Abstract

Synthetic biology and the rational design of biological devices depend on the availability of standardized and interchangeable biological parts with diverse range of functions. Reliable access to different reading frames during translation has largely been overlooked as functionality for bioengineering applications. Here we report the construction and initial characterization of the first member of such a class of biological parts that conforms to the BioBrick Standard (RFC25), allowing its interchangeable use in biological devices. Using our standardized frameshifting signal consisting of a UUUAAAG slippery sequence, a 6 nt spacer and an engineered pseudoknot based on the infectious bronchitis virus pseudoknot PK401 embedded in a dual reporter construct, we confirm that the frameshifting activity is comparable to the previously published frequency despite the introduced sequence changes. The frameshifting activity is demonstrated using SDS-PAGE and fluorescence spectroscopy. Standardized programmable ribosomal frameshift parts with specific frameshifting frequencies will be of utility for applications such as double coding DNA sequences by expanding the codable space into the -1 frame. Programmed shifting into the -1 frame to bypass a stop codon allows labeling of a protein pool with a fixed stoichiometry of fusion protein, as well as the construction of multi-enzyme expression constructs with specific expression ratios. A detailed understanding of the structural basis of programmed frameshifting will provide the opportunities to rationally design frameshifting elements with a wide range of applications in synthetic biology, including signals that are regulated by small ligands.

Keywords: fusion proteins, frameshifting efficiency, programmed ribosomal frameshifting, part class, synthetic biology, standardized part, variable tagging

Abbreviations

- IPTG

isopropyl-β-D-galactopyranoside

- PMSF

phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate.

Introduction

Gene expression is a 2-step process, during which the genetic information is first transcribed into messenger mRNA (mRNA) which is then translated by the ribosome into the corresponding protein. It is critical that the reading frame of the mRNA is maintained during translation to ensure a direct correspondence between gene and protein. However, several viruses and bacteria contain gene sequences which result in mRNAs that induce programmed frameshifting events, enabling the respective host organism to code outside of the initial reading frame.1 A variety of programmed frameshifting signals have been reported with frameshifting frequencies ranging from less than 1% to over 80%.2,3 The commonality among all these signals is the presence of a “slippery” sequence on which the recoding event occurs and that is followed by a spacer and stalling inducing element.4 Furthermore, frameshifting is not limited to the -1 frame, as -2 and +1 frameshifts have also been observed.5-7 To determine frequency and mechanistic details of frameshifting, reporter constructs (e.g. dual luciferase reporters) have been employed previously. These studies have shown that programmed ribosomal frameshifting (PRF) can function in a variety of sequence backgrounds. However, the lack of standardization of these reporter constructs, including the sequence of the frameshifting element itself as well as its sequence context, poses a challenge for detailed mechanistic analyses and the comparability of reported results. The use of dual reporter constructs that are rationally designed using the standardized assembly approaches often applied in synthetic biology would help alleviate these problems and allow for easy design, construction and increased reproducibility across different studies. In addition, the availability of a family of standardized DNA parts that reliably mediate programmed ribosomal frameshifting will be of great interest and utility in synthetic biology and the rational design of genetic devices that execute desired functions within a host cell.

Results and Discussion

We wanted to test if the -1 PRF functionality can be made available as a standardized and interchangeable class of DNA sequences or parts, similar to promoters, ribosomal binding sites or protein coding regions which can subsequently be assembled into genetic devices, such as dual reporter systems or protein expression constructs. To allow for the interchangeability and easy construction of devices using these parts, standards have to be established. Several such standards have been developed over the last 10 years.8 The majority of these standards share the introduction of so-called prefix and suffix sequences preceding and directly following the sequence of interest which play important roles during the assembly of these standardized DNA parts into a genetic device. To allow for certain restriction enzymes to cleave only within this region, their respective recognition sequences have to be excluded from the actual part sequence. Furthermore, after combining 2 parts often the restriction sites are destroyed and a ‘scar’ sequence between the parts is created, allowing the repeated use of the respective restriction enzyme during assembly of lager devices. Here, 2 major types of scar sequences are used: some allow for the translation of the scar and downstream sequence by the ribosome, while others introduce a stop codon preventing this read-through. Among these assembly standards the BioBrick standard is one of the most successful ones, with thousands of BioBrick conforming parts available through the Registry of Standard Biological Parts (http://parts.igem.org; the respective accession codes are used throughout the text). We chose to design a standardized -1 PRF part and a corresponding dual reporter device using the well-characterized BioBrick assembly standard variant RFC25 (http://parts.igem.org/Help:Standards/Assembly/RFC25) developed for the generation of fusion proteins. We base this first member of the standardized frameshifting part family (FrameChanger, Fig. 1) on a -1 PRF signal found in the infectious bronchitis virus (IBV).4

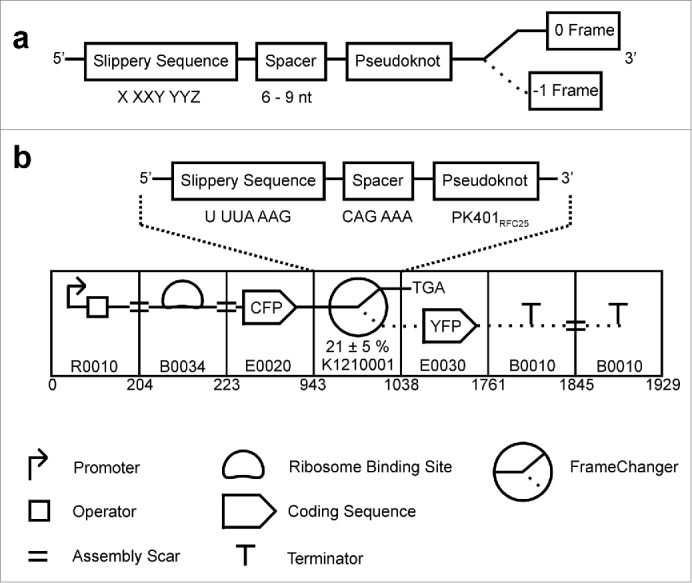

Figure 1.

Construction of the programmed -1 ribosomal frameshifting device. (A) Consensus elements constituting the used -1 frameshifting element. (B) Schematic illustration of the constructed -1 frameshifting reporter device (BBa_K1210000). Each of the parts is represented according to the Synthetic Biology Open Language visual standard (www.sbolstandard.org), and the Registry of Standard Biological Parts part number (http://parts.igem.org) are shown. The proposed SBOL standard frameshifting symbol includes the measured frameshifting frequency.

Frameshifting signals

In order to demonstrate that standardized programmed ribosomal frameshifting signals can be used as a new biological part class for the design of genetic devices, including but not limited to dual reporter constructs, we designed a reporter device containing a -1 programmed ribosomal frameshifting signal based on the 3 consensus elements (Fig. 1A) summarized by Atkins et al.9 In such a frameshifting signal, the transcribed mRNA forms a pseudoknot structure downstream of the decoding site, which is separated by a linker sequence from a heptanucleotide sequence (the slippery sequence) where the -1 frameshift occurs and that typically has the following sequence X XXY YYZ (X, Y and Z denote different nucleotides, the initial reading frame is given by spaces). The pseudoknot structure slows the progression of the translating ribosome along the mRNA, providing the opportunity for the recoding event to occur. The spacer sequence (6 – 9 nt) is required for the correct positioning of the ribosome correctly over the slippery sequence.4,6

A BioBrick-conforming frameshifting signal

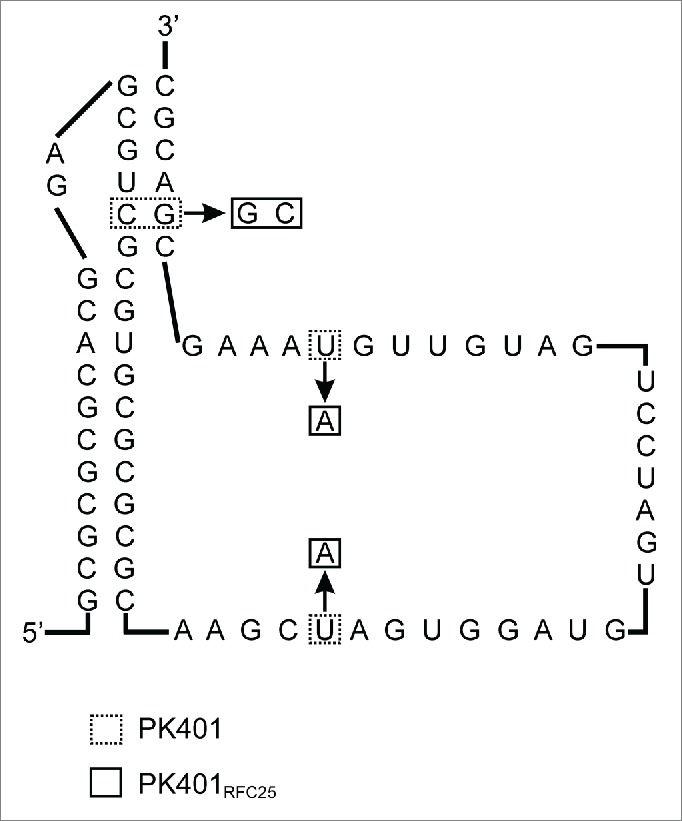

We use a frameshifting signal based on the well-characterized pseudoknot PK401 derived from the infectious bronchitis virus with a reported frameshifting frequency of 14% in Escherichia coli, as well as a slippery sequence that is highly efficient in E. coli.4,10,11 The published PK401 sequence was optimized by introducing nucleotide changes that reduce the number of rare codons encountered by the ribosome translating the sequence of the pseudoknot, maintain secondary structure, and exclude RFC25 incompatibles sequences, to yield a BioBrick (RFC25) standard conforming part (BBa_K1210001, Fig. 1B) containing the RFC25 prefix and suffix (PK401RFC25). To achieve this we changed 2 rare codons, a leucine codon in the 0 reading frame (CTA to CAA; nucleotide 996) and a rare serine codon in the -1 reading frame (TCG to TGG; nucleotide 980) along with a compensatory mutation (CGA to CCA; nucleotide 1025) downstream to maintain base pairing in the pseudoknot. Two stop codons (TAA) were changed to lysines (AAA) to prevent premature termination in the -1 reading frame; one located in the spacer sequence (nucleotide 959), and the other in loop 2 (nucleotide 1019). Finally, 2 thymidines (TT) were added following the pseudoknot (nucleotides 1032 and 1033) to put YFP into the -1 reading frame.

Construction of dual reporter frameshifting device

We also designed a reporter device (BBa_K1210000) to assess the frameshifting frequency of the modified PK401RFC25 pseudoknot (Fig. 1B). In this construct the gene for cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) is located upstream from the frameshifting signal followed by a TGA stop codon in the 0 frame or the gene for yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) in the -1 frame. To do so, we have removed the 2 TAA TAA stop codons at the end of CFP (BBa_E0020) to ensure translation continues through the PK401 pseudoknot. Therefore, translation of the 0 frame will result in a CFP fused to a short 33 amino acid peptide corresponding to the in-frame translation of the frameshift-signal sequence (99 nt) with a molecular weight of 30.6 kDa. However, when frameshifting into the -1 frame occurs, translation of the 0 frame stop codon (TGA) is bypassed and a fusion protein of 57.4 kDa is synthesized that contains CFP and YFP connected by a short 33 amino acid linker peptide (Fig. 1B).

Frameshifting activity

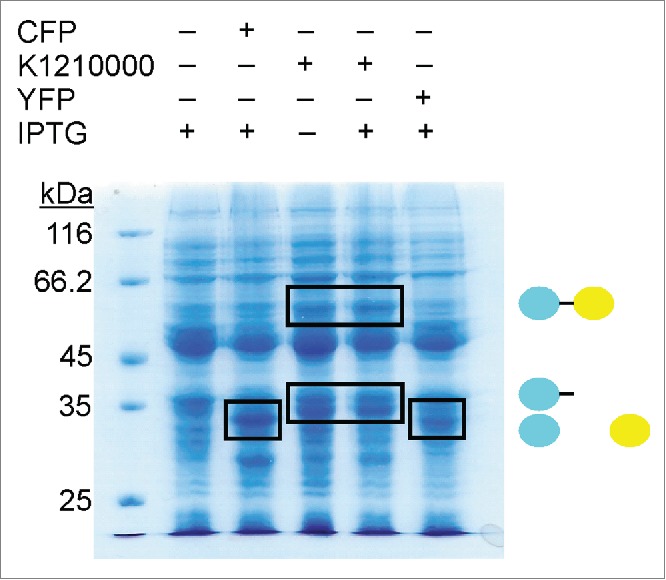

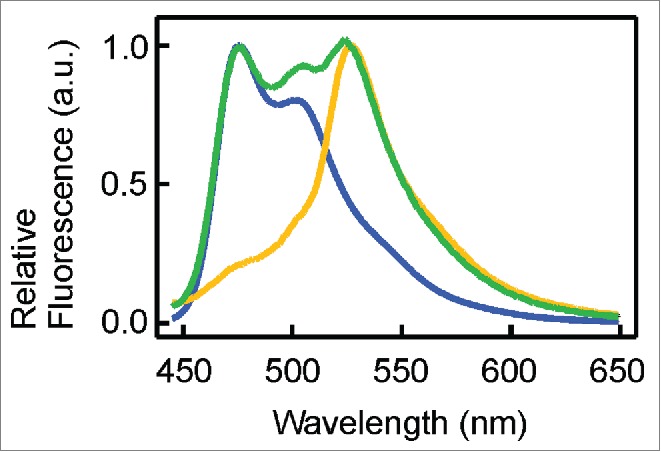

To confirm that our standardized -1 PRF signal (FrameChanger) functions as designed, we transformed our reporter device (BBa_K1210000) into E. coli DH5α cells and compared protein expression in the absence and presence of IPTG with the expression of CFP and YFP generated by BBa_K331033 and BBa_K331031 (Registry of Standard Biological Parts) using SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3). As expected, expression of CFP or YFP alone yields proteins with a size of approximately 30 kDa, whereas expression of our reporter device produces a protein of slightly larger size consistent with the expression of CFP harboring the small C-terminal extension caused by translation of the frameshifting signal. Moreover, our reporter device also produces a larger protein, approximately double the size of CFP, consistent with the size of the expected CFP-linker-YFP fusion protein. In order to estimate the frameshifting frequency of PK401RFC25 we used densitometry to compare the relative band intensities (Fig. 3) of the 60 kDa protein to that of the 33 kDa protein. The analysis yielded an estimated frameshifting efficiency of 21 ± 5%, consistent with the previously reported frameshifting efficiency of 14 ± 2% for the PK401 pseudoknot.4 This confirms that approximately 21% of the translated proteins were shifted into the -1 frame by the FrameChanger part, demonstrating its portability and robustness. To confirm that indeed CFP and YFP are expressed, we measured the fluorescence spectra of the corresponding cell lysates (Fig. 4). When excited at 430 nm not only is CFP fluorescence observed, as demonstrated by the overlap in fluorescence emission with the CFP standard, centered around (479 nm), but also YFP fluorescence (527 nm).

Figure 3.

Comparison of PK401RFC25 reporter device driven CFP and YFP expression. Equivalent amounts of cells containing CFP (BBa_K331033), YFP (BBa_K331031), BBa_K1210000 (+ / -IPTG) or BBa_K331035 (no-promoter YFP construct) were analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE. Black boxes indicate expressed protein products, including CFP (cyan) and YFP (yellow) at approximately 30 kDa, the non-frameshifted CFP product from BBa_K1210000 at approximately 33 kDa, and -1 frameshifted CFP-linker-YFP fusion product at approximately 60 kDa.

Figure 4.

Spectroscopic confirmation of CFP and YFP expression. CFP and YFP fluorescence spectra obtained from cells expressing CFP (BBa_K331033), YFP (BBa_K331031) or PK401RFC25 reporter device (BBa_K1210000). Fluorescence was excited near the excitation maximum of CFP (430 nm) and the emission was recorded from 445-650 nm (CFP, blue; YFP, yellow; BBa_K1210000, green). Spectra were normalized by dividing all data points in the spectrum by the value recorded at λmax = 527 nm.

Programmed frameshifts as a new class of parts

We propose a novel part class that enables programmable access to other reading frames during translation. We have successfully demonstrated the function of such a standardized frameshifting part in a dual reporter device. The use of different frameshifting elements such as alternative pseudoknots will allow for a variety of frameshifting frequencies or even frameshifting in response to a small signaling molecule.12 It will, for example, enable the compression of genomes and genetic devices through overlapped coding of 2 different gene products in different reading frames from a single DNA sequence. Viruses such as the Israeli acute paralysis dicistrovirus (IAPV) provide examples demonstrating the feasibility of this double coding strategy as the internal ribosome entry site not only facilities translation initiation but also has a propensity to induce a frameshift that allows the translation of another essential viral protein.13 A –1 PRF signal at the beginning of a coding sequence that contains a STOP codon in one frame and the rest of the protein in the -1 frame enables fine-tuning of protein expression levels during translation. Furthermore, switching the reading frame at the end of a coding sequence or even within a particular protein can enable the expression of 2 protein variants, for example a short (non-shifted) and a longer (shifted) variant expressed with an additional protein or domain fused to it. Using a combination of dual-coding and programmed ribosomal frameshifting will allow the expression of proteins with altered domain composition in a ratio determined by the frequency of frameshifting specific to the respective frameshifting element. Previous studies have used programed ribosomal frameshifting elements to monitor recombinant protein expression by tagging the target protein with enhanced GFP.14 We therefore believe that the reported frameshifting part constitutes the first member of a novel part class (FrameChanger) that is highly useful in synthetic biology. We have submitted the FrameChanger part (part number: BBa_K1210001) to the Registry of Standard Biological Parts, an open source repository for biological parts and devices. Availability of standardized programmed ribosomal frameshifting signals as biological parts, as well as a large number of freely accessible standardized gene expression devices will provide powerful tools for not only synthetic biology applications but also for the study of the molecular mechanism of frameshifting in vivo and in vitro.

Methods

Molecular biology

The 1929 nucleotide sequence of BBa_K1210000 (Fig. 1B) was synthesized (GENEWIZ Inc..) in pUC57-Kan containing prefix (gaattcgcggccgcttctagag) and suffix (tactagtagcggccgctgcag) sequences. The plasmid was propagated in E. coli DH5α cells (Invitrogen), purified, digested with EcoRI and PstI (Fermentas), and the resulting fragment subsequently ligated into a similarly digested standard BioBrick vector (pSB1C3) using T4 DNA ligase (Fermentas). The sequence of the obtained construct was confirmed by sequencing (GENEWIZ Inc.). BBa_K1210001 was constructed based on PK4014 by introducing 4 nucleotide substitutions (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Sequence of the BioBrick conform pseudoknot PK401 from infectious bronchitis virus pseudoknot. Boxed nucleotides were changed to convert the previously reported PK401 sequence4 into a BioBrick RFC25 conform sequence (PK402RFC25).

Protein expression

Plasmids containing the corresponding expression constructs were transformed into competent E. coli DH5α cells (Invitrogen) using heat shock. Subsequently, cells were incubated overnight at 37°C in 50 mL LB (Luria-Bertani) media containing Kanamycin (50 µg/mL). Obtained cultures were used to inoculate 500 mL of LB media to a starting optical density at 600 nm (OD600) near 0.05. The OD600 was monitored and expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG at an OD600 of 0.6. After 4 hours the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5000 x g, aliquoted, flash frozen, and stored at 80°C for further use. Leaky expression was observed for non-induced expression of the dual reporter device.

SDS-PAGE analysis

Frozen cell pellets were re-suspended in 80 µL 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.5 containing 5 M Urea and 20 µL SDS-PAGE gel-loading buffer (300 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 600 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 12% (w/v) SDS, 0.6% Bromophenol blue, 60% (v/v) Glycerol). The samples were then analyzed on a 12% SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue. Frameshifting frequency (FS%) was calculated based on SDS-PAGE band intensity (ImageJ) of the frameshifted (FS) CFP-linker-YFP fusion compared to the sum of FS CFP-linker-YFP and non-frameshifted (NFS) CFP protein (equation 1). Intensity (I) of each band was corrected for differences in protein size by dividing by the molecular weight (MW).

| (1) |

CFP and YFP fluorescence

Cell pellets were lysed using 1 mg/mL Lysozyme and 12.5 mg/g Sodium deoxycholate in Buffer A (50 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.0 at 4°C), 60 mM NH4Cl, 7 mM MgCl2, 300 mM KCl, 15% Glycerol, 7 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM PMSF). DNase was added and incubated for 15 minutes on ice followed by centrifugation at 3000 x g for 30 minutes. The supernatants were collected and centrifuged at 30 000 x g for 45 minutes. The resulting supernatants were then diluted 100-fold in Buffer A. CFP and YFP fluorescence were excited at 430 nm and emission spectra (445-650 nm) were recorded using a Quanta Master 60 fluorescence spectrometer (Photon Technology International). Spectra were normalized by dividing all data points in the spectrum by the value recorded at λmax = 527 nm.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Anthony Vuong, Justin Vigar and Fan Mo for their expert advice and help. This work was supported by Alberta Innovates Technology Futures.

References

- 1.Dinman JD. Mechanisms and implications of programmed translational frameshifting. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 2012; 3:661-73; PMID:22715123; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/wrna.1126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Recoding: Expansion of Decoding Rules Enriches Gene Expression, In Recoding: Expansion of Decoding Rules Enriches Gene Expression Atkins JF, Gesteland RF, Eds.2010 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caliskan N, Peske F, Rodnina MV. Changed in translation: mRNA recoding by-1 programmed ribosomal frameshifting Trends Biochem Sci 2015; 40:265-74; PMID:25850333; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tholstrup J, Oddershede LB, Sorensen MA. mRNA pseudoknot structures can act as ribosomal roadblocks. Nucleic Acids Res 2012; 40:303-13; PMID:21908395; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkr686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ivanov IP, Gesteland RF, Matsufuji S, Atkins JF. Programmed frameshifting in the synthesis of mammalian antizyme is +1 in mammals, predominantly +1 in fission yeast, but -2 in budding yeast, RNA 1998; 4:1230-8; PMID:9769097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin Z, Gilbert RJ, Brierley I. Spacer-length dependence of programmed -1 or -2 ribosomal frameshifting on a U6A heptamer supports a role for messenger RNA (mRNA) tension in frameshifting. Nucleic Acids Res 2012; 40:8674-89; PMID:22743270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Firth AE, Jagger BW, Wise HM, Nelson CC, Parsawar K, Wills NM, Napthine S, Taubenberger JK, Digard P, Atkins JF. Ribosomal frameshifting used in influenza A virus expression occurs within the sequence UCC_UUU_CGU and is in the+1 direction. Open Biol 2012; 2:120109; PMID:23155484; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1098/rsob.120109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casini A, Storch M, Baldwin GS, Ellis T. Bricks and blueprints: methods and standards for DNA assembly. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2015; 16:568-76; PMID:26081612; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm4014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atkins JF, Bjork GR. A Gripping Tale of Ribosomal Frameshifting: Extragenic Suppressors of Frameshift Mutations Spotlight P-Site Realignment. Microbiol Mol Biol R 2009; 73:178; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MMBR.00010-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansen TM, Reihani SNS, Oddershede LB, Sorensen MA. Correlation between mechanical strength of messenger RNA pseudoknots and ribosomal frameshifting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007; 104:5830-5; PMID:17389398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiss RB, Dunn DM, Shuh M, Atkins JF, Gesteland RF. Escherichia coli ribosomes rephase on retroviral frameshift signals at rates ranging from 2 to 50 percent. New Biologist 1989; 1:159-70; PMID:2562219 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta P, Kannan K, Mankin AS, Vazquez-Laslop N. Regulation of gene expression by macrolide-induced ribosomal frameshifting. Mol Cell 2013; 52:629-42; PMID:24239289; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.10.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ren Q, Wang QS, Firth AE, Chan MM, Gouw JW, Guarna MM, Foster LJ, Atkins JF, Jan E. Alternative reading frame selection mediated by a tRNA-like domain of an internal ribosome entry site. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109:E630-639; PMID:22247292; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1111303109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han SJ, Cho S, Lowehhaupt K, Park SY, Sim SJ, Kim YG. Recombinant tagging system using ribosomal frameshifting to monitor protein expression. Biotechnol Bioeng 2013; 110:898-904; PMID:23042497; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/bit.24740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]