Abstract

The causes of complex diseases are multifactorial and the phenotypes of complex diseases are typically heterogeneous, posting significant challenges for both the experiment design and statistical inference in the study of such diseases. Transcriptome profiling can potentially provide key insights on the pathogenesis of diseases, but the signals from the disease causes and consequences are intertwined, leaving it to speculations what are likely causal. Genome-wide association study on the other hand provides direct evidences on the potential genetic causes of diseases, but it does not provide a comprehensive view of disease pathogenesis, and it has difficulties in detecting the weak signals from individual genes. Here we propose an approach diseaseExPatho that combines transcriptome data, regulome knowledge, and GWAS results if available, for separating the causes and consequences in the disease transcriptome. DiseaseExPatho computationally de-convolutes the expression data into gene expression modules, hierarchically ranks the modules based on regulome using a novel algorithm, and given GWAS data, it directly labels the potential causal gene modules based on their correlations with genome-wide gene-disease associations. Strikingly, we observed that the putative causal modules are not necessarily differentially expressed in disease, while the other modules can show strong differential expression without enrichment of top GWAS variations. On the other hand, we showed that the regulatory network based module ranking prioritized the putative causal modules consistently in 6 diseases, We suggest that the approach is applicable to other common and rare complex diseases to prioritize causal pathways with or without genome-wide association studies.

1. Introduction

Complex diseases result from the interplay of multiple genetic variations and environment factors (1, 2). The putative causal genetic variants can be identified through their associations with disease phenotypes using approaches such as genome wide association study (GWAS) (3). However, the genetic variants do not directly cause disease, but do so by altering cells’ molecular status, as described by epigenomes, transcriptomes, etc., which then escalate to the individual level and manifest as diseases. Hundreds of GWAS studies have been carried out for diverse traits and diseases (3, 4), yet our understanding of most common diseases remains fragmented and uncertain (5). In most cases, knowing the causal genes of diseases is far from knowing the mechanism, limiting our ability to translate the knowledge of disease genetics into prevention and treatment strategies (6, 7).

High-throughput technologies based on sequencing or microarray have enabled genome-wide studies at multiple levels, from GWAS, transcriptome profiling, to meta-genomics (8–11). Integration and joint modeling of the complementary sources of data will enable the most complete view of disease pathogenesis (12–14). Transcriptomic, proteomic, and metagenomic profiling can potentially provide key insights on the pathogenesis of diseases, but the signal from the disease causes and consequences are intertwined (4, 15, 16), making it challenging to extract the causal signals. GWAS and genome sequencing provides direct evidences of genetic cause of diseases, yet variants with small effect size pose great challenges (3, 4).

The gene-regulation network is a graphical summary of the regulation mechanisms of human gene transcriptions. It is composed of the binary relationships among transcription factor – target genes. Despite its simplicity, studies based on the network have revealed important properties of gene regulations (17–20). However there has been limited application of human gene regulatory network in the computational inference of disease causes or mechanisms due to the lack of data (21). With the development of ChIP-seq technology (22, 23) and the coordinated effort such as ENCODE (20, 24) to measure genome wide transcription factor binding profiles, increasingly higher coverage of the human gene regulation network is being achieved.

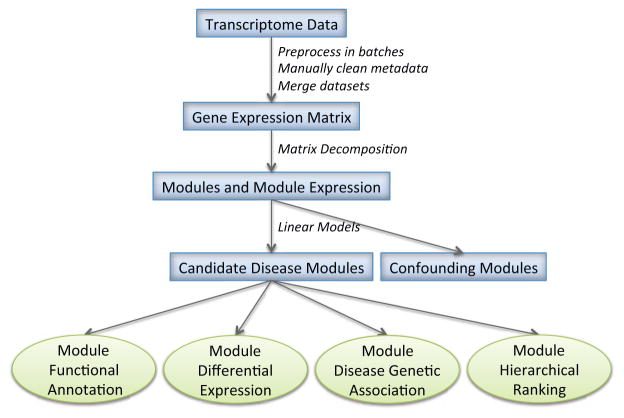

Here we propose a computational pipeline, diseaseExPatho, to infer the molecular mechanism underlying complex human diseases (Figure 1). It takes three types of inputs, transcriptome of a disease of interest, GWAS implicated putative disease causal genes if known, and gene regulation network, which is independent of the specific disease. DiseaseExPatho first computationally decomposes the gene expression data using independent component analysis (ICA) to obtain functional coherent gene modules. It then labels the modules as differentially expressed (DE) and/or putative causal, using a novel statistical inference method for detecting gene enrichment. Finally, it hierarchically ranks the gene modules based on the gene transcriptional regulation network in order to prioritize the putative causal modules even when the disease causal genes are unknown. We applied the method to psychiatric disorders, type II diabetes, and inflammatory bowel diseases, and demonstrated its ability to decompose and prioritize the causal signal in disease transcriptome data with or without the knowledge of putative causal genes.

Figure 1.

Overview of the diseaseExPatho pipeline for causal gene module prioritization

2. Methods

2.1. Transcriptome data

Transcriptome data for psychiatric disorders and diabetes are obtained from GEO(25). Microarray data are preprocessed using the fRMA algorithm(26–29) on batches defined by experiment date. The expression values are summarized to the gene level. For RNA-seqs, the FPKM values are quantile normalized and summarized to the gene level and log2 transformed. Only protein-coding genes are retained. Multiple datasets are merged based on shared gene identifiers and further quantile normalized. Metadata for patients are manually cleaned and standardized.

For the psychiatric disorders, five studies (GEO accessions GSE21935, GSE21138, GSE35974, GSE35977, and GSE25673) are combined. The first four are transcriptomes of brain regions and the last one is a study of iPS cell derived neurons from patients and normal controls. There are 429 samples in total, covering bipolar disorder (BD), schizophrenia (SZ), and major depression (MD). For type II diabetes (T2D), 4 studies (GSE38642, GSE50397, GSE20966, and GSE41762) of pancreatic islets tissues or beta cells are selected. For inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), a single RNA-seq dataset (GSE57945) of pediatric IBD patients is used, total 322 samples.

2.2. Human gene regulation network and disease genetic associations

The gene transcriptional regulation network is computationally extracted from ChIP-seq experiments as well as low throughput studies reported in the literature (see (30) for more details). The dataset is comprised of 146096 direct transcriptional regulation relationships between 384 transcription factors (TFs) and 16967 target genes, and is viewed as a directed graph with edges pointing from TFs to the target genes.

Gene-disease associations from genome wide association studies (GWAS) for psychiatric disorders (bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and major depression), type II diabetes, and inflammatory bowel diseases were retrieved from dbGAP(31), NHGRI(32) and NHLBI(33) catalogs and filtered with loose p-value cutoff 1×10−5 to retain the weak but true disease causing genes. Phenotype terms related to the same diseases are manually examined and putative causal genes are combined. For each SNP, the closest gene or two genes for inter-genic SNP, are retained.

2.3. Independent component analysis for learning gene modules

Independent component analysis (ICA) is an unsupervised machine-learning algorithm for decomposing matrix into underlying simpler and potentially more meaningful component. It is commonly used in signaling processing to decompose mixed and noisy audio signals and estimate the original independent sound sources (34). When applied to transcriptome data, ICA decomposes gene expression into functionally coherent gene modules that correspond to cellular processes or pathways that co-express and co-vary in a biological sample (35). In this study, we decompose transcriptome data from patients in order to achieve mechanistic view of diseases.

Specifically, let matrix Y denotes the expression of G genes in N samples with dimension G×N. ICA approximates a matrix Y as the product of two matrixes Y~S · A, where S is a G×M matrix containing weights of G variables (genes) in the M independent components, while A is a M×N matrix containing the mixing coefficients of the M components in the N samples. It can be viewed as biclustering methods with the two matrixes providing the row and column clustering for original matrix Y. ICA achieves the matrix decomposition through the assumption that the M components in matrix S are statistically independent. We perform ICA using the fastICA algorithm(34, 36, 37) as in previous study(38). The M independent components learned from gene expression data are called gene modules. Each module represents a soft clustering of genes, with the dominant genes having the highest positive or negative weights. Previous study suggest that ICA provide functionally more coherent gene clusters compared to PCA(35). We hence interpret the modules as computationally estimated gene pathways composed of functionally related genes. In addition, we interpret each row of matrix A as the expression of a module in the N samples following previous study(38). For each gene expression matrix, we learn M = 50 gene modules.

2.4. Differential expression of gene modules in disease

For each gene module, we apply linear model of the form to infer the differential expression of the module in diseases versus normal. Note that ai from matrix A is the expression of a module in sample i, is the disease status variables, while is the confounding variables. The significance is accessed by the Wald-T test of βdisease and βconfound being zero. P-values are then corrected by the BH procedure(39) for multiple hypothesis testing, and FDR < 0.05 is viewed significant.

Given the capability of ICA to separate signals resulting from different latent variables, we assume each gene module is associated with one latent variable. This will be true if the number of samples is much larger than the number of latent variables. We therefore label each module by the type of variable that is most strongly associated with it. Specifically, each gene module is marked disease related, if the module expression is significantly associated with the disease status, while less or not significantly associated with confounding variables; or confounding, if the opposite is true. The remaining modules not significant for any of the variables are of uncertain status. Both disease-related or the uncertain modules are retained, while the confounding modules are ignored. For psychiatric disorders and IBD, gender and ages are treated as confounding variables, while for T2D, gender, age and BMI are treated as confounding variables.

2.5. Directed graph based ranking of gene modules

We propose a hierarchical ranking method for gene modules based on gene regulation network. At the high level, we will assign a hierarchical ranking of each gene based on its position in the network, and then for each module, we compute its rank as the weighted average rank of genes in the modules. This approach can be extended to general gene clusters and known gene pathways without loss of generality since an ICA gene module is a weighted gene list, while gene clusters or known gene pathways are special cases of weighted gene lists taking only binary weights.

Given a directed graph and its adjacency matrix M = (mij|mij ∈ {0,1} for i,j = 1 … n), we define a non-negative rank measure r = (ri|i = 1 … n) that is associated with nodes in the graph. We require that the rank of node j to equal (or be the best least square approximation of) the average of the ranks of all parent nodes plus 1, with 1 representing one layer downstream, i.e.,

When the network is rooted, the rank measure can be interpreted the average distance from the root of the network to node j. Written in matrix format, the above problems are formally solved by rT = (1 · M′) · (I − M′)†, where M′ is the in-degree normalized adjacency matrix, 1 is a row vector of n 1s, and † is the pseudo-inverse. However, computing (I − M′)† directly can be intractable for large network. Alternatively, when I − M′ is invertible, we can numerically compute rT iteratively through rT ← (1 + rT) · M′ until convergence. For human gene regulation network, we found that I − M′ is invertible when we removed the self-loops. In this study, we removed the self-loops and used the iterative algorithm for computational efficiency.

Based on the gene ranks, we then calculate the ranks of gene modules. For an ICA module sm = (sgm|g = 1 … G), normalized s.t. Σg sgm2 = 1, the module’s rank is calculated as . Only genes in the regulatory network are included in this calculation.

2.6. Inference of gene modules’ association with genetic causes

We propose a novel algorithm to associate a set of GWAS implicated putative causal genes with a gene module. Specifically, for each module m we built a linear model,

where sgm is the weight of gene g in module m, xg ∈ {0,1} indicates if gene g is a putative causal gene of a disease according to GWAS association p-value < 10−5. When βm is significantly greater than 0, the causal genes are significantly contributing to the gene module, thus module m is considered a putative causal module. Notice that since extreme positive or negative values are equally important for a gene module, we use absolute values |sgm|. Hence, we name the approach bidirectional linear model (biLM).

We also note that due to the nature of this problem, xg is binary, and the method is equivalent to performing a special T-test on the data, thus it can be called bidirectional T-test (biT-test). We use the same approach to detect the association of putative causal genes with the differential expression of genes in disease versus control, by replacing |sgm| with centered differential gene expression , where yg is the differential expression of gene g.

3. Results

We apply diseaseExPatho to three major types of adult psychiatric disorders, schizophrenia (SZ), bipolar disorder (BD) and major depression (MD), as well as type II diabetes (T2D) and inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). The three psychiatric disorders together affect over 10% of the US population. They are widely studied with both transcriptome and GWAS approaches, allowing us to evaluate our method. We compiled transcriptome data from 5 studies of brain tissues and neuron cells. In total, there are 429 samples, including 82 BD, 27 MD, and 160 SZ patients, and 160 normal controls. For T2D we combine transcriptomic data of pancreatic islet from four studies, totally 199 samples, including 50 T2D patients and 149 normal controls. IBD data come from 1 study, total 322 samples, including 218 CD disease, 62 UC, and 42 normal controls. The putative causal genes for the disorders are manually compiled from databases of GWAS associations(31–33), with totally 151, 306, 87, 485, 71, and 229 putative causal genes for BD, MD, SZ, T2D, CD, and UC respectively.

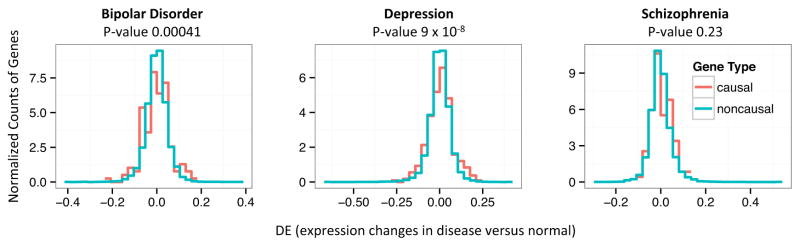

3.1. Genetic causes of diseases leave detectable signals in the transcriptome

Despite the popularity of both GWAS and transcriptomic approach for disease study, there has been limited research on the consistency between GWAS and transcriptome approaches. A recent study reported the gene expression outliers are enriched with rare genetic variations in SZ patients(40). Here we examine the enrichment of GWAS-implicated putative causal genes of 6 diseases in the two tails of gene differential expression profiles. Statistically significant enrichment is detected for both the BD (p-value 0.00024, biLM) and MD (p-value 9.0 × 10−8), but not SZ (p-value 0.23, see Figure 2). Enrichment is also observed for putative causal genes of T2D (p-value 4.3 × 10−8), and CD (p-value 0.032), but not significant for UC (p-value 0.13).

Figure 2.

Overlay of the distributions (normalized counts) for differential expression (DE) of the putative causal genes (red) against DE of the other genes (cyan) in three types of psychiatric disorders. The p-values are obtained by bidirectional linear model comparing the spreads of the DE values.

3.2. Matrix decomposition separates the causal and differentially expressed gene modules

Diseases are generally complex processes. For complex diseases, multiple genetic and environmental factors together contribute to the disease risks. We believe for complex diseases, the causal factors, regardless of the type, cause disease through common molecular pathways of multiple genes. When we apply ICA to patient transcriptome, we expect some of the learnt gene modules to capture the underlying causal molecular pathways, driven by the same underlying causal factor (or a set of closely related causal factors) of the disease. The remaining modules can be downstream in disease pathogenesis or related to (possibly unknown) confounding factors.

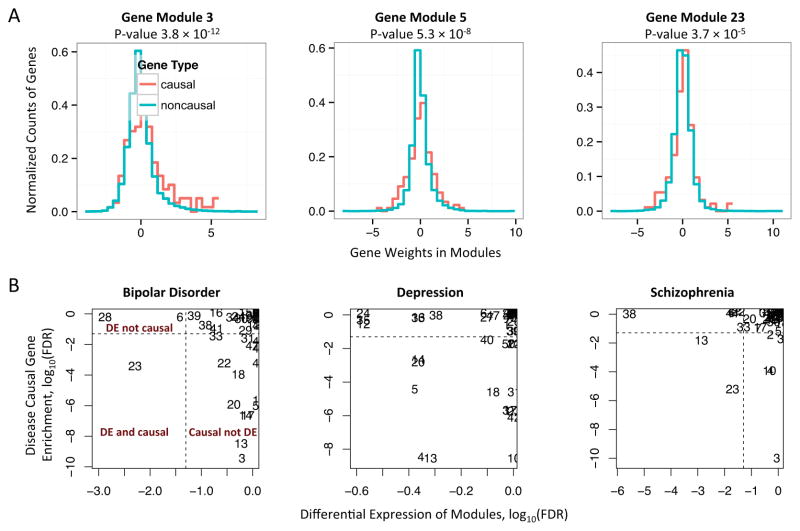

We applied ICA and bidirectional linear model to psychiatric disorders and identified 17, 16, and 8 putative causal gene modules for BD, MD, and SZ. We refer to these significant modules the putative causal modules. We observed that many of the gene modules show a stronger enrichment of putative disease causal genes (Figure 3A) compared to the overall differential expression profiles (Figure 2) in terms of the association p-values. For example, 11, 6, and 8 of the putative causal modules have stronger enrichment p-values than the original differential expression profiles.

Figure 3.

Disease causing and differential expression (DE) are orthogonal at the pathway level. A. Gene modules learnt by ICA and GWAS implicated putative disease causing genes are associated by enrichment analysis. The plots overlay the distributions of the weights of the putative causal genes of bipolar disorder (red) against the distribution of the weights of the other genes (cyan) in 3 modules. The p-values are obtained by biLM comparing the spreads of the genes’ weights in two distributions. B. Scatter plot of the causal gene modules versus the DE gene modules for 3 psychiatric disorders. Many causal gene modules are not significantly differentially expressed, while many DE gene modules are not enriched with putative causal genes. The numbers in the plots are the IDs of gene modules. The x and y axes are FDR (the multi-testing corrected p-values) at log scale. Dashed lines correspond to FDR level 0.05.

Since the modules are derived based on gene expression data, it is important to examine if the putative causal modules are always differentially expressed (DE) in disease versus normal individuals. We calculate each module’s DE as described in method section using a linear regression by removing the effects of confounding factors and correcting the p-values for multi-hypothesis testing. We then use the log of corrected p-value, FDR value here, to indicate the extent of DE. The extent of module’s disease causing effect is calculated using bidirectional linear model. Surprisingly, we observed that majority of the putative causal gene modules are not differentially expressed for the psychiatric disorders (Figure 3B), and similar results are observed on separate analysis of type II diabetes and inflammatory bowel diseases (CD and UC). For example, module 3 is associated with putative causal genes for all 3 psychiatric disorders, but it is not differentially expressed for any of them. This however is consistent with the improved causal gene enrichment at the module level compare to the differential gene expressions, since many disease causal genes are apparently not associated with strong differential expression. In addition, we observed modules (e.g., module 38) that are only differentially expressed but not enriched with putative disease causing genes. Despite this, some putative causal modules are indeed differentially expressed (e.g. module 23, see table 1 for details on selected modules). Overall, we identified 3 and 9 DE gene modules for bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, while 1 and 2 of them are overlapping with the putative causal modules. No DE modules are identified for major depression.

Table 1.

Function annotations of putative causal and differentially expressed modules for the psychiatric disorders. The top 5 putative causal modules (first 5 rows) and top 5 differentially expressed modules (marked DE) are included. Five highest-weighted genes are listed for each module, and those genetically associated with psychiatric disorder are underlined.

| ID | Module Function % | Top 5 Genes | Type | Differential Expression P-value | Enrichment of Putative Causal Genes, P-value | Module Ranking | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP$ | MD$ | SZ$ | BP$ | MD$ | SZ$ | |||||

| 3 | neuronal system; synaptic transmission; gated channel activity | SPHKAP, GABRA6, NEUROD1, CADPS2, CNTN6 | Causal | 0.23 | 0.42 | 0.49 | 4.E-12 | 2.E-07 | 1.E-12 | 34 |

| 13 | axon guidance; nervous system development; glutamate receptor activity | DLK1, ZIC1, PTN, GNAL, DNER | Causal & DE | 0.14 | 0.13 | 3.E-05 | 7.E-11 | 8.E-11 | 8.E-04 | 33 |

| 10 | neuronal system; nervous system development; glutamate receptor activity | PMP2, SLC22A3, SLC17A8, KAL1, CHL1 | Causal | 0.90 | 0.72 | 0.09 | 2.E-07 | 7.E-11 | 5.E-06 | 42 |

| 4 | neuronal system; nervous system development; voltage gated cation channel activity | RGS4, TESPA1, GDA, HTR2A, CDH9 | Causal | 0.61 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 7.E-04 | 2.E-10 | 4.E-06 | 41 |

| 23 | GPCR downstream signaling; transmission of nerve impulse; receptor activity | RELN, MET, PENK, CALB1, GCNT4 | Causal & DE | 2.E-04 | 0.83 | 8.E-04 | 4.E-05 | 1.E-07 | 1.E-07 | 37 |

| 38 | HIF1 TF pathway; signal transduction; drug binding | FKBP5, SLC14A1, PDK4, IL1RL1, ZBTB16 | DE | 9.E-03 | 0.14 | 3.E-08 | 0.05 | 0.35 | 0.26 | 13 |

| 6 | oxidative phosphorylation; carbohydrate metabolic process; oxidoreductase activity | GSTT1, LAPTM4B, ATP6AP1, ATP6V0B, PITHD1 | DE | 2.E-03 | 0.25 | 1.E-03 | 0.21 | 0.62 | 0.43 | 7 |

| 28 | cell cycle; cell cycle process; taste receptor activity | PI15, DLEU1, MSTN, FKBP14, SYCP2L | DE | 2.E-05 | 0.79 | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.87 | 0.66 | 4 |

For each module, three functional terms are provided. They are the most significant terms in canonical pathways, gene ontology (GO) biological process, and GO molecular functions.

BP: bipolar disorder; MD: major depression; SZ: schizophrenia.

3.3. Putative causal modules are ranked lower in the gene regulatory network

GWAS studies are not available for all complex diseases. Given the large sample size requirement, some complex diseases may not have enough population to enable GWAS. We hence examine the possibility to infer putative causal gene modules from expression data directly.

We rank the gene modules based on the directed gene regulation network to prioritize the modules. Multiple studies suggest that essential genes are less likely to be disease causing(23). Our basic assumption is that gene modules ranked top of the network are more essential in the cell, and are less likely to be associated with phenotypically weak variants for complex diseases.

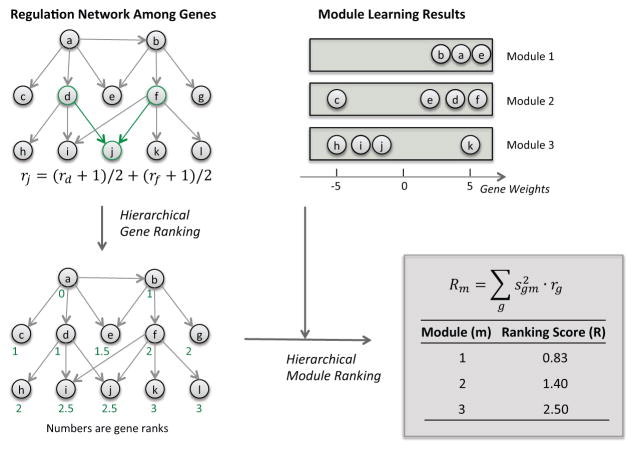

We propose a novel and intuitive rank score for genes based on the regulatory network structure (Figure 4). The key property of the ranking is that a node’s rank is the average of all its parent nodes’ ranks plus 1 (see methods section 2.5 for details). For simple rooted graphs, we show that the resulting rank is the average distance of a node to the root of the graph (Figure 4). It is different from previously proposed gene ranking approaches(17–19) in two major ways. First, it provides an intuitive ranking of nodes that is consistent with topological sort when the graph is acyclic. Second, previous approaches focus on the transcription factors (TFs) and rank from the bottom to the top. Our approach ranks from top to bottom and both TF and non-TFs receive meaningful ranks depending on their locations in the network.

Figure 4.

Directed gene regulation network based ranking of genes (letters a–l) and weighted gene lists (gene modules 1–3). The gene ranking is interpreted as the average distance of a gene to the root of the network when the network is rooted, as the example shown in this figure.

We first examine the ranking of single genes. The putative causal genes are enriched significantly in the bottom half of the network (p-value 0.0007, odd ratio 1.13 for putative causal gene obtained at p-value cutoff 1×10−5)*. Relatedly, GWAS implicated transcription factors also show a weak trend of favoring the bottom half of the network (p-value 0.20), despite that fact that TFs overall have higher ranks (p-value 0.0002, t-test).

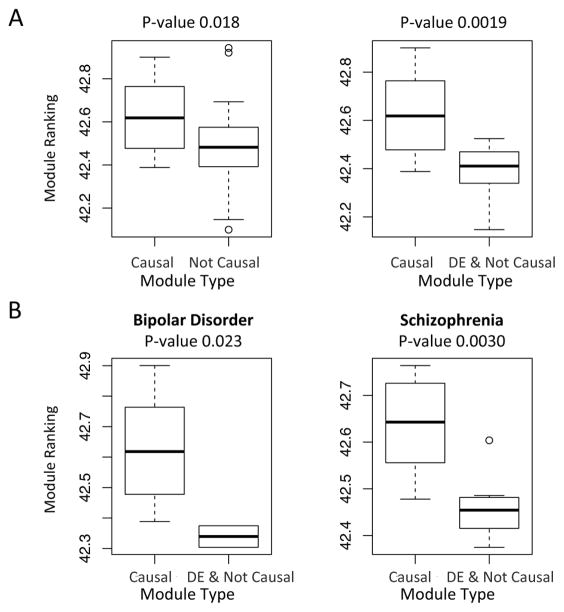

We then examine the module rankings by aggregating the gene rankings based on genes’ weights in the modules (see methods section 2.5). For the psychiatric disorders, we discovered that the putative causal gene modules are ranked significantly lower than the other modules (Figure 5A left, p-value 0.018, two-tailed t-test of ranks compared putative causal and non-causal modules, or p-value 0.028, Spearman rank correlation −0.33 between enrichment p-value and module ranking). Similarly for type II diabetes (p-value 0.16, two-tailed t-test; or p-value 0.0023, Spearman rank correlation −0.43), and inflammatory bowel diseases (p-value 0.019, two-tailed t-test; or p-value 0.00028, Spearman rank correlation −0.50). We further compared the putative causal modules with the differential expressed non-causal modules, and observed significantly lower ranking of the causal modules, this is true for 3 psychiatric disorders together (p-value 0.0019, two-tailed t-test, Figure 5A right), as well as for each psychiatric disorder separately (Figure 5B). This is however not significant for T2D and IBDs.

Figure 5.

Gene regulation network based ranking differentiates the causal versus non-causal gene modules. The causal modules tend to be ranked lower (i.e. with higher rank values). A. Boxplots comparing the ranking of putative causal modules versus other modules (left) or putative causal modules versus the DE & Not Causal modules (right). A putative causal module is defined as a module that shows significant enrichment (FDR < 0.05) of GWAS implicated putative causal genes. A DE & Not Causal module is defined as a differentially expressed module (FDR < 0.05) that is not causal. For each module, p-values for 3 psychiatric disorders are combined into one p-value by Fisher’s methods, for either differential expression or the enrichment of putative causal genes. The p-values shown in the figures are obtained by two-tailed two-sample t-tests. B. The comparison of putative causal modules versus the DE & Not Causal modules for individual psychiatric disorders. Note there are no significant DE modules for major depression.

As a control, we evaluate the ranking on the inverse network (by reversing the TF to target gene regulation directions), to obtain a bottom-up ranking mimicking the approach in previous studies (17–19). None of the results are significant based on the new ranking.

3.4. Biological functions of the gene modules for psychiatric disorders

We annotated the functions of gene modules for psychiatric disorders based on the enrichment of known gene functions curated in the Gene Ontology and canonical pathway databases (41–44). We carefully examined 8 gene modules, covering the top 5 putative causal and the top 5 differentially expressed modules (Table 1). The five putative causal gene modules are annotated with neural related gene functions, such as synaptic transmission and glutamate receptor activity. The three DE and non-causal gene modules are annotated mostly with functions that are not unique to neuronal systems, and are ranked top in gene regulatory network.

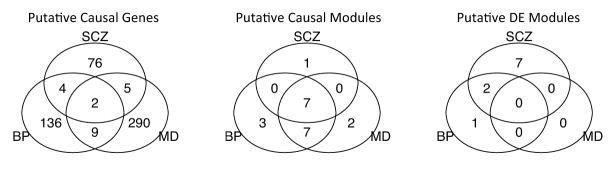

It is worth noting that stronger overlap among the three psychiatric disorders is observed at the module level than the gene level (Figure 6). We believe this is because the gene modules provide additional statistical power than single genes, and the impact of false causal genes from GWAS is minimized at the module level, as the modules are comprised of mainly functional related genes.

Figure 6.

Overlap of putative causal genes, putative causal modules, and DE modules among psychiatric disorders. BP: bipolar disorder; MD: major depression; SCZ: schizophrenia. Significant modules for each disease are identified as those with FDR<0.05 for that disease.

We also examine the functions of the disease-specific putative causal modules. Module 2 is unique to schizophrenia (and weakly for BP). Its top function annotations include GPCR ligand binding, G protein coupled receptor protein signaling pathway, and hormone activity. Module 29 is unique to bipolar disorder. Its top function annotations include 3-UTR mediated translational regulation, translation, and structural constituent of ribosome. Module 33 is unique to bipolar disorder (and weakly to schizophrenia). Its top function annotations include taste transduction, synaptogenesis, and taste receptor activity. Module 47 is unique to bipolar disorder. Its top function annotations include integrin-1 pathway, multicellular organismal development, and actin binding. Module 11 is unique to depression. Its top function annotations include cell adhesion molecules (CAMs), membrane organization and biogenesis, and phosphoric diester hydrolase activity. Module 50 is unique to depression, but it has no significant function annotation.

4. Discussion

Human complex diseases are the consequences of long-term interplay among a suite of abnormal genetic variants and environmental conditions. Previous studies have identified strong organizational patterns of human disease genes from the study of biological networks(23), and it is suggested that human disease genes tend to cluster into modules(45). Various approaches have been developed for predicting gene functions or disease genes using the guilty-by-association rule.

In this study we propose diseaseExPatho that integrates disease transcriptome and human gene regulation network to unravel the pathogenesis pathways in specific diseases. The diseaseExPatho is composed of 4 major components (Figure 1). A) ICA decomposition of gene expression matrix from patients; B) Module differential expression analysis; C) A novel algorithm (biLM) for associating a gene module with GWAS implicated putative causal genes of a disease; D) A novel algorithm for ranking genes and modules based on the gene regulation network.

Especially, we focus on prioritizing the disease causing pathways common to multiple patients by leveraging the gene co-expression pattern as well the hierarchical structure in the gene regulation network. We applied diseaseExPatho to 3 datasets for psychiatric disorders, type II diabetes (T2D) and inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), and obtained consistent and promising results.

4.1. Gene co-expression, differential expression and disease causing

The disease transcriptome data provide two key ingredients of information. First, it provides the genes that are likely active in the disease. This acts as a filter of the gene regulation network to obtain the disease-relevant sub-network. Second, it provides the gene co-expression patterns, which divides the disease-related genes into compact modules with close-related functions.

We use the independent component analysis to simultaneously extract these two types of information, through estimating a set of independent gene expression modules. After labeling the putative causal gene modules based on the enrichment of putative disease causing genes, we observed that majority of the gene modules activated/deactivated in the disease are not associated with causal genetic variations (Figure 3B). In fact, many putative causal modules do not show DE in the patients, while many non-causal gene modules are significantly differentially expressed (Figure 3B and table 1). Such non-causal DE modules may correspond to downstream molecular pathways, or they may be driven by disease-unrelated confounding factors.

With the help of computationally derived gene modules (pathways), we can elevate from the individual causal genes to causal pathways. This provides us with four advantages. First, we have stronger statistical power in detecting the causal mechanisms of diseases, when we aggregate the GWAS signals from the individual gene level to the pathway level. Second, we have a more systematic view of the disease mechanism as revealed by the common functions of multiple genes in a module. Third, we have higher statistical power in detecting gene module’s expression changes compared to gene’s expression changes, as we suffer much less from the multi-hypothesis testing issues, since there are much fewer number of modules than genes. Fourth, the identified gene expression suffers much less from confounding factors, such as patient heterogeneity due to gender and age.

It is a significant and underappreciated fact that the disease causing genes leave significant expression signals in patients’ transcriptome(40). We observed increased expression changes of putative causal genes for psychiatric disorders (Figure 2), as well as T2D and IBDs. This serves as the foundation of transcriptome-based disease etiology inference.

We observed a stronger enrichment of disease causing genes in individual gene modules than using the overall DE profiles (Figure 3A). In the extreme cases of schizophrenia, we observed 8 modules that are significantly enriched with putative schizophrenia causal genes, while no significant enrichment is observed for the differential expression profile in patient versus normal (Figure 2 right). This implies that, first, human disease variations gather in functionally related genes, and second, these functional related genes cluster as co-expression modules in the disease transcriptome, even when the genes do not show strong differential expression in disease.

A weak consistency has been observed between GWAS and gene expression data for prostate cancer (46) and schizophrenia (40). Our findings not only support the consistency, but also provide an explanation of the failure to observe a much stronger consistency. We suggest that many DE signals in expression data are non-causal but rather consequences or driven by confounding factors, as supported by the DE & not causal modules. On the other hand, DE is not a legitimate requirement for all causal genes, as supported by the causal & non-DE modules.

We believe the differential expression approach, although commonly used in transcriptome study, is not the best approach to extract the causal signals in expression data. A recent study observed improved GO term enrichment when selecting SNPs that are associated with gene expression changes(47). We support the integration of expression data and GWAS as a way to remove the noises in GWAS findings. However, given our observations, we believe requiring DE on the causal genes will remove true causal genes. We instead advocate using gene co-expression modules rather than disease differential expression for improved interpretation of GWAS results.

4.2. Causal module prioritization without using known genetic causes

Prior studies suggest that human essential genes (with knock-out lethality in mouse) are less likely to be disease causing (23). We propose a network-based module ranking, and hypothesize that the top-ranked modules are more essential, while the near bottom-ranked modules are more likely to be disease causing. This hypothesis is supported by module ranking results in psychiatric disorders (Figure 5 and table 1), as well as T2D and IBDs. Consistently, GWAS implicated putative disease/phenotype causal genes also prefers the bottom-half of the regulatory network.

To our knowledge, the network we compiled for this study is the largest published network, yet it only covers 384 transcription factors, 25% of the putative 1500 transcription factors in human (48, 49). Despite this, the network already provides meaningful signal for prioritizing the putative causal modules, as is observed in 3 disease datasets. We hence expect improved performance of diseaseExPatho with the accumulation of more and higher quality gene-regulation data.

Although we demonstrate the applications of diseaseExPatho to complex diseases with extensive GWAS results, we suggest the module ranking approach can be applied to prioritize putative causal modules for complex disease that are not well studied by GWAS, such as the idiopathic inflammatory myositis (50, 51).

Acknowledgments

YFL would like to acknowledge the support of TRAM pilot grant for part of this work and Ron Davis for insightful discussions. RBA would like to acknowledge the supported by MH094267, HL117798, LM005652, GM102365 and a grant from Pfizer Inc. We thank Annie Altman-Merino for her assistance with metadata curation of patient samples.

Footnotes

The true causal genes will likely show stronger enrichment, given that a significant portion of the SNP-disease associations are spurious, and two candidate genes are included for intergenic SNPs.

References

- 1.Zondervan KT, Cardon LR. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:89–100. doi: 10.1038/nrg1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marchini J, Donnelly P, Cardon LR. Nat Genet. 2005;37:413–417. doi: 10.1038/ng1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Visscher PM, Brown Ma, McCarthy MI, Yang J. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:7–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCarthy MI, et al. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:356–369. doi: 10.1038/nrg2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rakyan VK, Down Ta, Balding DJ, Beck S. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:529–541. doi: 10.1038/nrg3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bamshad MJ, et al. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:745–755. doi: 10.1038/nrg3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freedman ML, et al. Nat Genet. 2011;43:513–518. doi: 10.1038/ng.840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morozova O, Marra Ma. Genomics. 2008;92:255–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kahvejian A, Quackenbush J, Thompson JF. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1125–1133. doi: 10.1038/nbt1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Z, Gerstein M, Snyder M. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nrg2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heller MJ. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2002;4:129–153. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.4.020702.153438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giallourakis C, Henson C, Reich M, Xie X, Mootha VK. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2005;6:381–406. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.6.080604.162234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacArthur DG, et al. Nature. 2014;508:469–76. doi: 10.1038/nature13127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Auffray C, Chen Z, Hood L. Genome Med. 2009;1:2. doi: 10.1186/gm2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thagard P. Minds Mach. 1998;8:61–78. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Darden L. Mechanism and Causality in Biology and Medicine. 2013;3 http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-94-007-2454-9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhardwaj N, Yan KK, Gerstein MB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:6841–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910867107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu H, Gerstein M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14724–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508637103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yan KK, Fang G, Bhardwaj N, Alexander RP, Gerstein M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:9186–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914771107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerstein MB, et al. Nature. 2012;489:91–100. doi: 10.1038/nature11245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piro RM, Di Cunto F. FEBS J. 2012;279:678–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valouev A, et al. 2008;5:829–834. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barabási AL, Gulbahce N, Loscalzo J. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:56–68. doi: 10.1038/nrg2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernstein BE, et al. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barrett T, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D991–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCall MN, Bolstad BM, Irizarry Ra. Biostatistics. 2010;11:242–53. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxp059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Irizarry RA, et al. Biostatistics. 2003;4:249–64. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCall MN, Jaffee HA, Irizarry RA. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:3153–4. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bolstad BM, Irizarry R, Astrand M, Speed TP. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li YF, Altman RB. Prep. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mailman MD, et al. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1181–6. doi: 10.1038/ng1007-1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Welter D, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:1001–1006. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eicher JD, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;43:D799–D804. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hyvärinen A, Oja E. Neural Networks. 2000;13:411–430. doi: 10.1016/s0893-6080(00)00026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee SI, Batzoglou S. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R76. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-11-r76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hyvärinen A, Oja E. Neural Comput. 1997;9:1483–1492. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hyvarinen A. IEEE Trans Neur Net. 1999;10:626–634. doi: 10.1109/72.761722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Engreitz JM, Daigle BJ, Marshall JJ, Altman RB. J Biomed Inform. 2010;43:932–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. J R Stat Soc Ser B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duan J, et al. Hum Mol Genet. 2015:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ashburner M, et al. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–9. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joshi-Tope G, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D428–32. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kanehisa M. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schaefer CF, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D674–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu X, Jiang R, Zhang MQ, Li S. Mol Syst Biol. 2008;4:189. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gorlov IP, Gallick GE, Gorlova OY, Amos C, Logothetis CJ. PLoS One. 2009;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhong H, Yang X, Kaplan LM, Molony C, Schadt EE. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:581–591. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vaquerizas JM, Kummerfeld SK, Teichmann SA, Luscombe NM. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:252–63. doi: 10.1038/nrg2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kummerfeld SK, Teichmann Sa. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D74–D81. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jani M, et al. Lancet. 2013;381:S56. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gang Q, Bettencourt C, Machado P, Hanna MG, Houlden H. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:88. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-9-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]