Abstract

Purpose

Progressively deteriorating visual field is a characteristic feature of primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG), and the biomechanics of optic nerve head (ONH) is believed to be important in its onset. We used porohyperelasticity to model the complex porous behavior of ocular tissues to better understand the effect variations in ocular material properties can have on ONH biomechanics.

Methods

An axisymmetric model of the human eye was constructed to parametrically study how changes in the permeabilities of retina-Bruch's-choroid complex (kRBC), sclera (ksclera), uveoscleral pathway (kUVSC), and trabecular meshwork (kTM) as well as how changes in the stiffness of the lamina cribrosa (LC) and sclera affect IOP, LC strains, and translaminar interstitial pressure gradients (TLIPG).

Results

Decreasing kRBC from 5×10−12m/s to 5×10−13m/s increased IOP and LC strains by 17%, and TLIPG by 21%. LC strains increased by 13% and 9% when the scleral and LC moduli were decreased by 48% and 50%, respectively.

Conclusions

In addition to the trabecular meshwork and uveoscleral pathway, the retina-Bruch's-choroid complex had an important effect on IOP, LC strains, and TLIPG. Changes in kRBC and scleral modulus resulted in nonlinear changes in the IOP, and LC strains especially at the lowest kTM and kUVSC. This study demonstrates that porohyperelastic modeling provides a novel method for computationally studying the biomechanical environment of the ONH. Porohyperelastic simulations of ocular tissues may help provide further insight into the complex biomechanical environment of posterior ocular tissues in POAG.

Keywords: ocular biomechanics, permeability, finite element analysis, porohyperelasticity, choroid, translaminar pressure gradients

Introduction

A progressively degenerative disease, primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) is the second leading cause of blindness worldwide (1). Vision loss in glaucoma occurs from the death of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) which could result from aging in the eye, genetic predisposition of an individual, or an elevated intraocular pressure (IOP). A compromised drainage of the aqueous humour leads to a chronically elevated IOP (above the ~15mmHg in a healthy eye) thereby increasing the risk of POAG (2). IOP-lowering treatment has been shown to reduce the visual field loss, and continues to be the dominant treatment methodology for glaucoma (3). It must be mentioned, however, that there are normotensive eyes that are glaucomatous and hypertensive eyes that are non-glaucomatous (4). Previous research has shown that axonal density in the optic nerve head (ONH) is greatly reduced due to elevated IOP (5). As such, the biomechanics of the tissues in and around the ONH (e.g. lamina cribrosa, peripapillary sclera, sclera etc.), in response to IOP variations, have received significant research attention.

Previous research speculated that changes in the material properties of ocular tissues could affect ONH biomechanics and may contribute to POAG (6-9). Since experimental testing of ocular tissues can be challenging, computational models were used to study their effect on ONH biomechanics (6-8, 10, 11). These studies have used single phase (solid) constitutive models that account for finite deformations, anisotropy, viscoelasticity, and an underlying microstructural organization (7, 8, 12-17). However, these models did not include the porous nature of ocular tissues (which was established experimentally (18-22)), or features like translaminar pressure gradients, which have been shown to be important in governing orthograde axonal transport (3, 23, 24). Additionally, it is known that there is a passive flow of water from the aqueous to the vitreous chamber (25) which, in turn, is a “highly hydrated connective tissue” (26). We believe that modeling ocular tissues as a combination of solid and fluid behaviors will capture their complex behavior and could help better understand the factors leading to POAG.

Towards this aim, we present a porohyperelastic (PHE) finite element model (FEM) of the human eye and study the effects of permeabilities of the trabecular meshwork (TM), uveoscleral pathway (UVSC), choroid, and sclera, as well as the moduli of the lamina cribrosa (LC) and sclera on IOP, strains in the LC, and translaminar interstitial pressure gradient (TLIPG). We believe PHE-FEMs can provide a new perspective on the events leading to the death of RGCs and POAG progression, while also being useful for future models of local drug delivery in the eye.

Methods

Theory of porohyperelasticity and material constitutive laws

The following sections summarize the kinematics and governing laws of the theory of porohyperelasticity

Kinematics

The displacement of a material point from a point ‘Xi’ to ‘xi’ is given as ui = xi – Xi and the spatial rate of deformation is given by , where velocity . The material is considered to be a combination of a fluid and a solid component, thus .

Conservation of momentum

The equations for the static equilibrium under no body forces are , where ‘σij’ is the total Cauchy stress in the body.

Conservation of mass

The law of conservation of mass for the pore fluid and the solid is given by . ‘Dfr’ refers to the relative fluid velocity strain.

Effective stress principle and PHE constitutive law

The individual solid and the fluid components are incompressible whereas the material as a whole is compressible. The drained effective strain energy density function (Weff) and the hydraulic permeability (kij) are two material properties that need to be assigned in the simulation. The strain energy density function defines the “effective stress” in the solid which contributes to the total stress as: where, ; here, Se, the second Piola-Kirchhoff stress, is derived from Weff as , ‘Fij’ is the deformation tensor and J = det(F). The Cauchy stress is related to Se as . For this work, we assumed a neo-Hookean constitutive model for the drained effective strain energy density (27) for all tissues; , for which the model parameters (C10,D1) are defined in terms of the shear and bulk moduli of the tissue respectively, as , . Due to a lack of data, the shear and bulk moduli were calculated using the Young's modulus and Poisson's ratio of each individual tissue (see Table 1 for the values used and their sources).

Table 1.

Baseline material properties and references used in this study.

| Tissue | E(Pa) | v | C10 (Pa) | D1(Pa−1) | Source | k (m/s) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choroid | 6e5 | 0.49 | 100671.14# | 2e-7# | (38, 50) | 5e-12 to 5e-14 | Parametric study variable |

| Cornea | 2.9e5 | 0.42 | 51056.34+ | 3.31e-6+ | (51, 52) | 2.2e-11# | (53) |

| Iris | 9.6e3 | 0.48 | 1621.6# | 2.5e-5# | (54) | 1.1e-12* | Assumed same as lens |

| Lamina cribrosa | 2.6e5 | 0.49 | 43624.2+ (from 2.3e4 to 6.3e4) | 4.6e-7+ (from 3.2e-7 to 8.6e-7) | (8) | 8.3e-11* | Interpolated based on sclera permeability. Parametric study variable |

| Lens, ciliary body | 8.2e5 | 0.47 | 139455.8# | 4.4e-7# | (55, 56) | 1.1e-12# | (57) Ciliary body properties assumed to be same as lens |

| Zonule | 3.5e5 | 0.47 | 59523.1* | 1e-6* | (58) | 1e-6* | Permeability assumed |

| Post laminar | 3e4 | 0.49 | 5033.6# | 4e-6# | (8, 38) | 1.01e-11# | Assumed incompressible. Permeability assumed to be same as choroid |

| Sclera | 2.35e6 | 0.47 | 399659.9+ (from 1.9e5 to 6.12e5) | 1.5e-7+ (from 1e-7 to 3.27e-7) | (38, 52) | 6.37e-11# (from 2.09 e-11 to 10.65e-11) | (19) Parametric study variable |

| Trabecular meshwork | 4e3 | 0.35 | 740.74# | 450e-6# | (59, 60) | 8e-8 to 8e-10 | Parametric study variable |

| Uveoscleral pathway | 4e3 | 0.47 | 740.74# | 450e-6# | (59, 60) | 6e-11 to 6e-9 | Parametric study variable |

| Aqueous humour | 4.2e4 | 0.49 | 7047+ | 2.9e-6+ | (61) | 1e-3* | Assumed |

| Vitreous humour | 4.2e4 | 0.49 | 7047* | 2.9e-6* | Assumed same as aqueous humour | 1e-3* | Assumed same as aqueous humour |

C10 and D1 are the neo-Hookean constants derived from the Young's modulus and Poisson's ratio data in the cited references. ‘k’ is hydraulic permeability.

refers to assumed values and

refers to values used in previous computational studies.

refers to values determined experimentally in previous studies. Parameters that were varied as part of the parametric study are shown in boldface and italicized. Ranges upon which the parameters were varied are in parantheses.

Darcy's law of convection for pore fluid

The saturating fluid was assumed to be water; its flow through the porous solid is governed by Darcy's law which relates the inherent nature of the porous medium, its permeability, and a gradient in the pore pressure across the medium to the relative velocity: . The permeability (k) is assumed here to be isotropic kij = kδij. The apparent fluid velocity, (vfr) is expressed in terms of the absolute velocities of fluid and solid media and the reference porosity (n0) of the solid which is defined as the ratio of the volume of the fluid to the volume of the material, . The current porosity is given by n = 1 – J−1(1 – n0), and is related to the void ratio as . A constant permeability, and deformation-independent void ratio have been assumed for all the simulations in this study. We utilized PHE theory as has been implemented in ABAQUS® (27) and as we have used in several prior publications (28-32).

Ocular Geometry

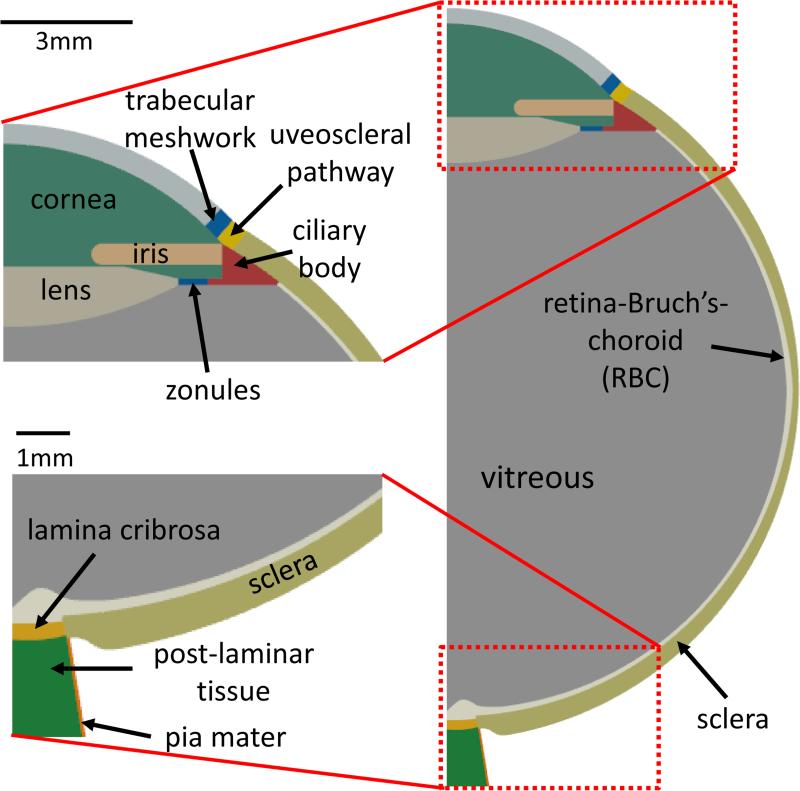

An axisymmetric model of the human eye was constructed containing the major structural components of the eye based on the descriptions given by Oyster, 1999 (33) and Sigal et al., 2004 (8) (see Figure 1). The region labeled “TM” was 0.5mm wide and represents all tissues along the conventional (or primary) outflow pathway up to the episcleral veins, and the region “RBC” (retina-Bruch's-choroid) encompasses all tissues between the vitreous and sclera (e.g., retina, Bruch's membrane, choroidal capillaries etc.). The UVSC (0.48mm wide) was modeled as an interface of the cornea and the sclera. The eye had an internal radius of 12mm, and was 25mm long from the tip of the cornea to the end of the LC. The iris was 3mm long with a constant 0.5mm thickness. The lens thickness decreased from 2mm on the axis of symmetry to 0.16mm where it attaches to the zonule (0.16mm thick and 0.75mm long). The ciliary body was 1mm in height and shared an edge with the sclera. The LC thickness varied from 0.3mm (symmetry axis) to 0.28mm (scleral insertion). The RBC complex was a 0.2mm thin lining along the interior of the sclera. The post-laminar tissue was modeled 1.9mm in height and 1.3mm wide at the base, and the pia mater, a 0.07mm thin layer, surrounds the post-laminar tissue.

Figure 1.

Model geometry: Used for the parametric finite element study. TOP-LEFT - Anterior segment. BOTTOM-LEFT - Posterior segment. The geometry of posterior ocular tissues was taken from (11), while that of the anterior segment was taken from (33). See ‘Ocular Geometry’ in the Methods section for a detailed description.

Boundary Conditions

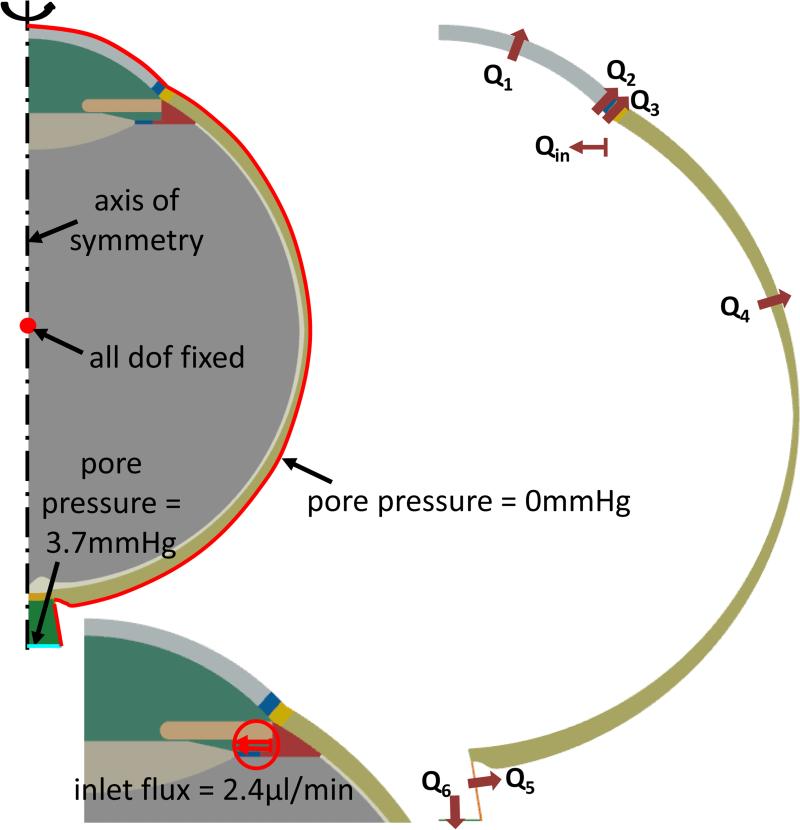

There were four boundary conditions imposed on each model in the parametric study (see Figure 2). First, the center of the vitreous chamber was fixed in all displacement degrees of freedom to remove rigid body motions. Second, the pore pressures at the exterior corneal, and episcleral surfaces were set to zero. Third, the cerebrospinal fluid pressure (CSFp) was held at 3.7 mmHg (24). Lastly, an aqueous influx of 2.4μL/min (the driving boundary condition for all simulations) was applied on the ciliary body (34).

Figure 2.

A) Boundary conditions and applied loads for the PHE model (shown in thick red lines). Nodes for each boundary condition are colored red. Axisymmetric FE model (the dashed line indicates the axis of rotation) pinned at midsection of the vitreous humour with a pore pressure = 0mmHg on the corneal surface, sclera shell, and at the posterior edge of the optic nerve. BOTTOM-LEFT: Surface load (flux) mimicking fluid exit from ciliary body. B) Schematic of the surfaces where flow occurs. ‘Qin’ refers to inflow near the ciliary body, and ‘Qi’ (i=1,2,..6) represents all possible outflow pathways. At steady-state, Qin = ΣQi.

Material Properties and Parametric Studies

Parametric studies were performed by varying the permeabilities of the RBC (kRBC), sclera (ksclera), UVSC (kUVSC), and TM (kTM), as well as the elastic moduli of the sclera and LC. Table 1 lists the baseline values and the ranges upon which the parameters were varied. Although many of the material properties were taken from previous studies, the properties of some tissues were assumed on a physiological basis due to a lack of data. For example, the aqueous and vitreous humours were assumed to have high permeabilities to mimic a water-like behavior. Likewise, the LC permeability was calculated by linearly interpolating from scleral permeability using the porosities of the LC and sclera (35, 36). For the solid components of the TM and UVSC regions, the average of the solid material property values of the cornea and sclera was used.

Since the permeabilities of TM, UVSC, and RBC were not reported in literature, the following process was used to establish their baseline values. Previous literature has shown that in humans 85-90% of the aqueous humour drainage occurs through the TM (33), and the UVSC accounts for <10% of the outflow (10, 37) at normal IOPs. Using baseline properties for all other tissues, the permeabilities of TM, UVSC, and RBC were varied across several orders of magnitude in a parametric fashion (starting from 1×10−3 m/s and decreasing progressively) to achieve 87% and 9% of total outflows through TM and UVSC respectively (see Figure 2 for the outflow locations used for this calculation), while maintaining an IOP of 15mmHg. This exercise resulted in kTM =7.9×10−9 m/s, kUVSC =5.6×10−10 m/s, and kRBC =5×10−13 m/s. For these permeabilities, the average outflow velocity through the cornea was found to be 17 μm/hr. In comparison, Ethier et al. have reported that the average outflow velocity of aqueous humour through the cornea is 20 μm/hr (10).

To parametrically study their effect on the IOP, LC strain, and TLIPGs, the permeabilities of TM, UVSC, and RBC were varied through 1 order of magnitude about their “baseline” values determined using the process described above. This variation in kTM and kUVSC resulted in high IOPs (greater than 100mmHg in some cases). Since such high pressures are not physiologically observed, the results presented here are restricted to kTM and kUVSC domains for which the IOP ranged from 5 to 45mmHg. We believe this spans a wide range of physiologically possible scenarios of hypotensive, normal, and hypertensive eyes. Varying the widths of the TM and UVSC by ± 10% did not show any effect on IOP, LC strain, and TLIPG and as such were not included in the parametric study.

In addition to varying the above permeabilities, the LC and scleral stiffnesses were varied over the standard deviations reported for both tissues in the literature, see Table 1 (38). The terms “stiffness” and “modulus” are used interchangeably in the following text. Results for all of the above studies included pore pressures in the aqueous/vitreous chambers, pore pressure gradients across the LC, and strains in the LC. The minus sign in the plots for LC axial strains (in the direction parallel to the axis of symmetry) denotes compression; larger negative values correspond to higher axial strains. Radial strains are strains in the direction orthogonal to the direction of the axis of rotation.

Results

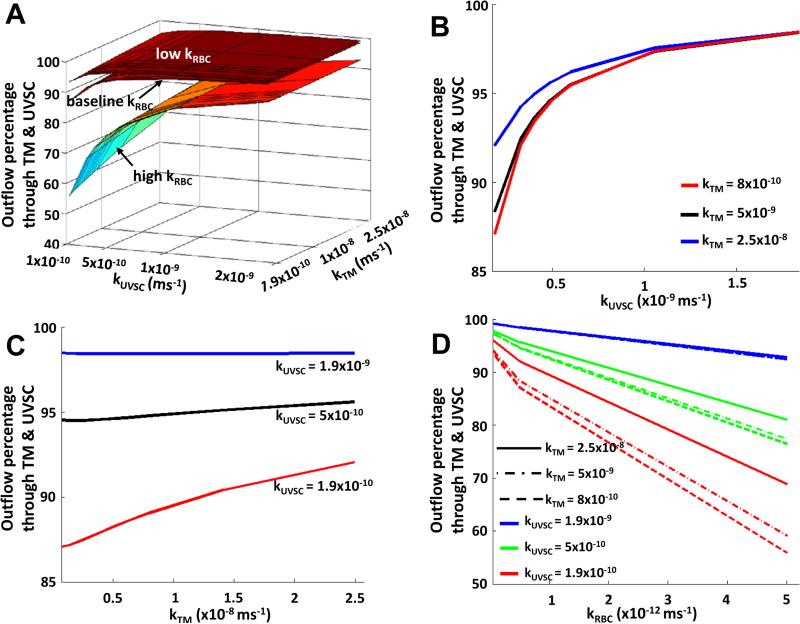

Shown in Figure 3 is the variation of the aqueous outflow through the TM and UVSC with changes in the permeabilities of TM, UVSC, and RBC. Increasing TM permeability from its baseline value resulted in a prominent nonlinear effect at lower UVSC and RBC permeabilities, which changed to a linear (nearly constant) variation at higher UVSC permeability (Figure 3C). The UVSC permeability showed a similar effect on the outflow as TM permeability, with a greater influence at lower TM permeability (see Figure 3B). It is interesting to note that RBC permeability (like UVSC permeability) showed a nonlinear effect on the total outflow from TM and UVSC, with varying degree of nonlinearity for different kTM - kUVSC combinations (Figure 3D). In comparison, increasing or decreasing scleral permeability by 67% from its baseline altered the outflow by less than 1% (figures not included).

Figure 3.

Increasing TM and UVSC outflow permeabilities reduced the percentage of total outflow differently through the anterior segment (A). TM and UVSC had a nonlinear effect on the total outflow (B, C). Increased RBC permeability increased outflow percentage through the posterior segment (D). The outflow percentages from the anterior region were greatly reduced at low anterior permeabilities. Baseline kTM = 7.9×10−9m/s and baseline kUVSC = 5.6×10−10m/s. Data in (A, B, C) are plotted for the baseline RBC permeability.

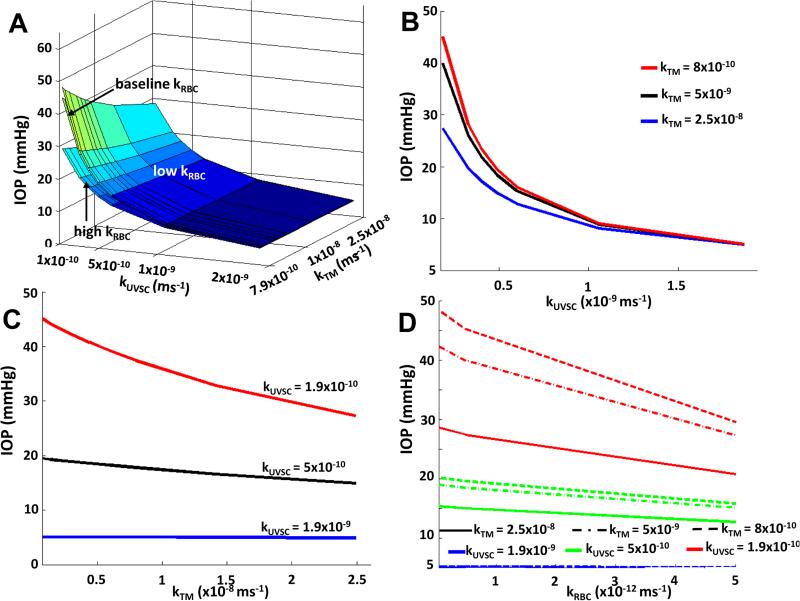

As with the total percent outflow from the TM and UVSC, the IOP showed a nonlinear variation with TM permeability at lower UVSC and RBC permeabilities (see Figure 4). The greatest drop in IOP due to TM (a decrease of 24%) occurred when its permeability was increased from its lower limit to its baseline value (for the lowest UVSC permeability, see Figure 4C). In the case of UVSC and RBC permeabilities, the greatest drops in IOP were found to be 87% and 35% respectively (for the lowest TM permeability, see Figure 4B, 4D). Decreasing scleral permeability from its baseline changed the IOP by only 0.2mmHg (figures not shown). This variation was linear, and similar for all kTM - kUVSC combinations.

Figure 4.

Variation of IOP with TM and UVSC permeabilities (A, B, C). A lower RBC permeability increased the IOP for all kTM - kUVSC combinations (D). Baseline kTM = 7.9×10−9m/s and baseline kUVSC = 5.6×10−10m/s. Data in (A, B, C) are plotted for the baseline RBC permeability.

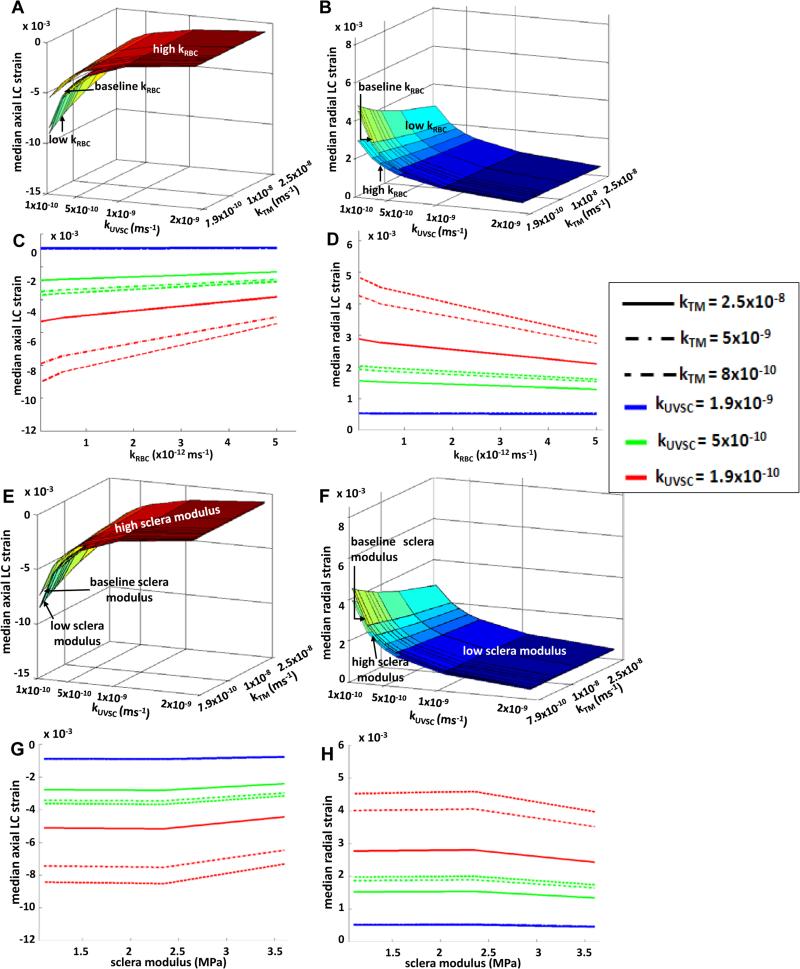

The median axial strain in the LC decreased by 17% with increased RBC permeability (see Figure 5A, 5C) with the highest median axial LC strain of 9×10−3 seen at low TM, UVSC, and RBC permeabilities. As with axial strains, median radial strain in the LC followed a nonlinear variation with increasing RBC permeability (see Figure 5B, 5D). At higher TM and UVSC permeabilities, the median radial LC strain remained fairly unchanged with changing RBC permeability; however, at lower TM and UVSC permeabilities, it decreased by 17% with increasing RBC permeability. It should be noted that the permeability variations affected LC strains not directly but via changes in IOP. LC modulus variation resulted in relatively linear changes in its strains. Increasing LC modulus decreased the axial strains by 12% (figures not shown). Although increasing scleral modulus showed a similar decrease in the median axial LC strain as LC modulus (see Figure 5E, 5G), the variation was slightly nonlinear. Radial strains followed a similar behavior: increasing the LC modulus decreased the median radial LC strain by 9% (figures not shown), and decreased by 12.5% for a high scleral modulus (see Figure 5F, 5H).

Figure 5.

Effect of RBC permeability on average axial LC strains (A, C), and average radial LC strains (B, D). Higher strains were observed at lower outflow permeability in the anterior region (kTM and kUVSC combined). Nonlinear variation in the LC strains was observed due to changes in RBC permeability. It is important to note that the effect of RBC permeability on LC strains is indirect. Increases in IOP due to RBC permeability (see Figure 4) increase the LC strains. Linear variations in scleral modulus resulted in nonlinear variations in the LC axial strains (E, G) LC radial strains (F, H). The variations were more noticeable at lower outflow permeabilities in the anterior segment. Baseline kTM = 7.9×10−9m/s and baseline kUVSC = 5.6×10−10m/s. See Table 1 for modulus values.

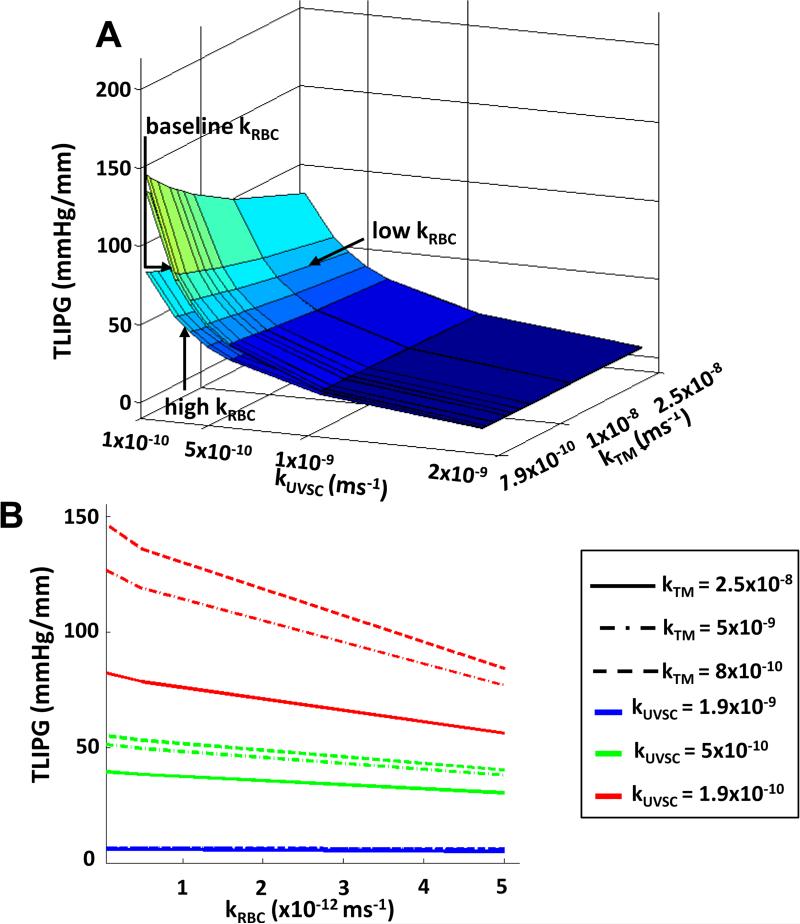

TLIPG, like IOP, was found to increase with decreasing TM, UVSC, and RBC permeabilities (see Figure 6). At baseline values for all tissues, the TLIPG was found to increase from 43 mmHg/mm to 143 mmHg/mm when TM, UVSC, and RBC permeabilities were decreased to their lower limits. Decreasing kRBC from its upper limit to its baseline increased the TLIPG by 21%. Scleral permeability and stiffness, as well as LC stiffness were found to have little effect on TLIPGs.

Figure 6.

Decreasing RBC permeability increased the TLIPG for all kTM - kUVSC combinations. Similar to IOP and LC strains, the TLIPGs varied nonlinearly with RBC permeability. Baseline kTM = 7.9×10−9m/s and baseline kUVSC = 5.6×10−10m/s.

Discussion

Summary of Results

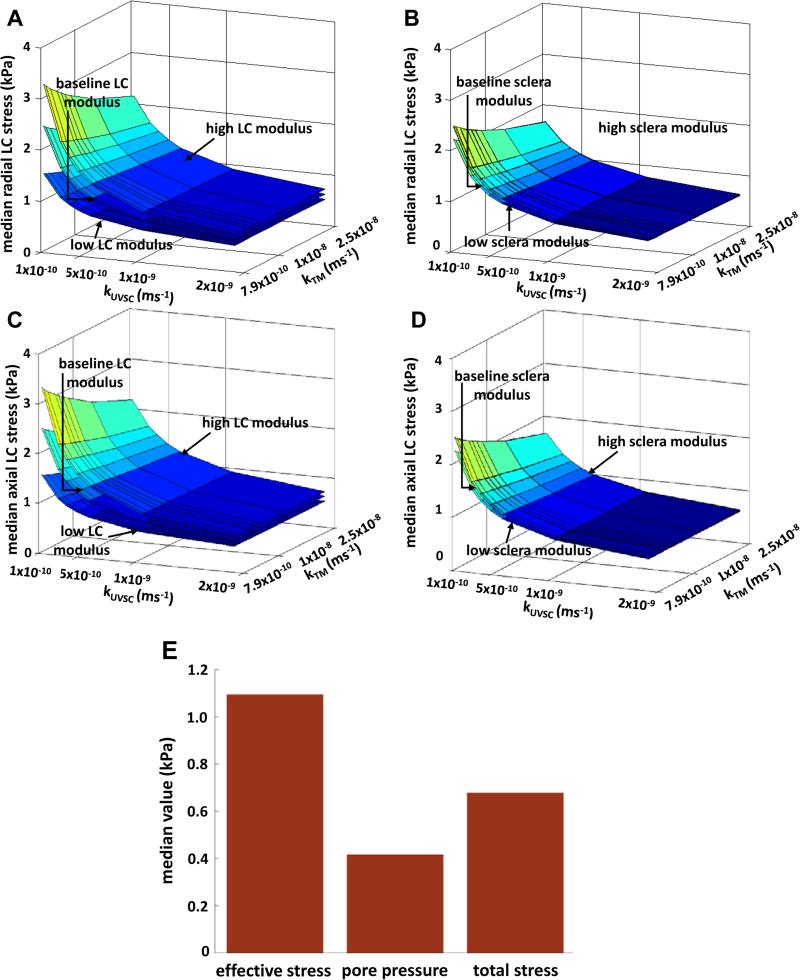

A parametric study on the permeabilities of the TM, UVSC, retina-Bruch's-choroid complex, and sclera along with the moduli of LC and sclera using a porohyperleastic finite element model is presented here. From our results, the total percent outflow from TM and UVSC, and IOP varied nonlinearly at lower kTM, kUVSC, and kRBC. This variation changed to linear as the permeabilities of the three regions increased (see Figures 3,4). In comparison, variations in the IOP and outflow through anterior segment due to changes in scleral permeability were minimal. There were similar trends observed in the LC strains, TLIPGs, and IOP due to variations in kRBC, kUVSC, and kTM (see Figures 4-8), reemphasizing a correlation between them. Leading to these correlations is the variation in the aqueous humour outflow through TM, UVSC, cornea, and sclera (see Figure 3). On the other hand, changing the scleral stiffness resulted in greater, and nonlinear increase in LC strains compared to changing LC stiffness (see Figures 6,7). Overall, the highest IOP (45mmHg), LC strains (9×10−3 and 5.3×10−3), and TLIPGs (143mmHg/mm) were found to occur at low TM, UVSC, and RBC permeabilities, as expected.

Figure 7.

Variation of axial and radial effective stresses with LC modulus (A, C), and sclera modulus (B,D). LC modulus resulted in a linear variation unlike scleral modulus. (E) Illustration of the effective stress principle for LC stresses using baseline properties for all regions of the eye. See Table 1 for modulus values.

Relation to Previous Work

While current FEM models of ocular tissues have included the effects of large deformations, anisotropy, and microstructural organization (7, 8, 12-17), we are not yet aware of models that incorporate the effects of a fully saturated and finite deformation porous continuum. As such, prior models have demonstrated the importance of the microstructure and mechanical properties of ocular tissues in governing the biomechanical environment of the ONH, but have lacked information on interstitial tissue fluid pressures and their gradients.

From our results, the highest LC strain occurred at low kTM, kUVSC, and kRBC, and was found to be 9×10−3 in the axial direction and 5.3×10−3 in the radial direction (at IOP = 45mmHg). These values are lower in magnitude compared than those reported previously (~5×10−2 and ~10×10−2 respectively at IOP=50mmHg (8)). This difference in the magnitudes of strain at baseline kRBC is likely due to the contribution of the pore fluid pressure which, as shown in Figure 9A-E, takes a portion of the total stress in the LC and thus reduces the effective stress (and therefore strain) in the tissue. Despite this difference, our results show that scleral modulus could have a protective influence on the LC.

With regards to the pore pressure gradients across the LC, at baseline permeabilities for all tissues, a TLIPG of approximately 39mmHg/mm occurred at an IOP of 15mmHg, compared to ~23mmHg/mm reported by Morgan et al. (24). Note that in our simulations the prelaminar tissue was assumed to have the same baseline properties as the retina-Bruch's-choroid complex which could have resulted in the disagreement in the TLIPG values. Overall, despite this difference in the values, our study supports Morgan et al.'s conclusion that TLIPG has a strong correlation with the IOP-CSF pressure difference (24). With regards to TM and UVSC permeabilities, it is known that the TM constitutes 80-90% of the total outflow, while the UVSC accounts for 10-15% (33). Based on our preliminary study to determine the baseline value of kTM (see Material Properties and Parametric Studies section), a reasonable value for its permeability was approximately 7.9×10−9 m/s. While this value lies outside the range reported previously (from 2.2 ×10−8 m/s to 1.1×10−7 m/s in (37)) for juxtacanalicular tissue, it is close to the lower limit.

As for kUVSC, there is no prior study, to our knowledge, that has quantified the outflow permeability of this pathway. We believe that, given the criteria used for our preliminary study, our baseline value of UVSC permeability is a good starting point for a more rigorous experimental validation in future. The baseline value of RBC permeability (kRBC = 5×10−13 m/s) from our preliminary study is lower than Fisher's value of 7.82 ×10−12 m/s for Bruch's membrane in a 70yr old eye (39), and closer to the Bruch's membrane permeability of 1×10−12m/s (the lower limit of the range) reported by Starita et al (40). Previous studies have shown that there exists a wide, age-dependent variability in not only the material properties (18, 40-43) but also in the thicknesses of the tissues in the retina-Bruch's-choroid region (44, 45), which could significantly decrease the permeability of these tissues (46). A disproportionate incidence of POAG across gender and race/ethnic groups (39) introduces yet another factor to be considered while evaluating the effect of ocular tissue material properties. Given the strong correlation between IOP and LC biomechanical parameters seen in our results, and the significant influence the permeabilities of the surrounding tissues can have on them, characterizing outflow permeabilities of these ocular tissues in glaucomatous, hypertensive, and normal eyes (for different age, gender, and race/ethnic groups) could be important in understanding the progression of POAG. We believe that the permeability values of kTM, kUVSC, and kRBC determined in our study will provide a comparison for future experimental efforts in this direction.

Interpretation and clinical implications

Our results showed that IOP, LC strains, and TLIPG were affected the most by small changes in kRBC (after kTM and kUVSC) followed by ksclera, scleral stiffness, and lastly, LC stiffness. This effect of the variation in the permeabilities of TM, UVSC, and RBC is more at lower ends of their ranges than at the upper ends. Interestingly, our results suggest that a similar reduction in LC axial strains can be achieved by either increasing the RBC permeability or increasing the scleral modulus. In addition, higher TLIPGs, which can disrupt axonal transport in peripheral nerves (42) and can be critical in the mechanism that leads to RGC death (23), were seen at low outflow permeabilities of RBC in our simulations. This suggests that for the range of permeabilities studied here, the retina-Bruch's-choroid complex (as defined herein) may play a role in governing the biomechanics of the ONH and may contribute to the incidence of POAG. As such, the RBC complex may potentially be a candidate tissue to target for treatment of ocular hypertension. Although computational in nature, these findings could be further explored to study the role IOP plays in the inhibition of axonal transport. Such information could have important clinical implications since it can expand the ability of complex computational models (like the one presented here) to study the efficacy of delivering IOP-lowering and anti-glaucoma drugs.

Limitations of the study

The current study includes several limitations. Although the geometry closely resembles the human eye, it is still an oversimplification (axisymmetric geometry, simplified lens and iris, simplification of outflow pathways). Ongoing work in our laboratory is focused on generating more realistic ocular geometries to address this issue. It was also assumed that there exists a small amount of anterior-to-posterior flow (~3%, at baseline permeabilities) which effectively equilibrates the IOP in the anterior and posterior chambers. Based on previous studies (25, 26, 47, 48), we believe that this assumption is reasonable. Another limitation of this study is that while some of the material properties were taken from previous experimental studies (using samples from different species and ages), others were assumed based on physiological intuition. This could vary the magnitudes of the effects these tissues can have on the LC strains and IOPs especially since it was shown previously that the geometry and properties of ocular tissues from different species can influence the biomechanical environment in the eye (49). Lastly, we have assumed constant permeabilities for all the regions but in reality they may vary with deformation. With all of these limitations in mind, we encourage the reader to interpret the reported results with care.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study that presents a PHE model of the human eye in which strains, IOPs, and TLIPGs are simultaneously and parametrically studied. We believe that one of the advantages of a PHE approach is that a fluid influx condition can be imposed that allows, in addition to mechanical strains, IOP and pressure gradients to be computational outputs. This is not possible in the solid continuum models in which the outputs are limited to displacements, strains, and stresses. While it is currently unknown if tissue permeability and porosity play a central role in ONH biomechanics, we strongly believe that it is an important feature to be considered that adds a new dimension to the understanding of the pathobiology of POAG. We hope that our observations will motivate future studies to better characterize the material properties of ocular tissues and the biomechanical environment in the human eye.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this work was provided by the NIH grant 1R01EY020890 to JPVG, partial support by the University of Arizona TRIF Fellowship Program to AA, and is based on work partially supported by Award No. KUK-C1-013-04, made by King Abdullah University of Science and Technology.

References

- 1.Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2006;90:262–267. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.081224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sommer A. Ocular hypertension and normal-tension glaucoma time for banishment and burial. Arch Opthalmology. 2011;129:785–787. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang K, Zhang L, Weinreb RN. Ophthalmic drug discovery novel targets and mechanisms for retinal diseases and glaucoma. Nature Reviews. 2012;11:541–559. doi: 10.1038/nrd3745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koz OG, Turkcu MF, Yarangumeli A, Kural G. Normotensive glaucoma and risk factors in normotensive eyes with pseudoexfoliation syndrome. J Glaucoma. 2009;18:684–688. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31819c4311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baltan S, Inman DM, Danilov CA, Morrison RS, Calkins DJ, Horner PJ. Metabolic vulnerability disposes retinal ganglion cell axon to dysfunction in a model of glaucomatous degeneration. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30:5644–5652. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5956-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coudrillier B, Tian J, Alexander S, Myers KM, Quigley HA, Nguyen TD. Biomechanics of the Human Posterior Sclera: Age- and Glaucoma-Related Changes Measured Using Inflation Testing. IOVS. 2012;53:1714–1728. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Downs JC, Suh JK, Thomas KA, Bellezza AJ, Burgoyne CF, Hart RT. Viscoelastic characterisation of peripapillary sclera:material properties by quadrant in rabbit and mokey eyes. J Biomech Eng. 2003;125:124–131. doi: 10.1115/1.1536930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sigal IA, Flanagan JG, Tertinegg I, Ethier CR. Finite element modeling of optic nerve head biomechanics. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:4378–4387. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan D, McPheeters S, Johnson G, Utzinger U, Vande Geest JP. Microstructural differences in the human posterior sclera as a function of age and race. IOVS. 2011;52:821–829. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ethier CR, Johnson M, Ruberti J. Ocular biomechanics and biotransport. Ann Rev Biomed Eng. 2004;6:249–273. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.6.040803.140055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sigal IA, Flanagan JG, Tertinegg I, Ethier CR. Reconstruction of human optic nerve heads for finite element modeling. Technol Health Care. 2005;13:313–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Girard M JA, Downs CJ, Bottlang M, Burgoyne CF, Suh J-K F. Peripapillary and posterior scleral mechanics, Part II - experimental and inverse finite element characterization. J Biomech Eng. 2009;131 doi: 10.1115/1.3113683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grytz R, Fazio MA, Girard MJ, Libertiaux V, Bruno L, Gardiner S, Girkin CA, J DC. Material properties of the posterior human sclera. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2014;29:602–617. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2013.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grytz R, Meschke G, Jonas JB. The collagen fibril architecture in the lamina cribrosa and peripapillary sclera predicted by a computational remodeling approach. Biomech Mode Mechanobiol. 2011;10:371–382. doi: 10.1007/s10237-010-0240-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grytz R, Meschke G. Constitutive modeling of crimped collagen fibrils in soft tissues. Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2009;2:522–533. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roberts MD, Sigal IA, Liang Y, Burgoyne CF, Downs CJ. Changes in the Biomechanical Response of the Optic Nerve Head in Early Experimental Glaucoma. IOVS. 2010;51:5675–5684. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sigal IA, Flanagan JG, Ethier CR. Factors influencing optic nerve head biomechanics. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:4189–4199. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fisher RF. The influence of age on some ocular basement membranes. Eye. 1987;1:184–189. doi: 10.1038/eye.1987.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jackson TL, Hussain A, Hodgetts A. Human sclera hydraulic conductivity: age-related changes, topographical variation, and potential scleral outflow facility. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:4942–4946. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson TL, Hussain A, Morley AM. Scleral hydraulic conductivity and macromolecular diffusion in patients with uveal effusion syndrome. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:5033–5040. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson M, Erickson k. Mechanisms and routes of aqueous humor drainage. In: Albert DM, Jakobiec FA, editors. Principles and Practices of Ophthalmology. W B Saunders Co.; Philadelphia: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Overby D, Ruberti J, Gong H, Freddo TF, Jonhnson M. Specific hydraulic conductivity of corneal stroma as seen by quick-freeze/deep-etch. J Biomech Eng. 2001;123:154–161. doi: 10.1115/1.1351888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Band LR, Hall LC, Richardson G, Jensen OE, Siggers JH, Foss A JE. Intracellular flow in optic nerve axons: A mechanics for cell death in glaucoma. IOVS. 2009;50:3750–3758. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morgan WH, Yu DY, Alder VA. The correlation between cerebrospinal fluid pressure and retrolaminar tissue pressure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:1419–1428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maurice DM. Flow of water between aqueous and vitreous compartments in the rabbit eye. American Physiology Society. 1987;252:F104–F108. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1987.252.1.F104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fatt I. Hydraulic conductivity of the vitreous gel. IOVS. 1977;16:565–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Systèmes Dassualt. Systèmes D, editor. ABAQUS. 2011;611 Documentation. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ashton J, Ayyalasomayajula A, Simon BR, Vande Geest JP. Wall stress reduction in abdominal aortic aneurysms as a result of polymeric endoaortic paving. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2011;39:1680–1689. doi: 10.1007/s10439-011-0271-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ayyalasomayajula A, Vande Geest JP, Simon BR. Porohyperelastic finite element modeling of abdominal arotic aneurysm. J Biomech Eng. 2010;132:1–8. doi: 10.1115/1.4002370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harper JL, Simon BR, Vande Geest JP. A one-dimensional mixed porohyperelastic transport swelling finite element model with growth. Journal of Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials. 2014;29:663–675. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2013.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simon BR, Kaufman MV, McAfee MA, Baldwin AL. Porohyperelastic finite element analysis of large arteries using ABAQUS. J Biomech Eng. 1998;120:296–298. doi: 10.1115/1.2798315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vande Geest JP, Simon BR, Rigby PH, Newberg TP. Coupled porohyperelastic mass transport (PHEXPT) finite element models for soft tissues using ABAQUS. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 2011;133 doi: 10.1115/1.4003489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oyster CW. The human Eye: Structure and Function. Sinauer Associates, Inc.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goel M, Picciani RG, Lee RK, Bhattacharya SK. Aqueous humor dynamics: A review. The Open Ophthalmology Journal. 2010;4:52–59. doi: 10.2174/1874364101004010052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kadam RS, Kompella UB. Influence of lipophilicity on drug partitioning into sclera, choroid-retinal pigment epithelium, retina, trabecular meshwork, and optic nerve. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;332:1107–1120. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.161570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 36.Yan D, Keyes JT, Vande Geest JP. Quantative measurement of pressure dependent laminar cribrosa microstructure in human eyes.. Summer Bioengineering Conference; Pennsylvania. 2011.2011. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson M. What controls aqueous humour outflow resistance? Exp Eye Res. 2006;82:545–557. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friberg TR, Lace JW. A comparison of the elastic properties of human choroid and sclera. Exp Eye Res. 1988;47:429–436. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(88)90053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rudnicka AR, Mt-Isa S, Owen CG, Cook DG, Ashby D. Variations in primary open-angle glaucoma prevalence by age, gender, and race: A Bayesian meta analysis. IOVS. 2006;47 doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Starita C, Hussain AA, Pagliarini S, Marshall J. Hydrodynamics of ageing Bruch's membrane: implications for macular disease. Experimental Eye Research. 1996;62:565–572. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Booij JC, Baas DC, Beisekeeva J, Gorgels TGMF, Bergen The dynamic nature of Bruch's membrane. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 2010;29:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moore DJ, Hussain AA, Marshall J. Age related variation in the hydraulic conductivity of Bruch's membrane. IOVS. 1995;36:1290–1297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Okubo A, Rosa RH, Bunce CV, Alexander RA, Fan JT, Bird AC, Luthert PJ. The relationships of age changes in retinal pigment epithelium and Bruch's membrane. IOVS. 1999;40:443–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chakraborty R, Read SA, Collins MJ. Diurnal Variations in Axial Length, Choroidal Thickness, Intraocular Pressure, and Ocular Biometrics. IOVS. 2011;52:5121–5129. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-7364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spraul CW, Lang GE, Grossniklaus HE. Morphometric analysis of the choroid, Bruch's membrane, and retinal pigment epithelium in eyes with age-related macular degeneration. IOVS. 1996;37:2724–2735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moore DJ, Clover GM. The Effect of Age on the Macromolecular Permeability of Human Bruch's Membrane. IOVS. 2001;42:2970–2975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davson H. The Eye. 2 ed Academic Press; New York: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fatt I, Hedbys B. Flow of water in the sclera. Exp Eye Res. 1970;10:243–249. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(70)80035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nauman EA, Sander EA, Downs JC, Hart RT, Burgoyne CF. Comparison of animal eye geometries and their impact on ocular biomechanics. ARVO. 2005 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woo SL, Kobayashi AS, Schlegel WA, Lawrence C. Nonlinear material properties of intact cornea and sclera. Exp Eye Res. 1972;14:29–39. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(72)90139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hamilton KE, Pye DC. Young's modulus in normal corneas and the effect on applanation tonometry. Optom Vis Sci. 2008;85:445–450. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181783a70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Uchio E, Ohno S, Kudoh J, Aoki K, Kisilewicz LT. Simulation model of an eyeball based on finite element analysis on a supercomputer. Clinical Science. 1999;83:1106–1111. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.10.1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Overby D, Ruberti J, Gong H, Freddo TF, Johnson M. Specific hydraulic conductivity of corneal stroma as seen by quick-freeze/deep-etch. J Biomech Eng. 2001;123:154–161. doi: 10.1115/1.1351888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heys J, Barocas VH. Mechanical characterization of the bovine iris. J Biomech. 1999;32:999–1003. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(99)00075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fisher RF. Elastic constants of the human lens capsule. J Physiology. 1969;201:1–19. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1969.sp008739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fisher RF, Wakely J. The elastic constants and ultrastructural organization of a basement membrane (lens capsule). Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1976;193:335–358. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1976.0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Johnson M, Erickson K. Mechanisms and routes of aqueous humor drainage. In: Albert DM, Jakobiec FA, editors. Principles and Practices of Opthalmology. W B Saunders Co.; Philadelphia: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weeber HA, van der Heijde GL. Internal deformation of the human crystalline lens during accommodation. Acta Ophthalmologica Scandinavica. 2007 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.01116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Avtar R, Srivastava R. Modelling aqueous humor outflow through trabecular meshwork. Applied Mathematics and Computation. 2007;189:734–745. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Last AJ, Pan T, Reilly CM, Keller K, Scott TS, Fautsch MP, Murphy CJ, Russell P. Elastic modulus determination of normal and glaucomatous human trabecular meshwork. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:2147–2152. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cirovic S, Bhola RM, Hose DR, Howard IC, Lawford PW, Parsons MA. A computational study of the optic nerve evulsion. IUTAM Preoceedings on Impact Biomechanics: From Fundamental Insights to Applications. 2005:469–476. 2005. [Google Scholar]