Abstract

Background

Children's physical activity (PA) is affected by socio-economic status (SES) and the environment. Children are not fully autonomous in their decision making; parental decisions thus affect how children utilise their surrounding environments for PA. The aim was to examine environmental influences on children's PA from a qualitative perspective in parents from low SES wards in Coventry, UK.

Method

59 parents of children in year 4 (aged 8–9years) completed the ALPHA environmental questionnaire. 16 of these parents took part in focus group discussions examining environmental facilitators and barriers to their child's PA (March–April, 2013).

Results

Emerging themes related to physical (i.e. poor access, safety and quality of the neighbourhood) and social environment (i.e. ‘rough’ neighbourhood due to crime and anti-social behaviour) influences on the PA behaviour of children. The parents believed these environmental factors resulted in the children engaging in greater sedentary activity (watching TV) indoors. The school environment was perceived as a supportive physical environment for children's PA behaviour.

Conclusion

Parent's perceptions of an unsupportive physical and social environment restrict children's opportunities to play outside and be physically active and may lead to increased body fat (BF). Schools provide a supportive environment for children from low SES to be physically active in.

Keywords: Deprived, Youth, Attitude, Neighbourhood, Play, Habitual physical activity

Highlights

-

•

Qualitative study exploring the effect of parental perceptions on child's physical activity.

-

•

Poor perceptions of the physical and social environment limit children's physical activity.

-

•

Parents' safety concerns limit children's physical activity to indoors.

-

•

Religious practice limits time available for physical activity in Muslim children.

Introduction

Children should engage in 60 minutes per day of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) for health benefits (Chief Medical Officer, 2011) but many children fail to meet these guidelines (Eyre et al., 2013a, Eyre et al., 2013b, Owens et al., 2009). Social-ecological models of health behaviour identify the role of environmental influences on physical activity (PA) (Davison and Birch, 2001, Salmon and King, 2005). Several research studies have confirmed that children's PA is affected by the built environment (Griew et al., 2010, Spengler et al., 2011), social environment (Davidson and Lawson, 2006) and socio-economic status (SES) (Duncan et al., 2012, Duncan et al., 2008). Previous research suggests that children living in deprived neighbourhoods have lower PA levels (Griew et al., 2010, Pabayo et al., 2011, Spengler et al., 2011) and suffer from multiple and accumulative experiences of deprivation (e.g. increased traffic volume, pollution, poor housing), which provides less opportunity for PA (Bolte et al., 2010).

Specifically in the UK, people from South Asian (SA) backgrounds are the most socio-economically deprived, clustering in the most deprived areas (Jayaweera et al., 2007, Williams et al., 2009). Some heterogeneity is apparent with Bangladeshi and Pakistani ethnic groups most likely to live in deprived neighbourhoods than Indian ethnic groups (Jivraj and Khan, 2011). Low SES is related to low PA (Duncan et al., 2004). SA children have lower PA patterns than White ethnic groups (Eyre et al., 2013a, Eyre et al., 2013b, Owens et al., 2009) and spend more time indoors inactive (Eyre et al., 2014). Several factors have been found to relate to PA behaviours in adults. External motivators (i.e. weight loss, health, enjoyment and social activity) were the main factors causing SA adults to engage in activity (Jepson et al., 2012). For older SA adults, a recent systematic review of qualitative studies investigating PA in SA, found disempowering and empowering contexts for PA in the following four main themes, communication, relationships, beliefs and the environment, which influenced PA levels (Horne and Tierney, 2012). There is a need to understand factors that affect PA behaviours in ethnic and deprived children in order to design interventions to increase PA levels. However, the approaches used in the majority of prior studies examining the environment have been based on quantitative assessment of PA in particular locations or using GPS technology to map PA patterns (Eyre et al., 2014, McCormack et al., 2004). While this is useful, it is also important to understand the lived experiences of people's interaction with the environment in relation to PA and to understand the impact of SES and environmental experiences on PA (Lake and Townshend, 2012).

Prior qualitative research by Eyre et al. (2013b) in multi-ethnic groups (i.e. South Asian, Black and White) of children (aged 7 to 9 years) from deprived wards of Coventry, found that school, outdoor PA and equipment were facilitative to PA. The study also reported that parental constraints, safety, the home environment and weather were barriers to PA. Furthermore, in a review of qualitative studies, parental support was a facilitator for providing young children with opportunities to be active (Allender et al., 2006). As children identify parental constraints as a barrier to PA and given that they are not fully autonomous in their decision making, it was considered important to understand parental attitudes towards their local environment and how these relate to PA opportunities. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore the attitudes of the parents of the children in Eyre and Duncan (2013a) towards their environment. Secondly, the study sought to identify how these perceptions affect decisions made about the ways in which their children utilise their surrounding area for PA in low SES neighbourhoods. Secondly, the paper sought to understand any ethnic differences in perceptions between White and SA parents.

Method

Participants

Ethics approval was obtained from Coventry University Ethics Committee. Letters with study information were sent to the head teachers from two primary schools in the two most deprived wards of Coventry, UK. Parents were invited to attend a study information session. Participant information sheets were sent to all parents in Year 4 with the Instrument for Assessing Levels of Physical Activity and Fitness (ALPHA) environmental questionnaire. Parents were informed that focus group discussions would be based on their local environment and PA. No incentive was provided for participation. Following informed consent, 59 parents (30–46years) of primary school children (aged 8–9years) completed the ALPHA environment questionnaire at home (Spittaels et al., 2009, Spittaels et al., 2010). 16 parents participated in focus group interviews (Male (Black) = 1, Female = 15, SA = 8, White = 5 and Black = 3). English was an additional language for all SA participants and for one Black participant. Despite this, all participants spoke fluent English.

Instruments for Assessing Levels of Physical Activity and Fitness (ALPHA) environment questionnaire

The ALPHA environment questionnaires (49-item) reliability and validatity against PA measures (self-report/accelerometers: correlations range 0.19–0.38) is reported in adults from Belgium, France, UK and Austria (Spittaels et al., 2010). Further information on the development and use of the scale can be found in Spittaels et al., 2009, Spittaels et al., 2010. The terminology in the questions was reworded to English words in conjunction with school leaders and thus ‘sidewalks’ were changed to ‘footpaths’. Questions 9a–b were removed as they related to the work environment and we were interested in what affected their children's PA, leaving 38 items.

Analysis of ALPHA environmental questionnaire

The data was cleaned and analysed according to the ALPHA environmental questionnaire manual (IPEN, 2012), which can be found at www.thealphaproject.net.

Focus groups

Semi-structured, homogenous (children from the same school) focus group discussions were conducted with parents (4–8 parents per group, consistent with, King and Horrocks, 2010) to generate interactive discussion. All interviews were conducted at the school, were recorded (Olympus VN-750, Tokyo) and facilitated by the first author. Focus groups were continued until the point of saturation (Schensul and LeCompte, 2010) in which no new themes emerged. Focus groups provide a more naturalistic data collection method compared to interview. They allow respondents to build upon responses of other group members, and the free flow of talk provides the opportunity to hear the language and experiences of the respondents over interviews (Wilkinson, 2004). Five main topic areas were used for questioning i.e. knowledge/ beliefs about PA, key sources of knowledge/beliefs about PA, PA patterns, barriers and facilitators to PA. These topic areas have been used in prior research examining barriers and facilitators to PA in Black, White and SA adult and children (Eyre et al., 2013b, Rai and Finch, 1997). Questions were taken from the ALPHA environment questionnaire for the 5th topic. Questions were open ended and probing questions were added where appropriate to gain in-depth responses. The interviews were conducted at school providing a familiar and convenient setting for the parents during school-time.

Analysis of qualitative data

The interviews were transcribed verbatim by the first author and were anonymised (M duration = 45 minutes). Transcripts were analysed using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006). This approach defines thematic analysis as a method in its own right rather than locating the analysis within any of the major analytic traditions (e.g., grounded theory) to enable the lived experience of participants to be better expressed (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Considering thematic analysis as a method in its own right also minimises any effect of potential bias or assumptions made by the researcher within the process of data collection and analysis. A comprehensive overview of this method is provided by Braun and Clarke (2006).

Following familiarisation with all transcripts and initial note making, text relevant to influences on PA behaviour were identified, interpreted and coded. Similar codes were collated to form initial themes and sub themes. Themes, codes and supporting data were reviewed by a second researcher (MD) and interpretations were discussed with authors and refined. The ALPHA environment questionnaire responses were used to triangulate focus groups findings. The guidelines of Lincoln and Guba (1985) were followed to ensure trustworthiness by using audit trail, method and analyst triangulation.

Results

Knowledge and beliefs about PA

The knowledge and beliefs about PA expressed by parents were positive (Table 1). Parents reported that their children want to play and that they want their children to play but safely. Parents believed PA was activity based (movement, play or exercise) and felt their children should be active ‘a few hours a day’. The benefits of PA/exercise were not extensively reported, with parents reporting ‘it's good for you’ or ‘healthy’. The main sources of beliefs were from their husband or media sources (Table 1).

Table 1.

Knowledge and beliefs about PA in Parents from Coventry (March–April, 2013).

| Knowledge and beliefs about PA | |

|---|---|

| Theme | Quote |

|

Activity Active/exercise Play Movement |

‘Being active’ (PG1 & PG2), ‘Doing exercise’ (PG1 & PG3) ‘When the kids are out playing their games, football, skipping’ (PG2), ‘Not just sitting watching the TV and playing on the play stations, something where they can get outside and do something ’ (PG2) ‘Movement over a sustained amount of time’ (PG2) |

|

Benefits of exercise Health good for you Healthy |

‘Yeah but then again you have to think about it that's it's better for you, you know’ (PG1) ‘Being healthy while you're doing the exercise’ (PG1) |

|

Barrier to exercise Tiring |

‘It makes me feel tired depending on what activity you were doing’ (PG1) |

|

Sources of beliefs Family Husband Media source Internet Leaflets |

‘Husband’ (PG1) ‘Internet’ (PG1) ‘Leaflets through the door they have activities coming’ (PG1) |

|

Children's PA level Few hours per day |

‘A few hours a day’ (PG1) |

|

Interest for PA Children want to play and exercise Parents want children to play safely |

‘They want to play, they want you know some exercise’ (PG3) ‘You want to be on your own and the child is playing knowing they are safe ’ (PG3) |

Distance to facilities

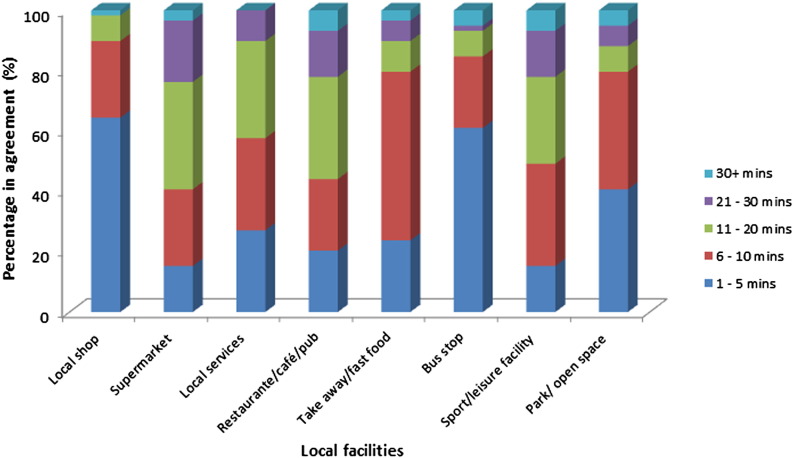

Parents responded that the majority of local facilities (i.e. local shops, bus stops, take away, park/open space, takeaways) were within 10 minutes walking distance (Fig. 1). Sport/leisure facilities, supermarkets and restaurants were up to 20mins away (Fig. 1). From focus group discussions parents agreed that local shops, takeaways, fruit stalls and parks were within the local neighbourhood, but that access to these were restricted by safety (discussed further in neighbourhood safety). They expanded that there were many pubs, but no youth or sports clubs, providing a barrier to their child's PA (Table 2). Parents felt that having more activity centres and youth clubs for families would increase PA (Table 8).

Fig. 1.

Percentage of participants in Coventry in agreement with distance to local facilities (March–April, 2013).

Table 2.

Distance to local facilities (March–April, 2013, Coventry).

| Theme/Quote |

|---|

|

FOOD SHOPS Shops are local (but access hindered by crime) ‘Even the shops are just here from my house and you would have to walk past all that [drugs, drink, dogs and gangs] on the way’ (PG1) Takeaway/fruit stalls ‘We have loads of shops, rammed with takeaways and shops, we do have fruit stalls as well’ (PG1) RECREATIONAL FACILITIES Gym ‘There are some gyms on the Foleshill road but it's more to the bottom. We are pleased with the women's gym as its ladies only and 24 hours, you can use the gym and sauna. You can go whenever you want, when kids are off to bed’ (PG1) Parks ‘there is a park on Stoney Stanton road, I won't take him into that park because I know the state of it…broken bottles and needles. It is just not very well maintained’ (PG2) Pleasant parks outside 1mile radius ‘You have to go right out to like coomb abbey or somewhere its ok there …. But that's really far away Or memorial park that's… But then that's not something you can do every night…. So you just have to make that effort once in a while’ (PG1) Lack of sports clubs in the surrounding neighbourhood ‘There's not enough. I mean, my son was interested in football and there's not one place in Coventry that does football. No, No. Erm the what do you call it, the sports and leisure centre in erm, what do you call it, by pool meadow they don't, they don't do football. Not at weekends, not after school, not nothing. So the only way we found football was at another school which is walking distance but you know it's a trek and you have to pay for it’ (PG3) Lack of youth clubs ‘They need somewhere safe to go. There is nowhere for them to go…If you go from the top of Foleshill road right through into town and you show me somewhere where there is a community centre for kids for them to play’ (PG2) Too many pubs ‘Got too many pubs around here’ (PG3) IMPROVEMENTSLocal youth clubs ‘ If they did like a youth club or something like that , then maybe they can do sessions like karate or self-defence …Yeah so then if anyone does go to grab them then they can handle themselves to get away’ (PG2) |

Table 8.

Mechanisms for getting children to do activities (March–April, 2013, Coventry).

| Best way to get children active | How to encourage parents to be active with children |

|---|---|

|

HOME ENVIRONMENT Activities they can do in the house ‘Indoors in the house ‘ (PG1) Weekends ‘Weekend activities’ (PG1) SCHOOL ENVIRONMENT All activity at school ‘get as much as they can at school’ (PG1) Invest more money into school activities ‘Council are spending it here there and everywhere. Instead of giving it to the schools. If they gave the schools the activity. Yeah so they can give them some more activities’ (PG2) Space ‘All we need is space..... I would be happy to volunteer my time’ (PG1) Public services to visit school for role modelling ‘Then they should have like I just said TA come in, the police come in , you've got the territory army , the cadets , the police , the police service, the ambulance service, why can't they come in and encourage the kids to do something with their lives’ (PG2) LOCAL COMMUNITY Sports centre/youth club ‘So it would be nice if you could drop them off at a centre or something....like a youth club or something. You would know that they are safe and that they are getting looked after; there are no drugs or drink. None of all the bad language of anything like that. …They are safe. Yeah they are supervised’ (PG2) Run by public services ‘If you've got authority there then the TA's, their doing nothing really. They can do a bit of training; they could come and do a youth thing. They stand in town you know what I mean. Do a bit of you thing, children. Get them into the army. Get them to learn respect. Discipline. Do you know what I mean? That is what is wrong with most of them. They haven't got any respect and they haven't got any discipline. They run the street like hooligans....There is not enough youth centres and authority to keep them under control’ (PG2) ENCOURAGEMENT FOR CHILDREN BY: Rewards ‘Children need reward and stuff, something at the end of it’ (PG1) Achievements ‘Achievement if they get something’ (PG1) Working towards a goal ‘Working towards something, something at the end that they can be proud off… I don't think they will do it off their own back it's hard to get them motivated’ (PG1) |

Encourage parents to take responsibility ‘You need to encourage parents to take some responsibility’ (PG1) Get parents involved ‘You need to involve the parents somehow as well as if the child just comes home and says mum I want to do this it's not going to work. The parents need motivation as well. You know we will do this some type of plan’ (PG1) Find out what they do and reach out to the parents that don't do things ‘Some parents probably are motivated and probably do a lot of activities. So some need more so maybe find out from the children themselves what activities they do and the ones that don't do things reach out to their parents’ (PG1) More youth clubs for families: inclusive ‘I don't think we have many youth clubs or centres where families can go together I mean it seems focused on one age group. My son goes but the youngest child that can go is 10 or 11 til 16. ....Youth clubs for younger kids’ (PG1) Activity centres ‘More activity centres that are well managed ’ (PG1) Well maintained ‘Parents could come or even having a coffee room next to the activity place so the parents could actually watch the kids so then they don't have to leave them’ (PG1) Activity pack could do at home (indoor and outdoor) ‘You would try activities in your garden if you were given them. If they came home with a pack then you would do it. ..but If it was an outdoor pack then nobody would want to do it in the winter....It would be nice in the summer but not the winter’ (PG1) Discipline issues in the community ‘We have a few discipline issues. People are brought up to do what they want, they want an easy life and there are no consequences. I see it in adults. Our mum and dads had authority. The population, kids are having kids, they have no authority themselves. The kids are growing up to kids you know what i mean. You have an 18 year old with a 2 or 3 year old kid. Kids are having kids there is no authority there for the kids. SO if they have no authority then they will not give authority where as my mum and dad, they had to work they looked after us and we started. He kids these days are having kids though, they have no authority so what are they going to show their kids. They need authority and respect put into them nothing will come out if you don't put it in’ (PG2) |

Neighbourhood safety

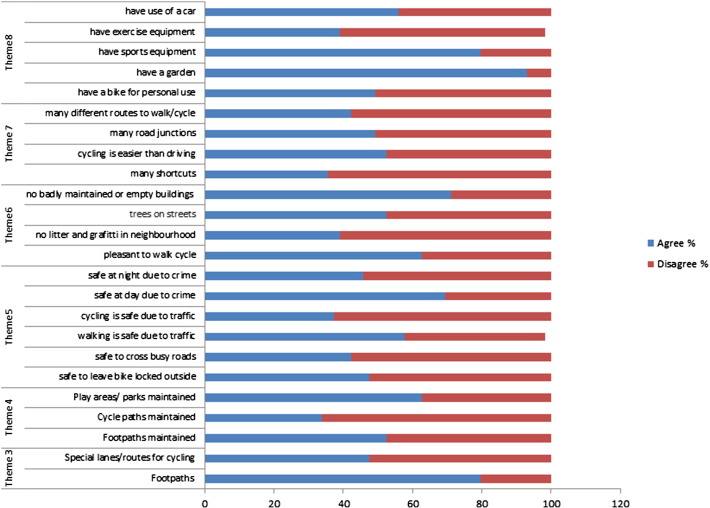

Based on the ALPHA environment questionnaire, parents felt that it was safe in the day (69%, Fig. 2). A substantial part of the focus group interviews centred on neighbourhood safety. It was apparent that parents viewed their local neighbourhood as unsafe because of crime, their social perceptions/fears (heightened by social media), anti-social behaviour on the streets and in local parks, lack of lighting and surveillance in their neighbourhood and breaking traffic rules (e.g. speeding) (Table 3). It was these perceptions which they considered as a main barrier for not allowing their child to play outside ‘You can't leave your children to play on their own its dangerous. I never leave my children in back garden…the area is difficult ’, ‘they are hanging around there with drugs… they throw them into your garden. You can't leave your children outside’ (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

The percentage of parents from Coventry that agree/disagree with the environmental barriers/facilitators (March–April, 2014).

Table 3.

Neighbourhood safety (March–April, 2013, Coventry).

| Crime in local neighbourhood | Social fears/perception towards neighbourhood |

|---|---|

|

Prostitutes ‘Because where I am, there are prostitutes as well in the morning… They're there from morning till evening… It's not as if they make it discrete either is it? they're so obvious, They're so blatant’ (PG3) Trouble/fights ‘Because unfortunately you do get trouble… In my area they don't wait for the dark. They are kicking off all the time, over drugs and stupid things’ (PG1) Attacks ‘And for people getting attacked because an incidence happened at the back of my house err a few weeks ago which was pretty bad’ (PG3) Theft ‘I put that bag out then I was finishing tidying up my rubbish to put in because Friday they supposed to pick., by the time I come back to the bag it wasn't there They took the bag with the clothes in it. Obviously somebody's lifted it. Mugging ‘They become very loud and they pick on kids that are on their own and they mug them and take away whatever they've got off them. …That's happened quite a few times ’ (PG1) Attempted abduction ‘There were warning them… Yeah up by [local school name] up by winginton road, up sandy lane. They were approaching young girls and showing them things on his phone. They had to walk into a shop’ (PG2) |

FEARS Fear for safety ‘I just felt like somebody was watching me. Very scary, very scary. It reminded me to lock the door. In a small time yeah something huge can happen. It just frightened me’ (PG3) Fear that the streets have been taken over ‘they [Teenage youth, gangs, crime] have taken over ’ (PG1) Child abduction fears ‘I am just scared of letting my daughter out to play. You do not know who is about. They could put them in a car; take them off or anything…. So many incidents have happened ….. It is so easy just to pick them up and take them’ (PG2) NEGATIVE PERCEPTION Unsafe streets ‘my streets aren't safe’ (PG1) …‘I won't let my daughter walk to school. We live literally around the corner but I won't let her walk’ (PG2) Rough ‘Very rough [The people], It is very rough. It is not your kid it's the people around. A lot of crime’ (PG1) Not as safe as it used to be when parents were young ‘When we were younger my dad use to go and collect us from the park at 8 saying come home you need to have your dinner. I use to go by myself, my brothers would go by themselves but now you would trust your own child to go alone to the park. It is not safe. What it is with our time when we were 10–20 or 30 odds years we could go by ourselves to the shops to the parks and we could stay out late at night but now I wouldn't let my daughter out of the house, even my 15 year old son’ (PG1) MEDIA CIRCULATION OF INCIDENTS HEIGHTENING FEARS Drug incidents ‘There was one on Facebook the other day he was in bore hill getting the dirty water out of the puddle (all repeat) and injecting himself on the street. So what is that saying? You are not going to let your children anywhere with people like that’ (PG2) Dog incidents ‘Yeah and you've heard a lot of stories about pit bulls and how they have attacked’ (PG1) Child abduction ‘You hear about kids being snatched on the street it is when they are playing so you know it makes you worry’ (PG1) |

| Anti-social behaviour on streets | Anti-social behaviour in parks |

|---|---|

|

Uncontrolled dogs ‘ there is dogs, pit bulls that are just running up and down the streets’ (PG1) Hangout place for gangs ‘And gangs’ (PG1) Gangs and season ‘The gangs they come out earlier on dark nights….. They think it is dark and that they can get up to all sorts because it is darker quickly’ (PG1) Drinking alcohol on streets in groups ‘The cans, they drink in groups, they are just very scary. So you can't take your child there when they are like standing there’ (PG3) Drinking outside local hostel ‘There is a hostel around the corner from my house. There are people; they sit on my wall drinking at night time. I hate it; it really winds me up to be honest. There is not much I can do about it. The police say to give them a ring when it happens and not to approach them but by the time you have done that they have gone’ (PG2) Drug dealing ‘You have drug dealers’ (PG1) Vandalism ‘Vandalism’ (PG1) Racism ‘Your misses got abuse didn’t she’ (PG2) ‘Yeah even she did because they are together. You know what I mean. The abuse she got up by Livingstone road was unreal. All she had done was go to the shop. And its kids that probably weren't at school. Yeah it was school time’ (PG2) Intimidating ‘It can be intimidating. I mean it use to do doors and I will quite openly admit that it can be intimidating these days out and about. It's just one of those things……. It can be intimidating like [person's name] said; the other day I left my house. I was then going around the corner to go to the shop and they were daring each other to give me a dig and give me a quick smack’ (PG2) Throwing things at house ‘you don't know If they are going to throw anything you know we have had things thrown at the window before, or shouting. You have to tell her to stay away from the window’ (PG1) Unsafe garden's You can't leave them. You can't leave your children to play on their own its dangerous. I never leave my children in back garden. …the area is difficult ’ (PG3) ‘they throw it into your garden and they can just knock on our door and check all of back garden because they chuck something….they are hanging around there with drug. You can't leave your children outside’ (PG3) Rough pubs local ‘a pub across the road, they are very rough’ (PG1) |

Uncontrolled dogs ‘There is also something else wrong there. You know dogs, they are so so dangerous. Sometime you don't know… Most of the time, the young lads with their hoods up, with their pit-bulls be walking beside them or whatever not on a lead’ (PG3) Hangout place for teenagers ‘And people just go to sit there at the weekends and as it gets later they collate there. They are not going there to play they are going there to sit but it's like gangs of children. My daughter will say can we go there and it's not even safe to go because I don't feel safe to go. …. Its teenagers….. Yeah teenagers that are mostly bored…… Yeah that has nothing to do …..Yeah they bang on the shops’ (PG1) Drinking alcohol in local parks ‘Especially the Swanswell park because there are groups of people who sit down there in the summer and they drink. Big groups’ (PG3) Drugs taking ‘19/20 year olds smoking whacky backy (weed)’ (PG3) ‘is a park just one park and you can't let your children, there is a drugs’ (PG3) Sexual behaviour ‘They are trying to have rumpy pumpy in the bushes’ (PG2 & PG3) |

| Facilitators of safety | Barriers to safety |

|---|---|

|

SURVEILLANCE Policing ‘Higher police presence’ (PG2) Cameras ‘There should be more cameras’ (PG2), ‘You know they have these alleyways that are supposed to be cut through maybe has some cameras in there and lights’ (PG1) Wardens ‘We need wardens to watch the streets’ (PG1), ‘Put the wardens on the parks and surveillance and things like that’ (PG2) Increased lighting ‘There are some areas where there isn't much lighting as well. There is a road station street west, where the kids go to mosque, there is no light there.... more lightening’ (PG1) ‘There would be less crime with lighting so I would feel safer with lighting’ (PG1) Role modelling from local public services ‘Yeah if police were there then they could teach them while they were there, you know get them into being a firewoman or whatever. Interests The army could come in. You know the TA to help them and keep them off the streets. To make ‘me do something. If they are off the streets then they are not going to be doing drugs or drinking or hanging around with everyone. There isn't going to be pregnancies. If they are shown a bit of respect and authority’ (PG2) Children to learn self-defence (street wise) ‘It is one of those areas where if you are not street wise enough then you could find yourself in positions that you can't handle. Yes like [persons' name] has done boxing, karate etc., he can show the other children the right way to do it. Not the ‘I'm going to punch your head in la de dah’. If it is shown the right way then kids will listen.’ (PG2) |

LACK OF LIGHTING Lack of daylight ‘towards the night… towards 5 or 6 it starts getting darker’ Lack of street lighting at night ‘When you go out at night the streets are too dark. The lights, the street lights are too high up and it's not lighting the pavements up for you to see … It's far too dark…You can't see that far and you don't know what is lurking’ (PG3) LACK OF SURVEILLANCE Lack of warden presence ‘we're supposed to have wardens around here but you don't see them very often’ (PG3) Being alone ‘by myself at night…’ (PG1) |

| Traffic | |

|---|---|

|

RULE BREAKING Speeding ‘Erm traffic, I live on the Foleshill road and the traffic down there I could not let my daughter out , She has road sense, you've got Kashers Lane and Foleshill road and they come up and down there like idiots, so there is no barriers so if they are going to have a car crash then it is coming in your house whether you like it or not (All agree)’ (PG2) ‘Young lads driving their cars thinking they, what makes me laugh is at the top of my road they drive so fast they have to stop when they get to the bottom. We have the speed humps in our road and they're still doing it’ (PG3) Don't stop at crossing ‘Yeah, I say to my daughter don't cross just because there is zebra cross. If you see a car, wait for it to stop before you crossing because some of them yeah they can pass you whilst you are looking…you know they never intended to stop’ (PG3) Driving in wrong lanes ‘it doesn't matter if there's a cycling lane or a bus lane people still drive in them’ Car accidents ‘We've had a few accidents down my road’ (PG3) | |

Additionally, the ALPHA environment questionnaire revealed that traffic made the neighbourhood unsafe to cycle around (63%, Fig. 2). The absence of cycle lanes and the perception that people in their neighbourhood fail to follow the Highway Code were reported in focus group discussion. It was reported “it doesn't matter if there’s a cycling lane or a bus lane people still drive in them’ (Table 3).

Pleasant and aesthetic environment

The ALPHA environment questionnaire highlighted that parents feel that it is pleasant to walk around the neighbourhood (63%, Fig. 2), and that there were not many badly maintained or empty building (71%, Fig. 2). Yet, in the focus group discussions parents felt their neighbourhood was unpleasant and not maintained, sharing complaints about dog mess, rats, rubbish on the streets, graffiti and people urinating on their properties (Table 4). On their walk to school they shared ‘we would find used contraception on the floor… and empty syringes’ (Table 4). Drug needles were also reported along local canal sides. In local parks, parents described how the equipment was broken by older children, drug needles, and broken bottles were present, reporting that this made unsafe/unusable places for children to play. It was described that ‘there is a park… I won't take him into that park because I know the state of it…broken bottles and needles’ (Table 4).

Table 4.

Unpleasant/not well maintained neighbourhood (March–April, 2013, Coventry).

| Theme/quote |

|---|

|

Unpleasant ‘It's not a pleasant area to look at ‘ Not maintained ‘it is not maintained’ (PG3) Graffiti ‘Graffiti as well’ (PG3) Dog mess ‘There is lots of mess, dog muck everywhere...... You walk down there and slip on it or tread in it , it is disgusting’ (PG2) They don't obey the dog fouling signs ‘We do have the dog wardens coming around sticking up signs [about dog mess enforcement rules) but it's not going to work They don't follow it up. There is no cameras or anything’ (PG2) Rats ‘The Foleshill road is wriggled with rats; literally you walk down the Foleshill road. They are not like rats they are like puppy dogs. You come out the bus stop on the Foleshill road at night and a rat will run across your feet’ (PG2) People feeding pigeons ‘I told some people off before because they were feeding them… they just pile chapattis and things on the floor for the ducks …down there. Because they are not just feeding the ducks and the geese they are feeding the pigeons, the rats they are feeding whatever, anyone that sleeps there really’ (PG2) Rubbish on the streets ‘Terrible. See half the time the rubbish around here is just disgusting’ (PG2 & 3) People trailing through bins leaving stuff on the floor ‘You know what's been happening a lot in our street? I don't know if they are Romanians or whatever. Looking in the bins. They take what they want and leave what they took from it. If you find something you like in the bin okay that alright but put everything back how you found it. Now you are leaving me looking like you know like I don't know what I'm doing with all the black bags and rubbish outside. Yeah it's not fair ’ (PG3) Fly tipping ‘But there's people fly tipping as well isn't there? The odd sofa, the odd mattress, the odd yeah’ (PG3) Urinating on property ‘People after they are drunk, they pee next to the door’ (PG3) WALKING TO SCHOOL Used contraception ‘on our route taking our child to school we would find used contraception on the floor’ (PG2) Empty syringes ‘And empty syringes’ (PG2) Canals Drug needles ‘Even if you take a walk down the canal… It's no good. The council says o were cleaning up the canal were doing this, where?? Because there is drug needles. I go fishing and my little girl goes fishing with us and we sit there and I have to leave my fishing rod with my partner and take her home to go to the toilet because she can't do anything around there because there are needles. She can't play around there, she can't do anything. She has to just sit there and fish. You know what I mean. Sometimes they get bored. But they are using drug needles’ (PG2) PARKS Broken equipment ‘The council do not do the parks for the young ones. His kid is only 6 and mine is 8. But he can't take his kid to the park. No not around here. There was but the big ones have broken them’ (PG2) Broken bottles ‘Yeah there is loads of broken bottles’ (PG2) ‘There is a park on Stoney Stanton road. By the doctors. I pass it when I go to the doctors, or go over that way. And he will say can we go in there and I have to say no ‘sorry kid’ not that one. I won't take him into that park because I know that state of it… Broken bottles and needles. It is just not very well maintained’ (PG2) Needles ‘needles as well’ (PG2) STREETS Bins not put back ‘It sounds stupid but obviously being a lollypop lady obviously but every Friday you'll see the dustbin men come …. Now, whether its common sense to me, if I took a bin from number I'd put it back to number four. But no on a Friday when I walk up to my spot basically I have got a bin number four is at number twelve. Number twelve bin is basically at number ninety four. You know it takes me twenty minutes to sort out people's bins. It's not part of my job but if I see a, see a I don't know erm a female with a pram and she has to go in the road because the bins in the way and then apparently I get sacked’ (PG3) ‘Even for children it stops them to come with their own bike to school and they'll give them a prize you know. But Friday you can't come on bike because of that’ (PG3) Maintenance of transport facilities (buses) ‘The buses are like tramps, it stinks, and then you get abuse or something.... it's pretty poor’ (PG2) |

| IMPROVEMENTS |

|

Dog mess bins ‘Dog bins for dog owners.... A glove as well and bags’ (PG1) Clean the streets ‘Erm it needs to be a lot cleaner. I mean, the clean, the streets don't get cleaned very often’ (PG3) |

Cycle and walking networks

Parents were in agreement that that there were many footpaths in the neighbourhood making it is easy to get around (80%, Fig. 2). However, they felt there weren't many shorts cuts or alternative routes for walking (64 %, Fig. 2). From focus group discussions it was clear that in some places there were traffic lights, which made the streets well connected. For other parents, zebra crossings were only present outside of the school. There was feeling that the lack of safe cycle lanes made cyclists ride on the pavement thus affecting walking on pavements. It was felt that more cycle lanes, speeds bumps and education on the Highway Code would improve the walking/cycling network. A parent shared ‘if parks were safe we could actually go ourselves and do some activity’ (Table 5).

Table 5.

Cycle and walking network (March–April, 2014, Coventry).

| FACILITATIVE | BARRIERS |

|---|---|

|

Traffic lights ‘Yes I feel that’s safe, they have traffic lights. The lights they have done are really and because its busy they have done a good job’ (PG1) IMPROVEMENTS Surveillance You need cameras there they should get a fine like they do with traffic lights’ (PG2) Speed bumps ‘Sleeping policemen’ (PG2) Education on UK driving rules ‘A lot of that is education. ..It's a melting pot Coventry.... It is multi-cultural beyond belief. Absolutely, you've got so many cultures all squeezed into so much space, not everyone has sufficient language skills or education. It is a matter of timing really isn't it. It has been easy enough for everybody to get driving licences without enough focus being placed on the education behind it. The green cross code… you know like not knowing about filter lanes’ (PG2) ‘They don't know our roads. If they don't know them they should be made to take a test, they come into the country and they don't know the roads. A driver should be made to take a test for our roads. ....They need the rules, regulations, speeds what they are allowed to do and what they are not allowed to do because they come over here , they get on our roads , then they know one of our children over and they are like well I don't know… they have a licence from Poland or whatever or not insured’ (PG2) More cycle lanes and clear guidance ‘Cycle lanes…So you know it clear guidance with the bikers who want to ride… You see bike, usually on pavements, we are pavement with our foot and dog walker is using pavement. I can ride the bike but I scared to ride here because the pavement… Is very small and sometime small pavement and the bins also two three bins. There no space and bikes’ (PG3) |

Lack of zebra crossings away from school ‘We've only got, we've only got one crossing here and that's because we've got a school…. Apart from that, I don't know of any crossing around here’ (PG3) People fail to follow driving rules Don't stop for lollipop lady ‘Yeah if [lollipop lady's name] is trying to stop them and they're passing her, then they're passing the kids aren't they?’ (PG3) Drive wrong way down one way streets ‘On the one way streets no one ever follows the rules… so it's not safe for the kids’ (PG1) Drive in cycle or bus lanes “It doesn't matter if there is a cycling lane or bus lane, people still drive in them’ (PG2) Cycle paths unsafe ‘love to go cycling but I just take her around the block and back in as I just don't know what to do with her…If the parks where safe then we could actually go ourselves and do some activity, you know walking or an evening stroll We could take our kids with us and do activity but they are not safe ‘ (PG1) Speed on the roads at night ‘It is like a race track along the Foleshill road at night from half 8 or 9 onwards … They come from along the Foleshill road and down cashers lane and then onto Kingfield. It is unreal. It is mad’ (PG2) |

Home environment

Parents agreed that they had access to a garden and small sports equipment (garden = 93%, sports equipment = 80%, Fig. 2). Despite this positive physical environment/equipment, the focus group discussions revealed that parents feared for their children's safety when playing in the garden because of people throwing things into the garden and general anti-social behaviour (Table 6). From focus group discussions parents reported a pattern of sedentary behaviour for children in their home environment, reporting ‘It is the weekend, they are always inside the house. Yeah, there's nothing that goes on in the weekend, they are always inside the house. We don't trust the area… to let your children go out and play’ (Table 6). It was also felt that involving parents in interventions alongside providing a pack with activies that parents and children could try at home, would increase PA in children (Table 8).

Table 6.

Home environment (March–April, 2013, Coventry).

| Home environment | |

|---|---|

|

Weekdays (afterschool) Indoors TV and games Dinner, homework, TV Mosque, homework, bed Weekends Indoors Play with toys TV Outside of home environment (active child) Youth Clubs Sports clubs Recreational facilities Bike rides Garden Anti-social behaviour / safety People jumping into the garden or throwing things over Crime Small gardens House |

‘TV and games’ (PG1 & PG2 & PG3) ‘come home from school, put the dinner on, lock the door at 6, she gets changed into her Pj's and does her homework or whatever she has got to do. She sits there and watches Cbeebies or whatever is on tele’ (PG2) ‘Kids have to go mosque so by the time they have gone to mosque come home, done their homework it is bedtime. ......so no time to do any other activities apart from at the weekends’ (PG1) ‘It is the weekend; they are always inside the house. Yeah, there's nothing that goes on in the weekend. They are always inside the house. We don't trust the area.... To let your children go out and play’ (PG3) ‘Play with their toys’ (PG1) ‘For children , The whole day school and when they come back they just in living room or dining room sitting and watching TV.. No cycling, no exercise and that's why they get’ (PG1, 2 & 3) ‘He goes to youth clubs, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday. They do different activities like table tennis and snooker and he rides his bike there’ (PG1) ‘He plays football’ (PG1) ‘Swimming on Saturdays’ (PG1) ‘Go on bike rides’ (PG1) ‘Mine is a back garden but because I live on the corner we have a back gate but then you get people looking through the gate through the hole and you get people throwing things over the gate, just for the fun of it or whatever’ (PG1) ‘Where I live my garden is quite small I have got my own entrance at the back but it's not safe and that's where mostly the dealing goes on and stuff, so I've got people jumping into my garden and you know throwing stuff and stuff like that. The kids are really scared as well’ (PG1) ‘Behind the garden… there is a passageway where people cut through to go to the shops, so we get all the drunken people at the back of there and one has even jumped over the back of our fence and nicked a motorbike. They got into my husband's garage and they nicked the motorbike but the police couldn't do anything about it’ (PG1) ‘Yeah because you can't really do much because the gardens aren't that big’ (PG2) ‘Your house isn't that big (PG2)… Not enough room to put exercise machines’ (PG3) |

School environment

All parents highlighted the importance of their child's school on their child's PA patterns. Parents reported ‘the school plays an important role in their activity…they mainly [get PA] through school…because they are here most of the time…They have loads in this school and I think this school is brilliant for that…but every other school hasn't got that’ (Table 7). However, parents expressed a view that extra school provision only encompassed the hour after school and, following this there were no other opportunities available within their neighbourhood outside of these hours (Table 7). The school environment was also viewed as a mechanism for getting the children to be more active. Parents felt that children should get as much activity as they can from school, that the council should invest more money into school activities and that public services could visit schools to provide role modelling for careers (Table 8).

Table 7.

School environment (March–April, 2013, Coventry).

| School environment | |

|---|---|

|

Opportunities Main environment for PA Building block for future/continued PA Equipment Playground Gym trainer Adventure playground Omega Camping at school site (safety) Sports clubs at school Range of opportunities |

‘The school plays an important role in their activity, They mainly [get PA] through school ….. because they are here most of the time’ (PG1) ‘My son use to play football at school and he has continued it because the PA was so good here’ (PG1) ‘Yeah because they pick it up from school in year 5 and 6 and then some children continue the sport so it's a good thing’ (PG1) ‘They have loads in this school and I think this school is brilliant for that …. but every other school hasn't got that’ (PG2) ‘Running around the playground, running here and running there… erm they do a lot. In this school they give them quite a lot’ (PG2)‘They have the gym trainer’ (PG1)‘The swings, and climbing frames they have loads in the school’ (PG1) ‘The Mooga’ (PG1) ‘Like ours go camping don't they..... We still have to pay but they camp in their school site. It is all safety. That is the only time I would let my daughter do it. But it is all money, money’ (PG2) ‘My son does at school basketball football everything. .. They do, in the school we have a lot of activities everyday going on in school. Like on a Monday there's a judo class, they do acro, they do street dance they do lots of activities after school. We have lots of, quite a lot of sport activities here; football, netball. My daughter's in football and netball. But That's just 3 to 4oclock. It's for one hour though’ (PG3) |

Parental constraints and gender or age

Parental constraints were driven by their perceptions of an unsafe surrounding environment, which limited how children utilised their surrounding environment for PA. This was not specific for boys or girls, with parents objecting to the view that they were over protective of girls stating ‘I wouldn't let my kids run around my street…I mean they say we are more protective with our daughters but even my son I would not let him out…so it is our sons as well now’. There appeared to be some age differences with primary aged children not allowed out, whereas there was more independent mobility for older teenagers (15 years). It was described that ‘kids are limited because they are younger so they need supervision and can't do things on their own’.

Parents' life constraints

Other barriers related to parents lack of knowledge about clubs (‘I don't know of any clubs, even in summer holidays’) time (‘our kids are missing out because we haven't got the time. We have to go to work; you've got to do other things in the house’), energy (‘Sometimes you're knackered when you get home from school’ ) and money for activities (‘I would love to take my daughter something like that [karate]…But I have £7 left out of my wages, I can't do nothing with that. By the time I have paid my bills and everything else. What can I get my daughter for £7’), especially if parents had more than one child. For parents from Muslim backgrounds Religion was identified as barrier, which limited the time they had to engage in other activities (‘Kids have to go mosque so by the time they have gone to mosque come home…it is bedtime…so no time to do any other activities apart from at the weekends’ (Table 6).

Discussion

This is the first study to consider the lived experience of parents living in deprived environments and how this affects their child's PA. The findings are supportive of the physical and social environmental determinants of outdoor PA and overall PA patterns of children. It was apparent that unsupportive physical and social environmental factors within the neighbourhood caused fear for parents and thus inhibited the children's ability to play outside (Grow and Saelens, 2010), in local parks or in their garden and thus resulted in spending their time indoors watching TV when not at school.

Knowledge and belief about PA

Parent's had limited knowledge about the benefits of PA, with family or media being the main sources of knowledge as similarly reported by Rai and Finch (1997). In previous research, low SES children had a good understanding of the benefits of PA (e.g. physiological, psychological and skill development) and the importance of engaging in PA for current and lifelong health, which was gained from school teachers (Eyre et al., 2013b). Given parents limited knowledge, it seems viable to suggest that this is why SA children fail to report their parents as a source of knowledge. Parental support, parental influences, role modelling and the importance of school for encouraging healthy behaviours and habits has been described in previous research (Finn et al., 2002, Gustafson and Rhoes, 2006, Kamtsios and Digelidis, 2008) but this study is the first to qualitatively explore ethnic parental influences.

Physical and social environmental determinants of PA

Neighbourhood safety

It was apparent that there were parks within 10 minutes walking distance. However, a non-supportive physical and social environment affected the ability to play in these environments due to safety concerns. In previous research the availability and proximity of recreational space or public open spaces was associated with PA (Duncan et al., 2012, Loureiro et al., 2010, Nielsen et al., 2010, Tappe et al., 2013, Veitch et al., 2010). However, this present study suggests that availability alone does not predict behaviour and that despite availability, if parents perceive these parks as unsafe they will not let their children play there.

From focus group discussions, it was further identified that parents constrained children's behaviour of ‘playing out’ in relation to their own safety concerns, consistent with previous research (Veitch et al., 2010). Parents felt their neighbourhood was ‘rough’ due to a range of social and physical factors (e.g. lack of lighting, lack of surveillance, increased crime and anti-social behaviour) which prevented them allowing their children to play in local parks, streets or their own garden. However, these safety concerns were not identified in the questionnaire responses. This mismatch between responses might be due to various reasons such as the cultural interpretation of the questionnaire, the interpretation of a Likert scale and the ability of focus groups to enable discussion and understanding. Thus, it is felt that the responses gained from the focus group discussions may reflect the parents true fears, and supports previous findings that parental constraints and safety concerns are a main barrier to children PA outdoors (Eyre et al., 2013b, Loureiro et al., 2010). These fears may explain the low numbers of children meeting PA guidelines, the low contribution of after-school PA and weekend PA to total MVPA found in the children of the parents used in this study (Eyre et al., 2014).

Aesthetics of the surrounding environment

It was clear that fears of crime related behaviours made the neighbourhood unpleasant for parents. Common complaints were dog fouling, rubbish (causing rats), graffiti, ‘used contraception’, empty drug syringes, broken equipment and bottles in parks, which made environments unsafe/unuseable places for children to play. Rubbish and dog fouling were identified as the top problems in deprived wards of Coventry (Coventry City Council, 2010) and neighbourhood aesthetics have been associated with higher reported PA (Tappe et al., 2013). Given that the parents had a low perception of the neighbourhood aesthetics, this might explain some of the low PA patterns found for children from the same area in Eyre et al. (2014).

Home environment

It was apparent that the social and physical surrounding environment resulted in a low perception of the neighbourhood and fears of child safety if children played outdoors. This resulted in the children on the whole, spending time indoors on weekdays and weekends watching TV and/or playing with their toys. Despite having a garden, parents expressed fears of anti-social behaviour, which restricted their child's activity to indoors. Their home environment meant that there wasn't enough space indoors to do PA, and parents felt it was hard to entertain their children in home environments with limited space, thus resulting in increased media entertainment engagement. These findings support research in lower income households, where greater access to media devices was provided, increased opportunity for sedentary behaviour and less for PA (Tandon et al., 2012). This also provides context to the findings in Eyre et al. (2014) where SA children spent increased time indoors inactive.

School environment

All parents highlighted the importance of the school on their child's PA patterns. It was a place of opportunities (e.g. facilities at the school and sports clubs) and a building block for future PA. Parents felt their children were most active at school, which supports prior research evidencing that half of total MVPA was accumulated at school (Eyre et al., 2014). In previous qualitative studies, children highlighted the importance of the school environment on their PA (Eyre et al., 2013b, Kirby et al., 2013). However, parents shared concerns for availability outside of school, suggesting that after-school clubs are just one hour and that limited opportunities out of school, weekends and school holidays exist. Given the heightened safety concerns resulting in children being restrictive to their home environment and the influence of school on children's PA, these findings highlight the usefulness of providing safer and supervised opportunities through school as a mechanism for maximising PA (Martin et al., 2012).

Religious practice

Parents identified ‘Mosque’ as a barrier to PA in SA children. Attending mosque is a religious practice which is specific to Pakistani (i.e. Muslim) ethnic groups and is viewed as high priority over PA. The parents identified that children spend approximately 2 hours per evening and weekends at mosque, which limits the time available for other activities, especially in the winter. Many school clubs are run immediately after school, which may minimise opportunities for Pakistani children to be involved in the clubs due to conflicting interests with religious practice. These findings are supportive of prior research, which has highlighted the importance of religious practice in SA children and adults (Pallan et al., 2012, Eyre et al., 2013b, Rai and Finch, 1997). For Muslim children in PE, conflicts relating to PE kit, showers, Ramadan and provision of extra curriculum activities have been proposed as barriers to engaging in PA (Carroll and Hollinshead, 2013). These factors were however not identified in this current study, despite this though they identify the need to understand religious practices when designing ethnic minority focused interventions to increase PA.

Autonomy: age and gender

It was apparent that young children are not fully autonomous in their decisions and parental constraints limit the availability to be physically active (Panter et al., 2010). Parents shared how younger children need supervision outdoors with a responsible adult. Contrary to previous findings (Jones et al., 2009b), constraints applied to both boys and girls equally. Yet older children (15 years) were given more independent mobility than younger children (8–9 years) because parents' younger children needed constant parental supervision in the ‘unsafe neighbourhood’.

Improvements

The parents' suggestions for reducing their fears related to changes in the physical environment (e.g. surveillance, increased lighting, speed bumps, cleaning streets) and social (e.g. highway code education), which would make them feel safer and improve the neighbourhood. To increase PA, parents felt maximising opportunities through schools, youth clubs, parental involvement, activities indoors and on weekends would be beneficial.

Limitations

It is likely that fathers will report different perceptions than mothers; yet, the majority of participants in the present study were mothers. In the schools involved in the present study it was only mothers who were responsible for bringing the children to and from school, thus the findings are representative of the mother's role in the community. The research was carried out by a White, English, Female. While this did not appear to influence the data collected, it is possible that this may have had an implicit effect on the data collection process and the responses given by the parents.

Conclusion

The findings of this study support the contextual model by Grow and Saelens (2010) that an unsupportive social and physical environment limits PA opportunities outside. The findings show little ethnic differences but highlight the role of SES and parental perceptions in determining PA behaviour in children. It was apparent that despite having access to local facilities to be active, these environments were perceived as unsafe and unpleasant places to play even with parental supervision. The role of the physical environment at school for providing PA for children was an important facilitator of children's PA. Policies need to focus on building supportive social and physical environments for children to play safely in deprived environments and maximising PA through school.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests.

References

- Allender S., Cowburn G., Foster C. Understanding participation in sport and physical activity among children and adults: a review of qualitative studies. Health Educ. Res. 2006;21:826–835. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolte G., Tamburlini G., Kohlhuber M. Environmental inequalities among children in Europe — evaluation of scientific evidence and policy implications. Eur. J. Public Health. 2010;20:14–20. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckp213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Quali. Res. Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll B., Hollinshead G. Ethnicity and conflict in Physical Education. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2013;19:59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Chief Medical Officer . Department of Health; UK: 2011. UK Physical Activity Guidelines. (Available from) https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-physical-activity-guidelines (2 September 2012) [Google Scholar]

- Coventry City Council . Corporate research team; 2010. Facts about Coventry. (Available from) http://www.facts-about-coventry.com/textonly.php (20 September 2011) [Google Scholar]

- Davidson K.K., Lawson C.T. Do attributes of the physical environment influence children's activity? A review of the literature. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2006;3:19. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-3-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison K.K., Birch L.L. Childhood overweight: a contextual model and recommendations for future research. Obes. Rev. 2001;2:159–171. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2001.00036.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan M.J., Al-Nakeeb Y., Nevill A., Jones M.V. Body image and physical activity in British secondary schools. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2004;10:243–260. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan E.K., Duncan J.S., Schofield G. Pedometer-determined physical activity and active transport in girls. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008;5 doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan M.J., Birch S., Al-Nakeeb Y., Nevill A.M. Ambulatory physical activity levels of white and SA children in the UK. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101:156–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre E.L.J., Duncan M.J. The impact of ethnicity on objectively measured physical activity in children. ISRN Obes. 2013:1–15. doi: 10.1155/2013/757431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre E.L.J., Duncan M.J., Smith E., Matyka K.A. Objectively measured patterns of physical activity in primary school children in Coventry, the influence of ethnicity. Diabet. Med. 2013;30:939–945. doi: 10.1111/dme.12186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre E.L.J., Duncan M.J., Birch S.L., Cox V. Environmental and school influences on physical activity in South Asian children from low socio-economic backgrounds: A qualitative study. J. Child Health Care. 2013;21 doi: 10.1177/1367493513508845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre E.L.J., Duncan M.J., Birch S.L., Cox V. Physical activity patterns of ethnic children from low socio-economic environments within the UK. J. Sports Sci. 2014 doi: 10.1080/02640414.2014.934706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn K., Johannsen N., Specker Factors associated with physical activity in preschool children. J. Pediatr. 2002;140:81–85. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.120693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griew P., Page A., Thomas S., Hulsdon M., Cooper A.R. The school effect on children's school time physical activity; the Peach project. Prev. Med. 2010;51:282–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grow M.G., Saelens B.E. Physical activity and environments which promote active living in Youth (US) In: Lake A.A., Townshend T.G., Alcanides S., editors. Obesogenic Environments. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; West Sussex: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson S.L., Rhoes R.E. Parental correlates of physical activity in children and early adolescents. Sports Med. 2006;36:79–97. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200636010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne M., Tierney S. What are the barriers and facilitators to exercise and physical activity uptake and adherence among South Asian older adults: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Prev. Med. 2012;55:276–284. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IPEN . IPEN; 2012. ALPHA Environmental Questionnaire Manual. (Available from) http://www.ipenproject.org/documents/methods_docs/Surveys/ALPHA_Manual.pdf (10th January 2012) [Google Scholar]

- Jayaweera H., Hockley C.A., Redshaw M.E., Quigley M.A. National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit; 2007. Demographic and socio-economic characteristics of ethnic minority mothers in England: The millennium cohort study. (Available from) Oxford http://www.cls.ioe.ac.uk/library-media%5Cdocuments%5CMCSTechnical%20Paper%20March%2007.pdf (8 September 2012) [Google Scholar]

- Jepson R., Harris F.M., Bowes A., Robertson R., Avan G., Sheikh A. Physical activity in South Asians: An in-depth qualitative study to explore motivations and facilitators. PLoS One. 2012;2012:7(10). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jivraj S., Khan O. Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE); Manchester: 2011. The dynamics of diversity: evidence from the 2011 Census. [Google Scholar]

- Jones A., Hillsdon M., Coombes E. Greenspace access, use and physical activity, understanding the effects of area deprivation. Prev. Med. 2009;49:500–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamtsios S., Digelidis N. Physical activity levels, exercise attitudes, self-perceptions and BMI type of 11 to 12-year-old children. J. Child Health Care. 2008;12:232–240. doi: 10.1177/1367493508092510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King N., Horrocks C. Sage; London: 2010. Interviews in qualitative research. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby J., Levin K.A., Inchley J. Socio-environmental influences on physical activity among young people: a qualitative study. Health Educ. Res. 2013;28:954–969. doi: 10.1093/her/cyt085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake A.A., Townshend T.G. Exploring the built environment, physical activity and related behaviours of young people attending school, college and those not in employment. J. Public Health. 2012;35:57–66. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fds059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y.S., Guba E.G. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1985. Naturalistic enquiry. [Google Scholar]

- Loureiro N., Matos M.G., Santos M.M., Mota J., Diniz J.A. Neighbourhood and physical activities of Portuguese adolescents. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010;5:33. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin K., Bremner A., Salmon J., Rosenberg M., Giles-Corti B. School and individual-level characteristics are associated with children's moderate to vigorous — intensity physical activity during school recess. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health. 2012;36:469–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2012.00914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack G., Giles-Corti B., Lange A., Smith T., Martin K., Pikora T.J. An update of recent evidence of the relationship between objective and self-report measures of the physical environment and physical activity behaviours. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 2004;7:81–92. doi: 10.1016/s1440-2440(04)80282-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen G., Taylor R., Williams S., Mann J. Permanent play facilities in school playgrounds as a determinant of children's activity. J. Phys. Act. Health. 2010;7:490–496. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.4.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens C.G., Nightingale C.M., Rudnicka A.R., Cook D.G., Ekelund U., Whincup P.H. Ethnic and gender differences in physical activity levels among 9–10 year old children of white European, south asian and african caribbean origin. The child heart health study in England (CHASE) Int. J. Epidemiol. 2009;18:1082–1093. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pabayo R., Belsky J., Gauvin L., Curtis S. Do area characteristics predict change in moderate- to-vigorous physical activity from ages 11 to 15 years? Soc. Sci. Med. 2011;72:430. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallan M., Parry J., Adab P. Contextual influences on the development of obesity in children: A Case study of UK South Asian Communities. Prev. Med. 2012;54:205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panter J.R., Jones A.P., van Sluijs E.M., Griffin S.J. Neighbourhood, route, and school environments and children's active commuting. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2010;38:268–278. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai D.K., Finch H. HEA; 1997. Physical activity ‘from our point of view’ Qualitative research among South Asian and Black Communities. (Available from) http://www.nice.org.uk/niceMedia/documents/physical_ourpov.pdf (25th August 2010) [Google Scholar]

- Salmon J., King A.C. Population approaches to increasing physical activity among children and adults. In: Crawford D., Jeffrey R., editors. Obesity Prevention in the 21st Century: Public Health Approaches to Tackle the Obesity Pandemic. University Press; Oxford: 2005. pp. 129–152. [Google Scholar]

- Schensul J.J., LeCompte M.D. Walnut Creek; CA: 2010. Designing and conducting ethnographic research: An introduction Altamira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spengler J.O., Floyd M.F., Maddock J.E., Gobster P.H., Suau L.J., Norman G.J. Correlates of park-based physical activity among children in diverse communities: results from an observational study in two cities. Am. J. Health Promot. 2011;25(5):e1–e9. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.090211-QUAN-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spittaels H., Foster C., Oppert J. Assessment of environmental correlates of physical activity: development of a European questionnaire. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2009;6:39. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-6-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spittaels H., Verloigne M., Gidlow C. ‘Measuring physical activity-related environmental factors: reliability and predictive validity of the European environmental questionnaire ALPHA. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010;7:48. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon P.S., Zhou C., Sallis J.F., Cain K.L., Frank L.D., Saelens B.E. Home environment relationships with children's physical activity, sedentary time, and screen time by socioeconomic status. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012;26:88. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tappe K.A., Glanz K., Sallis J.F., Zhou C., Saelens B.E. Children's physical activity and parents' perception of the neighbourhood environment: neighbourhood impact on kids study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013;10:39. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-10-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veitch J., Salmon J., Ball K. Individual, social and physical environmental correlates of children's active free-play, a cross sectional study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010;2:7–11. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson S. Focus group research. In: Silverman D., editor. Qualitative Research, Theory, Method and Practice. Sage; London: 2004. pp. 178–199. [Google Scholar]

- Williams E.D., Steptoe A., Chambers J.C., Kooner J.S. Psychosocial risk factors for coronary heart disease in UK South Asian men and and women. J. Epidemiol. Comm. Health. 2009;63:986–991. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.084186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]