Abstract

Background

Despite the availability of evidence-based guidance, many patients with type 2 diabetes do not achieve treatment goals.

Aim

To guide quality improvement strategies for type 2 diabetes by synthesising qualitative evidence on primary care physicians’ and nurses’ perceived influences on care.

Design and setting

Systematic review of qualitative studies with findings organised using the Theoretical Domains Framework.

Method

Databases searched were MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycInfo, and ASSIA from 1980 until March 2014. Studies included were English-language qualitative studies in primary care of physicians’ or nurses’ perceived influences on treatment goals for type 2 diabetes.

Results

A total of 32 studies were included: 17 address general diabetes care, 11 glycaemic control, three blood pressure, and one cholesterol control. Clinicians struggle to meet evolving treatment targets within limited time and resources, and are frustrated with resulting compromises. They lack confidence in knowledge of guidelines and skills, notably initiating insulin and facilitating patient behaviour change. Changing professional boundaries have resulted in uncertainty about where clinical responsibility resides. Accounts are often couched in emotional terms, especially frustrations over patient compliance and anxieties about treatment intensification.

Conclusion

Although resources are important, many barriers to improving care are amenable to behaviour change strategies. Improvement strategies need to account for differences between clinical targets and consider tailored rather than ‘one size fits all’ approaches. Training targeting knowledge is necessary but insufficient to bring about major change; approaches to improve diabetes care need to delineate roles and responsibilities, and address clinicians’ skills and emotions around treatment intensification and facilitation of patient behaviour change.

Keywords: diabetes mellitus, type 2; primary health care; qualitative research; quality improvement; systematic review

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus is a global health problem affecting both developed and resource-limited countries.1,2 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 347 million people worldwide have diabetes, with deaths from diabetes projected to double between 2005 and 2030.3 Diabetes also causes considerable morbidity related to macro- and microvascular damage, and to psychosocial sequelae,4–6 and incurs significant and growing healthcare costs.7

Despite the availability of evidence-based guidance,8–10 and encouraging trends in the delivery of care, many patients with diabetes do not achieve the recommended glycaemic, cholesterol, and blood pressure levels.2,11 Most routine diabetes management, particularly of type 2 diabetes, is undertaken in primary care, drawing on features of the chronic care model such as dedicated review clinics,12 and shared care with specialists.13

Interventions to improve diabetes care generally have modest effects.14 Understanding influences on clinical behaviour is critical in guiding the selection and enhancement of interventions to improve practice.15,16 Patient-reported influences on the receipt and outcome of diabetes care are well documented.17–21 However, much variation in delivery and outcomes is not readily explained by patient characteristics, and is likely to be attributable to clinician and organisational behaviour.22 Qualitative studies were reviewed that examined primary care clinicians’ perceived barriers to and enablers of recommended practice for type 2 diabetes.

METHOD

Search strategy

Search strategies were combined for papers on clinicians’ perceptions and type 2 diabetes from the Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group together with qualitative methodological filters (the full search strategy is available from the authors on request).23 MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycInfo, and ASSIA were searched from 1980, the year the WHO report recommended integrating diabetes care within community-based healthcare systems,24 until the first week in March 2014, and reference lists of included studies were hand searched.

Study selection

Qualitative studies were included that described primary care physicians’ or nurses’ perceptions of type 2 diabetes management. Papers were included that either focused on specific treatment goals (such as glycaemic control)8,11,25 or more general aspects of care. Papers were excluded that examined other specific care processes (for example, management of concurrent depression) and quantitative surveys.

Paired reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts of all identified references. Inconsistencies were examined in decisions after 100 and 500 references, and inclusion criteria were refined. Paired reviewers independently assessed full-text articles. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. Non-English studies were identified but their data were not extracted.

How this fits in

Type 2 diabetes is a global health problem with many patients failing to achieve recommended treatment goals. Most routine type 2 diabetes management is undertaken in primary care. Barriers to care include knowledge and resources, but also uncertainties about professional role boundaries, and clinicians’ anxieties regarding treatment decisions. Strategies to improve type 2 diabetes care need to address clinicians’ skills and emotions around treatment intensification and facilitation of patient behaviour change.

Data extraction

Single reviewers extracted data on study details, perceptions, and quality assessment. Perceived barriers and enablers to the 14 domains of the Theoretical Domains Framework26 were coded using NVivo 10 (further details are available from the authors on request). This framework draws on psychological theories to group influences on behaviour and hence categorise implementation problems.27,28 Data were further coded to treatment goals (such as glycaemic control) and as primarily clinician, patient, or organisational related.

A second reviewer checked data extraction and coding, resolving disagreement by discussion. Initial calibration exercises were undertaken involving independent data extraction and coding on a pilot sample of three papers and the coding was further clarified. Intra-coder reliability was judged to be adequate after recoding an early included study at the end of the data extraction phase.

Quality assessment

After initial calibration exercises one researcher assessed study quality using the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) checklist for qualitative studies.29

Data synthesis and analysis

The findings were organised within a grid comprising the 14 theoretical domains. Gaps were identified in the grid to highlight influences not reported in the literature. The relative proportions of patient, clinician, and organisational factors represented in each domain and for each targeted behaviour were assessed. In reporting results, physicians and nurses are referred to as ‘clinicians’ but separate terms are used when appropriate.

RESULTS

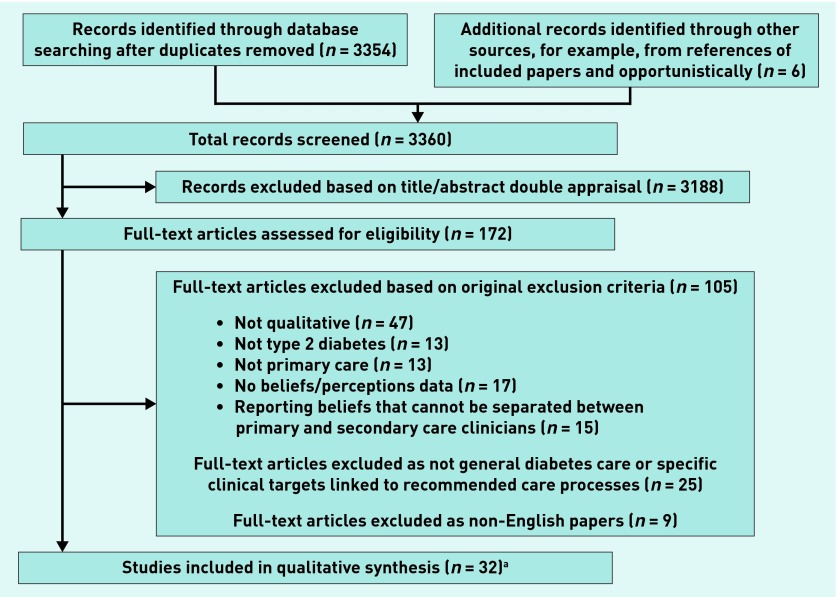

From 3360 records, 172 full-text papers were assessed, with 32 studies included in the qualitative synthesis (Figure 1 and Appendix 1). Over half of the studies included were from the US (11 studies) or the UK (seven). Nineteen studies conducted individual qualitative interviews (one structured, nine semi-structured, and nine unspecified), eight focus groups, and five combinations of these. The main treatment goals were general diabetes management in 17 studies, glycaemic control in 11 (nine focusing on insulin initiation), blood pressure in three studies, and cholesterol control in one.

Figure 1.

Flow of studies through review. aTwo papers describe data taken from the same study.30,31

Influences on clinical practice ranged across all 14 theoretical domains (Table 1; more detailed summaries grouped by glycaemic control and blood pressure are available from the authors on request). The most commonly occurring and salient domains comprised environmental context and resources, knowledge, and skills (often coded together), professional role and identity, and emotion.

Table 1.

Coding of extracts to Theoretical Domains Framework26 and clinical target

| Domain | Clinical target | Clinician-related factors | Patient-related factors | Organisational-related factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental context and resources | General | Families not invited for lifestyle modification discussions.48 | Patients’ socioeconomic situation, occupation, carer status, comorbidities, mobility problems, polypharmacy, and self-empowerment capacity acting as barriers to care.32,33,35,37,42,47–51 | Workload and time pressures; inadequate funding and staff numbers (clinical and administrative); role of structured management systems; access issues for patients, including to self-management education; mixed relationships and communication with specialist teams; limited services for specific patient-groups (for example, older people); role of insurance companies in driving disease-management activity; lack of public health support for prevention awareness; lack of agreed national management protocol; and continuing clinical education provision.32,34,35,37,40,42,45–49,51,52,53–55 |

| Glycaemic control | Nurses feeling isolated in role as single diabetes nurse in practice when considering converting to insulin.43 | Accommodating insulin therapy with patients’ lifestyles; patients’ ability to care for themselves adversely affected by physical impairments; and patients’ limited financial resources affecting decisions about starting insulin.30,31,39 | Lack of evidence base and clear guidelines; inadequate funding for equipment; workload; time pressures; staffing levels, language skills, and roles (for example, nurse educators); patient support; availability of interpreters; lack of same-physician continuity of care; access to and communication with specialist teams; the need for protocols; and advantages of primary care management.30,33,39,42–44,56–59 | |

| Cholesterol control | – | – | Lack of structured approach to diabetes management.38 | |

| Blood pressure | – | Patients’ financial situation and occupational constraints acting as a barrier to care.36 | Workload and time pressures, preferences of paper-based systems, and inadequate financial compensation.36,60 | |

|

| ||||

| Knowledge (extracts in Knowledge domain with * also coded to Skills domain) | General | Lack of knowledge in self and among colleagues about causes, evidence base, guidelines, services, required lifestyle changes, patient self-management education and cultural beliefs; clinician-education as facilitator of care; and nurses seen as more up to date.32,40,42,44*,46*,47*,48,50,53,61* | Clinician–patient education gap with patients’ knowledge deficits leading to non-compliance coupled with concern about information overload and whether education effective.35,42,45,46*,48,49*,51 | – |

| Glycaemic control | Initiating insulin seen as a simple process by some; clinician confidence and uncertainty in how to initiate insulin; inaccurate beliefs about self-monitoring; and limited familiarity/uncertainty with guideline recommendations.32*,33,39*,41,42*,43*,47*,59* | Limited knowledge of: self-testing; insulin use; erectile dysfunction on insulin; age when insulin required; and long-term effects of diabetes.26,33,39*,41,58 | – | |

| Cholesterol control | Insufficient knowledge of guideline recommendations.38 | Insufficient knowledge leading to discontinuation of medicine.38 | – | |

| Blood pressure | – | Level of understanding affecting amount of information given about BP control.35,36 | – | |

|

| ||||

| Social/professional role and identity | General | Need for greater team working and engagement with diabetes strategies; emphasis on nurses’ role and clarity about responsibilities; and professionalism as an internal drive.32,34,37,42,45,49,51,55,62 | Taking responsibility for managing diabetes balanced with expediency of a paternalistic approach.45–47 | Problems of coordination between professionals’ and nurses’ existing multiple responsibilities.40,48 |

| Glycaemic control | Nurses as complementary to physicians’ role; concern as to where responsibility lay; diabetes care as part of an ongoing relationship with the patient; closer liaison with secondary care a solution.42,58,60 | Sometimes reluctant but empowered by greater involvement in their diabetes care; finding insulin treatment socially embarrassing.41,44,58 | – | |

| Cholesterol control | Lack of perceived responsibility; secondary care’s role.38 | – | – | |

| Blood pressure | Role of other primary care professionals and patients in BP target decisions.35 | – | – | |

|

| ||||

| Emotion | General | Frustration at patients’ compliance levels and prognosis uncertainty/timeframe, and using scare tactics with patients.32,37,40,42,45–47,58,61 | Depression, anxiety, and fear barriers to self-management, although emotional response can be an opportunity for behaviour change.32,37,47 | Feeling overwhelmed by workload and guidelines, and frustrated when secondary care transfer patients with drugs that cannot be prescribed within primary care.32,47,48,62 |

| Glycaemic control | Feeling overwhelmed by the clinical picture; preventing burnout by partnership working; fear of inducing hypoglycaemia; frustration with: the complexity of regimens, poor control of those with different ethnic backgrounds, and limited evidence base for older people.33,39,42,57,59 | Fear of needles, weight gain, and hypoglycaemia with insulin, and with the connotations of ‘drastic’ measures.30,33,39,41,42 | – | |

| Cholesterol control | Frustration at patients’ non-compliance and fears about medication side effects.38 | – | – | |

| Blood pressure | Perceived reward of controlling BP.36 | Life stresses taking priority over diabetes control and causing anxiety when discussing BP monitoring or control.35,36,60 | – | |

|

| ||||

| Beliefs about consequences | General | Pros/cons of tailored medication intensification; the centrality of the clinician– patient relationship, including patient education.37,40,42,46,47,50,56,61 | Cultural beliefs affecting treatment decisions; non-compliance due to complexity or pain; yet motivated by significant changes in management; and opportunistic diabetes care seen as a dismissal of patients’ primary complaint.32,40,47,48,50,52 | – |

| Glycaemic control | Concerns around: older patients’ response to medication; urine testing; and starting insulin, although some advantages recognised; physicians’ beliefs about consequences of diabetes shaped by medical school exposure.33,41–43,39,58,61 | Lack of appreciation of effects of poor control; belief that diet and exercise changes would suffice; compliance issues with medication intensification; belief that insulin could cause complications; and faith in traditional remedies.30,33,39,58,61 | – | |

| Cholesterol control | Concerns about side effects of medication.38 | Reluctance to start medication due to side effects.38 | – | |

| Blood pressure | ‘Vigorous’ guidelines encourage more aggressive management.36 | Resistance to taking additional medication if out-of-clinic BP readings lower than in clinic.60 | – | |

|

| ||||

| Skills (extracts in Knowledge domain with * also coded to Skills domain) | General | Importance of interpersonal skills facilitating holistic care, good communication, and behaviour change skills, although can be a mismatch between training and real-life practice.32,34,37,40,45,46,52,54 | – | – |

| Glycaemic control | Ability to maintain skills in insulin conversion.43 | Patients’ ability to self-care influencing clinicians’ decisions whether to initiate insulin.31 | – | |

| Blood pressure | – | Those with poor technical skills could struggle with telemedicine.60 | – | |

|

| ||||

| Social influences | General | The ‘superior’ specialist having a different message for the patient.45 | Influence of family and cultural beliefs, and specific problems with hard-to-reach or isolated groups.32,37,42,45,47,48,51 | Increased attention to diabetes in health care and the media but a lack of public health campaigns to highlight the seriousness of the condition.40,51 |

| Glycaemic control | Perceived pressure to take on the responsibility for converting patients to insulin; nurses struggling to achieve external legitimacy in insulin initiation.43,59 | Community and spiritual/religious beliefs affecting views about insulin.30,44 | – | |

|

| ||||

| Beliefs about capabilities | General | Variation in abilities to adopt proactive strategies to change patients’ behaviour, circumstances or diabetic control, and low levels of trust in non-physician colleagues’ abilities.32,37,40,45,48,53 | Reliance on medication rather than lifestyle modification.45 | – |

| Glycaemic control | Relative inexperience and lack of confidence prescribing insulin; nurses better at guideline adherence.30,33,39,43 | Concern that those with impairments or older people could find complicated regimens difficult.33,42 | – | |

|

| ||||

| Reinforcement | General | Collegial support to improve treatment in difficult patients and not wanting to ‘nag’ patients.45,46 | Physical disability and lack of immediate response to treatment affecting engagement; patient compliance affected only by major adverse events.32,40,42 | – |

| Glycaemic control | Reinforcement of clinical judgements by specialist colleagues and patients’ assessments; referring to specialists about whom there had been positive feedback.33,57 | Symptom improvement and emphasising the value of treatment to reinforce practice.33,44 | Incentive payments for insulin initiation.59 | |

| Blood pressure | Using raised BP readings to reinforce lifestyle advice.35 | – | – | |

|

| ||||

| Intentions | General | Compliance, avoidance of complications, and professional conscience as motivators.34,49,50 | Non-compliance with diet or treatment despite awareness of consequences.42,47 | – |

| Glycaemic control | – | Non-compliance with dietary practices except before clinic visits.48 | – | |

| Cholesterol control | – | Medication ‘intentional non-compliance’.38 | – | |

| Blood pressure | – | Non-compliance related to personal attitude to diabetes.36 | – | |

|

| ||||

| Behavioural regulation | General | Visual prompts; self-management education; reluctance to ‘nag’; and getting used to developments in care.32,42,45,51 | Challenge of being disciplined to achieve good diabetic control.42 | – |

| Glycaemic control | – | Insulin dose changes following self-monitoring and selective timing of adherence to diet.41,48 | – | |

| Blood pressure | – | – | Immediate feedback to patients with telemedicine systems.60 | |

|

| ||||

| Optimism | General | Feeling positive about preventing complications by early intervention.46 | Lack of a positive approach to self-care and minimising the condition, particularly if asymptomatic.37,45,47 | – |

| Cholesterol control | Near-target lipid achievement believed to be adequate for some patients.38 | – | – | |

|

| ||||

| Memory, attention, and decision processes | General | Using memory rather than guidelines to determine care needs but problems remembering and danger of overloading patients with information.45,52 | Delayed decisions by patients to start insulin due to perceived conflicting information from peers, the media, and healthcare professionals; being unable to sustain lifestyle changes once a lifestyle programme has ended.30,51 | – |

| Glycaemic control | Collusion with patients to avoid starting insulin.42 | – | – | |

|

| ||||

| Goals | General | The need to prioritise care processes and individualise goals for the patient.46,52 | Patients’ lack of ambition, interest, and engagement.62 | – |

| Glycaemic control | Converting patient to insulin allowing nurses to ‘see[ing] the job through’.43 | – | – | |

BP = blood pressure. Note: clinical targets extracts coded to: general diabetes care; glycaemic control; cholesterol control; BP control; foot exam; smoking; weight management; urine albumin–creatinine ratio/equivalent.

Environmental context and resources

Clinicians consistently describe limited resources or environmental constraints as barriers, especially in relation to achieving glycaemic control or general aspects of care. Large workload and resulting time pressures undermine clinicians’ abilities to deliver care to their own satisfaction:

‘It is a burden on one doctor to see 30 or more patients, we had to do a lot of things to each patient in addition to documentation of the findings in the computer.’

(Physician)32

Clinicians express concern about the resources available, including for patient education, given rising demand and expectations:

‘The huge thing, which is raising its head already and will in the future, is the enormous burden of people with diabetes. The ever-increasing demand to reach tighter and tighter guidelines, and the limited resources available to help us do that …’

(Physician)33

Given the increased number of patients managed in primary care, specialists can play an important guiding role, although communication is not always optimal:

‘I generally tell people that once they have been to see a specialist that they come back and see me afterwards and tell me what happened, that’s my way of finding out. And we obviously get letters which are quite often not actually of sufficient depth to be of much use to us.’

(Physician)34

A wide range of organisation-level factors affect care, such as the availability of information technology and protocols to structure diabetes care, lack of personal continuity of care, and limited continuing education opportunities for clinicians (Table 1).

Clinicians also recognised patients’ socioeconomic and occupational circumstances as significant problems, especially in enabling self-management:

‘You know, if they’re not in very good housing … they’ve perhaps got young children or if life’s stacked against them anyway, then I don’t think they’re as able to make the [suggested lifestyle] changes.’

(Nurse)35

‘The minute people are on shift work, it’s really hard for them to control everything, from remembering to take their pills when they’re home and when they’re not, when they’re at work and when they’re not.’

(Physician)36

They also acknowledged limitations imposed by comorbidities:

‘It’s become something ... of a spiral here ... [arthritis] has reduced his ability to exercise, which has made his weight go up, which has made his diabetic control worse.’

(Physician)37

Such factors, often outside of patients’ and clinicians’ loci of control, collectively engender helplessness in the face of immutable adversity.

Knowledge and skills

Limited knowledge and skills among patients and clinicians hinder achievement of glycaemic, cholesterol, and blood pressure goals. Physicians find it difficult to recall or keep up with changing recommendations.38 Clinicians lacked confidence in treatment intensification, especially when considering insulin:

‘There’s not always somebody to ask [for advice] and there’s no protocol, so the easiest thing is to just send [the patient] to the hospital ... and let them make the decision for you [about starting insulin].’

(Physician)39

Clinicians recognise the importance of supporting changes in patient behaviour but lack effective strategies:

‘… there are some patients that I just can’t get to make changes, despite my best efforts.’

(Physician)37

‘Providers complained that they had received insufficient training in medical school and in their residencies to promote behavioural change … As one physician noted, most providers can treat conditions that require only medications pretty well, but “not many give good advice for diabetes”.’40

Clinicians recognised that patients often need a lot of support to adhere to self-management plans:

‘One client was documenting “error” every time [the blood glucose] meter said error … no one had explained this meant error with machine/strip.’

(Nurse)41

‘… people don’t understand blood pressure. I don’t think they really understand what we’re [trying to do].’

(Nurse)35

Therefore, clinicians consider patient education important but are concerned about overloading patients with information and doubt the effects of lifestyle counselling.

Professional role and identity

Nurses’ and physicians’ roles have evolved as diabetes care has become integrated into primary care, with nurses playing a central role.42 However, both physicians and nurses express uncertainty or disagreement over who is responsible for various elements of patient care across both primary and secondary care:

‘… ambiguity about who was responsible for managing diabetes care contributed to difficulty coordinating care with other providers such as pharmacists, diabetes educators, and endocrinologists.’

(Physicians)37

‘The fact that insulin conversion involves setting dosage levels seemed to be at the root of [nurses’] concern [about accountability], and this was perceived as a major shift in responsibility … “I think we’ve got to recognise the level of responsibility and the GPs have got to recognise that and pay us appropriately”.’

(Nurse)43

Clinicians also harbour doubts over how ready patients are to embrace self-management roles.41,44 Some physicians subsequently feel that a more physician-centred approach is justified by patient preferences, expediency, or pressures to improve outcomes:

‘GPs often become directing and paternalistic in order to cope more easily [with barriers to care].’

(Physicians)45

Emotion

Clinicians experience a range of often negative emotions in dealing with diabetes, especially around patient compliance to management plans or adverse effects of treatment, and employ varying approaches to dealing with emotions in patient care. They become frustrated at patients’ compliance to advice:

‘We just give them the medicine ... and the next time they come in we ask them if they’ve taken it and they say “No”. That frustrates us [because] ... the patient doesn’t want to change for the better.’

(Physician)37

Clinicians also have concerns about treatment side effects:

‘Fear of side effects … also mentioned as reasons not to start lipid-lowering medication at that moment.’

(Physicians)38

‘… reluctant to initiate treatment, fearing that it would induce hypoglycaemia in the patient.’

(Physicians)39

However, success is professionally rewarding:

‘These miraculous patients, who had followed their doctor’s orders in [sic] the letter, served as a relief [to the GPs].’

(Physicians)46

Some physicians admit to exploiting emotions as leverage to change patients’ behaviour, including patients’ initial anxiety at diagnosis:

‘Some doctors mentioned that they expressed aggression towards the non-adherent patients and sometimes they frightened them with the potential complications of diabetes.’

(Physicians)32

‘When people are feeling more anxious about their disease they’re more likely to want to absorb information and make health changes around their lifestyle.’

(Physician)47

Clinicians recounted patients’ fears of needles and hypoglycaemia when discussing insulin, but also used the threat of insulin as a way of signalling the need for major change:

‘The very words “needle” or “injection” carried complex connotations and, sometimes, the suggestion of starting insulin could signify a message of failure in other therapies to the patient, that is, that “drastic” measures were now needed.’

(Physicians)33

Other domains

Beliefs about consequences, social influences, and (lack of) reinforcement emerged as further key influences on treatment targets and general aspects of care. Clinicians recognise that treatment intensification can cause more harm than good, particularly in older patients.42 Wider social influences also feature in several studies, including family, community, and cultural beliefs:

‘I think they [patients] were thinking that the insulin is from, what do you call this, non-halal (“lawful”) ... products.’

(Physician)30

Clinicians recognise the lack of reinforcement through delayed responses to treatment and patients’ tendencies to minimise their condition:

‘… it is easier to modify treatments in conditions with definite symptoms and more gratifying when treatments provide immediate relief, neither of which applies to diabetes.’

(Physicians and nurses)40

‘ [Physicians] also remarked that diabetes patients tend to minimise their disease. This really is in contrast with the GP’s objectives.45

One study notably suggested collusion to avoid insulin initiation:

‘ [Patients] see [starting insulin] as being their point of failure almost. I think that some patients can be very persuasive to us to let you say you don’t want me on insulin. The patients don’t want to go on it. So there is a joint tendency that they don’t go on it.’

(Physician or nurse — unspecified)42

Robustness of findings

Most included studies scored favourably on the NICE study quality checklist (details available from the authors on request). The role of the researcher and methods and analysis were often inadequately reported to allow reliable judgements.

DISCUSSION

Summary

Primary care clinicians face multiple challenges in the inherently complex management of diabetes. They struggle to meet evolving treatment targets within limited time and resources, and express frustrations with resulting compromises in care. Clinicians lack confidence in their knowledge of guidelines and skills in particular tasks, such as initiating insulin and facilitating patient behaviour change. Despite continuing policy drives to promote self-management, clinicians often find it hard to share responsibility effectively with patients and support behaviour change. Changing role boundaries, between primary and secondary care, and also between physicians and nurses within primary care, have generated uncertainty and unease about where clinical responsibility resides. Many accounts were couched in emotional terms, especially frustrations over patient compliance with treatment and anxieties about treatment intensification.

Strengths and limitations

This study has six main limitations. First, perceived may differ from actual barriers and enablers. Nevertheless, quality improvement strategies specifically need to target such perceptions; these may be more amenable to change than major resource and structural constraints.63 Second, review findings depend on the methods of included studies; possible under-reporting was noted within certain domains. For example, given that diabetes is a complex, multifaceted condition for both clinicians and patients to manage, it is surprising that problems with memory and attention processes emerged relatively infrequently. This may be due to under-detection in the original studies or such factors simply being less important. Third, grey and non-English language literature was not included. However, checks of reference lists of included studies suggested that most relevant studies had been identified. Fourth, most studies were from the US or the UK; the findings could therefore over-represent clinician experience from these territories. However, similar themes were found in studies spanning the Middle and Far East, and other European countries, suggesting that many factors are universal. Fifth, qualitative systematic review methods are still evolving, with variable approaches to evidence synthesis.64 This study used an explicit framework to organise the findings,26 and followed reporting guidance.65 Sixth, although first-hand patient perspectives were not examined, the study focused specifically on what clinicians believe about patient influences on care.

Comparison with existing literature

Understanding clinicians’ beliefs is critical in designing more effective improvement strategies. This study drew on an organising framework to identify environmental and behavioural influences potentially amenable to change through linked behaviour change techniques.66–68 An additional 12 studies were found that were published after an earlier review.69 Although uncertainty about professional roles and clinical responsibility was also identified, several key barriers notably persist, suggesting limited progress over recent years to address recognised barriers to care. In contrast with a review of patient perspectives suggesting preferences for achieving glycaemic control over minor hypoglycaemic events,70 this study found that clinicians reported significant fears among both patients and clinicians around inducing hypoglycaemia.

The clinical management of type 2 diabetes is evolving and becoming more structured. Tricco and colleagues’ meta-analysis of randomised trials14 suggests that quality improvement focusing on systematic chronic disease management and patient involvement is particularly effective in achieving treatment goals.11 The findings, especially those indicating time constraints and uncertainties in professional roles and responsibility, suggest that much scope still exists for improving the organisation of care, even within better developed primary care systems. Significant progress here is likely to depend on concerted action across different levels of healthcare systems.71 Tricco and colleagues also found that interventions solely targeting clinicians, such as education or feedback of performance data, appeared less effective.14 However, the rationales and behaviour change techniques underpinning such interventions are often poorly developed and described, limiting cumulative learning that can enhance effects.72,73 A range of modifiable clinician perceptions that behaviour change strategies could target more effectively were identified, such as belief in self-efficacy around initiating insulin and facilitating patient behaviour change.

Implications for research and practice

There is clearly a challenge around addressing clinicians’ pessimism around patient behaviour change. Some of this pessimism is understandable given the limited impacts of structured patient education programmes.74 Such policies are unlikely to bear fruit if clinicians have nihilistic attitudes and lack training in behavioural approaches. This study found that emotional factors repeatedly featured in clinicians’ accounts, consistent with studies highlighting emotional influences on other professional behaviours.75,76 Both clinicians and patients express anxiety and uncertainty about how best to manage diabetes. Clinicians further recognise that both they and patients can suffer from information overload. Rationalist approaches based largely on improving knowledge about the technical aspects of care are likely to have a limited impact on professional behaviour and patient outcomes. Therefore, future research to improve the delivery of diabetes care could focus on equipping clinicians with skills of facilitating behaviour change while managing engendered emotions.

Some barriers to recommended care varied according to the treatment goal. Different clinical behaviours and targets require different intervention approaches rather than a ‘one size fits all’ approach.77 However, it is possible to incorporate a range of behaviour change techniques within implementation interventions commonly used in primary care, such as computerised prompts or audit and feedback.78 Improvement strategies should also address both organisational and individual levels, for example, clarifying primary care team roles and responsibilities, and training clinicians to support patient behaviour change, respectively.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Judy Wright for assistance with constructing searches and Ian McDermott for helpful comments on an earlier draft. Wendy Hobson kindly assisted with references and table formatting.

Appendix 1. Summary of included studies

| Study and year published (continent) | Study aims | Data collection method | Inclusion criteria | Participants | Clinical targets studied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee30 2012 (Asia) Note: Lee 2012 and Lee 2014 report different data from the same study | To identify barriers to insulin initiation from the healthcare professionals’ perspective | Focus groups and interviews | Healthcare professionals providing diabetes care and involved in insulin initiation in 3 primary care healthcare settings in Malaysia | 38 healthcare professionals, 28 of whom were identified as primary care physicians | Glycaemic control: initiation of insulin |

| Lee31 2014 (Asia) Note: Lee 2012 and Lee 2014 report different data from the same study | To explore how healthcare professionals assess patients when initiating insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes | Semi-structured interviews and focus groups | Healthcare professionals and other stakeholders who were involved in insulin initiation in primary and secondary care | 36 healthcare professionals (12 family physicians; 10 family medicine specialists; 8 medical officers; 3 diabetes nurse educators; 2 endocrinologists; 1 pharmacist); and 5 government policymakers. | Glycaemic control: initiation of insulin |

| Greaves43 2003 (Europe; UK) | To explore the views of primary care nurses about converting patients with diabetes from oral hyperglycaemic [sic] agents to injected insulin within primary care | Semi-structured interviews | Primary care nurses with responsibility for diabetes care | 25 primary care nurses, 18 of these from a diabetes special interest group. Years qualified 27.2 (SD 6.8; range 13–39); years as practice nurse 12 (5.8; 4–25) | Glycaemic control: initiation of insulin |

| Noor Abdulhadi32 2013 (Asia) | To explore primary healthcare providers’ experience of encounters with patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and their preferences and suggestions for future improvement of diabetes care | Semi-structured interviews | Primary care physicians and nurses working at a primary healthcare centre who had participated in an observational study | 19 primary care physicians and 7 primary care nurses; age range 25–55 years | General |

| Agarwal33 2008 (North America) | To explore the process and rationale for prescribing decisions of primary care physicians when treating older patients with type 2 diabetes | Interviews | Primary care physicians actively practising within a 1-hour drive of a large suburban city in Ontario, Canada | 21 primary care physicians | Glycaemic control: prescribing insulin |

| Pooley34 2001 (Europe; UK) | To explore the issues that patients and doctors perceive as central to effective management of diabetes with particular attention to the nature of the patient–practitioner relationship | Interviews | Health professionals: from 4 localities within 2 health authorities in North West England, UK, who had signalled their willingness to participate on a previous questionnaire | Healthcare professionals: 7 primary care physicians, 9 primary care nurses, 9 diabetes nurse specialists, 3 community nurses, 5 dieticians, 4 chiropodists, 3 optometrists, 2 diabetes specialist physicians | General |

| Brown47 2002 (North America) | To explore primary care physicians’ perceptions of the barriers and facilitators to the management of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus | Focus groups | Primary care physicians participating in simultaneous quantitative study on the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus | 30 primary care physicians; age not recorded but average years since graduation 18.7 (range 4–35); sex (M:F) 16:14 | General |

| Stewart35 2006 (Europe; UK) | To explore whether and how practice nurses discuss blood pressure targets and beliefs about the barriers to achieving target blood pressure in patients with diabetes | Semi-structured interviews | Primary care nurses responsible for providing most of the diabetes care in practices taking part in a trial to improve blood pressure in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in Nottingham, UK | 43 primary care nurses | Blood pressure |

| Howard36 2006 (North America) | To investigate the factors that influence the management of hypertension in patients with type 2 diabetes | Interviews (for qualitative element) | Physicians and patients from 2 primary care medical centres in Halifax, Canada | 5 primary care physicians (and 7 patients) | Blood pressure |

| Crosson37 2010 (North America) | To explore what primary care physicians perceive to be barriers to good cardiovascular disease risk factor control in those with diabetes and hypertension and high cholesterol | Interviews | Primary care physicians in 4 states in US caring for patients with diabetes in a variety of practice environments (solo, group practice, integrated healthcare delivery system) | 34 primary care physicians | General: with an interest in cardiovascular disease risk factor control |

| Ab38 2009 (Europe; non-UK) | To determine factors underlying primary care physicians’ decisions not to prescribe lipid-lowering drugs to patients with type 2 diabetes | Semi-structured interviews | Primary care physicians in a region of the north of the Netherlands, where a guideline on the use of statins in diabetes had been distributed, who indicated they were familiar with the guideline | 7 primary care physicians | Cholesterol control: prescribing lipid-lowering drugs |

| Haque39 2005 (Africa) | To examine barriers to initiating insulin therapy in patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes on maximum oral glucose-lowering agents | Focus groups and semi-structured interviews | Primary care physicians at one community health centre in the Western Cape | 46 primary care physicians working at 4 primary care community health centres in Cape Town district | Glycaemic control: initiation of insulin |

| Larme40 1998 (North America) | To explore how attitudes rather than knowledge may impede primary care providers’ adherence to standards of care in diabetes | Interviews (for qualitative element) | Primary care providers attending a continuing medical education programme on diabetes | 31 healthcare professionals: 24 primary care physicians, 2 primary care nurses, and 5 physician assistants; age range 27–58 years; sex (M:F) 23:8 | General |

| Fhärm46 2009 (Europe; non-UK) | To explore primary care physicians’ experiences regarding treatment practice in type 2 diabetes with specific focus on the prevention of cardiovascular disease | Focus groups | Experienced primary care physicians from the County of Västerbotten, Sweden, with patients with type 2 diabetes in their practice | 14 primary care physicians from 9 group practices; sex (M:F) 6:8; age median 54 years, range 43–64; years since medical degree 24 (10–36); rural:urban practice 5:9 | General: with an interest in the prevention of cardiovascular disease |

| Abbott41 2007 (Europe; UK) | To examine the perceived purposes and functions of self-testing (self-monitoring of blood glucose) as understood by nurses who treat/manage type 2 diabetes in primary care settings | Semi-structured interviews | Nurses working in community and primary care in Essex, UK | 7 nurses | Glycaemic control: self-monitoring of blood glucose |

| Jeavons42 2006 (Europe; UK) | To investigate doctors' and nurses' views about treating patients with type 2 diabetes with unacceptable glycaemic control receiving maximal oral treatment | Focus groups | One primary care physician from each practice in the local health authority; all primary care physician trainers with the local training scheme; and one practice nurse from each practice attending meetings as part of a local practice nurse support group | 15 primary care physicians, 8 primary care nurses. Years qualified: physicians 12–41; nurses 6–28. Sex: physicians (M:F) 11:4; nurses 0:8 | Glycaemic control: initiation of insulin |

| Wens45 2005 (Europe; non-UK) | To identify primary care physicians’ thoughts and feelings about type 2 diabetes patients’ adherence to treatment | Focus groups | All primary care physicians in one Belgian municipality | 40 primary care physicians; mean age 45.3 years (10.5 SD); sex (M:F) 26:14 | General |

| Burden44 2007 (Europe; UK) | To measure the attitudes of patients, primary care physicians, and nurses when starting insulin in people with type 2 diabetes in primary care | Focus groups followed by plenary session and interviews | For qualitative element: primary care physicians and nurses in two cohorts who completed the Insulin for Life training course on initiating insulin | 37 primary care physicians and nurses (numbers of each not specified) | Glycaemic control: initiation of insulin |

| Alberti49 2007 (Africa) | To discover the main barriers and facilitators to care in the management of diabetes in primary care in a low/middle income country | Observation, focus groups, and interviews | Health professionals (including physicians and nurses) providing diabetes care in public sector primary care centres in Tunisia and patients with diabetes | 3 health centres: staff and patients (observation); lead physician plus 7 key informants (interview); 4 paramedical staff groups and 12 patient groups (focus groups); also visits to 48 other health centres; attendees at 19 meetings; and discussions with staff in government departments | General |

| Daniels48 2000 (Africa) | To audit the responses of health professionals in primary care to receipt of diabetes and hypertension guidelines and to determine their attitudes to implementation | Focus groups and in-depth discussions at first site; semi-structured interviews at other 3 sites; and clinical observation at 3 sites | Healthcare professionals working at community health centres in the Western Cape | 15 physicians and 10 nurses at 4 community health centres | General |

| Grant50 2009 (North America) | To assess whether patient or physician demographic variables influence the decision to intensify therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes | Structured interviews (for qualitative element of study) | Primary care physicians active in clinical care more than half the time and practising in New Jersey, New York, or Pennsylvania, with 12 years or 22 years clinical experience and trained in accredited US medical schools | 192 primary care physicians | General: with an interest in medication intensification |

| Halifax60 2007 (North America) | To review telemedicine as it pertains to hypertension management and to outline experiences in developing a new telemedicine system | Focus groups | Primary care physicians with active clinical practice with English-speaking patients who had type 2 diabetes and hypertension | 24 primary care physicians | Blood pressure |

| Kern52 2001 (North America) | To explore primary care providers' perceived barriers to the delivery of diabetes care | Semi-structured interviews | Primary care physicians from practices with a relatively high proportion of patients with diabetes | 12 primary care physicians | General |

| Kirsh62 2010 (North America) | To identify best practices in outpatient diabetes and the factors associated with their development | Telephone interviews | Primary care diabetes clinic sites | One or more informant/s from each of 31 sites: primary care clinic directors; primary care physicians and nurse practitioners; nurse managers; and clinical pharmacists | General |

| Loewe61 2000 (North America) | To explore the different frames or explanatory models that physicians and patients use to understand diabetes | Semi-structured interviews and participant observation | Healthcare professionals and patients with diabetes at 1 of 2 family practice training sites in Chicago, US | 17 healthcare professionals: 12 primary care physicians; others: 1 medical student, 1 physician assistant, 3 attending physicians (and 22 patients with diabetes) | General |

| Raaijmakers51 2013 (Europe; non-UK) | To investigate the facilitating and impeding factors among healthcare professionals in diabetes care | Semi-structured interviews | Healthcare professionals with a primary role in diabetes care | 18 healthcare professionals in total comprising: 3 primary care physicians, 3 primary care nurses, 1 primary care diabetes nurse (others: non-primary care diabetes nurse, dieticians, physical therapists, internal medicine physicians, pharmacist). Of all 18: mean age 44 years (range 31–59); sex (M:F) 7:11 | General |

| Trewin56 1999 (Europe; UK) | To investigate a suite of presumed influences on primary care physician prescribing practice | Structured interviews | Primary care physicians working in Devon in UK | 20 primary care physicians | Glycaemic control |

| Manski-Nankervis57 2014 (Australia and Oceania) | To explore roles and relationships between health professionals involved in insulin initiation | Interviews (face-to-face and by telephone) | Purposely selected from responders to previous survey in Australia in which relational coordination between health professionals involved in insulin initiation was measured | 21 healthcare professionals: 5 primary care physicians; 5 primary care nurses; 5 diabetes nurse educators; 6 hospital physicians | Glycaemic control: initiation of insulin |

| Tan58 2011 (Asia) | To determine the issues relating to insulin initiation for patients with diabetes managed in primary care polyclinics in Singapore | Focus groups | Physicians and nurses working in primary care polyclinics in Singapore and patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus | 8 physicians; 10 nurses; and 11 patients | Glycaemic control: initiation of insulin |

| Furler59 2011 (Australia and Oceania) | To explore the views of family physicians, diabetes nurse educators, and patients about starting insulin in primary care | Semi-structured interviews | Primary care physicians, diabetes nurse educators with experience of primary care, and patients who had recently commenced insulin or on maximum oral therapy | 10 family physicians; 4 diabetes nurse educators; and 12 patients | Glycaemic control: initiation of insulin |

| Elliott53 2011 (North America) | To identify the systemic barriers to primary care diabetes management in the small office setting in Delaware | Focus groups | Primary care physicians in Delaware | 25 physicians: 21 primary care physicians and 4 specialists with an interest in primary care management of diabetes | General |

| O’Connor54 2013 (Europe; non-UK) | To explore family physicians’ and practice nurses’ perceptions of barriers and facilitators to the proposed transfer of diabetes care to general practice | Focus groups | Practising family physicians and practice nurses in Limerick city and county in Ireland | 55 family physicians and 11 practice nurses | General |

| McHugh55 2013 (Europe; non-UK) | To examine the barriers to, and facilitators in, improving diabetes management from the general practice perspective | Interviews | Family physicians working in Ireland who had opted in during a preceding postal survey on the organisation of diabetes care | 31 family physicians | General |

Funding

This study is the independent work of the authors. Bruno Rushforth was funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) In-Practice Fellowship while undertaking the systematic review. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health.

Ethical approval

Not required.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization . 2008–2013 Action plan for the global strategy for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: WHO; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diabetes UK . State of the nation 2013 England. London: Diabetes UK; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization Diabetes programme. http://www.who.int/diabetes/en/ (accessed 5 Nov 2015).

- 4.Goldney RD, Phillips PJ, Fisher LJ, Wilson DH. Diabetes, depression, and quality of life: a population study. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(5):1066–1070. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Depression in adults with a chronic physical health problem: recognition and management CG91. London: NICE; 2009. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg91/ (accessed 5 Nov 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carney RM, Freedland KE, Miller GE, Jaffe AS. Depression as a risk factor for cardiac mortality and morbidity: a review of potential mechanisms. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(4):897–902. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hex N, Bartlett C, Wright D, et al. Estimating the current and future costs of Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes in the UK, including direct health costs and indirect societal and productivity costs. Diabet Med. 2012;29(7):855–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Type 2 diabetes: the management of type 2 diabetes CG87. London: NICE; 2009. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg87 (accessed 5 Nov 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes 2014. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(Suppl 1):S14–S80. doi: 10.2337/dc14-S014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization . Prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases: guidelines for primary health care in low-resource settings. Geneva: WHO; 2012. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/76173/1/9789241548397_eng.pdf (accessed 5 Nov 2015). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Health and Social Care Information Centre . National Diabetes Audit 2012–2013 report 1: care processes and treatment targets. Leeds: HSCIC; 2014. http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB14970 (accessed 5 Nov 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002;288(14):1775–1779. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith S, Bury G, O’Leary M, et al. The North Dublin randomized controlled trial of structured diabetes shared care. Fam Pract. 2004;21(1):39–45. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tricco AC, Ivers NM, Grimshaw JM, et al. Effectiveness of quality improvement strategies on the management of diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9833):2252–2261. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60480-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grol R. Personal paper. Beliefs and evidence in changing clinical practice. BMJ. 1997;315(7105):418–421. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7105.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker R, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Gillies C, et al. Tailored interventions to overcome identified barriers to change: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(3):CD005470. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005470.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dietrich UC. Factors influencing the attitudes held by women with type II diabetes: a qualitative study. Patient Educ Couns. 1996;29(1):13–23. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(96)00930-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holmström IM, Rosenqvist U. Misunderstandings about illness and treatment among patients with type 2 diabetes. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49(2):146–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hunt LM, Valenzuela MA, Pugh JA. NIDDM patients’ fears and hopes about insulin therapy. The basis of patient reluctance. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(3):292–298. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.3.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai WA, Lew-Ting CY, Chie WC. How diabetic patients think about and manage their illness in Taiwan. Diabet Med. 2005;22(3):286–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawton J, Peel E, Parry O, et al. Lay perceptions of type 2 diabetes in Scotland: bringing health services back in. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(7):1423–1435. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.NHS NHS atlas of variation in healthcare. 2011. http://www.rightcare.nhs.uk/index.php/nhs-atlas/ (accessed 5 Nov 2015).

- 23.Shaw RL, Booth A, Sutton AJ, et al. Finding qualitative research: an evaluation of search strategies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2004;4:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization . WHO expert committee on diabetes mellitus Second report. Geneva: WHO; 1980. Technical Report Series 646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Audit Office The management of adult diabetes services in the NHS. 2012 http://www.nao.org.uk/publications/1213/adult_diabetes_services.aspx (accessed 5 Nov 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7:37. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, et al. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(1):26–33. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.011155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tavender EJ, Bosch M, Gruen RL, et al. Understanding practice: the factors that influence management of mild traumatic brain injury in the emergency department — a qualitative study using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implement Sci. 2014;9:8. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-9-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . The guidelines manual. January 2009. Appendix I: methodology checklist: qualitative studies. London: NICE; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee YK, Lee PY, Ng CJ. A qualitative study on healthcare professionals’ perceived barriers to insulin initiation in a multi-ethnic population. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-13-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee PY, Lee YK, Khoo EM, Ng CJ. How do health care professionals assess patients when initiating insulin therapy? A qualitative study. Prim Care Diabetes. 2014;8(1):49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noor Abdulhadi NM, Al-Shafaee MA, Wahlström R, Hjelm K. Doctors’ and nurses’ views on patient care for type 2 diabetes: an interview study in primary health care in Oman. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2013;14(3):258–269. doi: 10.1017/S146342361200062X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agarwal G, Nair K, Cosby J, et al. GPs’ approach to insulin prescribing in older patients: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58(553):569–575. doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X319639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pooley CG, Gerrard C, Hollis S, et al. ‘Oh it’s a wonderful practice … you can talk to them’: a qualitative study of patients’ and health professionals’ views on the management of type 2 diabetes. Health Soc Care Community. 2001;9(5):318–326. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2524.2001.00307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stewart J, Dyas J, Brown K, Kendrick D. Achieving blood pressure targets: lessons from a study with practice nurses. J Diabetes Nurs. 2006;10(5):186–193. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Howard JA, Bower K, Putnam W. Factors influencing the management of hypertension in type 2 diabetes. Can J Diabetes. 2006;30(1):38–45. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crosson JC, Heisler M, Subramanian U, et al. Physicians’ perceptions of barriers to cardiovascular disease risk factor control among patients with diabetes: results from the translating research into action for diabetes (TRIAD) study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(2):171–178. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2010.02.090125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ab E, Denig P, van Vliet T, Dekker JH. Reasons of general practitioners for not prescribing lipid-lowering medication to patients with diabetes: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2009;10:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-10-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haque M, Emerson SH, Dennison CR, et al. Barriers to initiating insulin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in public-sector primary health care centres in Cape Town. S Afr Med J. 2005;95(10):798–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Larme AC, Pugh JA. Attitudes of primary care providers toward diabetes: barriers to guideline implementation. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(9):1391–1396. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.9.1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abbott S, Burns J, Gleadell A, Gunnell C. Community nurses and self-management of blood glucose. Br J Community Nurs. 2007;12(1):6–11. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2007.12.Sup3.23781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jeavons D, Hungin AP, Cornford CS. Patients with poorly controlled diabetes in primary care: healthcare clinicians’ beliefs and attitudes. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82(967):347–350. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2005.039545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Greaves CJ, Brown P, Terry RT, et al. Converting to insulin in primary care: an exploration of the needs of practice nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2003;42(5):487–496. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burden ML, Burden AC. Attitudes to starting insulin in primary care. Practical Diabetes International. 2007;24(7):346–350. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wens J, Vermeire E, Van Royen P, et al. GPs’ perspectives of type 2 diabetes patients’ adherence to treatment: a qualitative analysis of barriers and solutions. BMC Fam Pract. 2005;6(1):20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-6-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fhärm E, Rolandsson O, Johansson EE. ‘Aiming for the stars’: GPs’ dilemmas in the prevention of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes patients: focus group interviews. Fam Pract. 2009;26(2):109–114. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmp002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown JB, Harris SB, Webster-Bogaert S, et al. The role of patient, physician and systemic factors in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Fam Pract. 2002;19(4):344–349. doi: 10.1093/fampra/19.4.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Daniels A, Biesma R, Otten J, et al. Ambivalence of primary health care professionals towards the South African guidelines for hypertension and diabetes. S Afr Med J. 2000;90(12):1206–1211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alberti H, Boudriga N, Nabli M. Primary care management of diabetes in a low/middle income country: a multi-method, qualitative study of barriers and facilitators to care. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:63. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grant RW, Lutfey KE, Gerstenberger E, et al. The decision to intensify therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes: results from an experiment using a clinical case vignette. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(5):513–520. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.05.080232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Raaijmakers LG, Hamers FJ, Martens MK, et al. Perceived facilitators and barriers in diabetes care: a qualitative study among health care professionals in the Netherlands. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:114. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kern DH, Mainous AG., 3rd Disease management for diabetes among family physicians and general internists: opportunism or planned care? Fam Med. 2001;33(8):621–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elliott DJ, Robinson EJ, Sanford M, et al. Systemic barriers to diabetes management in primary care: a qualitative analysis of Delaware physicians. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26(4):284–290. doi: 10.1177/1062860610383332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O’Connor R, Mannix M, Mullen J, et al. Structured care of diabetes in general practice: a qualitative study of the barriers and facilitators. Ir Med J. 2013;106(3):77–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McHugh S, O’Mullane M, Perry IJ, Bradley C. Barriers to, and facilitators in, introducing integrated diabetes care in Ireland: a qualitative study of views in general practice. BMJ Open. 2013;3(8):e003217. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Trewin VF, Veitch GB, Lawrence CJ. Influences on GP prescribing habits: any hypoglycaemic for the elderly? Pharm J. 1999;262(7039):482–484. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Manski-Nankervis JA, Furler J, Blackberry I, et al. Roles and relationships between health professionals involved in insulin initiation for people with type 2 diabetes in the general practice setting: a qualitative study drawing on relational coordination theory. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-15-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tan AM, Muthusamy L, Ng CC, et al. Initiation of insulin for type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: what are the issues? A qualitative study. Singapore Med J. 2011;52(11):801–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Furler J, Spitzer O, Young D, Best J. Insulin in general practice: barriers and enablers for timely initiation. Aust Fam Physician. 2011;40(8):617–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Halifax NV, Cafazzo JA, Irvine MJ, et al. Telemanagement of hypertension: a qualitative assessment of patient and physician preferences. Can J Cardiol. 2007;23(7):591–594. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(07)70807-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Loewe R, Freeman J. Interpreting diabetes mellitus: differences between patient and provider models of disease and their implications for clinical practice. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2000;24(4):379–401. doi: 10.1023/a:1005611207687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kirsh S, Hein M, Pogach L, et al. Improving outpatient diabetes care. Am J Med Qual. 2012;27(3):233–240. doi: 10.1177/1062860611418491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grol R, Wensing M, Eccles M, Davis D, editors. Improving patient care: the implementation of change in health care. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Glenton C, Colvin CJ, Carlsen B, et al. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of lay health worker programmes to improve access to maternal and child health: qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(10):CD010414. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010414.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.PRISMA Transparent reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. http://www.prisma-statement.org/ (accessed 5 Jan 2016).

- 66.Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6:42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Michie S, Johnston M, Francis J, et al. From theory to intervention: mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. Applied Psychology. 2008;57(4):660–680. [Google Scholar]

- 68.van Bokhoven MA, Kok G, van der Weijden T. Designing a quality improvement intervention: a systematic approach. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12(3):215–220. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.3.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nam S, Chesla C, Stotts NA, et al. Barriers to diabetes management: patient and provider factors. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;93(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.von Arx LB, Kjaer T. The patient perspective of diabetes care: a systematic review of stated preference research. Patient. 2014;7(3):283–300. doi: 10.1007/s40271-014-0057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ferlie EB, Shortell SM. Improving the quality of health care in the United Kingdom and the United States: a framework for change. Milbank Q. 2001;79(2):281–315. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ivers NM, Sales A, Colquhoun H, et al. No more ‘business as usual’ with audit and feedback interventions: towards an agenda for a reinvigorated intervention. Implement Sci. 2014;9:14. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-9-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Improved Clinical Effectiveness through Behavioural Research Group Designing theoretically-informed implementation interventions. Implement Sci. 2006;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Khunti K, Gray LJ, Skinner T, et al. Effectiveness of a diabetes education and self management programme (DESMOND) for people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus: three year follow-up of a cluster randomised controlled trial in primary care. BMJ. 2012;344:e2333. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dyson J, Lawton R, Jackson C, Cheater F. Does the use of a theoretical approach tell us more about hand hygiene behaviour? The barriers and levers to hand hygiene. J Infect Prev. 2011;12(1):17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 76.McSherry LA, Dombrowski SU, Francis JJ, et al. ‘It’s a can of worms’: understanding primary care practitioners’ behaviours in relation to HPV using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implement Sci. 2012;7:73. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lugtenberg M, Zegers-van Schaick JM, Westert GP, Burgers JS. Why don’t physicians adhere to guideline recommendations in practice? An analysis of barriers among Dutch general practitioners. Implement Sci. 2009;4:54. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Presseau J, Ivers NM, Newham JJ, et al. Using a behaviour change techniques taxonomy to identify active ingredients within trials of implementation interventions for diabetes care. Implement Sci. 2015;10:55. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0248-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]