Introduction

Duel-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) has become a method of choice for assessing body composition because of its unique ability to conveniently and efficiently measure distinct body compartments: 1) total and regional fat mass (FM), 2) lean tissue mass (LTM), 3) bone mineral content (BMC), and 4) bone mineral density (BMD). The accuracy and reliability of DXA is generally accepted due to the series of validation studies that have consistently demonstrated highly significant relationships to animal carcass analysis of bone, LTM, and FM (pig, rat, and mouse) [1–4].

Since the development of DXA in the 1980s, improvements in the DXA’s capability and accuracy have been ongoing. Newer models have incorporated reduced scan times, more powerful X-rays, improved image quality, and more recently, the ability to accommodate larger patient sizes and co-morbid conditions. However, differences in DXA models (i.e., manufacturer, software version, type of scanning beam, and method of calibration) may affect results. Hence, it is imperative to compare data among instruments before data are combined from different instruments or software for research or clinical application. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to compare data from the GE-Lunar Prodigy DXA and the newer GE-Lunar iDXA for determining total and regional BMD, BMC, FM, LTM, total body mass (BM) and percent fat.

Methods

A total of 92 healthy adults 20 – 74 years of age was used in this study (Table 1). Sample population was 61% female (n = 56) and 39% male (n = 36). Ethnicity varied among the participants with Caucasian being the most frequently reported (73%), followed by African American (22%), Asian (4%), and Hispanic (1%). This study was approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board. All participants gave written informed consent. All women of child-bearing age completed a pregnancy test prior to participating.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| (n=92) | Mean ± SD | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 39.8 + 12.3 | 20 – 74 |

| Weight (kg) | 77.2 ± 17.1 | 45.0 – 125.5 |

| Height (cm) | 170.4 ± 10.1 | 143.0 – 194.3 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.5 ± 5.4 | 18.0 – 44.7 |

Height and weight were measured for each participant and recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm and 0.1 kg, respectively. Each participant was scanned consecutively on the iDXA (GE Healthcare, Madison, WI, USA) and Prodigy DXA (GE Healthcare, Madison, WI, USA). The iDXA total-body scans were analyzed using enCORE 2008 version 12.3 software, which determined an appropriate transverse speed based upon estimated subject thickness (thick > 25 cm; standard 16 – 25 cm; thin < 16 cm). Prodigy total-body scans were performed using enCORE 2002 version 6.10.029, which also determined an appropriate transverse speed based upon estimated subject thickness (thick >25 cm; standard 13–25 cm; thin < 13 cm). Scan modes (thick, standard, or thin) were automatically set via the software on both scanners. Scan times lasted approximately 5–10 minutes on both scanners. Total body measurements included analyses of the head.

Regional Analysis

All iDXA and Prodigy scan analyses were performed according to the manufacturer’s guidelines by the same individual using the GE Lunar enCORE softwares’ standard analysis modules. In addition to total-body composition, regional estimates were made for the arms, legs, and trunk. This was accomplished by manually adjusting cut positions for each region of interest (ROI). The individual cut lines and/or the individual region vertex points were adjusted by selecting the Move Vertex tool and using the mouse pointer to drag the line or point to the desired position. For the left and right arm ROIs, one cut passed through the arm sockets and separated the hands and arms from the body. For the left and right leg ROIs, a cut passed through the femoral neck to separate each from the pelvis, a second cut was made laterally to separate the leg from the forearm and hand, and a third cut was made medially between the left and right leg. The trunk ROI was isolated by a cut located directly above the pelvis, another located directly below the chin, and cuts made on the left and right side of the body, which separated the trunk from the left and right arms, respectively. Once the ROI’s were properly positioned, the results were calculated by selecting the “Results” icon.

Statistical analysis

Body composition measurements (BM, FM, LTM, BMC, bone area, and BMD) were compared between instruments using paired t-test (parametric) and Wilcoxon signed ranked tests (non-parametric test). To prevent higher probability of declaring false significance that arises due to multiple testing on the same dataset, adjusted p-values were calculated using the false discovery rate (FDR).[5] When significant differences were noted, t-tests were repeated to explore whether between instrument differences were influenced by gender and/or BMI (BMI </= 24.9). The coefficient of variation (CV) was calculated to describe measurement errors between iDXA and Prodigy. [6] The Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) provided the measure of technique variance. [7] The correlation coefficient between iDXA and Prodigy of all body composition measurements (BM, FM, LTM, BMC, bone area, and BMD) are also reported. Linear regression was used to determine relationships between iDXA and Prodigy, and the method of Bland and Altman [8] was used to assess agreement between the two instruments. Differences or associations were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS (Version 22.0, Armonk, NY).

Results

Comparison of total-body composition parameters measured by iDXA and Prodigy are provided in Table 2, and percent differences between the two instruments are provided in Table 3. Both the Paired t-tests and Wilcoxon signed ranked tests indicated that iDXA, relative to Prodigy, provided significantly lower estimations of total body BMD (difference = −2.1%), and BMC (−4.9%). The adjusted p-values with false discovery rate (FDR) provided similar results compared to individual tests. These differences remained within each gender and BMI subgroup (P<0.001). There were no significant differences between instruments in measures of bone area (−2.0%; P = 0.698), FM (3.0%; P = 0.942), LTM (0.3%; P = 0.914), BM (−0.1 %; P = 0.168), or percent fat (3.2%; P = 0.493).

Table 2.

Comparison of body composition parameters measured by iDXA and Prodigy (mean±SD).

| Region | Parameter | iDXA | Prodigy | P a | Pb | CV | ICC | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total bodyc | BMD (g/cm2) | 1.22 ± 0.15 | 1.25 ± 0.13 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.0825 | 0.75 | 0.001 |

| BMC (kg) | 2.8 ± 0.63 | 2.9 ± 0.67 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.1479 | 0.79 | 0.001 | |

| Bone Area | 2275.2 ± 303 | 2283.97 ± 331 | 0.698 | 0.363 | 0.0937 | 0.77 | 0.793 | |

| Fat mass (kg) | 24.5 ± 10.9 | 24.5 ± 11.9 | 0.942 | 0.748 | 0.0747 | 0.99 | 0.974 | |

| Lean tissue mass (kg) | 49.5 ± 10.5 | 49.5 ± 11.0 | 0.914 | 0.743 | 0.0598 | 0.96 | 0.974 | |

| Total body mass (kg) | 77.1 ± 17.0 | 77.2 ± 17.1 | 0.168 | 0.085 | 0.0217 | 0.99 | 0.22 | |

| Percent fat (%) | 31.1 ± 9.1 | 31.0 ± 10.7 | 0.493 | 0.425 | 0.0864 | 0.97 | 0.575 | |

|

| ||||||||

| Arms | BMD (g/cm2) | 0.79 ± 0.10 | 0.94 ± 0.12 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.0417 | 0.95 | 0.001 |

| BMC (kg) | 0.38 ± 0.10 | 0.41 ± 0.11 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.0488 | 0.99 | 0.001 | |

| Bone Area | 466.4 ± 78 | 367.65 ± 77.9 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.1160 | 0.80 | 0.001 | |

| Fat mass (kg) | 2.4 ± 1.1 | 2.3 ± 1.3 | 0.002 | <0.001 | 0.2050 | 0.93 | 0.003 | |

| Lean tissue mass (kg) | 5.7 ± 2.0 | 5.9 ± 2.0 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.2338 | 0.77 | 0.001 | |

| Percent fat (%) | 29.2 ± 10.6 | 26.7 ± 11.9 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.1342 | 0.95 | 0.001 | |

|

| ||||||||

| Legs | BMD (g/cm2) | 1.32 ± 0.17 | 1.39 ± 0.16 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.0251 | 0.98 | 0.001 |

| BMC (kg) | 1.05 ± 0.24 | 1.14 ± 0.25 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.0362 | 0.98 | 0.001 | |

| Bone Area | 786.7 ± 110 | 803.1 ± 115 | 0.018 | 0.019 | 0.0824 | 0.83 | 0.030 | |

| Fat mass (kg) | 9.0 ± 3.7 | 9.2 ± 4.3 | 0.104 | 0.387 | 0.1562 | 0.94 | 0.156 | |

| Lean tissue mass (kg) | 17.4 ± 4.1 | 16.8 ± 4.1 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.0814 | 0.94 | 0.001 | |

| Percent fat (%) | 32.9 ± 9.1 | 33.4 ± 11.2 | 0.061 | 0.123 | 0.0764 | 0.99 | 0.098 | |

|

| ||||||||

| Trunk | BMD (g/cm2) | 1.05 ± 0.14 | 0.99 ± 0.10 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.0463 | 0.98 | 0.001 |

| BMC (kg) | 0.85 ± 0.20 | 0.91 ± 0.24 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.0601 | 0.98 | 0.001 | |

| Bone Area | 792.9 ±115 | 896.2 ± 177 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.1648 | 0.61 | 0.001 | |

| Fat mass (kg) | 12.1 ± 6.8 | 12.2 ± 6.6 | 0.294 | 0.074 | 0.0959 | 0.98 | 0.363 | |

| Lean tissue mass (kg) | 22.9 ± 4.8 | 22.7 ± 5.2 | 0.974 | 0.988 | 0.0544 | 0.97 | 0.970 | |

| Percent fat (%) | 31.8 ± 11.1 | 32.2 ± 11.4 | 0.123 | 0.136 | 0.1069 | 0.95 | 0.172 | |

Comparisons made by paired t-tests

Comparisons made by Related samples Wilcoxon signed rank test

Total body parameters include the head in the estimate

CV = Coefficient of variation

ICC = Intraclass correlation coefficient

FDR = False discovery rate

Table 3.

Limits of agreement for total and regional body composition parameters measured by iDXA and Prodigy DXA.

| Region | Parameter | Difference (iDXA - Prodigy) | Percent Difference (%) | Limits of agreement (Difference ± 2SD) | r a | P a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total body | BMD (g/cm2) | −0.025 | −2.1 | − 0.084 – 0.036 | 0.525 | 0.001 |

| BMC (kg) | −0.151 | −4.9 | −0.460 – 0.164 | −0.155 | 0.158 | |

| Bone Area (cm2) | −8.734 | −2.0 | −4.220 – 4.268 | −0.142 | 0.171 | |

| FM (kg) | 0.013 | 3.0 | −3.514 – 3.486 | −0.627 | < 0.001 | |

| LTM (kg) | 0.005 | 0.3 | −4.220 – 4.268 | −0.064 | 0.550 | |

| BM (kg) | −0.126 | −0.1 | −1.950 – 1.702 | −0.056 | 0.614 | |

| Fat % | 0.162 | 3.2 | −4.258 – 4.582 | −0.237 | < 0.05 | |

|

| ||||||

| Arms | BMD (g/cm2) | −0.147 | −15.5 | −0.227 – −0.067 | −0.370 | < 0.001 |

| BMC (kg) | −0.020 | −6.1 | −0.078 – 0.026 | −0.429 | < 0.001 | |

| Bone Area (cm2) | 98.73 | 23.1 | −39.68 – 237.1 | 0.009 | 0.929 | |

| FM (kg) | −0.109 | 14.5 | −0.597 – 0.835 | −0.622 | <0.001 | |

| LTM (kg) | −0.228 | −3.9 | −0.941 – 0.479 | −0.068 | 0.550 | |

| Fat % | 2.342 | 15.7 | −4.004 – 8.872 | −0.409 | < 0.001 | |

|

| ||||||

| Legs | BMD (g/cm2) | −0.069 | −5.1 | −0.139 – 0.000 | 0.239 | <0.05 |

| BMC (kg) | −0.085 | −7.6 | −0.187 – 0.016 | − 0.083 | 0.439 | |

| Bone Area (cm2) | −16.48 | −2.0 | −149.0 – 116.1 | −0.080 | 0.441 | |

| FM (kg) | − 0.140 | 2.1 | −1.740 – 1.460 | −0.858 | < 0.001 | |

| LTM (kg) | 0.586 | 3.8 | −1.740 –1.460 | 0.044 | 0.678 | |

| Fat % | −0.558 | 1.0 | −6.074 – 4.958 | −0.766 | < 0.001 | |

|

| ||||||

| Trunk | BMD (g/cm2) | −0.065 | −6.4 | −0.033 – 1.158 | 0.727 | <0.001 |

| BMC (kg) | 0.057 | −4.9 | −0.315 – 0.201 | −0.157 | 0.142 | |

| Bone Area (cm2) | 103.3 | −12.2 | −382.0 – 175.3 | 0.621 | <0.001 | |

| FM (kg) | 0.227 | −1.1 | −2.717 – 2.763 | 0.180 | 0.091 | |

| LTM (kg) | −0.153 | 0.6 | −2.568 – 2.263 | −0147 | 0.170 | |

| Fat % | 0.151 | −0.5 | −6.153 – 5.189 | −0.113 | 0.290 | |

Correlation coefficient and level of significance for Bland-Altman plot. A simple correlation was performed between the Difference (iDXA − Prodigy) and the corresponding average ((iDXA + Prodigy)/2) for each estimate; a significant association indicates that the magnitude of the difference between instruments varies across the range of values in a linear manner (i.e., the slope of the line describing mean vs difference is significant).

Coefficient of variation was lower than 0.05 for total body mass, arms BMD, arms BMC, Legs BMD, legs BMC, and trunk BMC. The total body BMC, arms FM and LTM had the highest CV (Table 2). The total body BMD, total body BMC, total body bone area, trunk bone area, and arms lean tissue mass had an ICC less than 0.8 whereas the ICCs for all other measurements were higher than 0.95. Bone area correlation coefficients were ≥ .61 and all other correlation coefficients were greater than 0.95. All correlation coefficients were significant (P ≤ 0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlation matrix

| Prodigy DXA

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iDXA | BMD (g/cm2) | BMC (kg) | Bone Area | FM (kg) | LTM (kg) | BM (kg) | Fat % | ||

|

|

|||||||||

| Total body | BMD (g/cm2) | 0.979* | |||||||

| BMC (kg) | 0.965* | ||||||||

| Bone Area | 0.783* | ||||||||

| FM (kg) | 0.992* | ||||||||

| LTM (kg) | 0.981* | ||||||||

| BM (kg) | 0.991* | ||||||||

| Fat % | 0.986* | ||||||||

| Arms | BMD (g/cm2) | 0.952* | |||||||

| BMC (kg) | 0.980** | ||||||||

| Bone Area | 0.607* | ||||||||

| FM (kg) | 0.974** | ||||||||

| LTM (kg) | 0.985* | ||||||||

| Fat % | 0.962* | ||||||||

| Legs | BMD (g/cm2) | 0.975* | |||||||

| BMC (kg) | 0.972* | ||||||||

| Bone Area | 0.830* | ||||||||

| FM (kg) | 0.990* | ||||||||

| LTM (kg) | 0.964* | ||||||||

| Fat % | 0.97 | ||||||||

| Trunk | BMD (g/cm2) | 0.966* | |||||||

| BMC (kg) | 0.866* | ||||||||

| Bone Area | 0.621* | ||||||||

| FM (kg) | 0.900* | ||||||||

| LTM (kg) | 0.966* | ||||||||

| Fat % | 0.969* | ||||||||

Indicates significance at .05

p < 0.01

Regional body composition comparison measures by iDXA and Prodigy are presented in Table 5, and percent differences in Table 3. For the arms, iDXA, relative to Prodigy, provided significantly lower estimates of BMD (−15.5%; P < 0.001), BMC (−6.1%; P < .0.001) and LTM (−3.9%; P < 0.001) both in the whole sample and within the gender and BMI subgroups. In contrast, iDXA estimates of arm bone area (23.1%; P < .0.001), FM (14.5%; P < 0.01) and percent fat (15.7%; P < 0.001) were considerably higher relative to Prodigy. Between-group differences were found for FM, but not bone area or percent fat, based on gender and BMI such that, arm fat iDXA estimates, relative to Prodigy, were significantly higher in women (t = 3.708, P < 0.001) but not in men (t = 1.361, P = 0.182). Within BMI subgroups, higher arm FM iDXA estimates were noted in lean (t = 4.1543, P < 0.001) but not in overweight (t = 1.252, P = 0.216) participants. When arm FM was compared within gender and BMI subgroups concurrently, FM estimates remained greater for iDXA in females regardless of BMI (P < 0.001); however, in men, higher arm fat iDXA measurements, relative to Prodigy, persisted in lean (t = 5.312, P< 0.001), but not overweight (t = −0.24, P = 0.981), individuals.

Table 5.

Linear regression analysis for total and regional body composition parameters measured by iDXA and Prodigy.

| Region | Parameter | Regression equation | Line of Identity | Regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope (P) a | Intercept (P) a | r2 | P | SEE | |||

| Total body | BMD (g/cm2) | iDXA = 1.110PROD − 0.162 | <0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.959 | <0.001 | 0.03 |

| BMC (kg) | iDXA = 0.924PROD + 0.078 | <0.001 | 0.333 | 0.934 | <0.001 | 0.15 | |

| Bone Area (cm2) | iDXA = 0.715PROD + 639.5 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.613 | <0.001 | 189 | |

| FM (kg) | iDXA = 0.908PROD + 2.252 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.985 | <0.001 | 1.37 | |

| LTM (kg) | iDXA = 0.939PROD + 3.030 | <0.001 | 0.003 | 0.963 | <0.001 | 2.03 | |

| BM (kg) | iDXA = 0.996PROD + 0.227 | <0.001 | 0.542 | 0.998 | <0.001 | 0.76 | |

| Fat % | iDXA = 0.845PROD + 4.951 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.974 | <0.001 | 1.49 | |

|

| |||||||

| Arms | BMD (g/cm2) | iDXA = 0.829PROD + 0.015 | <0.001 | 0.621 | 0.893 | <0.001 | 0.04 |

| BMC (kg) | iDXA = 0.879PROD + 0.023 | <0.001 | 0.009 | 0.954 | <0.001 | 0.02 | |

| Bone Area (cm2) | iDXA = 0.613PROD + 241.2 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.370 | <0.001 | 62.6 | |

| FM (kg) | iDXA = 0.810PROD + 0.560 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.947 | <0.001 | 0.26 | |

| LTM (kg) | iDXA = 0.973PROD − 0.070 | <0.001 | 0.550 | 0.968 | <0.001 | 0.36 | |

| Fat % | iDXA = 0.857PROD + 6.300 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.933 | <0.001 | 2.78 | |

|

| |||||||

| Legs | BMD (g/cm2) | iDXA = 1.029PROD − 0.1110 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.958 | <0.001 | 0.03 |

| BMC (kg) | iDXA = 0.963PROD − 0.043 | <0.001 | 0.086 | 0.959 | <0.001 | 0.05 | |

| Bone Area (cm2) | iDXA = 0.793PROD + 149.7 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.698 | <0.001 | 62.1 | |

| FM (kg) | iDXA = 0.835PROD + 1.400 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.989 | <0.001 | 0.38 | |

| LTM (kg) | iDXA = 0.976PROD + 0.994 | <0.001 | 0.047 | 0.930 | <0.001 | 1.09 | |

| Fat % | iDXA = 0.800PROD + 6.132 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.969 | <0.001 | 1.61 | |

|

| |||||||

| Trunk | BMD (g/cm2) | iDXA = 1.280PROD − 0.211 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.925 | <0.001 | 0.37 |

| BMC (kg) | iDXA = 0.708PROD + 0.207 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.725 | <0.001 | 0.11 | |

| Bone Area (cm2) | iDXA = 0.404PROD + 431.0 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.385 | <0.001 | 91.1 | |

| FM (kg) | iDXA = 1.017PROD − 0.338 | <0.001 | 0.214 | 0.969 | <0.001 | 1.20 | |

| LTM (kg) | iDXA = 0.869PROD + 3.011 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.926 | <0.001 | 1.19 | |

| Fat % | iDXA = 0.943PROD + 1.379 | <0.001 | 0.118 | 0.940 | <0.001 | 2.73 | |

P for slope = 1, and intercept = 0.

In the legs, the iDXA yielded significantly lower estimates for BMD (−5.1%; P < 0.001), BMC (−7.6%, P < 0.001), and bone area (−2.0%; P < 0.05) and significantly higher estimates for LTM (3.8%, P < 0.001) in comparison to the Prodigy. BMD, BMC, and bone area iDXA measurements remained significantly lower regardless of gender; however, when examined by BMI subgroups, iDXA bone area estimates remained significantly lower in the lean (t = −2.303, P < 0.05), but not the overweight (t = −1.346, P = 0.184) participants. In addition, LTM iDXA estimates, relative to Prodigy, were higher only in women (t = 5.136, P< 0.001), regardless of BMI. No estimation differences were noted for FM and percent fat between iDXA and Prodigy in the leg.

In the trunk, iDXA yielded lower measures for BMD (−6.4%; P < 0.001) BMC (−4.9%, P < 0.001), and bone area (−12.2%; P < 0.001) in comparison to Prodigy, and the significantly reduced iDXA estimates were not influenced by gender or BMI. In addition, no differences were detected for FM, LTM, or percent fat.

Regression analysis indicated that slopes for all total-body measures (BMD, BMC, bone area, FM, LTM, BM, and percent fat) were significantly different from the line of identity (slope 1; Table 5). In addition, regression analyses also revealed that slopes between regional estimates of the arms, legs, and trunk (BMD, BMC, bone area, FM, LTM, and percent fat) were significantly different from the line of identity (P < 0.001). However, all total-body and regional measures obtained with the two instruments were significantly correlated (P < 0.05) (Table 4).

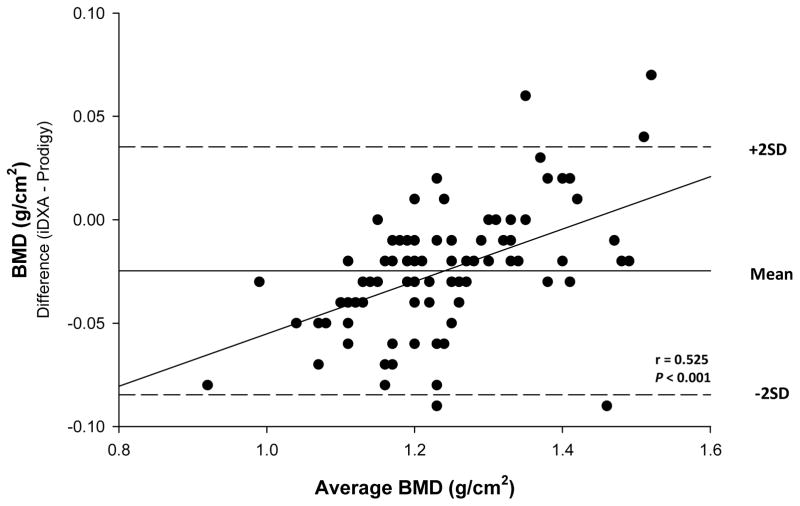

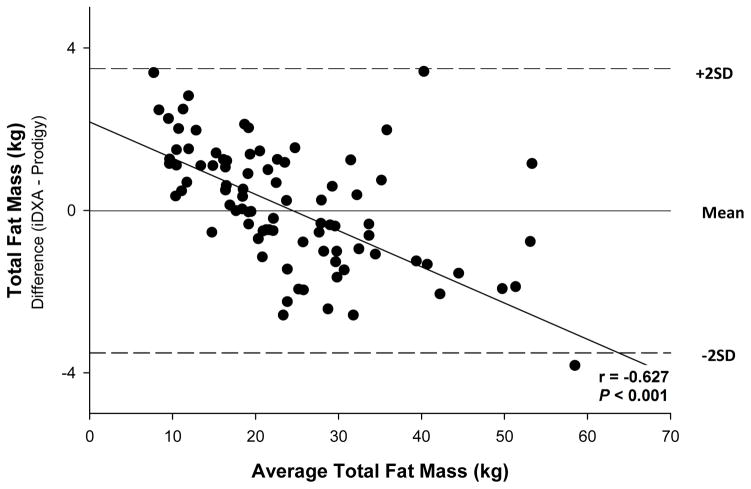

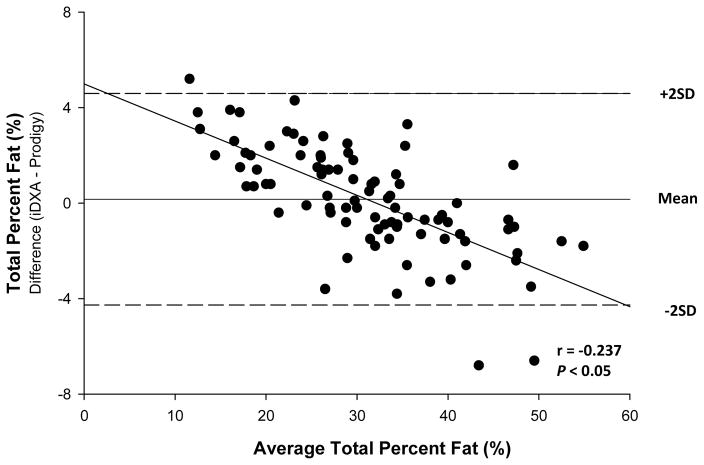

The procedure of Bland and Altman (Table 3) revealed that the over or underestimation of total or regional measures by iDXA relative to Prodigy varied with value. For total body measures, differences were detected in BMD (r = 0.525, P < 0.001) (Figure 1), FM (r = −0.627, P < 0.001) (Figure 2), and percent fat (r = −0.237, P < 0.05) (Figure 3). For total BMD, the underestimation by iDXA was most evident in participants with higher BMD values. For total FM and percent fat, overestimation was observed primarily in more obese participants. No estimation differences were detected for total body BMC, bone area, LTM or BM. Regionally, Bland and Altman analyses revealed significant and consistent underestimation for BMD in the arms (r = 0.370, p < 0.001), legs (r = 0.239, p < 0.05), and trunk (r = 0.727; P < 0.001), and the underestimations were noted such that participants with higher BMD estimates displayed a greater discrepancy. Arm BMC differences (r = −0.429, P < 0.001) were also observed such that participants with higher BMC measures showed a larger discrepancy. No other regional BMC estimation differences were observed. Bone area differences were noted in the trunk only such that data tended to be underestimated in individuals with higher bone area estimates (r = 0.621; P < 0.001). Arm (r = −0.622, P < 0.001) and leg (r = −0.858, P < 0.001) FM differences were noted such that data were underestimated in participants with the highest arm and leg FM estimates. Percent fat differences were detected in both the arms (r = −0.409, P < 0.001) and the legs (r = −0.766, P < 0.001). In the arms, percent fat overestimation was noted such that participants with lower estimates of percent fat displayed greater discrepancy. In the legs, percent fat underestimation was detected such that greater discrepancies were noted among participants with the highest percent fat estimates. FM or percent fat estimation differences were not detected in the trunk. In addition, no LTM estimation variance was observed among the arms, legs, or trunk. All outliers were within ± three standard deviations from the mean difference between the two DXA machines.

Figure 1. Bland-Altman Plot for total body BMD.

Figure 2. Bland-Altman Plot for total body fat mass.

Figure 3. Bland-Altman Plot for total body percent fat.

Discussion

It is imperative that investigators who conduct longitudinal studies and those who need to merge or compare data collected using different DXA instruments and/or software versions ensure that the two methods yield comparable results. When differences between devices or software versions are detected, cross-calibration equations are often needed to maintain data validity so that accurate comparisons can be made. This study compared total body and regional BMD, BMC, bone area, FM, LTM, and percent fat of GE Lunar iDXA (enCORE 2008 version 12.3) and GE Prodigy (enCORE 2002 version 6.10.029) systems and developed regression equations that may be used to translate Prodigy measurements to iDXA estimates.

In this study, we found that significant differences by iDXA, relative to Prodigy, exist for measurements of total body and regional BMD and BMC and regional only differences for bone area (Table 2). Differences in regional BMD, leg and trunk BMC and leg bone area were relatively small and not likely to be clinically significant; however, differences in arm BMD and arm and trunk bone area were substantial (15.5%; 23.1%, and 12.2%, respectively). Further, such consistent differences, regardless of magnitude, will affect the ability to combine or compare data between instruments for both clinical and research purposes.

Although soft tissue estimates did not differ with instrument at the whole-body level, several differences were noted at the regional level. iDXA estimates of lean tissue mass were significantly lower in the arms and higher in the legs. In the arm, underestimation of iDXA, in comparison to Prodigy, remained significant even when participants were examined within gender and BMI subgroups. Dissimilarities in leg LTM estimates varied by gender, but not BMI, with significant differences observed only in women. Although the reason for this gender difference is not clear, it may relate to the lower LTM in women vs men, or to the greater leg fat in women vs men, which may affect the ability of the instrument to discriminate fat and lean mass. Alternatively arm and leg LTM differences among women, but not men, could be the result of sampling bias as there were significantly more women, in comparison to men, who completed the study.

Regional fat mass and percent fat estimates from iDXA were greater, relative to Prodigy, only in the arms. FM, but not percent fat, was influenced by both gender and BMI, such that greater arm FM with iDXA was observed in both lean and overweight women, but only within lean men. In general, men, in comparison to women, have greater quantities of LTM and lower fat. It is possible that, in larger men with greater muscle, differences between instruments in X-ray penetration or image resolution are less apparent.

All total and regional estimates were significantly correlated and tended to differ by less than 5%. However, some discrepancies were much more significant, particularly in the arm. For example, iDXA estimates of arm FM were greater in comparison to Prodigy estimates (0.1 kg, 14.5%). Differences between instruments in measures of both bone and soft tissue may derive from the use of different versions of software. The iDXA comes equipped with a greater number of detectors and enhanced resolution, which provides better differentiation of bone and soft tissue. Specifically, the enhanced bone resolution improves the skeletal edge detection and the local estimation of tissue composition above, below, and near the bone. Since the arm generally consists of a smaller surface area in comparison to the legs and trunk, the enhanced iDXA resolution (i.e., improved bone/soft tissue resolution) may be more evident in the arm. Other aspects of the software may have contributed to differences in measures between instruments. For example, the cut-off points used for determining the scanning speed differed with software. The Prodigy enCORE version 6.10.029 software’s three scan modes were Thin (<13 cm), Standard (13–25 cm), and Thick (>25 cm). The iDXA enCORE version 12.3 software’s three scan modes were Thin (< 16 cm), Standard (16–25 cm), and Thick (> 25 cm). Therefore, inherent differences in scanning speed selection may have contributed to the observed variability between instruments for total-body and regional estimates. Variability in regional estimates may result from inherent differences in ROI determination between software packages. In other studies, software differences have contributed to differences in measures, even when the instrument make/model did not differ. [9, 10]

Differences in instrumentation between the two DXA machines may also have contributed to discrepancies in the measurements. The iDXA includes an improved high-definition, narrow-angle fan beam with multi-view image reconstruction technology that was added to eliminate magnification errors. The iDXA also has a direct-to-digital detector with a staggered array that is intended to eliminate dead spots. These technology advancements allow for increased image resolution, particularly in the bone; facilitate more accurate identification of region-of-interest boundaries; and allow for more precise compartmental assessments.

Bland and Altman analyses indicated that the magnitude of the discrepancy between instruments varied across the range of values; i.e., differences were detected for several measures. In measures of the bone in total body (Figure 1), arm, legs, and trunk, discrepancies tended to be greater in persons with higher BMD measures. Estimation differences were also noted for FM (Figure 2) and percent fat in total body (Figure 3), arm, and leg measurements with the greatest variances between iDXA and Prodigy estimates noted among the most obese participants. Thus, when combining or comparing data from different instruments investigators and clinicians should be aware that discrepancies in measured values may be greater among more obese individuals and/or patients with greater bone density.

Conclusions

The results of this study demonstrated that small, but significant differences exist between iDXA and Prodigy for several total-body and regional estimates; that those differences may be influenced by gender and BMI; and that in some cases, differences were magnified at the higher end of the range. Thus, caution should be applied when combining or comparing total body and regional bone estimates, FM in the arms, and LTM and percent fat in the arms and the legs. Differences between other estimates were small, and may not affect results unless small differences are critical to interpreting study outcomes. Measures of total body FM and percent fat were similar between instruments, and all measurements between the two instruments were highly and significantly correlated. To our knowledge, this is the first investigation to compare the iDXA and Prodigy DXA with the reported software packages for assessment of total and regional body composition. Because of the sample size used, as well as the broad range in subject age and body size, these results should apply to a variety of study populations comprised of healthy adults.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by the UAB Department of Nutrition and Award Number P30DK056336 from the National Institute Of Diabetes And Digestive And Kidney Diseases. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute Of Diabetes And Digestive And Kidney Diseases or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Suster D, Leury BJ, Ostowska E, et al. Accuracy of dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), weight and P2 back fat to predict whole body and carcass composition in pigs within and across experiments. Livestock Production Science. 2003;84(3):231–242. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pintauro SJ, et al. Cross-calibration of fat and lean measurements by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry to pig carcass analysis in the pediatric body weight range. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1996;63(3):293–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/63.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen W, et al. Abdominal fat analyzed by DEXA scan reflects visceral body fat and improves the phenotype description and the assessment of metabolic risk in mice. American Journal of Physiology - Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2012;303(5):E635–E643. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00078.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerbaix M, et al. Visceral fat mass determination in rodent: validation of dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry and anthropometric techniques in fat and lean rats. Lipids in Health and Disease. 2010;9(1):140. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-9-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological) 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLaughlin SC, Aitchison TC, Macfarlane PW. The value of the coefficient of variation in assessing repeat variation in ECG measurements. European Heart Journal. 1998;19(2):342–351. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1997.0741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carver TE, Christou NV, Andersen RE. In vivo precision of the GE iDXA for the assessment of total body composition and fat distribution in severely obese patients. Obesity. 2013;21(7):1367–1369. doi: 10.1002/oby.20323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1(8476):307–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnston SL, et al. PIXImus DXA with Different Software Needs Individual Calibration to Accurately Predict Fat Mass. Obesity Research. 2005;13(9):1558–1565. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Loan MD, et al. Evaluation of body composition by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry and two different software packages. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27(4):587–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]