Abstract

The sexual behavior of individuals living with HIV determines the onward transmission of HIV. With the understanding that antiretroviral therapy (ART) prevents transmission of HIV, the sexual behaviors of the individuals not on ART with unsuppressed viral loads becomes of the greatest importance in elucidating transmission. We assessed the association between being on ART and sexual risk behavior among those living with HIV in a nationally representative population-based cross-sectional survey of households in South Africa that was conducted in 2012. Of 2,237 adults (aged 15–49) who tested HIV-seropositive, 667 (29.8%) had detectable antiretroviral drugs in their blood specimens. Among males, 77.7% of those on ART reported having had sex in the past year contrasted with 88.4% of those not on ART (p=0.001); among females, 72.2% of those on ART reported having had sex in the past year while 80.3% of those not on ART did (p<0.001). For males and females, the odds of reporting consistent condom use and condom use at last sex were statistically significantly higher for individuals on ART compared to those not on ART (Males: consistent condom use aOR=2.8, 95% CI=1.6–4.9, condom use at last sex aOR=2.6, 95% CI=1.5– 4.6; Females: consistent condom use aOR=2.3, 95% CI=1.7–3.1, condom use at last sex aOR=2.3, 95% CI=1.7–3.1), while there were no statistically significant differences in odds of reporting multiple sexual partners in the past year. In this nationally representative population-based survey of South African adults, we found evidence of less risky sexual risk behavior among people living with HIV on ART compared to those not on ART.

Keywords: Antiretroviral therapy, people living with HIV, South Africa, sexual behavior

INTRODUCTION

South Africa has been greatly impacted by the HIV epidemic, with an estimated HIV prevalence among individuals aged 15–49 of 18.8% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 17.5–20.3%) in 2012[1]. An estimated 6.4 million people were living with HIV infection in South Africa in 2012[1], making South Africa the country with the largest absolute number of people living with HIV worldwide and nearly one-sixth of the burden worldwide[2]. The government of South Africa has made a strong commitment to providing HIV counseling and testing (HCT) to all individuals, and provided HCT to approximately 9 million South Africans between April 2012 and March 2013[3]. Additionally, the South African government has greatly expanded access to antiretroviral treatment[4] including increasing coverage of antiretroviral therapy (ART) to an estimated over 2 million people in mid-2012[1]. While South Africa has made great strides to decrease the burden of HIV, there remains significant stigma around HIV and HIV remains a major public health problem.

The HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) 052 study clearly demonstrated the protective nature of ART on risk of HIV transmission, showing that HIV transmission between serodiscordant couples is reduced by 96% with early treatment of the seropositive partner[5]. The protective nature of ART on HIV transmission makes the sexual behaviors of individuals who are not on ART, who mostly have unsuppressed viral loads and are at increased risk of transmitting their virus, of the utmost importance to understand in order to implement effective positive prevention strategies.

The sexual behavior of individuals on ART is additionally of interest. People living with HIV who initiate ART often experience an improvement in general health and may have an accompanied increase in sexual activity[6]. Given that superinfection with novel strains, particularly with drug-resistant strains of HIV, can speed up disease progression and complicate the treatment of HIV[7], understanding the risk behavior of people both on and off ART is necessary, particularly in the context of increasingly earlier treatment guidelines[8]. Increased sexual risk taking among individuals both on and not on ART, mainly increases in unprotected sex acts and increased number of sexual partners, puts individuals at increased risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unplanned pregnancies. Additionally, adherence to ART becomes increasingly important, including as protection from superinfection, though previously adherence has been found to be inconsistent in South African populations[9,10].

While early studies from Western countries suggested that individuals on ART may have increased risk behavior[11–14], most literature published in South Africa[15–18] and other settings in sub-Saharan Africa[19–27] (including a meta-analysis published in 2012[28]) found either no significant difference in sexual risk behavior or a decrease in sexual risk behavior between individuals on ART compared to those who are not, while a few studies showed support for an increase in sexual risk behavior by individuals on ART[29–31]. This question has yet to be assessed on a nationally representative scale in South Africa.

We aimed to assess the association between being on ART and sexual risk behavior among people of reproductive age (age 15–49) living with HIV in a nationally representative sample from South Africa undertaken in 2012. We assessed the following among those who reported sexual activity in the past 12 months: consistency of condom use, condom use at last sex and multiple sexual partnerships, comparing those on and not on ART.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

The fourth South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence, and Behaviour Survey (SABSSM IV) was a cross-sectional survey conducted in 2012 among individuals of all ages in all provinces of South Africa. SABSSM IV was a multi-stage cluster sample survey of residential households within enumeration areas sampled by province, race group and locality type (urban/rural and formal/informal) as defined by the census in South Africa[32]. Institutionalized individuals (including individuals in educational institutions, military barracks, old-age homes, or hospitals) were excluded from the study. This analysis is restricted to individuals aged 15–49 living with HIV.

Interviewers administered questionnaires to participants that included demographics, sexual history (including partner history, consistency of condom use and condom use at last sex), HIV testing history and risk perception, history of sexually transmitted infections, male circumcision, contraceptive use, and alcohol use, amongst others. All youth and adults who participated provided either written or verbal consent, including parent/guardian informed consent for youth under 18 years of age and youth verbal assent to have a blood specimen taken.

Laboratory Measures

Dried blood spot (DBS) specimens were collected from each participant who assented or consented using finger prick. Samples were tested for HIV using an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) (Vironostika HIV Uni-Form II plus O, Biomeriux, Boxtel, The Netherlands), and samples that tested positive were retested using a second EIA (Advia Centaur XP, Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics, Tarrytown, NJ, USA). Any samples with discordant results on the first two EIAs were tested with a third EIA (Roche Elecys 2010 HIV Combi, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Samples that tested positive for HIV-1 antibodies were tested for the presence of antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled with tandem mass spectrometry. Zidovudine, Nevirapine, Efavirenz, Lopinavir, Atazanavir, and Darunavir were detected using an Applied Biosystems API 4000 tandem mass spectrometer. The limit of detection was set to 0.2 micrograms/ml.

Statistical Analysis

We report socio-demographics of participants living with HIV by ART status stratified by sex, and test for differences between groups by ART status using the Pearson chi-square test of independence, in STATA 12 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX). To assess the association between ART status and sexual behavior outcomes (consistency of condom use with most recent partner, condom use at last sex, and multiple sexual partnerships), again stratified by sex, we used simple and multiple logistic regression for each outcome variable. Variables were included in multiple logistic regression analysis based on our literature review, and our final models adjusted for age category, race, income in the past month, locality type, partner type, education and alcohol use, as well as disclosure of HIV status to partner and alternative contraceptive method for condom use outcomes. Consistency of condom use was dichotomized to indicate “always” compared to “less than always” use.

RESULTS

Of 2,237 adults between the ages of 15 and 49 who tested HIV-seropositive, 667 (29.8%) had detectable ART in their blood specimens. Table I shows demographic characteristics of respondents living with HIV on and not on ART, stratified by gender. Among both males and females, the majority of the individuals on ART were older than those who were not on ART (median age 38 and 35 vs 32 and 30 for males and females, respectively). Fewer participants on ART had a regular sexual partner than those not on ART (among males: 69.0% of those on ART and 79.8% of those not on ART; among females: 66.6% of those on ART and 74.0% of those not on ART). A slightly higher proportion of males and females on ART had received any income in the past month compared to those not on ART (69.7% vs 61.4% among males, 59.0% vs 54.6% among females). The distribution of males on ART was different by locality type (more in rural informal areas were on ART: 32.1% vs 22.6%; and less often men in rural formal areas were on ART: 12.8% vs 18.9%), while among females, no locality differences were seen by ART.

Table I.

Demographic characteristics by ART status stratified by sex among South Africans living with HIV, 2012

| Males | Females | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not on ART (N= 509) | On ART (N=156) | Not on ART (N=1061) | On ART (N=511) | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Age | ||||||||

| Median | 32 | 38 | 30 | 35 | ||||

| 15–24 | 84 | 16.5 | 9 | 5.8 | 252 | 23.8 | 54 | 10.6 |

| 25–34 | 236 | 46.4 | 47 | 30.1 | 460 | 43.4 | 183 | 35.8 |

| 35–49 | 189 | 37.1 | 100 | 64.1 | 349 | 32.9 | 274 | 53.6 |

|

| ||||||||

| Race | ||||||||

| African | 453 | 89.0 | 137 | 87.8 | 982 | 92.6 | 474 | 92.8 |

| Non-African | 56 | 11.0 | 19 | 12.2 | 79 | 7.5 | 37 | 7.2 |

|

| ||||||||

| Partner Statusa | ||||||||

| No regular partner (Single, divorced, etc) | 102 | 20.2 | 48 | 31.0 | 273 | 26.0 | 170 | 33.4 |

| Regular partner (Married, cohabitating, going steady) | 403 | 79.8 | 107 | 69.0 | 776 | 74.0 | 339 | 66.6 |

|

| ||||||||

| Received any income in last montha | 309 | 61.4 | 108 | 69.7 | 569 | 54.6 | 298 | 59.0 |

|

| ||||||||

| Locality Type | ||||||||

| Urban Formal | 198 | 38.9 | 50 | 32.1 | 351 | 33.1 | 162 | 31.7 |

| Urban Informal | 100 | 19.7 | 36 | 23.1 | 218 | 20.6 | 112 | 21.9 |

| Rural Informal | 115 | 22.6 | 50 | 32.1 | 371 | 35.0 | 182 | 35.6 |

| Rural Formal | 96 | 18.9 | 20 | 12.8 | 121 | 11.4 | 55 | 10.8 |

Totals within demographic characteristics do not add to overall total due to missing data

Table II shows HIV risk behavior reported by participants living with HIV by ART status, stratified by sex. Individuals on ART were less likely to report having been sexually active in the past year than those who were not on ART (77.7% compared to 88.4% among males, and 72.2% compared to 80.3% among females). Higher proportions of respondents on ART reported that they used condoms consistently and at last sex compared to those not on ART (consistent condom use: 57.4% vs 34.9% among males, and 53.7% vs 33.5% among females; condom use at last sex: 73.2% vs 45.3% among males, and 65.5% vs 44.5% among females). The proportion of respondents reporting multiple partnerships in the past 12 months was slightly lower among those on ART compared to those not on ART (14.9% vs 20.9% among males; 5.1% vs 7.7% among females). Those respondents on ART reported less binge drinking (28.8% vs 34.1% among males; 8.0% vs 11.1% among females), and more respondents on ART reported no alcohol use in the past 12 months (58.8% vs 46.7% among males; 87.0% vs 79.4% among females). A greater proportion of those on ART disclosed their status to their sexual partner (62.3% vs 46.3% among males and 60.3% vs 53.9% among females). Of those who were not on ART, 52.1% of women and 39.6% of men had received an HIV test and their results in the past 12 months. Significantly more individuals on ART reported healthcare services use in the past 6 months compared to those not on ART (71.0% and 71.5% compared to 41.0% and 50.2%, for males and females, respectively).

Table II.

HIV risk behaviors by ART status stratified by sex among South Africans living with HIV, 2012

| Males | Females | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Not on ART (N= 509) | On ART (N=156) | Chi-squared statistic (df) {p-value} | Not on ART (N=1061) | On ART (N=511) | Chi-squared statistic (df) {p-value} | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Sex in past 12 months | 417 | 88.4 | 115 | 77.7 | 10.5 (1){0.001} | 813 | 80.3 | 351 | 72.2 | 12.2(1) {<0.001} |

|

| ||||||||||

| Most recent sex partner typea | 5.8 (2){0.054} | 0.8 (2) {0.673} | ||||||||

| Husband/Wife/Live-in Partner | 169 | 41.3 | 61 | 53.0 | 306 | 38.1 | 141 | 40.2 | ||

| Girlfriend/Boyfriend not live-in | 233 | 57.0 | 51 | 44.4 | 479 | 59.6 | 200 | 57.0 | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Consistency of Condom Usea | 31.7 (3) {0.001} | 51.5 (3) {<0.001} | ||||||||

| Every time | 143 | 34.9 | 66 | 57.4 | 271 | 33.5 | 188 | 53.7 | ||

| Almost every time | 22 | 5.4 | 12 | 10.4 | 41 | 5.1 | 18 | 5.1 | ||

| Sometimes | 59 | 14.4 | 16 | 13.9 | 162 | 20.0 | 67 | 19.1 | ||

| Never | 186 | 45.4 | 21 | 18.3 | 336 | 41.5 | 77 | 22.0 | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Condom at last sexa | 182 | 45.3 | 82 | 73.2 | 27.4 (1) {<0.001} | 359 | 44.5 | 224 | 65.5 | 42.2 (1) {<0.001} |

|

| ||||||||||

| Multiple Partnersa | 87 | 20.9 | 17 | 14.9 | 2.04 (1) {0.153} | 62 | 7.7 | 18 | 5.1 | 2.5 (1) {0.114} |

|

| ||||||||||

| Binge Drinking | 7.6 (2) {0.023} | 14.3 (2) {0.001} | ||||||||

| No drinking in past 12 months | 233 | 46.7 | 90 | 58.8 | 834 | 79.4 | 435 | 87.0 | ||

| Drinking with no binge drinking | 96 | 19.2 | 19 | 12.4 | 100 | 9.5 | 25 | 5.0 | ||

| Binge drinking | 170 | 34.1 | 44 | 28.8 | 117 | 11.1 | 40 | 8.0 | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Disclosed Status to all current partners | 39.1 (2) {<0.001} | 44.9 (2) {<0.001} | ||||||||

| No | 221 | 44.8 | 28 | 18.2 | 301 | 29.1 | 71 | 14.3 | ||

| Yes | 228 | 46.3 | 96 | 62.3 | 557 | 53.9 | 299 | 60.3 | ||

| No partner | 44 | 8.9 | 30 | 19.5 | 175 | 16.9 | 126 | 25.4 | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Received HIV test and results in past year | 197 | 39.6 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 539 | 52.1 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

|

| ||||||||||

| Exposure to Healthcare services in past 6 months | 206 | 41.0 | 110 | 71.0 | 42.8 (1) {<0.001} | 526 | 50.2 | 358 | 71.5 | 62.6 (1) {<0.001} |

Denominator represents only individuals who report being sexually active in the past 12 months

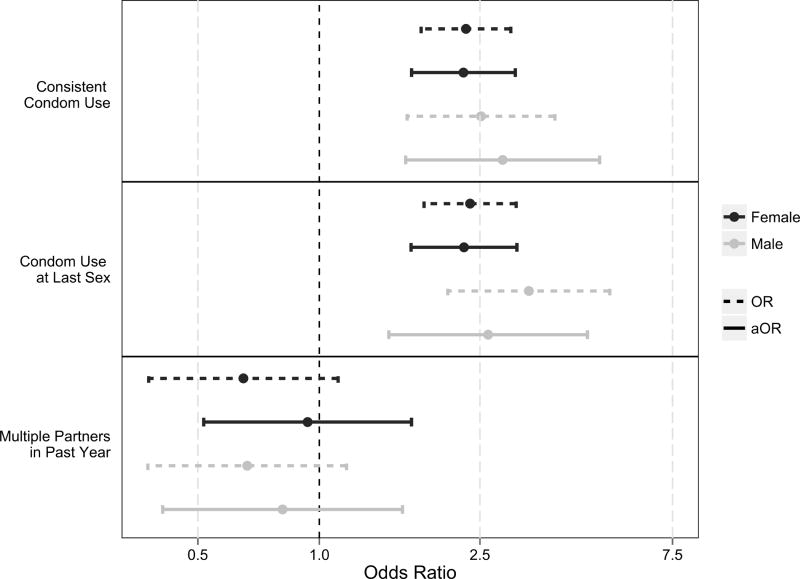

Figure 1 shows the unadjusted and adjusted associations between ART and sexual risk behaviors. For males and females, the odds of reporting condom use were statistically significantly higher for individuals on ART compared to those not on ART, even after adjusting for potential confounders (Males: consistent condom use aOR=2.8, 95% CI=1.6– 4.9, condom use at last sex aOR=2.6, 95% CI=1.5–4.6; Females: consistent condom use aOR=2.3, 95% CI=1.7–3.1, condom use at last sex aOR=2.3, 95% CI=1.7–3.1). There was no statistically significant difference in reporting of multiple sexual partners in the past year comparing those on ART to those not on ART after adjusting for other potential confounders for either males or females (among males: aOR=0.81, 95% CI=0.41–1.6; among females: aOR=0.94, 95% CI=0.52–1.7). We assessed for mediation and effect modification by exposure to healthcare services in the past year and did not find a large impact (<10%) as a mediator nor statistically significant interaction term. We additionally stratified our analyses by respondents’ having disclosed their HIV status to partners, and respondents’ awareness of their partners’ status, but found our conclusions did not change.

Figure 1. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for sexual behaviors by ART status among South African males and females living with HIV, 2012.

All aORs are adjusted for age category, race, income in past month, locality type, partner type, education, and alcohol use, while condom use outcomes additionally adjust for disclosure of HIV status to partner and alternative contraceptive use

DISCUSSION

In this nationally representative population-based survey of South African adults, we found evidence of increased sexual risk behavior among people living with HIV not on ART compared to those who are on ART. Individuals on ART were more likely to report condom use and disclosing their status to partners, and less likely to report hazardous alcohol use.

The above results indicate the necessity for HIV prevention interventions to target individuals who are not yet on ART with behavioral HIV prevention interventions. Individuals not on ART reported high levels of sexual risk. Nearly two-thirds of HIV-positive individuals not on ART reported inconsistent condom use and over half of the same individuals did not use a condom at last sex. This suggests that the individuals with the greatest potential for onward transmission of HIV, those who are not on ART who likely have higher viral loads, are engaging in behaviors that put their sexual partners at high risk of infection. However, identifying this population for behavioral prevention interventions is a major challenge, given the possibility that these individuals are simply less likely or willing to engage with public health or clinical medicine and the combined challenges of sexual behavior change while simultaneously linking a newly diagnosed positive individual to clinical care.

Individuals on ART also reported much higher levels of recent interaction with healthcare providers. It is possible that the lower reported levels of sexual risk behavior can be explained by this interaction, though effect modification and mediation by having seen a healthcare provider in the past 6 months was not significant. South African ART counseling guidelines include risk reduction/prevention for positives[4]. It is unclear if the effect we observe is simply a case of individuals who interact with the healthcare system knowing the “right” answers and therefore our results potentially could be due to social desirability bias, or if the observed effect is a truly protective effect.

There are numerous potential limitations to the results presented. The cross-sectional nature of the data collected in SABSSM IV means that no assessments of temporality may be made for the associations examined. We did not ask participants if they were aware of their HIV status, and therefore HIV-1 antibody-positive participants not on antiretroviral therapy will represent a mixture of participants who are aware of their status but not yet on ART (potentially because their CD4+ cell count is above 350 cells/mm3), aware of their status and non-adherent to their ART regimen, and individuals who are unaware of their status. We are unable to assess if differences in reported sexual behavior could be attributed to simply awareness of HIV status, or to being on ART, which is potentially a major confounder of our results. Previous studies have found that self-reported HIV status and self-reported ART use are often misreported when compared to biological HIV testing and ART detection[33,34], making assessing awareness of HIV status and HIV care in household-based cross-sectional studies very challenging. Individuals living with HIV but unaware of their status have been shown to engage in the highest risk behavior[35–37], and may thus increase the risk profile of the not on ART group in our study.

We are thus additionally unable to separate out the sexual behavior of participants who are non-adherent to ART. However, the individuals who are on ART but non-adherent to their medications may be of the greatest interest in assessing potential for “risk compensation,” in which individuals engage in higher risk behaviors because they perceive themselves to be protected[38]. Future studies should differentiate between non-adherence and individuals not yet on ART. Further, we did not measure CD4 levels to determine whether those not on ART would meet local treatment guidelines. Nor did we measure whether individuals were aware of the protective nature of ART on HIV transmission. As the results of HPTN 052 become increasingly widespread, it will be vital to understand if risk compensation attenuates the effect of treatment as prevention[39].

Additionally, sexual behavior was ascertained through participant self-report. Given the wide-scale general population knowledge about HIV and the numerous health education campaigns that have been conducted in South Africa, there is substantial reason to expect that self-report may be more conservative than true sexual behavior (though there is some question as to whether females under-report sexual activity while males over-report sexual activity[40]). Of greatest concern is the potential that participants who are on ART and therefore receiving counseling on safe sex are more likely to under-report their sexual activity than those who are not in regular care. There is little guidance to correct for this potential differential misclassification.

Cross-sectional studies have several additional limitations in answering the question of differences in sexual behavior between those on and not on ART. Particularly, the individuals who initiate and maintain ART likely are inherently different from the individuals who do not initiate ART or those who never get tested, and this unmeasured confounding may lead to uninterpretable results. As a result, future studies assessing differential sexual risk taking by ART status should have more rigorous longitudinal designs and assess the nuances in the population not on ART.

As “treatment as prevention” strategies are increasingly implemented, it will remain vital to understand the sexual behavior of individuals living with HIV whether on or not on ART. Implementing HIV prevention interventions to decrease sexual risk behaviors of individuals not on ART are of the greatest importance for curtailing the HIV epidemic, though to identify these individuals they will need to be tested, setting them onto the “continuum of care.” Additionally, as the public becomes increasingly aware of the protective nature of ART against transmission, assessing the potential for increased risk behaviors among those on ART will also be of interest. Continued monitoring of the sexual behaviors of individuals living with HIV and implementation of behavioral strategies to modify risky sexual behaviors among these individuals remain key strategic targets for the HIV response.

Acknowledgments

This article has been supported by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) under the terms of 3U2GGH000570. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of CDC. We also acknowledge the John Hopkins University Center for AIDS Research (1P30AI094189) and the National Institutes of Health (T32AI102623).

References

- 1.Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi L, et al. South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behaviour Survey, 2012. Cape Town: HSRC Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdool Karim SS, Abdool Karim Q, Gouws E, Baxter C. Global epidemiology of HIV-AIDS. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2007 Mar;21(1):1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.South African National AIDS Council. [Accessed 2 Aug 2014];Republic of South Africa Global AIDS Response Progress Report. 2013 Available at: http://sanac.org.za/publications/reports/doc_download/61-ungass-south-africa-report.

- 4.Department of Health Republic of South Africa. [Accessed 2 Aug 2014];South African Antiretroviral Treatment Guidelines. 2013 Available at: http://www.sahivsoc.org/upload/documents/2013ARTTreatmentGuidelinesFinal25March2013corrected.pdf.

- 5.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug 11;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wamoyi J, Mbonye M, Seeley J, Birungi J, Jaffar S. Changes in sexual desires and behaviours of people living with HIV after initiation of ART: implications for HIV prevention and health promotion. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:633. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Redd AD, Quinn TC, Tobian AA. Frequency and implications of HIV superinfection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013 Jul;13(7):622–8. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70066-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization HIV/AIDS Programme. [Accessed 1 Aug 2013];Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach. 2013 Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85321/1/9789241505727_eng.pdf. [PubMed]

- 9.Peltzer K, Friend-du Preez N, Ramlagan S, Anderson J. Antiretroviral treatment adherence among HIV patients in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:111. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maqutu D, Zewotir T, North D, Naidoo K, Grobler A. Determinants of optimal adherence over time to antiretroviral therapy amongst HIV positive adults in South Africa: a longitudinal study. AIDS Behav. 2011 Oct;15(7):1465–74. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9688-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stolte IG, Dukers NH, Geskus RB, Coutinho RA, de Wit JB. Homosexual men change to risky sex when perceiving less threat of HIV/AIDS since availability of highly active antiretroviral therapy: a longitudinal study. AIDS. 2004 Jan 23;18(2):303–9. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200401230-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dukers NH, Goudsmit J, de Wit JB, Prins M, Weverling GJ, Coutinho RA. Sexual risk behaviour relates to the virological and immunological improvements during highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 2001 Feb 16;15(3):369–78. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200102160-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ostrow DE, Fox KJ, Chmiel JS, et al. Attitudes towards highly active antiretroviral therapy are associated with sexual risk taking among HIV-infected and uninfected homosexual men. AIDS. 2002 Mar 29;16(5):775–80. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200203290-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tun W, Gange SJ, Vlahov D, Strathdee SA, Celentano DD. Increase in sexual risk behavior associated with immunologic response to highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected injection drug users. Clin Infect Dis. 2004 Apr 15;38(8):1167–74. doi: 10.1086/383033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eisele TP, Mathews C, Chopra M, et al. High levels of risk behavior among people living with HIV Initiating and waiting to start antiretroviral therapy in Cape Town South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2008 Jul;12(4):570–7. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9279-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peltzer K, Ramlagan S. Safer sexual behaviours after 1 year of antiretroviral treatment in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: a prospective cohort study. Sex Health. 2010 Jun;7(2):135–41. doi: 10.1071/SH09109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Venkatesh KK, de Bruyn G, Lurie MN, et al. Decreased sexual risk behavior in the era of HAART among HIV-infected urban and rural South Africans attending primary care clinics. AIDS. 2010 Nov 13;24(17):2687–96. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833e78d4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eisele TP, Mathews C, Chopra M, et al. Changes in risk behavior among HIV-positive patients during their first year of antiretroviral therapy in Cape Town South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2009 Dec;13(6):1097–105. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9473-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Apondi R, Bunnell R, Ekwaru JP, et al. Sexual behavior and HIV transmission risk of Ugandan adults taking antiretroviral therapy: 3 year follow-up. AIDS. 2011 Jun 19;25(10):1317–27. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328347f775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dia A, Marcellin F, Bonono RC, et al. Prevalence of unsafe sex with one’s steady partner either HIV-negative or of unknown HIV status and associated determinants in Cameroon (EVAL ANRS12–116 survey) Sex Transm Infect. 2010 Apr;86(2):148–54. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.035147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bateganya M, Colfax G, Shafer LA, et al. Antiretroviral therapy and sexual behavior: a comparative study between antiretroviral- naive and -experienced patients at an urban HIV/AIDS care and research center in Kampala, Uganda. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2005 Nov;19(11):760–8. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moatti JP, Prudhomme J, Traore DC, et al. Access to antiretroviral treatment and sexual behaviours of HIV-infected patients aware of their serostatus in Cote d’Ivoire. AIDS. 2003 Jul;17(Suppl 3):S69–77. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200317003-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luchters S, Sarna A, Geibel S, et al. Safer sexual behaviors after 12 months of antiretroviral treatment in Mombasa, Kenya: a prospective cohort. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008 Jul;22(7):587–94. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wandera B, Kamya MR, Castelnuovo B, et al. Sexual behaviors over a 3-year period among individuals with advanced HIV/AIDS receiving antiretroviral therapy in an urban HIV clinic in Kampala, Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011 May 1;57(1):62–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318211b3f2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thirumurthy H, Goldstein M, Zivin JG, Habyarimana J, Pop-Eleches C. Behavioral Responses of Patients in AIDS Treatment Programs: Sexual Behavior in Kenya. Forum Health Econ Policy. 2012 Apr 19;15(2) doi: 10.1515/1558-9544.1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yalew E, Zegeye DT, Meseret S. Patterns of condom use and associated factors among adult HIV positive clients in North Western Ethiopia: a comparative cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:308. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bunnell R, Ekwaru JP, Solberg P, et al. Changes in sexual behavior and risk of HIV transmission after antiretroviral therapy and prevention interventions in rural Uganda. AIDS. 2006 Jan 2;20(1):85–92. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000196566.40702.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berhan A, Berhan Y. Is the Sexual Behaviour of HIV Patients on Antiretroviral therapy safe or risky in Sub-Saharan Africa? Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. AIDS Res Ther. 2012;9(1):14. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-9-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olley BO. Higher-risk sexual behaviour among HIV patients receiving antiretroviral treatment in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr J AIDS Res. 2008;7(1):71–8. doi: 10.2989/AJAR.2008.7.1.8.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shafer LA, Nsubuga RN, White R, et al. Antiretroviral therapy and sexual behavior in Uganda: a cohort study. AIDS. 2011 Mar 13;25(5):671–8. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328341fb18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pearson CR, Cassels S, Kurth AE, Montoya P, Micek MA, Gloyd SS. Change in sexual activity 12 months after ART initiation among HIV-positive Mozambicans. AIDS Behav. 2011 May;15(4):778–87. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9852-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Statistics South Africa. [Accessed 2 Aug 2014];Census 2011 South Africa. 2012 Available at: http://www.statssa.gov.za/Publications/P03014/P030142011.pdf.

- 33.Fishel J, Barrere B, Kishor S. DHS Working Papers No. 81. Calverton, Maryland, USA: ICF International; 2012. Validity of data on self-reported HIV status and implications for measurement of ARV coverage in Malawi. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fogel JM, Wang L, Parsons TL, et al. Undisclosed antiretroviral drug use in a multinational clinical trial (HIV Prevention Trials Network 052) J Infect Dis. 2013 Nov 15;208(10):1624–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dokubo EK, Shiraishi RW, Young PW, et al. Awareness of HIV status, prevention knowledge and condom use among people living with HIV in Mozambique. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e106760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenberg NE, Pettifor AE, De Bruyn G, et al. HIV testing and counseling leads to immediate consistent condom use among South African stable HIV-discordant couples. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013 Feb 1;62(2):226–33. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31827971ca. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bunnell R, Opio A, Musinguzi J, et al. HIV transmission risk behavior among HIV-infected adults in Uganda: results of a nationally representative survey. AIDS. 2008 Mar 12;22(5):617–24. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f56b53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cassell MM, Halperin DT, Shelton JD, Stanton D. Risk compensation: the Achilles’ heel of innovations in HIV prevention? BMJ. 2006 Mar 11;332(7541):605–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7541.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Venkatesh KK, Flanigan TP, Mayer KH. Is expanded HIV treatment preventing new infections? Impact of antiretroviral therapy on sexual risk behaviors in the developing world. AIDS. 2011 Oct 23;25(16):1939–49. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834b4ced. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clark S, Kabiru C, Zulu E. Do men and women report their sexual partnerships differently? Evidence from Kisumu, Kenya. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2011 Dec;37(4):181–90. doi: 10.1363/3718111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]