ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE:

To examine differences in lung function among sports that are of a similar nature and to determine which anthropometric/demographic characteristics correlate with lung volumes and flows.

METHODS:

This was a cross-sectional study involving elite male athletes (N = 150; mean age, 21 ± 4 years) engaging in one of four different sports, classified according to the type and intensity of exercise involved. All athletes underwent full anthropometric assessment and pulmonary function testing (spirometry).

RESULTS:

Across all age groups and sport types, the elite athletes showed spirometric values that were significantly higher than the reference values. We found that the values for FVC, FEV1, vital capacity, and maximal voluntary ventilation were higher in water polo players than in players of the other sports evaluated (p < 0.001). In addition, PEF was significantly higher in basketball players than in handball players (p < 0.001). Most anthropometric/demographic parameters correlated significantly with the spirometric parameters evaluated. We found that BMI correlated positively with all of the spirometric parameters evaluated (p < 0.001), the strongest of those correlations being between BMI and maximal voluntary ventilation (r = 0.46; p < 0.001). Conversely, the percentage of body fat correlated negatively with all of the spirometric parameters evaluated, correlating most significantly with FEV1 (r = −0.386; p < 0.001).

CONCLUSIONS:

Our results suggest that the type of sport played has a significant impact on the physiological adaptation of the respiratory system. That knowledge is particularly important when athletes present with respiratory symptoms such as dyspnea, cough, and wheezing. Because sports medicine physicians use predicted (reference) values for spirometric parameters, the risk that the severity of restrictive disease or airway obstruction will be underestimated might be greater for athletes.

Keywords: Athletes, Sports, Spirometry, Respiratory function tests

INTRODUCTION

Spirometry is a gold standard pulmonary function test that measures how an individual inhales or exhales volumes of air as a function of time. It is the most important and most frequently performed pulmonary function testing procedure, having become indispensible for the prevention, diagnosis, and evaluation of various respiratory impairments. 1

In Europe, spirometric results are currently interpreted in accordance with the guidelines established by the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), which provide the normal-range reference values for the general population. 2 Among the known determinants of lung function, the duration, type, and intensity of exercise have been shown to affect lung development and volumes. 3 - 5 In addition, athletes can be distinguished from members of the general population in that, in general, the former show better cardiovascular function, larger stroke volume, and greater maximal cardiac output. 4 , 5 Bearing all of this in mind, we can assume that athletes would present with higher spirometric values in comparison with the general population. However, there have been only a few studies addressing the effect of physical activity on pulmonary function test results and investigating the association between body composition and respiratory parameters in athletes. 6 - 8 This takes on greater importance when we consider the fact that there is also a lack of studies dealing with spirometric measures specific to athletes, which could lead to the misclassification or misdiagnosis of certain respiratory dysfunctions. Furthermore, it is possible that highly trained athletes develop maladaptive changes in the respiratory system-such as intrathoracic and extrathoracic obstruction; expiratory flow limitation; respiratory muscle fatigue; and exercise-induced hypoxemia-that can influence their performance. 9 Moreover, some studies have reported positive adaptive changes in lung function in comparison with sedentary individuals, 7 , 10 whereas other studies have reported no such changes. 11 From a theoretical point of view, the differences among the various types of sports could explain this lack of uniformity across studies. Nevertheless, whether regular physical activity increases lung function in elite athletes remains an open question.

The objective of this study was twofold. One aim was to examine differences in lung function among sports that are of a similar nature, according to the type and intensity of exercise performed. An additional aim was to investigate which anthropometric/demographic characteristics correlate with lung volumes and flows. 12

METHODS

This was a cross-sectional study involving 150 male athletes (mean age, 20.9 ± 3.5 years) from four different sports (basketball, handball, soccer, and water polo). The inclusion criteria were playing a sport at the national or international level and engaging in that sport for ≥ 15 h per week. The inclusion criteria were playing a sport at the national or international level and engaging in that sport for ≥ 15 h per week. The exclusion criteria were being a smoker or former smoker, using any medication at the time of testing, and having any disease. The results of the pre-enrollment medical examination indicated that all of the subjects were in good health. Within the last three weeks, none of the subjects had taken any medications on a regular basis; had undergone surgery for cardiac, respiratory, allergic, eye, or ear problems; had had a respiratory infection; had had uncontrolled blood pressure; or had undergone thoracic surgery. In addition, none had a history of pulmonary embolism, active hemoptysis, or unstable angina. We grouped the sports according to the type and intensity of exercise involved, classifying each as involving either static (isometric) or dynamic (isotonic) exercise, 12 and all of the sports evaluated belonged to the highly dynamic group. All participants were informed of the possible risks of participating in the study, and all gave written informed consent. All procedures were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Belgrade School of Medicine, in the city of Belgrade, Serbia, and were conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki for medical research involving human subjects.

Anthropometric parameters

Athletes reported to the laboratory after fasting and refraining from exercise for at least 3 h. Without shoes and wearing minimal clothing, each athlete underwent anthropometric assessments, including the determination of weight and percentage of body fat (BF%), which were measured, respectively, with a scale (to the nearest 0.01 kg) and with a segmental body composition analyzer (BC-418; Tanita, Arlington Heights, IL, USA). Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm with a portable stadiometer (Seca 214; Seca Corporation, Hanover, MD, USA), according to standardized procedures described elsewhere. 13 The BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (kg/m2).

Spirometry

Spirometry was performed following the recommendations of the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Task Force. 10 , 14 Predicted (reference) values for gender, age, and height were in accordance with the ECSC standards. Subjects were instructed not to smoke, exercise, consume alcohol, drink caffeinated beverages, take theophylline, or use β-agonist inhalers prior to the spirometry tests. The testing took place in a laboratory setting, and all tests were performed at the same time of day (between 8:00 and 9:30 a.m.), with the same instruments and techniques. Measurements were carried out under standard environmental conditions: at a comfortable temperature (18-22°C); at an atmospheric pressure of 760 mmHg; and at a relative humidity of 30-60%. The temperature, humidity, and atmospheric pressure in the laboratory were continuously monitored.

Spirometry was performed using a Pony FX spirometer (Cosmed, Rome, Italy). At least three acceptable maneuvers were required for each subject, and the best of the three values was recorded. The highest values for FVC and FEV1 were taken independently from the three curves.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are expressed as mean ? standard deviation. Categorical data are expressed as frequencies. To assess differences between athletes according to the type of sport in which they engaged, we used ANOVA, with multiple post hoc Bonferroni tests. Pearson's correlation coefficient was used in order to test the relationships between anthropometric/demographic and spirometric characteristics. Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All tests were two-tailed, and p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The demographic and anthropometric characteristics of the athletes are shown in Table 1. All investigated parameters differed among the four sports. In comparison with the other athletes, basketball players had significantly higher heights and weights (p < 0.001), although they also showed the lowest BF%. Water polo players had the highest BMI, whereas handball players had the highest BF% (p < 0.001 for both). The difference in BF% was statistically significant in the comparison between handball players and water polo players (p < 0.001).

Table 1. Demographic and anthropometric characteristics of the elite athletes evaluated, by sport played.a .

| Variable | Basketball | Handball | Soccer | Water polo |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 48) | (n = 42) | (n = 35) | (n = 25) | |

| Age, years | 20 ? 2 | 22 ? 4 | 23 ? 4 | 19 ? 1 |

| Height, cm | 200.1 ? 7.1*,† | 180.7 ? 9.4* | 183.5 ? 7.1‡,* | 191.0 ? 4.3 |

| Weight, kg | 91.7 ? 10.1† | 76.1 ? 12.3* | 78.7 ? 7.6‡,* | 90.0 ? 9.8 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.75 ? 1.86* | 23.15 ? 1.88* | 23.31 ? 1.27 | 24.67 ? 2.65 |

| BF% | 8.3 ? 1.0*,† | 13.9 ? 3.5* | 9.5 ? 2.0† | 11.5 ? 2.9 |

BF%: percentage of body fat. aData are expressed as mean ? SD. *p < 0.01 vs. water polo. p < 0.01 vs. handball. ‡p < 0.01 vs. basketball.

The measured spirometric values for the athletes in all four groups are shown in Table 2. The FVC, FEV1, vital capacity (VC), and maximal voluntary ventilation (MVV) values were higher for water polo players than for athletes in the other groups (p < 0.001 for all). In addition, PEF values were significantly higher in basketball players than in handball players (p < 0.001). The differences among the sports in relation to the measured values were not significant for any of the other spirometric parameters evaluated (p > 0.05).

Table 2. Measured spirometric values for the elite athletes evaluated, by sport played.a .

| Variable | Basketball | Handball | Soccer | Water polo |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=48) | (n=42) | (n=35) | (n=25) | |

| FVC (L) | 5.7 ? 0.9*,†,‡ | 6.5 ? 1.3†,‡ | 4.9 ? 1.04‡ | 6.7 ? 0.8 |

| FEV1 (L) | 4.9 ? 0.8*,‡ | 4.4 ? 0.9† | 4.4 ? 0.8‡ | 5.5 ? 0.7 |

| PEF (L) | 10.3 ? 2.5 | 11.1 ? 2.3† | 9.4 ? 2.3 | 10.4 ? 0.8 |

| VC (L) | 5.8 ? 0.9*,‡ | 6.4 ? 1.1† | 5.2 ? 1.0‡ | 6.8 ? 0.8 |

| FEV1/FVC | 84.9 ? 8.3 | 85.2 ? 8.0 | 84.6 ? 7.2 | 82.0 ? 7.5 |

| MVV (L) | 172.5 ? 42.7 | 177.7 ? 44.5 | 161.7 ? 38.6‡ | 200.7 ? 34.6 |

VC: vital capacity; and MVV: maximal voluntary ventilation. aData are expressed as mean ? SD. *p < 0.01 vs. basketball. †p < 0.01 vs. handball. ‡p < 0.01 vs. water polo.

The percentages of predicted values for the spirometric parameters evaluated are shown in Table 3. The FVC, VC, and MVV percentage of predicted values were higher for water polo players than for athletes in the other groups (p < 0.001 for all). In addition, the percentage of predicted FEV1 was significantly higher in water polo players than in basketball players (p < 0.001). The differences among the sports in relation to the percentage of predicted values were not significant for any of the other spirometric parameters evaluated (p > 0.05 for all).

Table 3. Percentage of predicted spirometric values for the elite athletes evaluated, by sport played.a .

| Variable | Basketball | Handball | Soccer | Water polo |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 48) | (n = 42) | (n = 35) | (n = 25) | |

| FVC (%) | 102.4 ? 11.7* | 98.2 ? 20.0* | 100.9 ? 11.2* | 111.8 ? 16.4 |

| FEV1 (%) | 104.1 ? 14.4 | 98.1 ? 18.4* | 103.7 ? 11.5 | 113.4 ? 15.9 |

| PEF (%) | 101.1 ? 22.7 | 106.2 ? 21.0 | 104.8 ? 16.4 | 104.5 ? 21.0 |

| VC (%) | 99.5 ? 11.5* | 94.7 ? 14.8* | 102.6 ? 11.2* | 114.8 ? 16.5 |

| FEV1/FVC | 101.5 ? 9.5 | 101.3 ? 9.8 | 100.4 ? 7.9 | 97.8 ? 8.9 |

| MVV(%) | 108.3 ? 26.7* | 104.5 ? 31.7* | 111.6 ? 17.6* | 143.0 ? 17.4 |

VC: vital capacity; and MVV: maximal voluntary ventilation. aData are expressed as mean ? SD. * p < 0.01 vs. water polo.

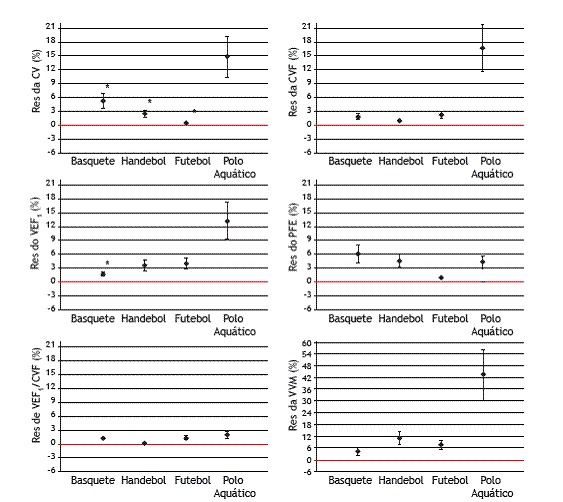

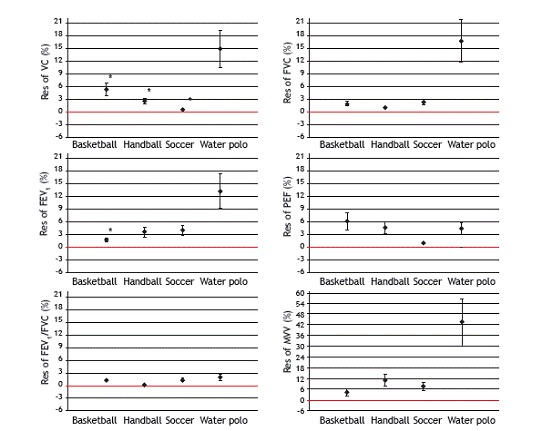

Figure 1 shows the mean values of the residuals (observed minus predicted values) for age-predicted respiratory parameters in all four groups. Not only were the measured values of VC, FVC, FEV1, and MVV significantly higher for water polo players than for athletes in the other groups, but the residuals for those parameters were also significantly different among the various sports (p < 0.001). The residuals for MVV and VC were highest in water polo players, whereas they were lowest in basketball and soccer players, respectively. In addition, there was a statistically significant difference between the highest and lowest residuals for FEV1, which were observed in water polo players and basketball players, respectively (p < 0.001).

Figure 1. Mean ? SD of the residuals (observed minus predicted values) for age-predicted respiratory parameters in the elite athletes evaluated, by sport played. Res: residual; VC: vital capacity; and MVV: maximal voluntary ventilation. *p < 0.05 vs. water polo.

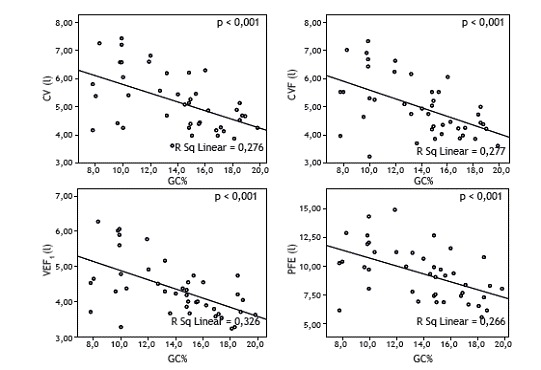

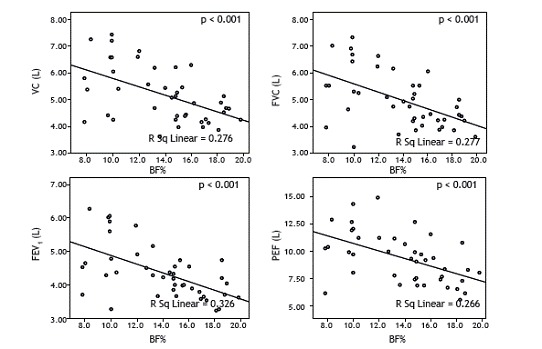

The results of the collective (overall) correlation analysis of anthropometric/demographic and spirometric parameters are presented in Table 4. Most of the anthropometric/demographic parameters correlated significantly with the spirometric parameters evaluated. We found that FVC correlated positively with weight, height, and BMI, the strongest of those correlations being between FVC and weight (r = 0.741; p < 0.001). We also found that FEV1 correlated positively with all anthropometric/demographic parameters except age and BF%, although none of those positive correlations were statistically significant (p > 0.05 for all). In addition, BMI correlated positively with all spirometric parameters (p < 0.001), the strongest positive correlation being between BMI and MVV (r = 0.46; p < 0.001). In contrast, BF% correlated negatively with all spirometric parameters, the strongest negative correlation being between BF% and FEV1 (r = −0.386; p < 0.001).

Table 4. Overall correlation analysis for the sample of elite athletes, as a whole (N = 150).

| FVC (L) | FEV1 (L) | PEF (L) | VC (L) | FEV1/FVC | MVV (L) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.019 | −0.540 | 0.114 | 0.020 | −0.156 | 0.100 |

| Height (cm) | 0.652† | 0.619† | 0.456† | 0.657† | −0.127 | 0.275† |

| Weight (kg) | 0.741† | 0.675† | 0.548† | 0.765† | −0.235† | 0.496† |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.396† | 0.307† | 0.313† | 0.428† | −0.263† | 0.460† |

| BF% | −0.372† | −0.386† | −0.274† | −0.344† | −0.061 | −0.176* |

BF%: percentage of body fat; VC: vital capacity; and MVV: maximal voluntary ventilation. *Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed). †Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

When we looked at within-group correlations, we found that they were similar to those observed in the overall analysis shown in Table 4, except for the water polo group, in which only MVV correlated significantly with weight and BMI (r = 0.503 and r = 0.424, respectively; p < 0.05 for both). In the basketball group, most of the anthropometric/demographic parameters correlated with all of the spirometric parameters, the most significant positive correlations being between age and FVC (r = 0.618; p < 0.001) and between height and VC (r = 0.649; p < 0.001). In the soccer group, height, weight, and BMI all correlated positively with FVC and VC (p < 0.001 for all), the strongest such correlation being between weight and VC (r = 0.76; p < 0.001). We found that BF% did not correlate significantly with any of spirometric parameters evaluated (p > 0.05 for all). In the handball group, the most significant correlations were those that FVC and VC presented with all of the anthropometric/demographic parameters evaluated (p < 0.001 for all).

As can be seen in Figure 2, all of the abovementioned correlations were positive, except for those that BF% presented with all of the spirometric parameters evaluated. As in the overall correlation analysis, the most significant negative correlation was that between BF% and FEV1 (r = −0.326; p < 0.001).

Figure 2. Correlations between percentage of body fat (BF%) and spirometric parameters, in handball players. VC: vital capacity.

DISCUSSION

It is generally accepted that elite athletes and physically active individuals tend to have higher cardiorespiratory fitness levels. In the present study, the measured values were significantly higher than the predicted values for most of the spirometric parameters in all four groups of athletes. This finding could be of great importance in the diagnosis of respiratory disorders, especially in cases of airway obstruction. 1

Our results are in agreement with those reported in other studies. 15 , 16 In a cross-sectional study conducted by Myrianthefs et al., which included 276 athletes engaged in various sports, the results were similar to those obtained in our study. 1 Those authors reported not only that the measured values for spirometric parameters were higher in the athletes than in the general population but also that those values were highest among the athletes who engaged in water-based sports. That leads us to one of the most striking results of our study-the fact that the values for spirometric parameters were highest among the athletes who engaged in water polo, which is a representative water-based sport, than among those who engaged in other sports involving the same type and intensity of exercise. Another major finding of the present study was that, in addition to the fact that the values for spirometric parameters were higher among the athletes who engaged in water polo than among those who engaged in land-based sports, the ECSC prediction equations underestimated certain spirometric values in the elite athletes, as has previously been reported. 17 , 18 This finding is in accordance with those of other studies showing that water polo players present statistically higher values for the major spirometric parameters (FVC, FEV1, VC, and MVV), suggesting that swimming on a regular basis improves lung function. 7 , 19

In the present study, the athletes who engaged in land-based sports showed relatively "normal" spirometric values in relation to age- and height-predicted values, whereas water polo players showed FEV1 values approximately 16% higher than the predicted values. Although this is well known, the question remains: is the superior lung volume in athletes who engage in water-based sports a consequence of their training, or is it (to some extent or completely) due to natural endowment? In addition, although we found the values of FEV1 and FVC to be higher in the water polo players than in the other athletes, the FEV1/FVC ratio was lower in the former group. This suggests that lung efficiency was higher in the other athletes, or that the water polo players had more residual capacity. 13 There are various explanations for why water polo players and athletes who engage in other water-based sports generally have higher lung volumes than do athletes who engage in land-based sports. Swimmers not only tend to have characteristic skeletal features at an early age but also tend to be tall and thin, as well having a high biacromial diameter for their age. Furthermore, some studies have shown that swimming on a regular basis alters the elasticity of the lungs and of the chest wall, which leads to further improvement in the lung function of swimmers and of athletes who engage in other water-based sports. 7 , 20 Moreover, the fundamental nature of the exercise engaged in by water polo players is, in some aspects, diametrically different from that of the exercise engaged in by athletes who play land-based sports. During immersion, the water pressure increases the load on the chest wall, thus elevating airway resistance. The ventilatory restriction that occurs momentarily in every respiratory cycle leads to intermittent hypoxia, which triggers an increase in the respiratory rate. 1 Overall, athletes who engage in water-based sports tend to have functionally better respiratory muscles as a result of the greater pressure they are subjected to during immersion in the water. 7 , 20 , 21 Last but not least, it has been demonstrated that genetic factors make a substantial contribution to the enhanced lung function in swimmers. 22

In addition to the significant differences between athletes who play water-based sports and those who play land-based sports, in terms of the spirometric values observed and confirmed in this study, another noteworthy aspect of our results is the obvious distinction among the three land-based sports evaluated. To our knowledge, there have been no studies investigating such differences, which makes our study even more important. One possible explanation is that every sport differs in terms of the type and intensity of the exercise involved, which varies by season, as well as that there are sport-specific adaptations of body composition, a phenomenon known as "sport-specific morphological optimization". 23

The results of our overall correlation analysis showed that almost all of the anthropometric/demographic parameters correlated significantly with the spirometric parameters evaluated. We found that FVC correlated positively with weight, height, and BMI, correlating most strongly with weight. In addition, BMI correlated positively with all spirometric parameters, the strongest positive correlation being between BMI and MVV. However, BF% correlated negatively with all spirometric parameters, correlating most strongly with FEV1. In our analysis of within-group differences, we found that the correlations were similar to those observed in the overall analysis, except for the water polo players, among whom MVV correlated significantly with weight and BMI. Our results showed that some anthropometric parameters, especially BF%, correlated negatively with the spirometric parameters evaluated, thereby demonstrating, as in other studies, that an increase in body fat can induce a decrease in lung function. 16 , 24 This finding is in accordance with those of other studies in the literature and can be explained by a reduction in expiratory reserve volume and functional residual capacity as a result of decreased lung compliance, decreased chest wall volume, and increased airway resistance. 24 Our results are in agreement with those of a study involving obese individuals, which demonstrated that lung function, expressed as DLCO, correlates positively with lean body mass, 25 which is the opposite of BF%. In addition, some authors have reported that DLCO correlates positively with BMI, 26 although not with BF%. 27 It is well known that in normal individuals (those engaged in regular physical activity), DLCO can double in proportion to the increased cardiac output, 28 thus potentially explaining the fact that BF% has no influence on the variability of DLCO in elite athletes.

According to the literature, higher levels of fat mass and obesity in general, even in athletes, are significantly associated with less low-frequency heart rate variability, which mainly reflects sympathetic activity. In addition, recent studies have shown that in some pulmonary disorders, even mild disorders, cardiac autonomic modulation is increased when there is sympathetic dominance of the autonomic balance. This is also associated with decreased DLCO, which could explain the negative correlations observed in our study. 29

Perhaps the most important finding of the present study is that water polo players showed higher spirometric values than did the athletes in the other groups, indicating that the lung volumes and capacities of water polo players are mostly affected by the fact that they engage in a water-based sport. However, what is responsible for the high prevalence of asthma among swimmers remains an open question. Nevertheless, although the unique anthropometric characteristics of athletes engaged in water-based sports have, as previously mentioned, been shown to be mostly attributable to genetic endowment, it remains unclear whether the superior lung function found in such athletes is due to genetic influences or to the specific pattern of exercise. 22

We found that measured spirometric values were significantly higher in elite athletes than in the general population, regardless of age or the type of sport played. These results are particularly relevant for cases in which an athlete seeks treatment for respiratory symptoms such as dyspnea, cough, and wheezing. Because sports medicine physicians use predicted (reference) values for spirometric parameters, the risk that the severity of restrictive disease or airway obstruction will be underestimated might be greater for athletes. Nevertheless, although our study included only athletes engaged in sports that were similar in terms of the type and intensity of exercise involved, water polo players stood out for their relatively high spirometric values. Our results suggest that the type of sport has a significant impact on respiratory adaptation. Because of these sport-specific differences, there is a need for further investigations examining specific exercise patterns; the influence of the duration, severity, and intensity of exercise; the early years of training; respiratory muscle strength; and specific genetic influences.

Funding Statement

Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Serbia (N° III41022)

Footnotes

Financial support: This work was supported by the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Serbia (N° III41022).

Study carried out at the Institute of Medical Physiology, Belgrade, Serbia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Myrianthefs P, Grammatopoulou I, Katsoulas T, Baltopoulos G. Spirometry may underestimate airway obstruction in professional Greek athletes. Clin Respir J. 2014;8(2):240–247. doi: 10.1111/crj.12066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ, Baur X, Hall GL, Culver BH. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3-95-yr age range the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J. 2012;40(6):1324–1343. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00080312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Losnegard T, Hallén J. Elite cross-country skiers do not reach their running VO2max during roller ski skating. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2014;54(4):389–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galy O, Ben Zoubir S, Hambli M, Chaouachi A, Hue O, Chamari K. Relationships between heart rate and physiological parameters of performance in top-level water polo players. Biol Sport. 2014;31(1):33–38. doi: 10.5604/20831862.1083277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carrick-Ranson G, Hastings JL, Bhella PS, Fujimoto N, Shibata S, Palmer MD. The effect of lifelong exercise dose on cardiovascular function during exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2014;116(7):736–745. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00342.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Degens H, Rittweger J, Parviainen T, Timonen KL, Suominen H, Heinonen A, Korhonen MT. Diffusion capacity of the lung in young and old endurance athletes. Int J Sports Med. 2013;34(12):1051–1057. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1345137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doherty M, Dimitriou L. Comparison of lung volume in Greek swimmers, land based athletes, and sedentary controls using allometric scaling. Br J Sports Med. 1997;31(4):337–341. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.31.4.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazic S, Lazovic B, Djelic M, Suzic-Lazic J, Djordjevic-Saranovic S, Durmic T. Respiratory parameters in elite athletes--does sport have an influence. Rev Port Pneumol (2006) 2015;21(4):192–197. doi: 10.1016/j.rppnen.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hackett DA, Johnson N, Chow C. Respiratory muscle adaptations a comparison between bodybuilders and endurance athletes. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2013;53(2):139–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacAuley D, McCrum E, Evans A, Stott G, Boreham C, Trinick T. Physical activity, physical fitness and respiratory function--exercise and respiratory function. Ir J Med Sci. 1999;168(2):119–123. doi: 10.1007/BF02946480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biersteker MW, Biersteker PA. Vital capacity in trained and untrained healthy young adults in the Netherlands. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1985;54(1):46–53. doi: 10.1007/BF00426297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell JH, Haskell W, Snell P, Van Camp SP. Task Force 8 classification of sports. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(8):1364–1367. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng YJ, Macera CA, Addy CL, Sy FS, Wieland D, Blair SN. Effects of physical activity on exercise tests and respiratory function. Br J Sports Med. 2003;37(6):521–528. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.37.6.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(2):319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galanis N, Farmakiotis D, Kouraki K, Fachadidou A. Forced expiratory volume in one second and peak expiratory flow rate values in non-professional male tennis players. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2006;46(1):128–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guenette JA, Witt JD, McKenzie DC, Road JD, Sheel AW. Respiratory mechanics during exercise in endurance-trained men and women. J Physiol. 2007;581(3):1309–1322. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.126466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, Crapo RO, Burgos F, Casaburi R. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(5):948–968. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00035205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lazovic B, Mazic S, Suzic-Lazic J, Djelic M, Djordjevic-Saranovic S, Durmic T. Respiratory adaptations in different types of sport. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19(12):2269–2274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armour J, Donnelly PM, Bye PT. The large lungs of elite swimmers an increased alveolar number? Eur Respir J. 1993;6(2):237–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson M, Hopkins W, Roberts A, Pyne D. Ability of test measures to predict competitive performance in elite swimmers. J Sports Sci. 2008;26(2):123–130. doi: 10.1080/02640410701348669. 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lomax ME, McConnell AK. Inspiratory muscle fatigue in swimmers after a single 200 m swim. J Sports Sci. 2003;21(8):659–664. doi: 10.1080/0264041031000101999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fisk MZ, Steigerwald MD, Smoliga JM, Rundell KW. Asthma in swimmers a review of the current literature. Phys Sportsmed. 2010;38(4):28–34. doi: 10.3810/psm.2010.12.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berglund L, Sundgot-Borgen J, Berglund B. Adipositas athletica a group of neglected conditions associated with medical risks. Scand J Med Sci Sports, 2011;21(5):617–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2011.01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paulo R, Petrica J, Martins J. Physical activity and respiratory function corporal composition and spirometric values analysis. Acta Med Port. 2013;26(3):258–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pekkarinen E, Vanninen E, Länsimies E, Kokkarinen J, Timonen KL. Relation between body composition, abdominal obesity, and lung function. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2012;32(2):83–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097X.2011.01064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zavorsky GS, Kim do J, Sylvestre JL, Christou NV. Alveolar-membrane diffusing capacity improves in the morbidly obese after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2008;18(3):256–263. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9294-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li AM, Chan D, Wong E, Yin J, Nelson EA, Fok TF. The effects of obesity on pulmonary function. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88(4):361–363. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.4.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zavorsky GS, Beck KC, Cass LM, Artal R, Wagner PD. Dynamic vs fixed bag filling: impact on cardiac output rebreathing protocol. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2010;171(1):22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim JA, Park YG, Cho KH, Hong MH, Han HC, Choi YS. Heart rate variability and obesity indices emphasis on the response to noise and standing. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18(2):97–103. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.18.2.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]