A GH30 subfamily 8 (GH30-8) xylanase with functional properties different from the canonical GH30-8 glucuronoxylan xylanohydrolases has been biochemically and structurally characterized. The findings highlight the diversity of xylanolytic activities that derive from the GH30 family of glycoside hydrolases.

Keywords: wildfire, low-value biomass, xylanase, glycoside hydrolase family 30

Abstract

Endoxylanases classified into glycoside hydrolase family 30 subfamily 8 (GH30-8) are known to hydrolyze the hemicellulosic polysaccharide glucuronoxylan (GX) but not arabinoxylan or neutral xylooligosaccharides. This is owing to the specificity of these enzymes for the α-1,2-linked glucuronate (GA) appendage of GX. Limit hydrolysis of this substrate produces a series of aldouronates each containing a single GA substituted on the xylose penultimate to the reducing terminus. In this work, the structural and biochemical characterization of xylanase 30A from Clostridium papyrosolvens (CpXyn30A) is presented. This xylanase possesses a high degree of amino-acid identity to the canonical GH30-8 enzymes, but lacks the hallmark β8–α8 loop region which in part defines the function of this GH30 subfamily and its role in GA recognition. CpXyn30A is shown to have a similarly low activity on all xylan substrates, while hydrolysis of xylohexaose revealed a competing transglycosylation reaction. These findings are directly compared with the model GH30-8 enzyme from Bacillus subtilis, XynC. Despite its high sequence identity to the GH30-8 enzymes, CpXyn30A does not have any apparent specificity for the GA appendage. These findings confirm that the typically conserved β8–α8 loop region of these enzymes influences xylan substrate specificity but not necessarily β-1,4-xylanase function.

1. Introduction

Each year, in the United States alone, billions of dollars are spent on the control of wildfires to protect lives and property. Systematic clearing of low-value forest biomass serves to control catastrophic wildfires, but is cost-prohibitive. Our research focuses on enzyme applications which may increase the worth of such ‘low-value biomass’ through the development of new technologies.

Proteins classified into glycoside hydrolase (GH) family 30 (GH30) of the Carbohydrate Active Enzymes (CAZy) database (Cantarel et al., 2009 ▸) have recently been categorized into subfamilies (St John et al., 2010 ▸). Biochemical and structural studies have shown the enzymes in subfamily 8 to have unique characteristics in the degradation of the hemicellulosic polymer glucuronoxylan (St John et al., 2006 ▸; Vršanská et al., 2007 ▸; Hurlbert & Preston, 2001 ▸). These endoxylanases only cleave the β-1,4-linked xylan chain near positions substituted with α-1,2-linked glucuronic acid (GA), resulting in a newly generated reducing terminus having a GA on the penultimate xylose.

An explanation for this unique mode of action has been derived from two ligand-bound crystal structures representing diverse subfamily member enzymes (St John et al., 2011 ▸; Urbániková et al., 2011 ▸). These structures show that GH30-8 xylanases tightly coordinate the α-1,2-linked GA substituted on the xylose in this position. While both the β7–α7 and β8–α8 loop regions of these enzymes provide stabilizing contacts, specificity is primarily endowed through a salt bridge that is established between the C-6 carboxylate of the GA and an arginine which extends out from the β8–α8 loop. For these endoxylanases the rate of hydrolysis of neutral xylooligosaccharides has been shown to be about three orders of magnitude lower than the polymeric GA-containing substrate (Urbániková et al., 2011 ▸).

The closely related GH30-7 subfamily has also been assigned a xylanase function. Enzymes most similar to the GH30-7 subfamily of xylanases have now been shown to have two diverse xylanolytic activities. These include a reducing terminus-specific exoxylanase activity (Tenkanen et al., 2013 ▸) and an activity identical to the GH30-8 GA targeting endoxylanases which, in part, is the focus of this work (Biely et al., 2014 ▸). Even though GH30 subfamilies 7 and 8 are closely related, their levels of amino-acid identity are in the low 20% range and, as might be expected, the β8–α8 loop region is not conserved. These findings suggest that small differences in the three-dimensional structure of enzymes within the same subfamily may result in distinct functional properties.

In light of the apparent role of the β8–α8 loop region in imparting substrate specificity to the GH30-8 subfamily, amino-acid sequence studies were implemented to identify homologs possessing sequence differences in this region. A putative xylanase derived from the lignocellulose-degrading bacterium Clostridium papyrosolvens (CpXyn30A) was identified and chosen for study. In this report, we present the three-dimensional structure of this unique GH30 subfamily 8 homolog determined using X-ray crystallographic methods and provide functional characterization of the enzyme in comparison to the canonical GH30 subfamily 8 xylanase XynC from Bacillus subtilis (BsXynC). The results highlight the role of the typically conserved β8–α8 loop in providing xylanase hydrolysis specificity but not general xylanase function.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. DNA synthesis and protein expression

The sequence for UniProt ID C7IMC9 (deleted 05/2012 and replaced by ID F1TBY8) was identified for this study and the expression-optimized coding sequence (Welch et al., 2009 ▸) including an amino-terminal hexahistidine tag was ordered from DNA 2.0 (Menlo Park, California, USA) in the kanamycin-resistant pJexpress 441 expression vector. Plasmid DNA was used to transform Escherichia coli Rosetta 2 (DE3) cells for expression. The cells were grown with shaking at 250 rev min−1 and 37°C in Luria–Bertani broth with 30 µg ml−1 kanamycin until they reached an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6. The cells were induced by the addition of isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside to 0.5 mM and grown as above for 5 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 7500 rev min−1 for 20 min at 4°C. The resulting pellet was suspended in 50 mM sodium phosphate, 100 mM NaCl pH 7.2 at a ratio of 5 ml per gram of cell pellet. A 1 µl aliquot of 1000× Halt protease inhibitor (Thermo Fisher, Rockford, Illinois, USA) was added for every 1 ml of buffer used. Suspended cells were lysed by sonication and the lysate was centrifuged at 11 000 rev min−1 for 30 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatant was dialyzed overnight at 4°C against 50 mM sodium phosphate, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole pH 7.2 using 10 000 Da molecular-weight cutoff dialysis tubing.

2.2. Purification

The post-dialysis material was centrifuged and the supernatant was clarified by passage through a 0.22 µm filter. The solution was then loaded onto a 1 ml HisTrap Fast Flow column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA) charged with Ni2+ and the hexahistidine-tagged recombinant protein was eluted with a linear gradient of 0–500 mM imidazole in 50 mM sodium phosphate, 250 mM NaCl pH 7.2. SDS–PAGE-verified (Laemmli, 1970 ▸) peak fractions were combined and dialyzed against 50 mM sodium phosphate, 250 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole pH 7.2 overnight at 4°C as above. A second purification step using a 1 ml HisTrap column charged with Co2+ was then employed with the same elution scheme as above. A single large peak was obtained from this run and peak fractions were analyzed by SDS–PAGE to ascertain purity and size. Peak fractions were combined and dialyzed into 20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl pH 7.2. In a separate preparation meant solely for biochemical studies, CpXyn30A was purified as described but the final purified protein was dialyzed against 30 mM Tris–HCl, 50 mM NaCl pH 7.5. After dialysis, the protein solution was concentrated to at least 5 mg ml−1 and stored at −80°C until crystallization or functional studies. The GH30-8 xylanase from B. subtilis 168, XynC, was purified as previously described (St John et al., 2006 ▸, 2011 ▸). Protein concentration was routinely determined from the absorbance at 280 nm using the extinction coefficient predicted by ProtParam (Gasteiger et al., 2005 ▸).

2.3. Crystallization

The sparse-matrix screens Crystal Screen, Crystal Screen 2, Index and PEG/Ion as well as the Sodium Malonate and Ammonium Sulfate Grid Screens (Hampton Research, Aliso Viejo, California, USA) were used for initial screening. Sitting-drop vapor-diffusion experiments were performed in 24-well microplates (Art Robbins Instruments, Sunnyvale, California, USA). Each well contained 300 µl precipitant solution and drops were set up using 1 µl protein solution and 1 µl precipitant. The plates were sealed with sealing film and were incubated at 25°C. A crystallization condition consisting of 0.1 M ammonium acetate, 0.1 M bis-tris pH 5.5, 17% polyethylene glycol 10 000 was found using the Index screen. Sitting-drop vapor-diffusion experiments were performed using this condition at protein concentrations of 6.5 and 10 mg ml−1, and cubic crystals (∼0.5 mm on edge) were obtained in the drops containing CpXyn30A at a concentration of 6.5 mg ml−1. Crystals were harvested for cryocrystallographic data collection by transferring them stepwise to solutions containing 5, 10 and 20%(v/v) glycerol in well solution. After the transfer into 20% glycerol, the crystals were flash-cooled and stored in liquid nitrogen until data collection.

2.4. Data collection, analysis and model building

Data were collected on a Rigaku RU-H3R copper rotating-anode generator operating at 50 kV and 100 mA fitted with Confocal Max-Flux optics (Osmic Inc., Troy, Michigan, USA) and a Rigaku R-AXIS IV+ image-plate detector. A 180° data set was collected with 5 min exposure times and a φ oscillation of 0.5° per image. The resulting data were processed to 2.01 Å and the crystal belonged to the orthorhombic space group C2221, with unit-cell parameters a = 66.0, b = 76.5, c = 150.6 Å, α = β = γ = 90.00°. Data were indexed and integrated in iMosflm (Battye et al., 2011 ▸), scaled in SCALA (Evans, 2006 ▸) and initial molecular-replacement phases (using PDB entries 3gtn and 1nof as models; St John et al., 2009 ▸; Larson et al., 2003 ▸), electron-density map calculation and model building were performed with Phaser (McCoy et al., 2007 ▸), PHENIX (Adams et al., 2010 ▸) and Coot (Emsley et al., 2010 ▸), respectively. The final model (PDB entry 4fmv) was studied and figures were prepared using PyMOL (DeLano, 2002 ▸).

2.5. Biochemicals and assays

All reagents were of the highest purity available. The xylooligosaccharides xylobiose (X2) and xylotriose (X3) were purchased from Wako Chemicals (Richmond, Virginia, USA) and xylotetraose (X4), xylopentaose (X5) and xylohexaose (X6) were purchased from Megazyme International (Wicklow, Ireland). Concentrations of xylooligosaccharide standards were determined with the phenol–sulfuric acid total carbohydrate assay (DuBois et al., 1956 ▸). The aldouronate aldopenturonate (GX4), with a GA residue substituted penultimate to the nonreducing terminus of X4, was the aldouronate limit product of a GH11 xylanase (Biely et al., 1997 ▸; Trichoderma longibrachiatum XynII, Hampton Research, Aliso Viejo, California, USA) and was purified using a 1.7 m P-2 resin column (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, USA) in 50 mM formic acid. The Rotovap-concentrated sugar was then loaded onto the same column equilibrated with water to remove the formic acid from the oligosaccharide. The desalted GX4 was lyophilized, dissolved in water and the concentration was determined by the Blumenkrantz assay for total uronic acid content (Blumenkrantz & Asboe-Hansen, 1973 ▸).

2.6. Enzymatic activity measurements and hydrolysis product studies

Activity measurements on polymeric substrates were determined through reducing-end quantification with Nelson’s test (Nelson, 1944 ▸) as previously described (St John et al., 2006 ▸). Conditions for hydrolysis by CpXyn30A were optimized using beech-wood xylan (Sigma–Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri, USA) in acetate buffers ranging in pH from 3 to 6. Thermostability was analyzed using enzyme pre-incubations at a range of temperatures from 4 to 50°C followed by activity assessment at 30°C. Activity measurements for functional comparison were performed using sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua) wood glucuronoxylan (SGX; kindly provided by James F. Preston from the University of Florida) and wheat arabinoxylan (WAX; Megazyme International). Hydrolysis of xylooligosaccharides was analyzed using an Agilent 1260 HPLC (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California, USA) with resolution of neutral xylooligosaccharides performed using a Phenomenex RNO column (Phenomenex. Torrance, California, USA) with water as eluent at a flow rate of 0.3 ml min−1 and 75°C. The refractive index of the eluate was monitored throughout the separations. Hydrolysis reactions were performed in 25 µl volumes under optimized conditions (100 mM sodium acetate pH 4.5 at 30°C) with xylooligosaccharides at 12.1 mM, a concentration (of X6) that approximated that of the polysaccharide used in the reactions employing polymeric xylan substrates. Reactions were stopped by boiling the samples in a water bath for 5 min. All HPLC analyses were performed in triplicate using 5 µl injections. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed as described previously (St John et al., 2006 ▸; Bounias, 1980 ▸).

2.7. Amino-acid sequence studies

Sequences were aligned with MAFFT (Katoh & Toh, 2008 ▸) and the alignment figure was generated with ESPript (Gouet et al., 2003 ▸) using the server available at http://espript.ibcp.fr. Domain prediction was performed using the online CD-search program (Marchler-Bauer et al., 2011 ▸) available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi and the domain representation was created using DOG 1.0 (Ren et al., 2009 ▸). Phylogenetic relationships were calculated and represented using MEGA 6.0 (Tamura et al., 2013 ▸).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Selection of CpXyn30A

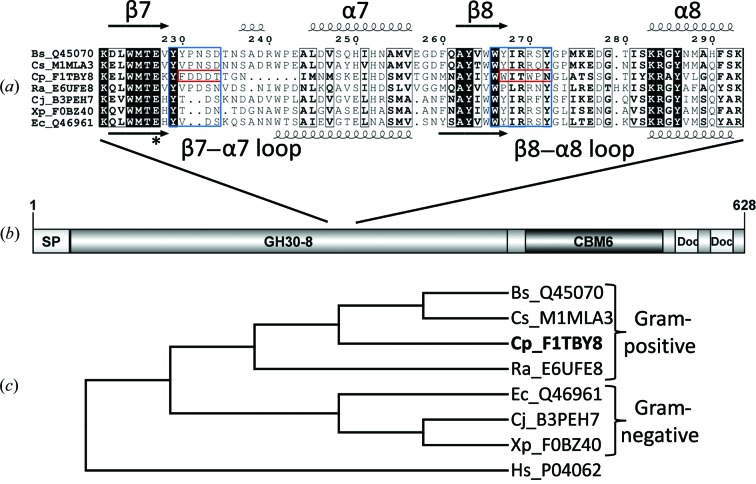

Primary amino-acid sequence alignments (Fig. 1 ▸ a) identified a GH30-8 enzyme that did not contain the normally conserved β8–α8 loop sequence. For this enzyme (UniProt ID F1TBY8), sequence studies verified the existence of the two conserved glutamate amino-acid side chains which catalyze the double-displacement reaction common to CAZy Clan A enzymes (Henrissat, 1998 ▸) and identified a likely secretion signal sequence in addition to noncatalytic modules positioned C-terminal to the GH30-8 catalytic module. These include a family 6 carbohydrate-binding module (CBM6) for binding soluble glucan and two dockerin domains presumably for interaction within a cellulosome assembly (Fig. 1 ▸ b). Combined, these features suggest that this enzyme may have a role in the degradation of the xylan component of lignocellulosic biomass. Phylogenetic analysis of CpXyn30A verifies the most similar enzymes to be GH30-8 homologs from Gram-positive organisms (Fig. 1 ▸ c). The 54.5% amino-acid identity between CpXyn30A and BsXynC is indicative of a very strong likelihood of identical function. Based on these findings and an interest in the characterization of a GH30-8 enzyme with a nonconserved amino-acid sequence in the β8–α8 loop, the coding sequence for the gene was ordered from DNA 2.0 with the SignalP (Petersen et al., 2011 ▸) predicted secretion signal sequence replaced by an amino-terminal methionine and with a hexahistidine tag appended to the new carboxy-terminus defined by the end of a GH30-8 sequence alignment effectively truncating the protein sequence before the predicted (Bateman et al., 2004 ▸) CBM6 and dockerin domains.

Figure 1.

Sequence analysis of CpXyn30A. (a) An alignment with conserved secondary-structure elements of the β7–α7 and β8–α8 loop regions representing the area of GA coordination in the characterized GH30-8 enzymes (BsXynC, Bs_Q45070; EcXynA, Ec_Q46961). The specific regions which contain the amino acids which directly coordinate the GA are boxed in blue and the same regions from CpXyn30A are in red. (b) The domain architecture of CpXyn30A showing the GH30 catalytic module followed by a family 6 CBM and two dockerin domains presumably for inclusion in a cellulosome complex. (c) Phylogram depicting the distribution of CpXyn30A relative to homologous GH30-8 Gram-positive and Gram-negative derived enzymes rooted to a GH30-1 enzyme. Sequences are identified through their unique UniProt accession number preceded by the initials of the bacterium. Other sequences used in this comparison included Cs_M1MAL3 from C. saccharoperbutylacetonicum, Ra_E6UFE8 from Ruminococcus albus, Cj_B3PEH7 from Cellvibrio japonicus, Xp_F0BZ40 from Xanthomonas perforans and the GH30-1 subfamily enzyme Hs_P04062 from Homo sapiens used as an outgroup for the phylogenetic analysis.

3.2. Structure of CpXyn30A

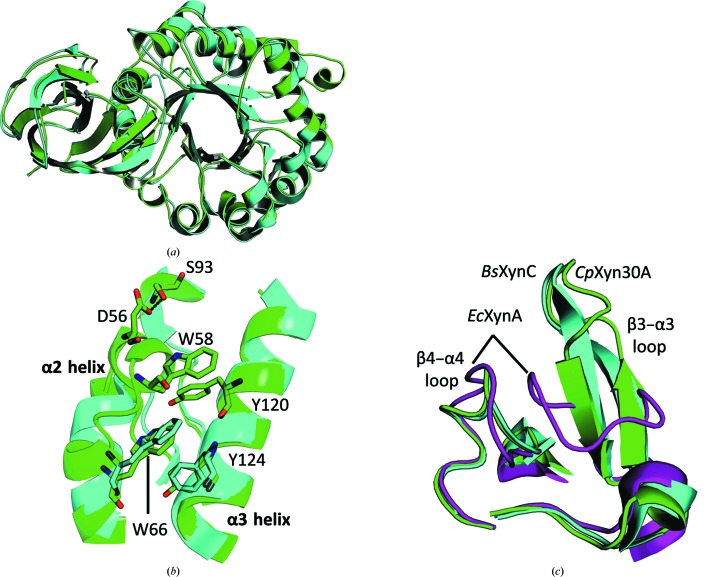

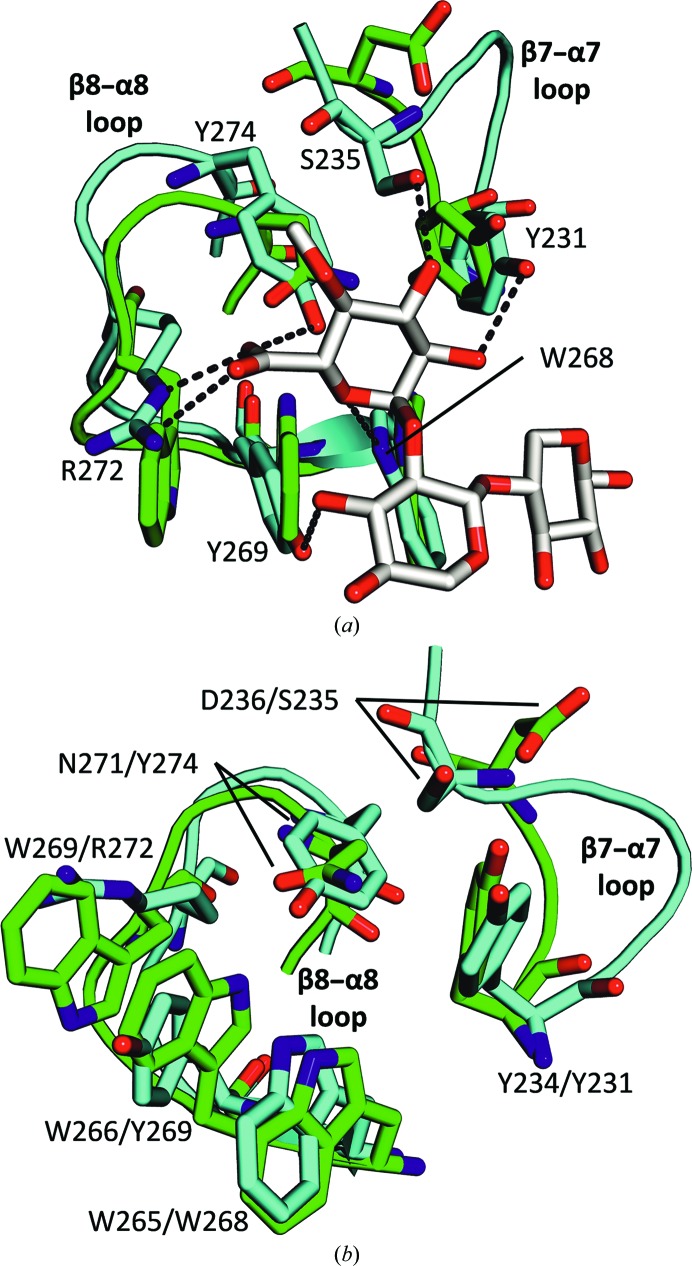

Refinement and model-quality statistics for the CpXyn30A structure model are presented in Table 1 ▸. As expected, the overall structure of CpXyn30A is very similar to those of other GH30-8 enzymes. An all-atom r.m.s.d. of 0.95 Å is obtained for superposition with XynC, a GH30 xylanase from B. subtilis (BsXynC) (Fig. 2 ▸ a). However, the structure of CpXyn30A in the (β/α)8 catalytic core domain is notably different from BsXynC (PDB entry 3kl5; St John et al., 2011 ▸) in the β1–α1, β2–α2 (Figs. 2 ▸ b and 2 ▸ c) and β7–α7 loops and also in the CpXyn30A unique β8–α8 loop region (Figs. 3 ▸ a and 3 ▸ b), which was the primary consideration for this study.

Table 1. Data-collection and refinement statistics for C. papyrosolvens Xyn30A.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| PDB code | 4fmv |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.542 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 38.30–2.01 (2.08–2.01) |

| Space group | C2221 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å) | a = 66.0, b = 76.5, c = 150.6 |

| Total reflections | 46801 (4031) |

| Unique reflections | 24506 (2121) |

| Multiplicity | 6.6 (6.1) |

| Completeness (%) | 94.9 (85.7) |

| Mean I/σ(I) | 27.63 (5.4) |

| Wilson B factor (Å2) | 16.05 |

| R merge | 0.043 (0.129) |

| R meas | 0.047 |

| CC* | 1.00 (0.996) |

| R work | 0.1640 (0.1642) |

| R free | 0.2000 (0.2359) |

| CC(work) | 0.949 (0.955) |

| CC(free) | 0.928 (0.708) |

| No. of atoms | 3228 |

| No. of ligands | 0 |

| No. of waters | 212 |

| No. of protein residues | 386 |

| R.m.s.d., bonds (Å) | 0.010 |

| R.m.s.d., angles (°) | 1.42 |

| Ramachandran favored (%) | 97 |

| Ramachandran outliers (%) | 0 |

| Clash score | 2.71 |

| Average B factor (Å2) | 15.03 |

| Solvent content (%) | 43.15 |

Figure 2.

Comparison of CpXyn30A with similar GH30-8 enzymes. (a) Structural alignment of CpXyn30A (green) and BsXynC (cyan) visualized from the bottom showing the distinctive dual linker region which connects the side β-domain to the catalytic (α/β)8-barrel. (b) An extended α-helix associated with the α2 helix in CpXyn30A provides two additional stabilizing contacts not found in the other structurally characterized GH30-8 enzymes BsXynC or EcXynA (only BsXynC is shown in the figure for clarity). The one major interaction which is conserved involves the perpendicular ring stacking between Trp66 (Trp63 in BsXynC) and Tyr124 (Phe121 in BsXynC). This region of CpXyn30A additionally benefits from a similar perpendicular ring stacking between Trp58 and Tyr120 and also a hydrogen bond between Asp56 at the top of the loop and Ser93 extending down from the β3–α3 loop region. (c) The β3–α3 and β4–α4 loop region of CpXyn30A is homologous to that from other Gram-positive GH30-8 structures aligning closely with BsXynC but not with the Gram-negative model GH30-8 xylanase EcXynA (magenta).

Figure 3.

Differences between the β7–α7 and β8–α8 loop regions of CpXyn30A (green) and BsXynC (cyan) would not allow the coordination of GA residues. (a) Coordination of aldotriuronate into the BsXynC (PDB entry 3kl5) active site shows numerous contacts for which there is no equivalent interaction in the CpXyn30A structure. (b) Structure alignment of CpXyn30A and BsXynC shows the similar Cα trace between the two enzymes, with the alternative amino-acid side chains identified by CpXyn30A/BsXynC amino-acid numbering.

In the β1–α1 loop region, the sequence of CpXyn30A is shorter by three amino acids compared with BsXynC and the Gram-negative bacterial GH30-8 enzyme XynA from Erwinia chrysanthemi (EcXynA; PDB entry 1nof). A conserved tryptophan residue (Trp25) positioned by this loop establishes a predicted −3 xylosyl-binding subsite (St John et al., 2011 ▸; Urbániková et al., 2011 ▸). While the Cα position of this amino acid is shifted 3.4 Å towards the inside portion of the loop, the indole side chain lies in a similar position in all three enzymes, yielding a difference in their relative angle of approach which could alter the xylose subsite binding characteristics.

The β2–α2 loops of BsXynC and EcXynA are both very similar, but the analogous region of CpXyn30A is considerably larger owing to the presence of an additional nine amino acids. In all three enzymes, a single aromatic amino-acid stacking interaction is observed between residues in helices α2 and α3 (Fig. 2 ▸ b). The conserved interaction shared by these three xylanases consists of a phenylalanine (BsXynC and EcXynA) or tyrosine (Tyr124 in CpXyn30A) from the α3 helix in a perpendicular stacking arrangement with a tryptophan (Trp66 in CpXyn30A) extending from the α2 helix. The larger β2–α2 loop region unique to CpXyn30A provides two additional intramolecular contacts with adjacent regions of the enzyme. In the first interaction, Trp58 of CpXyn30A overlays the α3 helix and stacks perpendicular to Tyr120 (Fig. 2 ▸ b). The second interaction found in the extended loop region is a hydrogen bond between Asp56 and Ser93 of the β4–α4 loop region. These last two contacts are not found in the BsXynC or EcXynA enzymes and may serve a role in supporting the β-structured β3–α3 loop region as originally described for BsXynC but not EcXynA (Fig. 2 ▸ c; St John et al., 2011 ▸).

The β7–α7 loop region (Fig. 3 ▸) of CpXyn30A also displays a significantly different structure relative to the BsXynC and EcXynA enzymes. In this loop region of BsXynC and EcXynA, two conserved amino acids (Tyr231 and Ser235 in BsXynC) establish hydrogen bonds to the C-2 and C-3 hydroxyl groups of the α-1,2-linked GA appended onto the xylan chain (Fig. 3 ▸ a). In CpXyn30A, this loop is smaller in size but still has the conserved tyrosine (Tyr234). Following this amino acid, the loop region diverges slightly from the typical structure with Asp236 in place of a normally conserved serine and is positioned so as to make a functionally similar contact unlikely.

In the altered sequence of the β8–α8 loop, four of the GA-coordinating contacts identified in the ligand-bound BsXynC structure are no longer available (Fig. 3 ▸ b; St John et al., 2011 ▸). Surprisingly, despite the fact that the sequence of the β8–α8 loop region of CpXyn30A is completely different from the conserved sequence found in BsXynC and EcXynA, the structure of the loop does not significantly deviate from the Cα traces of these model enzymes. This is most noteworthy since this region forms the basis for classification of the proteins into the GH30-8 subfamily owing to its importance in GA recognition (Fig. 3 ▸ b).

3.3. Functional characterization

While CpXyn30A has measurable activity on glucuronoxylan, the specific activity is low relative to the characterized GH30-8 xylanases as well as other more common β-1,4-endoxylanases such as those from families GH10 and GH11. In consideration of this finding, other polymeric substrates were tested for activity. These included carboxymethylcellulose, barley β-glucan, yeast glucan, glucomannan, galactoglucomannan, xyloglucan and gum arabic, but in each case there was no detectable activity. The results presented in Table 2 ▸ indicate that CpXyn30A displays a similarly low specific activity on all xylan substrates tested. In studies employing X6 as a substrate at 12.1 mM (roughly the molar equivalence of 10 mg ml−1 xylan), CpXyn30A exhibits a similar activity as with 10 mg ml−1 SGX, a characteristic not previously observed for other GH30-8 enzymes (see below).

Table 2. Specific activity comparison of CpXyn30A and BsXynC on xylans and xylooligosaccharides.

Specific activity is given in units per milligram of protein, where one unit of activity is defined as one µmole per minute. The data resulted from triplicate measurements from a single assay. These results were consistent with numerous previous analyses. The given error is represented by the standard deviation.

| Substrates | Concentration | CpXyn30A | BsXynC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sweetgum glucuronoxylan (SGX) | 10.00 mg ml−1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 70.7 ± 4.8 |

| 7.50 mg ml−1 | 1.1 ± ≤0.1 | 61.7 ± 3.8 | |

| Wheat arabinoxylan (WAX) | 7.50 mg ml−1 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | nd† |

| Xylohexaose‡ (X6) | 12.10 mM | 1.19 ± ≤0.01 | 0.019 ± ≤0.002§ |

| Xylopentaose‡ (X5) | 12.10 mM | 0.36 ± ≤0.01 | ND¶ |

Not detected.

The data for these substrates represent an evaluation of specific activity based solely on the decrease in substrate. These values are higher than the true specific activity as the described competing transglycosylation reaction presumably consumes two X6 molecules. Xylohexaose was digested for 8 min and xylopentaose was digested for 20 min.

The X6 substrate concentration was only 10 mM for this reaction, a difference in the comparison which is considered to be inconsequential for this study.

Not determined.

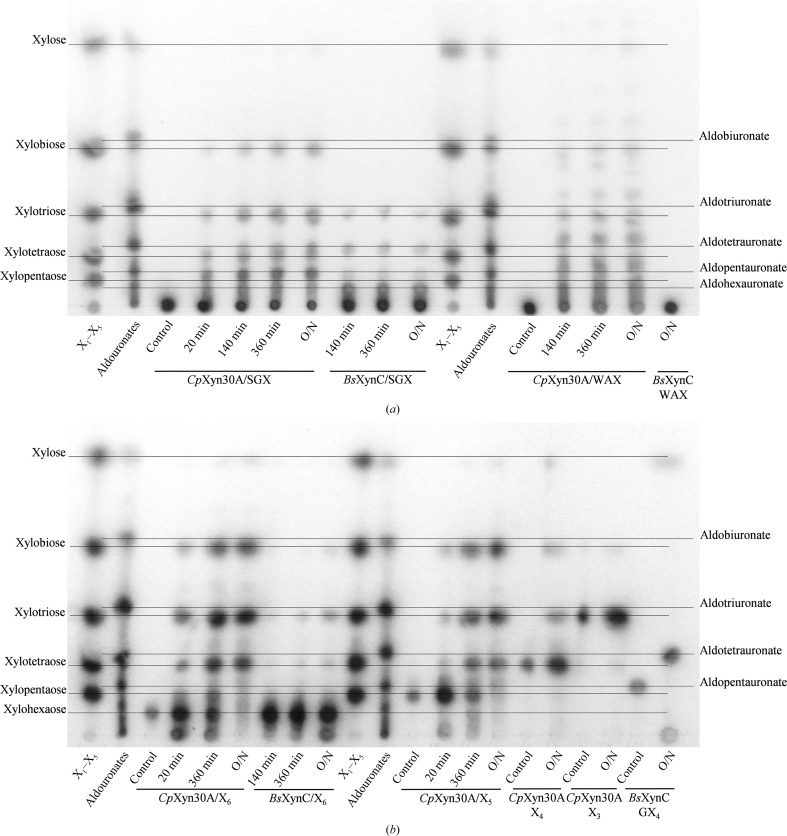

In TLC (Figs. 4 ▸ a and 4 ▸ b) analysis of an overnight hydrolysate of SGX by CpXyn30A, the xylooligosaccharides X2, X3 and X4 and the primary aldouronate GX4 were observed (Fig. 4 ▸ a). However, the uronic acid substitution position on the backbone xylotetraose of this aldouronate product remains unknown. CpXyn30A also efficiently processed WAX with only low levels of X2 and X3 apparent following an overnight digestion, although numerous other spots were observed on the plate which did not align with any of our standards. This suggests they are arabinofuranose-substituted xylooligosaccharides instead of neutral oligoxylosides. Hydrolysis of X6 and X5 resulted in a distribution of smaller xylooligosaccharides similar to those observed for glucuronoxylan hydrolysis, while X4 was weakly hydrolyzed (Fig. 4 ▸ b) and hydrolysis of X3 was not detected in overnight reactions (Figs. 4 ▸ b and 5 ▸ b).

Figure 4.

TLC analysis of CpXyn30A and BsXynC processing of (a) polymeric xylans and (b) xylooligosaccharides. Standards consist of X1–X5 lanes and lanes corresponding to the aldouronate series of sugars. Lanes are designated with times in minutes, where O/N indicates that the reaction was allowed to proceed overnight.

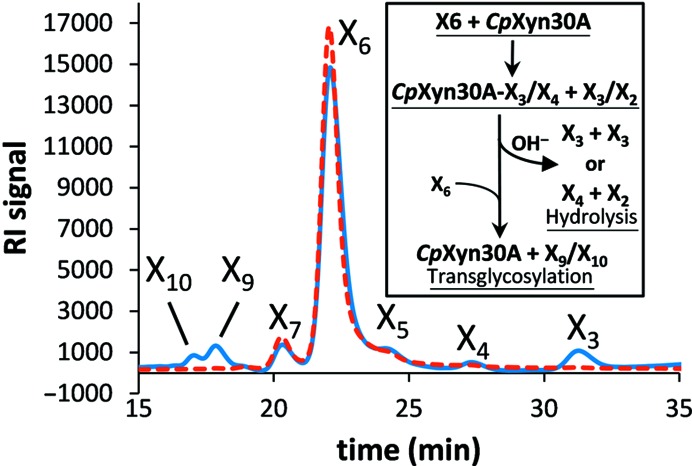

Figure 5.

HPLC analysis of xylooligosaccharide processing by CpXyn30A. A digestion of X6 (red) by CpXyn30A after 12 min (blue) showing the early reaction build-up of larger xylooligosaccharides. The inset describes the general course of a transglycosylation event in comparison to the typical hydrolytic event.

Activity measurements of BsXynC confirm the reported function of this enzyme as a glucuronoxylan xylanohydrolase which requires a substitution of α-1,2-linked GA residues for activity. Multiple attempts were made to obtain activity measurements for the hydrolysis of WAX by BsXynC, including one attempt which used a tenfold greater amount of enzyme than that used in similar reactions employing CpXyn30A and an overnight reaction time, but all results were generally too variable and close to zero to be reported as anything other than ‘not detected’ (Table 2 ▸). In agreement with previous findings, it is observed that BsXynC activity on X6 (10 mM) was three orders of magnitude (6172-fold) lower than on SGX (at 7.5 mg ml−1; Urbániková et al., 2011 ▸), thereby verifying the requirement for the GA substitution on the xylan chain for activity.

Parallel TLC studies of the reaction products generated by BsXynC also confirm our current understanding of these enzymes and have provided greater insight into their specificity (Figs. 4 ▸ a and 4 ▸ b). Hydrolysis of SGX by BsXynC yielded an array of aldouronate sugars (St John et al., 2006 ▸; Vršanská et al., 2007 ▸), while reactions containing WAX as substrate did not yield any detectable smaller sugars, a result supported by the lack of detectable enzymatic activity on this substrate in kinetic studies (Table 2 ▸). The TLC analysis of BsXynC hydrolysis of X6 visually confirms the results presented in Table 2 ▸, with a very low activity observed for hydrolysis of this substrate. In contrast to these observations, overnight hydrolysis of GX4 by BsXynC resulted in xylose and the smaller aldouronate aldotetrauronate (Fig. 4 ▸ b).

Xylooligosaccharide-hydrolysis studies showed that CpXyn30A has a competing transglycosylase activity (Shaikh & Withers, 2008 ▸). Following xylooligosaccharide hydrolysis and formation of the enzyme–substrate complex, if a sugar molecule were to bind in the active-site cleft in place of the catalytic water, then the C-4 hydroxyl group of the nonreducing terminal residue may become activated, resulting in a transglycosylation reaction creating a new β-1,4-xylosidic bond. For retaining glycoside hydrolases such as GH30 enzymes, transglycosylation occurs as a product of a failed hydrolytic reaction.

In the present study, hydrolysis of X6 by CpXyn30A results in what is predicted from HPLC chromatograms to be xylodecaose (X10) and xylononaose (X9) as well as smaller xylooligosaccharides such as X2 through X4 (Fig. 5 ▸ and inset). These data were confirmed by TLC analysis, which showed that within 20 min of the start of the reaction hydrolysis of X6 resulted in a spot with no mobility [estimated DP (degree of polymerization) > 8] and small amounts of X4, X3 and X2. Formation of X10 and X9 may occur through a transglycosylation when CpXyn30A cleaves X6 such that either a X3 or X4 is positioned in the glycone side of the substrate binding cleft in the enzyme–substrate complex (Fig. 5 ▸, inset). Because xylooligosaccharides smaller than X5 are not hydrolyzed they cannot be a source of further transglycosylation. Based on this analysis, specific activities are anticipated to be lower than reported (Table 2 ▸), as the enzyme-catalyzed transglycosylation reaction consumes two molecules of X6. It is impossible to determine what the ratio of hydrolysis to transglycosylation reactions might be without quantification of X9 and X10.

Transglycosylation is not likely to contribute substantially during the hydrolysis of polymeric xylan, as the concentration of reducing termini is much lower and is unlikely to significantly compete as an acceptor through the limited reaction time. Studies meant to assess the pH dependence of the transglycosylation reaction verified that it coincided perfectly with the optimum hydrolysis pH of the enzyme (data not shown).

Interestingly, even though the model enzyme BsXynC only hydrolyzes neutral xylooligosaccharides such as X6 very slowly, the limited activity that was observed appears from TLC to result in part from transglycosylation, similar to CpXyn30A (Fig. 4 ▸ b). Similar results were previously reported for another GH30-8 Gram-positive enzyme (a highly conserved homolog from Bacillus sp. strain BP-7; Gallardo et al., 2010 ▸). In this report, enzyme activities were not provided for comparison with the data in Table 2 ▸, but our data on the rate of hydrolysis of X6 agree with the previously reported level of activity for the Gram-negative GH30-8 enzyme EcXynA, having a three-order lower activity on this neutral xylooligosaccharide than on a polymeric glucuronoxylan substrate (Urbániková et al., 2011 ▸). Transglycosylation can also be observed by TLC following the overnight digestion of GX4, indicating that BsXynC may be producing disubstituted aldouronates (Fig. 4 ▸ b).

Clues to the distinctive comparative function of these enzymes may be ascertained from their structures. Of the five hydrogen bonds and one salt bridge that have been described which establish the interaction between the β7–α7 and β8–α8 loops and the GA side chain in the BsXynC and EcXynA enzymes, only two hydrogen bonds are thought to be possible in CpXyn30A. These positions, which are equivalent to Tyr234 and Trp265 in CpXyn30A, may be available for hydrogen bonding with either GA or arabinofuranose substitutions linked α-1,2 on the main xylan chain. However, since activity measurements are similar on neutral xylooligosaccharides and xylans, it seems unlikely that these potential hydrogen-bonding positions play a significant role in xylan hydrolysis. Instead, the β8–α8 loop contains larger, hydrophobic amino acids, which would appear from inspection of a surface analysis to displace the xylose and any substitution in the −2 subsite position. Because of this displacement, substitutions in this region are most likely to be beyond hydrogen-bonding distance of Tyr234 and Trp265. The increased size of the β8–α8 loop may reorient the glycone-bound xylan sugar out of an ideal orientation for hydrolysis.

CpXyn30A is the first example of a GH30-8 xylanase that does not require the recognition of a GA substitution for hydrolysis to occur. This finding correlates well with the functional variability reported in the closely related GH30-7 subfamily (Biely et al., 2014 ▸; Tenkanen et al., 2013 ▸), with the major difference being that GH30-7 enzymes are primarily fungal in origin while GH30-8 enzymes are primarily bacterial. These two GH30 xylanase subfamilies are distinguished by their functional and amino-acid sequence diversity, which brings special focus to their potential in xylanase development.

From these data, CpXyn30A stands out as a unique GH30-8 xylanase with no apparent specificity for O-2-linked GA substitutions and with a relatively low specific activity on the common xylan substrates SGX, WAX and the neutral xylooligosaccharide X6. Although considered to be low, the rate of hydrolysis for these substrates was about 70-fold greater than the rate at which the canonical GH30-8 endoxylanase BsXynC is able to process X6 owing to its requirement for GA recognition. Even though CpXyn30A has a demonstrated xylanase activity, it is not known whether the enzyme represents an evolved functionality whose role has not been precisely identified or a residual xylanase activity resulting from nonbeneficial changes to the xyn30A gene in C. papyrosolvens. It seems likely that the conserved sequence of the β7–α7 and β8–α8 loops found in the BsXynC/EcXynA enzymes enable recognition and therefore endow specificity for the α-1,2-linked GA substitution on the xylan chain, but are not likely to have a prominent role in allowing hydrolysis of the β-1,4-xylosidic linkage of xylan.

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: Clostridium papyrosolvens Xyn30A, 4fmv

Acknowledgments

This work was primarily supported through the Wood, Fiber and Composites Research area of the USDA Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory, Madison, Wisconsin, USA. JCH is supported by a grant from the National Center for Research Resources (5 P20 RR016461). JCH would like to acknowledge Dr Chris Davies of the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina, USA for access to X-ray equipment and assistance in data collection.

References

- Adams, P. D. et al. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 213–221.

- Bateman, A., Coin, L., Durbin, R., Finn, R. D., Hollich, V., Griffiths-Jones, S., Khanna, A., Marshall, M., Moxon, S., Sonnhammer, E. L., Studholme, D. J., Yeats, C. & Eddy, S. R. (2004). Nucleic Acids Res. 32, D138–D141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Battye, T. G. G., Kontogiannis, L., Johnson, O., Powell, H. R. & Leslie, A. G. W. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 271–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Biely, P., Puchart, V., Stringer, M. A. & Mørkeberg Krogh, K. B. (2014). FEBS J. 281, 3894–3903 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Biely, P., Vrsanská, M., Tenkanen, M. & Kluepfel, D. (1997). J. Biotechnol. 57, 151–166. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Blumenkrantz, N. & Asboe-Hansen, G. (1973). Anal. Biochem. 54, 484–489. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bounias, M. (1980). Anal. Biochem. 106, 291–295. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cantarel, B. L., Coutinho, P. M., Rancurel, C., Bernard, T., Lombard, V. & Henrissat, B. (2009). Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D233–D238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- DeLano, W. L. (2002). PyMOL. http://www.pymol.org.

- DuBois, M., Gilles, K. A., Hamilton, J. K., Rebers, P. A. & Smith, F. (1956). Anal. Chem. 28, 350–356.

- Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Evans, P. (2006). Acta Cryst. D62, 72–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gallardo, Ó., Fernández-Fernández, M., Valls, C., Valenzuela, S. V., Roncero, M. B., Vidal, T., Díaz, P. & Pastor, F. I. (2010). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 6290–6294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gasteiger, E., Hoogland, C., Gattiker, A., Duvaud, S., Wilkins, M. R., Appel, R. D. & Bairoch, A. (2005). The Proteomics Protein Handbook, edited by J. M. Walker, pp. 571–607. Totowa: Humana Press.

- Gouet, P., Robert, X. & Courcelle, E. (2003). Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3320–3323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Henrissat, B. (1998). Biochem. Soc. Trans. 26, 153–156. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hurlbert, J. C. & Preston, J. F. (2001). J. Bacteriol. 183, 2093–2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Katoh, K. & Toh, H. (2008). Brief. Bioinform. 9, 286–298. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Laemmli, U. K. (1970). Nature (London), 227, 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Larson, S. B., Day, J., Barba de la Rosa, A. P., Keen, N. T. & McPherson, A. (2003). Biochemistry, 42, 8411–8422. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Marchler-Bauer, A. et al. (2011). Nucleic Acids Res. 39, D225–D229.

- McCoy, A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Adams, P. D., Winn, M. D., Storoni, L. C. & Read, R. J. (2007). J. Appl. Cryst. 40, 658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nelson, N. (1944). J. Biol. Chem. 153, 375–379.

- Petersen, T. N., Brunak, S., von Heijne, G. & Nielsen, H. (2011). Nature Methods, 8, 785–786. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ren, J., Wen, L., Gao, X., Jin, C., Xue, Y. & Yao, X. (2009). Cell Res. 19, 271–273. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Shaikh, F. A. & Withers, S. G. (2008). Biochem. Cell Biol. 86, 169–177. [DOI] [PubMed]

- St John, F. J., Godwin, D. K., Preston, J. F., Pozharski, E. & Hurlbert, J. C. (2009). Acta Cryst. F65, 499–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- St John, F. J., González, J. M. & Pozharski, E. (2010). FEBS Lett. 584, 4435–4441. [DOI] [PubMed]

- St John, F. J., Hurlbert, J. C., Rice, J. D., Preston, J. F. & Pozharski, E. (2011). J. Mol. Biol. 407, 92–109. [DOI] [PubMed]

- St John, F. J., Rice, J. D. & Preston, J. F. (2006). J. Bacteriol. 188, 8617–8626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K., Stecher, G., Peterson, D., Filipski, A. & Kumar, S. (2013). Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tenkanen, M., Vršanská, M., Siika-aho, M., Wong, D. W., Puchart, V., Penttilä, M., Saloheimo, M. & Biely, P. (2013). FEBS J. 280, 285–301. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Urbániková, L., Vršanská, M., Mørkeberg Krogh, K. B., Hoff, T. & Biely, P. (2011). FEBS J. 278, 2105–2116. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Vršanská, M., Kolenová, K., Puchart, V. & Biely, P. (2007). FEBS J. 274, 1666–1677. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Welch, M., Govindarajan, S., Ness, J. E., Villalobos, A., Gurney, A., Minshull, J. & Gustafsson, C. (2009). PLoS One, 4, e7002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: Clostridium papyrosolvens Xyn30A, 4fmv