Abstract

This study examined infants’ sensitivity to a speaker’s verbal accuracy and whether the reliability of the speaker had an effect on their selective trust. Forty-nine 18-month-old infants were exposed to a speaker who either accurately or inaccurately labeled familiar objects. Subsequently, the speaker administered a series of tasks in which infants had an opportunity to: learn a novel word, imitate the speaker’s “irrational” actions, and help the speaker obtain an out-of-reach object. In contrast to infants in the accurate (reliable) condition, those in the inaccurate (unreliable) condition performed more poorly on a word-learning task and were less likely to imitate. All infants demonstrated high rates of instrumental helping behavior. These results are the first to demonstrate that infants as young as 18 months of age cannot only detect a speaker’s verbal inaccuracy but also use this information to attenuate their word recognition and learning of novel actions.

INTRODUCTION

Young infants are impressionable learners, whose main means of acquiring new knowledge is through observation and interaction with another individual (Heyes, 1994). This however can entail taking certain risks, as the information can be misleading or inappropriate. Indeed, not all individuals have accurate or relevant knowledge about a given topic—some tend to make errors, whereas others may intend to deceive. This poses a unique challenge to young children who are dependent on others to learn new and culturally relevant information (Csibra & Gergely, 2009; Gergely & Csibra, 2005, 2006; Gergely, Egyed, & Király, 2007; Jaswal & Neely, 2006). One key strategy implemented by young children in selecting whom to trust and learn from is to consider a model’s epistemic reliability (Harris & Corriveau, 2011; Mascaro & Sperber, 2009; Rendell et al., 2011; Sperber et al., 2010).

There is a growing body of the literature on children’s sensitivity to others’ epistemic reliability demonstrating that by 3–4 years of age, children consider reliability as a characteristic of an individual (Einav & Robinson, 2011; Harris, 2007; Koenig, Clément, & Harris, 2004; Koenig & Harris, 2005; Sabbagh & Baldwin, 2001; Scofield & Behrend, 2008; Sperber et al., 2010). In this research, children have been shown to attend to the nature of the verbal information given by speakers, using their confidence and certainty (Sabbagh & Baldwin, 2001), conventionality (Diesendruck, Carmel, & Markson, 2010), and accuracy in labeling a familiar object (Corriveau & Harris, 2009; Koenig et al., 2004; Scofield & Behrend, 2008), to identify who is a reliable source and consequently guide whom to learn novel words from (Jaswal & Neely, 2006; Koenig & Harris, 2005b; Pasquini, Corriveau, Koenig, & Harris, 2007; Scofield & Behrend, 2008; Sobel & Corriveau, 2010).

A limited body of research examining infants’ sensitivity to the epistemic reliability of others also exists within the domain of language. In particular, infants have been found to be sensitive to others’ linguistic mistakes, with 24-month-olds saying “no” (Pea, 1982), and 16-month-olds looking longer (Koenig & Echols, 2003) at speakers who mislabel familiar objects. Most recently, 24-month-olds have been shown to correctly distinguish between unreliable and reliable speakers when learning a new word, being less able to map a novel label to an object when tested by unreliable, inaccurate speakers (Koenig & Woodward, 2010; Krogh-Jespersen & Echols, 2012). Thus, within the domain of word learning, while infants seem to recognize the accuracy of a person’s word-labeling behavior, toddlers can use this information to determine from whom it is best to learn new words. Given that infants entering their second year of life are rapidly expanding their vocabulary (Gurteen, Horne, & Erjavec, 2011; Reznick & Goldfield, 1992) and possess a fairly large receptive vocabulary by 18 months (e.g., Fenson et al., 1991), their early verbal expertise might render them sensitive to others’ verbal accuracy that in turn might affect their word learning. Thus, the main goal of the current study was to add to the extant literature on the developmental origins of children’s sensitivity to epistemic reliability by being the first to examine whether infants learn new words differently from accurate and inaccurate speakers.

Beyond influencing learning in the domain of language, a source’s verbal reliability has been shown to exert effects on children’s behavior in other closely related domains. Specifically, 3- to 4-year-old preschoolers have been found to prefer to learn new object functions (Koenig & Harris, 2005a) as well as infer object properties and relations (Clément, Koenig, & Harris, 2004; Kim, Kalish, & Harris, 2012) from a source who was more accurate in object labeling. Children at the same age also prefer to imitate the actions of a verbally accurate source within the context of a rule-governed game and believe them to be the norm, consequently making normative protests toward those third parties who do not conform to these actions (Rakoczy, Warneken, & Tomasello, 2009). Importantly, research demonstrating the developmental origin of this effect, specifically whether a model’s verbal accuracy can influence infants’ learning in other domains, has yet to be explored. Thus, another aim of the current study was to determine whether infants would judge a speaker who was verbally accurate to also be a reliable source beyond the domain of language as preschoolers do.

As a culturally normative process that develops around the time of language, the domain of imitation is an area worthy of exploring this effect. Indeed, between the ages of 12 and 18 months, infants understand others’ goals and intentions (e.g., Sodian & Thoermer, 2004; Tomasello, Carpenter, Call, Behne, & Moll, 2005) and can imitate what they infer to be the person’s intended (Carpenter, Akhtar, & Tomasello, 1998; Olineck & Poulin-Dubois, 2005) and rational (Gergely, Bekkering, & Király, 2002; Schwier, Van Maanen, Carpenter, & Tomasello, 2006) goal. In addition, by the age of 14 months, infants become selective imitators on the basis of others’ epistemic reliability, taking into consideration whether a model possesses accurate knowledge about conventional object properties and functions when deciding whether or not to imitate. For example, infants of that age are more likely to imitate a model who demonstrates reliable affective and communicative cues, such as someone who expressed excitement while looking into a box that contains a toy as opposed to someone showing the same affect while looking into an empty box (Poulin-Dubois, Brooker, & Polonia, 2011). At this same age, infants are also more likely to imitate a model that has previously demonstrated appropriate usage of familiar objects, such as putting a shoe on his foot as opposed to his hand (Zmyj, Buttelmann, Carpenter, & Daum, 2010). Thus, the current study aimed to examine whether infants would also be selective imitators on the basis of whether a model demonstrated accurate knowledge about familiar object labels.

In addition, children’s willingness to assign positive “halo” attributes to a model based on his or her past epistemic reliability can be quite broad in scope. For example, 4-year-old children will credit knowledge to an alleged expert beyond his or her domain of expertise, believing an “animal expert” would also know about other novel facts, such as how a carburetor works (Taylor, Esbensen, & Bennett, 1994). Furthermore, children will even attribute positive traits or dispositions to a person who has demonstrated expertise. Specifically, 4-year-olds will believe that a verbally accurate source is “smarter” than someone inaccurate, without concluding that the person is “stronger”, “nicer” or competent in other domains beyond object labeling (Fusaro, Corriveau, & Harris, 2011), whereas 5-year-old children will believe a verbally accurate source is more likely to be prosocial to others than someone who was verbally inaccurate (Brosseau-Liard & Birch, 2010). Infants also make attributions to a person based on prior accuracy or reliability. For example, by 14 months of age, infants are more likely to attribute beliefs (Poulin-Dubois & Chow, 2009) and follow the gaze (Chow, Poulin-Dubois, & Lewis, 2008) of a model whose affective and communicative cues have been accurate and reliable (same reliability manipulation as Poulin-Dubois et al., 2011, described above). What has not been demonstrated is whether infants make global generalizations based on a person’s record of verbal accuracy, as older children do, and believe that an accurate as opposed to an inaccurate source is a more worthy candidate for them to help.

Instrumental helping is an instance of prosocial behavior that develops steadily between the ages of 14 and 18 months, wherein infants use a person’s communicative cues, such as pointing and verbal utterances, to interpret and consequently help fulfill his or her intended but unmet goal (Ross & Lollis, 1987; Warneken & Tomasello, 2006, 2007, 2009). Infants’ helping behavior is also affected by a person’s knowledge state as revealed by one study showing that infants only help a person locate an object if that person was not present when the object’s location was changed (Lizkowski, Carpenter, Striano, & Tomasello, 2006). On the other hand, infants before the age of 18 months appear to be motivated by intrinsic altruistic tendencies in that they will provide help regardless of obstacles, reward, or incentive (Warneken & Tomasello, 2009). Indeed, it has been suggested that infants only gradually learn to direct aid selectively (Hay, 2009; Hay, Caplan, Castle, & Stimson, 1991; Vaish, Carpenter, & Tomasello, 2010), and that by the age of 21 months, can discriminate whom they help on the basis of a person’s benevolent intent (Dunfield & Kuhlmeier, 2010). Thus, the current study also included an instrumental helping task to examine whether a speaker’s verbal inaccuracy would exert a strong enough effect to deter infants’ robust helping behavior.

Building upon recent research exploring the mechanisms that young infants use to guide their selective learning from a single source (Koenig & Woodward, 2010) as opposed to a forced-choice comparison (e.g., Birch, Vauthier, & Bloom, 2008; Corriveau & Harris, 2009; Koenig et al., 2004; Scofield & Behrend, 2008), the current study employed a between-subjects design to compare the rates at which 18-month-old infants would choose to learn a novel word as well as imitate and help an epistemically reliable versus unreliable adult. Inaccurate labels were used for familiar objects in order to test whether infants use their existing verbal knowledge to detect inaccurate labels. It was expected that 18-month-old infants would be able to use their growing vocabulary to track the verbal reliability of a speaker and thus be less willing to learn a novel label from an inaccurate source, as has been previously shown with 24-month-olds (Koenig & Woodward, 2010; Krogh-Jespersen & Echols, 2012). With regard to learning new actions, it was expected that infants would only expect someone who seemed to possess conventional knowledge to produce actions that are efficient and reasonable (e.g., Csibra & Gergely, 2009; Poulin-Dubois et al., 2011; Rakoczy et al., 2009; Zmyj et al., 2010), and thus be less likely to imitate someone previously epistemically unreliable on a rational imitation task. Finally, considering that only older children ascribe broad positive attributes to a person based on his or her verbal accuracy (Brosseau-Liard & Birch, 2010) and that nonepistemic characteristics such as kinship, familiarity, and reciprocity appear to influence older children’s prosocial behavior (Dunfield & Kuhlmeier, 2010; see Warneken & Tomasello, 2009 for a review), it was considered unlikely that young infants would reduce their willingness to help due to a speaker’s verbal inaccuracy.

METHOD

Participants

Forty-nine 18-month-old infants (23 males and 26 females) were tested (M = 18.19, SD = 0.85), ranging from 16.79 to 21.0 months. Reflecting the demographics of the population of the large city from which the sample was recruited, infants’ primary language was either English (n = 35) or French (n = 14). As a noun bias has been reported in infants’ early vocabulary for each of these languages, it was considered appropriate to group them together for the purpose of this study, given that the reliability of the speaker’s knowledge for nouns was manipulated (see Katerelos, Poulin-Dubois, & Oshima-Takane, 2011 for a similar procedure). A native speaker of the target language tested all infants in their mother tongue. All participants were recruited from birth lists provided by a government health agency and were residing in a large Canadian city. They were all born within a normal gestation period and experienced no birth complications. Thirteen additional infants were tested, but were excluded due to fussiness (n = 9) and technical difficulties (n = 4).

Design and procedure

Prior to starting the experiment, infants were familiarized with the testing environment while their parents were asked to complete a demographic questionnaire, a 20-word checklist indicating the words that their child understood, and a French or English version of the short-form MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory—Level II measuring infants’ productive vocabulary (MCDI; Fenson et al., 2000). Productive vocabulary is commonly used in studies examining word-learning ability in similar aged infants (Jaswal & Malone, 2007; Koenig & Woodward, 2010). In addition, increases in infants’ word production have been reported to occur at the same time as increases in their comprehension (e.g., Goldfield & Reznick, 1990). During testing, infants were seated in a highchair across from the experimenter or on their parent’s lap if they were unwilling to sit in the highchair. Parents were instructed to refrain from prompting their child in any way. The reliability task was always administered first, with the remaining tasks counterbalanced in order.

Reliability task

Participants were randomly assigned to either a reliable (n = 24) or an unreliable (n = 25) condition. Four small plastic objects were labeled either correctly or incorrectly, depending on the condition. The list of possible objects to choose from included: a ball, banana, bird, dog, spoon, chair, and shoe. These objects were chosen, as French- and English-speaking infants of this age typically know their name (O’Connell, Poulin-Dubois, Demke, & Guay, 2009). Infants in both conditions knew the label for at least three of the four objects chosen. The experimenter allowed the child to play with an object for a timed period of 15 sec (Phase One). Afterward, the experimenter picked up the object and manipulated it while labeling it three times in an animated manner during a period lasting no longer than 10 sec (Phase Two). Infants in the reliable condition watched the experimenter correctly label the objects while infants in the unreliable condition watched the experimenter incorrectly label the objects. The spoon was always mislabeled a truck, the dog a telephone, the banana a cow, the shoe a bottle, the ball a rabbit, the bird an apple, and the chair a flower. Therefore, for the unreliable condition, infants watched as the experimenter pointed to a bird and said, “That’s an apple. An apple. Look at the apple,” if their parents had indicated that they understood the word bird and thus could recognize that it had been mislabeled. The incorrect labels were made to differ from the correct label in terms of category, first phoneme, and (except in one case) number of syllables. Once the experimenter finished labeling the object, she gave it back to the infant. The infant was then allowed to play with the object for another 15 sec (Phase Three). This sequence was repeated three times, for a total of four trials.

The reliability task was coded for various behaviors during Phase Two and Three. During Phase Two, the proportion of infants’ total looking time at the experimenter while she was labeling the toy (in sec) was computed. In Phase Three, the proportion of looking time at the experimenter, at the toy, and at the parent (in sec) was coded, once the toy was placed in front of the infant. All sessions were recorded and coded by the primary experimenter. An independent observer coded a random selection of 20% (n = 10) of the videotaped sessions to assess interobserver reliability in each condition. Using Pearson’s product-moment correlations, the mean interobserver reliability for looking time variables in the reliability task was r = .93 (range = .85–.97).

Word learning task

This task was adapted from the discrepant condition used by Baldwin (1993). It required that infants disengage their attention from their own toy to focus on the toy that the speaker was labeling. As such, it allowed for a direct comparison of infants’ attentiveness to the speaker’s utterances across conditions. While this procedure is challenging for very young word learners, infants at 18 months of age have been found to successfully disengage and learn novel words (Baldwin, 1993; O’Connell et al., 2009). The procedure included three phases: a warm-up phase, a training phase, and a test phase. The test phase consisted of both familiar and novel word comprehension trials. Based on infants’ knowledge of the names of familiar objects (indicated on the word comprehension checklist), two object pairs not previously used in the reliability task were chosen: one pair was used exclusively for the warm-up phase and the other pair exclusively for the test phase, during the familiarization trials. The objects were (as much as possible) similar in terms of size and attractiveness, but differed in terms of category and appearance.

Warm-up phase

During the warm-up phase, the experimenter presented the infant with a box containing a pair of familiar objects and asked for one of them to encourage the infant to give her the requested object. Infants were praised for selecting the correct object. If infants selected the incorrect target, the experimenter asked, “Did you find it?” Once infants selected the correct target, the training phase started.

Training phase

In the training phase, the experimenter garnered the infant’s attention to a pair of novel toys, a wooden nut-and-bolt toy and a blue cylindrical rattle, by modeling their function twice (the wooden toy was spun, the rattle was shaken). Subsequently, both objects were given to the infant to explore for a period of 15 sec. Both the first toy being manipulated and the side in which it was placed in front of the experimenter were counterbalanced. While the infant was attending to the non-target object, the experimenter picked up the target object and labeled it by saying, “It’s a Dax,” (or Muron for French speakers) four times. The same novel object was labeled four times and was always given this same label. Afterward, the experimenter returned the target object to the infant so that both objects would be available for the infant to play with, for a period of up to 60 sec.

Test phase

During the test phase, the experimenter administered two types of trials to examine infants’ comprehension of the novel and familiar word. For each trial, the experimenter presented the infant with either one of two pairs of objects on a tray: two familiar objects or two novel objects. The same object pairs were used across all four trials. The experimenter then requested one of the objects by saying, “Where is the X? Give me the X,” before sliding the tray over to the infant to choose one of the objects. To avoid prompting the child during this request, the experimenter only looked at the infant, and never at the tray. There were eight trials in total in which four familiar word trials were alternated with four novel word trials. The location of the objects on the tray, the novel target object, as well as which type of trial (familiar or novel) was presented first, was counterbalanced across participants.

Coding and reliability

Several behaviors were coded during the training phase. Similar to Baldwin (1993), we coded whether infants disengaged from their own toy and followed the gaze of the speaker to map the referent of the label so that infants received a proportion of disengagement score out of the total number of training trials (of 4). We additionally coded the total proportion of time infants spent looking at the speaker during the four instances of word labeling, to assess whether there were differences across condition in terms of attentiveness. During the test phase, infants’ word comprehension was assessed, based on which object in the pair infants chose first, according to infants’ first touch. If both toys were chosen simultaneously, the trial was repeated by asking infants to show their parent the toy (the toy infants chose during this request was coded as their selection). In addition, infants were only inferred to have understood the demands of the task if their comprehension on the familiar trials was above that expected by chance. This task therefore generated two scores measuring the proportion of trials during which infants selected the correct target, one for novel words (of 4) and one for familiar words (of 4). Inter-rater reliability for the proportion of correct trials for novel and familiar words was r = .99 (range = .89–1.00).

Rational imitation task

The imitation task was adapted from Schwier et al. (2006). A toy dog and a small wooden house (37 × 25.5 × 22.5 cm) were used. The colorful house was comprised of a door and window in the front, a chimney in the roof, and a concealed backdoor in the rear.

Demonstration and test phases

The doghouse was placed on the table, in front of the infant, wherein the door to the doghouse was shown to be open. The experimenter drew the infant’s attention by calling the infant’s name, and only proceeded with the demonstration when the infant was attending. The experimenter began by tapping the open door twice and saying, “Look, the door is open!” She then started to make the dog approach the open door in an animated fashion, paused it in front of the door to make two short forward motions, and then moved the dog up and through the chimney into the house, while saying “Youpee!” Finally, the experimenter retrieved the dog through a concealed backdoor, placed both the dog and house in front of the infant, and stated, “Now it’s your turn.” The infant was given 30 sec to respond. If the child placed the dog in the doghouse at any point during the 30 sec, the experimenter retrieved it and returned it to the child. At the end of this response period, the experimenter repeated the entire process, including a demonstration and response period, for a second trial.

Coding and reliability

The imitation task was coded similarly to Schwier et al. (2006), based on whether the infant attempted to imitate the experimenter’s actions on each trial. Imitation was defined as copying the experimenter’s exact means of putting the dog through the chimney and coded as 1. Emulation, that is copying the experimenter’s end goal of putting the dog in the house (through the door), was coded as 0. This created a total imitation score (maximum score = 2), which was then converted to a score indicating the total proportion of successful imitation. The inter-rater reliability for success scores on the imitation task was r = .95.

Instrumental helping task

This task was adapted from one of Warneken and Tomasello’s (2006) Out-of-reach tasks (the Paperball task) and thus incorporated a 30 sec response period, repeated over three trials. Similar ostensive cues were used as in the rational imitation task, in that infants were called by their name at the outset of the task, with the task proceeding only if infants attended to the experimenter’s demonstration.

Demonstration and test phases

The infant watched as the experimenter picked up all three colored plastic blocks on her side using a pair of child-safe tongs, placed them in a yellow plastic bucket, and then tried unsuccessfully to reach for a block on the child’s side of the table. The experimenter reached for each of three blocks (placed one at a time in front of the infant) for a period of 30 sec. After the experimenter alternated looks between the block and infant for the first 20 sec of this 30 sec response period (see Warneken & Tomasello, 2006, for details), the final 10 sec consisted of her verbally clarifying the situation for the infant, saying, “I can’t reach!”

Coding and reliability

Infants were considered to help if they either moved the blocks closer to the experimenter or placed them in her tongs. Infants’ performance on all three trials was averaged together, creating a total proportion of success score (of 3). Inter-rater reliability was in perfect agreement for infants’ helping, r = 1.00.

RESULTS

Preliminary analyses

Infants did not differ with regard to the number of words in their productive vocabulary (as measured by the MCDI) across the reliable (M = 21.83, SD = 17.83) and unreliable condition (M = 17.08, SD = 9.95), t(47) = 1.16, p = .25, Cohen’s d = 0.33. In addition, the number of words infants knew that the speaker labeled in the reliability task (of four) in the reliable (M = 3.80, SD = 0.41) and unreliable (M = 3.88, SD = 0.34) condition did not differ, t(47) = 1.16, p = .25, Cohen’s d = 0.33. There was no effect of these two variables on infants’ performance on the main variables (novel word learning, proportion of trials infants’ imitated, proportion of helping), nor was there an effect for age, gender, language, or trial order. Therefore results were collapsed across these variables. Data from one infant were removed from the analyses for the training task only because her face was out of view, and therefore, her looking times could not be coded. A summary of the main findings from the three experimental tasks, according to condition, can be found in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Mean scores on the word learning, rational imitation, and instrumental helping tasks, according to condition

| Mean (SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Task | Variable | Reliable | Unreliable |

| Word learning | Proportion of correct selections during novel trials | 59.38% (23.09)* | 42.00% (31.22) |

| Rational imitation | Proportion of trials infants imitated | 54.35% (42.41)* | 28.00% (32.53) |

| Instrumental helping | Proportion of total acts of helping | 73.63% (41.69) | 76.00% (41.42) |

Significant condition difference (p ≤ .05).

Reliability task

Infants from both conditions were equally attentive during the labeling of the toy, as indicated by the high proportion of time infants spent looking at the speaker when she was labeling the toys, during Phase Two (reliable: M = 99.40%, SD = 21.25; unreliable: M = 98.46%, SD = 43.34), t(46) = −0.94, p = .35, Cohen’s d = 0.03. A condition (reliable vs. unreliable) by target of looking (experimenter vs. parent vs. toy) mixed factorial ANOVA was computed on infants’ proportion of total looking time during Phase Three, once infants had access to the toy. There was no effect of condition, F(2, 92) = 1.18, p = .28, gp2 = .03, nor any significant interaction, F(2, 92) = 1.39, p = .25, gp2 = .03. There was a significant main effect of target, F(2, 92) = 103.71, p = .00, gp2 = .69, with infants spending the greatest proportion of trial time looking at the toy (M = 47.76%, SD = 15.19) than at either the experimenter (M = 32.63%, SD = 12.01) or their parent (M = 6.65%, SD = 9.20). This suggests that infants from both conditions were focused on the experimenter’s cues during labeling and were as likely to subsequently engage with the toy regardless of the accuracy of the labeling.

Word learning task

Several behaviors were coded during the training phase to insure that infants were equally attentive to the speaker across conditions. With regard to the proportion of trials (of 4) that infants disengaged from their own toy to follow the direction of the speaker’s gaze to the object being labeled, there was no difference between the reliable (M = 87.50%, SD = 18.06) and the unreliable (M = 92.02%, SD = 11.89) condition, t(47) = −1.04, p = .30, Cohen’s d = .30. In addition, we coded for the total proportion of trial time infants spent looking at the speaker during object labeling. Four infants from each condition were excluded in this analysis, as their face was out of view for parts of the duration of the trial; therefore, while their initial disengagement could be coded, their total looking time at the speaker could not be coded reliably. It was found that infants in the unreliable condition (M = 49.68%, SD = 21.23) looked longer at the speaker during labeling than those in the reliable condition, (M = 34.52%, SD = 18.84), t(39) = −2.42, p = .02, Cohen’s d = .76. Subsequent analyses showed that the proportion of times infants disengaged (r = .01, p = .93) and the proportion of time infants spent attending to the speaker during novel object labeling (r = −.18, p = .27) were unrelated to infants’ successful selection of the target object on novel word trials. Therefore results were collapsed across these factors.

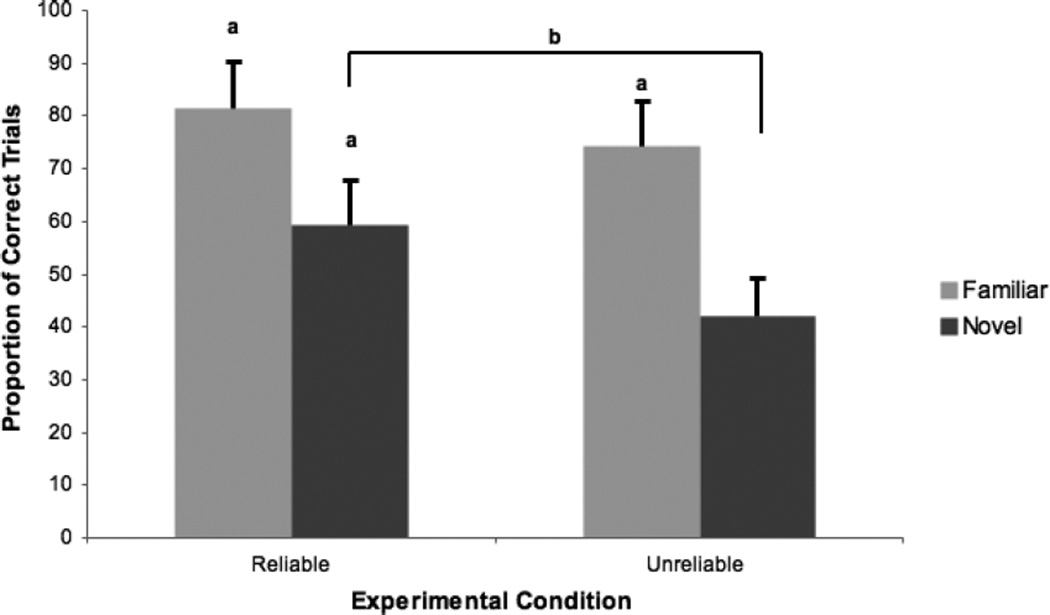

To examine differences in performance across conditions, a condition (reliable vs. unreliable) by trial type (familiar vs. novel) mixed factorial ANOVA was computed, with proportion of correct object choices as the dependent variable. A significant main effect was found for type of word wherein, overall, infants did worse on novel trials (M = 50.51, SD = 28.64) than on familiar trials (M = 77.88, SD = 20.41), F(1, 47) = 29.38, p = .00, gp2 = .39. Infants also did better as a function of condition, with those in the reliable group (M = 70.50, SD = 20.33) outperforming those in the unreliable group (M = 58.20, SD = 27.34), F(1, 47) = 6.75, p .01, gp2 = .13. However, the ANOVA failed to yield a significant interaction between trial type and condition, F(1, 47) = 1.01, p = .32, gp2 = .02, suggesting that the effect of the speaker’s reliability is equivalent on infants’ subsequent recognition of both familiar and novel words.

In addition, one-sample t-tests were conducted to compare infants’ selection of the correct target word on novel and familiar word trials to chance (50%). Overall, infants performed better than chance on familiar trials in both the reliable (M = 81.58%, SD = 17.41), t(23) = 8.89, p = .00, 95% CI [0.24, 0.39] and unreliable conditions (M = 74.32%, SD = 22.71), t(24) = 5.36, p = .00, 95% CI [0.15, 0.34], indicating that they understood the demands of the task. In contrast, only infants in the reliable condition performed greater than chance on novel trials (M = 59.38%, SD = 23.09), t(23) = 1.99, p = .05, 95% CI [−0.00, 0.19], whereas those in the unreliable condition did not (M = 42.00%, SD = 31.22), t(24) = −1.28, p = .21, 95% CI [−0.21, 0.05]. Nonparametric analyses using the Mann–Whitney U-test confirmed this pattern of findings (see Figure 1). Specifically, it indicated that there were differences across conditions on novel label trials, U(47) = 204.00, z = −1.99, p = .05, r = −.29, but not on familiar label trials, U(47) = 247.60, z = −1.12, p = .26, r = .16.

Figure 1.

Infants’ proportion of correct trials on the word learning task, for familiar and novel trials, according to condition. Error bars refer to the standard errors. (a) indicates values greater than chance (p < .05). (b) indicates significant condition difference (p < .05).

Rational imitation task

To compare infants’ imitative behavior, the proportion of trials infants put the dog in the house was used, as some infants did not respond on both trials (5 in the unreliable condition and 2 in the reliable condition). In addition, one infant in the reliable condition did not complete the task and was not included in the analyses. All infants were found to be 100% attentive to the model’s demonstration during the entirety of its duration. It was found that 16 of 23 infants (70%) in the reliable condition put the dog in the chimney on one or both trials, whereas only 12 of 25 infants (48%) in the unreliable condition did so, χ2(2, 46) = 6.71, p = .04, ϕ = .37. A group comparison using the Mann–Whitney U-test found that infants used the chimney in a greater proportion of trials in the reliable (M = 54.35%, SD = 42.41) than in the unreliable condition (M = 28.00%, SD = 32.53), U(46) = 187.50, z = −2.21, p = .03, r = .33. Similar to Schwier et al. (2006) finding, this result was due to differences on the second trial. Specifically, on the first trial, 12 of 23 infants (52%) in the reliable condition compared with 9 of 25 infants (36%) in the unreliable condition used the chimney, χ2(1, 46) = 1.27, p = .26, ϕ = .16. In contrast, on the second trial, 13 of 21 infants (62%) in the reliable condition compared with 2 of 20 infants (10%) in the unreliable condition used the chimney, χ2(1, 39) = 11.90, p = .001, ϕ = .54.

Instrumental helping task

All infants were found to be 100% attentive to the speaker’s demonstration. Consequently, a score representing infants’ total proportion of helping behaviors across the three trials was computed. While there were some infants who chose not to help at all (5 infants in each condition), 72.0% and 66.7% in the unreliable and reliable condition, respectively, completed all three trials. The majority of infants chose to help as both infants in the reliable (M = 73.63, SD = 41.69) and unreliable condition (M = 76.00, SD = 41.42) displayed high proportions of helping across the three trials. In contrast to infants’ learning behavior, an independent t-test failed to find differences in infants’ proportion of helping, t(47) = 0.20, p = .84, Cohen’s d = 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Only recently have the effects of a model’s epistemic reliability been examined as they impact infants’ behavior. To date, no study has addressed whether infants modify their learning according to a speaker’s verbal accuracy around the time of the “language explosion” or the scope of this effect on a range of infants’ learning and prosocial behaviors. The present findings are therefore important because they provide three main contributions: (1) 18-month-olds’ novel word mapping and familiar word comprehension are impacted when tested by an inaccurate speaker, the earliest age ever to report such an effect; (2) the effect of a speaker’s accuracy extends beyond the domain of language, influencing infants’ willingness to imitate the speaker’s actions; and (3) infants’ prosocial behaviors such as instrumental helping remain uninfluenced by a speaker’s verbal accuracy.

Previous research with infants at 16 months of age has shown that they respond differently to an accurate versus an inaccurate speaker as well as to the object that receives a correct or incorrect label, based on their looking and pointing behavior (Koenig & Echols, 2003; Pea, 1982). The current study found that despite the experimenter’s unexpected behavior when mislabeling familiar objects, infants maintained their attention toward each speaker equally during the labeling phase and were as likely to engage with the toy afterward. While these findings appear to conflict with one another, there are methodological differences between the studies that make direct comparisons difficult. First, the set-up in Koenig and Echols’ (2003) study allowed them to clearly assess differential looking time to the experimenter and the object being labeled, which was projected ahead of the experimenter on a screen. In the current study, the speaker was directly in line of (and behind) the toy being labeled and so infants’ gaze and attention to the experimenter’s labeling display could not be teased apart from their attention to the object being labeled. Thus, infants’ interest in the toy being labeled by the experimenter may have masked their differential treatment of the experimenter. Furthermore, the current study reported looking times at the toy following the labeling phase, once infants had access to the toy. As infants in Koenig and Echols’ study never had access to the toy either during or following labeling, our reported looking times may reflect infants’ desire to explore the toy, which may have overridden any preference they may have at this age for objects that are identified correctly. Nevertheless, it appears that infants were indeed able to detect the speaker’s inaccuracy in light of their building receptive vocabulary as revealed by their differential treatment of the speaker in subsequent tasks.

Confirming our main hypothesis, infants performed more poorly on a word learning task when interacting with a speaker who demonstrated incompetence in object labeling. Specifically, 18-month-old infants performed less well during both novel and familiar word trials when tested by a speaker who previously incorrectly labeled familiar objects. Thus, it appears that not only was infants’ ability to map a novel word to a novel object impaired but also their overall trust that the speaker was requesting the correct object during any aspect of the test phase. Infants might have found it surprising that a speaker who had just shown a lack of knowledge about familiar object labels was later able to request a familiar object by its appropriate name (see Koenig & Woodward, 2010 for a similar interpretation). Nevertheless, chance analyses indicated that infants in both conditions performed at levels higher than would be expected by chance on familiar word comprehension trials and that only infants in the reliable condition showed a robust knowledge of the novel object labels. Taken together, it therefore appears that infants in the unreliable condition used their knowledge of the speaker’s verbal inaccuracy to guide their behavior during all labeling contexts.

Research examining how word learning is tempered by the reliability of the source has largely been restricted to work with preschoolers (e.g., Jaswal & Neely, 2006; Koenig & Harris, 2005b; Pasquini et al., 2007; Scofield & Behrend, 2008). In addition, previous research with 24-month-olds has been somewhat inconsistent, demonstrating that at times infants actually do learn novel words from sources that have previously been verbally inaccurate (Koenig & Woodward, 2010; Krogh-Jespersen & Echols, 2012). The current study used a procedure that required infants to disengage from their own toy in order to attend to the pragmatic cues of the speaker and correctly map a new label to an object that was the focus of her attention. Although it was a challenging procedure, infants across both conditions displayed equally high levels of disengagement from their own toy to follow the speaker’s gaze and map the referent of her novel label. Interestingly, infants in the unreliable condition spent significantly more time looking at the speaker than those in the reliable condition, suggesting that infants’ differential word learning was not due to a lack of attention to the speaker’s utterances.

In addition, and confirming our second hypothesis, epistemic reliability also extended its influence beyond the domain of language, reducing infants’ willingness to attribute rational intentions to the speaker. Thus similar to preschoolers (Koenig & Harris, 2005a; Rakoczy et al., 2009), infants in the current study made an assessment about the speaker’s general level of competence, and used this information to infer whether the speaker was conventional enough to learn from in another epistemic context. As imitation is a cultural learning activity, there are times when it is important to perform exactly as the model does and other times when it is not (Schwier et al., 2006). Indeed, infants exposed to an inaccurate speaker erred on emulation rather than imitation, thus overriding infants’ strong inclination to be “overimitators” and imitate an adult’s actions regardless of the actions’ efficiency (Kenward, 2012; Lyons, Young, & Keil, 2007; Nielsen & Tomaselli, 2010) or relevance (Gergely et al., 2002; Zmyj, Daum, & Ascherslebenb, 2009). Therefore, our results extend research demonstrating that a source’s unreliable ostensive and communicative cues lead infants to infer that the source’s acts are unlikely to be relevant (Poulin-Dubois et al., 2011; Zmyj et al., 2010), by suggesting that a source’s verbal inaccuracy does as well.

Taken together, it appears that infants’ differential response to verbally accurate versus inaccurate speakers indicates a robust understanding of the speaker’s reliability and additionally, rationality. However, alternative explanations are possible and therefore need to be ruled out. One possibility is that infants may have found that the speaker was silly, in terms of lacking mentalistic ability or intent (e.g., Schwier et al., 2006). Specifically, they may have considered someone who inaccurately labeled familiar objects as not having firm understanding about object properties and relations, which would have marked her consequent demonstrations as lacking in intentional purpose. An avenue for future research would thus be to examine whether a person’s ignorance of familiar object labels would yield similar results, as an ignorant person is not silly but rather unconventional and uninformed. Indeed, it has recently been found that both 18- and 24- month-olds prefer not to learn a novel word from an ignorant speaker (Brooker & Poulin-Dubois, 2012; Krogh-Jespersen & Echols, 2012), with the former study demonstrating that 18-month-olds also prefer not to imitate the speaker’s irrational actions. Thus, infants’ differential responses are probably not due to their attributions of the speaker as silly but rather as an inaccurate, unconventional speaker. It has been suggested that infants are more likely to imitate others who are conventional and culturally similar to them (Meltzoff, 2007; Schmidt & Sommerville, 2011; Tomasello, 1999), with preschoolers shown to prefer to learn new words and even endorse the use of a new tool from culturally similar as opposed to dissimilar sources (see Harris & Corriveau, 2011 for review).

A second possible explanation is that infants may have failed to form strong internal representations of the speaker’s actions, making them harder to remember. Indeed, it has been suggested that infants might weakly encode an inaccurate speaker’s semantic utterances (e.g., Koenig & Woodward, 2010; Sabbagh & Shafman, 2009). We assessed infants’ attention during the speaker’s demonstrations by: (1) recording the time infants spent looking at the speaker during her initial labeling demonstration, (2) examining and ensuring that infants displayed a similar ability to shift their attention toward the speaker and the object of her referent during the word learning task, (3) recording the time infants spent looking at the speaker during her novel labeling demonstration (also during the word-learning task), and (4) proceeding with the rational imitation and instrumental helping tasks only if infants were attentive to the experimenter’s actions. As indicated previously, both groups of infants spent equal amounts of time looking to the speaker’s initial reliability manipulation, whereas infants in the unreliable condition actually looked longer at the speaker during her labeling of the novel object during the word learning task. Therefore, it is unlikely that a version of the unreliable speaker accounts for the current findings. Nonetheless, these data do not inform about the quality or robustness of infants’ processing; it is possible that infants were drawn to the unreliable speaker but shallowly encoded the information that she provided. It has been proposed that infants possess a negativity bias in that they display differential attention to others on account of their aversive traits or characteristics (e.g., Vaish, Grossmann, & Woodward, 2008). Thus, a future direction for research would be to examine infants’ visual processing of the experimenter in a nonlearning task, potentially through the use of eye tracking technology, to assess whether infants do indeed spend greater amounts of time processing the face of the unreliable speaker or model. Certainly, eye-gaze tracking can specify which part of a stimulus someone is thoroughly processing or focusing his or her attention on (Irwin, 2004) and has been used with infants in order examine how they focus on social events and attend to others’ manual actions (Gredebäck, Johnson, & von Hofsten, 2010).

Finally, the current study also included a nonlearning prosocial task, specifically an instrumental helping task, to tease apart whether speaker accuracy generates a strong “halo” effect. The present findings confirmed our hypothesis that infants’ instrumental helping is not affected by the speaker’s verbal accuracy. Instrumental helping has been described as an altruistically motivated, nondiscriminatory behavior among young infants (Warneken & Tomasello, 2009), wherein the actions themselves are highly reinforcing, and the relationship between actor and object is salient and easy to infer (i.e., trying to grasp an out-of-reach object, Brownell, Svetlova, & Nichols, 2009; Meltzoff, 2007; Svetlova, Nichols, & Brownell, 2010). Perhaps slightly older infants would have been more likely to be affected by the reliability of the person with whom they interact (e.g., Dunfield & Kuhlmeier, 2010), and thus this issue remains an area for future research. Furthermore, as research has shown that a model who is more familiar (Volland, Ulich, & Fischer, 2004), has negative intentions (Dunfield & Kuhlmeier, 2010), and lacks in reciprocation (Olson & Spelke, 2008) can influence older children’s natural tendency to help, it is important to examine whether these aspects of a model’s reliability would also be more influential on infants’ helping.

In sum, infants appear to be precocious selective learners who are able to use their recognition of a speaker’s reliability after only four instances of labeling to guide their learning and behavior both in the domain of language and in the realm of cultural and imitative acts. This is a remarkable finding, given that attenuation of learning from a verbally inaccurate source in domains other than language has not been seen in children younger than 4 years of age (i.e., Fusaro et al., 2011; Rakoczy et al., 2009). Previous research has shown that infants are inclined to learn new words and imitate irrational actions in contexts that are driven by ostensive cues (Akhtar, Carpenter, & Tomasello, 1996; Baldwin & Moses, 1996, 2001; Brugger, Lariviere, Mumme, & Bushnell, 2007; Csibra & Gergely, 2009; Király, Csibra, & Gergely, 2004; Király, 2009). The findings from the current study suggest that even a brief exposure to an inaccurate labeler is enough to override infants’ default tendency to trust cues presented by others and learn from these displays. As infants are universal novices who must rely on others to make sense of the world around them, the ability to be selective when deciding whom to learn from is especially important during this critical developmental period.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported in part by grants from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC). Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HD068458. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to thank Alexandra Polonia, Katherine Gittins, and Jessica Shea for their help in data collection as well as coding, to ensure reliability.

REFERENCES

- Akhtar N, Carpenter M, Tomasello M. The role of discourse novelty in early word learning. Child Development. 1996;67:635–645. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin DA. Infants’ ability to consult the speaker for clues to word reference. Journal of Child Language. 1993;20:395–418. doi: 10.1017/s0305000900008345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin DA, Moses LJ. The ontongeny of social information gathering. Child Development. 1996;67:1915–1939. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin DA, Moses LJ. Links between social understanding and early word learning: Challenges to current accounts. Social Development. 2001;10:309–329. [Google Scholar]

- Birch SAJ, Vauthier SA, Bloom P. Three- and four-year-olds spontaneously use others’ past performance to guide their learning. Cognition. 2008;107:1018–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker I, Poulin-Dubois D. ‘Nice but ignorant’ or ‘Mean but knowledgable’: What types of reliability affect infants’ learning and prosocial behaviours?. Poster presented at the XVIII Biennial International Conference on Infant Studies; Minneapolis, MN. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Brosseau-Liard PE, Birch SAJ. ‘I bet you know more and are nicer too!’: What children infer from others’ accuracy. Developmental Science. 2010;13:772–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell CA, Svetlova M, Nichols S. To share or not to share: When do toddlers respond to another’s needs? Infancy. 2009;14:117–130. doi: 10.1080/15250000802569868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugger A, Lariviere LA, Mumme DL, Bushnell EW. Doing the right thing: Infants’ selection of actions to imitate from observed event sequences. Child Development. 2007;78:806–824. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter M, Akhtar N, Tomasello M. Fourteen-through 18-month-old infants differentially imitate intentional and accidental actions. Infant Behavior and Development. 1998;21:315–330. [Google Scholar]

- Chow V, Poulin-Dubois D, Lewis J. To see or not to see: Infants prefer to follow the gaze of a reliable looker. Developmental Science. 2008;11:761–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clément F, Koenig M, Harris PL. The ontogenesis of trust. Mind and Language. 2004;19:360–379. [Google Scholar]

- Corriveau K, Harris PL. Preschoolers continue to trust a more accurate-informant 1 week after exposure to accuracy information. Developmental Science. 2009;12:188–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csibra G, Gergely G. Natural pedagogy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2009;13:148–153. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diesendruck G, Carmel N, Markson L. Children’s sensitivity to the conventionality of sources. Child Development. 2010;81:652–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunfield KA, Kuhlmeier VA. Intention-mediated selective helping in infancy. Psychological Science. 2010;20:1–5. doi: 10.1177/0956797610364119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einav S, Robinson EJ. When being right is not enough: Four-year-olds distinguish knowledgeable informants from merely accurate informants. Psychological Science. 2011;10:1250–1253. doi: 10.1177/0956797611416998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenson L, Dale PS, Reznick JS, Thal D, Bates E, Hartung JP, et al. Technical manual for the MacArthur Communicative Development Inventories. San Diego, CA: San Diego State University; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Fenson L, Pethick S, Renda C, Cox JL, Dale PS, Reznick JS. Short form versions of the Macarthur Communicative Development Inventories. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2000;21:95–115. [Google Scholar]

- Fusaro M, Corriveau KH, Harris P. The good, the strong, and the accurate: Preschoolers’ evaluations of informant attributes. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2011;110:561–574. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gergely G, Bekkering H, Király I. Rational Imitation in Preverbal Infants. Nature. 2002;415:755. doi: 10.1038/415755a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gergely G, Csibra G. The social construction of the cultural mind: Imitative learning as a mechanism of human pedagogy. Interaction Studies. 2005;6(3):463–481. [Google Scholar]

- Gergely G, Csibra G. Sylvia’s recipe: The role of imitation and pedagogy in the transmission of human culture. In: Enfield NJ, Levinson SC, editors. Roots of human Sociality: Culture, cognition, and human interaction. Oxford: Berg Publishers; 2006. pp. 229–255. [Google Scholar]

- Gergely G, Egyed K, Király I. On pedagogy. Developmental Science. 2007;10:139–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfield BA, Reznick JS. Early lexical acquisition: Rate, content and the vocabulary spurt. Journal of Child Language. 1990;17:171–183. doi: 10.1017/s0305000900013167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gredebäck G, Johnson S, von Hofsten C. Eye tracking in infancy research. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2010;35:1–19. doi: 10.1080/87565640903325758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurteen PM, Horne PJ, Erjavec M. Rapid word learning in 13- and 17-month-olds in a naturalistic two-word procedure: Looking versus reaching measures. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2011;109:201–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PL. Trust. Developmental Science. 2007;10:135–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PL, Corriveau KH. Young children’s selective trust in informants. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 2011;366:1179–1187. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay DF. The roots and branches of human altruism. The British Journal of Psychology. 2009;100:473–479. doi: 10.1348/000712609X442096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay DF, Caplan M, Castle J, Stimson CA. Does sharing become increasingly “rational” in the second year of life. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:987–993. [Google Scholar]

- Heyes CM. Imitation and culture: Longevity, fecundity and fidelity in social transmission. In: Galef B, Mainardi M, Valsecchi P, editors. Behavioral aspects of feeding. Switzerland: Harwood; 1994. pp. 271–287. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin DE. Fixation location and fixation duration as indices of cognitive processing. In: Henderson JM, Ferreira F, editors. The Interaction of language, vision, and action: Eye movements and the visual world. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2004. pp. 105–133. [Google Scholar]

- Jaswal VK, Malone LS. Turning believers into skeptics: 3-Year-olds sensitivity to cues to speaker credibility. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2007;8:263–283. [Google Scholar]

- Jaswal VK, Neely LA. Adults don’t always know best: Preschoolers use past reliability over age when learning new words. Psychological Science. 2006;17:757–758. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katerelos M, Poulin-Dubois D, Oshima-Takane Y. A cross-linguistic study of word-mapping in 18- to 20-month-old infants. Infancy. 2011;16:508–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2010.00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenward B. Over-imitating preschoolers believe unnecessary actions are normative and enforce their performance by a third party. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2012;112:195–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Kalish CW, Harris PL. Speaker reliability guides children’s inductive inferences about novel properties. Cognitive Development. 2012;27:114–125. [Google Scholar]

- Király I. The effect of the model’s presence and of negative evidence on infants’ selective imitation. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2009;102:14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Király I, Csibra G, Gergely G. The role of communicative-referential cues in observational learning during the second year. Poster presented at the 14th Biennial International Conference on Infant Studies; Chicago, IL. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig MA, Clement F, Harris PL. Trust in testimony: Children’s use of true and false statements. Psychological Science. 2004;10:694–698. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig MA, Echols CH. Infants’ understanding of false labeling events: The referential role of words and the people who use them. Cognition. 2003;87:181–210. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(03)00002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig MA, Harris PL. Preschoolers mistrust ignorant and inaccurate speakers. Child Development. 2005a;76:1261–1277. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig MA, Harris PL. The role of social cognition in early trust. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2005b;9:457–459. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig MA, Woodward AL. Twenty-four-month-olds’ sensitivity to the prior inaccuracy of the source. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:815–882. doi: 10.1037/a0019664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh-Jespersen S, Echols CH. The influence of speaker reliability on first versus second label learning. Child Development. 2012;83:581–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lizkowski U, Carpenter M, Striano T, Tomasello M. 12- and 18-month-ols point to provide information for others. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2006;7:173–187. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons DE, Young AG, Keil FC. The hidden structure of overimitation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:19751–19756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704452104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascaro O, Sperber D. The Moral, Epistemic, and Mindreading Components of Children’s Vigilance towards Deception. Cognition. 2009;112:367–380. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzoff AN. ‘Like me’: A foundation for social cognition. Developmental Science. 2007;10:126–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00574.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen M, Tomaselli K. Overimitation in Kalahari Bushman Children and the Origins of Human Cultural Cognition. Psychological Science. 2010;21:729–736. doi: 10.1177/0956797610368808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell L, Poulin-Dubois D, Demke T, Guay A. Can infants use nonhuman agent’s gaze direction to establish word-object relations? Infancy. 2009;14:414–438. doi: 10.1080/15250000902994073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olineck KM, Poulin-Dubois D. Infants’ ability to distinguish between intentional and accidental action and its relation to internal state language. Infancy. 2005;8:91–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327078in0801_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson KR, Spelke ES. Foundations of cooperation in young children. Cognition. 2008;108:222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquini ES, Corriveau KH, Koenig M, Harris PL. Preschoolers monitor the relative accuracy of informants. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1216–1226. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.5.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pea RD. Origins of verbal logic: Spontaneous denials by two- and three-year-olds. Journal of Child Language. 1982;9:597–626. doi: 10.1017/s0305000900004931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin-Dubois D, Brooker I, Polonia A. Infants prefer to imitate a reliable person. Infant Behaviour and Development. 2011;34:303–309. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin-Dubois D, Chow V. The effect of a looker’s past reliability on infants’ reasoning about beliefs. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:1576–1582. doi: 10.1037/a0016715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakoczy H, Warneken F, Tomasello M. Young children’s selective learning of rule games from reliable and unreliable models. Cognitive Development. 2009;24:61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Rendell L, Fogarty L, Hoppitt WJE, Morgan TJH, Webster MM, Laland KN. Cognitive culture: Theoretical and empirical insights into social learning strategies. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2011;15:68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reznick JS, Goldfield BA. Rapid change in lexical development. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28:406–413. [Google Scholar]

- Ross HS, Lollis SP. Communication within infant social games. Developmental Psychology. 1987;23:241–248. [Google Scholar]

- Sabbagh MA, Baldwin D. Learning words from knowledgeable versus ignorant speakers: Links between preschoolers’ theory of mind and semantic development. Child Development. 2001;72:1054–1070. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbagh MA, Shafman D. How children block learning from ignorant speakers. Cognition. 2009;112:415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt MFH, Sommerville JA. Fairness expectations and altruistic sharing in 15-month-old human infants. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:1–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwier C, Van Maanen C, Carpenter M, Tomasello M. Rational Imitation in 12 Month-Old Infants. Infancy. 2006;10:303–311. [Google Scholar]

- Scofield J, Behrend DA. Learning words from reliable and unreliable speakers. Cognitive Development. 2008;23:278–290. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel DM, Corriveau KH. Children monitor individuals’ expertise for word learning. Child Development. 2010;81:669–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sodian B, Thoermer C. Infants’ understanding of looking, pointing, and reaching as cues to goal-directed action. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2004;5:289–316. [Google Scholar]

- Sperber D, Clément F, Heintz C, Mascaro O, Mercier H, Origgi G, Wilson D. Epistemic Vigilance. Mind and Language. 2010;25:359–393. [Google Scholar]

- Svetlova M, Nichols SA, Brownell CA. Toddlers’ prosocial behaviour: From instrumental to empathic to altruistic helping. Child Development. 2010;81:1814–1827. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01512.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M, Esbensen BM, Bennett RT. Children’s understanding of knowledge acquisition: The tendency for children to report that they have always known what they have just learned. Child Development. 1994;65:1334–1351. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M. The cultural origins of human cognition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M, Carpenter M, Call J, Behne T, Moll H. Understanding and sharing intentions: The origins of cultural cognition. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2005;28:675–735. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X05000129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaish A, Carpenter M, Tomasello M. Young children selectively avoid helping people with harmful intentions. Child Development. 2010;81:1661–1669. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaish A, Grossmann T, Woodward A. Not all emotions are created equal: The negativity bias in social-emotional development. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:383–403. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volland C, Ulich D, Fischer A. Who deserves help? The age-dependent influence of recipient characteristics on the prosociality of children (in German) Zeitschrift für Entwixklungspsychologie und Pädagogische Psychologie. 2004;36:69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Warneken F, Tomasello M. Altruistic helping in human infants and young chimpanzees. Science. 2006;311:1301–1303. doi: 10.1126/science.1121448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warneken F, Tomasello M. Helping and cooperation at 14 months of age. Infancy. 2007;11:271–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2007.tb00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warneken F, Tomasello M. The roots of human altruism. British Journal of Psychology. 2009;100:455–471. doi: 10.1348/000712608X379061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zmyj N, Buttelmann D, Carpenter M, Daum MM. The reliability of a model influences 14-month-olds’ imitation. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2010;106:208–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zmyj N, Daum MM, Ascherslebenb G. The development of rational imitation in 9- and 12-month-old infants. Infancy. 2009;14:131–141. doi: 10.1080/15250000802569884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]