Abstract

The objective of the present study was to develop a discriminatory and reproducible accelerated in vitro release method for long-acting PLGA microspheres with inner structure/porosity differences. Risperidone was chosen as a model drug. Qualitatively and quantitatively equivalent PLGA microspheres with different inner structure/porosity were obtained using different manufacturing processes. Physicochemical properties as well as degradation profiles of the prepared microspheres were investigated. Furthermore, in vitro release testing of the prepared risperidone microspheres was performed using the most common in vitro release methods (i.e. sample-and-separate and flow through) for this type of product. The obtained compositionally equivalent risperidone microspheres had similar drug loading but different inner structure/porosity. When microsphere particle size appeared similar, porous risperidone microspheres showed faster microsphere degradation and drug release compared with less porous microspheres. Both in vitro release methods investigated were able to differentiate risperidone microsphere formulations with differences in porosity under real-time (37°C) and accelerated (45°C) testing conditions. Notably, only the accelerated USP apparatus 4 method showed good reproducibility for highly porous risperidone microspheres. These results indicated that the accelerated USP apparatus 4 method is an appropriate fast quality control tool for long-acting PLGA microspheres (even with porous structures).

Keywords: PLGA microspheres, Porous, Compositionally equivalent, Accelerated in vitro release, Risperidone, USP apparatus 4

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, complex parenteral microsphere drug products have been successfully utilized to deliver a variety of therapeutics (small molecules as well as proteins/peptides) in a controlled manner over periods of weeks to months (Mao et al., 2012; Sinha and Trehan, 2003; Wang and Burgess, 2012). The majority of these microsphere drug products (such as Risperdal® Consta®, Lupron Depot®, as well as Sandostatin® LAR) are composed of poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) and/or poly(lactic acid) (PLA) polymers owing to their excellent biodegradability and biocompatibility. While these microsphere drug products are invaluable for improving patient compliance and satisfying therapeutic needs, they normally contain substantial amounts of potent therapeutic agents and therefore, any unanticipated changes in their in vivo drug release characteristics may lead to severe side effects and impaired in vivo efficacy. Furthermore, these microspheres products have complex formulations and complicated processing methodologies. Manufacturing changes (e.g. change in the manufacturing site and instrumentation) have the potential to affect microsphere physicochemical characteristics, which in turn may affect their in vitro and in vivo performance. Accordingly, it is critical to ensure the in vivo performance and safety of these drug products.

In vitro release testing methods with good discriminatory ability and reproducibility are critical for quality control purposes, as well as to assist in product development. For long-acting PLGA microspheres, real-time release testing requires extended periods of time, which would significantly affect the time for batch release of product and hence negatively impact product shelf-life (Burgess et al., 2004; Martinez et al., 2010). Accordingly, accelerated in vitro release methods of PLGA microspheres which can correlate with real-time in vitro release are essential. It has been reported that several factors (e.g. temperature, pH, surfactants, and the presence of enzymes) can hasten the rate of polymer hydration and/or polymer degradation and drug diffusion, thus accelerating drug release from PLGA microspheres (Alexis, 2005; Shen and Burgess, 2012b; Zolnik and Burgess, 2007; Zolnik et al., 2006). Ideally, drug release in real-time and accelerated tests should follow the same release mechanism with a 1:1 correlation between the release profiles (Zolnik et al., 2006). However, it is possible that the drug release mechanism(s) may change since accelerated release tests are typically performed under extreme conditions (e.g. high temperatures, and extreme pH conditions). Nevertheless, real-time and accelerated release profiles should show a minimum of a rank order relationship between different formulations (Burgess et al., 2004).

At present, there is a lack of compendial in vitro release methods for microsphere dosage forms. Various in vitro release testing methods (such as sample-and-separate, membrane dialysis and continuous flow) have been widely used for in vitro release testing of PLGA microspheres (Chu et al., 2006; D’Souza and DeLuca, 2006; Rawat and Burgess, 2011; Zolnik et al., 2005). Although the sample-and-separate method provides a direct and reasonably accurate assessment of in vitro drug release, there are limitations associated with this method. For example, inadequate agitation that may result in microsphere aggregation during long-term in vitro release testing, as well as loss of the dosage form during sampling. In case of the membrane dialysis methods, violation of sink conditions often occurs when the drug is poorly soluble in the release media as very limited media volume is available inside the dialysis sacs. In addition, lack of agitation inside the dialysis sacs may result in poor reproducibility of release data. Another potential issue is that a suitable membrane with adequate pore size and no undesirable interaction with the drug must be identified prior to release testing. Dissolution tests using USP apparatus 4 with well-defined geometry and hydrodynamics have been demonstrated to be an appropriate in vitro release testing method for polymeric microspheres as it can not only minimize microsphere aggregation but also avoid microsphere loss during sampling (Zolnik et al., 2005).

Since physicochemical characteristics of the microspheres are sensitive to the manufacturing processes, it is critical to develop a reproducible accelerated in vitro release method to provide fast quality assessment for PLGA microspheres that are equivalent in formulation composition and components but prepared with different manufacturing processes. In the present study, risperidone (the active pharmaceutical ingredient in the commercial microsphere product Risperdal® Consta®), was chosen as a model drug. Compositionally equivalent PLGA microspheres were prepared using different manufacturing methods. Real-time and accelerated release profiles of the prepared PLGA microspheres obtained using different release testing methods (i.e. sample-and-separate, and flow through) were compared. Moreover, the discriminatory ability and the reproducibility of the accelerated in vitro release methods were investigated.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

PLGA (7525 DLG 6E) was purchased from Evonik (Birmingham, AL). Risperidone was purchased from Jai Radhe, India. Poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA, MW 30–70 kDa) and trifuoroacetic acid (TFA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Methylene chloride and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, ACS grade) were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Nanopure™ quality water (Barnstead, Dubuque, IA) was used for all studies. All other chemicals were obtained commercially as analytical-grade reagents.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Preparation of PLGA microspheres

PLGA (7525 DLG 6E) with similar molecular weight as that of the PLGA used in the commercial product Risperdal® Consta® was used to prepare compositionally equivalent risperidone microspheres using different manufacturing processes (e.g. homogenization, vortex mixing, and different solvents). Briefly, both PLGA and risperidone were dissolved in methylene chloride (DCM) (polymer/drug, 4/3 (w/w)). The polymer/drug solution was then dispersed into an aqueous PVA solution (1%, w/v) saturated with DCM to form an oil-in-water (o/w) emulsion via homogenization (3,400 rpm, 2 minutes) (IKA® Works, Inc.). The microparticles were hardened via solvent extraction at room temperature for 3 hours and the solvent was then removed under vacuum. The resulting microspheres were washed using distilled water and sieved using 25 μm and 212 μm sieves and lyophilized. To obtain porous PLGA microspheres, PLGA was dissolved in ethyl acetate (EA, 16.7%, w/w) and risperidone was dissolved in benzyl alcohol (BA, 24%, w/w). The polymer and the drug solution were mixed and transferred to the 1% (w/v) PVA solution (saturated with EA) to form oil-in-water (o/w) emulsions via either vortex mixing (1,200 rpm, 10 seconds) or homogenization (3,400 rpm, 30 seconds). The resultant emulsions were transferred to a solvent extraction medium (2.5% (v/v) EA in water) and the solvent was extracted overnight at 4°C. Following solvent extraction, any remaining organic solvent was removed under vacuum at room temperature. The microspheres were then collected, washed using an aqueous ethanol solution (25%, v/v), sieved using 25 μm and 212 μm sieves and lyophilized. Blank PLGA microspheres were prepared using the procedures described above without the addition of the drug.

2.2.2. High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis

The quantification of risperidone was conducted using a Perkin Elmer HPLC system (series 200) with a UV absorbance detector (Perkin Elmer, Shelton, CT) set at 275 nm. The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile/water/TFA (30/70/0.1, v/v/v). A Kinetex C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm, 100 Å) was used with a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The chromatographs were analyzed using a PeakSimple™ Chromatography System (SRI instruments, Torrance, CA). This method is a stability indicating HPLC assay (Rawat et al., 2011). Injection volumes of 10 μl and 50 μl were used for determination of drug loading and drug release samples, respectively.

2.2.3. Drug loading

Five mg of the risperidone microspheres were weighed and transferred into a 10 mL volumetric flask. DMSO (2.5 mL) was added into the volumetric flask and the samples were sonicated until all particles were dissolved. Methanol was used to dilute the sample. The solution was filtered (Millex® HV, 0.22 μm PVDF syringe filter) and the risperidone concentration was determined via HPLC. Drug loading was determined as: percent drug loading = (weight of drug entrapped/weight of microspheres used) × 100.

2.2.4. Particle size and particle size distribution

Particle size and particle size distribution of the risperidone microspheres were measured using an AccuSizer autodiluter particle sizing system (Nicomp, Santa Barbara, CA). Briefly, microspheres were dispersed in 0.1% (w/v) PVA solution in water to ensure good dispersion and then particle size analysis was conducted.

2.2.5. Differential scanning calorimeter (DSC) analysis

The glass transition temperature (Tg) of the risperidone microspheres, as well as a physical mixture of the blank microspheres and risperidone was analyzed using a modulated temperature differential scanning calorimeter (MTDSC) (TA instrument Q2000). Briefly, experiments were performed in hermetically sealed pans using 2°C/min heating rate and a modulation amplitude of ±0.82°C with an 80 s modulation period. The weight of each sample was around 4 mg. The Tg was determined as the glass transition midpoint in the reversing signal.

2.2.6. Porosity

The porosity of the risperidone microspheres was determined using a Mercury Porosimeter (AutoPore IV 9500, Micromeritics). Briefly, approximately 200 mg of risperidone microspheres were introduced into the porosimeter and tested at a mercury filling pressure of 0.53 psi. Total intrusion volume, total pore area as well as porosity (%) were recorded (porosity (%) = bulk density / apparent (skeletal) density × 100).

2.2.7. Morphology

The morphology of the prepared risperidone microspheres was characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Briefly, dry microspheres were mounted on carbon taped aluminum stubs and sputter coated with gold. The samples were analyzed using SEM (NanoSEM 450, Nova).

2.2.8. Gel permeation chromatography (GPC)

The molecular weight of the microspheres was determined via GPC (Waters) with an evaporative light scattering detector (ELSD). The risperidone microspheres were dissolved in tetrahydrofuran (THF) and filtered through 0.45 μm filters for GPC analysis. The data collection and analysis were performed using Waters Millenium software.

2.2.9. In vitro degradation study

Around 20 mg of the risperidone microspheres were dispersed in 25 mL of 10 mM phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) with 0.01% (w/v) sodium azide and incubated in a water shaker bath (C76, New Brunswick Scientific, Edison, NJ) at 100 rpm at 37°C. At pre-determined time intervals, the microspheres were collected and washed with pure water three times and lyophilized. Samples were analyzed via SEM and gel permeation chromatography (GPC).

2.2.10. In vitro release testing

In vitro release testing of the risperidone microspheres was investigated using both sample-and-separate and USP apparatus 4 methods. In case of the sample-and-separate method, around 10 mg of microspheres were dispersed in 250 mL of 10 mM PBS (pH 7.4) and incubated in a shaker water bath at 100 rpm at either 37°C or 45°C. At predetermined time intervals, one mL samples were withdrawn and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 3 minutes. Supernatants (0.9 mL) were filtered through 0.22 μm filters and analyzed via HPLC. Fresh media (0.9 mL) were mixed with pellets (if any) and transferred back to the testing vessels. In the case of the USP apparatus 4 method, a previously developed and validated USP apparatus 4 method was used (Rawat et al., 2011). Briefly, around 10 mg of the microspheres were mixed with glass beads (1 mm) and placed in USP apparatus 4 dissolution cells. PBS (10 mM, pH 7.4) with 0.01% (w/v) sodium azide (250 mL) was circulated through the flow through cells at a flow rate of 8 mL/min at 37°C or 45°C. At pre-determined time intervals, one mL samples were withdrawn and replenished with fresh media. The release samples were analyzed via HPLC. Media replacement during the release testing was taken into account in the calculation of the fraction release. To evaluate the reproducibility of the methods, the in vitro release testing was conducted on different testing dates and by using different USP apparatus 4 systems. All drug release tests were conducted in triplicate and the results are reported as the mean±SD.

2.2.11. Statistical data analysis

Statistical analysis to evaluate significant differences between different microsphere formulations was performed using a paired student t-test. The level of significance was accepted at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical properties of risperidone microspheres

Physicochemical properties (e.g. drug loading, particle size, glass transition temperature, as well as porosity) of the prepared risperidone microspheres are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Despite that different manufacturing processes were utilized, the prepared risperidone microsphere formulations had similar drug loading (ca. 37%, w/w) (Table 1). Formulations 1 and 2 prepared using different solvent systems showed similar particle size D50 values in terms of both population (ca. 60 μm) and volume (ca. 100 μm) with a particle size distribution (p > 0.05). Formulation 3 had significantly smaller particle size compared to that of Formulations 1 and 2 (p < 0.05). No significant differences were observed in the Tg of the microspheres, and the physical mixture of the drug and the PLGA polymer (ca. 42°C). It can be seen in Table 2, that risperidone microspheres prepared using DCM as the solvent (i.e. Formulation 1) had lower porosity percentage (46%) compared to those microspheres prepared using EA&BA as the solvent (55% and 62% for Formulations 2 and 3, respectively).

Table 1.

Physicochemical properties of the prepared risperidone microsphere formulations (n=3).

| Sample | Solvent | Preparation Method | Drug Loading (%, w/w) | D50 (μm)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volume | Population | ||||

| Formulation_1 | DCM | Homogenization | 37.67±0.94 | 103.89±2.66 | 63.94±4.39 |

| Formulation_2 | EA&BA | Vortex | 37.33±0.60 | 104.22±4.63 | 55.19±4.63 |

| Formulation_3 | EA&BA | Homogenization | 36.45±1.23 | 74.04±7.53 | 41.63±1.35 |

Table 2.

Porosity of the prepared risperidone microsphere formulations (n=3).

| Sample | Total Intrusion Volume (ml/g) | Total Pore Area (m2/g) | Porosity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formulation_1 | 0.743±0.02 | 0.526±0.02 | 46.04±2.90 |

| Formulation_2 | 1.162±0.08 | 8.398±0.43 | 54.98±1.25 |

| Formulation_3 | 1.465±0.13 | 8.813±0.71 | 61.75±1.08 |

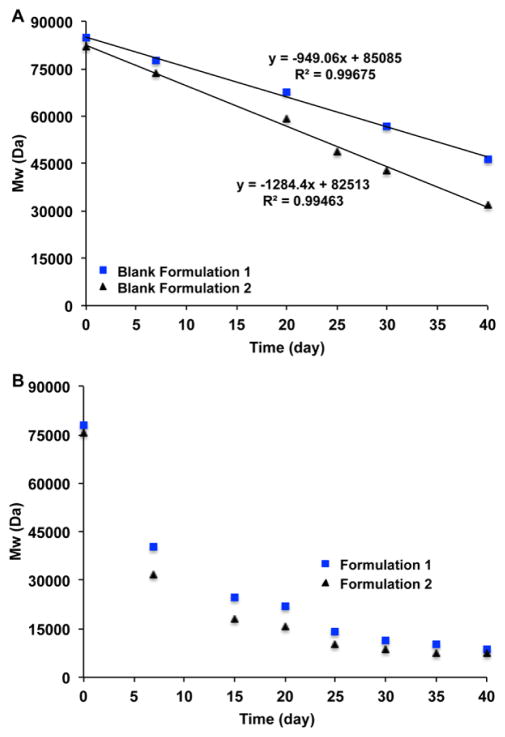

3.2. In vitro degradation of risperidone microspheres

In vitro degradation of the risperidone microspheres prepared using different solvent systems (i.e. Formulations 1 and 2) was investigated. The change in molecular weight of the PLGA microspheres during the in vitro degradation study is shown in Fig. 1. The molecular weight of less porous microspheres (i.e. Formulation 1) decreased slower compared to that of porous microspheres (i.e. Formulation 2). As shown in Fig. 1A, change in the molecular weight of blank PLGA microspheres appeared to follow pseudo-zero-order degradation with rate constants of −949 Da per day and −1284 Da per day for blank Formulations 1 and 2, respectively. However, the molecular weight of these microspheres exponentially decreased in the presence of risperidone (Fig. 1B), indicating much faster polymer degradation, which was consistent with previous literature reports (Rawat et al., 2011; Selmin et al., 2012).

Fig. 1.

Changes in molecular weight of PLGA of blank (A) and risperidone loaded PLGA microspheres (B) after exposure to 10 mM PBS (pH 7.4) at 37°C.

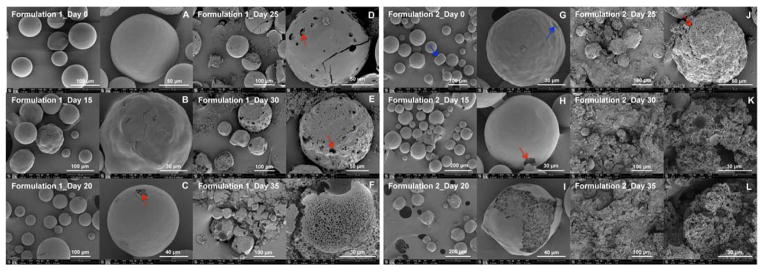

Morphological changes in the microspheres with time are shown in Fig. 2. Prior to the degradation studies, Formulation 1 appeared spherical with a relatively non-porous smooth structure (Fig. 2A), whereas some irregular shapes and indentations (shown in blue arrows) were observed for Formulation 2 (Fig. 2G), indicating a more porous structure, which was consistent with the porosity results shown in Table 2. As degradation proceeded at pH 7.4, both microsphere formulations appeared to follow the typical “inside-out” degradation mechanism. It was evident that more porous microspheres (i.e. Formulation 2) degraded faster compared with less porous microspheres (i.e. Formulation 1). In case of Formulation 1, the formation of pores and channels inside the microspheres became evident by day 20 (Fig. 2C, shown in a red arrow). Following this, polymer erosion progressed and no individual microspheres were observed by day 35 (Fig. 2F). In case of highly porous microspheres (i.e. Formulation 2), the formation of pores and channels inside the microspheres became evident by day 15 (Fig. 2H, shown in a red arrow) and polymer erosion occurred rapidly. No individual microspheres were observed by day 30 (Fig. 2K). These results indicated that even with sameness in component and composition as well as similar particle size distribution, risperidone microspheres with different porosity as a result of manufacturing differences had different degradation rates, which may result in different in vitro risperidone release characteristics.

Fig. 2.

SEM micrographs of Formulation 1 (A–F) and Formulation 2 (G–L) after exposure to 10 mM PBS (pH 7.4) over a period of 35 days. Symbol: blue arrows point to indentations on the surface of the microspheres; red arrows point to pores on the surface of the microspheres.

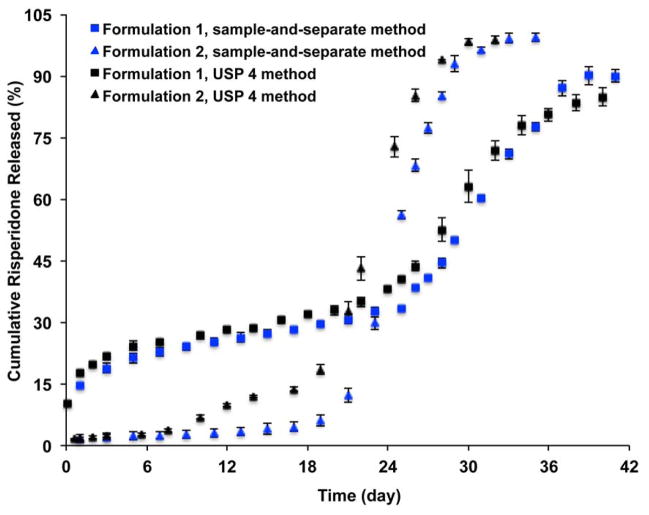

3.3. In vitro release characteristics of risperidone microspheres

Real-time in vitro release profiles of the equivalent risperidone microspheres were determined using both the sample-and-separate and USP apparatus 4 methods. As shown in Fig. 3, both in vitro release methods investigated were able to discriminate compositionally equivalent risperidone microsphere formulations with similar particle size but different inner structures/porosity (Shen et al., 2015). Formulation 1 had a higher burst release percentage (ca. 15%) followed by a longer lag-phase (up to 25 days) and reached a plateau around day 40. Formulation 2 had a lower burst release percentage (ca. 2%) and a shorter lag-phase and reached a release plateau around day 33. Furthermore, risperidone release appeared faster when the USP apparatus 4 method was used.

Fig. 3.

In vitro release profiles of the compositionally equivalent risperidone microspheres with manufacturing differences obtained using different release testing methods at 37°C in 10 mM PBS (pH 7.4) (n=3).

When in vitro release testing of the risperidone microsphere formulations was performed at an elevated temperature (45°C) using both in vitro release methods, the lag phase and risperidone release duration were significantly reduced (Fig. 4). The overall duration of risperidone release was shortened from approximately 40 days (Formulation 1) and 33 days (Formulation 2) to around 8 to 10 days at 45°C. It was noted that the USP apparatus 4 method appeared to have better discriminatory ability at elevated temperature (45°C).

Fig. 4.

In vitro release profiles of the compositionally equivalent risperidone microspheres with manufacturing differences using (A) the sample-and-separate and (B) USP apparatus 4 methods at 45°C in 10 mM PBS (pH 7.4) (n=3).

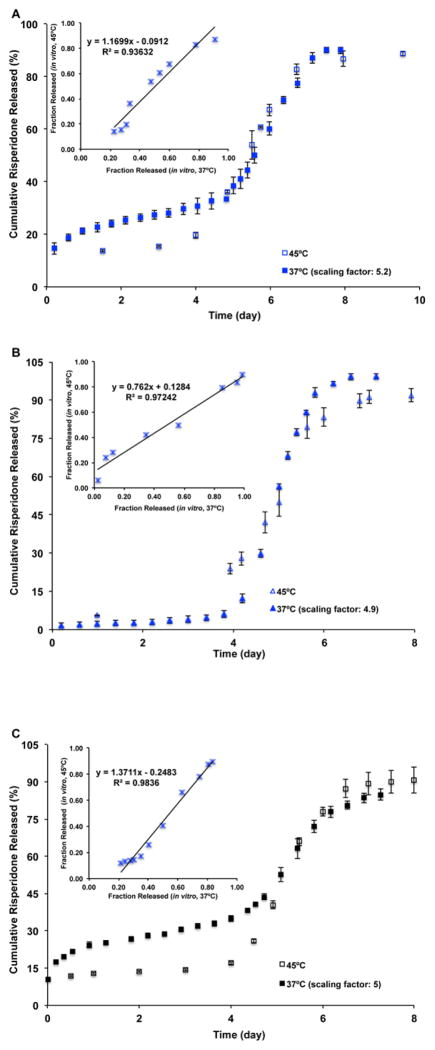

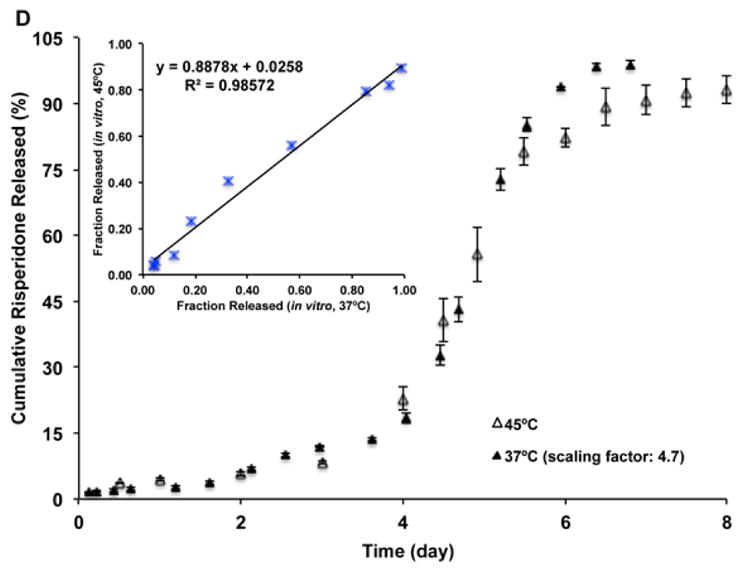

The real-time and accelerated release profiles were compared on the same axis by time scaling (scaling factor: ca. 5) the real-time release profiles (Fig. 5). In the case of Formulation 1, the fast release phase of the real-time and accelerated release profiles overlapped after time scaling. Interestingly, a small amount of risperidone release (ca. 15%) in the lag phase (over 20 days) was observed when Formulation 1 was tested at 37°C, whereas almost no risperidone release (< 5%) was observed during the lag phase (over 3 days) under accelerated conditions (45°C) (Figs. 5A and 5C). In case of Formulation 2, the real-time and accelerated release profiles of Formulation 2 appeared similar after time scaling (Figs. 5B and 5D). Better linear correlations between fraction released under real-time (time-scaled) and accelerated conditions were observed for the USP apparatus 4 method compared with the sample-and-separate method.

Fig. 5.

In vitro release profiles of the prepared risperidone microspheres in 10 mM PBS (pH 7.4) at 37°C (time-scaled) and at 45°C using different release testing methods (n=3). (A) Formulation 1 and (B) Formulation 2 using the sample-and-separate method. (C) Formulation 1 and (D) Formulation 2 using the USP apparatus 4 method. Insert figures show linear correlations between real-time (time-scaled) (37°C) and accelerated (45°C) fraction risperidone released.

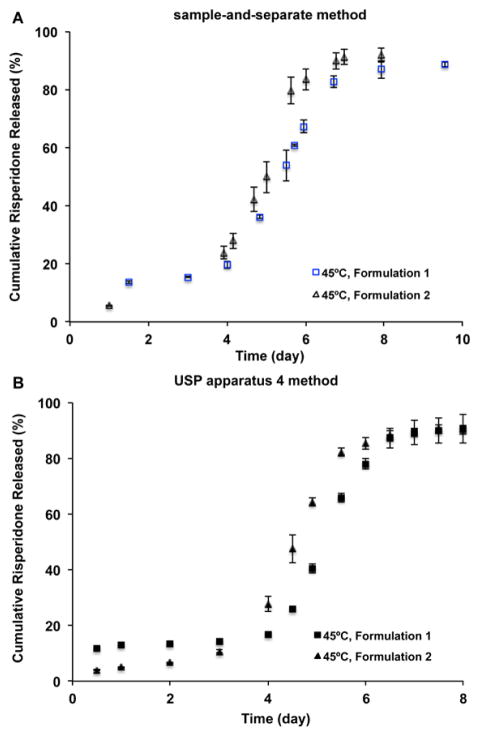

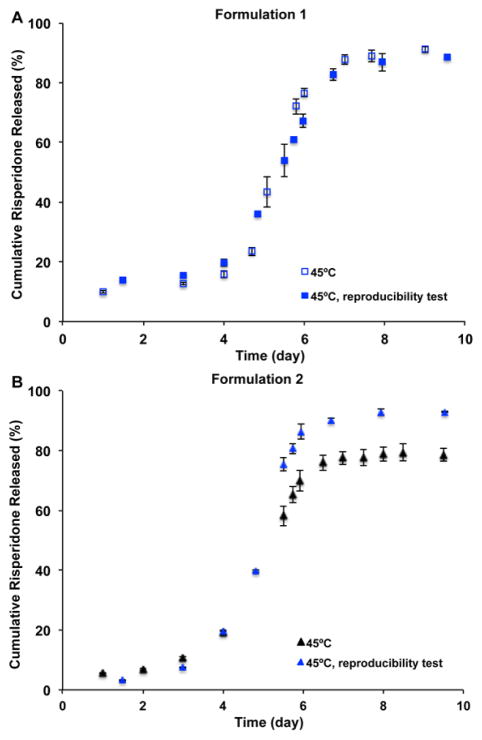

3.4. Reproducibility testing

The reproducibility of both in vitro release testing methods was investigated at elevated temperature. As shown in Fig. 6A, the accelerated in vitro risperidone release profiles of less porous microspheres (i.e. Formulation 1) appeared similar, whereas that of more porous microspheres (i.e. Formulation 2) were almost identical except that the final cumulative release percentages were different (Fig. 6B). Less than 80% final cumulative risperidone release percent was observed for one test.

Fig. 6.

In vitro release profiles of the prepared risperidone microspheres (Formulation 1 (A) and Formulation 2 (B)) in 10 mM PBS (pH 7.4) using the sample-and-separate method at 45°C (n=3).

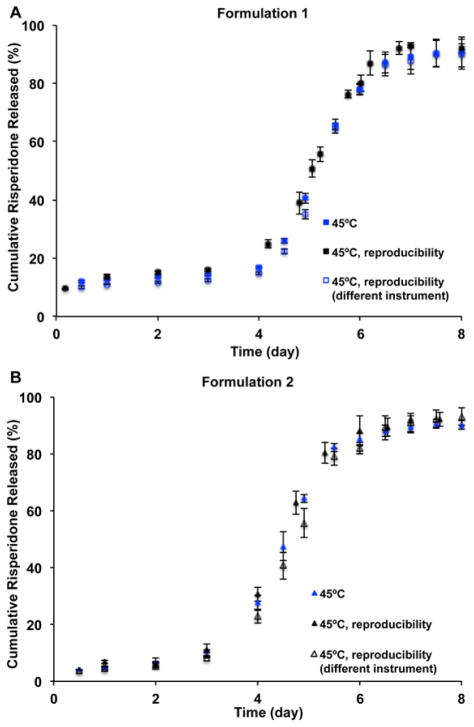

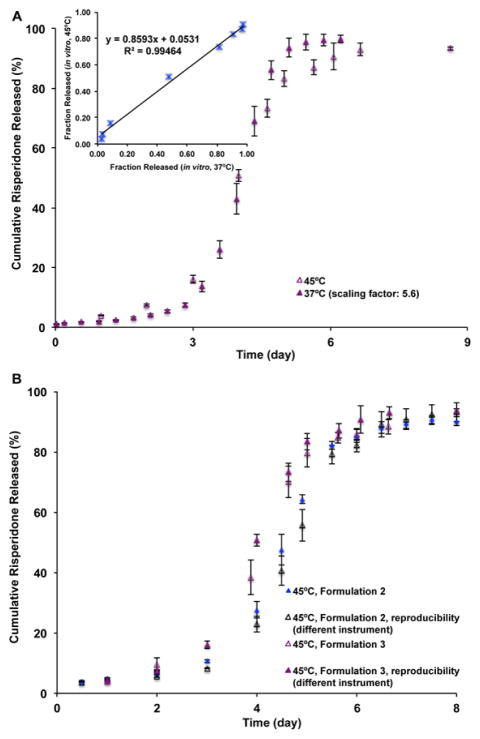

Reproducibility testing results of the USP apparatus 4 method are shown in Fig. 7. There was no significant change in the release profiles of both risperidone microsphere formulations observed even when different USP apparatus 4 systems were used, indicating that the accelerated USP apparatus 4 method was reproducible. This method was used to investigate the accelerated in vitro release characteristics of the more porous risperidone microsphere formulation (i.e. Formulation 3), which had component and composition equivalence to Formulations 1 and 2. As shown in Fig. 8A, a good linear correlation (R2 > 0.99) between the time-scaled real-time (scaling factor: 5.6) and accelerated fractions released was observed. At elevated temperature (45°C), the risperidone release reached a plateau at around 7 days. The accelerated USP apparatus 4 method was capable of discriminating the compositionally equivalent risperidone microspheres with differences in particle size and porosity (Fig. 8B). More importantly, this method demonstrated good reproducibility for in vitro release testing of porous microspheres (i.e. Formulations 2 and 3).

Fig. 7.

In vitro release profiles of the prepared risperidone microspheres (Formulation 1 (A) and Formulation 2 (B)) in 10 mM PBS (pH 7.4) using the USP apparatus 4 method at 45°C (n=3).

Fig. 8.

(A) In vitro release profiles of Formulation 3 in 10 mM PBS (pH 7.4) at 37°C (time-scaled) and at 45°C using the USP apparatus 4 method (n=3). Insert figure shows the linear correlation between real-time (time-scaled) (37°C) and accelerated (45°C) fraction risperidone released. (B) In vitro release profiles of Formulations 2 and 3 in 10 mM PBS (pH 7.4) using the USP apparatus 4 method at 45°C (n=3).

4. Discussion

It was evident that the compositionally equivalent risperidone microspheres had different physicochemical properties (e.g. particle size, and inner structure/porosity) as a result of manufacturing changes (such as solvent systems, and emulsification processes) (Tables 1 and 2). Due to solubility differences of organic solvents in water and water in organic solvents, rates of solvent movement and solvent removal during the microsphere hardening process may be different (Sah, 1997; Wischke and Schwendeman, 2008). Water has negligible solubility in DCM (0.2%, w/w) (Wischke and Schwendeman, 2008) and therefore, water diffusion into the microparticles during the microsphere hardening process was poor, resulting in less porous microspheres. In addition, since risperidone is soluble in DCM, DCM may carry a certain amount of the drug to the surface and/or outer layer of the microspheres when it is removed from the microparticles and accordingly high burst release was observed for Formulation 1 (Fig. 3). On the other hand, since EA and water are partially miscible (8.7% (w/w) EA solubility in water and 3.3% (w/w) water solubility in EA), dynamic movement of EA and water during the microsphere hardening process may result in water inclusion inside PLGA microspheres, thus generating porous microspheres following the drying process (Sah, 1997). In addition, since the polymer precipitated rapidly when in contact with water due to the relatively high water solubility of EA, drug diffusion to the surface and/or outer layer of the microspheres may be limited (Lu et al., 2014). Consequently, the drug may be mostly entrapped inside the microspheres resulting in the observed low burst release (Fig. 3). It was also observed that different emulsification processes can result in different particle size and/or inner microsphere structure (i.e. Formulations 2 and 3) when the same solvent system (i.e. EA) was used. A stronger emulsification force (homogenization vs vortex mixing) can result in smaller particles and shorter paths for water inclusion, causing higher porosity (i.e. Formulations 3).

Drug release from high molecular weight PLGA (e.g. DLG 7525 6E) microspheres is normally governed by a combination of polymer erosion and drug diffusion (Zolnik et al., 2006). Accordingly, complex drug release characteristics (e.g. bi- or tri-phasic release phase) are often observed in the release profile of these PLGA microspheres (Faisant et al., 2002). Physicochemical properties of the polymer (e.g. molecular weight, copolymer ratio and crystallinity) (Park, 1995) and the drug (Miyajima et al., 1998), as well as key quality attributes (e.g. particle size, morphology, porosity, and drug loading) of the PLGA microspheres may affect in vitro drug release characteristics (Dunne et al., 2000; Ehtezazi and Washington, 2000; Luan et al., 2006; Panyam et al., 2003). Risperidone, a tertiary amine drug with a pKa of 8.18 (20°C), has been shown to catalyze PLGA hydrolysis and degradation, thus resulting in a dramatic decrease in polymer molecular weight (Fig. 1) (Rawat et al., 2011; Selmin et al., 2012). Since the prepared risperidone microspheres were similar in composition, critical physicochemical properties of the microspheres may be mainly responsible for the different rates of microsphere degradation and drug diffusion and thereby the different in vitro release characteristics were observed. For the compositionally equivalent risperidone microspheres with similar particle size (i.e. Formulations 1 and 2), the longer lag phase and release duration of less porous microspheres (i.e. Formulation 1) may be due to a longer time period needed for polymer erosion to generate sufficient microsphere porosity to facilitate drug diffusion and subsequent release (as evidenced in Figs. 2 and 3). Smaller microspheres with a higher porosity had faster polymer degradation as well as shorter diffusional paths for the released drug to enter into the release media (Dunne et al., 2000). Accordingly, Formulation 3 showed faster risperidone release compared with Formulation 2 even though these two microsphere formulations were prepared using the same solvent system (Fig. 8B).

Accelerated in vitro release testing based on elevated temperature has been successfully used as a fast quality control tool for PLGA based parenteral dosage forms (such as microspheres and implants) (D’Souza et al., 2014; Rawat et al., 2011; Shen and Burgess, 2012a; Zolnik et al., 2006). Elevated temperature can accelerate PLGA polymer erosion (Zolnik et al., 2006), as well as enhance polymer mobility and thereby drug diffusion (Duda and Zielinski, 1996). Accordingly, significantly reduced risperidone release duration was obtained for all prepared microspheres at 45°C (Figs. 5 and 8A). Although the elevated temperature was slightly higher than the Tg (~42°C) of these microspheres, good linear correlations (R2 ~ 0.98) were observed between the time-scaled real-time and accelerated fraction released (Figs. 5 and 8A). This suggested that drug release at both temperatures may follow the same release mechanism (e.g. a combination of polymer erosion and drug diffusion). Furthermore, it has been reported that high temperature can result in the closure of pores and channels located at the microsphere surface and delay drug release (Kang and Schwendeman, 2007). Accordingly, the release of risperidone located on the surface and/or outer layer of Formulation 1 was hindered at the elevated temperature and therefore, almost no risperidone release was observed during the short lag-phase period at 45°C (Figs. 5A and 5C). However, approximately 15% of risperidone was released during the 20-day lag phase at 37°C. Notably, the accelerated release test was able to reflect the real-time burst release percent of all risperidone microsphere formulations investigated, suggesting the developed accelerated release testing method may be a good predictor for the real-time release profiles of the risperidone microspheres.

Since there is a lack of compendial in vitro release methods for complex parenteral microsphere dosage forms, various in vitro release testing methods (e.g. sample-and-separate, membrane dialysis, and continuous flow (USP apparatus 4)) have been used (D’Souza et al., 2014; Larsen et al., 2009; Rawat and Burgess, 2011; Rawat et al., 2011; Zolnik et al., 2005). Ideally, an accelerated in vitro release method based on a compendial dissolution apparatus (e.g. USP apparatus 4) is preferable as it can ensure reproducible release data and facilitate inter-laboratory comparisons. However, due to its simple apparatus setup and operation procedures as well as reduced instrumentation cost, the sample-and-separate method has been widely used for determining in vitro release characteristics of parenteral microspheres. In the present research, both the sample-and-separate and USP apparatus 4 methods showed the capability of discriminating compositionally equivalent risperidone microsphere formulations with similar particle size but different porosity under real-time and accelerated testing conditions (Figs. 3 and 4). The faster risperidone release observed in USP apparatus 4 may be due to its better hydrodynamic flow conditions. The addition of glass beads in the USP apparatus 4 dissolution cells may minimize microsphere aggregation, as well as facilitate laminar flow of release media throughout the dissolution cells (Zolnik et al., 2005 Zolnik et al., 2005), thus resulting in faster risperidone release. It has been demonstrated in another study that the sample-and-separate method using the same release medium (PBS buffer) failed to discriminate compositionally equivalent risperidone microsphere formulations with similar porosity but different particle size (unpublished results). It was considered that microsphere aggregation observed during long-term release testing may minimize the differences in particle size, thus leading to a loss of discriminatory ability of the sample-and-separate method.

When tested at elevated temperature, the sample-and-separate method showed poorer reproducibility for more porous microspheres (i.e. Formulation 2) (Fig. 6). It was observed that a large amount of Formulation 2 microspheres floated on the surface of the release media owing to their porous nature and this resulted in an inconsistent sampling process. More specifically, sample loss was observed and varied at each sampling time. Consequently, one test had less than 80% final cumulative release percentage (Fig. 6B). Considering that the addition of surfactants may facilitate wetting and minimize microsphere aggregation, 0.02% (w/v) Tween 20 was added into the release medium. However, even with the addition of Tween 20, some microspheres still floated on the surface of the release medium and therefore, the reproducibility of the sample-and-separate method for in vitro release testing of porous microspheres was not improved (data not shown). On the contrary, the USP apparatus 4 method can avoid loss during sampling and consequently, there was no inconsistent sampling process during release testing. Accordingly, the accelerated USP apparatus 4 method with well-defined geometry and hydrodynamics demonstrated excellent reproducibility for in vitro release testing of PLGA microspheres (including highly porous microspheres) even when different USP apparatus 4 systems were used (Figs. 7 and 8B).

5. Conclusions

A discriminatory and reproducible accelerated in vitro release testing method based on USP apparatus 4 is reported for the first time for compositionally equivalent PLGA microspheres with manufacturing differences. The key physicochemical attributes (e.g. particle size and porosity) that affect drug release characteristics of PLGA microspheres were shown to be sensitive to manufacturing changes. Compositionally equivalent risperidone microspheres with similar particle size but different inner structure/porosity had different microsphere degradation rates and thereby different in vitro release characteristics, which can potentially result in different in vivo risperidone release characteristics. An accelerated USP apparatus 4 method with good relevance to real-time risperidone release characteristics was capable of detecting changes in in vitro performance characteristics that resulted from changes in the manufacturing process. Most importantly, this method showed excellent reproducibility even for highly porous PLGA microspheres. These results suggest that the accelerated USP apparatus 4 method can serve as a fast quality control tool to help ensure consistent product performance and safety, as well as assist in product development of microsphere formulations.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the Office of Research and Standards, Office of Generic Drugs, CDER at the FDA (1U01FD004931-01). Support from Sotax Corporation is highly appreciated.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: This article reflects the views of the authors and should not be construed to represent FDA’s views or policies.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alexis F. Factors affecting the degradation and drug-release mechanism of poly(lactic acid) and poly[(lactic acid)-co-(glycolic acid)] Polym Int. 2005;54:36–46. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess DJ, Crommelin DJ, Hussain AS, Chen ML. Assuring quality and performance of sustained and controlled release parenterals: EUFEPS workshop report. AAPS J. 2004;6:100–111. doi: 10.1208/ps060111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu DF, Fu XQ, Liu WH, Liu K, Li YX. Pharmacokinetics and in vitro and in vivo correlation of huperzine A loaded poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) microspheres in dogs. Int J Pharm. 2006;325:116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza S, Faraj JA, Dorati R, DeLuca PP. A short term quality control tool for biodegradable microspheres. AAPS Pharm Sci Tech. 2014;15:530–541. doi: 10.1208/s12249-013-0052-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza SS, DeLuca PP. Methods to assess in vitro drug release from injectable polymeric particulate systems. Pharm Res. 2006;23:460–474. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-9397-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duda JL, Zielinski JM. Free-volume theory. In: Neogi P, editor. Diffusion in polymers. Marcel Dekker; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dunne M, Corrigan I, Ramtoola Z. Influence of particle size and dissolution conditions on the degradation properties of polylactide-co-glycolide particles. Biomaterials. 2000;21:1659–1668. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehtezazi T, Washington C. Controlled release of macromolecules from PLA microspheres: using porous structure topology. J Control Release. 2000;68:361–372. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(00)00270-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faisant N, Siepmann J, Benoit JP. PLGA-based microparticles: elucidation of mechanisms and a new, simple mathematical model quantifying drug release. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2002;15:355–366. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0987(02)00023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J, Schwendeman SP. Pore closing and opening in biodegradable polymers and their effect on the controlled release of proteins. Mol Pharm. 2007;4:104–118. doi: 10.1021/mp060041n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen C, Larsen SW, Jensen H, Yaghmur A, Ostergaard J. Role of in vitro release models in formulation development and quality control of parenteral depots. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2009;6:1283–1295. doi: 10.1517/17425240903307431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Sturek M, Park K. Microparticles produced by the hydrogel template method for sustained drug delivery. Int J Pharm. 2014;461:258–269. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.11.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan X, Skupin M, Siepmann J, Bodmeier R. Key parameters affecting the initial release (burst) and encapsulation efficiency of peptide-containing poly(lactide-co-glycolide) microparticles. Int J Pharm. 2006;324:168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao S, Guo C, Shi Y, Li LC. Recent advances in polymeric microspheres for parenteral drug delivery--part 1. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2012;9:1161–1176. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2012.709844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez MN, Rathbone MJ, Burgess DJ, Huynh M. Breakout session summary from AAPS/CRS joint workshop on critical variables in the in vitro and in vivo performance of parenteral sustained release products. J Control Release. 2010;142:2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyajima M, Koshika A, Okada Ji, Kusai A, Ikeda M. The effects of drug physico-chemical properties on release from copoly (lactic/glycolic acid) matrix. Int J Pharm. 1998;169:255–263. [Google Scholar]

- Panyam J, Dali MM, Sahoo SK, Ma W, Chakravarthi SS, Amidon GL, Levy RJ, Labhasetwar V. Polymer degradation and in vitro release of a model protein from poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) nano- and microparticles. J Control Release. 2003;92:173–187. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00328-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park TG. Degradation of poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) microspheres: effect of copolymer composition. Biomaterials. 1995;16:1123–1130. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(95)93575-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawat A, Burgess DJ. USP apparatus 4 method for in vitro release testing of protein loaded microspheres. Int J Pharm. 2011;409:178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawat A, Stippler E, Shah VP, Burgess DJ. Validation of USP apparatus 4 method for microsphere in vitro release testing using Risperdal Consta. Int J Pharm. 2011;420:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sah H. Microencapsulation techniques using ethyl acetate as a dispersed solvent: effects of its extraction rate on the characteristics of PLGA microspheres. J Control Release. 1997;47:233–245. [Google Scholar]

- Selmin F, Blasi P, DeLuca PP. Accelerated polymer biodegradation of risperidone poly(D, L-lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres. AAPS Pharm Sci Tech. 2012;13:1465–1472. doi: 10.1208/s12249-012-9874-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Burgess DJ. Accelerated in vitro release testing of implantable PLGA microsphere/PVA hydrogel composite coatings. Int J Pharm. 2012a;422:341–348. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Burgess DJ. Accelerated in-vitro release testing methods for extended-release parenteral dosage forms. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2012b;64:986–996. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2012.01482.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Choi S, Qu W, Wang Y, Burgess DJ. In vitro-in vivo correlation of parenteral risperidone polymeric microspheres. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society. 2015;218:2–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.09.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha VR, Trehan A. Biodegradable microspheres for protein delivery. J Control Release. 2003;90:261–280. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Burgess DJ. Microsphere Technologies. In: Wright JC, Burgess DJ, editors. Long Acting Injections and Implants. Springer US; 2012. pp. 167–194. [Google Scholar]

- Wischke C, Schwendeman SP. Principles of encapsulating hydrophobic drugs in PLA/PLGA microparticles. Int J Pharm. 2008;364:298–327. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolnik BS, Burgess DJ. Effect of acidic pH on PLGA microsphere degradation and release. J Control Release. 2007;122:338–344. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolnik BS, Leary PE, Burgess DJ. Elevated temperature accelerated release testing of PLGA microspheres. J Control Release. 2006;112:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolnik BS, Raton JL, Burgess DJ. Application of USP apparatus 4 and in situ fiber optic analysis to microsphere release testing. Dissol Technol. 2005;12:11–14. [Google Scholar]