Abstract

Viral infections are important contributors to exacerbation of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; however, the role of viruses in the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is less clear. This likely reflects that fact that IPF acute exacerbations are defined clinically as “noninfectious,” and little attention has been paid to the outcomes of patients with IPF with diagnosed infections. However, accumulating evidence suggests that infections (both bacterial and viral) may influence disease outcomes either as exacerbating agents or initiators of disease. Support for a viral role in disease initiation comes from studies demonstrating the presence of herpesviral DNA and epithelial cell stress in the lungs of asymptomatic relatives at risk for developing familial IPF. In addition, the number of studies that can associate viral (especially herpesviral) signatures in the lung with the development of IPF is steadily growing, and activated leukocyte signatures in patients with IPF provide further support for infectious processes driving IPF progression. Animal modeling has been used to better understand how a gamma herpesvirus infection can modulate the pathogenesis of lung fibrosis and has demonstrated that preceding infections appear to reprogram lung epithelial cells during latency to produce profibrotic factors, making the lung more susceptible to subsequent fibrotic insult, whereas exacerbations of existing fibrosis, or infections in susceptible hosts, involve active viral replication and are influenced by antiviral therapy. In addition, there is new evidence that bacterial burden in the lungs of patients with IPF may predict a poor prognosis.

Keywords: herpesvirus, lung, aging, fibroblast, immunity

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a rare interstitial lung disease characterized by progressive accumulation of extracellular matrix, worsening dyspnea, and impaired gas exchange. The disease incidence and prevalence increases with each decade of life, with the mean age at diagnosis being approximately 65 years. The mean survival from this disease is between 3 and 5 years after diagnosis (1–3). The natural history of the disease can vary, with some patients experiencing periods of relative stability, some patients showing steady decline in lung function, and some patients experiencing periods of acute worsening (4–6). Given the pathologic features of IPF, which include temporal and spatial heterogeneity in areas of lung damage and fibrosis, epithelial cell injury, diffuse alveolar damage, and variable inflammation (7), it has been suggested that viruses may represent etiologic agents of disease (8). In fact, there is a growing body of literature that may suggest there are reasons to suspect a viral etiology in this disease. Such suggestions are based on the following: (1) IPF is associated with aging, and aging is associated with immunosenescence, particularly in the face of chronic viral infections (9); (2) two small studies have suggested that patients with IPF treated with antiviral medications (valacyclovir and gancyclovir) showed improvement (10, 11); (3) the spatial and temporal heterogeneity of lung pathology in IPF are reminiscent of an infectious etiology (7); (4) the recent PANTHER-IPF (Prednisone, Azathioprine, and N-Acetylcysteine: A Study That Evaluates Response in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis) trial concluded that immunosuppression can be harmful in patients with IPF, suggesting that immune cell function is needed to limit disease pathogenesis (12); and (5) growing evidence suggests that patients with IPF are characterized by activated leukocyte populations and increased expression of host defense genes (13–17). Given this rationale, a number of studies have examined viruses as potential agents of IPF pathogenesis, and these studies are briefly reviewed below.

Human Studies

Hepatitis C Virus

Given the known ability of hepatitis C virus (HCV) to induce liver cirrhosis, this virus has received attention in studies of lung fibrosis as well. Two studies have suggested a positive association between HCV and IPF. Ueda and colleagues demonstrated that HCV antibodies were found in 28% of patients in an IPF cohort versus only 3.6% of a control cohort population (18). Additionally, Arase and colleagues demonstrated that the incidence of IPF was higher at 10 (0.3%) and 20 (0.9%) years after HCV infection than it was in a cohort of patients infected with hepatitis B virus (19). However, HCV is more prevalent in many forms of lung disease, and thus it may not be specific to IPF (20). Finally, one study found no association between HCV infection and IPF (21).

Adenovirus

Given that adenovirus is a persistent virus and that the adenoviral E1A protein has the ability to induce profibrotic transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) secretion from epithelial cells and to induce epithelial–mesenchymal transition (22), it was suggested that adenovirus infection may promote IPF development. However, two clinical studies have found no support for this hypothesis. Kumano and colleagues could not identify E1A DNA at higher levels in IPF than in control cases (23), and Yonemaru and colleagues found no elevation of antiadenoviral IgG in the sera of patients with IPF (24).

Torque-Teno (Transfusion-Transmitted) Virus

The Torque-Teno (Transfusion-Transmitted) (TT) virus, a single-stranded DNA virus originally identified in a patient with post-transfusion hepatitis, has also been studied in patients with IPF. Among the patients with IPF tested, 36.4% were positive for TTV DNA. A higher percentage of patients with IPF who were positive for TTV died within 4 years (6/12 patients; 50%) when compared with patients with IPF who were TTV negative (6/21; 28.6%) (25). The same study also noted that patients with IPF who develop lung cancer had higher TTV titers than did patients who did not develop cancer (25). However, this virus has also been seen in patients with lung cancer and acute lung injury; thus, the specificity of TTV in driving IPF pathogenesis is still unclear (25, 26). Recently it was shown that TTV was the most frequently identified virus in a group of patients with IPF diagnosed with acute exacerbation (26). These data have certainly raised the question of whether an infectious agent, even if occult, could drive the pathogenesis of some cases of IPF acute exacerbation.

Herpesviruses

Herpesviruses comprise a large family of ubiquitous DNA viruses that include many common pathogens. This family of viruses by far has received the greatest attention as either an etiologic or exacerbating agent of IPF. The fact that these viruses can establish life-long latency in the host with the potential to reactivate makes them attractive candidates for a viral infection that could “reemerge” to cause disease in older individuals. However, the fact that these viruses are common pathogens when IPF is a rare disease suggests that, if true, there must be genetic or environmental factors that are not yet understood. One suggestion has been that patients predisposed to harbor herpesviruses in the lung (as opposed to other body tissues) may be at increased risk. As discussed below, 18 studies have shown an association of herpesvirus with IPF, acute exacerbation of IPF, or patients at risk for familial IPF in lung samples, and four studies have shown an association with serologic studies. However, three studies have been negative (27–29), raising questions about the potential for geographic differences, disease heterogeneity, or sensitivity.

In the studies that have examined serology, Vegnon and colleagues found anti–Epstein Barr virus (EBV) IgG in 5 of 13 patients with IPF (30), Yonemaru and colleagues found evidence of anti-EBV, anti–herpes simplex virus (HSV-1), and anti-cytomegalovirus (CMV) antibodies in patients with IPF. Strikingly, anti-CMV IgG was found in 80% of patients with IPF versus 30% of control subjects (24). Magro and colleagues found anti-CMV IgG in 9 of 19 patients with IPF tested (31), and Manika and colleagues found anti-EBV IgA in 60% of patients with IPF versus 22% of control patients (32).

Regarding studies within the lung, there are numerous examples suggesting that herpesvirus DNA or proteins are increased in patients with IPF. Such studies have shown EBV DNA to be present in 3 of 17 bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples from patients with IPF (32); 11 of 12 patients with IPF tested positive for EBV, whereas 3 of 12 tested positive for human herpesvirus 6 (33). Lasithiotaki and colleagues found evidence for HSV-1 in 1 of 11 patients with IPF tested but in none of six control subjects (34). Forty percent (22/55) of patients with IPF had evidence of EBV DNA in the lungs versus only 7.3% of control subjects (3/41). Interestingly, in this study, the presence of EBV DNA correlated with increased arterial thickening and mean arterial pressure, suggesting that the viral infection may influence the development of pulmonary hypertension in these patients (35).

Other studies examining IPF lungs for evidence of herpesviral infection have shown CMV RNA to be present despite the fact that the typical cytoplasmic inclusion bodies were not evident (31). Stewart and colleagues noted that 41% of patients with IPF (11/27) but no control patients were positive for EBV by immunohistochemistry and PCR (36). In other studies, Tsukamoto and colleagues found that 96% of IPF lungs were positive for EBV DNA versus 71% of controls. When looking at biopsy specimens in this same study, 9 of 29 patients with IPF had evidence of the viral latent membrane protein (LMP) in their epithelial cells, whereas none of the control patients did. When analyzing the disease course of the patients with IPF who demonstrated LMP positivity, four of the nine LMP-positive patients died rapidly, compared with only one rapid death in the 20 LMP-negative patients (37). Kelly and colleagues reported that 61% of IPF biopsies showed evidence of the productive EBV Whzet DNA rearrangement, suggesting the occurrence of lytic infection (38). Assuming that any herpesvirus might be able to have a similar influence on IPF pathogenesis, Tang and colleagues noted that 97% of patients with IPF had evidence of one or more of CMV, EBV, HHV7, or HHV8 infection(s), whereas only 36% of control patients had such findings (10). One of the most intriguing studies to date comes from Folcik and colleagues, who looked for evidence of Herpesvirus saimiri DNA in patients with IPF. They found evidence consistent with the presence of H. saimiri DNA in the regenerating epithelium of 21 of 21 IPF biopsies examined, whereas none was found the control lung epithelial cells (39). This herpesvirus is actually a pathogen of squirrel monkeys but has been shown to infect up to 7% of humans. Although the transmission of this virus to patients with IPF is unclear, the limited infection rate of this virus in humans is more consistent with an etiologic agent of a rare disease such as sporadic IPF. Another reason that this report is interesting is that the animal modeling that has been done for herpesvirus influences on lung fibrosis have used murine gamma herpesvirus-68 (γHV-68), and this murine virus has a high homology to H. saimiri.

Several studies have explored herpesvirus in patients with both sporadic and familial forms of IPF. Patients with sporadic IPF often had evidence of two or more herpesviruses in the lung, whereas patients with familial IPF often had only one herpesvirus present. In the patients with familial IPF, this was most often CMV and rarely was KSHV (10). In another important study, patients with both familial and sporadic forms of IPF were tested for evidence of EBV, CMV, or Kaposi’s sarcoma herpes virus (KSHV or HHV8) in lung epithelial cells. Fifteen of 23 patients with IPF with sporadic or familial forms of disease had evidence of herpesvirus infection, whereas none of the 10 control patients did. Interestingly, in patients with herpesvirus DNA, there was also evidence of endoplasmic reticulum stress, as evidenced by markers of the unfolded protein response in the same cells (40). This is one of the first studies to suggest a mechanism for epithelial damage that could potentiate viral-mediated pathogenesis. In this regard, a single case report also noted evidence of EBV DNA in IPF epithelial cells (41). More recently, an elegant study from Kropski and colleagues examined asymptomatic relatives of patients with familial IPF. Eleven of 75 at-risk subjects (14%) had evidence of interstitial changes by high-resolution CT scan, whereas 35.2% had abnormalities on transbronchial biopsies. Interestingly, at-risk subjects had increased herpesvirus DNA in cell-free BAL and evidence of herpesvirus antigen expression in alveolar epithelial cells, which correlated with expression of endoplasmic reticulum stress markers (42). These data may be the best evidence to date that patients at risk for IPF may experience herpesviral infections of lung epithelium even before disease symptoms are evident.

Acute Exacerbations

Acute exacerbations of IPF are defined clinically as noninfectious, yet several studies have suggested that occult infections may play some role. The studies discussed above by Wootton and colleagues found infection in 19 of 43 cases of acute IPF exacerbation. These included 12 cases of TTV, one case of parainfluenza, two cases of rhinovirus, one case of coronavirus, one case of HSV-1, and two cases of EBV (26). Ushiki and colleagues examined 14 cases of IPF acute exacerbation and found evidence of respiratory syncytial virus in one case and CMV in two cases (43). In a study in Brazil, 10% of IPF acute exacerbation cases demonstrated evidence of measles or CMV infection (44). Taken together, the accumulating data suggest that acute exacerbations may result from multiple causes. In some cases, there is evidence of an infection, and it is likely that immune stimulation in response to that infection may drive acute worsening of the disease. This would be consistent with the observations that viral infections cause exacerbation of other lung diseases, such as asthma and COPD (reviewed in References 45–47). However, many instances of IPF acute exacerbation are not associated with infections, and thus there must also be a pathogenic mechanism that is disease intrinsic. Another important difference between acute exacerbations of IPF and other lung diseases is that the mortality of acute exacerbation in IPF is very high (5, 48), whereas this is not the case in asthma or COPD exacerbations.

Animal Models

Preceding Infection

One of the most striking demonstrations that a herpesvirus can cause fibrosis in a natural host comes from the work of Williams and colleagues, who demonstrated that experimental infection of horses with an equine gamma herpesvirus could cause fibrosis (49). In murine models, we have shown that an infection with γHV-68 given 14 to 70 days before a fibrotic insult can augment the subsequent development of lung fibrosis even if the fibrotic insults (bleomycin or fluorescein isothiocyanate) are not sufficient to induce fibrosis on their own (50), in agreement with a previous study (51). In this setting, it appears that the virus can be latent and that lytic replication is not critical for the ability of the virus to augment the subsequent fibrotic response (50). When trying to identify mechanisms for how the latent viral infection might affect fibrogenesis, we found that latent viral infection in the lung was associated with increased production of chemokines that can recruit fibrocytes and other inflammatory cells. We also noted enhanced release of cysteinyl leukotrienes, tumor necrosis factor α, and TGF-β in latently infected lungs or lung cells (50, 52).

Aging

Because IPF is a disease of aged individuals, it is possible that aged lungs are more susceptible to viral infection than young lungs. To determine this experimentally, two groups instilled γHV-68 into the lungs of aged mice (>15 mo) and found that old, but not young, mice developed viral-induced fibrosis (53, 54). Mechanisms associated with the induction of fibrosis in old, but not young, animals included enhanced production of TGF-β from infected mesenchymal cells and increased responsiveness to TGF-β, leading to enhanced expression of extracellular matrix genes (53). In addition, aged epithelial cells infected with the virus undergo endoplasmic reticulum stress, which may also promote fibrogenesis (54).

Bone Marrow Transplant

Although not related to IPF, other conditions that can be associated with fibrosis in the lung occur after stem cell transplantation (e.g., idiopathic pneumonia syndrome, nonspecific interstitial fibrosis, or bronchiolitis obliterans). Like acute exacerbations of IPF, these are believed to be noninfectious in nature (55). However, animal modeling suggests that γHV-68 infection may also influence lung fibrosis after stem cell transplant (56). Similar to the situation noted for preceding infection in fibrosis models above, in the stem cell transplant model viral replication can be blocked using cidofovir starting on Day 5 with no impact on the subsequent development of lung fibrosis on Day 21 after infection (unpublished observation). In this model it appears the effector T cell responses are skewed to Th17 rather than Th1 (57), and our unpublished observations highlight a role for IL-17 in mediating the fibrotic response to this virus.

Exacerbation of Existing Fibrosis

In contrast to the models discussed above where latent virus is able to promote fibrogenesis, studies that look at the impact of viral infection on already established fibrosis uncover differences in pathogenic mechanisms. Giving the virus after challenge with fluorescein isothiocyanate (58) or bleomycin (59) exacerbates the deposition of collagen in the lung. Interestingly, in this model there may be some specificity for γHV-68 infection because influenza and murine CMV do not have the same effect (59). The ability to exacerbate established fibrosis was dependent on the ability of the virus to undergo lytic replication and reactivation, and this was correlated with TGF-β signaling and epithelial cell apoptosis (59).

Th2-Biased Mice

Another model that has been used to demonstrate that herpesviruses can promote fibrosis is the infection of Th2-biased mice lacking IFN-γ or the IFN-γ receptor (60–63). The requirement for lytic replication and reactivation is also a feature of fibrosis that develops after infection in these Th2-biased mice (63). In these mice, development of alternatively activated macrophages plays an important role in pathogenesis (64, 65), but it has also been noted that therapeutic administration of antiviral therapies can have some beneficial effect. Administration of cidofovir to block viral replication starting on Day 45 after infection (a time point when the mice were asymptomatic) reduced the percentage of mice with severe fibrosis from 40 to 10% by 180 days after infection. Additionally, giving the cidofovir starting at Day 60 after infection, when mice were already symptomatic, improved survival from 20 to 80%, even though fibrosis persisted in 60% of the mice (63). These studies offer some hope that antiviral therapies may help limit reactivation to improve mortality.

Conclusions

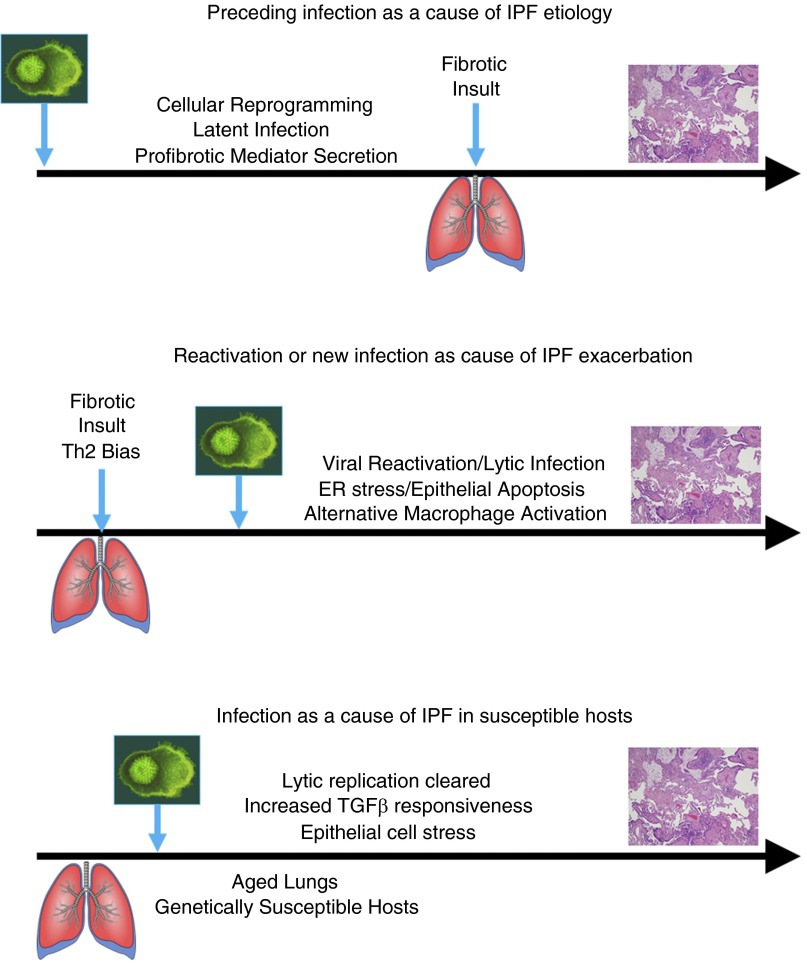

The clinical data that are accumulating and discussed above suggest that viral infections may play some role in the etiology of IPF. It is tempting to speculate that reactivation of viral infection in older individuals may predispose to fibrotic progression. Alternatively, reprogramming of lung epithelial or mesenchymal cells by latent infection may drive fibrotic processes over time. Observations that latently infected cells can produce profibrotic mediators suggest that a preceding infection may help to promote a more exuberant response to a subsequent fibrotic stimulus. In these cases, it appears that the mechanisms responsible for fibrotic etiology may not require lytic replication or cellular destruction but instead may represent cellular reprogramming. In contrast, the ability of viruses to exacerbate existing fibrosis may involve different mechanisms. In animal models, exacerbation requires lytic replication (summarized in Figure 1). Models of fibrosis that are dependent on lytic replication may be mediated by epithelial cell stress and accumulation of alternatively activated macrophages. Although there is evidence that occult viral infections can be identified in some cases of IPF acute exacerbation, most cases do not show such infections. One possible explanation for this is that the acute exacerbation occurs as a consequence of an earlier viral infection that is no longer present at the time of disease symptoms. Our stem cell transplant studies suggest this scenario is possible. However, our animal models of viral exacerbation suggest that latent virus is ineffective in worsening extracellular matrix deposition; if we extrapolate this finding to humans, it would suggest that acute exacerbations should show evidence of lytic viral replication, but this is certainly not universally seen.

Figure 1.

Potential mechanisms for viral influence on the etiology or exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) based on pathogenic mechanisms uncovered in animal models. (Top) Preceding infection may help initiate IPF pathogenesis by reprogramming of lung cells during latent infection. (Middle) Exacerbation of existing fibrosis likely involves lytic replication. (Bottom) Aged lungs or genetically susceptible hosts may be able to clear the lytic infection, but, due to alterations in the lung environment (e.g., increased sensitivity to transforming growth factor β [TGF-β]), the outcome of infection leads to fibrosis. ER = endoplasmic reticulum.

Future Directions

Armed with data from human and animal studies regarding viral influences on fibrosis, what should pulmonologists focus on for the future?

Trial of Antiviral Medication

We are intrigued by the small studies showing benefit for antiherpes treatment in some patients with IPF (10, 11). This suggests that there may be value in a larger study to evaluate antiviral therapy. One would predict that the benefit would be highest in patients with documented evidence of recent viral infection or reactivation, and this should be considered as an entry criteria for such a study. Of course, the challenge here is determining what tissue to sample to diagnose a herpesvirus infection in the IPF population. Using serologic assays on blood will be complicated by the fact that herpesvirus infections are common in the general population. Based on the literature described above, the most accurate determination is likely to come from examination of lung tissue. This presents a problem because the number of biopsies being performed to diagnose IPF is dropping as the diagnostic accuracy of high-resolution CT improves. However, many patients with IPF can safely undergo BAL. Given the sensitivity of PCR techniques, it is hoped that analysis of BAL could be used for inclusion criteria in such a trial. In fact, this suggestion is supported by the work of Kropski and colleagues, who demonstrated the ability to detect herpesvirus DNA in cell-free BAL in asymptomatic relatives of patients with familial IPF (42).

Studies of Infectious Exacerbation of IPF

One thing that became very clear at the recent Transatlantic Conference on Lung Disease was that IPF is one of the few pulmonary diseases that define exacerbations as noninfectious. This is not to say that patients with IPF do not develop lung infections but that outcomes of such infections are not well documented in the literature. We believe that a concerted effort should be made to understand what happens to patients with IPF who do develop bacterial or viral pneumonias. Clinically it is appreciated that these patients do poorly when they develop pneumonia, but how the infection affects their disease process is unknown. For example, we do not yet know whether patients with IPF who develop pneumonia and increased dyspnea do so due to enhanced extracellular matrix deposition or simply due to fluid accumulation. We suggest that researchers should make it a priority to collect biological specimens and clinical data in this patient population to begin to address these questions.

Biological Basis for Viral Pathogenesis

One finding that is still somewhat surprising to us is that not all viruses are capable of exacerbating established fibrosis in murine models (59). Given that this pathogenesis relates to viral replication, it is unclear why some lytic viruses can exacerbate (γHV-68), whereas others do not (influenza, CMV). The biological basis for this difference should be a focus of future investigation because this may lead to a greater understanding of how viral infections modulate lung cell functions.

Differences in Outcomes of Viral Infection in Different Lung Diseases

Why is it that viral infections are common causes of exacerbations of asthma and COPD but not necessarily in IPF? What is it about the biology of the IPF lung versus the COPD or asthmatic lung that makes the outcomes of viral infection different? The mortality of certain infections is likely different between these patient populations, and this may be an arena for future discovery.

Bacterial Infections as Mediators of IPF Outcome

Although this review has focused on viral infections in the exacerbation and etiology of IPF, it is also likely that bacterial infections may play a role in disease progression in some patients. Recent microbiome analyses of IPF BAL specimens determined that increased relative abundance of two operational taxonomic units (Streptococcus OTU1345 and Staphylococcus OTU1348) were positively associated with IPF disease progression (66). In another study, bacterial burden in the BAL of patients with IPF was found to be greater than in control subjects, and the baseline bacterial burden predicted the rate of decline in lung function and the risk of death (67). This study identified Haemophilus, Streptococcus, Neisseria, and Veillonella species to be more abundant in patients with IPF than in control subjects. Interestingly, in animal modeling, infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa did not exacerbate bleomycin-induced fibrosis (59), raising the possibility that there may be some bacterial specificity for these responses or that the bleomycin model cannot accurately predict how bacterial infection will alter disease course in humans. Taken together, the human data suggest that both viral and bacterial pathogens may predict poor outcomes for patients with IPF.

Nonviral Acute Exacerbations of IPF

Although we believe that viruses are important contributors to both the etiology and exacerbation of IPF, it is also clear that some cases of acute worsening are likely to be noninfectious. What drives the emergence of diffuse alveolar damage and enhanced extracellular matrix deposition in the cases that are noninfectious? Is this related to aging or some other environmental trigger? What causes the intrinsic process of IPF progression to accelerate? This is a very important area for future investigation as well.

Footnotes

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL115618 and AI117229.

This article is a summary of a presentation made at the 2015 Transatlantic Conference on Lung Disease focused on Mechanisms of Exacerbation of Lung Disease and is intended as an Annals of ATS Supplement.

Author Contributions: B.B.M. and T.A.M. researched the literature, drafted the review, edited the manuscript, and approved of the final version. B.B.M. takes accountability for all aspects of the work related to accuracy and integrity of the publication.

The views expressed in this article do not communicate an official position of the University of Michigan or the National Institutes of Health.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Fell CD, Martinez FJ, Liu LX, Murray S, Han MK, Kazerooni EA, Gross BH, Myers J, Travis WD, Colby TV, et al. Clinical predictors of a diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:832–837. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200906-0959OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raghu G, Weycker D, Edelsberg J, Bradford WZ, Oster G. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:810–816. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200602-163OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collard HR. The age of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:771–772. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0049ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xaubet A, Ancochea J, Bollo E, Fernández-Fabrellas E, Franquet T, Molina-Molina M, Montero MA, Serrano-Mollar A Sociedad Española de Neumología y Cirugía Torácica (SEPAR) Research Group on Diffuse Pulmonary Diseases. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Arch Bronconeumol. 2013;49:343–353. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collard HR, Moore BB, Flaherty KR, Brown KK, Kaner RJ, King TE, Jr, Lasky JA, Loyd JE, Noth I, Olman MA, et al. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Clinical Research Network Investigators. Acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:636–643. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-463PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinez FJ, Safrin S, Weycker D, Starko KM, Bradford WZ, King TE, Jr, Flaherty KR, Schwartz DA, Noble PW, Raghu G, et al. IPF Study Group. The clinical course of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:963–967. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-12_part_1-200506210-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khalil N, O'Connor R. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: current understanding of the pathogenesis and the status of treatment. CMAJ. 2004;171:153–160. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1030055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vannella KM, Moore BB. Viruses as co-factors for the initiation or exacerbation of lung fibrosis. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2008;1:2. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fülöp T, Larbi A, Pawelec G. Human T cell aging and the impact of persistent viral infections. Front Immunol. 2013;4:271. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang YW, Johnson JE, Browning PJ, Cruz-Gervis RA, Davis A, Graham BS, Brigham KL, Oates JA, Jr, Loyd JE, Stecenko AA. Herpesvirus DNA is consistently detected in lungs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:2633–2640. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2633-2640.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egan JJ, Adamali HI, Lok SS, Stewart JP, Woodcock AA. Ganciclovir antiviral therapy in advanced idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an open pilot study. Pulm Med. 2011;2011:240805. doi: 10.1155/2011/240805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raghu G, Anstrom KJ, King TE, Jr, Lasky JA, Martinez FJ Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Clinical Research Network. Prednisone, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine for pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1968–1977. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang IV, Luna LG, Cotter J, Talbert J, Leach SM, Kidd R, Turner J, Kummer N, Kervitsky D, Brown KK, et al. The peripheral blood transcriptome identifies the presence and extent of disease in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37708. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herazo-Maya JD, Noth I, Duncan SR, Kim S, Ma SF, Tseng GC, Feingold E, Juan-Guardela BM, Richards TJ, Lussier Y, et al. Peripheral blood mononuclear cell gene expression profiles predict poor outcome in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:205ra136. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feghali-Bostwick CA, Tsai CG, Valentine VG, Kantrow S, Stoner MW, Pilewski JM, Gadgil A, George MP, Gibson KF, Choi AM, et al. Cellular and humoral autoreactivity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Immunol. 2007;179:2592–2599. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilani SR, Vuga LJ, Lindell KO, Gibson KF, Xue J, Kaminski N, Valentine VG, Lindsay EK, George MP, Steele C, et al. CD28 down-regulation on circulating CD4 T-cells is associated with poor prognoses of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e8959. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore BB, Fry C, Zhou Y, Murray S, Han MK, Martinez FJ, Flaherty KR The COMET Investigators. Inflammatory leukocyte phenotypes correlate with disease progression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Front Med. 2014;1(56) doi: 10.3389/fmed.2014.00056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ueda T, Ohta K, Suzuki N, Yamaguchi M, Hirai K, Horiuchi T, Watanabe J, Miyamoto T, Ito K. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and high prevalence of serum antibodies to hepatitis C virus. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146:266–268. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.1.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arase Y, Suzuki F, Suzuki Y, Akuta N, Kobayashi M, Kawamura Y, Yatsuji H, Sezaki H, Hosaka T, Hirakawa M, et al. Hepatitis C virus enhances incidence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:5880–5886. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.5880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meliconi R, Andreone P, Fasano L, Galli S, Pacilli A, Miniero R, Fabbri M, Solforosi L, Bernardi M. Incidence of hepatitis C virus infection in Italian patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thorax. 1996;51:315–317. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.3.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Irving WL, Day S, Johnston ID. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and hepatitis C virus infection. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:1683–1684. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.6_Pt_1.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayashi S, Hogg JC. Adenovirus infections and lung disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2007;7:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuwano K, Nomoto Y, Kunitake R, Hagimoto N, Matsuba T, Nakanishi Y, Hara N. Detection of adenovirus E1A DNA in pulmonary fibrosis using nested polymerase chain reaction. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:1445–1449. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10071445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yonemaru M, Kasuga I, Kusumoto H, Kunisawa A, Kiyokawa H, Kuwabara S, Ichinose Y, Toyama K. Elevation of antibodies to cytomegalovirus and other herpes viruses in pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:2040–2045. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10092040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bando M, Ohno S, Oshikawa K, Takahashi M, Okamoto H, Sugiyama Y. Infection of TT virus in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Med. 2001;95:935–942. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2001.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wootton SC, Kim DS, Kondoh Y, Chen E, Lee JS, Song JW, Huh JW, Taniguchi H, Chiu C, Boushey H, et al. Viral infection in acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1698–1702. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201010-1752OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wangoo A, Shaw RJ, Diss TC, Farrell PJ, du Bois RM, Nicholson AG. Cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis: lack of association with Epstein-Barr virus infection. Thorax. 1997;52:888–891. doi: 10.1136/thx.52.10.888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dworniczak S, Ziora D, Kapral M, Mazurek U, Niepsuj G, Rauer R, Wilczok T, Kozielski J. Human cytomegalovirus DNA level in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2004;55:67–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zamò A, Poletti V, Reghellin D, Montagna L, Pedron S, Piccoli P, Chilosi M. HHV-8 and EBV are not commonly found in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2005;22:123–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vergnon JM, Vincent M, de Thé G, Mornex JF, Weynants P, Brune J. Cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis and Epstein-Barr virus: an association? Lancet. 1984;2:768–771. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)90702-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Magro CM, Allen J, Pope-Harman A, Waldman WJ, Moh P, Rothrauff S, Ross P., Jr The role of microvascular injury in the evolution of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;119:556–567. doi: 10.1309/0B06-Y93E-GE6T-Q36Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manika K, Alexiou-Daniel S, Papakosta D, Papa A, Kontakiotis T, Patakas D, Antoniadis A. Epstein-Barr virus DNA in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2007;24:134–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pulkkinen V, Salmenkivi K, Kinnula VL, Sutinen E, Halme M, Hodgson U, Lehto J, Jääskeläinen A, Piiparinen H, Kere J, et al. A novel screening method detects herpesviral DNA in the idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis lung. Ann Med. 2012;44:178–186. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2010.532151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lasithiotaki I, Antoniou KM, Vlahava VM, Karagiannis K, Spandidos DA, Siafakas NM, Sourvinos G. Detection of herpes simplex virus type-1 in patients with fibrotic lung diseases. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e27800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calabrese F, Kipar A, Lunardi F, Balestro E, Perissinotto E, Rossi E, Nannini N, Marulli G, Stewart JP, Rea F. Herpes virus infection is associated with vascular remodeling and pulmonary hypertension in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e55715. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stewart JP, Egan JJ, Ross AJ, Kelly BG, Lok SS, Hasleton PS, Woodcock AA. The detection of Epstein-Barr virus DNA in lung tissue from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1336–1341. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.4.9807077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsukamoto K, Hayakawa H, Sato A, Chida K, Nakamura H, Miura K. Involvement of Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 in disease progression in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thorax. 2000;55:958–961. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.11.958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kelly BG, Lok SS, Hasleton PS, Egan JJ, Stewart JP. A rearranged form of Epstein-Barr virus DNA is associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:510–513. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2103058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Folcik VA, Garofalo M, Coleman J, Donegan JJ, Rabbani E, Suster S, Nuovo A, Magro CM, Di Leva G, Nuovo GJ. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is strongly associated with productive infection by herpesvirus saimiri. Modern Pathol. 2014;27:851–862. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lawson WE, Crossno PF, Polosukhin VV, Roldan J, Cheng DS, Lane KB, Blackwell TR, Xu C, Markin C, Ware LB, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in alveolar epithelial cells is prominent in IPF: association with altered surfactant protein processing and herpesvirus infection. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294:L1119–L1126. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00382.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marzouk K, Corate L, Saleh S, Sharma OP. Epstein-Barr-virus-induced interstitial lung disease. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2005;11:456–460. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000176678.38539.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kropski JA, Pritchett JM, Zoz DF, Crossno PF, Markin C, Garnett ET, Degryse AL, Mitchell DB, Polosukhin VV, Rickman OB, et al. Extensive phenotyping of individuals at risk for familial interstitial pneumonia reveals clues to the pathogenesis of interstitial lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:417–426. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201406-1162OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ushiki A, Yamazaki Y, Hama M, Yasuo M, Hanaoka M, Kubo K. Viral infections in patients with an acute exacerbation of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Respir Investig. 2014;52:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santos GC, Parra ER, Stegun FW, Cirqueira CS, Capelozzi VL. Immunohistochemical detection of virus through its nuclear cytopathic effect in idiopathic interstitial pneumonia other than acute exacerbation. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2013;46:985–992. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20132885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu X, Chen D, Gu X, Su X, Song Y, Shi Y. Prevalence and risk of viral infection in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a meta-analysis. Mol Biol Rep. 2014;41:4743–4751. doi: 10.1007/s11033-014-3345-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hershenson MB. Rhinovirus-induced exacerbations of asthma and COPD. Scientifica. 2013;2013:405876. doi: 10.1155/2013/405876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kurai D, Saraya T, Ishii H, Takizawa H. Virus-induced exacerbations in asthma and COPD. Front Microbiol. 2013;4:293. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim DS, Collard HR, King TE., Jr Classification and natural history of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:285–292. doi: 10.1513/pats.200601-005TK. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams KJ, Robinson NE, Lim A, Brandenberger C, Maes R, Behan A, Bolin SR. Experimental induction of pulmonary fibrosis in horses with the gammaherpesvirus equine herpesvirus 5. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e77754. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vannella KM, Luckhardt TR, Wilke CA, van Dyk LF, Toews GB, Moore BB. Latent herpesvirus infection augments experimental pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:465–477. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200905-0798OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lok SS, Haider Y, Howell D, Stewart JP, Hasleton PS, Egan JJ. Murine gammaherpes virus as a cofactor in the development of pulmonary fibrosis in bleomycin resistant mice. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:1228–1232. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00272902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stoolman JS, Vannella KM, Coomes SM, Wilke CA, Sisson TH, Toews GB, Moore BB. Latent infection by γherpesvirus stimulates profibrotic mediator release from multiple cell types. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;300:L274–L285. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00028.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Naik PN, Horowitz JC, Moore TA, Wilke CA, Toews GB, Moore BB. Pulmonary fibrosis induced by γ-herpesvirus in aged mice is associated with increased fibroblast responsiveness to transforming growth factor-β. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67:714–725. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Torres-González E, Bueno M, Tanaka A, Krug LT, Cheng DS, Polosukhin VV, Sorescu D, Lawson WE, Blackwell TS, Rojas M, et al. Role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in age-related susceptibility to lung fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;46:748–756. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0224OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Uhlving HH, Andersen CB, Christensen IJ, Gormsen M, Pedersen KD, Buchvald F, Heilmann C, Nielsen KG, Mortensen J, Moser C, et al. Biopsy-verified bronchiolitis obliterans and other noninfectious lung pathologies after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21:531–538. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coomes SM, Farmen S, Wilke CA, Laouar Y, Moore BB. Severe gammaherpesvirus-induced pneumonitis and fibrosis in syngeneic bone marrow transplant mice is related to effects of transforming growth factor-β. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:2382–2396. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Coomes SM, Wilke CA, Moore TA, Moore BB. Induction of TGF-beta 1, not regulatory T cells, impairs antiviral immunity in the lung following bone marrow transplant. J Immunol. 2010;184:5130–5140. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McMillan TR, Moore BB, Weinberg JB, Vannella KM, Fields WB, Christensen PJ, van Dyk LF, Toews GB. Exacerbation of established pulmonary fibrosis in a murine model by gammaherpesvirus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:771–780. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200708-1184OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ashley SL, Jegal Y, Moore TA, van Dyk LF, Laouar Y, Moore BB. γ-Herpes virus-68, but not Pseudomonas aeruginosa or influenza A (H1N1), exacerbates established murine lung fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2014;307:L219–L230. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00300.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dutia BM, Clarke CJ, Allen DJ, Nash AA. Pathological changes in the spleens of gamma interferon receptor-deficient mice infected with murine gammaherpesvirus: a role for CD8 T cells. J Virol. 1997;71:4278–4283. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4278-4283.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ebrahimi B, Dutia BM, Brownstein DG, Nash AA. Murine gammaherpesvirus-68 infection causes multi-organ fibrosis and alters leukocyte trafficking in interferon-gamma receptor knockout mice. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:2117–2125. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64683-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bartholdy C, Høgh-Petersen M, Storm P, Holst PJ, Orskov C, Christensen JP, Thomsen AR. IFNγ and perforin cooperate to control infection and prevent fatal pathology during persistent gammaherpesvirus infection in mice. Scand J Immunol. 2014;79:395–403. doi: 10.1111/sji.12176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mora AL, Torres-González E, Rojas M, Xu J, Ritzenthaler J, Speck SH, Roman J, Brigham K, Stecenko A. Control of virus reactivation arrests pulmonary herpesvirus-induced fibrosis in IFN-gamma receptor-deficient mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:1139–1150. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200610-1426OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gangadharan B, Hoeve MA, Allen JE, Ebrahimi B, Rhind SM, Dutia BM, Nash AA. Murine gammaherpesvirus-induced fibrosis is associated with the development of alternatively activated macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:50–58. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0507270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mora AL, Torres-González E, Rojas M, Corredor C, Ritzenthaler J, Xu J, Roman J, Brigham K, Stecenko A. Activation of alveolar macrophages via the alternative pathway in herpesvirus-induced lung fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;35:466–473. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0121OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Han MK, Zhou Y, Murray S, Tayob N, Noth I, Lama VN, Moore BB, White ES, Flaherty KR, Huffnagle GB, et al. COMET Investigators. Lung microbiome and disease progression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an analysis of the COMET study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:548–556. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70069-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Molyneaux PL, Cox MJ, Willis-Owen SA, Mallia P, Russell KE, Russell AM, Murphy E, Johnston SL, Schwartz DA, Wells AU, et al. The role of bacteria in the pathogenesis and progression of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:906–913. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201403-0541OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]