Abstract

Extreme learning machine (ELM) is a novel and fast learning method to train single layer feed-forward networks. However due to the demand for larger number of hidden neurons, the prediction speed of ELM is not fast enough. An evolutionary based ELM with differential evolution (DE) has been proposed to reduce the prediction time of original ELM. But it may still get stuck at local optima. In this paper, a novel algorithm hybridizing DE and metaheuristic coral reef optimization (CRO), which is called differential evolution coral reef optimization (DECRO), is proposed to balance the explorative power and exploitive power to reach better performance. The thought and the implement of DECRO algorithm are discussed in this article with detail. DE, CRO and DECRO are applied to ELM training respectively. Experimental results show that DECRO-ELM can reduce the prediction time of original ELM, and obtain better performance for training ELM than both DE and CRO.

Keywords: Extreme learning machine (ELM), Differential evolution (DE), Coral reef optimization (CRO), Differential evolution coral reef optimization (DECRO)

Introduction

Recently, the modeling of cognitive processes has been widely dicussed and many researchers has been attracted to study the related learning algorithms (Wang et al. 2013; Wennekers and Palm 2009; Lee et al. 2012; Chowdhury et al. 2015). Among the cognitive based machine learning algorithms, extreme learning machine (ELM) (Huang et al. 2004) is a novel and fast learning method based on the structure of single layer feed-forward network. During the training process of ELM, the input layer parameters of a SLFN are randomly set without optimization, and the output layer weight is calculated by Moore–Penrose (MP) generalized inverse without iteration. According to this idea, ELM could not only become extremely faster than the traditional gradient-based algorithms, but also avoid being stuck at local optimization and obtain artificial neural network (ANN) models with better generalization performance. However, without the optimized input layer weights and bias, more hidden layer nodes are needed to improve the performance of ELM and it brings about the slow prediction speed of ELM. Zhu et al. (2005) proposed the evolutionary ELM (E-ELM), where the input layer weight and bias is learnt using differential evolution (DE), so as to combine the global optimization power of evolutionary computing and the efficiency of ELM training method which can enhance the prediction speed of ELM and get compact networks.

The DE (Storn and Price 1997) algorithm used in E-ELM to train the input layer parameters is well-known for its global optimization ability and efficiency to locate the global solutions. The reason that DE has been applied to a wild range of science and engineering (Roque and Martins 2015; Bhadra and Bandyopadhyay 2015; Hamedia et al. 2015; Chena et al. 2015; Atif and Al-Sulaiman 2015; Garcła-Domingo et al. 2015; Sarkara et al. 2015) is that it is simple and straightforward to be implemented, and that the parameters of DE which needed to be tuned manually are very few. However, it was pointed out that DE may get stuck at local optima for some problem (Ronkkonen et al. 2005) and doesnt perform well on problems that are not linear separable (Langdon and Poli 2007). In the standard DE new individuals are generated with the information of different individuals which may leads to good explorative global searching power, but the local searching power near each individual especially the best ones is relatively poor. An early published paper about evolutionary programming (Birru et al. 1999) also indicated that local searching helps to generate global optimum if the corresponding algorithm could find the basin of attraction for global optimum and thus reduce the time for the algorithm to converge. Thus the explorative power and exploitive power should be balanced to reach better performance. In this sense, we develop a novel algorithm differential evolution coral reef optimization (DECRO) by hybridizing DE and a novel metaheuristic coral reef optimization (CRO) (Salcedo-Sanz et al. 2014a). CRO algorithm is a metaheuristic modeling and simulating coral reproduction, which employs both a mutation process to avoid local optima and a exploitive process which is similar to simulated annealing. All three mentioned algorithms i.e. DE, CRO, DECRO, inspired by the framework of E-ELM, are applied to training ELM input layer parameters. The corresponding approaches are denoted as DE-ELM, CRO-ELM, DECRO-ELM respectively.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: “DE algorithm and CRO algorithm” section briefly introduces DE and CRO, “DECRO-the proposed algorithm” section proposes the DECRO algorithm, “Apply DECRO to training ELM” section introduces the original ELM and application of DECRO to train ELM (i.e. DECRO-ELM). “Experiments” section presents the experimental results and conclusions.

DE algorithm and CRO algorithm

Differential evolution (DE) algorithm

DE, proposed by Storn and Price (1997), is a powerful search algorithm in the optimal problems, and uses the vector differences of individuals for perturbing the population members.

Outline of DE

As an initial setting, DE employs a population Pop of N individuals, each of which representing a D dimensional solution vector denoted as . At the beginning of DE, each individual is randomly generated in the search space. During the process of DE algorithm, new individuals with better objective function value are generated by iterations of three fundamental operations (i.e. mutation, crossover and selection), until a certain stop criteria is reached.

Mutation

During mutation, a new donor vector is generated as a candidate for each individual of the current population Pop as (1).

| 1 |

where r1, r2, r3 are randomly chosen individual indexes ranging from 1 to , each of which is different from the others, F is the scaling factor that indicates the weight of the difference of individuals.

Crossover

With the generated donor vector and the original individual , a trial vector is generated by binomial crossover as follows.

| 2 |

where CR denotes the crossover probability for each dimension, rand is a random number subjects to uniform distribution U(0, 1), is a randomly generated integer ranging from 1 to D ( the dimensionality of the fitness function).

Selection

For each of the individuals in the current population, the trail vector is compared with the original individual and only the one with better objective function value will be incorporated into the population of the next generation.

| 3 |

where denotes the ith individual for the population of the next generation and f(.) is the fitness function (objective function).

Coral reef optimization (CRO) metaheuristic algorithm

CRO is a novel algorithm proposed by Salcedo-Sanz et al. (2014a), tackling optimization problems by modeling and simulating corals reproduction and formation. A series of corresponding application has been carried out (Salcedo-Sanz et al. 2014a, b, c, d, e, 2015, 2013). The main processes of CRO is described as follows.

Terminology and notations

Let be a model of reef, consisting of a square grid. We assume that each square (i, j) of is able to allocate a coral (or colony of corals), representing different solutions to our problem, encoded as strings of numbers in a given alphabet . The CRO algorithm is first initialized at random by assigning some squares in to be occupied by corals (i.e. solutions to the problem) and some other squares in the grid to be empty, which means holes in the reef where new corals can freely settle and grow. The rate between free/total squares at the beginning of the algorithm is an important parameter of the CRO algorithm, which will be denoted in what follows as . Each coral is labeled with an associated fitness function that represents the problems objective function. Note that the reef will progress as long as healthier (stronger) corals (which represent better solutions to the problem at hand) survive, while less healthy corals perish.

Partition of the existed corals

A certain fraction (denoted as ) of existed corals is selected uniformly at random to be broadcast spawners, while the remaining existed coral (at a fraction of 1 − ) is selected to be Brooders.

Broadcast spawning (crossover)

Select couples out from the pool of broadcast spawners in each iteration, each of which will form a coral larva by crossover, which is then released out to the water (see “Larvae setting (competition for a living space)” section). Note that, once two corals have been selected to be the parents of a larva, they are not chosen anymore in an iteration (i.e. two corals are parents only once in a given iteration). This couple selection can be done uniformly at random or by resorting to any fitness proportionate selection approach (e.g. roulette wheel).

Brooding (mutation for local searching)

For all brooders, the brooding modeling consists of the formation of a coral larva by means of a random mutation of the brooding-reproductive coral (self-fertilization considering hermaphrodite corals). The produced larva is then released out to the water in a similar fashion as that of the larvae generated in “Depredation in polyp phase (eliminate corals with poor fitness value)” section.

Larvae setting (competition for a living space)

Once all the larvae are formed, either through broadcast spawning or by brooding, they will try to set and grow in the reef. Each larva will randomly try, for a given number of times (denoted as k), to set in a square of the reef. If the square is empty (free space in the reef), the coral grows therein. By contrast, if a coral is already occupying the square at hand, the new larva will set only if its fitness function is better than that of the existing coral. Finally, for a given brooder, if all of the k trials are failed, it will be eliminated.

Asexual reproduction (budding)

In the modeling of asexual reproduction (budding or fragmentation), the overall set of existing corals in the reef are sorted by the corresponding fitness value [given by ], from which a fraction duplicates itself and tries to settle in a different part of the reef by following the setting process described in “Larvae setting (competition for a living space)” section.

Depredation in polyp phase (eliminate corals with poor fitness value)

At the end of iteration, a small number of corals in the reef can be depredated, thus liberating space in the reef for next coral generation. The depredation operator is applied with a very small probability at each iteration, and exclusively to a fraction of the worse fitness corals. Note that any coral can be repeated for at most times in the reef, otherwise the redundant repetitions will be eliminated and the corresponding square is released.

The processes described in “Partition of the existed corals”–“Depredation in polyp phase (eliminate corals with poor fitness value)” sections are repeated iteratively until certain stop criteria is reached.

DECRO-the proposed algorithm

According to Salcedo-Sanz et al. (2014a), the explorative power of CRO is controlled by broadcast spawning which carry out the majority of global searching and brooding which could help jump out of the local optima. As for exploitive power, the budding process ensures that CRO carefully searches the neighbor of the current Pop and larvae setting process controls local searching by a simulated annealing like process, the cooling temperature of which is controlled by . To better balance the explorative/exploitive power, we propose a hybrid algorithm called DECRO, where DE is used to carry out the broadcast spawning. In such a manner, DE algorithm could enhance the explorative power of CRO, while CRO could render exploitive power to DE. Details of DECRO is described as follows.

Comparing with the original CRO, the broadcast spawning, budding and depredation process are improved as follows.

Improved partition:

Instead of selecting the broadcast spawners uniformly at random, selects the 1 − percent of existed corals with better fitness value as brooders to enhance the local searching power around the top candidates, while the other percent of existed corals as broadcast spawners to explore the solution space, could be tuned as a function of iteration time to further enhance the dynamic performance of DECRO.

Improved broadcastspawning:

During one step of , a larva candidate is generated for each coral belonging to the set of current spawners spawner by DE and only the larvae outperform their ancestor are included in the set of selected larvae . The formal expression is discussed in Algorithm 1.

Improved budding:

During one step of , to enhance local searching power,instead of simply copying the top Fa corals, an extra Cauchy mutation is carried out [generate a random number subjects to Cauchy distribution with parameter denoted randc] for each of the top Fa corals. The merge of mutated coral and their ancestors form the candidate larvae set , only half of with better fitness function value survive and will struggle for their living space by “Larvae setting (competition for a living space)” section. The formal expression is discussed in Algorithm 2.

Improved depredation:

In , not a coral is eliminated and a novel strategy to deal with redundant repetitions is proposed. Instead of eliminate the redundant coral, a local searching is carried out in , by which the redundant coral will be replaced.

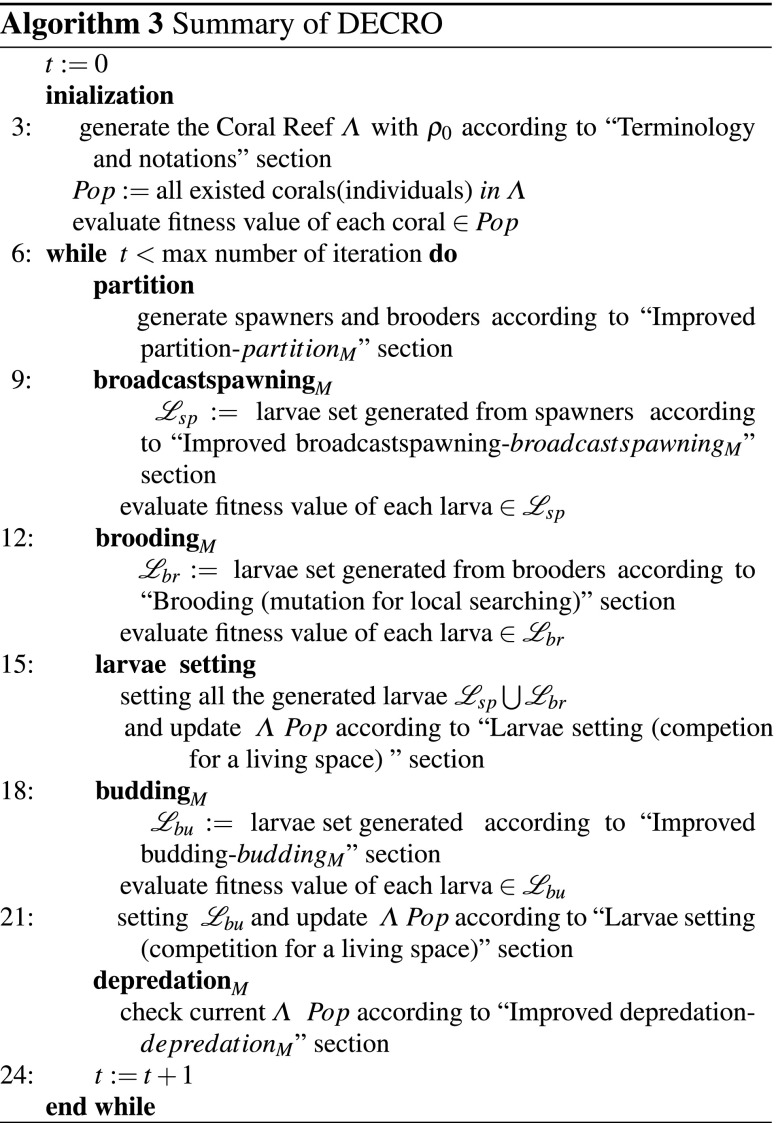

The outline of DECRO is summarized as the following pseudo-code.

Apply DECRO to training ELM

Similar to traditional ANN, during training phase of ELM, the output layer is calculated with the training examples, while during prediction phase, unknown examples are given to ELM, the predicted output is calculated based on the trained ELM model.

Review of original ELM training

The original ELM training method is summarized as follows.

Given a training set is the ith input vector, is the ith target vector and an activation function g(x) and the number of hidden nodes is denoted as .

-

Calculate the hidden layer output matrix

4 where are d dimensional column vectors which are randomly generated without optimization.

Let b be , for siplicity we define (i.e. the generalized weight), and where hence after. The hidden matrix H can then be denoted as G(XW).

-

2.

Estimate the output layer weight by following equation

5 where T is the target vector .

Owing to the random generalization of W, the whole training process could be finished without iteration, which makes training ELM much faster than training traditional gradient based ANN algorithms. However such training process needs much larger nh than used in traditional training process (the number of hidden layer nodes) which may retard the prediction speed.

Influence of nh on the prediction efficiency of ELM

To better understand how nh affects ELM prediction, the computational complexity of ELM prediction for invisible examples needs to further discussed. Algorithm 4 shows the procedure of ELM to predict the output for unknown test examples where m is number of examples in , d is the dimension of each example, nh is the number of hidden layer neurons, is the number of output layer neurons (i.e.the dimensionality of the output of each example) and is the predicted output. According to the prediction algorithm, the total computational complexity depends on the calculation of H and and we have Eq. (6).

| 6 |

Firstly, to calculate H, the matrix multiplication which takes is carried out followed with the calculation of the activation function G which takes , where is the complexity for , together we have . Secondly, to obtain , only a simple matrix multiplication is needed which takes . Above all, we have

| 7 |

It is obvious that nh dominates when nh becomes extremely large. For original ELM, the hidden layer weights are randomly generated without any optimization procedure, in consequence, much larger nh is needed to remain the same accuracy as classical neural network training algorithm such as BP. From the aforementioned discussion, such feature may significantly slow down the response speed of ELM to predict unknown examples. In order to balance the training efficiency and prediction efficiency, optimization techniques could be embedded into the training procedure of ELM.

Training ELM based on DECRO

To improve prediction efficiency of ELM discussed in “Influence of nh on the prediction efficiency of ELM” section, the evolutionary framework of ELM (E-ELM) was first proposed by Zhu et al. (2005) which could reduce the hidden layer nodes of original ELM while preserves the efficiency of original ELM at the same time. In Zhu et al. (2005), the input layer parameters are trained by DE and the output layer weights are calculated as the original algorithm. The formal expression of E-ELM is presented in Algorithm 5.

In order to develop a better evolutionary algorithm to be embedded into the E-ELM framework mentioned above, we apply DECRO to train ELM and the corresponding training algorithm denotes DECRO-ELM where DECRO is used to optimize W and b which works as follows.

As illustrated by Figs. 1 and 2, the solution vector for a existed coral located at grid(i, j) mentioned at “Terminology and notations” section in DECRO-ELM is the vectorization of generalized weight denoted as , is calculated using as “Review of original ELM training” section and fitness function of a coral is defined as the mean square error (MSE) of training set sampled from , input weight W is solved by DECRO according Algorithm 5 by changing DE to DECRO.

Fig. 1.

An individual in DECRO-ELM is excatly a vecter coding for the input layer weight

Fig. 2.

After transforming to matrix, an ELM model is trained for each individual and the fitness function is exactly the mse for such ELM

Experiments

To test the effectiveness of the purposed algorithm, DE and CRO are embedded to E-ELM framework, which denoted as DE-ELM and CRO-ELM thereafter. The performances of DECRO-ELM, DE-ELM, CRO-ELM, original ELM with larger hidden nodes on four real world datasets for regression problem are tested with each algorithm run for 30 times for each dataset. The one way ANOVA statistical analysis is employed to further measure the statistical significance of performance difference. For experiments with variance homogeneity, LSD Hayter (1986) is used as the pairwise comparison of performance, and Dunnett T3 (1955) is employed otherwise. SPSS 19.0 is used to carry out these experiments. Aimed at proofing the prediction efficiency of the purposed algorithm, the running time of each algorithm to predict the test set for each dataset over 30 times is tested, with mean value of which recorded.

Parameters setting

- Data set separation:

#training set /#test set ratio for all data sets tested in this paper is set to 80%/20%.

- DE-ELM:

for DE, we set F = 0.7, CR = 0.1, = 10

- CRO-ELM:

N = 5, M = 2, Fb linearly decreases 1 from 0.9 to 0.4, Fa = 0.2, Fd = 0.1, k = 2, = 0.3

- DECRO-ELM:

the parameter settings for DECRO-ELM is simply the combination of that of DE-ELM and CRO-ELM.

For all three E-ELMs the function evaluation times is set as 200. To simplify the expressions all X-ELM (X = DECRO,DE, CRO) will be denoted as X in the following tables. Note that all the examples in each dataset is normalized to interval [0,1].

Bike sharing dataset

The bike sharing dataset was published by Hadi Fanaee-T at Laboratory of Artificial Intelligence and Decision Support (LIAAD), University of Porto (http://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/Bike+Sharing+Dataset) which can be obtained from http://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/Bike+Sharing+Dataset, The goal of this dataset is to monitor the mobility in a city utilizing data recorded by bike sharing systems, with a daily monitored and hourly monitored dataset, only the daily monitored dataset (day.csv) is used. To reduce redundancy, two attributes called casual and registered are removed. The basic information and the nh parameter for four algorithms are described as Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of bike sharing dataset

| Training set size | 13,911 |

| Test set size | 3478 |

| Number of attributes | 16 |

| n h for E-ELMs | 12 |

| n h for original ELM | 30 |

The statistical summary of MSE for DECRO-ELM DE-ELM,CRO-ELM and ELM is recorded as Table 2, and the one way ANOVA result is recorded as Tables 3, 4 and 5. Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5 show that on the training set, the mean MSE of the purposed DECRO-ELM algorithm is significantly better than all three other algorithms except ELM with larger hidden layer nodes, while on the test set, the mean MSE of the purposed DECRO-ELM algorithm with 12 hidden layer nodes is significantly better than all three other algorithms except CRO.

Table 2.

MSE statistics for bike sharing dataset

| Mean | Min | Max | SD | Median | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | |||||

| DECRO | 7.089 | 6.573 | 7.717 | 0.2480 | 7.083 |

| DE | 8.196 | 7.523 | 8.737 | 0.2748 | 8.201 |

| CRO | 7.601 | 6.980 | 8.367 | 0.3761 | 7.605 |

| ELM | 7.240 | 6.476 | 8.317 | 0.4195 | 7.183 |

| Test | |||||

| DECRO | 8.058 | 7.345 | 9.323 | 0.4710 | 8.022 |

| DE | 10.58 | 9.136 | 13.29 | 0.9633 | 10.54 |

| CRO | 8.461 | 7.420 | 11.13 | 0.8592 | 8.302 |

| ELM | 10.69 | 8.791 | 13.63 | 0.9650 | 10.73 |

The bolded data highlights the best result for each metric with ANOVA test with p < 0.05

Table 3.

Test for variance homogeneity for bike sharing dataset

| Levene statistics | df1 | df2 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | 3.399 | 3 | 116 | 0.020 |

| Test | 3.686 | 3 | 116 | 0.014 |

Table 4.

ANOVA test for bike sharing data set

| F | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Train | 61.927 | 0.000 |

| Test | 78.595 | 0.000 |

Table 5.

Pairwise comparison for bike sharing data set

| Comparison method | Alg i | mse i − mse | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | Dunnett T3 | DE | 0.00110* | 0.000 |

| CRO | 0.00051* | 0.000 | ||

| ELM | 0.00015 | 0.459 | ||

| Test | Dunnett T3 | DE | 0.00252* | 0.000 |

| CRO | 0.00040 | 0.171 | ||

| ELM | 0.00263* | 0.000 |

mse, the mse performance of DECRO-ELM

* p < 0.05

Concrete compressive strength data set

This data was published in Yeh (1988), which can be obtained from http://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/Concrete+Compressive+Strength and is used to model the compressive strength of high performance concrete based on features like water-to-cement ratio and the content of other cement ingredients. The basic information and the nh parameter for four algorithms are described as Table 6.

Table 6.

Summary of concrete compressive strength data set

| Training set size | 826 |

| Test set size | 207 |

| Number of attributes | 9 |

| n h for E-ELMs | 30 |

| n h for original ELM | 60 |

The statistical summary of MSE for DECRO-ELM DE-ELM, CRO-ELM and ELM is recorded as Tables 7, 8, 9 and 10, and the one way anova result is recorded as Tables 7, 8, 9 and 10. The data from Tables 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 indicate that the mean MSE of DECRO-ELM is significantly better than all there other algorithms on both the training set and test set.

Table 7.

MSE statistics for concrete compressive strength data set

| Mean | Min | Max | SD | Median | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | |||||

| DECRO | 7.144 | 6.395 | 8.184 | 0.4023 | 7.081 |

| DE | 8.635 | 8.310 | 8.976 | 0.1519 | 8.645 |

| CRO | 7.713 | 6.889 | 8.594 | 0.4644 | 7.672 |

| ELM | 7.511 | 6.437 | 8.280 | 0.4348 | 7.574 |

| Test | |||||

| DECRO | 8.372 | 6.741 | 10.003 | 0.7606 | 8.454 |

| DE | 10.21 | 9.241 | 11.83 | 0.6348 | 10.21 |

| CRO | 8.945 | 7.396 | 10.81 | 0.8385 | 8.930 |

| ELM | 9.189 | 6.629 | 11.47 | 0.8943 | 9.260 |

The bolded data highlights the best result for each metric with ANOVA test with p < 0.05

Table 8.

Test for variance homogeneity for concrete compressive strength data set

| Levene statistics | df1 | df2 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | 6.408 | 3 | 116 | 0.000 |

| Test | 0.759 | 3 | 116 | 0.519 |

Table 9.

ANOVA test for concrete compressive strength data set

| F | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Train | 79.255 | 0.000 |

| Test | 27.586 | 0.000 |

Table 10.

Pairwise comparison for concrete compressive strength data set

| Comparison method | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | Dunnett T3 | DE | 0.00149* | 0.000 |

| CRO | 0.00056* | 0.000 | ||

| ELM | 0.00036 | 0.009 | ||

| Test | LSD | DE | 0.00183* | 0.000 |

| CRO | 0.00057 | 0.007 | ||

| ELM | 0.00081* | 0.000 |

mse, the mse performance of DECRO-ELM

* p < 0.05

Housing data set

This dataset is recorded by Harrison and Rubinfeld in http://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/Housing to predict the MEDV (i.e. median value of Median value of owner-occupied homes per $1000), the reader is referred to (Belsley et al. 1980; Quinlan 1993) for more details. The basic information and the nh parameter for all algorithms are described as Table 11.

Table 11.

Summary of housing data set

| Training set size | 405 |

| Test set size | 101 |

| Number of attributes | 14 |

| n h for E-ELMs | 12 |

| n h for original ELM | 25 |

The statistics for MSE for DECRO-ELM DE-ELM, CRO-ELM and ELM are recorded as Table 12, and the one way ANOVA result is recorded as Tables 13, 14 and 15. Together with Tables 12, 13, 14 and 15, it is concluded that the mean MSE of DECRO-ELM is significantly better than that of CRO-ELM, and is not significantly different with DE-ELM and CRO-ELM on both the training set and test set, but the minimum and maximum MSE for DECRO-ELM are slightly better than all three other algorithms on both training and test set.

Table 12.

MSE statistics for housing data set

| Mean | Min | Max | SD | Median | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | |||||

| DECRO | 8.341 | 6.831 | 9.351 | 0.5895 | 8.422 |

| DE | 8.645 | 7.338 | 9.438 | 0.5273 | 8.767 |

| CRO | 9.386 | 7.993 | 10.55 | 0.5989 | 9.504 |

| ELM | 8.718 | 7.028 | 11.28 | 1.082 | 8.564 |

| Test | |||||

| DECRO | 10.42 | 7.106 | 15.84 | 1.795 | 10.32 |

| DE | 10.76 | 8.316 | 14.23 | 1.425 | 10.62 |

| CRO | 11.79 | 9.318 | 13.75 | 0.9624 | 11.86 |

| ELM | 10.73 | 7.777 | 16.37 | 1.802 | 10.81 |

The bolded data highlights the best result for each metric with ANOVA test with p < 0.05

Table 13.

Test for variance homogeneity for housing data set

| Levene statistics | df1 | df2 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | 5.726 | 3 | 116 | 0.001 |

| Test | 2.686 | 3 | 116 | 0.050 |

Table 14.

ANOVA test for housing data set

| F | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Train | 10.424 | 0.000 |

| Test | 4.356 | 0.006 |

Table 15.

Pairwise comparison for housing data set

| Comparison method | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | Dunnett T3 | DE | 0.00030* | 0.231 |

| CRO | 0.00104* | 0.000 | ||

| ELM | 0.00037 | 0.480 | ||

| Test | Dunnett T3 | DE | 0.00033* | 0.962 |

| CRO | 0.00136 | 0.005 | ||

| ELM | 0.00031* | 0.984 |

mse, the mse performance of DECRO-ELM

* p < 0.05

Yacht hydrodynamics data set

This dataset (Gerritsma et al. 1981; Ortigosa et al. 2007) is donated by Roberto Lopez, from Ship Hydromechanics Laboratory, which can be obtained from [32], Maritime and Transport Technology Department, Technical University of Delft, aimed at predicting residuary resistance of sailing yachts by features like basic hull dimensions and the boat velocity. The yacht hydrodynamics data set 308 full-scale experiments, which were performed at the Delft Ship Hydromechanics Laboratory for that purpose. The basic information and the nh parameter for four algorithms are described as Table 16. The statistics of MSE for DECRO-ELM DE-ELM,CRO-ELM and ELM is recorded as Table 17, and the one way ANOVA result is recorded as Tables 18, 19 and 20. Form the experiment results, it is concluded that on the training set the mean MSE of DECRO-ELM with 40 hidden layer nodes is significantly better than that of all three algorithms except ELM with 80 hidden layer nodes, while on the test set, the MSE for DECRO-ELM is significantly better than all three other algorithms. The large difference between the training and test set result of ELM also shows that ELM is prone to overfit the training set by employing a larger number of hidden layer nodes which may increase the model complexity.

Table 16.

Summary of yacht hydrodynamics data set

| Training set size | 247 |

| Test set size | 61 |

| Number of attributes | 7 |

| n h for E-ELMs | 40 |

| n h for original ELM | 80 |

Table 17.

MSE statistics for yacht hydrodynamics data set

| Mean | Min | Max | SD | Median | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | |||||

| DECRO | 0.1555 | 0.09930 | 0.2183 | 0.03265 | 0.1573 |

| DE | 1.436 | 0.9108 | 1.950 | 0.2753 | 1.392 |

| CRO | 0.2174 | 0.1329 | 0.3981 | 0.07310 | 0.1864 |

| ELM | 0.1763 | 0.09655 | 0.3679 | 0.07386 | 0.1447 |

| Test | |||||

| DECRO | 0.2615 | 0.1150 | 0.4340 | 0.07623 | 0.2636 |

| DE | 2.519 | 1.159 | 4.061 | 0.6966 | 2.439 |

| CRO | 0.3582 | 0.1933 | 0.8077 | 0.1348 | 0.2878 |

| ELM | 1.054 | 0.4195 | 2.272 | 0.4878 | 0.9814 |

The bolded data highlights the best result for each metric with ANOVA test with p < 0.05

Table 18.

Test for variance homogeneity for yacht hydrodynamics data set

| Levene statistics | df1 | df2 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | 34.657 | 3 | 116 | 0.000 |

| Test | 27.924 | 3 | 116 | 0.000 |

Table 19.

ANOVA test for yacht hydrodynamics data set

| F | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| train | 520.870 | 0.000 |

| test | 168.639 | 0.000 |

Table 20.

Pairwise comparison for yacht hydrodynamics data set

| Comparison method | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | Dunnett T3 | DE | 0.00128* | 0.000 |

| CRO | 0.00006* | 0.001 | ||

| ELM | 0.00002 | 0.662 | ||

| Test | Dunnett T3 | DE | 0.00225* | 0.000 |

| CRO | 0.00009 | 0.009 | ||

| ELM | 0.00079* | 0.000 |

mse, the mse performance of DECRO-ELM

* p < 0.05

Summary of the experiment results

According to Table 21, for most of all 8 comparisons (test and train set for each dataset), DECRO-ELM significantly outperforms both of its ancestors, and the performance of DECRO-ELM is at least no worse than the original ELM with larger hidden nodes. The average prediction time for all of the four datasets in Table 22 shows that all three E-ELMs can reach a faster prediction speed than the original one. As a summary of all the experimental results, DECRO-ELM could improve the performance of DE-ELM and CRO-ELM and enhance the prediction speed of the original ELM.

Table 21.

Summary of the experiment result

| DECRO outperforms i | DECRO performs as well as i | DECRO performs worse | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DE | 6 | 2 | 0 |

| CRO | 7 | 1 | 0 |

| ELM with larger n h | 4 | 4 | 0 |

Table 22.

Average prediction time test

| Data set | DECRO | DE | CRO | ELM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bike Sharing | 0.525 | 0.696 | 0.476 | 1.41 |

| Concrete | 0.895 | 1.150 | 0.973 | 2.49 |

| Housing | 0.250 | 0.322 | 0.239 | 0.763 |

| Yacht | 0.608 | 1.100 | 0.6.31 | 1.53 |

Conclusions

In this paper we have proposed a novel hybrid algorithm DECRO that combines the differential evolution with coral reefs optimization approach. The resulting DECRO algorithm has been further applied for training the input layer parameters of extreme machine learning for ANN, which is called DECRO-ELM. Based on data from four real world regression problems, it has been shown that the proposed DECRO-ELM algorithm obtains good prediction precision and rapider prediction results than its ancestors: ELM, DE-ELM and CRO-ELM.

Acknowledgments

This paper is sponsored by the Scientific Research Foundation for the Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars, National Key Technology R&D Program in 12th Five-year Plan of China (No. 2013BAI13B06).

Footnotes

To make change dynamically, we set , where t is the current iteration number, is the total iteration number.

References

- Atif M, Al-Sulaiman FA. Optimization of heliostat field layout in solar central receiver systems on annual basis using differential evolution algorithm. Energy Convers Manag. 2015;95:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.enconman.2015.01.089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belsley DA, Kuh E, Welsch RE. Regression diagnostics: identifying influential data and sources of collinearity. Hoboken: Wiley; 1980. pp. 244–261. [Google Scholar]

- Bhadra T, Bandyopadhyay S. Unsupervised feature selection using an improved version of differential evolution. Expert Syst Appl. 2015;42:4042–4053. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2014.12.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birru HK, Chellapilla K, Rao SS (1999) Local search operators in fast evolutionary programming. In: Proceedings of the IEEE into Congress on Evolutionary Computation, pp 1506–1513

- Chena Y, Mahalecb V, Chena Y, Liua X, Hea R, Suna K. Reconfiguration of satellite orbit for cooperative observation using variable-size multi-objective differential evolution. Eur J Oper Res. 2015;242:10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejor.2014.09.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury AR, Chetty M, Evans R (2015) Stochastic S-system modeling of gene regulatory network. Cogn Neurodyn 9:535–547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dunnett CW. A multiple comparison procedure for comparing several treatments with a control. J Am Stat Assoc. 1955;50:1096–1121. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1955.10501294. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fanaee-T H, Gama J. Event labeling combining ensemble detectors and background knowledge. Progress in artificial intelligence. Berlin: Springer; 2013. pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Garcła-Domingo B, Carmona CJ, Rivera-Rivas AJ, del Jesus MJ, Aguilera J. A differential evolution proposal for estimating the maximum power delivered by CPV modules under real outdoor conditions. Expert Syst Appl. 2015;42:5452–5462. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2015.02.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsma J, Onnink R, Versluis A. Geometry, resistance and stability of the delft systematic yacht hull series. Int Shipbuild Prog. 1981;28:276–297. [Google Scholar]

- Hamedia N, Iranshahib D, Rahimpoura MR, Raeissia S, Rajaeia H. Development of a detailed reaction network for industrial upgrading of heavy reformates to xylenes using differential evolution technique. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng. 2015;48:56–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jtice.2014.10.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayter AJ. The maximum familywise error rate of fisher’s least significant difference test. J Am Stat Assoc. 1986;81:1000–1004. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1986.10478364. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- http://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/Yacht+Hydrodynamics

- Huang G-B, Zhu Q-Y, Siew C-K (2004) Extreme learning machine: a new learning scheme of feedforward neural networks. In: Proceedings of the international joint conference on neural networks (IJCNN2004), pp 25–29

- Langdon WB, Poli R. Evolving problems to learn about particle swarm optimizers and other search algorithms. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2007;11:561–578. doi: 10.1109/TEVC.2006.886448. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S-Y, Song H-A, Amari S. A new discriminant NMF algorithm and its application to the extraction of subtle emotional differences in speech. Cogn Neurodyn. 2012;6(6):525–535. doi: 10.1007/s11571-012-9213-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortigosa I, Lopez R, Garcia J (2007) A neural networks approach to residuary resistance of sailing yachts prediction. In: Proceedings of the international conference on marine engineering MARINE

- Quinlan R (1993) Combining instance-based and model-based learning. In: Proceedings on the tenth international conference of machine learning, pp 236–243

- Ronkkonen J, Kukkonen S, Price KV (2005) Real parameter optimization with differential evolution. In: Proceedings of IEEE CEC, vol 1. pp 506–513

- Roque CMC, Martins PALS. Differential evolution optimization for the analysis of composite plates with radial basis collocation meshless method. Compos Struct. 2015;75:317–326. doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2015.01.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salcedo-Sanz S, Gallo-Marazuela D, Pastor-Snchez A, Carro-Calvo L, Portilla-Figueras A, Prieto L. Offshore wind farm design with the coral reefs optimization algorithm. Renew Energy. 2014;63:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2013.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salcedo-Sanz S, Pastor-Snchez A, Prieto L, Blanco-Aguilera A, Garcła-Herrera R. Feature selection in wind speed prediction systems based on a hybrid coral reefs optimization—extreme learning machine approach. Energy Convers Manag. 2014;87:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.enconman.2014.06.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salcedo-Sanz S, Casanova-Mateo C, Pastor-Snchez A, Snchez CGirn M. Daily global solar radiation prediction based on a hybrid coral reefs optimization—extreme learning machine approach. Solar Energy. 2014;105:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.solener.2014.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salcedo-Sanz S, Garcia-Diaza P, Portilla-Figueras JA, Del Ser J, Gil-Lopez S. A coral reefs optimization algorithm for optimal mobile network deployment with electromagnetic pollution control criterion. Appl Soft Comput. 2014;24:239–248. doi: 10.1016/j.asoc.2014.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salcedo-Sanz S, Pastor-Sanchez A, Del Ser J, Prieto L, Geem ZW. A coral reefs optimization algorithm with harmony search operators for accurate wind speed prediction. Renew Energy. 2015;75:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2014.09.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salcedo-Sanz S, Del Ser J, Landa-Torres I, Gil-Lpez S, Portilla-Figueras JA (2014) The coral reefs optimization algorithm: a novel metaheuristic for efficiently solving optimization problems. Sci World J. Article ID 739768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Salcedo-Sanz S, Pastor-Snchez A, Gallo-Marazuela D, Portilla-Figueras A (2013) A novel coral reefs optimization algorithm for multi-objective problems. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 8206. pp 326–333

- Sarkara S, Dasb S, Chaudhuric SS. A multilevel color image thresholding scheme based on minimum cross entropy and differential evolution. Pattern Recognit Lett. 2015;54:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.patrec.2014.11.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Storn R, Price K. Differential evolutionła simple and efficient heuristic for global optimization over continuous spaces. J Glob Optim. 1997;11:341–359. doi: 10.1023/A:1008202821328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Lv Q, Wang B, Zhang L. Airport detection in remote sensing images: a method based on saliency map. Cogn Neurodyn. 2013;7(2):143–154. doi: 10.1007/s11571-012-9223-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wennekers T, Palm G. Syntactic sequencing in Hebbian cell assemblies. Cogn Neurodyn. 2009;3(4):429–441. doi: 10.1007/s11571-009-9095-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh IC. Modeling of strength of high performance concrete using artificial neural networks. Cem Concr Res. 1988;28:1797–1808. doi: 10.1016/S0008-8846(98)00165-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu QY, Qin AK, Suganthan PN, Huang GB. Evolutionary extreme learning machine. Pattern Recognit. 2005;38:1759–1763. doi: 10.1016/j.patcog.2005.03.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]