker intervention among Latino patients with poorly controlled diabetes. Int. J. Gend. Med. 2014;7:115–126. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S56250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosal M.C., White M.J., Borg A. Translational research at community health centers: challenges and successes in recruiting and retaining low-income Latino patients with type 2 diabetes into a randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36:733–749. doi: 10.1177/0145721710380146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]