Abstract

Due to an increasing incidence and more frequent recognition by endoscopists, gastrointestinal follicular lymphoma has been established as a variant of follicular lymphoma. However, due to its rarity, there are no established guidelines on the optimal diagnostic strategy for patients with primary gastrointestinal follicular lymphoma or secondary gastrointestinal involvement of systemic follicular lymphoma. This review offers an overview and pitfalls to avoid during the initial diagnostic workup of this disease entity. Previously reported case reports, case series, and retrospective studies are reviewed and focus on the disease’s endoscopic and histological features, the roles of computed tomography and positron emission tomography scanning, the clinical utility of the soluble interleukin-2 receptor, and the possible pathogenesis.

Keywords: Follicular lymphoma, Gastrointestinal lymphoma, Duodenal neoplasms, Intestinal neoplasms, Gastrointestinal endoscopy

Core tip: This review provides an overview regarding the initial diagnostic workup of gastrointestinal follicular lymphoma. Previously reported case reports, case series, and retrospective studies are reviewed, and focus on the disease’s endoscopic and histological features, the roles of computed tomography and positron emission tomography scanning, the clinical utility of the soluble interleukin-2 receptor, and the possible pathogenesis. Although there is no doubt that endoscopic examinations play a major role in the diagnosis of this disease, gastroenterologists should also keep in mind that follicular lymphoma patients with gastrointestinal involvement must be investigated according to the general guidelines for systemic follicular lymphoma.

INTRODUCTION

Follicular lymphoma is the most common subtype of indolent non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. This neoplasm originates in germinal center B cells and is pathologically characterized by centrocytes and centroblasts, typically forming follicular patterns of various sizes[1,2]. At the time of diagnosis, most patients with follicular lymphoma are in advanced stage III or IV of the Ann Arbor staging system. Only 5%-10% of patients present with early stage I or II disease[3,4]. Meanwhile, this disease primarily or secondarily involves non-hematopoietic extra-nodal sites, such as the gastrointestinal tract, skin, ocular adnexa, breast, and testis[1]. The gastrointestinal tract is the most common site of involvement.

Historically, the disease entity of gastrointestinal follicular lymphoma was established within the 2000’s. Misdraji et al[5] reported the first case of primary follicular lymphoma of the duodenum in 1997. Yoshino et al[6] subsequently summarized their cases and reported in 2000 that duodenal follicular lymphoma is frequently found in the second part of the duodenum. As the concept of this disease has gained in popularity, multiple case reports and case series have been reported. As a result, primary intestinal follicular lymphoma was formally cited as a variant of follicular lymphoma in the latest version of the classification of lymphoid tissues issued by the World Health Organization[1].

Gastroenterologists are now playing an important role in the detection, diagnosis, and initial management of this disease. However, because of its rarity, there have been no guidelines published regarding the diagnosis and initial management of patients with primary intestinal follicular lymphoma or those with secondary gastrointestinal involvement of systemic follicular lymphoma. Here we review relevant clinical studies and case reports for a better understanding of the pearls and pitfalls of the diagnosis and initial workup of this disease entity.

OVERVIEW

Initial diagnostic workup for patients with primary or secondary gastrointestinal involvement of follicular lymphoma should be performed according to the guidelines for follicular lymphoma of nodal origin. For example, guidelines for follicular lymphoma have been issued by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network[7], the European Society for Medical Oncology[8], the East Midlands Cancer Network[9], and British[10], Italian[11], and Chinese working groups[12]. In addition, recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma were published in 2014, which were discussed and agreed upon in workshops held at the International Conference on Malignant Lymphoma in Lugano, Switzerland[13].

In these guidelines, the initial diagnostic workup is composed of the following principles: (1) diagnosis should start with tissue sampling (e.g., lymph node biopsy) followed by adequate histological assessment; (2) the stage of the disease should be assessed by computed tomography (CT) scanning of the whole body and a bone marrow examination; and (3) risk assessment using the Follicular Lymphoma-specific International Prognostic Index (FLIPI)[14] and/or FLIPI2 should be performed[15]. Taking these principles into account along with the previously reported peculiar features of intestinal follicular lymphoma, we herein propose initial diagnostic workup strategies for patients with primary or secondary gastrointestinal involvement of follicular lymphoma (Table 1). Commentaries on each of the items listed are described below.

Table 1.

Initial diagnostic workup for patients with primary or secondary gastrointestinal involvement of follicular lymphoma

| Required evaluations |

| Performance status |

| Physical exams of the peripheral lymph nodes, liver, spleen, and Waldeyer’s ring. |

| Blood tests including a complete blood count and leukocyte differential, LDH, β2-microglobulin, uric acid, creatinine, electrolytes including calcium and phosphate, liver function tests, albumin, and serology tests for hepatitis B, C, and HIV. |

| Immunoglobulins and electrophoresis of proteins |

| Esophagogastroduodenoscopy, colonoscopy, and enteroscopy1 |

| PET-CT scanning of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis |

| Chest X-ray, abdominal ultrasound |

| Bone marrow biopsy |

| When planning chemotherapy: electrocardiogram, cardiac ultrasound2, creatinine clearance |

| Optional |

| sIL-2R |

| Helicobacter pylori test |

| Magnetic resonance imaging of the CNS3 |

| Flow cytometry, FISH/PCR for BCL-2 rearrangement of the bone marrow cells |

| Reproductive counseling to preserve fertility before chemotherapy |

Required when planning radiotherapy. Video capsule enteroscopy and/or balloon assisted enteroscopy.

Required before chemotherapy with anthracycline-based regimens or autologous stem cell transplantation.

Required only for patients with suspected CNS involvement. HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus; CNS: Central nervous system; sIL-2R: Soluble interleukin-2 receptor; CT: Computed tomography; PET: Positron emission tomography; FISH: Fluorescence in situ hybridization; PCR: Polymerase chain reaction; LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase; BCL-2: B-cell lymphoma 2.

CLINICAL AND LABORATORY ASSESSMENT

As a general rule, comprehensive assessment of clinical features and laboratory test results are important for all patients with newly diagnosed follicular lymphoma[8]. Patients with primary intestinal follicular lymphoma generally lack systemic symptoms, whereas systemic follicular lymphoma patients with secondary gastrointestinal involvement may exhibit symptoms. Since most gastrointestinal lesions are neither mass-forming nor ulcerative, more than half of patients present without gastrointestinal follicular lymphoma-related manifestations.

Yamamoto et al[16] reviewed 150 previously reported cases and noted that 65 patients (43.3%) were asymptomatic while 14 (9.3%) presented with ambiguous gastrointestinal symptoms including abdominal discomfort and heartburn. Other symptoms include abdominal pain (n = 43, 28.7%), intestinal obstruction-related symptoms such as nausea and vomiting (n = 12, 8.0%), and intestinal bleeding such as tarry and bloody stool (n = 9, 6.0%). A multi-institutional survey in Japan summarizing 125 patients with primary gastrointestinal follicular lymphoma reported that 96 patients (76.8%) were asymptomatic. The remaining patients presented with abdominal pain (n = 10, 8.0%), abdominal discomfort (n = 13, 10.4%), intestinal obstruction (n = 5, 4.0%), or diarrhea (n = 1, 0.8%)[17].

Information about allergies, previous illnesses and surgeries, performance status, and results of physical exams of the peripheral lymph nodes, liver, spleen, and Waldeyer’s ring should also be recorded at the initial presentation[8]. Blood tests should include hemoglobin, β2-microglobulin, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels, since this information is indispensable for risk stratification according to FILIPI and FLIPI2, as described below[14,15].

ENDOSCOPIC FEATURES

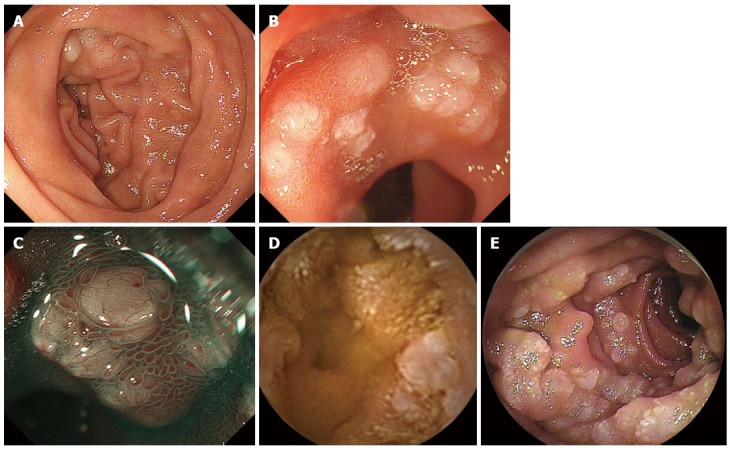

When it involves the gastrointestinal tract, primary gastrointestinal follicular lymphoma most frequently affects the small intestine[1,17]. In most patients, this disease is diagnosed by esophagogastroduodenoscopy as whitish lesions in the duodenum (Figure 1)[16-18]. The typical endoscopic image has been described in various terms such as small polypoid nodules, multiple polypoid lesions, multiple small polyps, multiple nodules, or multiple granules[16]. Other macroscopic features are infrequent, but it can present as erosions or ulcers[19].

Figure 1.

Endoscopic features of intestinal follicular lymphoma in a 63-year-old woman. A: This case was diagnosed as follicular lymphoma with duodenal and jejunal lesions, and mesenteric lymph node involvement. The duodenal lesions are observed as multiple whitish nodules; B: Magnifying observation reveals opaque white depositions; C: Narrow-band imaging visualizes dilated microvessels on the surface of the white depositions; D: Video capsule enteroscopy shows multiple whitish granules in the jejunum; E: Double-balloon enteroscopy images of a jejunal lesion.

Any jejunal and ileal involvement shows a morphology similar to the duodenal lesions (Figure 1D and E)[16,20-22]. Since these lesions generally remain small, most of these cases are asymptomatic or only exhibit symptoms not related to the lymphoma lesions. In rare instances, small intestinal lesions form ulcers, luminal stenosis, and bulky tumors accompanied by ulcers and/or wall thickening, probably resulting from an increased number of infiltrated lymphoma cells within the small intestinal wall[23,24]. Among follicular lymphoma cases presenting with intestinal involvement, 66.7% to 100% of the patients presented with multiple follicular lymphoma lesions in the jejunum and/or ileum[4,20-22,24-26]. As described below, the sensitivity of CT and positron emission tomography (PET) scanning is not sufficient to diagnose the intestinal lesions of follicular lymphoma. Therefore, primary intestinal follicular lymphoma patients under consideration for radiotherapy should be investigated by CT or PET scanning and also by enteroscopy examinations such as video capsule enteroscopy or balloon-assisted enteroscopy.

Gastric involvement of follicular lymphoma has been occasionally reported. It can vary from protruding lesions[27] to superficial, shallow depressed lesions[28]. Only eight case reports of follicular lymphomas with colorectal involvement that describe detailed features have been reported[29-36]. Among the reported cases, the endoscopic images in one patient showed a submucosal tumor with ulceration[31]. The other seven patients presented with elevated lesions in the colorectal region without erosions or ulcers. Recently, we summarized 12 additional cases of colorectal follicular lymphoma lesions[37]. Virtually all of the 12 colorectal follicular lymphoma presented as elevated lesions and had no erosions or ulcers. They could be macroscopically subcategorized into papular, polypoid, or flat elevated lesions. Consequently, erosions and ulcer formation are considered to be infrequent events in the colorectal involvement of follicular lymphoma.

MAGNIFYING ENDOSCOPY OBSERVATION

As described above, multiple whitish polypoid lesions are representative macroscopic features of intestinal follicular lymphoma. Recent advances in magnifying endoscopy technology enable visualization of the finer structures of these lesions. Several authors have reported that opaque whitish spots, enlarged villi, and a dilated vascular pattern within the villi are representative magnifying endoscopic features of this disease[38-45]. The whitish color of the intestinal lesions are presumably imparted by the infiltrating lymphoma cells[42,43,46]. Moreover, we speculate that the microstructures observed by magnifying endoscopy reflect the underlying pathological structures.

Pathologically, follicular lymphoma in the small intestine is characterized by infiltration of lymphoma cells within the villi and the development of neoplastic lymphoid follicles. Lymphoid follicles formed in the mucosa or submucosa visually appear as opaque white spots. Infiltration of lymphoma cells results in the swelling of the affected villi producing enlarged whitish villi. Infiltrating follicular lymphoma cells may disturb the perfusion of microvessels in the villi, leading to the dilation of these vessels[44].

These microstructure features are useful to distinguish follicular lymphoma from other whitish lesions in the duodenum. We comparatively analyzed the magnifying endoscopic features of cases with follicular lymphoma (n = 9), lymphangiectasia (n = 7), adenoma (n = 10), duodenitis (n = 4), erosion (n = 1), lymphangioma (n = 1), and hyperplastic polyps (n = 1)[45]. In our study, enlarged villi (8/9, 88.9%), dilated microvessels (5/9, 55.6%), and opaque white spots of various sizes (9/9, 100%) were detected in follicular lymphoma cases. Such magnifying endoscopic features are helpful in terms of the differential diagnosis of follicular lymphoma from lymphangiectasia, adenoma, and duodenitis. Observation of the lymphangiectasia revealed enlarged villi, dilated microvessels, and white spots, but the sizes of the white spots were homogeneous and their margins were clear. Adenoma and duodenitis showed only whitish villi.

Although the lymphangiomas showed a similar microstructure to the follicular lymphoma lesions, they were easily distinguishable based on the macroscopic morphology, since the lymphangioma appeared as a soft submucosal tumor with white spots. Consequently, we consider that magnifying endoscopic observation, in combination with macroscopic morphology, is valuable for prompt endoscopic diagnosis of intestinal follicular lymphoma. We also believe that magnified endoscopy can be applied to detect subtle intestinal involvement of follicular lymphoma[45] and to judge whether complete remission of the intestinal lesions is obtained[46].

HISTOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT OF BIOPSIED SPECIMEN

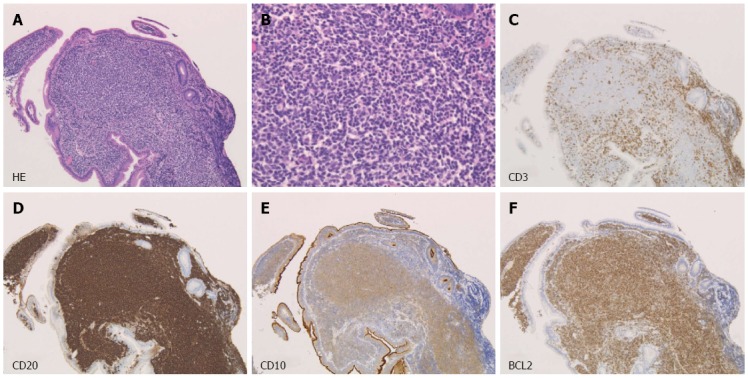

Appropriate pathological assessment is indispensable to the diagnosis of follicular lymphoma (Figure 2). Histologically, this neoplasm is composed of germinal center B cells, typically both centrocytes and centroblasts[1,2]. Pathological grading is done according to the number of centroblasts per 40 × high-power microscopic field (hpf)[1]. It has been reported that more than 95% of gastrointestinal follicular lymphomas are Grade 1 or 2[2].

Figure 2.

Pathological images (the same case shown in Figure 1). A: Neoplastic follicles are seen in the duodenal villi (hematoxylin and eosin staining, × 10); B: The lymphoma cells are composed of small- to medium-sized lymphoid cells (hematoxylin and eosin staining, × 40); C: The lymphoma cells are negative for CD3 (× 10); D: The lymphoma cells are positive for CD20 (× 10); E: The lymphoma cells are positive for CD10 (× 10); F: The lymphoma cells are positive for BCL2 (× 10).

Typical microscopic features of duodenal follicular lymphoma include: (1) small to medium-sized lymphoid cells forming tumor follicles, and (2) infiltration of tumor cells involving the duodenal villi[2]. On pathological assessment of gastrointestinal follicular lymphoma lesions, the main differential diagnoses are extra-nodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma), mantle cell lymphoma, and reactive lymphoid hyperplasia. The neoplastic cells in follicular lymphoma, MALT lymphoma, and mantle cell lymphoma exhibit morphological similarities, since these lymphomas predominantly consist of small- to medium-sized cells of B-lymphocyte origin. Consequently, in general, subcategorizing these B-cell lymphomas according to the morphological features of the lymphoma cells is often difficult and requires immunohistochemical staining. An immunophenotyping result of B-cell lymphoma (BCL)2+, BCL6+, cluster of differentiation (CD)10+, CD5-, CD43-, and cyclin D1-, in addition to being positive for B-cell associated antigens such as CD19, CD20, CD22, and CD79a, is a distinctive feature of follicular lymphoma[1]. Translocation t(14;18)(q32;q21) is also a characteristic feature of this disease, and detection of such cytogenetic abnormalities is also useful for diagnosis.

We investigated the diagnostic accuracy of the initial pathological evaluation for gastrointestinal follicular lymphomas[27]. Forty-eight patients were included, and nine (18.8%) patients were found to have been incorrectly diagnosed at the initial biopsy examination as having MALT lymphoma (n = 4), necrotic tissue (n = 2), duodenitis (n = 1), or suspected lymphoma of unspecified subtype (n = 2). Misdiagnosis of gastrointestinal follicular lymphoma as MALT lymphoma has been reported by other authors as well[47,48]. We found two major problems that might lead to misinterpretation of the pathological diagnosis: an incomplete histopathologic evaluation lacking immunophenotyping analysis, and unsuitable biopsy samples taken from erosions or ulcerative lesions that contained scanty lymphoma cells or no lymphoid follicles[27]. For patients in whom gastrointestinal low-grade B-cell lymphoma is suspected, physicians should confirm that appropriate immunostaining and/or cytogenetic analysis was performed. In addition, in rare instances presenting with a macroscopic form of erosions or ulcers, extensive pathological analysis by repeat biopsies or surgical resection may be required to reach the correct diagnosis[27].

Histological transformation to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is a critical event associated with poor prognosis. In nodal follicular lymphoma, 28% of patients develop histological transformation within 10 years[49]. However, histological transformation is considered a rare event in primary gastrointestinal follicular lymphoma cases. To the best of our knowledge, only one such case has ever been reported. Miyata-Takata et al[50] described a patient with primary intestinal follicular lymphoma in whom perforation of the ileum occurred and histological transformation was confirmed in the surgical specimen.

PET SCANNING

The consensus reached in an expert meeting on imaging evaluation of lymphomas held in 2013 stated that PET-CT is more accurate, with an increased sensitivity for staging, than contrast-enhanced CT scanning[51]. Upstaging with detection of extra-nodal disease by PET scanning occurs in some patients, which results in management alterations[52]. PET scanning is particularly recommended for stage I and II patients under consideration for radiotherapy as a curative treatment, since they require precise determination of the disease extent[9,53]. The percentage of follicular lymphoma cases with tracer-avid lesions has been reported to range from 91% to 100%[52,54-58].

Meanwhile, our previous study showed that 19 out of 41 patients had true tracer uptake in the involved gastrointestinal lesions, resulting in a sensitivity of 46.3%[59]. However, 22 patients (53.7%) showed false-negative tracer uptake, and two (4.9%) exhibited both true-positive and false-negative tracer uptake in gastrointestinal lesions. Consequently, the gastrointestinal lesions were undetectable in 24 patients (58.5%). Moreover, false-positive tracer uptake is another disadvantage associated with PET scanning of the gastrointestinal system. Physiological intestinal spasms, inflammatory conditions such as infections and hemorrhoids, and even constipation are possible causes of false-positives[60,61].

These results indicate that, although the sensitivity of PET scanning is likely higher than that of CT, both imaging studies are not completely reliable for the diagnosis of follicular lymphoma lesions in the gastrointestinal tract. We believe that patients with primary intestinal follicular lymphoma who are eligible for curative radiotherapy should undergo endoscopic examinations, that is, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, colonoscopy, plus balloon-assisted enteroscopy or video capsule enteroscopy, to evaluate the entire gastrointestinal tract[26,59].

STAGING

Based on a careful evaluation of the disease extent by endoscopy, CT and/or PET scanning, and bone marrow examinations, lymphoma patients are generally assigned an anatomic stage using the Ann Arbor system[62]. For lymphomas with gastrointestinal involvement, the Lugano system is also applicable for staging[63,64]. The Lugano system staging seems to be suitable for primary gastrointestinal follicular lymphoma patients, because involvement of multiple intestinal sites is common. However, the Ann Arbor classification is still required for risk stratification by FLIPI. Evaluating patients with both staging systems is recommended during the initial diagnostic workup and when lymphoma progression occurs.

SOLUBLE INTERLEUKIN-2 RECEPTOR

Serum soluble interleukin-2 receptor (sIL-2R) levels are widely measured and used as a marker for various lymphoproliferative disorders. Mir et al[65] reported that, based on the pretreatment serum samples from nodal follicular lymphoma patients (n = 209) and from matched controls (n = 400), elevated serum levels of IL-2R were associated with poor outcomes.

We investigated the relationship between sIL-2R levels and other clinical characteristics in follicular lymphoma patients with gastrointestinal involvement[66]. Our study showed that elevated sIL-2R levels correlated with systemic involvement (Ann Arbor system staging IIIES/IV or Lugano system staging II2/IV), involvement of five or more nodal areas, and presentation of bulky tumors in the gastrointestinal tract detectable by CT scanning. Though the differences were not statistically significant, patients with elevated sIL-2R tended to have lower hemoglobin levels. These patients also had a high FLIPI score. Based on our study results, we speculate that elevated sIL-2R levels at initial diagnosis may be associated with a poor prognosis for gastrointestinal follicular lymphoma patients as well as for nodal cases. Another important implication for the management of follicular lymphoma patients with gastrointestinal involvement is that sIL-2R may be a good indicator for monitoring disease relapse or progression, since high sIL-2R levels reflected a large tumor bulk in our patients.

We experienced a case with primary intestinal follicular lymphoma that presented without lymph node involvement, but progression with intra-abdominal lymph node enlargement was documented 11 mo after the initial diagnosis[67]. The patient’s sIL-2R levels were elevated when the progression occurred, suggesting the possible utility of sIL-2R levels as a tumor marker for intestinal follicular lymphomas. Consequently, we believe that sIL-2R levels should be evaluated at the initial workup. Elevation of sIL-2R levels during the follow-up period may be suggestive of relapse or tumor progression in patients with gastrointestinal follicular lymphoma[66,67].

PATHOGENESIS

We previously investigated duodenal follicular lymphoma lesions and reported a deviation of immunoglobulin heavy chain and memory B cell characteristics[68]. Our study results indicate the presence of antigen stimulation, which likely affects the spread of intestinal follicular lymphoma lesions. However, a distinct pathogen has not been identified thus far.

Several case reports showed that eradication treatment of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) resulted in regression of duodenal follicular lymphoma in H. pylori-positive cases[69,70]. However, partial regression of intestinal follicular lymphoma lesions after eradication treatment for H. pylori has been reported even in a case in whom tests for H. pylori infection were negative[71]. The favorable results in the H. pylori-negative case raises the possibility that a microorganism other than H. pylori is an etiologic factor for the development/regression of intestinal follicular lymphoma. Another hypothesis is that spontaneous regression of follicular lymphoma lesions unrelated to the infectious status of H. pylori may have occurred. The natural course of nodal follicular lymphoma is characterized by spontaneous regression in up to 25% of cases[3]. A retrospective study of 63 patients with primary intestinal follicular lymphoma revealed that one of the six patients who received eradication therapy for H. pylori experienced complete regression, whereas no responses were noted in the remaining five patients[4]. Meanwhile, five patients experienced spontaneous complete regression without receiving eradication treatment for H. pylori. At the present time, the pathogenesis of intestinal follicular lymphoma lesions and the mechanism of effect of eradication therapy for H. pylori is unclear[72].

RISK ASSESSMENT ACCORDING TO THE FLIPI AND FLIPI2 SCORES

For risk stratification of follicular lymphoma patients, FLIPI and FLIPI2 have been developed as prognostic indexes. FLIPI is composed of five adverse prognostic factors: (1) patient’s age over 60 years; (2) Ann Arbor stage III or IV; (3) hemoglobin level below 12 g/dL; (4) five or more involved nodal areas; and (5) LDH level above the normal limit[14]. Three risk groups were defined: low risk (zero or one adverse factor), intermediate risk (two factors), and poor risk (three to five factors).

FLIPI2 consists of a different combination of five adverse prognostic factors: (1) patient’s age over 60 years; (2) bone marrow involvement; (3) hemoglobin level below 12 g/dL; (4) longest diameter of the largest involved node greater than 6 cm; and (5) β2-microglobulin level above the normal limit[15]. Three risk groups were defined: low risk (zero adverse factors), intermediate risk (one to two factors), and poor risk (three to five factors).

Despite the usefulness of these risk assessment systems in nodal cases[73-76], no studies have been conducted on intestinal follicular lymphoma patients. One of the issues regarding FLIPI and FLIPI2 systems is that the proportion of patients in the three groups is unlikely to be balanced, since most of the patients with primary intestinal follicular lymphoma are classified as “low risk” or “intermediate risk”[66]. Further investigation is required to prove the utility of FLIPI and FLIPI2 or to establish other risk assessment methods for intestinal follicular lymphoma patients.

CONCLUSION

In this review, we provided initial diagnostic workup strategies for a more accurate and timely diagnosis of patients with follicular lymphoma in the gastrointestinal tract, particularly highlighting the importance of endoscopic examinations. Though there is no doubt that endoscopic examinations play a major role in the diagnosis of this disease entity, gastroenterologists should also keep in mind that follicular lymphoma patients with gastrointestinal involvement must be investigated according to the general guidelines for systemic follicular lymphoma. We believe the pearls and pitfalls described herein can be helpful for a better understanding of the diagnosis and initial workup of this disease.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All of the authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest associated with this article.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: July 30, 2015

First decision: September 11, 2015

Article in press: October 13, 2015

P- Reviewer: Ruskone-Fourmestraux A, Zhao JB S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

References

- 1.Harris NL, Swerdlow SH, Jaffe ES, Ott G, Nathwani BN, de Jong D, Yoshino T, Spagnolo D. Follicular lymphoma. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe E, Pileri SA, et al., editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon: IARC; 2008. pp. 220–226. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takata K, Miyata-Takata T, Sato Y, Yoshino T. Pathology of follicular lymphoma. J Clin Exp Hematop. 2014;54:3–9. doi: 10.3960/jslrt.54.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dreyling M, Ghielmini M, Marcus R, Salles G, Vitolo U. Newly diagnosed and relapsed follicular lymphoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2011;22 Suppl 6:vi59–vi63. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmatz AI, Streubel B, Kretschmer-Chott E, Püspök A, Jäger U, Mannhalter C, Tiemann M, Ott G, Fischbach W, Herzog P, et al. Primary follicular lymphoma of the duodenum is a distinct mucosal/submucosal variant of follicular lymphoma: a retrospective study of 63 cases. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1445–1451. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.9193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Misdraji J, Fernandez del Castillo C, Ferry JA. Follicle center lymphoma of the ampulla of Vater presenting with jaundice: report of a case. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:484–488. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199704000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshino T, Miyake K, Ichimura K, Mannami T, Ohara N, Hamazaki S, Akagi T. Increased incidence of follicular lymphoma in the duodenum. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:688–693. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200005000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zelenetz AD, Gordon LI, Wierda WG, Abramson JS, Advani RH, Andreadis CB, Bartlett N, Bellam N, Byrd JC, Czuczman MS, et al. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, version 2.2014. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12:916–946. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dreyling M, Ghielmini M, Marcus R, Salles G, Vitolo U, Ladetto M. Newly diagnosed and relapsed follicular lymphoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2014;25 Suppl 3:iii76–iii82. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Available from: http://www.eastmidlandscancernetwork.nhs.uk/Library/FollicularClinicalGuidelinesNewTemplateFeb20111.pdf.

- 10.McNamara C, Davies J, Dyer M, Hoskin P, Illidge T, Lyttelton M, Marcus R, Montoto S, Ramsay A, Wong WL, et al. Guidelines on the investigation and management of follicular lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2012;156:446–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zinzani PL, Marchetti M, Billio A, Barosi G, Carella AM, Lazzarino M, Martelli M, Rambaldi A, Rigacci L, Tarella C, et al. SIE, SIES, GITMO revised guidelines for the management of follicular lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2013;88:185–192. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of follicular lymphoma in China. Cancer Biol Med. 2013;10:36–42. doi: 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, Cavalli F, Schwartz LH, Zucca E, Lister TA. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3059–3068. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solal-Céligny P, Roy P, Colombat P, White J, Armitage JO, Arranz-Saez R, Au WY, Bellei M, Brice P, Caballero D, et al. Follicular lymphoma international prognostic index. Blood. 2004;104:1258–1265. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Federico M, Bellei M, Marcheselli L, Luminari S, Lopez-Guillermo A, Vitolo U, Pro B, Pileri S, Pulsoni A, Soubeyran P, et al. Follicular lymphoma international prognostic index 2: a new prognostic index for follicular lymphoma developed by the international follicular lymphoma prognostic factor project. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4555–4562. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.3991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamamoto S, Nakase H, Yamashita K, Matsuura M, Takada M, Kawanami C, Chiba T. Gastrointestinal follicular lymphoma: review of the literature. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:370–388. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0182-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takata K, Okada H, Ohmiya N, Nakamura S, Kitadai Y, Tari A, Akamatsu T, Kawai H, Tanaka S, Araki H, et al. Primary gastrointestinal follicular lymphoma involving the duodenal second portion is a distinct entity: a multicenter, retrospective analysis in Japan. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1532–1536. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shia J, Teruya-Feldstein J, Pan D, Hegde A, Klimstra DS, Chaganti RS, Qin J, Portlock CS, Filippa DA. Primary follicular lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract: a clinical and pathologic study of 26 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:216–224. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200202000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takeuchi K, Iwamuro M, Imagawa A, Kubota Y, Miyatani K, Takata K, Okada H. Primary follicular lymphoma of the duodenum with erosions as atypical macroscopic features. Case Rep Med. 2012;2012:582607. doi: 10.1155/2012/582607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akamatsu T, Kaneko Y, Ota H, Miyabayashi H, Arakura N, Tanaka E. Usefulness of double balloon enteroscopy and video capsule endoscopy for the diagnosis and management of primary follicular lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract in its early stages. Dig Endosc. 2010;22:33–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2009.00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kodama M, Kitadai Y, Shishido T, Shimamoto M, Fukumoto A, Masuda H, Tanaka S, Yoshihara M, Sakai A, Nakayama H, et al. Primary follicular lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract: a retrospective case series. Endoscopy. 2008;40:343–346. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakamura M, Ohmiya N, Hirooka Y, Miyahara R, Ando T, Watanabe O, Itoh A, Kawashima H, Ohno E, Kinoshita T, et al. Endoscopic diagnosis of follicular lymphoma with small-bowel involvement using video capsule endoscopy and double-balloon endoscopy: a case series. Endoscopy. 2013;45:67–70. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1325867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iddan G, Meron G, Glukhovsky A, Swain P. Wireless capsule endoscopy. Nature. 2000;405:417. doi: 10.1038/35013140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higuchi N, Sumida Y, Nakamura K, Itaba S, Yoshinaga S, Mizutani T, Honda K, Taki K, Murao H, Ogino H, et al. Impact of double-balloon endoscopy on the diagnosis of jejunoileal involvement in primary intestinal follicular lymphomas: a case series. Endoscopy. 2009;41:175–178. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1119467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakamura S, Matsumoto T, Umeno J, Yanai S, Shono Y, Suekane H, Hirahashi M, Yao T, Iida M. Endoscopic features of intestinal follicular lymphoma: the value of double-balloon enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2007;39 Suppl 1:E26–E27. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iwamuro M, Okada H, Kawano S, Shiode J, Takenaka R, Imagawa A, Inaba T, Suzuki S, Nishimura M, Mizuno M, et al. A multicenter survey of enteroscopy for the diagnosis of intestinal follicular lymphoma. Oncol Lett. 2015;10:131–136. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iwamuro M, Okada H, Takata K, Nose S, Miyatani K, Yoshino T, Yamamoto K. Diagnostic accuracy of endoscopic biopsies for the diagnosis of gastrointestinal follicular lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study of 48 patients. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2014;18:99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iwamuro M, Imagawa A, Kobayashi N, Kubota Y, Miyatani K, Takata K, Okada H. Synchronous adenocarcinoma and follicular lymphoma of the stomach. Intern Med. 2013;52:907–912. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.52.7948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferreira A, Gonçalves R, Rolanda C. A different kind of colon polyp. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1440, 1693–1694. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoshida N, Nomura K, Matsumoto Y, Nishida K, Wakabayashi N, Konishi H, Mitsufuji S, Kataoka K, Okanoue T, Taniwaki M. Detection of BCL2-IGH rearrangement on paraffin-embedded tissue sections obtained from a small submucosal tumor of the rectum in a patient with recurrent follicular lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2602–2604. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i17.2602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fehring A, Schmulewitz N. EUS-guided FNA diagnosis of recurrent follicular lymphoma in the transverse colon. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:652–653. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Esaki M, Matsumoto T, Nakamura S, Suekane H, Ohji Y, Yao T, Iida M. Capsule endoscopy findings in intestinal follicular lymphoma. Endoscopy. 2007;39 Suppl 1:E86–E87. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-945152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dalal L. Primary multifocal non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the colon successfully treated with chemotherapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:1005–1006; discussion 1006. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuroha M, Endo K, Sato Y, Shiga H, Kakuta Y, Takahashi S, Kinouchi Y, Shimosegawa T. Magnifying endoscopy findings in follicular lymphoma of the rectum using narrow band imaging. Endoscopy. 2011;43 Suppl 2 UCTN:E346–E347. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hiraide T, Shoji T, Higashi Y, Matsuda I, Terada T. Extranodal multiple polypoid follicular lymphoma of the sigmoid colon. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:182–184. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kakati BR, Krishna K, Krishna SG, Sharma SG, Sanathkumar N, Rego RF. Extensive extramedullary disease involving the colon in multiple myeloma: a case report and review of literature. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2012;43:379–381. doi: 10.1007/s12029-010-9199-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iwamuro M, Okada H, Takata K, Takenaka R, Inaba T, Mizuno M, Kobashi H, Tanaka S, Yoshioka M, Kondo E, et al. Colorectal Manifestation of Follicular Lymphoma. Intern Med. 2015:In press. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.55.5393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakase H, Matsuura M, Mikami S, Chiba T. Magnified endoscopic view of primary follicular lymphoma at the duodenal papilla. Intern Med. 2007;46:141–142. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.6229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Higuchi K, Komatsu K, Wakamatsu H, Kawasaki H, Murata M, Miyazaki K, Oikawa K, Ohwada M, Nanjo H, Otaka M, et al. Small intestinal follicular lymphoma with multiple tumor formations diagnosed by double-balloon enteroscopy. Intern Med. 2007;46:705–709. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.6087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Inoue N, Isomoto H, Shikuwa S, Mizuta Y, Hayashi T, Kohno S. Magnifying endoscopic observation of primary follicular lymphoma of the duodenum by using the narrow-band imaging system. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:158–159; discussion 159. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chowdhury M, Endo M, Chiba T, Kudara N, Oana S, Sato K, Akasaka R, Tomita K, Fujiwara S, Mizutani T, et al. Characterization of follicular lymphoma in the small intestine using double-balloon endoscopy. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2009;2009:835258. doi: 10.1155/2009/835258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Norimura D, Isomoto H, Niino D, Akazawa Y, Yamaguchi N, Ohnita K, Shikuwa S, Takeshima F, Nakao K. Magnified endoscopic observation with Fuji Intelligent Chromo Endoscopy of primary duodenal follicular lymphoma. Endoscopy. 2010;42 Suppl 2:E320–E321. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Norimura D, Isomoto H, Imaizumi Y, Akazawa Y, Matsushima K, Inoue N, Yamaguchi N, Ohnita K, Shikuwa S, Arima T, et al. Case series of duodenal follicular lymphoma, observed by magnified endoscopy with narrow-band imaging. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:428–434. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.03.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iwamuro M, Okuda M, Yumoto E, Suzuki S, Shirakawa A, Takata K, Yoshino T, Okada H, Yamamoto K. Magnifying endoscopy for intestinal follicular lymphoma is helpful for prompt diagnosis. Gut Liver. 2013;7:258–261. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2013.7.2.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iwamuro M, Okada H, Takata K, Kawai Y, Kawano S, Nasu J, Kawahara Y, Tanaka T, Yoshino T, Yamamoto K. Magnified endoscopic features of duodenal follicular lymphoma and other whitish lesions. Acta Med Okayama. 2015;69:37–44. doi: 10.18926/AMO/53120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iwamuro M, Okada H, Takata K, Fujii N, Kawano S, Kawahara Y, Yoshino T, Yamamoto K. Magnifying Endoscopic Observation of Duodenal Involvement of Follicular Lymphoma before and after Chemotherapy. Intern Med. 2015;54:1741–1745. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.54.4390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sentani K, Maeshima AM, Nomoto J, Maruyama D, Kim SW, Watanabe T, Kobayashi Y, Tobinai K, Matsuno Y. Follicular lymphoma of the duodenum: a clinicopathologic analysis of 26 cases. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008;38:547–552. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyn069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tzankov A, Hittmair A, Müller-Hermelink HK, Rüdiger T, Dirnhofer S. Primary gastric follicular lymphoma with parafollicular monocytoid B-cells and lymphoepithelial lesions, mimicking extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of MALT. Virchows Arch. 2002;441:614–617. doi: 10.1007/s00428-002-0670-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Montoto S, Davies AJ, Matthews J, Calaminici M, Norton AJ, Amess J, Vinnicombe S, Waters R, Rohatiner AZ, Lister TA. Risk and clinical implications of transformation of follicular lymphoma to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2426–2433. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.3260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miyata-Takata T, Takata K, Sato Y, Taniguchi K, Takahashi Y, Ohara N, Yoshino T. A case of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma transformed from primary duodenal follicular lymphoma. Pathol Int. 2014;64:527–532. doi: 10.1111/pin.12197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barrington SF, Mikhaeel NG, Kostakoglu L, Meignan M, Hutchings M, Müeller SP, Schwartz LH, Zucca E, Fisher RI, Trotman J, et al. Role of imaging in the staging and response assessment of lymphoma: consensus of the International Conference on Malignant Lymphomas Imaging Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3048–3058. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.5229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karam M, Novak L, Cyriac J, Ali A, Nazeer T, Nugent F. Role of fluorine-18 fluoro-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography scan in the evaluation and follow-up of patients with low-grade lymphomas. Cancer. 2006;107:175–183. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wirth A, Foo M, Seymour JF, Macmanus MP, Hicks RJ. Impact of [18f] fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography on staging and management of early-stage follicular non-hodgkin lymphoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Newman JS, Francis IR, Kaminski MS, Wahl RL. Imaging of lymphoma with PET with 2-[F-18]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose: correlation with CT. Radiology. 1994;190:111–116. doi: 10.1148/radiology.190.1.8259386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moog F, Bangerter M, Diederichs CG, Guhlmann A, Kotzerke J, Merkle E, Kolokythas O, Herrmann F, Reske SN. Lymphoma: role of whole-body 2-deoxy-2-[F-18]fluoro-D-glucose (FDG) PET in nodal staging. Radiology. 1997;203:795–800. doi: 10.1148/radiology.203.3.9169707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stumpe KD, Urbinelli M, Steinert HC, Glanzmann C, Buck A, von Schulthess GK. Whole-body positron emission tomography using fluorodeoxyglucose for staging of lymphoma: effectiveness and comparison with computed tomography. Eur J Nucl Med. 1998;25:721–728. doi: 10.1007/s002590050275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jerusalem G, Beguin Y, Najjar F, Hustinx R, Fassotte MF, Rigo P, Fillet G. Positron emission tomography (PET) with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) for the staging of low-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) Ann Oncol. 2001;12:825–830. doi: 10.1023/a:1011169332265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wöhrer S, Jaeger U, Kletter K, Becherer A, Hauswirth A, Turetschek K, Raderer M, Hoffmann M. 18F-fluoro-deoxy-glucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG-PET) visualizes follicular lymphoma irrespective of grading. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:780–784. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Iwamuro M, Okada H, Takata K, Shinagawa K, Fujiki S, Shiode J, Imagawa A, Araki M, Morito T, Nishimura M, et al. Diagnostic role of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography for follicular lymphoma with gastrointestinal involvement. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6427–636; discussion p.6434. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i44.6427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Paes FM, Kalkanis DG, Sideras PA, Serafini AN. FDG PET/CT of extranodal involvement in non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin disease. Radiographics. 2010;30:269–291. doi: 10.1148/rg.301095088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gutman F, Alberini JL, Wartski M, Vilain D, Le Stanc E, Sarandi F, Corone C, Tainturier C, Pecking AP. Incidental colonic focal lesions detected by FDG PET/CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:495–500. doi: 10.2214/ajr.185.2.01850495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lister TA, Crowther D, Sutcliffe SB, Glatstein E, Canellos GP, Young RC, Rosenberg SA, Coltman CA, Tubiana M. Report of a committee convened to discuss the evaluation and staging of patients with Hodgkin’s disease: Cotswolds meeting. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:1630–1636. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1989.7.11.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rohatiner A, d’Amore F, Coiffier B, Crowther D, Gospodarowicz M, Isaacson P, Lister TA, Norton A, Salem P, Shipp M. Report on a workshop convened to discuss the pathological and staging classifications of gastrointestinal tract lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 1994;5:397–400. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a058869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zucca E, Roggero E, Bertoni F, Cavalli F. Primary extranodal non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Part 1: Gastrointestinal, cutaneous and genitourinary lymphomas. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:727–737. doi: 10.1023/a:1008282818705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mir MA, Maurer MJ, Ziesmer SC, Slager SL, Habermann T, Macon WR, Link BK, Syrbu S, Witzig T, Friedberg JW, et al. Elevated serum levels of IL-2R, IL-1RA, and CXCL9 are associated with a poor prognosis in follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2015;125:992–998. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-06-583369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Iwamuro M, Shinagawa K, Okada H, Takata K, Yoshino T, Yamamoto K. Elevated soluble IL-2 receptor levels correlate with tumor bulk of follicular lymphomas with intestinal involvement. Clin Biochem. 2014;47:191–195. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2013.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Iwamuro M, Takenaka R, Mori A, Fujiki S, Miyake T, Asakura S, Okada H, Takata K, Yoshino T, Yamamoto K. Rapidly progressed primary intestinal follicular lymphoma with elevation of soluble interleukin-2 receptor levels. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2014;2014:549248. doi: 10.1155/2014/549248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Takata K, Sato Y, Nakamura N, Tokunaka M, Miki Y, Yukie Kikuti Y, Igarashi K, Ito E, Harigae H, Kato S, et al. Duodenal follicular lymphoma lacks AID but expresses BACH2 and has memory B-cell characteristics. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:22–31. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Toyoda H, Yamaguchi M, Nakamura S, Nakamura T, Kimura M, Suzuki H, Mukai K, Sawa H, Kawamura K, Shiku H. Regression of primary lymphoma of the ampulla of Vater after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:92–96. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.114963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hayashi H, Onishi Y, Mitsuoka H, Ogura T, Maeda M, Nishigami T, Harada M. Regression of follicular lymphoma of the duodenum following eradication of H. pylori infection. Intern Med. 2013;52:2611–2614. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.52.0552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yaguchi T, Imaeda H, Kizaki M, Hosoe N, Suzuki H, Ogata H, Iwao Y, Kameyama K, Ikeda Y, Hibi T. Partial regression of duodenal lesions of intestinal follicular lymphoma after antibiotic treatment. Dig Endosc. 2010;22:316–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2010.01011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Iwamuro M, Okada H, Shinagawa K, Takata K, Yoshino T, Yamamoto K. Regression of duodenal follicular lymphoma: susceptible to H. pylori eradication? Intern Med. 2014;53:1397. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.53.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nooka AK, Nabhan C, Zhou X, Taylor MD, Byrtek M, Miller TP, Friedberg JW, Zelenetz AD, Link BK, Cerhan JR, et al. Examination of the follicular lymphoma international prognostic index (FLIPI) in the National LymphoCare study (NLCS): a prospective US patient cohort treated predominantly in community practices. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:441–448. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Arcaini L, Merli M, Passamonti F, Rizzi S, Ferretti V, Rattotti S, Pascutto C, Paulli M, Lazzarino M. Validation of follicular lymphoma international prognostic index 2 (FLIPI2) score in an independent series of follicular lymphoma patients. Br J Haematol. 2010;149:455–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.08065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Montoto S, López-Guillermo A, Altés A, Perea G, Ferrer A, Camós M, Villela L, Bosch F, Esteve J, Cervantes F, et al. Predictive value of Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI) in patients with follicular lymphoma at first progression. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1484–1489. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Giné E, Montoto S, Bosch F, Arenillas L, Mercadal S, Villamor N, Martínez A, Colomo L, Campo E, Montserrat E, et al. The Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI) and the histological subtype are the most important factors to predict histological transformation in follicular lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1539–1545. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]