Abstract

Biochemical communication between the cytoplasmic and mitochondrial subsystems of the cell depends on solute carriers in the mitochondrial inner membrane that transport metabolites between the two compartments. We have expressed and purified a yeast mitochondrial carrier protein (Mtm1p, YGR257cp), originally identified as a manganese ion carrier, for biochemical characterization aimed at resolving its function. High affinity, stoichiometric pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP) cofactor binding was characterized by fluorescence titration and calorimetry, and the biochemical effects of mtm1 gene deletion on yeast mitochondria were investigated. The PLP status of the mitochondrial proteome (the mitochondrial ‘PLP-ome’) was probed by immunoblot analysis of mitochondria isolated from wild type (MTM1+) and knockout (MTM1−) yeast, revealing depletion of mitochondrial PLP in the latter. A direct activity assay of the enzyme catalyzing the first committed step of heme biosynthesis, the PLP-dependent mitochondrial enzyme 5-aminolevulinate synthase, extends these results, providing a specific example of PLP cofactor limitation. Together, these experiments support a role for Mtm1p in mitochondrial PLP trafficking and highlight the link between PLP cofactor transport and iron metabolism, a remarkable illustration of metabolic integration.

Keywords: Mitochondrial carrier protein, Pyridoxal 5′-phosphate, Iron homeostasis, Heme biosynthesis

INTRODUCTION

Mitochondria serve as metabolic engines of the eukaryotic cell [1], important not only for oxidative phosphorylation and central pathways of energy metabolism, but also for diverse biosynthetic processes [2], including synthesis of carbon frameworks, amino acids, membrane phospholipids, and metallocofactors (e.g., Fe-S clusters [3] and heme [4]). Mitochondria also play an essential role as network hubs for cell signaling and regulation [5]. However, metabolic communication and biochemical trafficking between the cytoplasm and the mitochondrial matrix is severely restricted. While the mitochondrial outer membrane contains permanently open, nonselective pores (porins, or VDACs) that permit free passage to most biomolecules below about 5 kDa, transport across the inner mitochondrial membrane is mediated by carriers whose substrate selectivity prevents leakage of protons across the respiratory membrane and controls the biochemical exchanges between cytoplasmic and mitochondrial matrix spaces [6–8]. While they are known to be essential in eukaryotes [9], the individual functions performed by these carriers can be obscured in the complex milieu of a living cell, and characterization of the isolated protein is often required for a definite assignment [10]. In yeast, approximately 35 mitochondrial carrier proteins (MCPs) have been identified by genome analysis, and functions have been assigned to many of them based on the phenotypic effects of gene deletion or by directly assaying transport activity [11].

Mtm1p (YGR257cp) is a MCP that was originally identified as the Manganese Trafficking factor for Mitochondrial Sod2 based on impaired metal activation of yeast mitochondrial MnSOD in a genetic knockout [12, 13]. This assignment was later revised as cellular and organelle studies defined a role for Mtm1p in mitochondrial Fe-S cluster biosynthesis and iron homeostasis [14, 15], although the actual carrier substrate could not be identified. Knockdown of the vertebrate homolog (SLC25A39) in a zebrafish model disrupts heme biosynthesis and results in profound anemia [16], demonstrating its importance in metal metabolism and leading to the prediction that defects in this carrier will be linked to human disease.

Recently, recombinant Mtm1p was expressed in E. coli for biochemical characterization aimed at resolving the functional assignment [17]. The discovery that the purified Mtm1p protein binds pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP) with micromolar affinity suggested a new role for this carrier in PLP trafficking to the mitochondrion that accounts for all known phenotypic effects of mtm1 knockout/knockdown, including disruption of mitochondrial iron homeostasis (cysteine desulfurase [EC 2.8.1.7], a PLP-dependent enzyme, is required for Fe-S cluster biosynthesis [18]) and disruption of heme biosynthesis (5-aminolevulinate synthase (ALAS) [EC 2.3.1.37], a PLP-dependent enzyme, catalyzes the first committed step in heme biosynthesis [19]). The present work extends the characterization of PLP interactions with the purified recombinant protein and investigates the biochemical consequences of mtm1 knockout in more detail.

EXPERIMENTAL

Biological Materials

Biochemical reagents and detergents were obtained from commercial sources and used without further purification. The expression host E. coli BL21 Star (DE3) | pRIL | pET23Mtm1pTS(L78QC), containing the CodonPlus RIL plasmid (Stratagene, Carlsbad, CA) supplementing the rare tRNAs argU (AGA, AGG), ileY (AUA), and leuW (CUA), and an expression plasmid encoding the TwinStrep-tagged Mtm1pTS fusion protein with a silent substitution for codon 78 to eliminate a spurious translational initiation site, was prepared as previously described [17]. Designer deletion strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae [20] (S. cerevisiae BY4741 MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 ygr257c::KanMX4 (MTM1−, Δmtm1), and S. cerevisiae BY4700 MATa ura3Δ0 (MTM1+)) are from the American Type Culture Collection (Bethesda, MD).

Bacterial cultures were routinely maintained on Studier [21] catabolite repression medium (ZYPG) (0.5% yeast extract, 1% N-Z amine, 1× NPS, 0.2% glucose) with appropriate antibiotics (carbenicillin (C), 125 µg/mL; chloramphenicol (Cm), 35 µg/mL). Studier autoinduction [21] was used for protein expression in ZYP-5052 medium (ZYP with 0.5% glycerol, 0.05% glucose, 0.2% α-lactose) supplemented with 125 µg/mL carbenicillin and 25 µg/mL chloramphenicol. Yeast cultures were routinely maintained on YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose) [22].

Mtm1p expression and purification

A fresh ZYPG+C+Cm plate of E. coli BL21 Star (DE3) | RIL | pET23Mtm1pTS(L78QC) was used to inoculate four 2 L baffled flasks each containing 500 mL of ZYP-5052 induction medium supplemented with carbenicillin and chloramphenicol. Cultures were incubated with shaking at 30°C for 26–30 h as previously described [17]. Inclusion bodies were prepared by sonication, digestion of cell debris by lysozyme and DNase I, and repeated washing (10% B-Per (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL), followed by 2% deoxycholate (DOC), and detergent-free buffer) in purification buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8 containing 1 mM each of PMSF, DTT and EDTA), as previously described.

The insoluble inclusion body pellet containing Mtm1p was subjected to detergent solubilization and refolding, as previously described [17], with minor modifications. Briefly, 150 mg of wet inclusion body pellet was triturated into 100 µL of wash buffer (50 mM Tris HCl (pH 8), 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT) and sonicated to produce a homogeneous suspension. 1 mL of 2.5% Sarkosyl (sodium N-lauroyl sarcosinate) in 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 0.1 mM EDTA and 1 mM DTT was added, and the solution clarified by sonication in an ultrasonic bath for 2 min at room temperature. The solution was centrifuged (16,000×g, 1 h) and the clear supernatant dialyzed against 200 mL of Sarkosyl-containing column equilibration buffer (100 mM Tris HCl, pH 8, containing 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.1% Sarkosyl, and 0.5 mM PMSF). Refolded Mtm1p-TwinStrep tag fusion protein was further affinity-purified by loading onto 10 mL of Strep-Tactin Superflow High Capacity resin (IBA, Olivette, MO) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, eluting with 10 mM desthiobiotin in equilibration buffer, yielding >10 mg of purified, refolded Mtm1p.

Subcellular fractionation of yeast mitochondria

Mitochondria were purified from yeast by a modification of standard methods [23–25]. Starter cultures of Saccharomyces cerevisiae designer deletion strains were grown in 60 mL YPD medium from a single colony, inoculated into 2×500 mL YPD medium in 2 L baffled flasks to an initial optical density OD600 nm = 0.05 and grown overnight at 30°C. Freshly collected cells (10 to 12 g) were washed and treated with Zymolyase (Seikagaku, East Falmouth, MA). Spheroplasts were suspended in homogenization buffer [23] containing 2 mM 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride (AEBSF) but no bovine serum albumin and homogenized on ice with 40 strokes of the tight fitting pestle in a 40 ml Dounce Tissue Grinder (Wheaton Glass, Millville, NJ). Unbroken spheroplasts and subcellular debris were pooled and rehomogenized a total of 4 times. The partially purified mitochondria were further purified with sucrose density gradient using Beckman L8-M ultracentrifuge (113,000×g, 25,000 rpm, 4°C, 1 h). The mitochondrial suspension at the interface between 60 and 32 % sucrose layers was diluted by adding 2–3 volumes of SEM buffer [23] slowly with gentle swirling, and clumps of debris were removed. Purified mitochondria were collected by centrifugation at 16,000×g in an Eppendorf microcentrifuge for 30 min at 4 °C. The mitochondrial pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of SEM and stored in −80 °C.

PLP-ome analysis

The PLP-ome of isolated yeast mitochondria was analyzed by reductive conjugation of native PLP adducts (using sodium cyanoborohydride)[26], resolution of proteins by SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blotting using polyclonal anti-conjugated pyridoxal antibodies for visualization. Samples were normalized based on optical absorption density at 280 nm (OD280nm) measured for aliquots dissolved in 0.6% SDS solution. Yeast mitochondria prepared as described above and normalized to total protein concentration were vortexed in quantitative proteomics (QP) buffer [27] or B-Per protein extraction reagent (Thermo Fisher, Rockford, IL), and sodium cyanoborohydride (2 M solution in 0.1 M NaOH) was immediately added to a final concentration of 100 mM. A Western blotting specificity control was prepared in the same way, but with 2 M Tris HCl (pH 7.1) replacing the sodium cyanoborohydride solution. The QP solution was neutralized with 1 M acetic acid and aliquots in SDS sample loading buffer were applied to a 12% Tris-HCl Ready Gel (Bio Rad Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA). After electrophoresis, the protein was transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Trans-Blot SD Semi Dry Transfer Cell, Bio Rad Laboratories) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The membrane was blocked, washed and probed with primary antibodies (either polyclonal rabbit anti-conjugated pyridoxal (reduced) antibodies (Abcam, Eugene, OR or Advanced Targeting Systems, San Diego, CA) or monoclonal mouse anti-yeast mitochondrial porin antibodies (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), as a loading control)). Secondary antibodies (peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG-POD, or antimouse IgG-POD) were bound to permit chemiluminescent detection (Lumi-LightPLUS, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). MagicMark™ XP MW Standards (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were used for mass calibration.

5-Aminolevulinate synthase (ALAS) activity assay

ALAS activity was measured using the discontinuous assay of Mauzerall and Granick [28] as modified by Shoolingin-Jordan et al [29]. Briefly, 50 µL samples to be assayed were added to 120 µL of a 50 mM glycine solution in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) containing 2 mM succinyl CoA, with or without supplementation with 10 µM PLP. After 30 min incubation at 37°C, protein was precipitated with 150 µL of 10% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and removed by centrifugation. 300 µL of sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.6) and 25 µL of acetylacetone were added to the supernatant and the mixture was vigorously vortexed, then heated in a boiling water bath for 10 min. After cooling to room temperature for 15 min, the solution was combined with an equal volume of modified Ehrlich’s reagent (1 part by volume of 70% perchloric acid and 5.25 parts by volume of glacial acetic acid, containing 18 mg/mL 4-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde final concentration). After approximately 90 s, absorbance was measured at 553 nm.

Spectroscopic measurements

Optical absorption spectra were routinely measured using a Varian Cary 5 UV-vis-NIR absorption spectrometer (Varian Instruments, Walnut Creek, CA). Fluorescence spectra were measured using a Cary Eclipse spectrofluorometer equipped with a magnetic stirring accessory and automatic temperature control.

Extending the earlier fluorescence binding measurements [17] to a stoichiometric binding experiment involves the use of relatively high protein concentration, requiring consideration of the fraction of ligand bound in analyzing the progress curve for the titration. The free ligand concentration at each point (Li) may be estimated [30]:

| (1) |

where L0,i is the total ligand concentration in the ith step of the titration, E0 is the total protein concentration, and KD the dissociation constant for the protein-ligand complex.

| (2) |

where F0 is the initial fluorescence intensity of the sample, and Q is the total fractional quenching amplitude at saturation, (F0 – F∞)/F0.

The fluorescence intensity at each point in the titration was corrected for dilution and inner filter effects, using extinction coefficients for the ligand (PLP) measured in the sample buffer (10 mM MOPS pH 7, 0.1% Brij-35, 0.5 mM TCEP) at the excitation and emission wavelengths used in the titration (εex,290 nm = 735 M−1cm−1; εem,340 nm = 2585 M−1cm−1).

| (3) |

where Fobs,i is the fluorescence intensity measured at the ith step of the titration, V0 is the initial volume of the sample, Vi is the actual volume including titrant, b is the optical pathlength, L0,i the total ligand concentration and εex and εem the absorption coefficients for the ligand at the excitation and emission wavelengths used in the experiment. Fluorescence intensity data was analyzed by nonlinear regression (Kaleidograph, Synergy Software, Reading, PA) using equation 2.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

ITC measurements were performed using a iTC200 microcalorimeter (MicroCal, Northampton, MA). Mtm1p was prepared as a 50 µM solution in 10 mM MOPS pH 6.85, 0.5 mM TCEP, 0.1% Brij-35. PLP was prepared as a 2 mM solution in the same buffer, and neutralized to match the pH of the protein solution within 0.02 pH units. The buffer was prepared from 0.2 M pH 7.0 stock, with a final measured pH of 6.85. The 1–2 mL protein stock was dialyzed against the same buffer (350 mL each for 3 changes of buffer, 24 h equilibration time each step). Several pilot experiments were performed to determine the appropriate concentration range for the PLP titrant. The PLP stock solution was adjusted to pH 6.85, with restandardization of the probe between measurements, to exactly match the pH of the protein solution in order to avoid reaction heat from acid-base neutralization during injection of the titrant, and the buffer dilution features in the ITC data were correspondingly very small. After titration, the pH of the final titrated solution was checked once again with a pH probe. Protein and titrant solutions were degassed under vacuum, equilibrated to room temperature, and loaded into the iTC200. The binding reaction was carried out at 25°C. After an initial injection of 0.2 µL, 17 injections of 2 µL titrant were made with 10 min delay between injections. In a separate experiment, titrant was injected into a cell loaded with degassed buffer as a blank. The results were analyzed using Origin software (OriginLab, Northampton, MA) with the isothermal titration calorimetry data analysis module provided by the manufacturer. Raw titration data was corrected by subtracting the titration blank data representing the dilution heats. After baseline fitting, the corrected data was integrated and the results analyzed using standard single-site and two-site binding models.

Protein characterization

Protein concentration of purified Mtm1p protein was determined in the presence of 0.1% Brij-35 detergent using bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). The OD280nm was also routinely recorded for the purified proteins. The combined BCA assay results and OD280nm absorption measurements were used to evaluate the purity of the protein by comparing the observed mass extinction coefficient with the predicted value obtained from the ExPASy ProtParam tool [31] . Total cellular protein was prepared by the quantitative proteomics method, as previously described [27, 32]. Proteins resolved by SDS-PAGE (Ready-Gel or TGX precast gel, Bio Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) were stained with Pierce GelCode Blue Safe protein staining solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

RESULTS

Stoichiometric titration

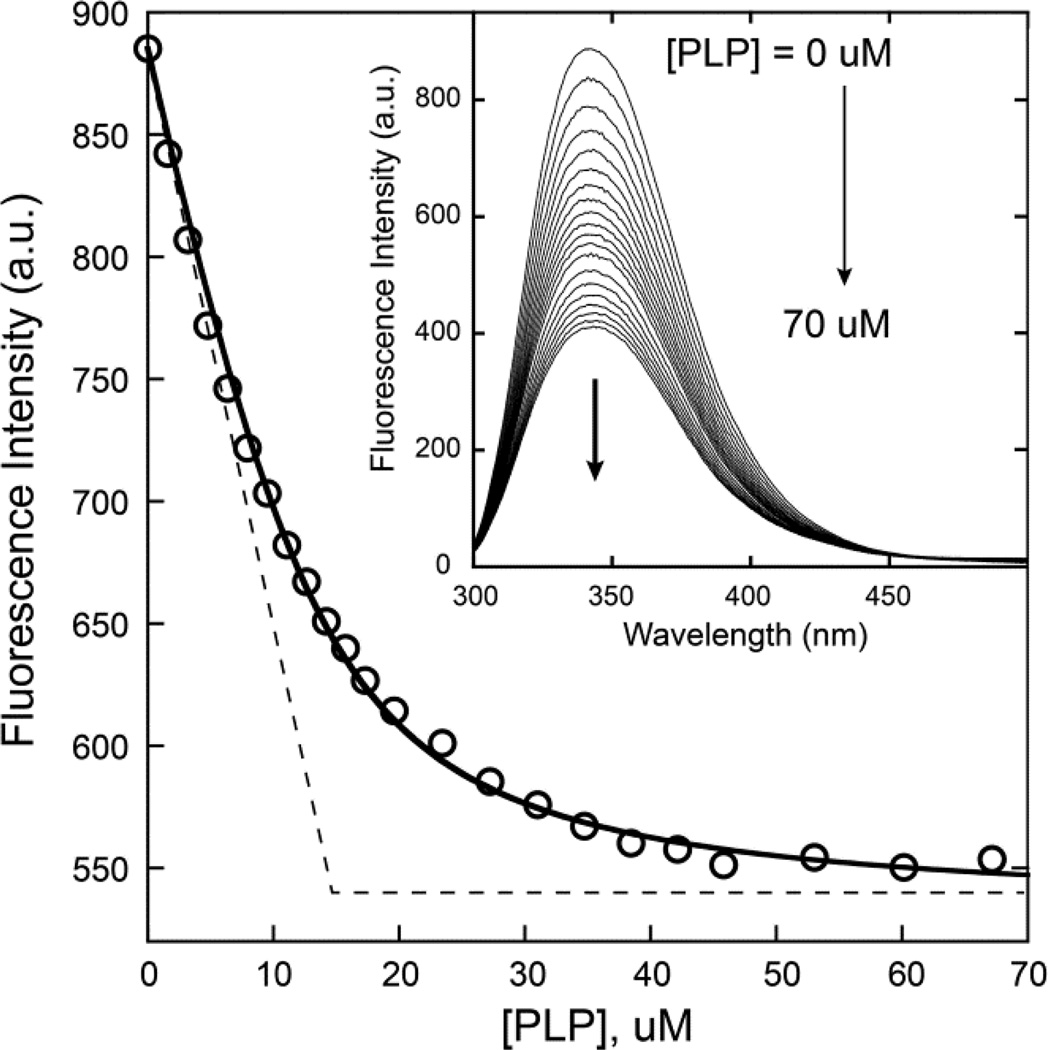

The photophysical properties of pyridoxal 5′-phosphate allow it to be used as a fluorescence probe of protein interactions. In particular, PLP quenches intrinsic protein (tryptophan) luminescence emission at 340 nm, providing a signal that can be used to monitor the progress of a titration [33–35]. In preliminary studies, this approach was used to demonstrate high affinity (KD=0.6 µM) binding of the cofactor to the purified, solubilized and refolded Mtm1p [17]. To further characterize cofactor interactions, we have extended this approach by performing a stoichiometric titration (under conditions where [P] >> KD) to determine the number of cofactor molecules in the protein complex (Fig. 1). The raw fluorescence data was corrected for dilution and inner filter effects as described in the Methods, and the corrected fluorescence intensities were fit by nonlinear regression to a binding model (Eq. 2) that takes into account the fraction of cofactor bound at each step in the titration. This analysis yields an estimate of KD=1.9±0.3 µM for dissociation of the complex, and the equivalence point implies a binding ratio of 0.98, indicating tight, specific binding of the cofactor. The KD estimated in the present experiment is slightly higher than that found previously, possibly indicating some sensitivity to protein concentration.

Figure 1.

Stoichiometric fluorescence titration of recombinant refolded Mtm1p with pyridoxal 5′-phosphate. Purified recombinant, refolded Mtm1p (15 µM) in 3 mL of 10 mM MOPS pH 6.85 containing 0.1% Brij-35 and 0.5 mM TCEP was titrated with pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP) at 25 °C, and the fluorescence emission spectrum was recorded following excitation at 290 nm (Inset). The raw fluorescence data obtained for addition of 0 – 70 mM PLP was corrected fordilution and inner filter effects as described in the Methods, and the corrected fluorescence intensity was fit to Equation 2 by nonlinear regression, yielding estimates of the quenching amplitude fraction Q = 0.39 ± 0.005 and binding affinity KD = 1.9 ± 0.3 µM (solid fitted line). The initial slope was extrapolated to the saturation limit to determine the equivalence point (dotted lines), indicating a binding stoichiometry of 0.98 PLP/Mtm1p.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

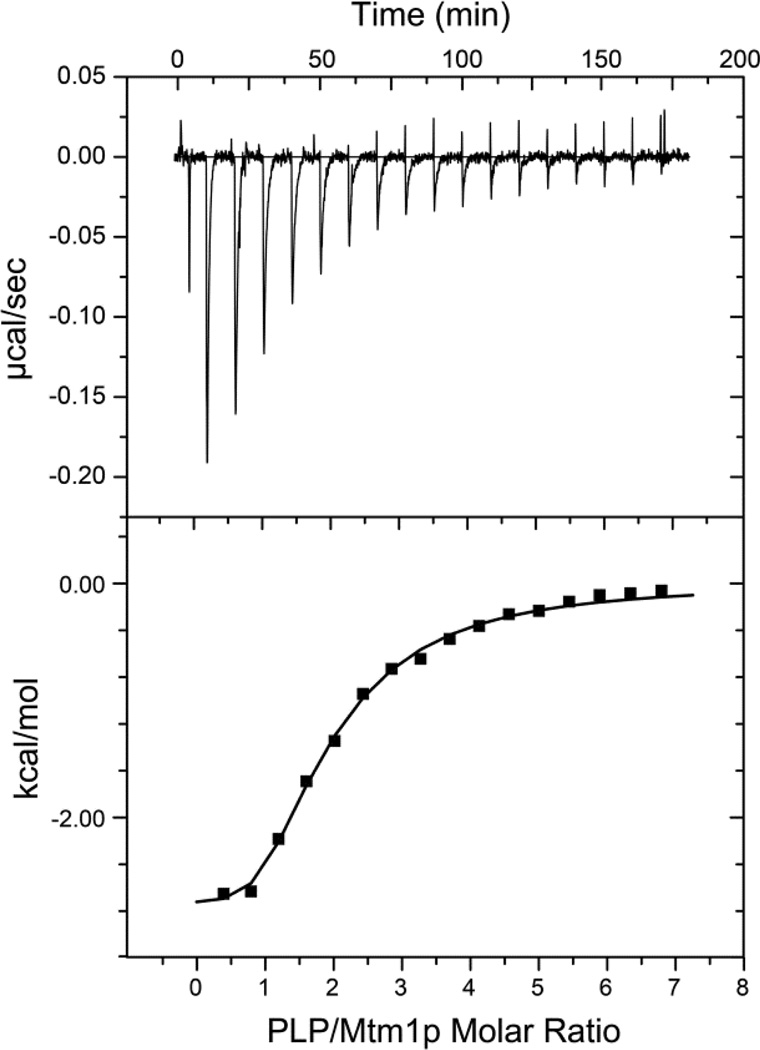

Microcalorimetry was used to investigate PLP interactions with Mtm1p in more detail, based on the enthalpic heat signature of the ligand binding reaction. Unlike the spectrofluorometric titration, which depends on quenching of intrinsic protein luminescence to detect binding, ITC is sensitive to all interactions of PLP with Mtm1p. In previous studies, ITC has proven useful in the investigation of substrate interactions of membrane carriers through analysis of the binding step involved in their transport processes [36]. We find that incremental addition of PLP to purified, refolded Mtm1p results in saturation behavior (Fig. 2, Top) implying reversible, equilibrium association of PLP with the protein. The extended recovery timecourses following each injection are consistent with the slow binding behavior observed in earlier fluorescence experiments [17], and necessitate a relatively long delay (10 minutes) between injections of titrant. Analysis of the ITC data using a single-site binding model yields estimates of the thermochemical parameters (KD= 21±3 µM; ΔH = −3.5±0.2 kcal/mol; ΔS = 10 cal/mol/deg) supporting moderately strong binding affinity, but requires a binding stoichiometry of 1.9 PLP/Mtm1p for the complex. Superstoichiometric binding is not consistent with the results from the fluorescence titration, and suggests the presence of two independent binding sites in the protein. Analysis of the ITC data in terms of two-site equilibrium complexation (Fig. 2, Bottom) requires fixing some of the 8 parameters in the model to prevent over-parameterization. By fixing the stoichiometries for the two independent binding steps to be half of the total predicted by the single-site model (N1=N2=0.95) and setting KD,1=1.9 µM (from the fluorescence titration), multiple regression analysis yields estimates of the other thermochemical parameters: ΔH1 = −2.76±0.05 kcal/mol; ΔS1 = 17 cal/mol/deg; KD,2= 47±4 µM; ΔH2 = −4.5±0.2 kcal/mol; ΔS2 = 5 cal/mol/deg). If the value of KD,1 is not fixed, a best-fit value of 0.6 µM is returned, but with unacceptably large standard errors, reflecting the strong interdependence of the parameter values. The heat of formation determined calorimetrically is small, similar to values previously reported for formation of PLP aldimine (Schiff base) complexes with amino acids and protein (ΔH = −0.8 to −1.3 kcal/mol)[37].

Figure 2.

Isothermal titration calorimetry analysis of PLP binding to Mtm1p. (Top) Mtm1p (200 µL volume, 50 µM protein in 10 mM MOPS pH 6.85, 0.5 mM TCEP, 0.1% Brij-35) was titrated with 17 injections (2 µL each, after an initial injection of 0.2 µL) of 2 mM PLP in the same buffer, as described in the Methods. The binding isotherm was corrected by subtraction of a reaction blank (dilution heat of PLP in sample buffer) and the integrated heats evaluated to determine thermochemical parameters, (Bottom). A two-site binding model fit is shown (KD,1= 1.9 µM; ΔH1= −2.76±0.05 kcal/mol; ΔS1 = 17 cal/mol/deg; KD,2= 47±4 µM; ΔH2 = −4.5±0.2 kcal/mol; ΔS2 = 5 cal/mol/deg; binding stoichiometry, N1=N2=0.95 PLP/protein). The fit was obtained by fixing KD,1and stoichiometry parameters, as described in the text.

PLP-ome analysis

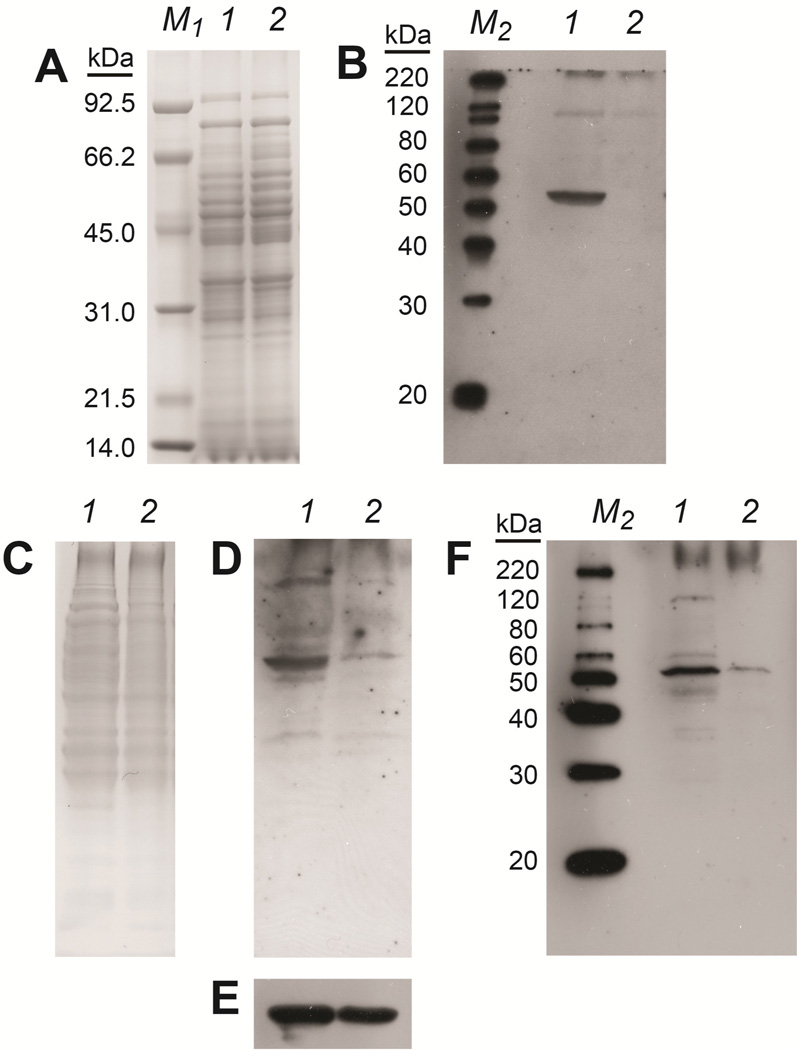

Although these in vitro studies demonstrate that Mtm1p binds the PLP cofactor in a specific, high affinity complex, more direct evidence for the biological function of this carrier can be obtained by examining the effect of Δmtm1 knockout on the PLP status of the mitochondrial proteome (the PLP-ome)[38, 39]. PLP is typically bound to enzymes in covalent complexes involving addition of lysine ε-amino group to the electrophilic aldehyde carbonyl of the cofactor forming an aldimine (Schiff base). Reduction of the aldmine by borohydride converts it to a stable, covalent lysine-pyridoxamine 5′-phosphate (PMP) conjugate that can be detected immunologically using polyclonal antibodies raised against conjugated pyridoxal. We have developed this approach to evaluate the PLP-ome of yeast mitochondria isolated from WT (MTM1+) and MTM1− knockout (Δmtm1) strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

PLP-ome analysis of purified Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondria. (Panels A–B) Mitochondria isolated from MTM1+ yeast were analyzed with (lane 1) or without (lane 2) borohydride reduction at equal protein loading. A, Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel of total mitochondrial protein. B, Western immunoblot analysis of samples as in A, probed with anti-conjugated pyridoxal Ab. (Panels C–F) Mitochondria isolated from MTM1+ (lane 1) or MTM1− (Δmtm1) (lane 2) yeast were analyzed at equal protein loading. C, Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel of total mitochondrial protein. D, Western immunoblot analysis of pyridoxal conjugates prepared by borohydride reduction as described in the Methods, detected by probing total mitochondrial protein with rabbit anti-conjugated pyridoxal Ab at equal protein loading. E, Samples as in C&D, detected using mouse anti-porin mAb as a loading control. F, Western immunoblot analysis of soluble pyridoxal conjugates prepared as described in the Methods, detected in soluble mitochondrial B-Per extracts. M1, Low Range MW Standards; M2, MagicMark™ XP MW Standards.

Knockout of mtm1 in yeast is known to result in a respiratory defect associated with the mitochondrial petite phenotype. Although the knockout yeast is able to grow on fermentative substrates (e.g., glucose), the yield of mitochondria from the yeast is significantly lower than from WT strains. In order to make a valid comparison between mitochondria isolated from the mtm1-proficient and -deficient yeast, both strains were grown under identical conditions, the cells lysed for organelle fractionation, and the mitochondria purified by sucrose density gradient ultracentrifugation. BSA was omitted from the organelle fractionation buffers in order to prevent background from PLP conjugated to BSA in Western blotting. Serum albumin is the principal protein transporting PLP in the blood [40, 41], and commercially prepared samples generally contain bound PLP cofactor. Also, commercially available anti-conjugated pyridoxal antibodies are raised against pyridoxal-conjugated BSA [42, 43], so they may be expected to be particularly sensitive to that species. The total protein content of the purified mitochondria was determined by measuring the 280 nm absorbance for samples solubilized in 0.6% SDS. Normalization of the samples to the UV absorbance results in equal Coomassie-staining material on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3, A&C).

PLP conjugation was performed by prompt borohydride reduction of samples normalized to total protein in Quantitative Proteomics buffer as described in the Methods, and protein components were resolved by gel electrophoresis. The PLP cofactor content of the mitochondrial proteome was then detected by Western immunoblot analysis using anti-conjugated pyridoxal antibodies (Fig. 3). The sensitivity of this method to the conjugated cofactor is demonstrated by comparing results for WT mitochondria with (Fig. 3, B, 1) or without (Fig. 3, B, 2) reductive conjugation. Using this approach, a dramatic difference in proteome-conjugated pyridoxal is revealed for mitochondria isolated from WT and knockout yeast (Fig. 3, Bottom). The dramatically lower global pyridoxal content of mitochondria isolated from knockout yeast (Fig. 3, D, 2) supports a role for the Mtm1p carrier in PLP trafficking to the mitochondrial matrix. At present, no mitochondrial matrix protein has been established as a loading control that is independent of metabolic state. To ensure that the results reflect an actual difference in PLP content and not simply a variation in mitochondrial loading, the blots were probed with antiyeast porin antibodies, a standard mitochondrial loading control (Fig. 3, Bottom, E). Since porins are localized to the outer mitochondrial membrane, they are relatively insensitive to metabolic state, or defects affecting the mitochondrial matrix space.

Further fractionation of the mitochondria to extract soluble proteins (Fig. 3, F) improves the quality of the Western blot, yielding estimates of the masses of the conjugated polypeptides. However, the 1-dimensional resolution the mitochondrial proteome is not sufficient to allow unambiguous identification of these proteins and assignment to PLP-dependent enzymes known to be localized to the mitochondrial matrix. We plan to extend this analysis in future work to permit specific and quantitative evaluation of the mitochondrial PLP-ome.

Interestingly, MTM1+ (Δmtm1 knockout) mitochondria appear to retain a small amount of pyridoxal cofactor (Fig. 3F, lane 2). The cofactor detected in these immunoblots may be associated with proteins outside the matrix space (i.e., the outer surface of the inner mitochondrial membrane, the intermembrane space, or the outer mitochondrial membrane). However, the cofactor appears to be associated with the same proteins in both MTM1+ and MTM1− samples. This could reflect dual localization of those proteins (e.g., to the mitochondrial matrix and intermembrane space), but it seems more likely that mechanisms exist for alternative low affinity, low efficiency PLP transport in the mitochondria, including nonspecific binding and transport by nucleotide carriers (e.g., the ADP/ATP exchanger, AAC [44]) which may account for the relatively low levels of PLP that are observed.

ALAS enzyme activity

Knockdown of the vertebrate homolog of Mtm1p in zebrafish (SLC25A39p) has been shown to result in profound anemia [16], indicating an essential role for this MCP in heme biosynthesis, but previous studies were unable to account for this connection in specific metabolic terms. In yeast, mtm1 knockout results in a respiratory defect and development of the mitochondrial petite phenotype, but a specific link to heme metabolism in yeast has not been previously investigated, although the heme content of Δmtm1 yeast mitochondria has been reported to be relatively low [15]. Our hypothesis that Mtm1p plays an essential role in mitochondrial PLP trafficking leads to the prediction that disruption of Mtm1p function in the mitochondrion will result in inactivation of 5-aminolevulinate synthase, a PLP-dependent enzyme catalyzing the first committed step of heme biosynthesis.

In order to test this prediction, we assayed ALAS activity in samples of mitochondria purified from WT and knockout yeast, normalized to total protein (Table 1). Again, the results indicate a dramatic difference in ALAS activity in the two samples, consistent with a deficiency in PLP in mitochondria lacking Mtm1p. ALAS activity in MTM1− mitochondrial extracts without addition of PLP was less than 10% that measured in MTM1+ extracts. PLP supplementation increased activity in both MTM1+ and MTM1− samples, with a 2.5-fold increase for the former and 7-fold-increase for the latter. The lower maximal ALAS activity observed for the Mtm1p-deficient mitochondria may indicate that the ALAS apoenzyme is unstable in the absence of PLP. Cofactor binding is known to significantly increase the stability of PLP-dependent enzymes, with as much as 30 kcal/mol stabilization of the PLP complex reported for cytosolic aspartate aminotransferase [45], and PLP binding has been reported to induce large conformational changes in the β-subunit of tryptophan synthase [46]. There is also evidence, at least in mammalian cells, for a mitochondrial protease that selectively degrades the ALAS apoprotein [47]. These results suggest that cofactor limitation in MTM1− mitochondria may affect the levels of matrix enzyme by altering the rate of protein recycling.

Table 1.

5-Aminolevulinate synthase activity analysis

| Strain | ALAS Specific Activity (nmol•µg−1•h−1) a | |

|---|---|---|

| −PLP | +PLP | |

| MTM1+ | 9.4±0.7 | 23.3±0.6 |

| MTM1− (Δmtm1) | 0.8±0.4 | 5.4±0.9 |

ALAS enzymatic activity measured for Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondria isolated from MTM1+ and MTM1− (Δmtm1) yeast as described in the Methods, with or without addition of PLP to the assay. Samples were normalized to total protein based on optical density at 280 nm after solubilization in SDS. The average value and standard deviation for the results of three independent determinations are shown.

DISCUSSION

The pleiotropic effects of genetic deletion of the Mtm1p mitochondrial carrier, reflected in phenotypic defects in iron homeostasis (accumulation of ferric hydroxide nanoparticles in the mitochondrial matrix), heme biosynthesis, and respiration [14–16], dramatically illustrate how loss of a single biochemical species can disrupt many aspects of cellular metabolism. However, the complexity of these defects also underscores the difficulty of assigning biological functions to individual components in the context of the complete, intact cell. We have used molecular approaches to characterize the purified recombinant Mtm1p mitochondrial carrier, demonstrating high affinity, specific binding of the pyridoxal 5′-phosphate cofactor, which would be expected for a PLP carrier. The effect of Δmtm1 knockout on isolated yeast mitochondria provides additional evidence for a role in PLP cofactor transport in vivo, as depletion of the PLPome in mitochondria from Δmtm1 knockout yeast may reflect a defect in PLP delivery to the matrix space. Cofactor limitation can also be demonstrated at the individual enzyme level by assaying activity in the absence of added cofactor. The activity of 5-aminolevulinate synthase was found to be nearly undetectable in mitochondria from knockout yeast, but could be partially restored in extracts by PLP supplementation. This PLP limitation for a key pathway enzyme indicates that Δmtm1 knockout affects heme biosynthesis in yeast as well as vertebrates, accounting for the pronounced respiratory defects of Δmtm1 yeast.

The hypothesis that Mtm1p plays an essential role in mitochondrial PLP trafficking resolves outstanding questions relating to the mitochondrial metallome, highlighting the powerful link between PLP transport and mitochondrial iron homeostasis that results from key roles played by a number of PLP-dependent enzymes in iron metabolism [18, 19, 48, 49]. This linkage provides an exceptional example of the integration of metabolic processes, where trafficking of a cofactor between distinct metabolic subsystems of the cell (the cytoplasm and the mitochondrial matrix) broadly affects metal homeostasis and respiration by determining the activity of specific, essential pathway enzymes. Further detailed studies will be needed to evaluate the substrate requirements of the Mtm1p carrier in the context of in vitro liposome-based transport assays to definitively establish its carrier function. Extension of this assignment to homologs in other organisms, including humans (SLC25A39p), may be expected to provide new insight into the importance of mitochondrial PLP trafficking in the health of the eukaryotic cell.

Research Highlights.

Recombinant yeast carrier Mtm1p stoichiometrically binds PLP

The mitochondrial proteome of Δmtm1 knockout yeast is depleted of PLP

5-Aminolevulinate synthase is PLP-deficient in Δmtm1 yeast

Mtm1p carrier links PLP cofactor trafficking to mitochondrial iron metabolism

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Eric Gouaux (Vollum Institute, OHSU) for providing access to the iTC200 microcalorimeter in his laboratory.

FUNDING

Abbreviations

- MCP

mitochondrial carrier protein

- PLP

pyridoxal 5′-phosphate

- PMP

pyridoxamine 5′-phosphate

- ALAS

5-aminolevulinate synthase

- MnSOD

manganese superoxide dismutase

- PMSF

phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride

- DOC

deoxycholate

- TCEP

tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine

- TCA

trichloracetic acid

- AEBSF

4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride

- QP

quantitative proteomics

- C

carbenicillin

- Cm

chloramphenicol

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

This work was supported by NIH grant R01 GM42680 and the OHSU Presidential Bridge Fund to J.W.W.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schatz G. The Magic Garden. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 2007;76:673–678. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.060806.091141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McBride HM, Neuspiel M, Wasiak S. Mitochondria: more than just a powerhouse. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:R551–R560. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barras F, Loiseau L, Py B. How Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae build Fe/S proteins. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 2005;50:41–101. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2911(05)50002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ajioka RS, Phillips JD, Kushner JP. Biosynthesis of heme in mammals. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1763:723–736. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sies H. Role of metabolic H2O2generation: redox signaling and oxidative stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:8735–8741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R113.544635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wohlrab H. Transport proteins (carriers) of mitochondria. IUBMB Life. 2009;61:40–46. doi: 10.1002/iub.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palmieri F, Pierri CL. Mitochondrial metabolite transport. Essays Biochem. 2010;47:37–52. doi: 10.1042/bse0470037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palmieri F. The mitochondrial transporter family SLC25: identification, properties and physiopathology. Mol. Aspects Med. 2013;34:465–484. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palmieri F. Diseases caused by defects of mitochondrial carriers: a review. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1777:564–578. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palmieri F, Indiveri C, Bisaccia F, Iacobazzi V. Mitochondrial metabolite carrier proteins: purification, reconstitution, and transport studies. Methods Enzymol. 1995;260:349–369. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)60150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palmieri L, Runswick MJ, Fiermonte G, Walker JE, Palmieri F. Yeast mitochondrial carriers: bacterial expression, biochemical identification and metabolic significance. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2000;32:67–77. doi: 10.1023/a:1005564429242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luk E, Carroll M, Baker M, Culotta VC. Manganese activation of superoxide dismutase 2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae requires MTM1, a member of the mitochondrial carrier family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:10353–100357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1632471100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luk E, Yang M, Jensen LT, Bourbonnais Y, Culotta VC. Manganese activation of superoxide dismutase 2 in the mitochondria of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:22715–22720. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504257200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang M, Cobine PA, Molik S, Naranuntarat A, Lill R, Winge DR, Culotta VC. The effects of mitochondrial iron homeostasis on cofactor specificity of superoxide dismutase 2. EMBO J. 2006;25:1775–1783. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park J, McCormick SP, Chakrabarti M, Lindahl PA. Insights into the ironome and manganese-ome of Δmtm1 Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondria. Metallomics. 2013;5:656–672. doi: 10.1039/c3mt00041a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nilsson R, Schultz IJ, Pierce EL, Soltis KA, Naranuntarat A, Ward DM, Baughman JM, Paradkar PN, Kingsley PD, Culotta VC, Kaplan J, Palis J, Paw BH, Mootha VK. Discovery of genes essential for heme biosynthesis through large-scale gene expression analysis. Cell Metab. 2009;10:119–130. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whittaker MM, Whittaker JW. Expression and Purification of Recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mitochondrial Carrier Protein YGR257Cp (Mtm1p) . Prot. Exp. Purif. 2014;93:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mühlenhoff U, Balk J, Richhardt N, Kaiser JT, Sipos K, Kispal G, Lill R. Functional characterization of the eukaryotic cysteine desulfurase Nfs1p from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:36906–36915. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406516200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Volland C, Felix F. Isolation and properties of 5-aminolevulinate synthase from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eur. J. Biochem. 1984;142:551–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winzeler EA, Shoemaker DD, Astromoff A, Liang H, Anderson K, Andre B, Bangham R, Benito R, Boeke JD, Bussey H, Chu AM, Connelly C, Davis K, Dietrich F, Dow SW, El Bakkoury M, Foury F, Friend SH, Gentalen E, Giaever G, Hegemann JH, Jones T, Laub M, Liao H, Liebundguth N, Lockhart DJ, Lucau-Danila A, Lussier M, M'Rabet N, Menard P, Mittmann M, Pai C, Rebischung C, Revuelta JL, Riles L, Roberts CJ, Ross-MacDonald P, Scherens B, Snyder M, Sookhai-Mahadeo S, Storms RK, Véronneau S, Voet M, Volckaert G, Ward TR, Wysocki R, Yen GS, Yu K, Zimmermann K, Philippsen P, Johnston M, Davis RW. Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science. 1999;285:901–906. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5429.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Studier FW. Protein production by auto-induction in high density shaking cultures. Prot. Expr. Purif. 2005;41:207–234. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Treco DA, Winston F. Growth and manipulation of yeast Chapter 13:Unit 13.2. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2008 doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb1302s82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gregg C, Kyryakov P, Titorenko VI. Purification of mitochondria from yeast cells. J. Vis. Exp. 2009;(30):e1417. doi: 10.3791/1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boldogh IR, Pon LA. Purification and subfractionation of mitochondria from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Cell. Biol. 2007;80:45–64. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(06)80002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang J, Ruiz V, Vancura A. Purification of yeast membranes and organelles by sucrose density gradient centrifugation. Methods Mol. Biol. 2008;457:141–149. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-261-8_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wadsworth RI, White MF. Identification and properties of the crenarchaeal single-stranded DNA binding protein from Sulfolobus solfataricus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:914–920. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.4.914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von der Haar T. Optimized Protein Extraction for Quantitative Proteomics of Yeasts. PLoS ONE. 2007;10:e1078 1–e1078 8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mauzerall D, Granick S. The occurrence and determination of d-aminolevulinic acid and porphobilinogen in urine. J. Biol. Chem. 1956;219:435–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shoolingin-Jordan PM, LeLean JE, Lloyd AJ. Continuous coupled assay for 5-aminolevulinate synthase. Methods Enzymol. 1997;281:309–316. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)81037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou M, Van Etten RL. Structural basis of the tight binding of pyridoxal 5'-phosphate to a low molecular weight protein tyrosine phosphatase. Biochemistry. 1999;38:2636–2646. doi: 10.1021/bi9823737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gasteiger E, Hoogland C, Gattiker A, Duvaud S, Wilkins MR, Appel RD, Bairoch A. Protein Identification and Analysis Tools on the ExPASy Server. In: Walker JM, editor. The Proteomics Protocols Handbook. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2005. pp. 571–607. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whittaker MM, Whittaker JW. Metallation state of human manganese superoxide dismutase expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012;523:191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang BI, Metzler DE. Pyridoxal 5'-phosphate and analogs as probes of coenzyme-protein interaction. Methods Enzymol. 1979;62:528–551. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)62259-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bueno C, Pavez P, Salazar R, Encinas MV. Photophysics and photochemical studies of the vitamin B6 group and related derivatives. Photochem. Photobiol. 2010;86:39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2009.00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vázquez MA, Muñoz F, Donoso J, García Blanco F. Band-shape analysis and resolution of electronic spectra of pyridoxal phosphate with amino acids. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1991;2:275–281. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaur J, Olkhova E, Malviya VN, Grell E, Michel H. A L-lysine transporter of high stereoselectivity of the amino acid-polyamine-organocation (APC) superfamily: production, functional characterization, and structure modeling. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:1377–1387. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.510743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giartosio A, Salerno C, Franchetta F, Turano CA. Calorimetric study of the interaction of pyridoxal 5'-phosphate with aspartate apoaminotransferase and model compounds. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:8163–8170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Percudani R, Peracchi A. The B6 database: a tool for the description and classification of vitamin B6-dependent enzymatic activities and of the corresponding protein families. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:273. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Percudani R, Peracchi AA. A genomic overview of pyridoxal-phosphatedependent enzymes. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:850–854. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fonda ML, Trauss C, Guempel UM. The binding of pyridoxal 5'-phosphate to human serum albumin. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1991;288:79–86. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90167-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hilak MC, Harmsen BJ, Joordens JJ, Van Os GA. Binding of pyridoxal 5'-phosphate to bovine serum albumin and albumin fragments obtained after proteolytic hydrolysis. Localization and nature of the primary PLP binding site. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 1975;7:411–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1975.tb02461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brandon DL, Corse JW, Windle JJ, Layton LL. Two homogeneous immunoassays for pyridoxamine. J. Immunol. Methods. 1985;78:87–94. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(85)90331-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Córdoba F, Gonzalez C, Rivera P. Antibodies against pyridoxal 5'-phosphate and pyridoxamine 5'-phosphate. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1966;127:151–158. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pebay-Peyroula E, Dahout-Gonzalez C, Kahn R, Trézéguet V, Lauquin GJ, Brandolin G. Structure of mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier in complex with carboxyatractyloside. Nature. 2003;426:39–44. doi: 10.1038/nature02056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Relimpio A, Iriarte A, Chlebowski JF, Martinez-Carrion M. Differential scanning calorimetry of cytoplasmic aspartate transaminase. J. Biol. Chem. 1981;256:4478–4488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nishio K, Ogasahara K, Morimoto Y, Tsukihara T, Lee SJ, Yutani K. Large conformational changes in the Escherichia coli tryptophan synthase beta(2) subunit upon pyridoxal 5'-phosphate binding. FEBS J. 2010;277:2157–2170. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aoki Y. Crystallization and characterization of a new protease in mitochondria of bone marrow cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1978;253:2026–2032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oppenheim EW, Adelman C, Liu X, Stover PJ. Heavy chain ferritin enhances serine hydroxymethyltransferase expression and de novo thymidine biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:19855–19861. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100039200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Woeller CF, Fox JT, Perry C, Stover PJ. A ferritin-responsive internal ribosomal entry regulates folate metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:29927–29935. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706264200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]