Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Treatment of severe hypoglycemia with loss of consciousness or seizure outside of the hospital setting is presently limited to intramuscular glucagon requiring reconstitution immediately prior to injection, a process prone to error or omission. A needle-free intranasal glucagon preparation was compared with intramuscular glucagon for treatment of insulin-induced hypoglycemia.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

At eight clinical centers, a randomized crossover noninferiority trial was conducted involving 75 adults with type 1 diabetes (mean age, 33 ± 12 years; median diabetes duration, 18 years) to compare intranasal (3 mg) versus intramuscular (1 mg) glucagon for treatment of hypoglycemia induced by intravenous insulin. Success was defined as an increase in plasma glucose to ≥70 mg/dL or ≥20 mg/dL from the glucose nadir within 30 min after receiving glucagon.

RESULTS

Mean plasma glucose at time of glucagon administration was 48 ± 8 and 49 ± 8 mg/dL at the intranasal and intramuscular visits, respectively. Success criteria were met at all but one intranasal visit and at all intramuscular visits (98.7% vs. 100%; difference 1.3%, upper end of 1-sided 97.5% CI 4.0%). Mean time to success was 16 min for intranasal and 13 min for intramuscular (P < 0.001). Head/facial discomfort was reported during 25% of intranasal and 9% of intramuscular dosing visits; nausea (with or without vomiting) occurred with 35% and 38% of visits, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS

Intranasal glucagon was highly effective in treating insulin-induced hypoglycemia in adults with type 1 diabetes. Although the trial was conducted in a controlled setting, the results are applicable to real-world management of severe hypoglycemia, which occurs owing to excessive therapeutic insulin relative to the impaired or absent endogenous glucagon response.

Introduction

Hypoglycemia is a major barrier to the attainment of glycemic control targets in patients with diabetes (1). Patients with type 1 diabetes bear the greatest burden of problematic hypoglycemia. In such patients, mild-to-moderate hypoglycemia (blood glucose 50–70 mg/dL) occurs frequently and responds in most cases to oral carbohydrate administration (2,3). However, further reductions in blood glucose can lead to hypoglycemia-induced cognitive dysfunction, which may make it impossible for an individual to take appropriate corrective measures to restore normal blood glucose (4). In the most severe hypoglycemic events, administration of oral carbohydrate by a second party is precluded because the patient is combative, unconscious, or having a seizure. Such severe hypoglycemia, which is not uncommon, can be associated with significant morbidity (5) and mortality (6). In the T1D Exchange registry, about 1 in 10 participants reported hypoglycemia-related seizure or loss of consciousness in the prior year, with an even higher annual frequency (1 in 5) for those with >40 years’ diabetes duration (7). Other studies have reported similar frequencies (8,9).

Treatment of severe hypoglycemia should be administered when possible by bystanders while awaiting emergency medical services and currently involves parenteral administration of glucagon. Glucagon, the principal counterregulatory hormone to insulin, is inhibited by insulin and fails to activate in response to hypoglycemia in patients with type 1 diabetes (10,11). Current commercially available glucagon preparations are unstable in solution and available only as a lyophilized powder that must be reconstituted in diluent immediately prior to injection. Thus, glucagon is often not available when needed and, even when available, may be improperly administered owing to the complexity of the preparation and administration processes (12). Thus, alternative delivery systems for the administration of glucagon for severe hypoglycemia are needed.

More than 20 years ago, several small studies demonstrated the ability of intranasally administered glucagon solution or powder to increase plasma glucose levels in healthy volunteers (13) in a dose-dependent fashion (14) and to correct insulin-induced hypoglycemia in patients with type 1 diabetes (14–17). None of these studies led to commercialization of a nonparenteral glucagon preparation. In the current study, we evaluated the efficacy and safety of a novel intranasal glucagon delivery system in comparison with standard intramuscular glucagon for the treatment of insulin-induced hypoglycemia in adults with type 1 diabetes.

Research Design and Methods

The study was conducted at eight diabetes clinics within the T1D Exchange Clinic Network (18). Participants included men and women aged 18–64 years with type 1 diabetes of at least 2 years’ duration and weighing ≥50 kg with BMI 20–35 kg/m2. Exclusion criteria included history of a severe hypoglycemic episode in the month prior to enrollment, pheochromocytoma, or insulinoma; history of seizure disorder; cardiovascular, liver, or kidney disease; use of a β-blocker; or consumption of three or more alcoholic beverages daily. Additional protocol details are available at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01994746). The Institutional Review Board of each participating institution approved the study protocol, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Enrolled participants underwent two glucagon dosing visits, scheduled 1–4 weeks apart. Participants were randomly assigned to receive either 3 mg intranasal glucagon (Locemia Solutions) or 1 mg intramuscular glucagon (GlucaGen HypoKit [Novo Nordisk]) (19) during the first dosing visit, with the other glucagon preparation administered during the second dosing visit in a crossover fashion using a block design stratified by clinic; the randomization sequence was generated by the coordinating center and revealed to clinic center staff using a central study Web site upon enrollment of each participant. The intranasal glucagon formulation consisted of 3 mg glucagon, the phospholipid dodecylphosphocholine as an absorption enhancer, and β-cyclodextrin as a bulking agent in a total dose mass of 30 mg powder, contained within a single-use one-step dispensing device. The tip of the device was inserted in one nostril, and the dose was delivered by simply depressing a plunger connected to a piston that gently discharges the powder into the nostril (Supplementary Fig. 1). No inhalation or other cooperative measure is required from the patient, as absorption takes place through the nasal mucosa. An earlier phase I study showed nasal congestion, with or without concomitant use of a decongestant, did not adversely affect glucagon pharmacokinetics or the glycemic response in otherwise healthy subjects given the 3-mg dose during and after recovery from a common cold (C.A. Piché, written communication). A phase II study established a dose response for intranasal glucagon that attained a maximal increase in blood glucose with the 3-mg dose, presumably due to saturable absorption across the nasal mucosa (20).

Each glucagon dosing visit was conducted after an overnight fast of at least 8 h with a starting plasma glucose ≥90 mg/dL. Hypoglycemia was induced by an infusion of insulin initially at 2 mU/kg/min i.v. that could be increased to 3 mU/kg/min or decreased to 1.5 or 1 mU/kg/min as necessary to achieve a controlled decline in plasma glucose. For participants using an insulin pump, the continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion was suspended during the procedure, while participants using multiple daily injections of insulin took their last long-acting insulin dose the day before testing. Plasma glucose concentrations were measured every 5–10 min after the start of the insulin infusion using a U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved glucose analyzer (YSI 2300, Yellow Springs Instruments, Yellow Springs, OH; Beckman, Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA; Analox GM9, Analox Instruments, Lunenburg, MA; or HemoCue, HemoCue Worldwide, Ängelholm, Sweden). Once the glucose concentration was <60 mg/dL, the insulin infusion was stopped, and 5 min later blood samples for glucose and glucagon were collected and glucagon was administered at t = 0. Glucagon was delivered with the subject lying in a lateral recumbent position either in the deltoid muscle of the nondominant arm for the intramuscular administration or nare of the same side for the intranasal administration. Serial blood samples for glucose and glucagon were collected at t = 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 40, 50, 60, and 90 min. Insulin was measured at t = 0, 30, and 60 min. Hypoglycemia symptoms were assessed by the Edinburgh Hypoglycemia Scale (21) at baseline, once the glucose was <75 and <60 mg/dL, and at t = 15, 30, 45, and 60 min after the administration of glucagon. Nasal and nonnasal symptoms were ascertained at baseline and at t = 15, 30, 60, and 90 min after glucagon administration.

Biochemical Analysis

All samples for analysis of glucose, glucagon, and insulin were collected on ice into tubes containing EDTA with the protease inhibitor aprotinin immediately added, centrifuged at 4°C, separated, and frozen at −80°C until subsequent analysis. Plasma glucose concentrations were measured by the glucose hexokinase method using an automated glucose analyzer (Roche Module P; Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), insulin by two site immune-enzymometric assay using a Tosoh 2000 auto-analyzer (Tosoh Biosciences, San Francisco, CA), and glucagon by a commercially available radioimmunoassay (Millipore, Billerica, MA) at the Northwest Lipid Research Laboratories (University of Washington, Seattle, WA).

Statistical Analysis

Treatment success was defined as an increase in plasma glucose to ≥70 mg/dL or an increase of ≥20 mg/dL from the glucose nadir within 30 min after receiving study glucagon, without receiving additional actions to increase the plasma glucose level. This success criteria accounts for the treatment goal to either normalize glycemia or raise the glucose to a level above which cognitive function would allow further treatment with oral carbohydrate. The sample size was computed to be 75 individuals completing both dosing visits under the following assumptions: success rate of 95% in each treatment arm, noninferiority limit of 10%, one-sided α of 0.025, and 80% power. It was preplanned to replace and not include in efficacy analyses participants who did not have two valid dosing visits, defined as receipt of study glucagon (intramuscular or intranasal) and no rescue treatment for severe hypoglycemia prior to or within the first 10 min after glucagon administration. Safety analyses included all dosing visits in which glucagon was received.

All reported glucose and glucagon concentrations are from the central laboratory, except for 3 instances out of 1,650 for which the central lab glucose measurement was missing and a local glucose measurement was used. Nadir glucose concentration was defined as the minimum glucose measurement within 10 minutes after glucagon administration. A treatment comparison of nadir glucose concentration was completed using a t test.

The proportion of successes in each treatment arm and the difference in proportions were computed, and a one-sided 97.5% CI was obtained from the one-sample mean of the paired differences in outcomes (outcome observed, 1; outcome not observed, 0) across dosing visits. The difference in proportion of successes between treatment arms and one-sided 97.5% CI also was calculated using a Poisson regression model incorporating a generalized estimating equation with adjustments for nadir glucose and treatment period (first treatment for participant versus second treatment for participant).

Summary statistics for plasma glucose concentrations at each time point across the dosing visit were calculated with imputation for missing glucose values and glucose values after receipt of intervention treatment using the Rubin method based on available glucose measurements and treatment arm. A treatment comparison of the blood glucose concentration over the 90 min after administration of glucagon was performed using a linear mixed model with repeated measures.

A treatment arm comparison of the time from administration of glucagon to occurrence of success was performed for the subset of dosing visits with nadir glucose concentration <50 mg/dL by constructing Kaplan-Meier curves and by using the marginal Cox proportional hazards model for clustered data adjusting for nadir blood glucose and treatment period. If a participant received additional intervention treatment to raise the glucose concentration prior to success, the remaining time points were considered failures. Missing glucose values were imputed using the Rubin method based on available lab glucose measurements and treatment arm.

Peak glucagon concentrations were compared between treatment groups using an ANOVA model with participant included as a random effect. A treatment comparison of time to peak glucagon concentration was performed using a Wilcoxon signed rank test. Three glucagon values were removed from the analysis owing to suspected sample collection error; these glucagon values were imputed using the Rubin method based on available glucagon measurements and treatment arm.

A treatment comparison of the Edinburgh Hypoglycemia Scale score at each time point after glucagon administration was completed using linear mixed models with repeated measures adjusting for the treatment period and score at visit arrival. Similarly, a treatment comparison of the occurrence of nausea, with or without vomiting, was completed using a generalized linear mixed model with random participant effect.

Results are expressed as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range). Data analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Between December 2013 and May 2014, 75 participants successfully completed both dosing visits and were included in the efficacy analyses, and 77 completed at least one dosing visit and were included in the safety analyses (Supplementary Fig. 1). Among the 77 included in the analyses, mean ± SD age was 33 ± 12 years and BMI 26 ± 4 kg/m2 and 45 (58%) were female and 74 (96%) non-Hispanic white. Median duration of type 1 diabetes was 18 (interquartile range 9–25) years; 57 (74%) were using an insulin pump and the rest multiple daily injections of insulin. Mean HbA1c was 8.3 ± 1.8% (Supplementary Table 1). Among the 75 who successfully completed both dosing visits, 72 (96%) were non-Hispanic white.

Median time between the two dosing visits was 16 (interquartile range 14–22) days. The median total amount of insulin given to induce hypoglycemia was 0.09 (0.07–0.13) units/kg for the intranasal glucagon visits and 0.10 (0.08–0.14) units/kg for the intramuscular glucagon visits. Plasma insulin levels 0, 30, and 60 min after glucagon administration were similar between arms (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study protocol characteristics by treatment arm

| Intranasal (N = 75) | Intramuscular (N = 75) | |

|---|---|---|

| Central lab glucose concentration immediately prior to glucagon administration (mg/dL) | ||

| 20 to <30 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| 30 to <40 | 9 (12) | 7 (9) |

| 40 to <50 | 28 (37) | 31 (41) |

| 50 to <60 | 34 (45) | 28 (37) |

| 60 to <70 | 3 (4) | 8 (11) |

| ≥70 | 0 | 0 |

| Mean ± SD | 48 ± 8 | 49 ± 8 |

| Difference (intramuscular – intranasal), mean ± SD | 1 ± 9 | |

| Central lab glucose at nadir (mg/dL)a | ||

| 20 to <30 | 3 (4) | 2 (3) |

| 30 to <40 | 17 (23) | 11 (15) |

| 40 to <50 | 38 (51) | 31 (41) |

| 50 to <60 | 15 (20) | 28 (37) |

| 60 to <70 | 2 (3) | 3 (4) |

| ≥70 | 0 | 0 |

| Mean ± SD | 44 ± 8 | 47 ± 8 |

| Difference (intramuscular – intranasal), mean ± SD | 3 ± 9 | |

| Insulin infusion | ||

| Local glucose concentration when insulin infusion initiated (mg/dL), mean ± SD | 161 ± 48 | 165 ± 54 |

| Local glucose concentration when insulin infusion discontinued (mg/dL), mean ± SD | 55 ± 5 | 55 ± 4 |

| Duration of insulin infusion (min), median (25th–75th percentile) | 54 (41–72) | 60 (42–80) |

| Amount of insulin received prior to discontinuation (units/kg), median (25th–75th percentile)b | 0.09 (0.07–0.13) | 0.10 (0.08–0.14) |

| Lab insulin concentration (μU/mL), median (25th–75th percentile) | ||

| Prior to glucagon administrationc | 55.3 (35.6–72.2) | 53.5 (36.5–69.6) |

| 30-min postglucagon administrationd | 11.8 (7.0–22.5) | 12.9 (7.5–17.8) |

| 60-min postglucagon administratione | 6.5 (4.3–14.1) | 7.1 (4.9–10.9) |

Data are n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

aMinimum central lab glucose concentration measured after glucagon administration; nadir occurred at time 0 for 13 (17%) participants receiving intranasal glucagon and 49 (65%) participants receiving intramuscular glucagon, at time 5 min for 59 (79%) participants receiving intranasal glucagon and 25 (33%) participants receiving intramuscular glucagon, and at time 10 min for 3 (4%) participants receiving intranasal glucagon and 1 (1%) participant receiving intramuscular glucagon; P = 0.002 from a t test for the treatment comparison of nadir glucose.

bTotal amount of insulin received during the insulin infusion, including the priming dose of insulin (if a priming dose was given); 14 (19%) participants in the intranasal glucagon arm received a priming dose of insulin (mean ± SD priming insulin dose 0.03 ± 0.01 units/kg), and 16 (21%) participants in the intramuscular glucagon arm received a priming dose of insulin (mean ± SD priming insulin dose 0.04 ± 0.02 units/kg).

cSix of 160 measurements were removed from the analysis owing to potential sample collection error (3 intranasal glucagon dosing visits and 3 intramuscular glucagon dosing visits).

dMissing for 1 intramuscular glucagon dosing visit.

eFour of 160 values were not included in the analysis owing to potential sample collection error (1 intranasal glucagon dosing visit and 3 intramuscular glucagon dosing visits).

At the time of insulin infusion discontinuation, mean ± SD local glucose concentration was 55 ± 5 and 55 ± 4 mg/dL for the intranasal and intramuscular dosing visits, respectively. Mean central laboratory glucose concentrations were 48 ± 8 mg/dL and 49 ± 8 mg/dL, respectively, 5 min after stopping insulin immediately prior to glucagon administration (t= 0) and 44 ± 8 mg/dL and 47 ± 8 mg/dL, respectively, at the nadir (Table 1). The nadir glucose concentration occurred at t=0 for most intramuscular glucagon visits (49 of 75 visits [65%]) and at t = 5 for most intranasal visits (59 of 75 visits [79%]).

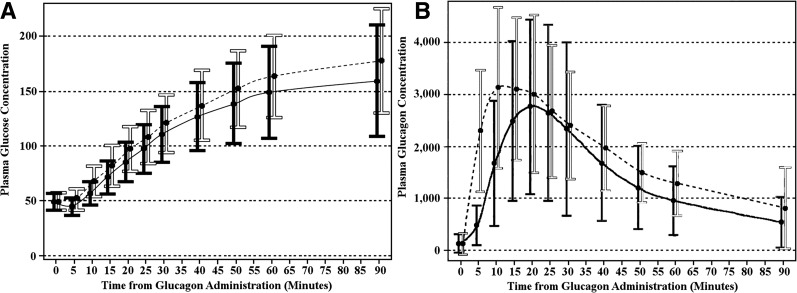

Success criteria were met on 74 of the 75 (98.7%) intranasal glucagon visits and all 75 (100%) of the intramuscular glucagon visits (unadjusted difference 1.3%, one-sided 97.5% CI 4.0%; adjusted difference 1.5%, one-sided 97.5% CI 4.3%). The one intranasal dosing visit not meeting success criteria had a nadir glucose concentration of 47 mg/dL with a rise by 30 min to 65 mg/dL and by 40 min to 72 mg/dL without any other intervention. As can be seen in Fig. 1A, the rise in glucose concentrations after intranasal glucagon lagged behind the rise after intramuscular glucagon by ∼5 min (P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Plasma glucose (A) and glucagon (B) concentrations over time according to treatment visit. Data are mean ± SD, with the solid black bars and line representing the intranasal visit and the white bars and black dotted line representing the intramuscular visit.

Within 5 min of administration of both products, glucagon levels had reached pharmacological levels indicating rapid absorption via both routes of administration. Initially, glucagon concentrations after intranasal administration were lower than concentrations after intramuscular with the mean ± SD peak 3,155 ± 1,956 and 3,672 ± 1,726 pg/mL (P = 0.003) and median (minimum, maximum) time to peak 20 min (10, 90) and 15 min (5, 60) (P < 0.001), respectively, but were not different after 20 min (Fig. 1B).

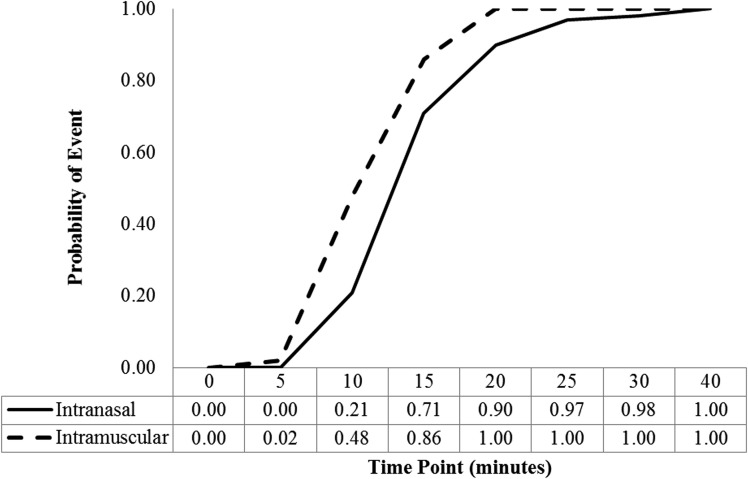

Examination of only dosing visits where the nadir glucose was <50 mg/dL (Fig. 2) shows that time to success after intranasal glucagon lagged slightly behind time to success after intramuscular glucagon (mean times to reach 70 mg/dL or 20 mg/dL increase were 16 min and 13 min with intranasal glucagon and intramuscular glucagon, respectively; P < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Time to plasma glucose concentration ≥70 mg/dL or an increase ≥20 mg/dL from nadir concentration in participants with nadir glucose <50 mg/dL. N: intranasal 58 (77%) and intramuscular 44 (59%).

Symptoms of hypoglycemia, as represented by Edinburgh Hypoglycemia Scale scores, were greater in the intranasal group compared with the intramuscular group for the first 45 min after administration but similar thereafter (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Transient head or facial discomfort was reported after 19 (25%) intranasal glucagon administrations and after 7 (9%) intramuscular administrations. Vomiting occurred after 13 (17%) intranasal and 9 (12%) intramuscular administrations; nausea without vomiting occurred during an additional 14 (18%) intranasal and 20 (26%) intramuscular administrations (P = 0.59) (nausea, with or without vomiting, after intranasal glucagon administration [36%] vs. intramuscular administration [38%]) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adverse events by treatment visita

| Adverse event group | Intranasal (N = 77) | Intramuscular (N = 76) |

|---|---|---|

| GI | ||

| Abdominal discomfort | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Nausea | 17 (22) | 21 (28) |

| Vomiting | 13 (17) | 9 (12) |

| Total (≥1 GI events)b | 28 (36) | 29 (38) |

| Head discomfort | ||

| Ear pain | 2 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Eye pain | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Facial pain | 2 (3) | 0 |

| Headache | 18 (23) | 7 (9) |

| Neck pain | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Total (≥1 head pain events)b | 19 (25) | 7 (9) |

| Nasal | ||

| Nasal congestion | 6 (8) | 1 (1) |

| Nasal discomfort | 8 (10) | 0 |

| Nasal edema | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Rhinorrhoea | 2 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Total (≥1 nasal events)b | 14 (18) | 1 (1) |

| Weakness/fatigue | ||

| Fatigue | 6 (8) | 5 (7) |

| Lethargy | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Muscular weakness | 2 (3) | 0 |

| Total (≥1 weakness/fatigue events)b | 8 (10) | 6 (8) |

| Ocular | ||

| Eye pruritus | 2 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Lacrimation increased | 7 (9) | 1 (1) |

| Ocular hyperemia | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Total (≥1 ocular events)b | 7 (9) | 1 (1) |

| Cognitive | ||

| Confusional state | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Disturbance in attention | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Somnolence | 2 (3) | 0 |

| Total (≥1 cognitive events)b | 2 (3) | 0 |

| Autonomic | ||

| Hot flush | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Hyperhidrosis | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Total (≥1 autonomic events)b | 1 (1) | 2 (3) |

| Throat | ||

| Cough | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Upper-airway cough syndrome | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Total (≥1 throat events)b | 2 (3) | 0 |

| Skin: pruritus | 2 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Hyperglycemia | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Psychological: anxiety | 1 (1) | 0 |

Data are n (%). No serious adverse events were reported. GI, gastrointestinal.

aForty-four (57%) of 77 participants receiving intranasal glucagon experienced at least 1 adverse event; 35 (46%) of 76 participants receiving intramuscular glucagon experienced at least 1 adverse event.

bTotal number (%) of participants with at least 1 occurrence of the adverse event group.

Conclusions

In the study, intranasal glucagon consistently corrected insulin-induced hypoglycemia in adults with type 1 diabetes, meeting the predefined definition of noninferiority to intramuscular injection of glucagon. In the one case in which intranasal glucagon did not meet the study-defined success criteria, hypoglycemia was corrected without any additional intervention but after the time frame for study-defined success. Average glucose concentrations and time to meet the primary end point after intranasal glucagon lagged ∼3 min behind glucose concentrations after intramuscular glucagon, consistent with the glucagon concentrations showing a relative delay in achievement of peak glucagon levels with intranasal glucagon of ∼5 min. Nevertheless, pharmacologic levels of glucagon were present by 5 min after administration by either approach. The slight delay in glycemic response would likely be clinically inconsequential and in many circumstances might be offset by the time required, errors, and failures to deliver among nonmedical caregivers in preparing and administering the injectable intramuscular formulation. Indeed, a recent human factors study simulating treatment of severe hypoglycemia shows nasal delivery of glucagon is much faster with a higher success rate than injection for trained caregivers of insulin-using persons (16 s vs. 1.9 min for time to administer, 94% vs. 50% for delivery) and for untrained acquaintances (26 s vs. 2.4 min, 93% vs. 20% for delivery) for intranasal and intramuscular dosings, respectively (22).

Several small studies have documented the ability of intranasally sprayed glucagon to increase plasma glucose levels in healthy volunteers (13) in a dose-dependent fashion (14) and to correct insulin-induced hypoglycemia in patients with type 1 diabetes (14–16). In the case of glucagon administration for the treatment of severe hypoglycemia, impaired or absent consciousness would prevent patient inhalation of sprayed solution to assist with absorption. Another small study tested the response to insulin-induced hypoglycemia in patients with type 1 diabetes using a dry powder formulation containing either 1 or 2 mg glucagon and found similar pharmacodynamics with the 2-mg dose of glucagon compared with 1 mg glucagon administered intramuscularly (17). In these prior reports, the glucose-raising effect of intranasal glucagon was similar in onset but of shorter duration compared with intramuscular administration (13,15,17). In our study, 3 mg intranasal glucagon exhibited equivalent durability of the glucose-raising effect as with intramuscular glucagon for the 90-min postdosing observation period.

In the current study, there was a delay in resolution of hypoglycemia symptoms at the intranasal compared with intramuscular dosing visit; however, the magnitude of hypoglycemia symptoms was not different between visits, likely because of the similar nadir glucose levels achieved. While we did not measure plasma epinephrine, given the comparable degree of autonomic symptom generation and the pharmacologic levels of glucagon present by 5 min under both dosing conditions, we do not believe other counterregulatory hormones played a significant role in this study. As expected, transient nasal symptoms and head or facial discomfort occurred more frequently with the intranasal preparation. However, in the setting in which intranasal glucagon is given to an individual with severe cognitive impairment and often loss of consciousness, this will not be relevant. Nausea and vomiting, well-known consequences of glucagon administration owing to relaxation of gastrointestinal smooth muscle (23), occurred at similar frequencies with both glucagon preparations.

This study had certain limitations. The glucagon dosing administration was not blinded. Although this could have influenced investigator handling of the insulin infusion protocol to induce hypoglycemia, there was no evidence of bias, since the actual amounts of insulin administered, as well as the preglucagon dosing insulin and glucose levels, were nearly identical between the study visits. The study lacked a sham treatment condition that would have controlled for possible spontaneous recovery from hypoglycemia. However, hospital policies preclude not treating hypoglycemia <40 mg/dL, and with this degree of hypoglycemia experienced during 27% and 18% of the intranasal and intramuscular glucagon dosing visits, respectively, a very high rate of rescue treatment would have been required without an intervention. It was also not ethical to reduce glucose levels to the point of seizure or loss of consciousness or continue insulin administration once reaching moderate hypoglycemia. Nevertheless, the degree of glucose elevation with intranasal was similar to that of the intramuscular and should be more than sufficient for the individual to achieve a glucose level where consciousness is restored and further oral treatment of hypoglycemia can be administered. In the study, glucagon was administered by trained health care professionals under nonemergency conditions; whether similar results can be obtained with either glucagon preparation in an outpatient setting remains to be determined.

In conclusion, this study has demonstrated that intranasal glucagon is effective for the correction of insulin-induced hypoglycemia in adults with type 1 diabetes. Although hypoglycemia was induced in a controlled setting by administering insulin, this should approximate the real-world setting of severe hypoglycemia that occurs owing to excessive therapeutic insulin availability relative to the impaired or absent endogenous glucagon response (10) that normally works to limit hypoglycemia (11). A needle-free intranasal preparation is likely to be preferred due to its relative simplicity compared with injectable formulations, particularly since individuals who must administer rescue glucagon are usually not trained medical professionals. In the current injectable form, administration of glucagon is a relatively complex process and, outside the home, is often unavailable. This leads to suboptimal use of an otherwise effective medication, unnecessary delays in treatment, and costly use of emergency medical systems including ambulance services, emergency room visits, and hospital admissions. Given the results of this study, intranasal glucagon delivery appears promising, and when commercially available, it can be expected to have a substantial beneficial impact on the treatment of severe hypoglycemia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding and Duality of Interest. Funding was provided by a grant from the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust; by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through grants UL1TR000003 (University of Pennsylvania), UL1TR000064 (University of Florida), and UL1TR001108 (Indiana University); and by Locemia Solutions ULC. Studies at the Barbara Davis Center for Childhood Diabetes were performed in their infusion center. Locemia Solutions provided the intranasal glucagon product. M.R.R. has received consultancy payments from Longevity Biotech, Janssen Research & Development, and Semma Therapeutics and research support from Merck. C.A.P. is an employee and member of the board for Locemia Solutions, one of the entities that provided financial support for the conduct of this study. H.D. is an employee for Locemia Solutions. J.L.S.’s nonprofit employer has received grants for support of supplies for investigator-initiated studies from Medtronic. W.V.T.’s nonprofit employer has received consulting fees from Novo Nordisk and Locemia Solutions (Locemia consultancy for protocol development). R.P.W. reports receiving research support from Novo Nordisk and serves as a consultant for Novo Nordisk and Medtronic. E.R. and L.M. received payment for pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic analysis. R.W.B.’s nonprofit employer has received consultant payments on his behalf from Sanofi and Animas and a research grant from Novo Nordisk, with no personal compensation to R.W.B. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author Contributions. M.R.R. and K.J.R. researched data and wrote and edited the manuscript. N.C.F., E.R., and L.M. researched data, performed statistical analysis, and wrote and edited the manuscript. C.A.P., H.D., J.L.S., W.V.T., K.E.B., L.A.D., R.P.W., A.J.A., M.J.H., B.M.N., S.M.M., and R.W.B. researched data and reviewed and edited the manuscript. N.C.F. and R.W.B. are the guarantors of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Clinical trial reg. no. NCT01994746, clinicaltrials.gov.

This article contains Supplementary Data online at http://care.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2337/dc15-1498/-/DC1.

A slide set summarizing this article is available online.

A complete list of participating investigators and coordinators is provided in the Supplementary Data.

References

- 1.Cryer PE. The barrier of hypoglycemia in diabetes. Diabetes 2008;57:3169–3176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brodows RG, Williams C, Amatruda JM. Treatment of insulin reactions in diabetics. JAMA 1984;252:3378–3381 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slama G, Traynard PY, Desplanque N, et al. The search for an optimized treatment of hypoglycemia. Carbohydrates in tablets, solutin, or gel for the correction of insulin reactions. Arch Intern Med 1990;150:589–593 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gold AE, MacLeod KM, Deary IJ, Frier BM. Hypoglycemia-induced cognitive dysfunction in diabetes mellitus: effect of hypoglycemia unawareness. Physiol Behav 1995;58:501–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitmer RA, Karter AJ, Yaffe K, Quesenberry CP Jr, Selby JV. Hypoglycemic episodes and risk of dementia in older patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 2009;301:1565–1572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCoy RG, Van Houten HK, Ziegenfuss JY, Shah ND, Wermers RA, Smith SA. Increased mortality of patients with diabetes reporting severe hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care 2012;35:1897–1901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinstock RS, Xing D, Maahs DM, et al.; T1D Exchange Clinic Network . Severe hypoglycemia and diabetic ketoacidosis in adults with type 1 diabetes: results from the T1D Exchange clinic registry. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:3411–3419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cariou B, Lièvre M, Huet D, Charbonnel B, Sert C, Gouet D. Hypoglycemia among 3048 insulin-treated patients in real life: frequency and predictive factors: results from the prospective DIALOG study. Presented at European Association for the Study of Diabetes (Abstract). Barcelona, Spain, EASD, 2013. Available from http://www.easdvirtualmeeting.org/resources/hypoglycaemia-among-3048-insulin-treated-patients-in-real-life-frequency-and-predictive-factors-results-from-the-prospective-dialog-study--2. Accessed 3 December 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khunti K, Alsifri S, Aronson R, et al. Self-reported hypoglycemia: A global study of 24 countries with 27,585 insulin-treated patients with diabetes: the HAT study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2014;106:S105–S106 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerich JE, Langlois M, Noacco C, Karam JH, Forsham PH. Lack of glucagon response to hypoglycemia in diabetes: evidence for an intrinsic pancreatic alpha cell defect. Science 1973;182:171–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holstein A, Hammer C, Plaschke A, et al. Hormonal counterregulation during severe hypoglycaemia under everyday conditions in patients with type 1 and insulin-treated type 2 diabetes mellitus. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2004;112:429–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrism G, Diment A, Sulway M, Wilkinson M. Glucagon administration - underevaluated and undertaught. Pract Diabetes Int 2001;18:22–25 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pontiroli AE, Alberetto M, Pozza G. Metabolic effects of intranasally administered glucagon: comparison with intramuscular and intravenous injection. Acta Diabetol Lat 1985;22:103–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freychet L, Rizkalla SW, Desplanque N, et al. Effect of intranasal glucagon on blood glucose levels in healthy subjects and hypoglycaemic patients with insulin-dependent diabetes. Lancet 1988;1:1364–1366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pontiroli AE, Calderara A, Pajetta E, Alberetto M, Pozza G. Intranasal glucagon as remedy for hypoglycemia. Studies in healthy subjects and type I diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 1989;12:604–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slama G, Alamowitch C, Desplanque N, Letanoux M, Zirinis P. A new non-invasive method for treating insulin-reaction: intranasal lyophylized glucagon. Diabetologia 1990;33:671–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenfalck AM, Bendtson I, Jørgensen S, Binder C. Nasal glucagon in the treatment of hypoglycaemia in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetic patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1992;17:43–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beck RW, Tamborlane WV, Bergenstal RM, Miller KM, DuBose SN, Hall CA; T1D Exchange Clinic Network . The T1D Exchange clinic registry. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97:4383–4389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Novo Nordisk. GlucaGen prescribing information [Internet]. Available from http://www.novonordiskmedicalinformation.com//file_upload/GlucaGen%20HypoKit%20Prescribing%20Information,April%202014%20.pdf. Accessed 9 September 2015

- 20.Locemia Solutions ULC. Safety and efficacy of a novel glucagon formulation in type 1 diabetic patients following insulin-induced hypoglycemia (AMG102) [Internet]. Available from https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT01556594?term=amg+medical&rank=1. Accessed 23 June 2015

- 21.Hepburn DA, Deary IJ, Frier BM, Patrick AW, Quinn JD, Fisher BM. Symptoms of acute insulin-induced hypoglycemia in humans with and without IDDM. Factor-analysis approach. Diabetes Care 1991;14:949–957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yale JF, Piche C, Lafontaine M, et al. Needlefree nasal delivery of glucagon is superior to injectable delivery in simulated hypoglycaemia rescue. Poster presented at European Association for the Study of Diabetes (Abstract). Stockholm, Sweden, September 2015. Available from http://www.easdvirtualmeeting.org/resources/needle-free-nasal-delivery-of-glucagon-is-superior-to-injectable-delivery-in-simulated-hypoglycaemia-rescue--3. Accessed 3 December 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pacchioni M, Orena C, Panizza P, Cucchi E, Del Maschio A, Pontiroli AE. The hypotonic effect of intranasal and intravenous glucagon in gastrointestinal radiology. Abdom Imaging 1995;20:44–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.