The crystal structure of racemic tetrahydroberberine, a pharmacologically active alkaloid, shows intermolecular 1,3-benzodioxole –CH2⋯OCH3 and –OCH3⋯OCH3 interactions.

Keywords: tetrahydroberberine, canadine, berberine derivative, alkaloid, crystal structure, biological activity, C—H⋯O hydrogen bonding, quinolizidine core

Abstract

Tetrahydroberberine (systematic name: 9,10-dimethoxy-5,8,13,13a-tetrahydro-6H-benzo[g][1,3]benzodioxolo[5,6-a]quinolizine), C20H21NO4, a widely distributed naturally occurring alkaloid, has been crystallized as a racemic mixture about an inversion center. A bent conformation of the molecule is observed, with an angle of 24.72 (5)° between the arene rings at the two ends of the reduced quinolizinium core. The intermolecular hydrogen bonds that play an apparent role in crystal packing are 1,3-benzodioxole –CH2⋯OCH3 and –OCH3⋯OCH3 interactions between neighboring molecules.

Introduction

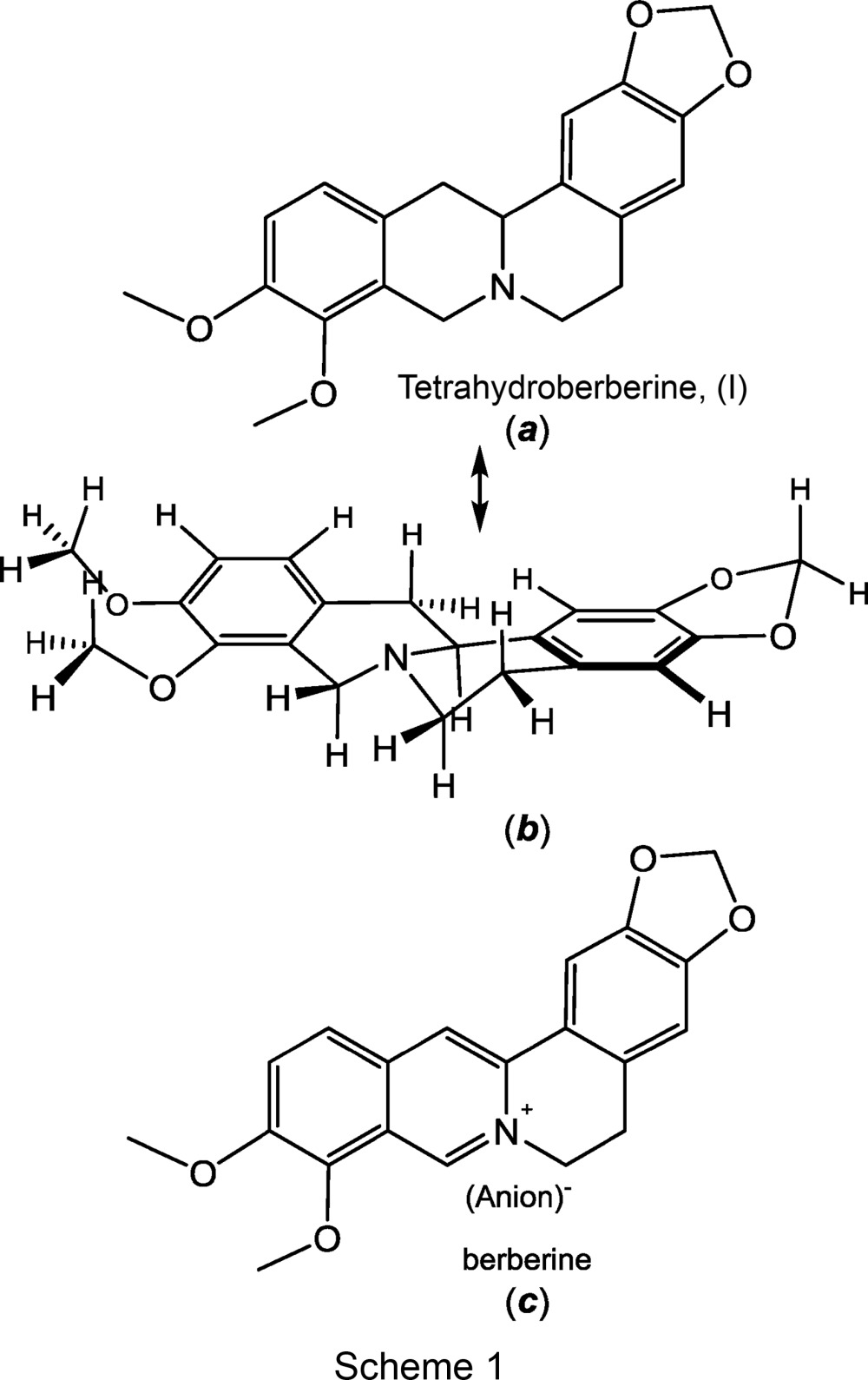

Tetrahydroberberine, also known as canadine and xanthopuccine, is a naturally occurring alkaloid that occurs in widely distributed shrubs, both deciduous and evergreen, of the genus Berberis. Berberine (see Scheme 1), the fully oxidized form of the compound, has long been known to exert a broad variety of potentially useful pharmacological and therapeutic properties, ranging from antimalarial (Ho, 2013 ▸; Bansal & Silakari, 2014 ▸) to anticancer agents (Kaboli et al., 2014 ▸; Anwarul Bashar et al., 2014 ▸; Ortiz et al., 2014 ▸). The understanding of these properties and their application to human medicine continue to be active areas of research. Only more recently has recognition emerged that the fully reduced form of berberine, i.e. tetrahydroberberine, has significant pharmacological activity that differs from the parent berberine. For example, in contrast to the cytotoxic effects of berberine, tetrahydroberberine has been reported to show little cytotoxicity toward several lines of cells, but instead to be effective as an antioxidant (Correché et al., 2008 ▸). Consequently, it holds promise as an anti-inflammatory agent. Other studies have reported biological effects of tetrahydroberberine and its derivatives as a Ca2+ channel blocker (Kubota et al., 1994 ▸; Li et al., 1995 ▸, 2002 ▸; Dai et al., 1996 ▸), which enables the induction of vascular muscle relaxation and its use as antihypertension and anti-arrhythmia agents. Tetrahydroberberine has also been observed to block ATP-sensitive K+ ion channels that are associated with the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease (Wu et al., 2010 ▸), indicating an important neuroprotective role. Still other research has found an inhibitory effect upon platelet aggregation, suggesting an important role in protecting against thrombosis (Bo et al., 1994 ▸).

In earlier work (Pingali et al., 2014 ▸), we described the structure of dihydroberberine in the crystalline state and noted that it shows a capacity to engage in CH2⋯X (X = O, N) hydrogen bonding that could have pertinence to the nature of interactions with in vivo systems. As noted in that report, dihydroberberine and derivatives of it show manifold pharmacological effects that may have use in the treatment of human disease. In a continuing effort to more fully characterize small organic molecules that exert important therapeutic properties, we report the crystal structure of (±)-tetrahydroberberine, which has heretofore not been described. Earlier works by others have reported the structures of protonated (Sakai et al., 1987 ▸) and N-methylated (Kamigauchi et al., 2003 ▸) forms of tetrahydroberberine and of tetrahydroberberine in a 2:1 complex with (+)-2,3-di-p-toluyltartaric acid (Gao et al., 2008 ▸).

Experimental

Synthesis and crystallization

To a stirred refluxing solution of berberine chloride (3.71 g, 10 mmol) and K2CO3 (3.6 g, 26 mmol) in MeOH (125 ml), solid NaBH4 (0.4 g, 10 mmol) was added portionwise. The reaction mixture was allowed to reflux for an additional 20 min, during which time it became a homogeneous solution. Stirring was continued for an additional 4 h at ambient temperature, and the precipitated product was then collected by filtration and recrystallized from absolute EtOH (400 ml) to afford 2.6 g (77%) of material as pale-yellow–brown needles (m.p. 447–449 K).

Spectroscopic data

MS (m/z) 339; 1H NMR (DMSO-d 6): δ 6.90 (s, 1H), 6.87 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.84 (s, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.65 (s, 1H), 5.93 (d, 2H, J = 2.4 Hz), 4.04 (d, 1H, J = 16.0 Hz), 3.76 (s, 3H), 3.71 (s, 3H), 3.35 (d, 1H, J = 16.0 Hz), 3.27–3.36 (m, 2H), 3.08 (q, 1H, J = 3.6 Hz), 2.85–2.93 (m, 1H), 2.61 (m, 1H), 2.55 (q, 1H, J = 4.0 Hz), 2.43 (q, 1H, J = 3.2 Hz).

Refinement

Crystal data, data collection and structure refinement details are summarized in Table 1 ▸. H atoms were identified in the later difference maps, and their positions were refined, as were their isotropic displacement parameters. The latter were approximately 1.2–1.5 times those of the C atoms to which they were attached.

Table 1. Experimental details.

| Crystal data | |

| Chemical formula | C20H21NO4 |

| M r | 339.38 |

| Crystal system, space group | Monoclinic, P21/n |

| Temperature (K) | 150 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 10.516 (3), 14.796 (5), 10.620 (3) |

| β (°) | 101.986 (4) |

| V (Å3) | 1616.3 (9) |

| Z | 4 |

| Radiation type | Mo Kα |

| μ (mm−1) | 0.10 |

| Crystal size (mm) | 0.39 × 0.17 × 0.03 |

| Data collection | |

| Diffractometer | Bruker SMART APEX CCD diffractometer |

| Absorption correction | Multi-scan (SADABS; Sheldrick, 2009 ▸) |

| T min, T max | 0.650, 0.997 |

| No. of measured, independent and observed [I > 2σ(I)] reflections | 23937, 3306, 2468 |

| R int | 0.069 |

| (sin θ/λ)max (Å−1) | 0.625 |

| Refinement | |

| R[F 2 > 2σ(F 2)], wR(F 2), S | 0.050, 0.132, 1.09 |

| No. of reflections | 3306 |

| No. of parameters | 310 |

| H-atom treatment | All H-atom parameters refined |

| Δρmax, Δρmin (e Å−3) | 0.25, −0.28 |

Results and discussion

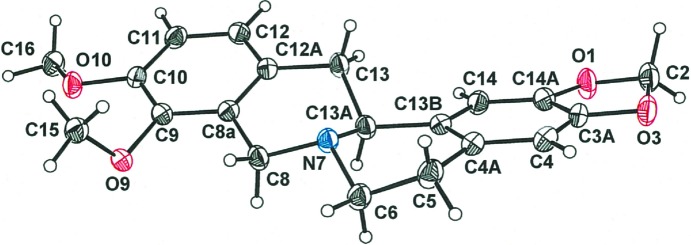

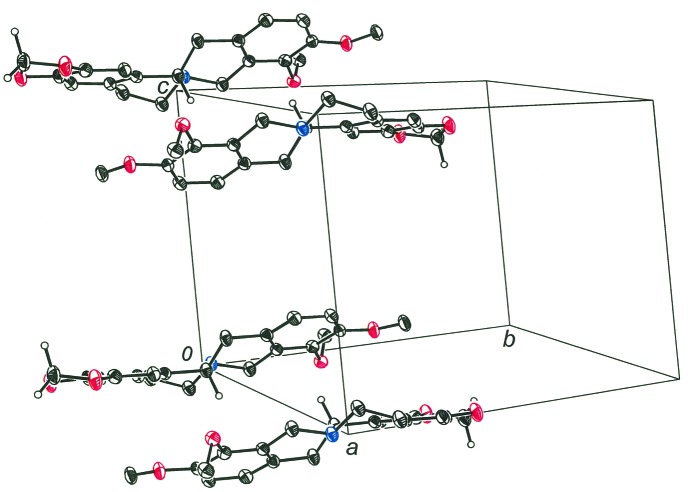

The structure of tetrahydroberberine, (I), is presented in part (a) of Scheme 1 and rendered three dimensionally in part (b) such that its nonplanarity is emphasized. The compound may be described as a saturated quinolizine system fused at the 1,2-positions to a 1,3-benzodioxole system and to a dimethoxybenzene fragment at the 7,8-positions. The saturation of bonds within the central quinolizine system induces pseudo-chair-type conformations to its two rings and necessitates chirality at the tertiary N atom and at atom C13A. The H atom bound to C13A has an anti disposition relative to the electron lone pair of N7 [see part (b) of Scheme 1, and Fig. 1 ▸]. In the displacement ellipsoid plot shown in Fig. 1 ▸, atoms N7 and C13A display R and S configurations, respectively. Because of the centrosymmetry of the space group, the S (N7) and R (C13A) enantiomer must occur in the cell as well. Pairs of enantiomers are arranged about the inversion centers at the mid-points of the a edges of the cell (Fig. 2 ▸). The dihedral angle between the C6 arene groups at the two ends of the molecule is 24.72 (5)°, which is the simplest way to quantify its departure from planarity. The corresponding value in dihydroberberine was observed to be modestly larger at 27.94 (5)° (Pingali et al., 2014 ▸).

Figure 1.

Displacement ellipsoid plot drawn at the 50% probability level, showing the complete atom labeling for tetrahydroberberine.

Figure 2.

Pairs of tetrahydroberberine enantiomers arranged about the inversion centers at the mid-points of the a edges of the unit cell.

A dihedral angle of 31.5 (1)° between the mean planes of the C6 arene rings at the ends of the tetrahydroberberine molecule in the 2:1 tetrahydroberberine (+)-2,3-di-p-toluyltartaric acid complex has been reported (Gao et al., 2008 ▸). For a rigid molecule such as tetrahydroberberine, this appreciably larger value is greater than would be plausibly attributed to packing effects or to statistical variance. Our independent assessment of the structure reported by Gao and co-workers finds values of 25 (1) and 22 (1)° for the the two independent molecules in the unit cell. Rather than being a single optical isomer as reported, the two tetrahydroberberine molecules appear to be enantiomers, and the occurrence of noncentric P1 as space group appears to be due to the presence of the optically pure (+)-2,3-di-p-toluyltartaric acid cocrystallite.

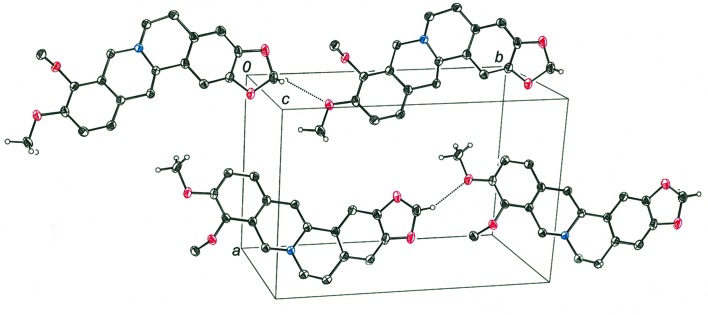

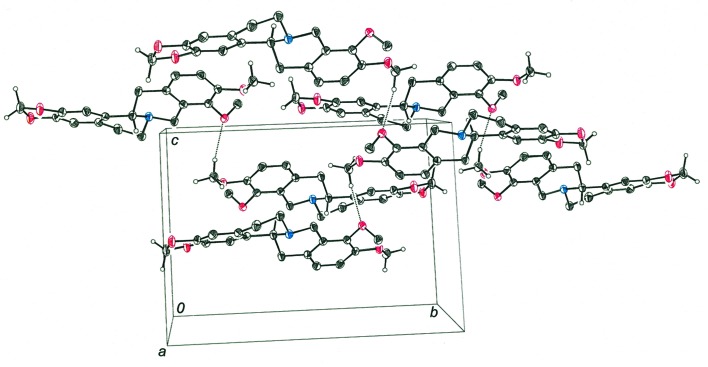

As was found in the crystal structure of dihydroberberine, weak intermolecular hydrogen bonding appears to play a role in governing the packing of molecules in the crystalline state of tetrahydroberberine. A notable difference between the packing arrangements of the two molecules is that tetrahydroberberine molecules are disposed relative to one another in such a way that their tertiary N atoms are unable to engage potential hydrogen-bond donors. Whereas the acetal-type –CH2– group of 1,3-benzodioxole of dihydroberberine participates in both CH2⋯N and CH2⋯OMe hydrogen bonds with neighboring molecules, only the latter type of hydrogen bond is found in the arrangement of molecules for tetrahydroberberine. As seen in Fig. 3 ▸, molecules of tetrahydroberberine related by translation along the b axis of the unit cell present the –CH2– group of the 1,3-benzodioxole fragment near the methoxy O atom of the next molecule such that it can serve as a hydrogen-bond acceptor (Table 2 ▸). Weak hydrogen bonding may also be operative between a methoxy H atom of one molecule and the methoxy O atom of an adjoining molecule further along in the direction of the c axis of the unit cell (Fig. 4 ▸ and Table 2 ▸). These intermolecular hydrogen bonds are undoubtedly weaker than those involving the acetal-type –CH2– hydrogens, as the latter are more activated by the proximity of two electronegative O atoms rather than one.

Figure 3.

Tetrahydroberberine molecules related by translation along the b axis of the unit cell. Dashed lines show the intermolecular C—H⋯OCH3 hydrogen bonds.

Table 2. Hydrogen-bond geometry (Å, °).

| D—H⋯A | D—H | H⋯A | D⋯A | D—H⋯A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C2—H2B⋯O10i | 0.94 (2) | 2.58 (2) | 3.212 (3) | 124.5 (17) |

| C16—H16A⋯O9ii | 0.95 (2) | 2.53 (2) | 3.455 (3) | 162.9 (18) |

Symmetry codes: (i)  ; (ii)

; (ii)  .

.

Figure 4.

Cell packing diagram for tetrahydroberberine, with intermolecular OCH3⋯OCH3 hydrogen bonds shown as dashed lines.

Much remains to be learned about the physical and chemical underpinnings of the pharmacological activity of tetrahydroberberine. The capacity for tetrahydroberberine to act as both hydrogen-bond donor and acceptor suggest that this property be considered as a key basis for some of its selective activity in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Crystal structure: contains datablock(s) I, global. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229615004076/ky3073sup1.cif

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) I. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229615004076/ky3073Isup2.hkl

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229615004076/ky3073Isup3.cml

CCDC reference: 1051389

Acknowledgments

This work is funded in part by the Louisiana Cancer Research Consortium (LCRC) and the National Center for Research Resources RCMI Program Grant 2 G12MD007595–06 (to FPS). The Louisiana Board of Regents is thanked for enhancement grant LEQSF-(2002-03)-ENH-TR-67, with which the Tulane X-ray diffractometer was purchased, and Tulane University is acknowledged for its ongoing support with operational costs for the diffraction facility. Support from the National Science Foundation (grant No. CHE-0845829 to JPD) is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Anwarul Bashar, A. B. M., Hossan, Md. S., Jahan, R., Al-Nahain, A., Mahmudul Haque, A. K. M. & Rahmatullah, M. (2014). World J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 3, 1858–1869.

- Bansal, Y. & Silakari, O. (2014). Eur. J. Med. Chem. 76, 31–42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bo, X., Wei, W. & De-Xin, L. (1994). Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 15, 133–135.

- Bruker (2008). SHELXTL. Bruker AXS Inc., Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

- Bruker (2009). SAINT. Bruker AXS Inc., Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

- Bruker (2010). APEX2. Bruker AXS Inc., Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

- Correché, E. R., Andujar, S. A., Kurdelas, R. R., Gómez-Lechón, M. J., Freile, M. L. & Enriz, R. D. (2008). Bioorg. Med. Chem. 16, 3641–1651. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dai, D.-Z., Yu, F., Li, H.-T., Tang, Y.-Q., An, L.-F., Huang, W.-L., Peng, S.-X., Hao, X.-M., Zhou, B.-A. & Hu, C.-H. (1996). Drug Develop. Res. 39, 138–146.

- Gao, J.-M., Liu, W.-T., Li, M.-L., Liu, H.-W., Zhang, X.-C. & Li, Z.-X. (2008). J. Mol. Struct. 892, 466–469.

- Ho, J. W. S. (2013). Anti-Infect. Agents, 11, 70–74.

- Kaboli, P. J., Rahmat, A., Ismail, P. & Ling, K.-H. (2014). Eur. J. Pharmacol. 740, 584–595. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kamigauchi, M., Yoshida, M., Noda, Y., Nishijo, J., In, Y., Tomoo, K., Ohishi, H. & Ishida, T. (2003). Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn, 76, 587–593.

- Kubota, K., Morota, T., Yano, S. & Watanabe, K. (1994). Jpn Kokai Tokkyo Koho JP 06072876 A 19940315.

- Li, C., Guo, J. & Liu, T. (2002). Zhonghua Yixue Zazhi, 82, 57–60.

- Li, X. T., Wang, W. L., Wang, J. X. & Yang, S. J. (1995). Yaoxue Xuebao, 30, 567–572.

- Ortiz, L. M. G., Lombardi, P., Tillhon, M. & Scovassi, A. I. (2014). Molecules, 19, 12349–12367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pingali, S., Donahue, J. P. & Payton-Stewart, F. (2014). Acta Cryst. C70, 388–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sakai, T., Taira, Z., Kamigauchi, M. & Takao, N. (1987). Acta Cryst. C43, 98–101.

- Sheldrick, G. M. (2008). Acta Cryst. A64, 112–122. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G. M. (2009). SADABS. University of Göttingen, Germany.

- Sheldrick, G. M. (2015). Acta Cryst. C71, 3–8.

- Wu, C., Yang, K., Liu, Q., Wakui, M., Jin, G.-Z., Zhen, X. & Wu, J. (2010). Neuropharmacology, 59, 567–572. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Crystal structure: contains datablock(s) I, global. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229615004076/ky3073sup1.cif

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) I. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229615004076/ky3073Isup2.hkl

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229615004076/ky3073Isup3.cml

CCDC reference: 1051389