Abstract

Background and Aims: Schistosomiasis is a major chronic disease of humans in endemic regions, and infected individuals may develop a spectrum of pathology, including hepatic fibrosis, hepatosplenomegaly, and portal hypertension. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is considered the fifth most common cancer in the world, and there is limited and controversial evidence suggesting that Schistosoma mansoni infection may be a possible risk factor for HCC. The aim of this study was to report a case series of patients with HCC and S. mansoni infection and to conduct a literature review on the topic. Methods: From January 2002 to January 2015, an institutional database was screened retrospectively to identify patients with HCC and S. mansoni infection at a single center in the Department of Gastroenterology of University of São Paulo School of Medicine and Hospital das Clínicas, Brazil. Results: Seven cases were included. The mean age of patients was 62.1±10.3 years; six (85.7%) were male and one (14.3%) was female. All cases had positive epidemiology, coming from endemic areas of S. mansoni infection in Brazil, and four (57.1%) had previous complications (upper gastrointestinal bleeding) related to portal hypertension or surgery intervention (splenectomy) performed more than 10 years before the HCC diagnosis. Nontumoral portal vein thrombosis was identified in five (71.4%) patients. All patients had negative serology for HCV, and four (57.1%) had positivity of HBVcore antibodies without evidence of viral replication. According to BCLC staging, one (14.3%) patient was BCLC A and received TACE instead of RFA because HCC size was >30 mm; three (42.8%) BCLC B patients received sorafenib instead of local regional treatment due to the presence of nontumoral TPV. During follow-up, all patients developed tumoral progression and died. Conclusions: It remains unclear if S. mansoni infection alone has carcinogenic potential. The available literature indicates that S. Mansoni, in the presence of HBV and HCV infections, likely acts as a cofactor for the hepatic lesion and potentiates injury.

Keywords: Schistosoma mansoni, Schistosomiasis, Hepatocellular carcinoma

Introduction

Schistosomiasis is the second most common parasitic infection of humans, following malaria, worldwide.1,2 Approximately 207 million people are infected in 76 countries, and about 600 million are exposed to infection in tropical and subtropical regions of Africa, Asia, South America, and the Caribbean. Globally, 200,000 deaths are attributed to schistosomiasis annually.1–3

Advances in the fields of molecular biology and epidemiology have led to significant advances in our understanding of the relationship between infectious agents and cancer; however, the high prevalence of the parasitic infection in the general population, the extended latency, as well as the presence of interacting factors make detection of this relationship difficult.1,4

Five species of Schistosoma infect humans: S. hematobium, S. mansoni, S. japonicum, S. intercalatum, and S. mekongi.2,4 Most human infections are linked to S. haematobium, S. japonicum – strongly associated with bladder cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), respectively – and S. mansoni, which has been linked to many case reports of liver cancer, colorectal cancer, prostate cancer, and giant follicular lymphomas.4,5

In Brazil, schistosomiasis is caused by S. mansoni, and the intermediate hosts are snails of the genus Biomphalaria (B. straminea, B. glabrata, and B. tenagophila).6,7 The immunopathology of S. mansoni infection is due to granuloma formation surrounding the eggs deposited in the tissues, which is a manifestation of the delayed hypersensibility reaction. This reaction leads to pylephlebitis, peripylephlebitis, portal hypertension, splenomegaly, esophageal varices, hematemesis, and death.1–7

HCC is considered the fifth most common cancer in the world and is responsible for 5% of all malignant tumors in humans. In recent years, the incidence of schistomiasis has risen in many countries, including those in North America, Europe, and Asia.8–10 Most HCC cases develop in the presence of advanced chronic liver disease related to chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, and alcohol abuse.1,2,4,5

The relationship between HCC and S. mansoni has been debated in human cases.4,11,12 The real role of S. mansoni infection in the development of HCC has not been well characterized.

The aim of this study was to report a case series of patients with HCC and S. mansoni infection at a single center from January 2002 to January 2015 and to conduct a literature review on the topic.

Patients and methods

From January 2002 to January 2015, an institutional database was screened retrospectively to identify patients with HCC and S. mansoni infection at a single center in the Department of Gastroenterology of University of São Paulo School of Medicine and Hospital das Clínicas, Brazil. Baseline information, including patient demographics, serum biochemistries, liver biopsy when available, severity of liver disease (Child-Pugh classification), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (PST), cancer stage according to the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system, α-fetoprotein level (AFP), and treatment modalities, were acquired.

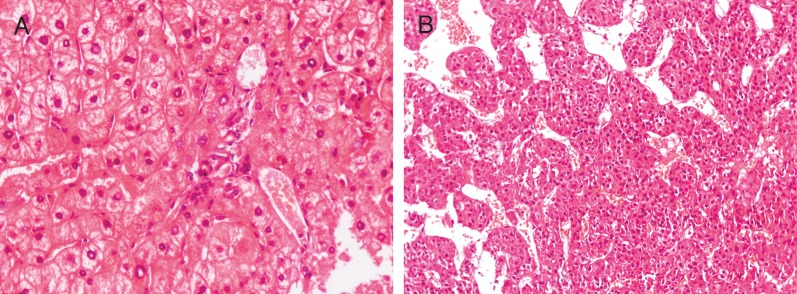

Diagnosis of S. mansoni infection was made based on positive epidemiology (coming or visiting from endemic areas with a history of exposure to potentially contaminated water or food), history of drug treatment for schistosomiasis or surgery (splenectomy), imaging patterns (periportal fibrosis, left lobe hypertrophy, or splenomegaly), positive stools, and/or presence of compatible histological findings (presence of Schistosoma granuloma, portal fibrosis, or obliteration of portal venous branches) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Pathological aspects of case 1.

A, Small portal tract with aberrant veins and obliterative venopathy, suggestive of schistosomiasis; B, Hepatocellular carcinoma, trabecular pattern.

HCC was diagnosed according to the updated noninvasive diagnostic criteria of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.8 Liver histology was performed to confirm diagnosis in inconclusive cases by imaging examination. All patients underwent abdominal ultrasound and abdominal dynamic contrast-enhanced computed tomography. For staging, chest computed tomography and a bone scan were performed. Patients were classified as 0 (very early), A (early), B (intermediate), C (advanced), or D (terminal), using the BCLC staging system.

Curative therapies included surgical resection, liver transplantation, and local ablative therapy, such as radiofrequency ablation (RFA) or percutaneous ethanol injection. Liver transplantation was considered in patients fulfilling the Milan criteria and showing increased portal pressure or bilirubin. While waiting on the liver transplant list, patients were treated with percutaneous ablation or transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) as a bridge therapy to liver transplantation. If hepatectomy or orhtotopic liver transplantation were not indicated, local ablative therapies were performed, depending on the size and number of tumor nodules. In multifocal tumors or large HCCs without extra-hepatic spread or vascular invasion, TACE was the treatment of choice. Sorafenib was indicated for patients with advanced HCC. When treatment efficacy was considered limited or treatment-related risk was substantial due to extensive tumor burden, Child-Pugh class C status, or other medical comorbidities, supportive care was given.

Results

Ten cases were initially identified with HCC and S. mansoni infection in our center, however, three cases were excluded: one female patient had a biopsy consistent with Budd-Chiari syndrome, one male patient had impaired liver function (Child C10), and one male patient who underwent the liver orthotopic transplantation with explant showed liver cirrhosis. A summary of the seven included cases is shown in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1. Clinicopathological features of seven patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and Schistosoma mansoni infection.

| Characteristics | All patients |

|---|---|

| Gender (male/female, %) | 85.7/14.3 |

| Age (years, median, DP) | 62.1±10.3 |

| Epidemiology (n, %) | 7 (100.0%) |

| Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (n, %) | 4 (57.1%) |

| Splenectomy (n, %) | 4 (57.1%) |

| Non-tumoral portal vein thrombosis (n, %) | 5 (71.4%) |

| Anti-HBcT +, Anti-HBs +, HBsAg − (n, %) | 4 (57.1%) |

| AFP >100 ng/mL (n, %) | 2 (28.6%) |

| HCC stage | |

| Single tumor (n, %) | 4 (57.1%) |

| Tumor size (median, range) (mm) | 62.6 (40-110) |

| Vascular invasion (n, %) | 1 (14.3%) |

| Metastases (n, %) | 0 (0.00%) |

| ECOG PST | 1 (14.3%) |

| BCLC stage (n, %) | |

| A | 1 (14.3%) |

| B | 5 (71.4%) |

| C | 1 (14.3%) |

| D | 0 (0.00%) |

| Therapy | |

| TACE | 3 (42.8%) |

| Sorafenib | 3 (42.8%) |

| Palliative care | 1 (14.3%) |

AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; HBcT, hepatitis B core total; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; ECOG PST, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; TACE, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization.

Table 2. Epidemiological, clinical, biochemical, and histological parameters of the seven patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and Schistosoma mansoni infection.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | M | M | M | M | M | F | M |

| Age (years) | 65 | 79 | 67 | 61 | 51 | 64 | 48 |

| Epidemiology | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| UGB | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Splenectomy/year | Y/NA | N | Y/1960 | Y/1974 | N | N | Y/1979 |

| PVT | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| HBV contact | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N |

| HCC histology | MD | N | MD | N | N | N | MD |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 4.0 | 2.9 | 6.8 | 4692.0 | 2563.0 | 10.5 | 26.0 |

| Nodules (number) | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| HCC size (mm) | 70 | 110 | 57 | 40 | 72 | 40 | 49 |

| Metastases | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Vascular invasion | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N |

| ECOG PS | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| BCLC | B | C | B | B | B | A | B |

| HCC Therapy | TACE | Palliative | Sorafenib | Sorafenib | TACE | TACE | Sorafenib |

M, male; F, female; Y, yes; N, no; NA, not available; UGB, upper gastrointestinal bleeding; TPV, thrombosis of portal vein; HBV contact, HBsAg negative, total anti-HBc positive, anti-HBs positive; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MD, moderately differentiated; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; ECOG PST, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer criteria; TACE, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization.

The mean age of patients was 62.1±10.3 years. Of the seven patients with HCC and S. mansoni infection, six (85.7%) were male and one (14.3%) was female. All cases had positive epidemiology, coming from endemic areas of S. mansoni infection in Brazil, and four (57.1%) had previous complications (upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGB)) related to portal hypertension or surgery intervention (splenectomy) performed more than 10 years before the HCC diagnosis. Nontumoral portal vein thrombosis (PVT) was identified in five (71.4%) patients. No hematological disease was identified in our sample. All patients had negative serology for HCV, and four (57.1%) had positivity of HBVcore (HBc) antibodies without evidence of viral replication. Other causes of chronic liver disease, such as autoimmune hepatitis, α-1 antitripsin deficiency, Wilson’s disease, and hemochromatosis, were excluded by the appropriate laboratory tests.

According to BCLC staging, one (14.3%) patient was BCLC A and received TACE instead of RFA because HCC size was >30 mm; three (42.8%) BCLC B patients received sorafenib instead of local regional treatment due to the presence of nontumoral TPV. During follow-up, all patients developed tumoral progression and died.

Discussion

Schistosomiasis is a major chronic disease of humans in endemic regions.1–5,13 While the majority of people infected with S. mansoni are relatively asymptomatic or show restricted morbidity associated with intestinal inflammation and fibrosis, a minority of infected individuals develop a severe hepatosplenic schistosomiasis, characterized by hepatic fibrosis, hepatosplenomegaly, and portal hypertension.13

This infection has an extensive transmission area in Brazil, with endemic and focal areas encompassing 19 of the 27 federative units/states.6,14 The most heavily affected areas are characterized by poor sanitary conditions, poverty, and low education levels, especially in states of the Northeast and Southeast regions. It is estimated that approximately 2.5 to 6.0 million people are infected (5-10% may develop severe hepatosplenic and potentially fatal forms) and that 25 million who live in endemic areas are at risk of infection.14

Humans are infected with S. mansoni following exposure to contaminated water; S. mansoni cercariae infect the host via the penetration of intact skin and become a new form called schistosomulum. After penetrating the wall of a nearby vein, schistosomula are carried in the host’s blood, eventually reaching the portal venous system, where they mature and lay eggs, which either lodge into tissues and incite a granulomatous reaction or are released in feces. The eggs hatch in water to form miracidia, which invade snails and are released as cercarie, starting a new cycle.1–7,13

Infections, in general, can initiate or promote carcinogenesis by three main mechanisms: (a) chronic inflammation due to prolonged persistence of an infectious agent in the host promotes release of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNOS, respectively), which have the potential to damage DNA, proteins, and cell membranes, and modulates enzyme activities and gene expression, which can cause carcinogenesis; (b) insertion of oncogenes into the host genome, as in hepatitis B and hepatitis C, inhibition of tumor suppressors, or stimulation of mitosis; and (c) induction of immunosuppression and consequently a reduction in immunosurveillance. Parasitic infections that initiate or promote neoplasia usually do so by mechanism one.1,2,4,5,11,15

In our sample, all patients had positive epidemiology for S. mansoni infection, and five (71.4%) previously had UGB or surgery intervention more than 10 years before the HCC diagnosis. Previous drug treatment for S. mansoni infection and the long period until the HCC disclosure could explain the negative results for the S. mansoni eggs in stool tests.

Several surgical techniques have been developed to prevent rebleeding in patients with schistosomiasis and esophageal varices. After isolated splenectomy, much of the portal blood flow is diverted through the left gastric vein into the azygos system. Consequently, the liver becomes extremely arterialized with greatly increased sinusoidal pressure, leading to loss of liver function in the long term.16,17

Splenectomy and ligature of the left gastric vein has been used in hepatosplenic schistosomiasis since the 1960s in Brazil, becoming widespread in the 1990s.17 In our sample, patients underwent splenectomy in external services. Based on clinical and surgical data, year of fulfillment, and place the surgery was performed, it was possible to infer that two (cases 4 and 7) of the four patients in our sample underwent ligation of the left gastric vein.

Schistosomiasis fibrosis is accompanied by numerous vascular changes within the host. The peripheral destruction of the portal vein system with the occlusion or amputation of some of the medium-sized branches account for the presence of portal hypertension. The hepatic arterial changes, with hypertrophy and hyperplasia, are considered compensatory for the diminution of the portal vein flux.18

PVT was identified in five (71.4%) patients, and three (42.8%) of these patients were submitted for splenectomy in the past. Studies report that the most frequent immediate complication of esophagogastric devascularization is PVT, with an occurrence rate of 52.3%.19 Postoperative PVT after splenectomy is a possible, but unusual, complication. However, because many patients remain asymptomatic, the true incidence of PVT may be underestimated. In studies where routine postoperative ultrasonography was done after splenectomy, the incidence of TPV ranged from 6.3 to 10.0%.20

In humans, portal deprivation, resulting from portacaval shunt or PVT, has been observed to induce a wide spectrum of liver nodules, including benign liver tumors, such as focal nodular hyperplasia and liver cell adenoma, and malignant tumors, such as HCC and hepatoblastoma, in addition to fibrosis and arterial proliferation in the portal space. The underlying mechanism of these changes remains unclear.21

Clinical studies in Egypt showed that 70-90% of patients with chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, or HCC are co-infected with schistosomiasis and HCV.1–5 It was suggested that the combination of chronic schistosomiasis caused by S. mansoni and HBV or HCV may cause a higher risk of HCC due to the increased viral load in co-infected patients, leading to higher inflammatory activity and more advanced disease state.1,2,4,5,15

Patients with S. mansoni infection tend to retain HBV and HCV for longer periods than those not infected with S. mansoni.21 In those with hepatosplenomegaly, the cell-mediated immune response was shown to be markedly depressed. Schistosoma infection affects the immune response in two ways to prolong the carrier state of the virus. Anti-idiotype antibodies produced in patients with chronic schistosomiasis can downregulate specific immune responses and suppress nonspecific immune responses.21,22

In addition, studies with mice and humans have shown that S. mansoni egg antigens can modify subpopulations of thymus helper cells, with an upregulation of helper T cell subtype 2 activity and the cytokines involved and with downregulation of helper T cell subtype 1 activity and cytokines, interleukin-2, and interferon δ as well as cytotoxic CD8+ T cells.3,4,15,21 Therefore, co-infected (S. mansoni infection and HBV or HCV) patients are at higher risk for early deterioration of liver function, the development of cirrhosis, and rapid progression towards end-stage liver disease and even HCC.20,21,23 In our sample, there were four (57.1%) patients with immunity by contact for HBV. The possible influence of this result on the disease course of these patients is unknown.

A recent experimental study evaluated the role of S. mansoni infection in enhancing and aggravating the carcinogenic effect of diethylnitrosamine, a carcinogenic substance. S. mansoni infection failed to initiate any dysplastic changes.5 Regarding the possible association between S. mansoni infection and HCC, studies have indicated that schistosomiasis may act as an additional factor, accelerating the injury related to other agents, such as HBV and HCV.1–5,22–24

There are some limitations of our study. This retrospective analysis of records was performed at a single institution, which did not allow us to generalize these data to the general population. The center is a reference unity for the treatment of HCC, and, thus, most cases were referred after the diagnosis of HCC, and biopsies were directed to the focal lesions with an aim of HCC diagnosis. The clinical history and epidemiological features associated with imaging changes and preserved liver function allowed for the diagnosis of schistosomiasis in most cases. However, it is possible that there may be, in addition to the infection with S. mansoni, some degree of chronic liver disease related to vascular changes, in particular chronic portal vein thrombosis and/or absence of ligation of the left gastric vein in splenectomized. The sample had few patients, and four (57.1%) of them had immunity by contact for HBV and its meaning is uncertain.

Conclusions

It remains unclear if S. mansoni infection alone has carcinogenic potential. The available literature indicates that S. Mansoni, in the presence of HBV and HCV infections, likely acts as a cofactor for the hepatic lesion and potentiates injury.

Abbreviations

- AFP

α-fetoprotein

- BCLC

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

- ECOG-PST

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status

- HBc

HBVcore

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- RFA

radiofrequency ablation

- TACE

transarterial chemoembolization

- PVT

portal vein thrombosis

- UGB

upper gastrointestinal bleeding

References

- 1.Khurana S, Dubey ML, Malla N. Association of parasitic infections and cancers. Indian J med Microbiol. 2005;23:74–79. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.16044. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.16044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdel-Rahim AY. Parasitic infections and hepatic neoplasia. Dig Dis. 2001;19:288–291. doi: 10.1159/000050695. doi: 10.1159/000050695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaker Y, Samy N, Asshour E. Hepatobiliary schistosomiasis. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2014;2:212–216. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2014.00018. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2014.00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palumbo E. Association between schistosomiasis and cancer - a review. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2007;15:145–148. doi: 10.1097/01.idc.0000269904.90155.ce. [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Tonsy MM, Husseain HM, Helal TE, Tawfik RA, Koriem KM, Hussein HM. Schistosoma mansoni infection: Is it a risk factor for development of hepatocellular carcinoma? Acta Trop. 2013;128:542–547. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2013.07.024. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2013.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brazilian Ministry of Health. Plano integrado de ações estratégicas de eliminação da hanseníase, filariose, esquistossomose e oncocercose como problema de saúde pública, tracoma como causa de cegueira e controle das geohelmintíases: plano de ação 2011–2015. 2012. Brazilian Ministry of Health, Brasília.

- 7.Davis A. Schistosomiasis. In: Cook G, editor. Manson’s Tropical Diseases. 20th ed. London: WB Saunders; 1996. pp. 1413–1456. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020–1022. doi: 10.1002/hep.24199. doi: 10.1002/hep.24199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cillo U, Vitale A, Grigoletto F, Farinati F, Brolese A, Zanus G, et al. Prospective validation of the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging system. J Hepatol. 2006;44:723–731. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.12.015. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paranaguá-Vezozzo DC, Ono SK, Alvarado-Mora MV, Farias AQ, Cunha-Silva M, França JI, et al. Epidemiology of HCC in Brazil: incidence and risk factors in a ten year-cohort. Ann Hepatol. 2014;4:386–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kakizoe Y. The influence of Schistosoma mansoni infection on carcinogenesis of mouse livers initiated by N-2-fluorenylacetamide. Kurume Med. 1985;32:169–178. doi: 10.2739/kurumemedj.32.169. doi: 10.2739/kurumemedj.32.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abe K, Kagei N, Teramura Y, Ejima H. Hepatocellular carcinoma associated with chronic Schistosoma mansoni infection in a chimpanzee. J Med Primatol. 1993;22:237–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hams E, Aviello G, Fallon PG. The Schistosoma granuloma: friend or foe? Front Immunol. 2013;4:89. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00089. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martins-Melo FR, Pinheiro MC, Ramos AN, Jr, Alencar CH, Bezerra FS, Heukelbach J. Trends in schistosomiasis-related mortality in Brazil, 2000–2011. Int J Parasitol. 2014;44:1055–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2014.07.009. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2014.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gentile JM, Gentile GJ. Implications for the involvement of the immune system in parasite-associated cancers. Mutat Res. 1994;305:315–320. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(94)90251-8. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(94)90251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evangelista-Neto J, Pereira FF, França ST, Amaral FJ, Brandt CT, Fonseca-Neto OCL, et al. Splenectomy and gastric vein ligature in hepatosplenic schistosomiais:effects upon esophageal variceal pressure and endoscopic risk factors of esophageal variceal bleeding. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2012;25:41–48. doi: 10.1590/s0102-67202012000100010. doi: 10.1590/S0102-67202012000100010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Batista-Neto J, Tognetti LB, Ribeiro LT, Balvani MC, Muritiba T, Alves EEC. Evolutional profile of the esophageal varices after splenectomy associated with ligation of the left gastric vein and sclerotherapy in schistosomal portal hypertension. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2013;26:49–53. doi: 10.1590/s0102-67202013000100011. doi: 10.1590/S0102-67202013000100011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andrade ZA. Schistosomiasis and liver fibrosis. Parasite Immunol. 2009;31:656–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2009.01157.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2009.01157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Makdissi FF, Herman P, Machado MAC, Pugliese V, D’Albuquerque LAC, Saad WA. Portal vein thrombosis after esophagogastric devascularization and splenectomy in schistosomiasis patients: What is the real importance? Arq Gastroenterol. 2009;46:50–56. doi: 10.1590/s0004-28032009000100014. doi: 10.1590/S0004-28032009000100014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhandarkar DS, Katara AN, Mittal G, Shah R, Udwadia TE. Prevention and Management of Complications of Laparoscopic Splenectomy. Indian J Surg. 2011;73:324–330. doi: 10.1007/s12262-011-0331-5. doi: 10.1007/s12262-011-0331-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guérin F, Wagner M, Liné A, Zappa M, Fasseu M, Paradis V, et al. Hepatic proliferation and angiogenesis markers are increased after portal deprivation in rats: a study of molecular, histological and radiological changes. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0125493. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125493. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stickland GT. Liver disease in Egypt: hepatitis C superseded schistosomiasis as result of iatrogenic and biological factors. Hepatology. 2006;43:915–922. doi: 10.1002/hep.21173. doi: 10.1002/hep.21173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bahgat MM. Interaction between the neglected tropical disease human schistosomiasis and HCV infection in Egypt: a puzzling relationship. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2014;2:134–141. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2013.00028. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2013.00028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamal S, Madwar M, Bianchi L, Tawil AE, Fawzy R, Peters T, et al. Clinical virological and histopathological features: long-term follow-up in patients with chronic hepatitis C co-infected with S. mansoni. Liver. 2000;20:281–289. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2000.020004281.x. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2000.020004281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]