Abstract

Functionalized fullerenes are becoming of wide interest to mediate photodynamic therapy (PDT) of diseases such as cancers and infections. We recently reported the synthesis of two new decacationic fullerene monoadducts: C60[>M(C3N6+C3)2]−(I−)10(LC14) and its derivative with a light-harvesting antenna conjugated as a C60[>CPAF-(MN6+C3)2]−(I−)10nanostructure (LC15). We studied the ability of these compounds to mediate PDT of human cancer cells in vitro when excited by UVA light or by white light. Here we report the synthesis of a new fullerene derivative C60[>M(C3N6+C3)2][>M(C3N6C3)2]−(I−)10(LC16 derived from LC14), as a malonatebisadduct containing a covalently-bound deca-tertiary amine arm. We investigated the relative abilities of the three compounds to generate singlet oxygen (1O2), hydroxyl radicals (HO·), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) after excitation by UVA or by white light. We used three different classes of pathogenic microbial cells (Gram-positive bacterium, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Gram-negative bacterium Escherichia coli, and fungal yeast Candida albicans). LC15 was the most powerful broad spectrum antimicrobial fullerenylphotosensitizer (FPS) followed by LC16 and LC14 was least powerful. Killing depended on both fullerene monoadduct concentration and light fluence. UVA was five times more effective than white light for killing, but not for generation of ROS and relative absorption was greater in white spectral region. Bacterial killing was not much inhibited by addition of azide anions and in some cases was potentiated. In the absence of oxygen, microbial photokilling was highly potentiated (up to 5 logs) by addition of azide anions. We conclude that molecular functional addends that encourage a Type-I electron-transfer mechanism increase the ability of photoactivated fullerene monoadducts to kill microbial cells. Oxygen-independent photokilling is possible with fullerene monoadducts in the presence of azide anions, probably mediated by azidyl radicals. UVA excitation may kill bacteria partly by an electron-transfer mechanism directly into bacteria as well as by ROS.

Keywords: Functionalized decacationic [60]fullerenes, antimicrobial photodynamic inactivation, reactive oxygen species, azide radicals, photoinduced electron transfer, oxygen independent photokilling

Introduction

Infections with multidrug-resistant (MDR) and pandrug-resistant (PDR) bacterial strains are considered an emerging threat to public health throughout the world, and are responsible for significant morbidity and mortality [1]. There is now a relatively rapid acquisition of antibiotic resistance by bacteria and extremely few antibiotics with new mechanisms of action are in the pipeline. The infections caused by antibiotic resistant strains are often exceptionally hard to treat due to the limited range of therapeutic options [2]. Therefore, there is a need for an immediate and all-out search for alternative antimicrobial methods against MDR strains towards which no resistance likely to develop [3–5]. Recently, Karen Bush et al. pointed out that novel non-antibiotic approaches for the prevention of and protection against infectious diseases should be considered high-priority research and development projects [6]. One of the most promising and innovative approaches in this respect is antimicrobial photodynamic inactivation (aPDI).

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) and aPDI employ a nontoxic dye termed a photosensitizer (PS) and harmless low-intensity visible light of suitable wavelength to match the PS absorption peak. These individually harmless elements can interact in the presence of molecular oxygen to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as singlet oxygen (Type-II) and hydroxyl radical (Type-I) [7]. At present, it is well accepted that PDT can inactivate all known classes of microorganism, including Gram-positive, Gram-negative bacteria, fungi and protozoa etc, whether in vitro or in vivo [3, 4, 8]. aPDI is thought to be equally effective (or even more effective) against multidrug-resistant than naïve species [9], and in addition the PDT treatment itself is unlikely to cause resistance, as damage by ROS is thought be via a non-specific killing mechanisms compared with antibiotics that generally inhibit a specific enzyme [10, 11]. The speed of action is rapid for aPDI (many logs killed over minutes) as compared with antibiotics that typically require many days or weeks to be effective, and this makes it easier to induce drug-resistance mutations.

The characteristics of the ideal PS are as follows: 1) low levels of dark toxicity; 2) its absorption bands located in the so-called optical window (600–900 nm) for sufficient tissue penetration of light; 3) relatively high absorption bands (>20,000–30,000 M−1cm−1) to minimize concentration of PS and low fluences of light needed to achieve the desired effect; 4) high triplet and singlet oxygen quantum yields. Additional requirements needed for antimicrobial PS are: 1) high selectivity for microbial cells over mammalian cells; 2) the ability to kill multiple classes of pathogen [12]. It has been found that compounds that fulfill these requirements are likely to have pronounced cationic charges. The most common chemical structures that have been employed as PS for aPDI purposes have been derived from tetrapyrrole compounds such as porphyrins, and synthetic dyes such as phenothiazinium salts. In recent years spherical C60 core-derived fullerenes that have been rendered cationic by functionalization have been studied as antimicrobial PS [11, 13, 14]. This development has been associated with rapid progress in the development of biomedical applications of fullerenes [15, 16].

Fullerenes are closed-cage molecules entirely composed of sp2-hybridized carbon atoms whose system of delocalized Π-electrons imparts a large absorption of visible light and which have a good quantum yield of a long-lived triplet electronic excited state [17]. Since fullerenes are highly insoluble in biological media they must be chemically functionalized to provide water solubility and to prevent aggregation [18]. Different hydrophilic or amphiphilic side chains or fused ring structures have been attached to the spherical C60 core. Attachment of addends containing a large number of cationic charges therefore plays a dual role of bacterial targeting and providing water solubility. This functionalization imparts a higher ability to produce singlet oxygen, hydroxyl radicals and superoxide anion upon illumination, and these reactive species have been proposed as effective PDT mediators in several applications [19]. Furthermore, fullerenes have a higher degree of photostability compared with PS based on the tetrapyrrole or phenothiazinium backbones. Moreover, the broad absorption spectrum allows them to be excited with a range of wavelength ranging from UVA (360 nm) to red (635 nm). For these reasons fullerenes have recently attracted significant amounts of interest [12, 20] as PS to mediate PDT of infections as well as cancer.

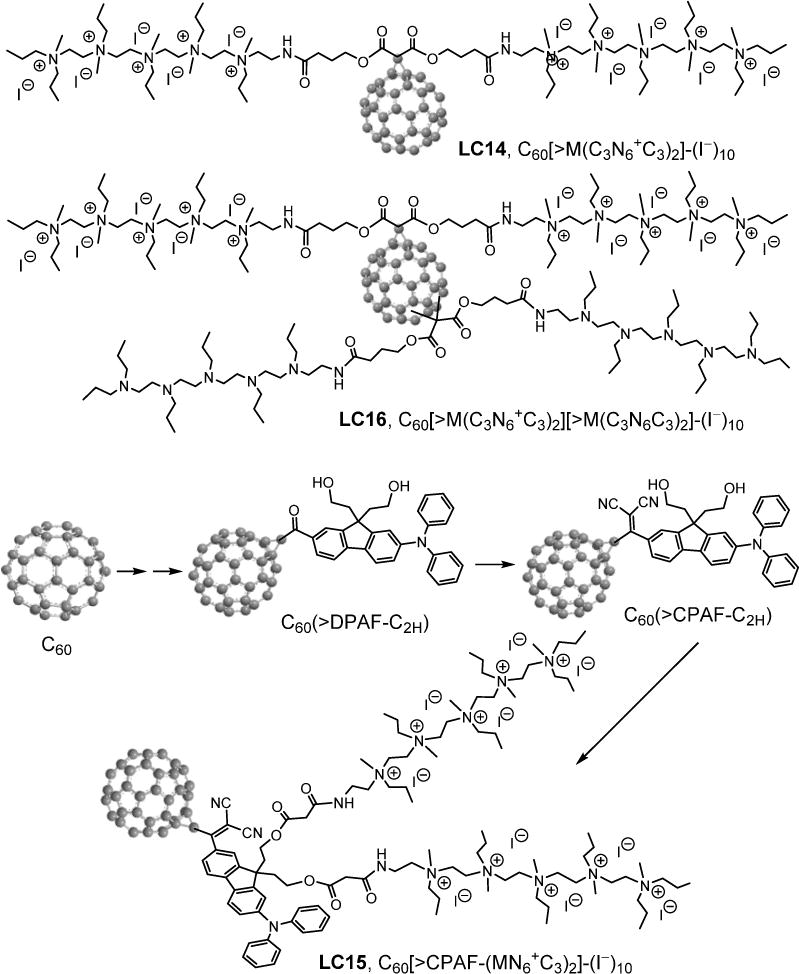

We recently reported the synthesis of two new decacationic malonate [60]fullerene, C60[>M(C3N6+C3)2]−(I−)10(LC14) and its modified derivative with a red light-harvesting antenna conjugated as a decacationic diphenylamino fluorenylmethano [60]fullerenyl monoadduct, C60[>CPAF−(MN6+C3)2]−(I−)10 (LC15, Figure 1) [21]. We studied the ability of these two compounds to mediate PDT of human cancer cells in vitro when excited by UVA light or by white light. Here we investigate the ability of these two compounds together with a third new fullerene derivative C60[>M(C3N6+C3)2][>M(C3N6C3)2]−(I−)10 (LC16 derived from LC14, Fig 1), as a malonate bisadduct containing a covalently-bound deca-tertiary amine arm, to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) using specific assays, and their ability to kill three different classes of pathogenic microbial cells [Gram-positive bacterium, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Gram-negative bacterium Escherichia coli, and fungal yeast Candida albicans] when excited by either UVA or by white light. Addition of sodium azide and oxygen removal was used to investigate the photochemical mechanisms of microbial killing.

Figure 1.

The structure of fullerene monoadducts LC14, LC15 and LC16.

Materials and Methods

Design and synthesis of [60]fullerene derivatives

The Gram-positive and Gram–negative bacterial cell surface is covered by a blanket of many anionic carboxylic acid residues outside the cytoplasmic membrane(s) as a part of either teichuronic or lipoteichoic acid moieties in the peptidoglycan layer or lipopolysaccharide structures, respectively [22–24]. The anionic shielding due to the high density of negative charges located at these bacterial surface areas allows us to differentiate bacteria from normal human cells. It also prohibits the penetration of some neutral and anionic PSs resulting in marked resistance to photodynamic inactivation with lowered aPDI efficiency [25]. Conversely, the anionic charges should attract cationic PS by simple static charge interaction. The interaction can be multiplied by attaching a string of cationic charges to a PS molecule to increase binding to bacterial cells and enabling enhanced penetration through the outer barrier of Gram-negative bacteria [26] and leading to improved PDT-induced inactivation [3]. This strategy motivated us to design new fullerenyl photosensitizers (FPS) using a well-defined pentacationicmethyl quaternary ammonium N,N′,N,N,N,N-hexapropyl-hexa(aminoethyl)amine as the alkyl C3N6+C3 arm synthon moietyto build the nanostructure of polycationic FPS monoadducts. The synthetic approach enabled covalent incorporation of a relatively large number of cations on a single functionalized alkyl addend to C60 without much disturbance of the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energy configuration of fullerene cage and, thus, its intersystem crossing efficiency (~100%) of excited singlet to triplet states [27]. We hypothesized that a FPS carrying ten cations as a decacationic chain could optimize surface interactions between FPS and the bacteria cell wall for antimicrobial targeted treatments. The decacationic modification also leads to conversion of highly hydrophobic C60 cage to amphiphilic showing sufficient hydrophilicity and largely enhanced solubility in water that facilitates the drug delivery of the resulting fullerenyl derivatives.

The first highly water-soluble decacationic [60]fullerenyl malonate monoadducts C60[>M(C3N6+C3)2]−(I−)10 (LC14) as a decaiodide was synthesized by a modified procedure as reported previously [14]. It required the attachment of two alkyl ammonium multi-salts C3N6+C3 to a malonate-linker moiety as a doubly-armed malonate ester precursor C3N6+C3-malonate-C3N6+C3 addend. Synthesis of this addend was accomplished by the ring-opening reaction of γ-butyrolactone using C3N6 as the nucleophile in CH2Cl2 in the presence of Lewis acid BF3·Et2O to afford 4-hydroxy-[N,N′,N,N,N,N-hexapropyl-hexa(aminoethyl) butanamide (C3N6C3−OH), followed by an esterification reaction with malonyl chloride in the presence of pyridineto form neutral C3N6C3-malonate-C3N6C3 addend (supporting information). Subsequent quaternization reaction with an excess of iodomethane affords C3N6+C3-malonate-C3N6+C3 in a high yield, prior to its covalent attachment to C60, via cyclopropanation reaction [28]. A similar cyclopropanation reaction was carried out with LC14 and one molar equivalent of the second C3N6C3-malonate-C3N6C3 addend to give the corresponding bisadduct C60[>M(C3N6+C3)2][>M(C3N6C3)2]−(I−)10 (LC16) (see supporting information).

In the case of the decacationic LC15 synthesis, a new precursor C60-(antenna) diol, C60(>DPAF-C2h) monoadduct (Fig 1 and supporting information) was used for the covalent linkage of two C3N6+C3-malonate arms via the reaction with Meldrum’s acid in toluene toluene, followed by N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC). More importantly, the primary difference between LC15 and LC14 is the covalent incorporation of a visiblelight-harvesting antenna moiety CPAF-C2 providing enhanced photo-absorption at 450–550 nm where the C60 cage has relatively low absorption. The ability of the CPAF-C2 antenna to undergo photoexcited electron-donation to the C60 electron-acceptor cage in LC15 allows switching of the dominant triplet energy transfer-based type-II photochemistry in LC14 to the anionic (C60>)−· radical-derived Type-I photochemistry. Conversion of the keto functional group of C60(>DPAF-C2h) to the corresponding highly electron-withdrawing 1,1′-dicyanoethylenyl group of C60(>CPAF-C2h) (Fig 1) was carried out by the reaction with malononitrile in the presence of a Lewis acid TiCl4 in pyridine–chloroform. This structural change increased the intramolecular electron polarization going from the electron-rich diphenylamine moiety to the C60 cage to favor the photoinduced intramolecular electron-transfer from the CPAF-C2 donor to C60. Furthermore, incorporation of ten counter iodide anions (I−) to LC15 may also allow the photoinduced oxidation of iodide via electron-transfer to either excited fullerene cage [1C60* or 3(C60>)*] or (CPAF-C2)+· in aqueous media, leading to further formation of fullerenyl anion radical intermediate (C60>)−·. This anionic radical intermediate can serve as the precursor for the generation of superoxide radical and subsequent generation of hydroxyl radicals.

Sample preparation procedure and conditions for transmission electron microscopic (TEM) measurements

As a general procedure, a sample of LC-x was dissolved in dimethylacetamide (DMA) under ultrasonication for a period of ~5 min, giving a stock solution with a concentration of 2.0 mM. A portion of this solution was then diluted by H2O to pre-determined concentrations of 1.0, 10, and 100 μM for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) measurements. Carbon-copper film grids with a 200 meshsize were used for topographical determination of the self-assembled nanostructures by TEM. Sample deposition was carried out by coating the grid with the solutions prepared above, followed by freeze-drying under vacuum to retain to the shape of nanovesicles on the grid without aggregation.

Microorganisms and culture conditions

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Escherichia coli K-12 (both wild type), were used. Planktonic bacterial cells were cultured in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth with aeration at 37°C. Exponential cultures obtained by re-culturing stationary overnight cultures were used for all experiments. Candida albicans (DAY286 reference strain was a gift from Aaron Mitchell, Department of Microbiology, Columbia University, New York) and was routinely cultured in yeast peptone dextrose (YPD) with aeration at 30°C overnight. MRSA and E. coli were grown in fresh medium for approximately 2–3h. All three broth cultures were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 2 min (centrifuge 5417 C; Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) and resuspended in 0.5 ml PBS. The concentrations were then adjusted to the appropriate values for the experiment by measuring the optical density. Bacteria were used at a cell density of 108CFU/ml (OD600 of 0.5) and C. albicans at a cell density of 107 CFU/ml (OD570 of 0.65) [29].

Light sources

We used two light sources. Firstly a white light source (Lumicare, Newport Beach, CA) fitted with a light guide containing a bandpass filter (400–700 nm) adjusted to give a uniform spot of 4.0 cm in diameter with an irradiance of 150 mW/cm2 as measured with a power meter (Model DMM 199 with 201 Standard head, Coherent, Santa Clara, CA). Secondly UVA irradiation was delivered by an ultraviolet (Woods) exam lamp (Model UV 501, Burton Medical, Chatsworth, CA). Emission spectrum measurement of this lamp by a spectroradiometer (SPR-01; Luzchem Research, Inc., Ottawa, ON, Canada) showed a peak emission at 365 nm. The irradiance was adjusted to 30 mW/cm2by manipulating the distance between the UVA lamp and the irradiated target and measured using a model IL-1700 research radiometer-photometer (International Light, Inc., Newburyport, MA).

Photodynamic inactivation studies

For fluence-dependent experiments, cells suspensions (described above) were incubated with either LC14, LC15, or LC16 each in 10 μM concentration for1.0 h at 37oC in the dark. Aliquots (1.0 ml) were transferred to a 24-well plate and illuminated by UV (with different doses, 10J/cm2, 20J/cm2, 30J/cm2, and 40J/cm2) and white light (50J/cm2, 100J/cm2, 150J/cm2 and 200J/cm2) at room temperature. For concentration-dependent experiments, cell suspensions were incubated with fullerenes at 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 μM concentrations for 1.0 h and then either left in dark for 22 min or excited with UVA at 40 J/cm2 or with white light at 200 J/cm2 (each taking 22 min).

At the completion of each stage of illumination, the contents of the wells were well mixed before sampling. Aliquots (100μl) were taken from each well to determine CFU. The aliquots were serially diluted 10-fold in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to give dilutions of 10−1 to 10−5 times in addition to the original concentration; then, 10μl aliquots of each of the dilutions were streaked horizontally on square BHI or YPD for Candida plates by the method of Jett and colleagues [30]. Plates were streaked in triplicate and incubated for 12 to 36 h at 37°C (or 30°C for 48h for Candida) in the dark to allow colony formation.

Control groups included cells that were treated with light alone (no fullerenemonoadducts added), and cells treated with fullerenemonoadducts (no light) as the dark control. Survival fractions (SF) were routinely expressed as ratios of CFU of microbial cells treated with light and fullerenemonoadducts, or treated with fullerenes in the absence of light, to CFU of microbes treated with neither.

Effect of added NaN3 on LC-x-mediated PDT killing of bacteria

NaN3 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals. Based on our previous study [31], we chose 10mM as the final concentration of NaN3 in the present study. Suspensions of bacteria (108/ml) were incubated in the dark at room temperature for 1.0 h with LC-x and immediately before the light we added 10mM NaN3 in pH 7.4 PBS. PDI was then carried out as described above.

Oxygen independent PDI

Microbial incubation was performed as described above and 10mM NaN3 added after 1.0 h if required. One-ml aliquots were transferred to quartz cuvettes (Model32Q10, StarnaCells Inc, Atascadero, CA) containing a magnetic stirrer and resealed with a rubber septum in the dark. Cuvettes allowed O2-free samples to be irradiated without exposure to ambient air. The septum was pierced with a hollow needle connected to a N2/Ar line and samples were then bubbled with 75%N2/25% Ar gas at least for 45 min. Samples were irradiated with UVA light source to deliver 10–40 J/cm2 at an irradiance of 7.0 mW/cm2 or a white light source to deliver 50–200 J/cm2 at an irradiance of 150mW/cm2, separately. Each cuvette was opened and serially diluted after a single fluence had been delivered.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation assay using fluorescent probes (SOSG and HPF)

LC-x solutions were diluted to a final concentration of 5.0μM per well in PBS in a 96-well plates, and 3′-(4-hydroxyphenyl) fluorescein (HPF) or singlet oxygen sensor green (SOSG) (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, USA) was added to each well at a final concentration of 5.0μM. All groups were illuminated simultaneously, and light (UVA or white) was delivered in sequential doses of 0–40J/cm2. HPF probe (excitation/emission=525/492nm) was employed for detection of HO· via quinone formation with the detection sensitivity reported to be roughly 145- and 90-fold higher for HO· than for 1O2 and O2−·, respectively [32]. SOSG probe (excitation/emission=505/525nm) which is highly selective for singlet oxygen(1O2) was used for detection the ability of LC-x to produce 1O2 [33]. A microplate spectrophotometer (Spectra Max M5, Molecular Devices) was used for acquisition of fluorescence signals in the “slow kinetic” mode. Increasing fluences (J/cm2) were delivered using either white light at 150 mW/cm2 or UV at an irradiance of 7.0mW/cm2. Each time after an incremental fluence was delivered, the fluorescence was measured. Each experimental group contained four wells.

Amplex red assay for hydrogen peroxide

Amplex red hydrogen peroxide/peroxidase assay kit was purchased from Invitrogen, and was used to detect the production of H2O2 from LC-x mediated PDT. The colorless probe Amplex red (10-acetyl-3,7-dihydroxy-phenoxazine) reacts with H2O2 in the presence of peroxidase and forms resorufin (7-hydroxy-3H-phenoxazin-3-one) [34]. The detection process after LC-x mediated PDT was according to manufacturer’s instructions. The reaction systems contained LC-x (5.0 μM) with or without added 10 mM NaN3 with 50μM Amplex Red reagent and 0.1U/ml horseradish peroxidase (HRP) in Krebs–Ringer phosphate (consists of 145 mMNaCl, 5.7 mM Na3PO4, 4.86 mMKCl, 0.54 mM CaCl2, 1.22 mM MgSO4, 5.5 mM glucose, pH 7.35.). A fluorescence microplate reader (excitation 530 nm and emission ~590 nm) was used to measure incremental fluorescence after an incremental fluenceof UV or white lightwas delivered. Controls were (1) LC-x + NaN3in dark, (2) NaN3+ light, and (3) Amplex red alone. Each experimental group contained four wells.

NBT assay for superoxide

Nitroblue tetrazolium [NBT; 2,2′-bis (4-nitrophenyl)-5,5′-diphenyl-3,3′-(3,3′-dimenthoxy-4,4′-diphenylene)ditetrazolium chloride; Sigma-Aldrich] is a yellow compound that is reduced by O2−· to form an insoluble blue formazan deposit [34]. Because NBT is difficult to dissolve, a small amount of methanol was used to dissolve the NBT before diluting into water to make the final concentration of 6.0 mM. The reaction system contained LC-x and NBT and incremental absorbance was measured after shining fluences of UV or white light. Because NaN3 can react with NBT in the dark, we did not test the addition of NaN3 and LC-x mediated PDT. The NBT reduction was followed at the isosbestic point of formazan formation 585nm [35].

Statistical analysis

Each value is the mean of three separate experiments with an error bar that reflects the standard deviation (SD). All results are expressed as the mean±SD. Differences between means were assessed for significance by one-way ANOVA and differences between the slopes of killing curves were evaluated using the linear regression analysis function contained in the GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego, CA). P values of less than 0.05 (P<0.05) were considered significant.

Results

Molecular self-assembly and optical absorption characterization of decacationicfullerenylnanomolecules

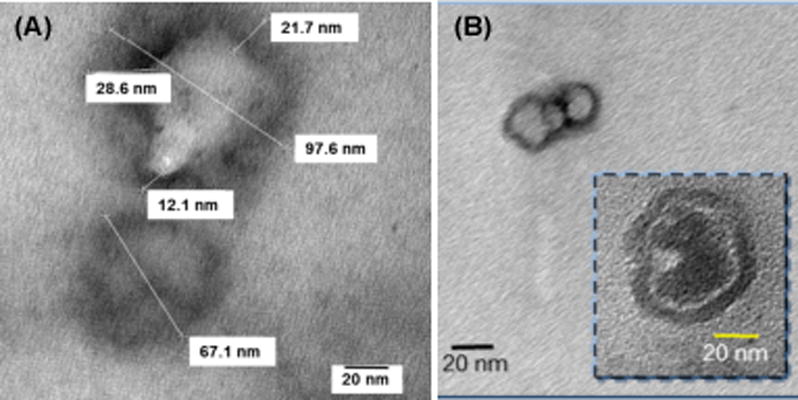

The attachment of two highly water-soluble pentacationic C3N6+C3 arms to a highly hydrophobic C60 cage of LC14 and LC15 rendered the resulting structures to be amphiphilic. A higher relative hydrophobic/hydrophilic volume-size ratio of LC14 than LC15 led to better water solubility for LC14 that exhibited no detectable bilayered fullerosome formation at concentrations lower than 10−5–10−6 M, therefore the nanostructures must be limited to only very small clusters. The partial formation of fullerosomes of LC14 was observed at concentration of 100 μM, as shown in Fig 2A.The average size of these nanovesicleswas estimated to be roughly 50–100 nm in diameter with the thickness of the outer membrane layer (diffuse dark area) measured to be roughly 12–20 nm. This thickness matches well with double the combined length of the C60 cage and two fully stretched C3N6+C3 arms along with ten iodide anions, forming the width of a bilayer. A similar average dimension of fullerosome nanovesicles derived from LC15 was also found, as shown in Fig 2B, with a more clearly defined darker membrane area. Similarity the membrane thickness of Figs 2A and 2B (inset, as double fullerosomes) was indicative of the preferred parallel orientation of hydrophobic C60(>CPAF-Cn) moieties in the membrane layer resulting in it being only slightly wider than t LC14, but more denselypacked.

Figure 2. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) micrographs showing images of fullerosome nanoparticles derived from.

(A) C60[>M(C3N6+C3)2]−(I −)10 (LC14) and (B) C60[>CPAF-(MN6+C3)2]−(I−)10 (LC15), collected at 100 μM concentration in DMF–H2O (1:20).

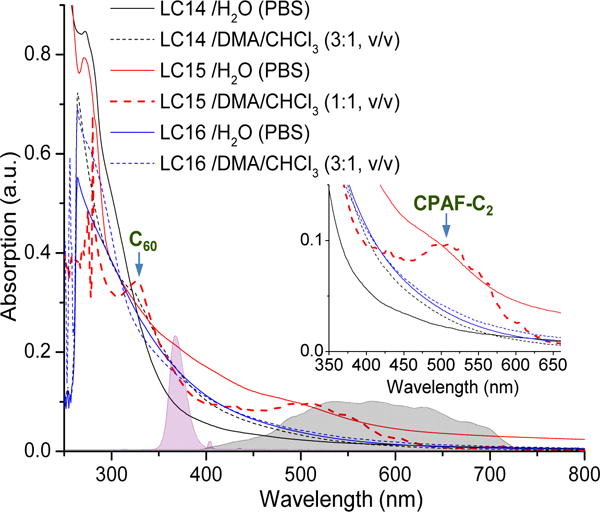

The effect of the molecular packing into self-assembled fullerosomes can be seen clearly on the UV-vis spectrum of LC15 in water (Fig 3) at a concentration of 1.0 × 10−5M displaying broad band absorptions in a monotonically decreasing curve with red-shifted peaks located at wavelengths 280–500 nm, as shown in the inset of Fig 3. As compared with fully monomeric LC15 in DMA–CHCl3 (1:1, v/v) at the same concentration, two absorption bands corresponding tomonofunctionalized C60> cage and CPAF-C2 antenna moieties were detected at λmax(ɛ) 328 (5.2 × 107), and 510 (1.4 × 107 cm2/mol), respectively, in the organic solution spectrum. As far as the packing configuration is concerned, we assume that two pentacationic C3N6+ arm attachments on a planar CPAF chromophore of LC15 at the C9fluorene-ring carbon position should give some hindrance to prohibit parallelaromatic CPAF–CPAF stacking in the membrane of the fullerosome. Therefore, the stronger hydrophobic–hydrophobic interactions of C60–C60 cages should be the dominant factor directing the orientation of LC15 nanostructures that is consistent with the observed high absorption extinction coefficients at 350–450 nm. This region overlaps well with the emission bands of UVA (filled purple peak band of Fig 3) and white (filled blue peak band of Fig 3) light sources used in this study. It was important to determine the relative photon absorptions integrated over these wavelength ranges, as the biological and photochemical effects were very different depending on the excitation wavelength. The overall absorption extinction coefficient ratios of two lights (UVA and white) by LC14, LC15, and LC16 in H2O (PBS) were calculated from the corresponding UV-vis spectra in Fig 3 and summarized in Table 1.

Figure 3.

UV-vis spectra of LC14, LC15 and LC16 with the emission spectrum of two light sources (UVA and white) indicated by the corresponding solid filled bands.

Table 1.

Absorption extinction coefficient ratios of UVA and white lights by LC-x monoadducts in H2O (PBS) calculated from the corresponding UV-vis spectra in Fig 3.

| White 691–479 nm | UVA 380–361 nm | |

|---|---|---|

| LC14 | 3.21 | 1.70 |

| LC15 | 12.3 | 3.98 |

| LC16 | 5.10 | 2.89 |

The relative area integration was over the wavelength range at the half-peak width of the light emission band.

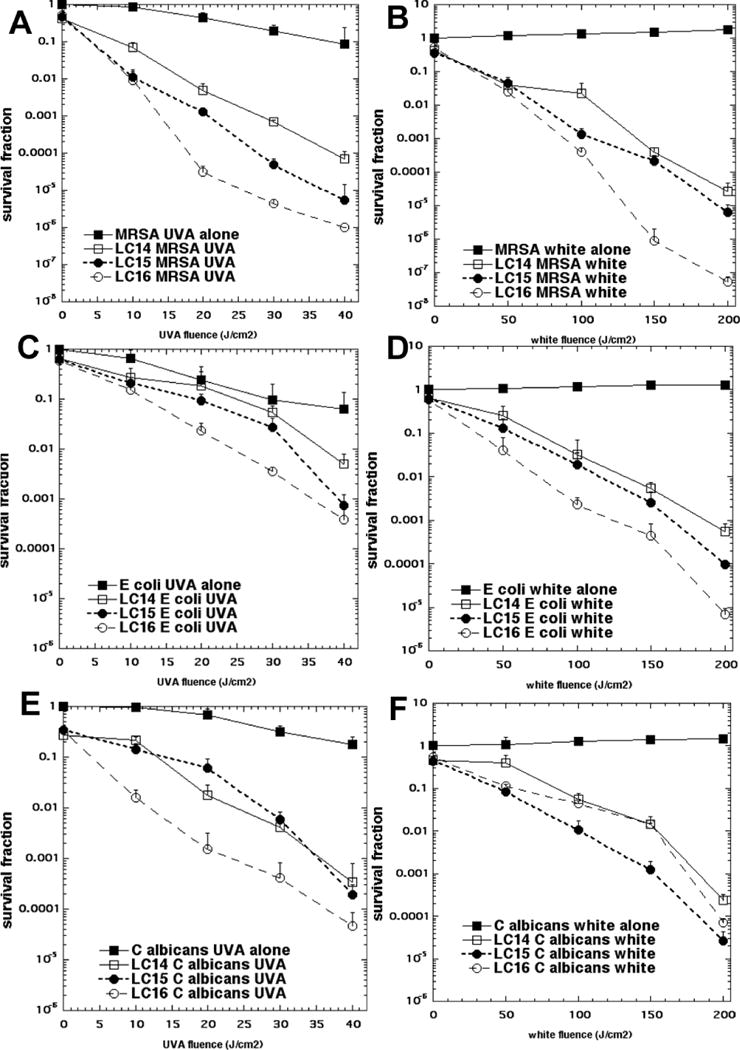

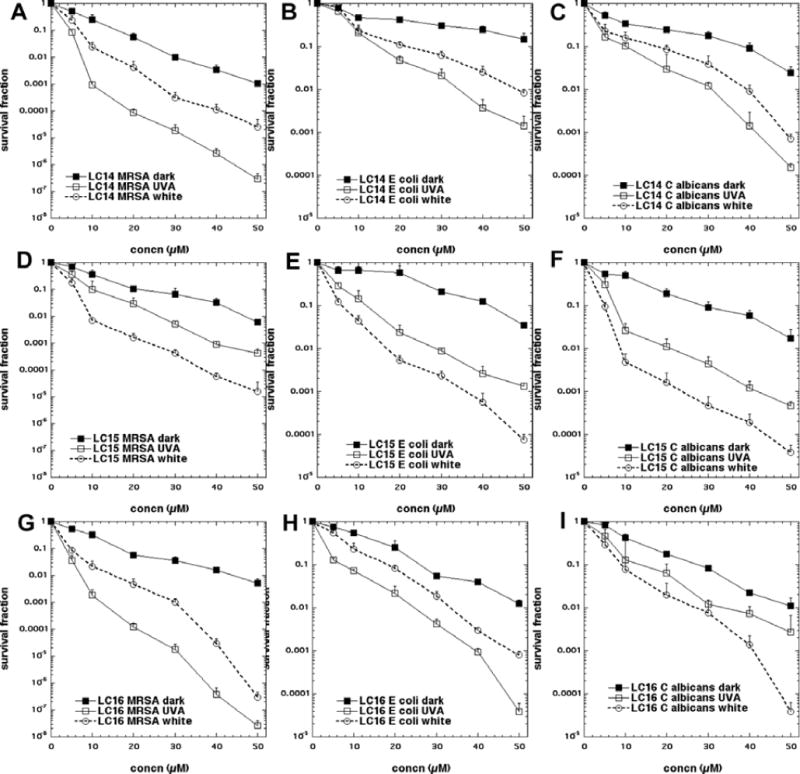

Antimicrobial PDI mediated by decacationic fullerenemonoadducts; dependence on delivered light dose

The bacteria killing data are presented in Fig 4 using a standard fullerene concentration of 10 μM and varying the dose (fluence in J/cm2) of either white or UVA light. We found that UVA light was approximately 5 times more effective than white light; therefore we varied the fluence from 0 up to 40 J/cm2 for UVA light and from 0 to 200 J/cm2 for white light. In Figs 4A and 4B, it can be seen that for the Gram-positive MRSA (irrespective of whether UVA or white light was used for excitation) there was a fluence dependent killing with the highest fluence giving almost 8 logs of bacterial killing (equivalent to eradication). In both cases the order of effectiveness was LC16 > LC15 > LC14 with about a 1 log increase in killing when going from one compound to the one that was next more powerful.

Figure 4. Light fluence-dependence of photoinactivation of microbial cells by 10μM fullerene monoadducts (light alone, LC14, LC15 and LC16 incubated for 1 h).

(A) MRSA and UVA light; (B) MRSA and white light; (C) E. coli and UVA light; (D) E. coli and white light; (E) C. albicans and UVA light; (F) C. albicans and white light.

In Figs 4C and 4D are presented the analogous data with the killing of Gram-negative bacteria E. coli. This species was killed somewhat less than MRSA, but there was still over 3 logs of killing with the highest dose of UVA light and over 4 logs of killing with the highest fluence of white light. The order of effectiveness was the same as that found for MRSA; for both wavelengths of light i.e. LC16 > LC15 > LC14.

In Figs4E and 4F, we show the killing obtained with the fungal yeast Candida albicans. The killing was somewhat higher than that seen for E. coli with the highest fluence of both wavelengths giving 4 or more logs of killing. Interestingly, although the order of activity of the three compounds for UVA excitation was the same as that found for the other microbes (LC16 > LC15 > LC14), the order seen for white light excitation was different, LC15 > LC16 > LC14.

Dependence of antimicrobial PDI on fullerene monoadduct concentration

It is necessary when carrying out in vitro antimicrobial PDI experiments to demonstrate the increase of microbial killing when both the concentration of PS as well as the light dose is increased. Moreover increasing the concentration of fullerene will allow comparison between the dark toxicity and the phototoxicity of the different compounds to be evaluated. This data is presented in Fig 5. In Figs 5A–5C it can be seen that for LC14 there was about 1–2 logs of dark toxicity towards the three different microbes and that in every case UVA light gave more killing than white light (by 2 logs for MRSA and 1 log for the other species) given that the UVA fluence was 5 times lower (40 J/cm2) than the white light fluence (200 J/cm2). In Figs5D–5F are shown the analogous results for LC15. It can be seen that the dark toxicity was somewhat lower than that seen for LC14 for MRSA, but comparable for the other species. Remarkably for all three microbes, white light gave more killing than UVA light when used to excite LC15. In Figs 5G–5I the concentration response to PDI with LC16 are displayed. Dark toxicity was similar to that seen for the other compounds. For MRSA (Fig 5G) and for E. coli (Fig 5H) UVA excitation gave more killing than white light, but for C. albicans(Fig 5I) the situation was reversed, with white light giving more killing than UVA.

Figure 5. Concentration-dependence of photoinactivation of microbial cells by fullerene monoadducts (dark, excited by 40 J/cm2 of UVA or by 200 J/cm2 of white light).

(A) MRSA and LC14; (B) MRSA and LC15; (C) MRSA and LC16; (D) E. coli and LC14; (E) E. coli and LC15; (F) E. coli and LC16; (G) C. albicans and LC14; (H) C. albicans and LC15; (I) C. albicans and LC16;

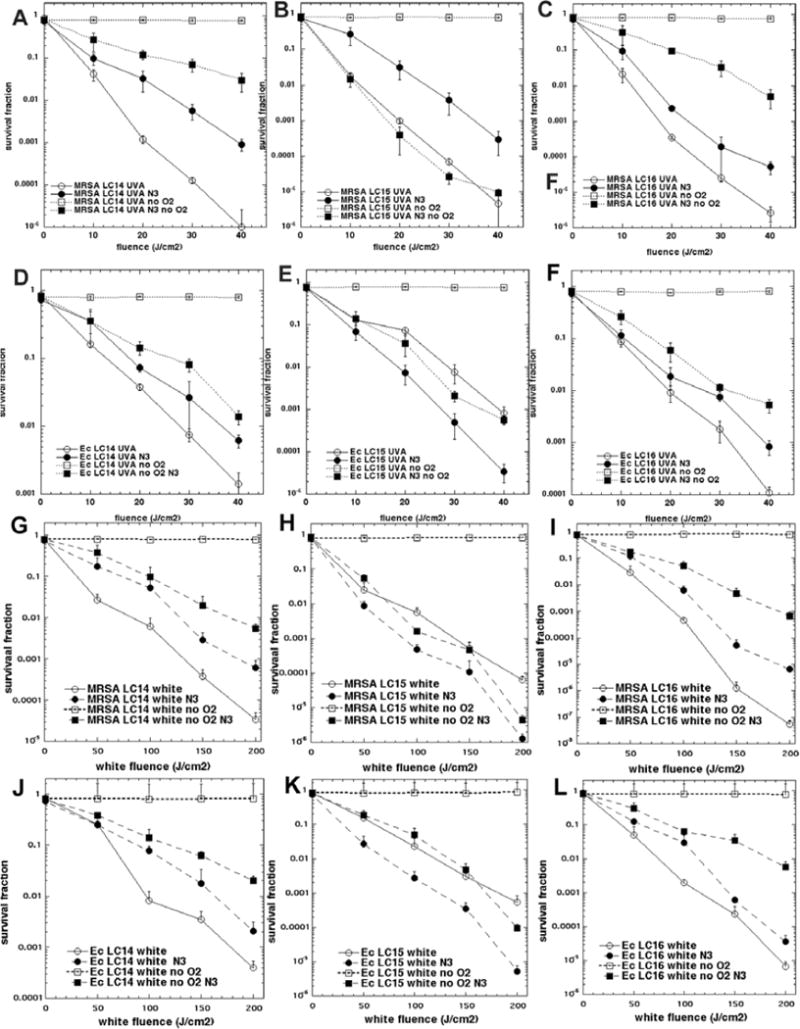

Effect of addition of azide (N3−) on microbial killing both in air and in absence of oxygen

These studies were only carried out on the two bacterial species (MRSA and E. coli) and not on the fungal species Candida because it is at present uncertain if azide anion can penetrate into the eukaryotic Candida cells. Figures 6A–6C (UVA light) and 6G–6I (white light) show the data achieved with MRSA, and Figs 6D–6F (UVA light) and 6J–6L (white light) show the data obtained with E. coli. Overall there was very little inhibition by azide when PDI was carried out in the presence of oxygen (a maximum of 2 logs inhibition in Fig 6A, more generally less than 1 log) and in the case of LC15 there was actually potentiation of killing (0.5 to 1 log) (Figs 6E, 6H, and 6K). When PDI was carried out in absence of oxygen there was complete abrogation of bacterial photokilling in every case as might be expected for an oxygen dependent photodynamic process. Remarkably, when PDI was carried out in the absence of oxygen but in the presence of 10 mM added azide, bacterial killing was substantially restored. The effect was less pronounced in the case of LC14 (Figs 6A, 6D, 6G, and 6J) and LC16 (Figs 6C, 6F, 6I, and 6L) where only about 1–3 logs of killing were restored by addition of azide in the absence of oxygen. However in the case of LC15 (Figs 6B, 6E, 6H, and 6K)the oxygen-independent killing was restored to as high as 5 logs (Figs 6B and 6G) by addition of azide.

Figure 6. Comparison of bacterial PDI mediated by fullerene monoadducts (10μM) and increasing fluences of UVA or white light in presence or absence of oxygen and with and without addition of 10 mM NaN3.

(A) MRSA and LC14 UVA light; (B) MRSA and LC15 UVA light; (C) MRSA and LC16 UVA light; (D) E. coli and LC14 UVA light; (E) E. coli and LC15 UVA light; (F) E. coli and LC16 UVA light; (G) MRSA and LC14 white light; (H) MRSA and LC15 white light; (I) MRSA and LC16 white light; (J) E. coli and LC14 white light; (K) E. coli and LC15 white light; (L) E. coli and LC16 white light;

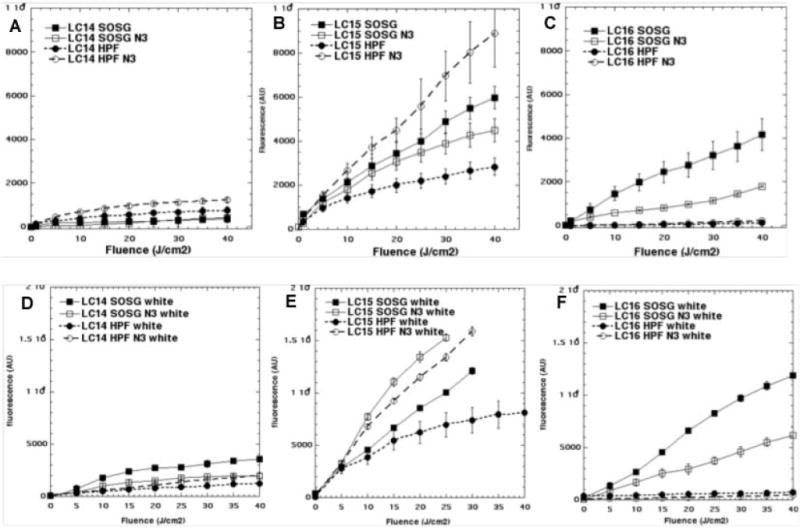

Measurement of different ROS with specific probes

We used the fluorescent probes SOSG (relatively specific for singlet oxygen) and HPF (relatively specific for hydroxyl radicals) to try and tease apart the different contributions of Type-II (singlet oxygen) and Type-I (hydroxyl radicals) photochemical pathways to the microbial photoinactivation mechanisms with different fullerene structures, different excitation wavelengths and presence or absence of azide. Activation of the probes by light alone was negligible, except for the case of SOSG and white light, where minor activation was observed, but this was less than any fullerene-mediated activation. The data are shown in Fig 7. Several observations can be easily made. Firstly the order of effectiveness between the three fullerenesfor activating both the probes with both wavelength ranges was LC15 (Figs 7B and 7E) > LC16 (Figs 7C and 7F) > LC14 (Figs 7A and 7D). Secondly there were differences between the three fullerenes in the extent to which they activated the two different probes. LC14 activated HPF more than SOSG with UVA light (Fig 7A) but activated SOSG more than HPF with white light (Fig 7D). LC15 activated both probes with both wavelengths although HPF was activated more than SOSG. LC16 activated HPF much more than SOSG with both wavelengths. Thirdly the white light excitation (Figs 7D, 7E, and 7F) was somewhat (about 50%) better at exciting both probes than the same fluence of UVA light (Figs 7A, 7B, and 7C), despite the clear superiority (5 times better) of UVA light over white light in mediating the microbial killing. This applies to all three structures and all three species. Fourthly we can make a set of observations about the effect of added azide. Azide inhibited the activation of SOSG by LC14 and white light but potentiated the activation of HPF by UVA light. For LC15 we saw a modest azide-inhibition of SOSG activation using UVA light and a strong azide-potentiation of activation of HPF using UVA light. With white light and LC15 we saw potentiation of activation of both probes (SOSG and HPF) by addition of azide. With LC16 there was azide-inhibition of activation of SOSG using both wavelengths of light (UVA and white).

Figure 7. Activation of SOSG and HPF probes (5μM) by fullerene monoadducts (5μM) excited by UVA or white light with and without 10 mM azide (N3−).

(A) LC14 and UVA light; (B) LC15 and UVA light; (C) LC16 and UVA light; (D) LC14 and white light; (E) LC15 and white light; (F) LC16 and white light;

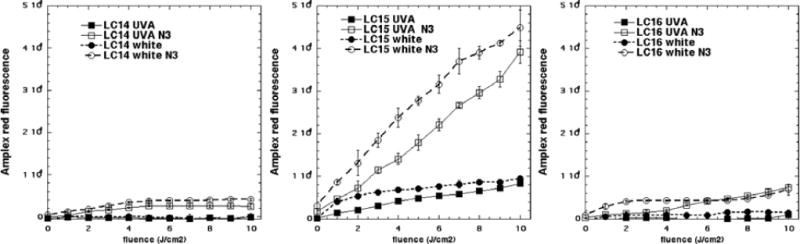

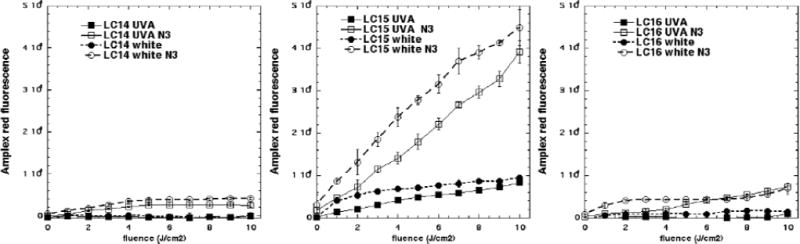

Because of the surprising observation that the activation of ROS probes was greater with white light compared to UVA while the microbial killing was much greater with UVA light compared to white light, we carried out the Amplex red assay for hydrogen peroxide, in case it turned out that H2O2 was strongly produced by UVA light compared to white, and to gain further information on precisely what reaction azide was potentiating. Figure 8 displays the data. Firstly it can be seen that in a similar manner to ROS probes that the amount of Amplex red activation was a little higher with white light compared to UVA light especially for LC15 (Fig 8B). Secondly the order of effectiveness in producing H2O2 was LC15 ≫ LC14 and LC16. Thirdly azide strongly potentiated the production of H2O2 by both wavelengths of light especially by LC15 but also by both other fullerenes.

Figure 8. Activation of Amplex red assay by hydrogen peroxide produced by excitation of fullerene monoadducts (5μM) by UVA or white light with and without 10 mM azide.

(A) LC14; (B) LC15;(C) LC16.

We also carried out the nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) assay for superoxide production. Here we were able to show that white light activated NBT more than UVA in the case of LC15 and LC16. We could not detect NBT activation in the case of LC14. Furthermore we could not explore the effect of adding azide on NBT activation, as azide anion appeared to react with NBT in the dark to produce a blue color.

Discussion

We have previously reported on the PDT activity of various fullerenes functionalized by decacationic chains [36]. The general rationale for this synthetic modification was based on four different hypotheses. Firstly, the ten quaternary ammonium groups should provide water solubility to the insoluble fullerene cage and inhibit the tendency of the hydrophobic fullerene cages to aggregate. Secondly, the pronounced overall cationic charge provided by these ten quaternary centers was expected to give broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity. It is known that for Gram-positive bacteria cationic charge is not particularly necessary for high PDI activity, but for the Gram-negative bacteria that have a strong permeability barrier against neutral and anionic molecules, cationic charges are critically important. It has been shown that increasing the number of cationic charges present on the PS molecule proportionately increases the ability to mediate photodestruction of the Gram-negative species such as E.coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [37, 38]. Thirdly, it was hypothesized that the cationic charges would increase the selectivity for microbial cells over host mammalian cells, because cationic molecules are taken up only slowly by mammalian cells but bind rapidly to microbial cells. Fourthly, the ten iodide counter ions present on the decacationic chains could act as an additional source of electrons and increase photo-induced electron transfer mechanisms and potentiate Type-I photochemistry such as hydroxyl radical generation.

The rationale behind the addition of the fluorene-triphenylamine moiety called a “light harvesting antenna” in LC15 was as follows. Extending the light absorption further into the visible range (red-shifting) should widen the range of activation of the fullerene for medical purposes as UV light (even the relatively harmless UVA wavelengths) can be considered undesirable due to poor penetration into tissue and possible harmful effects on host cells. Moreover there was a possibility that the electron donating ability of the tertiary amine in the triphenylamine could act also as an electron donor increasing electron transport both intramolecularly and intermolecularly.

The rationale behind the addition of the second chain of ten tertiary amines to LC16 was as follows. We previously showed that addition of a similar deca-tertiary amine chain to either a decacationic C70 fullerene monoadduct [39] or to a decacationic C84O2 fullerene monoadduct [40] potentiated the PDT activity both against cancer cells and against microbial cells. Furthermore the presence of the deca-tertiary amine chain increased contribution of Type-I photochemistry to the PDT effect as demonstrated by increased activation of the hydroxyl radical probe HPF. Interestingly this effect was more pronounced after UVA excitation that after white light excitation.

In the present report some of these hypotheses were validated by the results obtained and some were not. We eventually concluded that the photochemical mechanism (energy transfer or electron transfer) is of major importance in explaining the results. In the presence of oxygen it is difficult to be one hundred percent sure about which of these pathways is dominant as the relative microbicidal effects of singlet oxygen and hydroxyl radicals are still uncertain. The potentiation of bacterial killing with the addition of azide(N3−) is however a good indication of the occurrence of electron transfer reactions as opposed to energy transfer reactions as azide is a well-known quencher of singlet oxygen and has been shown to inhibit bacterial PDT killing by traditional tetrapyrrole photosensitizers [41]. In a previous study we compared the fluorescent probe activation (SOSG and HPF) and the aPDI mediated by a triscationic fullerene adduct with that mediated by a cationic polyethylenimine chlorin e6 conjugate [42]. In that study we attributed the potentiation of HPF activation by azide, and the poor inhibition of bacterial killing when azide anion was added, to the generation of hydroxyl radicals from the photoactivated fullerene cage in the presence of oxygen presumably via superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide. The hypothesis was that hydroxyl radicals could accept an electron from azide anion to produce hydroxide anions and azidyl radicals. The azidyl radicals could possibly react with HPF to activate the fluorescence by releasing fluorescein, and moreover these azidyl radicals could produce more bacterial killing than was found with hydroxyl radicals because their lower reactivity could allow them to penetrate further into the bacterial cell than the extremely reactive hydroxyl radicals which may all be used up at the outer cell wall.

However in light of the present results we have been forced to change our hypothesis somewhat. Now it appears that the photoactivated fullerene cage directly accepts an electron transferred from azide anion to produce azidyl radicals and fullerenyl radical anions. The azidyl radicals are still presumed to be able to mediate bacterial killing especially in the absence of oxygen. The role of the increased yield of fullerene radical anions remains uncertain. It is likely that the increased yield of Type-I ROS (HO·, H2O2 and O2−·) in the presence of azide is because of the facilitated production of fullerenyl radical anions. However it appears that another microbicidal species must be formed as all the Type-I ROS measured were greater with white light, while the actual killing was much higher with UVA light. Therefore we propose another possibility that the fullerene radical anions could pass their unpaired electrons into the respiratory chain of the bacteria producing an internal cytotoxic effect, and at the same time regenerating ground state fullerenes that can take part in a new electron transfer reaction.

The compound LC15 was originally synthesized to take advantage of the light harvesting antennae to red-shift the absorption spectrum into the visible region. This was partly found to be the case as LC15 consistently gave relatively more killing with 5X white light than with 1X UVA light, while both LC14 and LC16 gave more killing with 1X UVA light than with 5X white light (except LC16 and Candida). However, it now appears that LC15 markedly increases the likelihood of electron transfer reactions taking place as shown by the fact that there is potentiation of both MRSA and E. coli killing by azideanions in the presence of oxygen when excited by UVA light that was not seen with either LC14 or with LC16. Moreover there was relatively greater bacterial killing by LC15 in the presence of azideanions and the absence of oxygen, than was seen for either LC14 or for LC16.

We hypothesized that the additional chain of ten tertiary amines (electron donating groups) in LC16 would also act as a source of electrons to encourage electron transfer reactions upon photoexcitation. A similar finding was reported with a pair of analogous C70 fullerene derivatives and also a pair of C84O2 fullerene derivatives [40]. In that study the target of the PDT was cancer cells rather than bacteria. It was found that shorter wavelength and the presence of the deca-tertiary amine chain both tended to encourage electron transfer reactions and activation of HPF. Moreover the antioxidant ascorbic acid could act as a pro-oxidant at low concentrations (around 10 μM) but at higher concentrations (> 50 μM), it acted as a ROS quencher. We hypothesized that a one electron transfer from ascorbate could produce ascorbate radicals at low ascorbate concentrations. In the present case LC16 appeared to act via a Type-II mechanism (SOSG ≫ HPF) with regard to probe activation, but could clearly undergo electron transfer reactions as there was bacterial killing in the presence of azide and absence of oxygen. Moreover LC16 was the most active compound overall despite producing less ROS than LC15. LC14 was the least active fullerene overall both in the production of ROS and also in the killing of microbial cells, but did give killing in the presence of azideanions and absence of oxygen.

We recently published a paper describing the paradoxical potentiation by addition of azide anions of antimicrobial PDI mediated by the phenothiazinium salt, methylene blue (MB) [31]. This finding prompted us to test whether MB could still mediate bacterial killing in the absence of oxygen when azide anions were added. This was found to be the case although it was somewhat difficult to design the experiments as we also found that the MB photosensitizer was chemically reduced to a colorless form (leuko-MB) by the bacterial cells in the absence of oxygen. This loss of color did not occur in the presence of oxygen presumably because the respiratory enzymes in the bacteria prefer to use oxygen and only use MB when oxygen is unavailable.

Taking together the data obtained with MB as PS [31], and the data from fullerenes as PS in the present study we have formulated the proposed mechanisms of PDT as follows. Firstly, there is an initial excitation of the PS to the triplet state (eq 1) that can react in two ways: the well known energy transfer from triplet PS to ground state triplet oxygen to produce the excited state singlet oxygen (eq 2); or alternatively the excited singlet or triplet PS could accept an electron from some electron donor to produce the PS radical anion (eq 3). The PS radical anion could then carry out a one electron reduction of ground state oxygen to produce superoxide (eq 4). Superoxide can form hydrogen peroxide by the process of dismutation (either spontaneous or enzyme catalyzed) to form hydrogen peroxide (eq 5). Finally, the PS radical anion can carry out a one-electron reduction of hydrogen peroxide to form hydroxide anion and hydroxyl radical (eq 6). HO•, H2O2 and O2•−

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

The hydroxyl radical can easily react with biomolecules in microbial cells causing cell death. We originally proposed [42] that the hydroxyl radicals could react with azide anions to carry out a one-electron transfer reaction to give hydroxide anions and azidyl radicals (eq 7)

| (7) |

However it was interesting in that study to observe that the azidyl radical spin product was still formed in the absence of oxygen [31]. This finding prompted us to test whether azide anion could potentiate bacterial killing by photoactivated fullerenes in absence of oxygen. The present data show that for LC15 in particular that has a high propensity for electron transfer reactions, good killing was obtained in the absence of oxygen when azide anions was added. Azide anions also gave PDI killing to a lesser extent in the cases of LC16 and LC14 in the absence of oxygen. In the light of these data we revised our basic hypothesis of the mechanism to the following shown in eq 8.

| (8) |

Although we originally hypothesized that the azidyl radicals could activate the HPF fluorescent probe in the presence of oxygen there is no hard evidence for this. The fact that azide anions allow the photoactivated fullerenes to kill the bacteria in the absence of oxygen does suggest that azidyl radicals can be cytotoxic. It would have been a good idea to test whether addition of azide could have given activation of HPF probe by photoactivated fullerenes in the absence of oxygen. This would be predicted if azidyl radicals are responsible for increased probe activation in the presence of oxygen. Unfortunately this experiment is technically difficult at present as probe activation experiments are carried out in 96-well plates and we are unable to remove oxygen from 96-well plates while at the same time photoactivating them with white light and reading fluorescence in a plate reader. In our opinion the explanation for the greater generation of Type-I ROS (HO·, H2O2 and O2−·) in the presence of azide is the increased production of fullerene radical anions by electron transfer from azide anion.

One perplexing question that needs to be addressed is the difference between the relative effectiveness of UVA and white light in activating the various probes for different ROS, taken together with the relative effectiveness of UVA and white light in killing the microbial cells. This is especially puzzling when the data in Table 1 are considered, which show that between 1.8 and 3 times as many white photonsare absorbed by the fullerenes compared to UVA photons absorbed, depending on precise structure. We consistently found that UVA fluences were comparable (and often even less effective) than white light fluences for activating SOSG and HPF, which is consistent with the relative numbers of photons absorbed (Table 1). Since we consistently found that we needed about five times as much white light in J/cm2 to give the same microbial killing as was achieved when the fullerenes were excited with one fifth the fluence of UVA light, we must search for an explanation for this disparity. This difference was not due to any microbicidal effect of UVA light alone as can be seen from Fig 4. We considered whether ROSthat were different from HO· and 1O2 (such as superoxide or hydrogen peroxide) could be (partly) responsible for microbial killing, and which in principle could be preferentially generated by UVA excitation. Therefore, we used the Amplex Red assay for hydrogen peroxide and the NBT assay for superoxide anion. The data shown in Figs 7 and 8 actually show that the reverse was true, and this finding was rather in agreement with the SOSG and HPF data. If anything more O2−· and H2O2 were produced by white light than were produced by UVA light. LC15 with the greatest tendency to carry out Type-I electron transfer reactions did give more O2−· and H2O2 than the other fullerenes thus confirming our previous results.

We have therefore developed a new hypothesis to explain all of these observations that involves postulating a new method of bacterial cell death following PDI. We propose a mechanism involving the direct “pumping” of electrons into the bacteria from photoexcited fullerenes especially when excited with high energy UVA light, and especially in the presence of electron donors such as azide anion. It is worth mentioning that by analogy with the antimicrobial mechanism described by Kohanskiet al [43] that this mechanism would involve the internal generation of ROS inside the bacterial cells by a Fenton reaction catalyzed by ferrous iron released from disrupted iron-sulfur clusters. This being the case it would not be expected to operate effectively in the absence of oxygen, as in that case no ROS could be generated. The lower ability of white light-excited fullerenes to carry out this electron transfer killing is presumably explained by the hypothesis that lower energy “white” photons are less likely to drive this “electron pumping effect”. A number of additional experiments are underway in our laboratory to gather hard evidence for or against this new proposed mechanism of antimicrobial photoinactivation, and will be reported in due course.

It must be mentioned that azide anion has considerable toxicity to mammalian cells although not so much towards microbial cells. Therefore, it would not be possible to use azide anion in a clinical potentiation of antimicrobial PDT to treat an infection. However, it may be possible to find a different non-toxic small molecule electron donor that can perform as well (or even better) than azide anion, and we are actively testing several possibilities.

Supplementary Material

Figure 9. Reduction of NBT by superoxide produced by excitation of fullerene monoadducts (5μM) by UVA or white light.

(A) LC14; (B) LC15;(C) LC16.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by US NIH grantsR01CA137108 and R01AI050875. The authors at UML also acknowledge support by AFOSR grants FA9550-09-1-0183 and FA9550-09-1-0380. Rui Yin was supported by Chinese National Natural Science Foundation (Grant No: 81172495).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kraus CN. Low hanging fruit in infectious disease drug development. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11:434–438. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoneyama H, Katsumata R. Antibiotic resistance in bacteria and its future for novel antibiotic development. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2006;70:1060–1075. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamblin MR, Hasan T. Photodynamic therapy: a new antimicrobial approach to infectious disease? Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2004;3:436–450. doi: 10.1039/b311900a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maisch T. Anti–microbial photodynamic therapy: useful in the future? Lasers in medical science. 2007;22:83–91. doi: 10.1007/s10103-006-0409-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maisch T, Hackbarth S, Regensburger J, Felgentrager A, Baumler W, Landthaler M, Roder B. Photodynamic inactivation of multi-resistant bacteria (PIB) - a new approach to treat superficial infections in the 21st century. Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft = Journal of the German Society of Dermatology: JDDG. 2011;9:360–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2010.07577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bush K, Courvalin P, Dantas G, Davies J, Eisenstein B, Huovinen P, Jacoby GA, Kishony R, Kreiswirth BN, Kutter E, Lerner SA, Levy S, Lewis K, Lomovskaya O, Miller JH, Mobashery S, Piddock LJ, Projan S, Thomas CM, Tomasz A, Tulkens PM, Walsh TR, Watson JD, Witkowski J, Witte W, Wright G, Yeh P, Zgurskaya HI. Tackling antibiotic resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:894–896. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almeida RD, Manadas BJ, Carvalho AP, Duarte CB. Intracellular signaling mechanisms in photodynamic therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1704:59–86. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jori G, Brown SB. Photosensitized inactivation of microorganisms. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2004;3:403–405. doi: 10.1039/b311904c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soncin M, Fabris C, Busetti A, Dei D, Nistri D, Roncucci G, Jori G. Approaches to selectivity in the Zn(II)-phthalocyanine-photosensitized inactivation of wild-type and antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2002;1:815–819. doi: 10.1039/b206554a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lauro FM, Pretto P, Covolo L, Jori G, Bertoloni G. Photoinactivation of bacterial strains involved in periodontal diseases sensitized by porphycene-polylysine conjugates. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2002;1:468–470. doi: 10.1039/b200977c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang L, Terakawa M, Zhiyentayev T, Huang YY, Sawayama Y, Jahnke A, Tegos GP, Wharton T, Hamblin MR. Innovative cationic fullerenes as broad-spectrum light-activated antimicrobials. Nanomedicine: nanotechnology, biology, and medicine. 2010;6:442–452. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma SK, Chiang LY, Hamblin MR. Photodynamic therapy with fullerenes in vivo: reality or a dream? Nanomedicine (Lond) 2011;6:1813–1825. doi: 10.2217/nnm.11.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang M, Huang L, Sharma SK, Jeon S, Thota S, Sperandio FF, Nayka S, Chang J, Hamblin MR, Chiang LY. Synthesis and photodynamic effect of new highly photostable decacationically armed [60]- and [70]fullerene decaiodide monoadducts to target pathogenic bacteria and cancer cells. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2012;55:4274–4285. doi: 10.1021/jm3000664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang M, Maragani S, Huang L, Jeon S, Canteenwala T, Hamblin MR, Chiang LY. Synthesis of decacationic [60]fullerene decaiodides giving photoinduced production of superoxide radicals and effective PDT–mediation on antimicrobial photoinactivation. European journal of medicinal chemistry. 2013;63C:170–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.01.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cataldo F, DR T. Medicinal Chemistry and Pharmacological Potential of Fullerenes and Carbon Nanotubes. NY, USA: Springer Science+Business Media; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duncan LK, Jinschek JR, Vikesland PJ. C60 colloid formation in aqueous systems: effects of preparation method on size, structure, and surface charge. Environmental science & technology. 2008;42:173–178. doi: 10.1021/es071248s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang H, He Y, Li Y, Su H. Photophysical and electronic properties of five PCBM-like C60 derivatives: spectral and quantum chemical view. The journal of physical chemistry. A. 2012;116:255–262. doi: 10.1021/jp208520v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakamura E, Isobe H. Functionalized fullerenes in water. The first 10 years of their chemistry, biology, and nanoscience. Accounts of chemical research. 2003;36:807–815. doi: 10.1021/ar030027y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mroz P, Pawlak A, Satti M, Lee H, Wharton T, Gali H, Sarna T, Hamblin MR. Functionalized fullerenes mediate photodynamic killing of cancer cells: Type I versus Type II photochemical mechanism. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:711–719. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mizuno K, Zhiyentayev T, Huang L, Khalil S, Nasim F, Tegos GP, Gali H, Jahnke A, Wharton T, Hamblin MR. Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy with Functionalized Fullerenes: Quantitative Structure-activity Relationships. Journal of nanomedicine & nanotechnology. 2011;2:1–9. doi: 10.4172/2157-7439.1000109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yin R, Wang M, Huang YY, Huang HC, Avci P, Chiang LY, Hamblin MR. Photodynamic therapy with decacationic [60]fullerene monoadducts: Effect of a light absorbing electron-donor antenna and micellar formulation. Nanomedicine: nanotechnology, biology, and medicine. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Navarre WW, Schneewind O. Surface proteins of gram-positive bacteria and mechanisms of their targeting to the cell wall envelope. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews: MMBR. 1999;63:174–229. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.1.174-229.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nikaido H. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews: MMBR. 2003;67:593–656. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.593-656.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott JR, Barnett TC. Surface proteins of gram-positive bacteria and how they get there. Annual review of microbiology. 2006;60:397–423. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malik Z, Ladan H, Nitzan Y. Photodynamic inactivation of Gram-negative bacteria: problems and possible solutions. Journal of photochemistry and photobiology B, Biology. 1992;14:262–266. doi: 10.1016/1011-1344(92)85104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharma SK, Dai T, Kharkwal GB, Huang YY, Huang L, Bil De, Arce VJ, Tegos GP, Hamblin MR. Drug discovery of antimicrobial photosensitizers using animal models. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:1303–1319. doi: 10.2174/138161211795703735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guldi DM, Prato M. Excited-state properties of C(60) fullerene derivatives. Accounts of chemical research. 2000;33:695–703. doi: 10.1021/ar990144m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bingel C. Cyclopropylation of fullerenes. Chem Ber. 1993;126:1957–1959. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dai T, Bil de Arce VJ, Tegos GP, Hamblin MR. Blue dye and red light, a dynamic combination for prophylaxis and treatment of cutaneous Candida albicans infections in mice. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2011;55:5710–5717. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05404-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jett BD, Hatter KL, Huycke MM, Gilmore MS. Simplified agar plate method for quantifying viable bacteria. Biotechniques. 1997;23:648–650. doi: 10.2144/97234bm22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang L, St Denis TG, Xuan Y, Huang YY, Tanaka M, Zadlo A, Sarna T, Hamblin MR. Paradoxical potentiation of methylene blue–mediated antimicrobial photodynamic inactivation by sodium azide: role of ambient oxygen and azide radicals. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53:2062–2071. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Setsukinai K, Urano Y, Kakinuma K, Majima HJ, Nagano T. Development of novel fluorescence probes that can reliably detect reactive oxygen species and distinguish specific species. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:3170–3175. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209264200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flors C, Fryer MJ, Waring J, Reeder B, Bechtold U, Mullineaux PM, Nonell S, Wilson MT, Baker NR. Imaging the production of singlet oxygen in vivo using a new fluorescent sensor, Singlet Oxygen Sensor Green. Journal of experimental botany. 2006;57:1725–1734. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Driever SM, Fryer MJ, Mullineaux PM, Baker NR. Imaging of reactive oxygen species in vivo. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;479:109–116. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-289-2_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maccarrone M, Rossi A, D’Andrea G, Amicosante G, Avigliano L. Electrophoretic detection of ascorbate oxidase activity by photoreduction of nitroblue tetrazolium. Analytical biochemistry. 1990;188:101–104. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90534-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sperandio FF, Gupta A, Wang M, Chandran R, Sadasivam M, Huang YY, Chiang LY, Hamblin MR. Photodynamic Therapy Mediated by Fullerenes and their Derivatives. New York, NY: American Society of Mechanical Engineers/Momentum Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mesquita MQ, Menezes JC, Neves MG, Tome AC, Cavaleiro JA, Cunha A, Almeida A, Hackbarth S, Roder B, Faustino MA. Photodynamic inactivation of bioluminescent Escherichia coli by neutral and cationic pyrrolidine-fused chlorins and isobacteriochlorins. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters. 2014;24:808–812. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.12.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spesia MB, Lazzeri D, Pascual L, Rovera M, Durantini EN. Photoinactivation of Escherichia coli using porphyrin derivatives with different number of cationic charges. FEMS immunology and medical microbiology. 2005;44:289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.femsim.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang L, Wang M, Sharma SK, Sperandio FF, Maragani S, Nayka S, Chang J, Hamblin MR, Chiang LY. Decacationic [70]Fullerene Approach for Efficient Photokilling of Infectious Bacteria and Cancer Cells. ECS Trans. 2013;45 doi: 10.1149/04520.0065ecst. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sperandio FF, Sharma SK, Wang M, Jeon S, Huang YY, Dai T, Nayka S, de Sousa SC, Chiang LY, Hamblin MR. Photoinduced electron-transfer mechanisms for radical-enhanced photodynamic therapy mediated by water-soluble decacationic C(7)(0) and C(8)(4)O(2) Fullerene Derivatives. Nanomedicine: nanotechnology, biology, and medicine. 2013;9:570–579. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spesia MB, Durantini EN. Photodynamic inactivation mechanism of Streptococcus mitis sensitized by zinc(II) 2,9,16,23-tetrakis[2-(N,N,N-trimethylamino)ethoxy]phthalocyanine. Journal of photochemistry and photobiology B, Biology. 2013;125:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang L, Xuan Y, Koide Y, Zhiyentayev T, Tanaka M, Hamblin MR. Type I and Type II mechanisms of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy: An in vitro study on gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. Lasers Surg Med. 2012;44:490–499. doi: 10.1002/lsm.22045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, Hayete B, Lawrence CA, Collins JJ. A common mechanism of cellular death induced by bactericidal antibiotics. Cell. 2007;130:797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.