Abstract

The White House Council (2014) has highlighted sexual assault prevention as a high priority issue in need of immediate attention. A risk factor associated with sexual assault victimization and revictimization is drinking before sexual activity. The current study examined the relationship between incapacitated sexual assault (ISA) and drinking before sexual activity. Additionally, social-related drinking factors including drinking to conform motives, social drinking motives, and perceived drinking norms were examined as being associated with ISA history and drinking before sexual activity given the typical social context of both drinking before sexual activity and sexual assault in college settings. Six hundred and three undergraduate college women completed a survey online assessing history of ISA, social factors associated with drinking, and frequency of drinking before sexual activity. Path analysis indicated that both ISA before college and since entering college were associated with higher perceived drinking norms, more social drinking motives endorsement, and more drinking to conform. However, only higher perceived drinking norms and more social drinking motives endorsement were associated with both more severe ISA histories and more frequent drinking before sexual activity. Thus, a more severe ISA history was indeed associated with more frequent drinking before sexual activity and social factors related to drinking played a significant role in this relationship. Social factors can be easily targeted through brief interventions and these findings can inform future programming to promote more careful use of alcohol in social and sexual situations.

Keywords: Incapacitated Sexual Assault, Drinking Motives, Drinking Norms, Alcohol Use, Sexual Activity

1. Introduction

The White House Council has highlighted college sexual assault as a high priority issue in need of immediate attention (2014). In fact, President Obama recently launched “It's On Us”, a public awareness campaign for sexual assault on college campuses (Somanader, 2014). Approximately 1 in 5 college women have experienced sexual assault (Krebs et al., 2009). Most assaults are perpetrated by a man known to the victim (Fisher, et al., 2000) and up to 70% of sexual assaults on college campuses involve alcohol use by the victim, the perpetrator, or both (Reed et al., 2009). Research suggests that sexual assault increases subsequent drinking (Bryan et al., in press; Kaysen, Neighbors, Martell, Fossos, & Larimer, 2006; Lindgren, Neighbors, Blayney, Mullins, & Kaysen, 2012). Therefore, it is essential to examine potential mechanisms that explain this relationship. Understanding such mechanisms can inform prevention and intervention efforts. The current study examined social drinking factors using indirect effects path analysis when assessing the relationship between incapacitated sexual assault (ISA) history and drinking before sexual activity. ISA is defined as unwanted sexual activity when the victim is incapacitated by alcohol and unable to give consent.

Alcohol use before sexual activity is common on college campuses. Among casual sexual encounters on college campuses, 60 to 80% involve alcohol consumption (Downing et al., 2009; Lewis et al., 2011). The prevalence of drinking before sexual activity and of ISA on college campuses highlights the need to examine drinking before sexual activity as a correlate of sexual assault. Furthermore, sexual activity in college frequently occurs in social contexts such as parties, at dormitories, fraternity houses, or at bars (Paul & Hayes, 2002). Given that perceived drinking norms are one of the strongest predictors of drinking in college (Neighbors et al., 2007), it is important to examine the role of drinking norms and other social motivation factors like drinking to conform and social drinking motives to understand the relationship between a history of sexual assault and current drinking before sexual activity.

1.1. Drinking before sexual activity

Little research has examined mechanisms of ISA victimization beyond the examination of heavy drinking as a mechanism through which ISA victimization may occur. Logically, drinking before sexual activity is associated with sexual victimization and ISA; yet it has received scant research attention. Previous cross-sectional studies show that sexual assault is associated with more frequent drinking before sexual activity (Howard & Wang, 2005; Testa & Dermen, 1999). Although the nature of sexual assaults is heterogeneous and spans a wide variety of tactics used by perpetrators, a substantial number of ISAs are preceded by consensual sexual contact (Harrington & Leitenberg, 1994). A bidirectional relationship may exist (Testa & Livingston, 2009; Testa & Parks, 1996) whereby drinking more before sexual activity is associated with ISA, which is associated with more drinking before sexual activity.

1.2. Sexual assault history and drinking

Sexual assault victimization is associated with the use of maladaptive coping strategies such as substance use (Najdowski & Ullman; 2011). Cross-sectionally, women's drinking habits (e.g. typical frequency and quantity of drinking, and problem drinking) are positively associated with their sexual assault history (Burnam et al., 1988; Kilpatrick et al., 1992; Koss & Dinero, 1989; Siegel & Williams, 2003). Longitudinal research also suggests that sexual assault is associated with subsequent alcohol use and abuse (Bryan et al., in press; Gidycz, Hanson, & Layman, 1995; Kilpatrick, Acierno, Resnick, Saunders, & Best, 1997; Lindgren, et al., 2012). However, some longitudinal studies find no link between sexual victimization and drinking (Mouilso & Fisher, 2012; Testa & Livingston; 2000). These studies did not differentiate between sexual victimization type (e.g. ISA compared to forced sexual assault) and two studies (Testa & Livingston, 2000; Yeater et al., 2014) did not include ISA. Cross-sectional shows that individuals with an ISA history compared to nonvictims show higher frequency and quantity of alcohol consumption, less use of drinking protective behavioral strategies, and more negative consequences from drinking (Gilmore et al., 2015; Marx, Nichols-Anderson, Messman-Moore, Miranda, & Porter, 2000; Nguyen, Kaysen, Dillworth, Brajcich, & Larimer, 2010). Additionally, one longitudinal study (Kaysen et al., 2006) found that ISA was associated with increased alcohol use and negative consequences in the subsequent years after the incident. Furthermore, women with an ISA history are at risk for ISA revictimization (Messman-Moore et al., 2013) and women with a sexual assault history before college are at heightened risk for experiencing sexual assault during college (Martin et al., 2011).

Alcohol use is a consistent risk factor for experiencing sexual assault (e.g., Gidycz et al., 2007; Messman-Moore et al., 2009; Testa et al., 2010). Women experience sexual assault when drinking more than their typical amount (Mouilso et al., 2012) and problematic alcohol use (Messman-Moore et al., 2013) and drinking before age 18 (Testa et al., 2003) are associated with ISA. Additionally, heavy episodic drinking increases the risk for ISA (McCauley et al., 2010) and in 85% of ISAs drinking is voluntary (Laywer et al., 2010).

1.4. Drinking Norms, Drinking to Conform and Social Drinking Motives

Descriptive drinking norms, the perceived norms about the alcohol use of one's peer group, are strongly related to drinking (Neighbors et al., 2007). College students overestimate the amount that their peers drink and these perceptions are associated with more alcohol use (Collins & Spelman, 2013; Quinn & Fromme, 2011). ISA is associated with higher estimates of peers’ drinking frequency in sexual minority women (Gilmore et al., 2014), however, nothing is known about the relationship between ISA and drinking norms in heterosexuals.

Motivations for drinking such as drinking to conform (i.e. drinking to avoid teasing or to fit in) and social drinking motives (i.e. drinking as a way to celebrate; Cooper, 1994) are also important to consider in the relationship between ISA and drinking before sexual activity. These social motivations have yet to be examined when assessing the relationship between drinking and sexual assault victimization. This dearth of research is surprising given that both drinking to conform and social motivations for drinking are conceptually related to drinking norms and the social contexts in which college students drink before sexual activity (Bogle, 2008; Cooper, 1994).

Social drinking motives are one of the most common reasons for drinking in young adults (Cooper, 1994; Kuntsche et al., 2005) and strongly predict more drinking in college students (Lewis et al., 2010). Additionally, drinking to conform and social drinking motives are associated with more drinking in social situations (Cooper, 1994), contexts where casual sex is common (Bogle, 2008; Grello et al., 2006), increasing their risk of being sexually assaulted. Indeed, ISAs often occur in social situations (Abbey et al, 1996; Testa et al., 2003). Perpetrators target women who are drinking alcohol and drinking men compared to nondrinking men are more likely to behave aggressively (see Abbey, 2002 for a review). Men perceive drinking women as more sexually interested than non-drinking women (Abbey, Zawacki, and McAuslan, 2000; George et al., 1977). Furthermore, the Cognitive Ecological Model of women's response to male sexual coercion (Nurius & Norris, 1996) suggests that women are less attuned to social cues of risk when making friends, socializing, and dating.

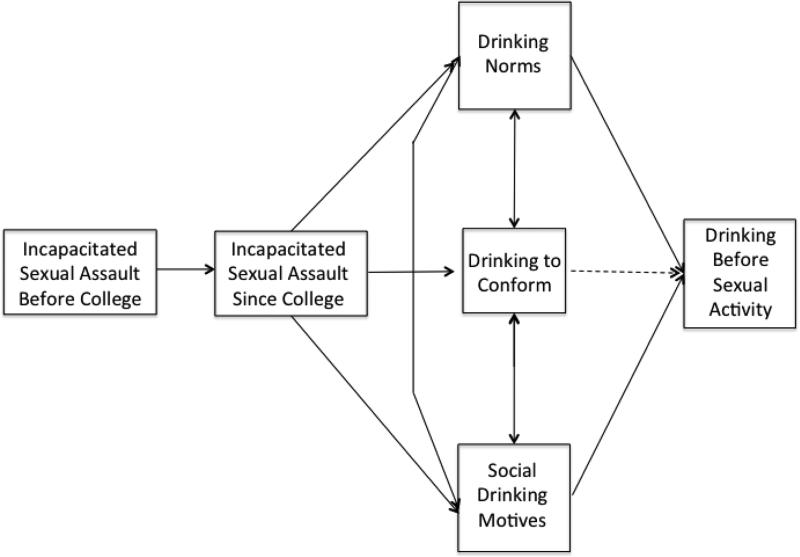

2. Current Research

For many, college provides a high alcohol consumption environment that thrives on social norms, social drinking, and pressure to conform (see Borsari & Carey, 2001 for a review) and intricately links alcohol and sexual activity (Owen et al., 2010). Given that ISA often occurs in social situations (Abby et al, 1996; Testa et al., 2003) and the tendency to drink before sexual activity is associated with ISA victimization (Howard & Wang, 2005; Testa & Dermen, 1999), it is imperative that we understand the social factors related to drinking before sexual activity and how they relate to ISA. Additionally, to the extant that ISA is associated with higher perceived drinking norms (Gilmore et al., 2014), a history of multiple ISAs and specifically ISA in college may be associated with higher perceived drinking norms and stronger endorsement of drinking motives related to social convention. The present research examines the roles of drinking norms, social drinking motives, and drinking to conform. We hypothesize that ISA history will be associated with perceptions of higher perceived drinking norms, more social drinking motives, and more drinking to conform, which will be associated with more drinking before sexual activity (see Figure 1). We predict that ISA history and more drinking before sexual activity will be indirectly associated through these social drinking factors.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized path model.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedures

Participants (n = 620) completed a web-based survey and 17 were excluded due to missing the variables examined in the current study (final n = 603). Participants were recruited from introductory psychology courses for a study about “drinking and sexual behaviors” using the university's Psychology Subject Pool and completed the survey online. Participants were given course credit for completing the survey.

Participants were 18.78 years old on average (SD = .838). The majority (62.9%) of participants had been in college for less than a year, were not a member of a sorority (79.6%), spoke English as a first language (65%), and lived in residence halls or dorm rooms (50.4%) or off-campus (24.6%). The majority of participants were White (39.8%) or Asian American/Pacific Islander (41.8%) and 9.6% were multiracial, 2.8% were Black/African American, 2.5% identified as “Other”, .7% were American Indian/Alaska Native, and 1.5% chose to not identify their race. Additionally, 8.0% of participants identified as Hispanic/Latina.

3.2. Measures

Incapacitated Sexual Assault

Using the Sexual Experiences Survey (Koss et al., 2007), participants were asked to report coerced sexual experiences at two time points: after their 14th birthday, but before entering college, and since entering college. The SES is a behaviorally specific assessment of sexual assault and the current study included perpetrations by incapacitation (“Taking advantage of me when I was too drunk or out of it to stop what was happening”). Sexual assault experiences included both attempted and completed oral, vaginal, and anal coerced sex. Participants were asked to indicate the number of times that this tactic was used (0 = 0 times, 1 = 1 time, 2 = 2 times, and 3 = 3 or more times).

Drinking Norms

The modified version of the Drinking Norms Rating Form (Baer et al., 1991) was used to determine participants’ perception of alcohol use at the participant's university. Participants were asked how many drinks they perceived the typical female student at the participant's university drinks on each day of the week. Perceived drinks per week were calculated by adding the number of perceived drinks per day.

Drinking to Conform and Social Drinking Motives

Participants were asked questions about drinking to conform and social drinking motives from the Drinking Motives Questionnaire – Revised Short-Form (Grant et al., 2007). To measure drinking to conform, participants were asked how often in the past 12 months they drank based on 5 different items including drinking “to be liked,” and “so I won't feel left out.” Answer choices ranged on a 5-point scale (1 = almost never or never, 2 = some of the time, 3 = half of the time, 4 = most of the time, and 5 = almost always or always. Internal reliability of the subscale was acceptable (α = .81). To measure social drinking motives, participants were asked how often in the past 12 months they drank based on 5 different items including “drinking as a way to celebrate,” “because my friends pressured me to drink” and “because it is what most of my friends do when we get together”. Answer choices ranged on a 5-point scale (1 = almost never or never, 2 = some of the time, 3 = half of the time, 4 = most of the time, and 5 = almost always or always. Internal reliability of the subscale was acceptable (α = .83). Scores for each subscale were created by taking the mean of the items for each subscale.

Alcohol Use Before Sexual Activity

Participants were asked how often they consume alcohol prior to or during sexual activity. Answer choices ranged on a 5-point scale (0 = never, 1 = about a quarter of the time, 2 = about half of the time, 3 = about three quarters of the time, and 4 = always.

3.3. Data Analysis Plan

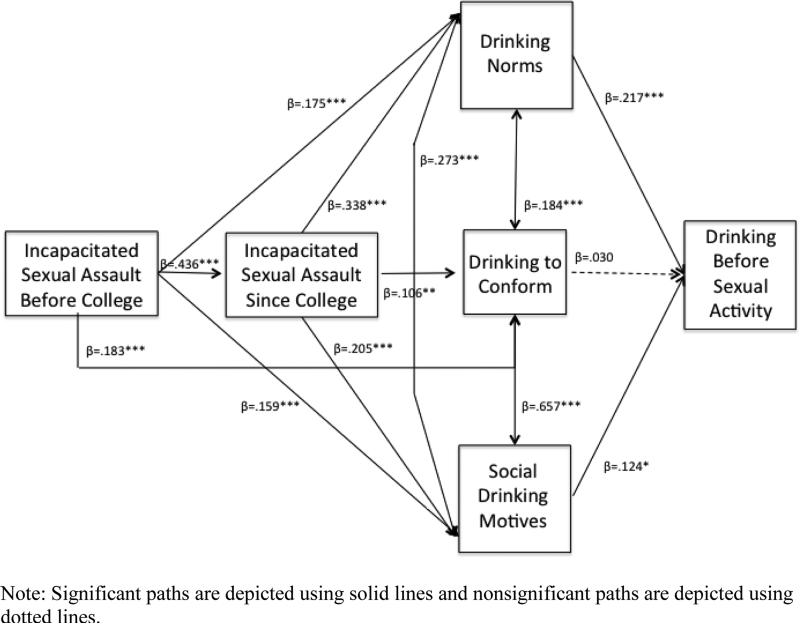

The hypothesized (see Figure 1) and final path models (see Figure 2) were tested in Mplus 7. Maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors was used for missing data. To assess model fit, chi square, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), and standard root mean square residual (SRMR) were used. Good model fit was indicated with a non-significant chi square, RMSEA values less than .06, CFI values greater than .90, and SRMR values less than .06 (Kline, 2005).

Figure 2.

Final path model

An alternate model was tested due to the cross-sectional nature of the data based on the timing of the questions in the assessment. In this model, a path from ISA before college to ISA since college was modeled. Paths from ISA since college to social and conform drinking motives (which were allowed to freely associate with each other), and paths from social and conform drinking motives were modeled to drinking norms and drinking before sexual activity (which were allowed to freely associate with each other). If both models prove to be a good fit for the data, evaluations of better fit will be conducted.

4. Results

Means, standard deviations, and correlations for the variables included in the model are shown in Table 1. A total of 10.45% of participants (n = 63) reported a history of ISA before college, with 3.3% (n = 20) reporting one victimization experience, 3.0% (n = 18) reporting two victimization experiences, and 4.1% (n = 25) reporting three or more victimization experiences. A total of 8.13% of participants (n = 43) reported a history of ISA since college , with 4.8% (n = 29) reporting one victimization experience, 1.5% (n = 9) reporting two victimization experiences, and 1.8% (n = 11) reporting three or more victimization experiences.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations of all variables

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | |||||||

| 1. ISABC | .22(.69) | __ | .436** | .061 | .229** | .249** | .322** |

| 2. ISAC | .13(.51) | __ | .178** | .186** | .274** | .415** | |

| 3. Drinking Norms | 12.25(8.75) | __ | .169** | .222** | .269** | ||

| 4. Drinking to Conform | 1.46(.66) | __ | .680** | .265** | |||

| 5. Social Drinking Motives | 2.07(.93) | __ | .369** | ||||

| 6. Drinking before sex | .41(.77) | __ | |||||

Note: ISABC = Incapacitated sexual assault before college; ISAC = Incapacitated sexual assault since college. Correlations of all variables were also examined within our two largest ethnic groups, Asian and Pacific Islander and Caucasian. Correlations followed the same pattern for both groups and thus, separate path models were not run to examine ethnic groups separately.

*p < .05;

p < .01

The hypothesized model (Figure 1) was a poor fit for the data so paths were added from ISA before college to all three of the social drinking factors due to suggestions from the Model Modification Indices. The final model (Figure 2) was a good fit for the data, χ2 (2) = 4.926, p = .085, RMSEA = .049, CFI = .996, and SRMR = .013. Drinking norms, drinking to conform, and social drinking motives were free to correlate in the model.

The standardized coefficients for the paths are presented in Figure 2. More ISA before college was associated with more ISA since college. More ISA since college was associated with higher perceived drinking norms, more drinking to conform, and more social drinking motives. Additionally, however, more ISA before college was also associated with higher perceived drinking norms, more drinking to conform, and more social drinking motives-- paths that were added to find the final model. Both higher perceived drinking norms and more social drinking motives were associated with more drinking before sex, but drinking to conform was not significantly associated.

Indirect effects were examined for the paths from ISA before college to drinking before sexual activity. More ISA before college was significantly indirectly associated with more drinking before sexual activity through more ISA since college and higher perceived drinking norms (β = .032, p = .001) and through more ISA since college and more social drinking motives (β = .011, p = .045), but not through ISA since college and drinking to conform (β = .001, p = .587). More ISA history before college was associated with more ISA since college, which was associated with higher perception of drinking norms and social drinking motives, which were associated with more drinking before sexual activity.

The alternate model was a poor fit for the data and paths were added from ISA before college and ISA since college to drinking norms due to suggestions from the Model Modification Indices. The final model was still a poor fit for the data, χ2 (4) = 16.586, p = .0023, RMSEA = .072, CFI = .984, and SRMR = .030.

5. Discussion

Little research has examined ISA and drinking outcomes and even fewer studies have examined the relationship between ISA and drinking before sexual activity. This is the first study to examine social drinking factors as mechanisms in this relationship. The original hypothesized model did not fit, however, after modifying the model to account for the relationship between all ISA history rather than simply the most recent ISA, the model fit the data well. It was found that ISA experiences were positively associated with perceived drinking norms and social motives for drinking, which were both positively associated with drinking before sexual activity.

The finding that more ISA was associated with higher perceived drinking norms was consistent with previous findings in a sample of sexual minority women (Gilmore et al., 2014). The current study extends previous research in a heterosexual sample of college women (95.4% heterosexual) and by examining other social influences of drinking. Drinking to conform was not associated with drinking before sexual activity and this may be because some research has found that drinking to conform is less associated with drinking in college freshman than in other years of college (Martens et al., 2008). Given that the majority of the current sample were college freshman, it is not surprising that drinking to conform was not a driving factor. In contrast, social drinking motives were positively associated with both ISA history and drinking before sexual activity. Social drinking motives take into account positive (as opposed to negative) motives for drinking, which may occur frequently in the context of casual sex.

5.1. Limitations and Future Directions

Most research assessing the association between sexual assault history and current drinking examines drinking to cope as a primary factor driving the relationship. However, this is the first study to our knowledge to focus on social factors. Given that the current data were cross-sectional, it is not possible to make causal or directional conclusions. Future research using mediation and multiple time points is necessary. For example, an examination of ISA in college as the outcome variable is warranted using longitudinal methodologies.

Additionally, measurement of drinking motives (to conform and social motives) was assessed of the past 12 months. Not all participants had been in college for a full 12 months; therefore, this measurement may capture experiences that did not occur during college. Future work could replicate the current study in pre-college and college samples to clarify college specific processes. Measurement of these social drinking factors is not specific to particular drinking contexts, such as drinking before sexual activity. Previous work has examined context specific peer drinking norms (Neighbors, Oster-Aaland, Bergstrom, & Lewis, 2006) and future work could examine perceived drinking during sexual activity norms and motives to drink during sexual activity to clarify the nature of these drinking norms. Similarly, the definition of ISA continues to be ambiguously defined and measured. In reality, ISAs likely include both complete incapacitation and partial incapacitation where the victim is not unconscious but is unable to consent. To move research forward, it is imperative that we as a field more clearly define ISA.

Additionally, the sample consisted of women under the age of 21 due to their high risk of sexual assault victimization, limiting generalizability to women of other ages. Finally, the majority of the sample was White or Asian American. It is a strength that there is such a large number of Asian American women within this sample, however, because that population is overrepresented in this sample, results may not be generalizable to the broader college population. Future research should also examine potential cultural differences among ethnicities in the relationship between these social factors and the ISA.

Finally, this work is limited in terms of the field's goal to reduce sexual assault on a population level. In order for large shifts in rates to occur, perpetrators must be targeted for interventions. However, a tendency to drink before sexual activity is one factor that has been associated with incapacitated sexual assault and a better understanding of the social drinking factors associated with this tendency contribute to decreasing rates of sexual assaults that involve alcohol.

5.2. Conclusion

Social factors related to drinking, including perceived drinking norms and social drinking motives are important to consider in the relationship between sexual assault history and drinking before sexual activity. Specifically, it was found that severity of ISA was positively associated with social motives for drinking, conformity motives for drinking, and perceived drinking norms. However, only social motives and perceived drinking norms were associated with more drinking before sexual activity. It is important to target these behaviors during prevention and intervention work. Universities are beginning to implement and restructure their sexual assault prevention and intervention programs and the present work suggests that social dynamics regarding drinking may be key factors to target through interventions at the peer level if we are to reduce rates of incapacitated sexual assault.

Highlights.

Incapacitated sexual assault (ISA) is common among college students.

Examined relationships among ISA, social drinking factors, and drinking before sex.

ISA was indirectly associated with drinking before sex.

Drinking norms and social drinking motives were associated with ISA and drinking.

Interventions targeting ISA should include social drinking factors.

Acknowledgements

Data collection and manuscript preparation were supported by grants from the National Institute for Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) awarded to A. K. Gilmore (F31AA020134) as well as a grant from the Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute at the University of Washington, as well as the Bolles Fellowship and Hunt Fellowship from the University of Washington awarded to A. K. Gilmore. Manuscript preparation was also supported by grants from NIAAA awarded to W. H. George (R01NIAAA; AA016281) and to M. A. Lewis (R01AA021379).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abbey A. Alcohol-related sexual assault: A common problem among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. Supplement. 2002;14:118–128. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Parkhill MR, Koss MP. The effects of frame of reference on responses to questions about sexual assault victimization and perpetration. Psychology Of Women Quarterly. 2005;29:364–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2005.00236.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Ross LT, McDuffie D, McAuslan P. Alcohol and dating risk factors for sexual assault among college women. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1996;20:147–169. [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Zawacki T, McAuslan P. Alcohol's effects on sexual perception. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:688–697. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Stacy A, Larimer M. Biases in the perception of drinking norms among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 1991;52:580–586. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogle KA. Hooking up: Sex, dating, and relationships on campus. New York University Press; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;13:391–424. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan AEB, Norris J, Abdallah DA, Stappenbeck CA, Morrison DM, Davis KC, Zawacki T. Longitudinal change in women's sexual victimization experiences as a function of alcohol consumption and sexual victimization history: A latent transition analysis. Psychology of Violence. doi: 10.1037/a0039411. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnam MA, Stein JA, Golding JM, Siegel JM, Sorenson SB, Forsythe AB, Telles CA. Sexual assault and mental disorders in a community population. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:843–850. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Classen CC, Gronskaya Palesh O, Aggarwal R. Sexual revictimization: A review of the empirical literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2005;6:103–129. doi: 10.1177/1524838005275087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins S,E, Spelman PJ. Associations of descriptive and reflective injunctive norms with risky college drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27:1175–1181. doi: 10.1037/a0032828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations of alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cronce JM, Larimer ME. Individual-focused approaches to the prevention of college student drinking. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews. 2011;34:210–221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt G. Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS): A harm reduction approach. Guilford Press; New York, NY, US: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Downing-Matibag TM, Geisinger B. Hooking up and sexual risk taking among college students: A health belief model perspective. Qualitative Health Research. 2009;19:1196–1209. doi: 10.1177/1049732309344206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher BS, Cullen FT, Turner MG. The sexual victimization of college women: Findings from two national-level studies. U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; Washington, D.C.: 2000. [August 12, 2014]. from https://www.ncjrs.gov/txtfiles1/nij/182369.txt. [Google Scholar]

- George WH, Lehman GL, Cue KL, Martinez LJ, Lopez PA, Norris J. Postdrinking sexual inferences—Evidence for linear rather than curvilinear dosage effects. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1997;27:629–648. [Google Scholar]

- Gidycz CA, Hanson K, Layman MJ. A prospective analysis of the relationships among sexual assault experiences: An extension of previous findings. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1995;19:5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gidycz CA, Loh C, Lobo T, Rich C, Lynn S, Pashdag J. Reciprocal relationships among alcohol use, risk perception, and sexual victimization: A prospective analysis. Journal of American College Health. 2007;56:5–14. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.1.5-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore AK, Koo KH, Nguyen HV, Granato HF, Hughes TL, Kaysen D. Sexual assault, drinking norms, and drinking behavior among a national sample of lesbian and bisexual women. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39:630–636. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant VV, Stewart SH, O'Connor RM, Blackwell E, Conrod PJ. Psychometric evaluation of the five-factor Modified Drinking Motives Questionnaire—Revised in undergraduates. Addictive behaviors. 2007;32:2611–2632. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayson CE, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Motives to drink as mediators between childhood sexual assault and alcohol problems in adult women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18:137–145. doi: 10.1002/jts.20021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grello CM, Welsh DP, Harper MS. No strings attached: The nature of casual sex in college students. The Journal of Sex Research. 2006;43:255–267. doi: 10.1080/00224490609552324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington NT, Leitenberg H. Relationship between alcohol consumption and victim behaviors immediately preceding sexual aggression by an acquaintance. Violence and Victims. 1994;9:315–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard DE, Wang MQ. Psychosocial correlates of U.S. adolescents who report forced sexual intercourse. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;36:372–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D, Neighbors C, Martell J, Fossos N, Larimer ME. Incapacitated rape and alcohol use: A prospective analysis. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:1820–1832. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Resnick HS, Saunders BE, Best CL. A 2-year longitudinal analysis of the relationships between violent assault and substance use in women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:834–847. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Dinero TE. Discriminant analysis of risk factors for sexual victimization among a national sample of college women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57:242–250. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.2.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Abbey A, Campbell R, Cook S, Norris J, Testa M, Ullman S, West C, White J. Revising the SES: A collaborative process to improve assessment of sexual aggression and victimization. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2007;31:357–370. [Google Scholar]

- Krebs CP, Lindquist CH, Warner TD, Fisher BS, Martin SL. College women's experiences with physically forced, alcohol- or other drug-enabled, and drug-facilitated sexual assault before and since entering college. Journal of American College health. 2009;57:639–647. doi: 10.3200/JACH.57.6.639-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawyer S, Resnick H, Bakanic V, Burkett T, Kilpatrick D. Forcible, drug-facilitated, and incapacitated rape and sexual assault among undergraduate women. Journal of American College Health. 2010;58:453–460. doi: 10.1080/07448480903540515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Granato H, Blayney JA, Lostutter TW, Kilmer JR. Predictors of hooking up sexual behavior and emotional reactions among U.S. college students. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;41:1219–1229. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9817-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C, Geisner I, Lee CM, Kilmer JR, Atkins DC. Examining the associations among severity of injunctive drinking norms, alcohol consumption, and alcohol-related negative consequences: The moderating roles of alcohol consumption and identity. Psychology Of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:177–189. doi: 10.1037/a0018302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren KP, Neighbors C, Blayney J. a., Mullins PM, Kaysen D. Do drinking motives mediate the association between sexual assault and problem drinking? Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(3):323–326. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Rocha TL, Martin JL, Serrao HF. Drinking motives and college students: Further examination of a four-factor model. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2008;55:289–295. [Google Scholar]

- Martin SL, Fisher BS, Warner TD, Krebs CP, Lindquist CH. Women's sexual orientations and their experiences of sexual assault before and during university. Women's Health Issues. 2011;21:199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley JL, Calhoun KS, Gidycz CA. Binge drinking and rape: A prospective examination of college women with a history of previous sexual victimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25:1655–1668. doi: 10.1177/0886260509354580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Ward RM, Brown AL. Substance use and PTSD symptoms impact the likelihood of rape and revictimization in college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24:499–521. doi: 10.1177/0886260508317199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Ward R, M., Zerubavel N. The role of substance use and emotion dysregulation in predicting risk for incapacitated sexual revictimization in women: Results of a prospective investigation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27:125–132. doi: 10.1037/a0031073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouilso ER, Fischer S. A prospective study of sexual assault and alcohol use among first-year college women. Violence and Victims. 2012;27:78–94. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.27.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najdowski CJ, Ullman SE. The effects of revictimization on coping and depression in female sexual assault victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2011;24:218–221. doi: 10.1002/jts.20610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, Larimer ME. Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy-drinking college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:556–565. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Oster-Aaland L, Bergstrom RL, Lewis MA. Event-and context specific normative misperceptions and high-risk drinking: 21st birthday celebrations and football tailgating. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2006;67:282–289. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen JJ, Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, Fincham FD. “Hooking up” among college students: Demographic and psychosocial correlates. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010;39:653–663. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9414-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul EL, Hayes KA. The casualties of “casual” sex: A qualitative exploration of the phenomenology of college students’ hookups. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2002;19:639–661. [Google Scholar]

- Reed E, Amaro H, Matsumoto A, Kaysen D. The relation between interpersonal violence and substance use among a sample of university students: Examination of the role of victim and perpetrator substance use. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:316–318. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey KB, Elliott JC, Garey L. Efficacy of alcohol interventions for first-year college students: A meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82:177–188. doi: 10.1037/a0035192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JA, Williams LM. Risk factors for sexual victimization of women: Results from a prospective study. Violence Against Women. 2003;9:902–930. [Google Scholar]

- Somanader T. President Obama launches the “It's On Us” campaign to end sexual assault on campus. The White House Blog; 2014. Retrieved from http://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/2014/09/19/president-obama-launches-its-us-campaign-end-sexual-assault-campus. [Google Scholar]

- Stappenbeck CA, Norris J, Kiekel PA, Morrison DM, George WH, Davis KC, Zawacki T, Jacques-Tiura AJ, Abdallah DA. Patterns of alcohol use and expectancies predict sexual risk taking among non-problem drinking women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2013;74:223–232. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia: Its prized and dangerous effects. American Psychologist. 1990;45:921–933. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Dermen KH. The differential correlates of sexual coercion and rape. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1999;14:548–561. [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Hoffman JH, Livingston JA. Alcohol and sexual risk behaviors as mediators of the sexual victimization–revictimization relationship. Journal of Consulting And Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:249–259. doi: 10.1037/a0018914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Livingston JA. Alcohol and sexual aggression: Reciprocal relationships over time in a sample of high-risk women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2000;15:413–427. [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Livingston JA. Alcohol consumption and women's vulnerability to sexual victimization: Can reducing women's drinking prevent rape?. Substance Use & Misuse. 2009;44:1349–1376. doi: 10.1080/10826080902961468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Livingston JA, VanZile-Tamsen C, Frone MR. The role of women's substance use in vulnerability to forcible and incapacitated rape. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:756–764. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Parks KA. The role of women's alcohol consumption in sexual victimization. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 1996;1:217–234. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE. A critical review of field studies on the link of alcohol and adult sexual assault in women. Aggression And Violent Behavior. 2003;8:471–486. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh K, Danielson CK, McCauley J, Hanson RF, Smith DW, Resnick HS, et al. Longitudinal trajectories of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and binge drinking among adolescent girls: The role of sexual victimization. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50:54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman L. Bayesian model selection and model averaging. Journal of Mathematical Psychology. 2000;44:92–107. doi: 10.1006/jmps.1999.1278. doi: 10.1006/jmps.1999.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White House Council on Women and Girls Rape and sexual assault: A renewed call to action. 2014 http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/docs/sexual_assault_report_1-21-14.pdf.

- Yeater EA, Montanaro EA, Bryan AD. Predictors of sexual coercion and alcohol use among female juvenile offenders. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0166-z. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn PD, Fromme K. Alcohol use and related problems among college students and their noncollege peers: The competing roles of personality and peer influence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:622–632. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]