Summary

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans is a perio-pathogenic bacteria that has long been associated with localized aggressive periodontitis. The mechanisms of its pathogenicity have been studied in humans and pre-clinical experimental models. Although different serotypes of A. actinomycetemcomitans have differential virulence factor expression, A. actinomycetemcomitans cytolethal distending toxin (CDT), leukotoxin, and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) have been most extensively studied in the context of modulating the host immune response. Following colonization and attachment in the oral cavity, A. actinomycetemcomitans employs CDT, leukotoxin, and LPS to evade host innate defense mechanisms and drive a pathophysiologic inflammatory response. This supra-physiologic immune response state perturbs normal periodontal tissue remodeling/turnover and ultimately has catabolic effects on periodontal tissue homeostasis. In this review, we have divided the host response into two systems: non-hematopoietic and hematopoietic. Non-hematopoietic barriers include epithelium and fibroblasts that initiate the innate immune host response. The hematopoietic system contains lymphoid and myeloid-derived cell lineages that are responsible for expanding the immune response and driving the pathophysiologic inflammatory state in the local periodontal microenvironment. Effector systems and signaling transduction pathways activated and utilized in response to A. actinomycetemcomitans will be discussed to further delineate immune cell mechanisms during A. actinomycetemcomitans infection. Finally, we will discuss the osteo-immunomodulatory effects induced by A. actinomycetemcomitans and dissect the catabolic disruption of balanced osteoclast-osteoblast mediated bone remodeling, which subsequently leads to net alveolar bone loss.

Keywords: Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, periodontitis, inflammation, osteoclast, osteoblast

Introduction

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans is a Gram negative capnophilic coccobacillus, which is commonly isolated from the oral cavity of adolescents and young adults afflicted by aggressive periodontal disease states (Newman et al., 1976; Slots, 1976; Slots et al., 1980). In youth, localized aggressive periodontitis, formally known as localized juvenile periodontitis (Armitage, 1999), was classically described as affecting preferentially the succedaneous 1st molars and incisors (Van der Weijden et al., 1994). In addition, A. actinomycetemcomitans has been implicated in extra-oral infections, including infective endocarditis (Nakano et al., 2007), bacterial arthritis (Cuende et al., 1996), pregnancy associated septicemia (Shalini et al., 1995), cerebral abscesses (Stepanovic et al., 2005; Zijlstra et al., 1992), and osteomyelitis (Antony et al., 2009). The primary source however is ultimately the oral cavity (Fine et al., 2007; van Winkelhoff et al., 1993; Zambon, 1985), thus requiring translocation of A. actinomycetemcomitans from the oral cavity to extra-oral infection sites.

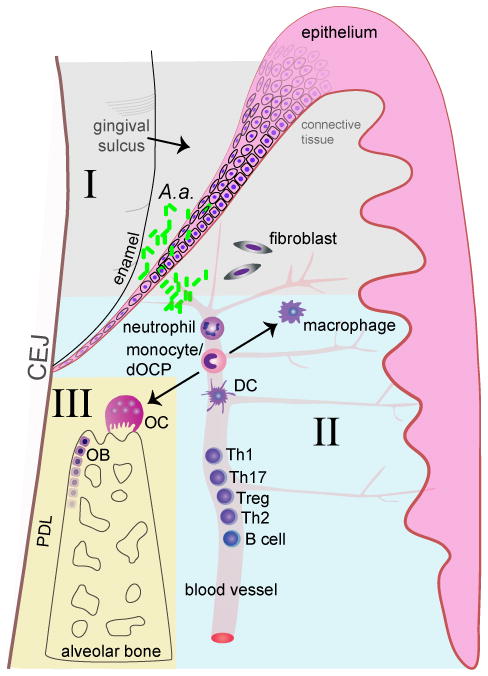

This review will critically evaluate host immune response mechanisms to A. actinomycetemcomitans in the following categories (Fig. 1):

Figure 1. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans colonizes the gingival sulcus by attachment to the sulcular/junctional epithelium cells.

It subsequently invades through the epithelium via pro-apoptotic virulence mechanisms and penetrates into the subgingival connective tissue where is stimulates epithelial cells and fibroblasts to secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines (I). Neutrophils and monocytes are thereby recruited to the local site of infection and perpetuate the host inflammatory response Subsequently, B and T cells are recruited to the diseased periodontium from the circulation (II). T cells secrete pro-resorptive factors that drive osteoclast (OC) formation and drive bone resorption. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans simultaneously impairs osteoblast (OB) function, perturbing bone remodeling processes, which ultimately results in catabolic alveolar bone loss (III).

Response of initial non-hematopoietic host barriers to A. actinomycetemcomitans: epithelium and fibroblast function

Response of cells of hematopoietic origin to A. actinomycetemcomitans: myeloid and lymphoid lineages

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans induced osteo-immunomodulatory effects impacting osteoclast-osteoblast mediated alveolar bone remodeling

In periodontal health the oral cavity is colonized by the oral commensal (non-pathogenic) flora. Under physiological states the normal oral flora stimulates the innate immune defense system in the periodontium, which controls bacterial colonization of periodontal tissues in close proximity to the gingival sulcus. In this periodontal microenvironment, A. actinomycetemcomitans infection induces a supra-physiological immune-inflammatory response state, which disrupts normal periodontal tissue homeostasis in the gingiva, periodontal ligament (PDL), cementum, and alveolar bone, ultimately promoting tooth loss. Clinical treatment of aggressive periodontal disease historically proves to be challenging. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans depletion is poorly achieved by scaling and root planing (Christersson et al., 1985; Kornman et al., 1985; Renvert et al., 1990). However, scaling and root planning with concomitant systemic antibiotic therapy or surgical intervention supports the realization of desirable microbiological and clinical outcomes (Christersson et al., 1985; Kornman et al., 1985). While there are six serotypes of A. actinomycetemcomitans, serotypes a, b, and c have been isolated most often from periodontal diseased sites (Bandhaya et al., 2012; Fine et al., 2007; Kawamoto et al., 2009). Different serotypes possess differential virulence factor expression, making some serotypes more pathogenic than others. For example concerning leukotoxin (LtxA), a surface-associated and secreted protein by A. actinomycetemcomitans (Kachlany et al., 2000), levels are variable on serotypes a-c, but higher concentrations may enhance A. actinomycetemcomitans pathogenesis with the potential to exacerbate periodontal disease progression. To date, animal experimental periodontal disease models have been the primary means used to advance the understanding of cellular mechanisms mediating A. actinomycetemcomitans pathogenesis.

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans virulence factors interact with host cells to initiate an aberrant inflammatory response in the periodontal gingival tissues. While it has been reported that trans-epithelial migration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) into the gingival sulcus results in a formed pseudo-barrier, which is several cell layers thick between the plaque and junctional/sulcular epithelium surface (Garant, 1976), this review considers the gingival epithelium to be the initial barrier to A. actinomycetemcomitans. First responders are non-hematopoietic resident cells: gingival fibroblasts and epithelium cells. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans stimulates the host responses via exotoxic and endotoxic virulence factors, activating superficial epithelial cells and underlying fibroblast cells. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans can effectively migrate through the gingival epithelium (Fives-Taylor et al., 1999), and once A. actinomycetemcomitans bypasses these initial barriers, a host inflammatory response is initiated. Once A. actinomycetemcomitans penetrates deeper in the subgingival tissues, a broader host immune response is activated.

Following the initial colonization, innate immune cells derived from the myeloid hematopoietic origin such as monocytes, neutrophils, and dendritic cells (DCs) are recruited into the periodontal microenvironment. Notably and highly central to its pathogenicity, A. actinomycetemcomitans has intrinsic defense mechanisms against host cells. Leukotoxin and cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) are A. actinomycetemcomitans exotoxins that contribute to its pathogenesis. CDT was detectable in a majority of A. actinomycetemcomitans isolated from Swedish (Ahmed et al., 2001) and Brazilian cohorts (Fabris et al., 2002). Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans strains with leukotoxin are also associated with aggressive periodontal disease states (Bueno et al., 1998; Haraszthy et al., 2000). Leukotoxin is thought to be the main A. actinomycetemcomitans constituent that causes cell death of monocytes (Taichman et al., 1980), PMNs (Taichman et al., 1980), and T cells (Mangan et al., 1991), and facilitates A. actinomycetemcomitans evasion of host defense mechanisms.

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans perpetuation of the host immune system promotes adaptive immune responses by T and B cells that are derived from lymphoid progenitors in the hematopoietic system. Initial responding resident tissue macrophages and DCs secrete cytokines and chemokines to promote activation and recruitment of B and T cells, which are found at high density in periodontal disease afflicted sites (Lin et al., 2011; Page et al., 1976). Patients with localized aggressive periodontitis had circulating opsonic IgG antibodies against A. actinomycetemcomitans (Baker et al., 1989), which are secreted by mature B cells (plasma cells). Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans also induces cytokines that polarize T helper (Th) cells, including Th1, Th2, Treg, and Th17 cells. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans stimulates interferon (IFN)-y and interleukin (IL)-12 production that polarize Th1 (Garlet et al., 2005; Kobayashi et al., 2000) cells and IL-4 that polarizes Th2 cells (Garlet et al., 2006). Thus, A. actinomycetemcomitans initiates a complex Th1 and Th2 response during disease progression.

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans immune stimulation in the periodontal microenvironment elicits a pathophysiologic pro-inflammatory state, which disrupts normal periodontal tissue remodeling processes ultimately promoting collateral tissue damage. In periodontal disease, the supra-physiologic level of pro-inflammatory and pro-resorptive cytokines favors alveolar bone resorption by monocyte or defined osteoclast progenitor (dOCP) derived osteoclasts, versus alveolar bone formation by mesenchymal derived osteoblastic cells. When bone resorption exceeds bone formation, an unbalanced bone remodeling process having catabolic effects on alveolar bone homeostasis, ultimately results in net alveolar bone loss (Baron et al., 1978). Bone-lining tartrate resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) positive multinucleated osteoclasts secrete bone degradation enzymes, including matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and cathepsin K in the acidic sealing zone microenvironment, via integrin protein adherence to the bone surface (McCauley et al., 2002; Teitelbaum et al., 1997). Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans has been shown to induce osteoclast formation and bone loss in rodent animal models (Dunmyer et al., 2012; Garlet et al., 2005; Lima et al., 2010). Pro-inflammatory cytokines with potent pro-resorptive actions, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-1, and IL-6 are highly upregulated by A. actinomycetemcomitans and thus promote osteoclast formation and bone resorption (Assuma et al., 1998; Chiang et al., 1999; Hotokezaka et al., 2007; Ishimi et al., 1990; Zhang et al., 2001). In humans, A. actinomycetemcomitans positive patients had significantly greater periodontal bone loss than the A. actinomycetemcomitans negative subjects (Fine et al., 2007), supporting A. actinomycetemcomitans’s remarkable impact on periodontal disease associated alveolar bone loss.

I. Response of initial non-hematopoietic host barriers to A. actinomycetemcomitans: epithelium and fibroblast function

Non-hematopoietic barriers to A. actinomycetemcomitans include gingival epithelial cells, resident gingival fibroblasts, and PDL fibroblasts. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans has the ability to adhere to mucosal and gingival epithelial cells, which is believed to be essential for its initial colonization in the oral cavity (Arirachakaran et al., 2012; Meyer et al., 1994). Fibroblasts derived from a mesenchymal stem cell origin are extracellular matrix collagen building cells capable of responding to pathogenic insult. Although osteoblasts are derived from non-hematopoietic precursors, they are discussed in detail in section III of this review. See Table 1 for a comprehensive list of known non-hematopoietic cellular interactions with A. actinomycetemcomitans.

Table 1. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans.

Cellular Interactions and Effectors

| Cell origin | Cell type | Virulence factor | Effector (s) | Reference (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-hematopoietic | Epithelial | LPS, whole bacteria | TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-15 | Dickinson et al., 2011; Suga et al., 2013 |

| Fibroblast | CDT, whole bacteria | RANKL, IL-6 | Belibasakis et al., 2005a; Belibasakis et al., 2005b | |

| Osteoblast | LPS | NO | Sosroseno et al., 2009 | |

| Hematopoietic | Monocyte/macrophage | LPS, CDT, Leukotoxin, whole bacteria | IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, IL-12, PGE2, CXCL1, L-1β, IL-18, NO | Belibasakis et al., 2012; Blix et al., 1998; Kelk et al., 2011; Okinaga et al., 2015; Park et al., 2014; Patil et al., 2008; Shenker et al., 2015; Yu et al., 2011a |

| Neutrophil | Whole bacteria | ROS | Guentsch et al., 2009; Permpanich et al., 2006 | |

| Dendritic cell | Whole bacteria | IL-12, IL-10, IFN-γ | Kikuchi et al., 2004 | |

| Th cell | GroEL, OMP29 | IL-10, IFN-γ, TNF-α, RANKL | Lin et al., 2011; Saygili et al., 2012 | |

| Treg | Whole bacteria | IL-10, TGF-β | Araujo-Pires et al., 2015 | |

| Osteoclast | LPS | CXCL1, CXCL2 | Valerio et al., 2014 |

Gingival epithelium invasion and apoptosis

In an in vitro model, A. actinomycetemcomitans was able to migrate through three layers of human gingival epithelium cells by upregulating pro-inflammatory cytokine production of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and increasing cell apoptosis (Dickinson et al., 2011). IL-8 in particular is a chemotactic ligand to CXCR1 and CXCR2 expressed on neutrophils, which are primary innate immune cells central to the host defense response. A study utilizing the A. actinomycetemcomitans rat-feeding model found that A. actinomycetemcomitans mediated gingival epithelium apoptosis through the caspase 3/7 pathway (Kang et al., 2012). At the subcellular level, A. actinomycetemcomitans stimulated Smad2 phosphorylation via TGF-βR1 signaling in human gingival epithelium cells and the human epithelial cell line OBA9 leading to cleaved caspase 3 activity and subsequent cell apoptosis (Yoshimoto et al., 2014). These findings indicate the potential for A. actinomycetemcomitans to traverse gingival epithelium through pro-apoptotic mechanisms. Disruption of the gingival epithelium results in the induction of a pathologic inflammatory periodontal microenvironment that supports recruitment of hematopoietic lineage derived immune response cells to subgingival tissues.

Fibroblasts initiate inflammation

Resident gingival and PDL fibroblasts are two distinct fibroblast subsets located in the periodontium that act as first responders to A. actinomycetemcomitans infection. DNA microarray analysis revealed differential gene expression of gingival fibroblasts and PDL fibroblasts (Han et al., 2002). Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans promoted secretion of IL-6 and IL-8 from human gingival fibroblasts (Belibasakis et al., 2005b; Im et al., 2015). Although A. actinomycetemcomitans did not stimulate IL-1β and TNF-α secretion from gingival fibroblasts (Belibasakis et al., 2005b), both cytokines stimulated RANKL promoter activity and cell surface expression on bone marrow stromal cells through the p38 mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway (Belibasakis et al., 2005b; Rossa et al., 2006; Rossa et al., 2005). Bone marrow stromal cells can differentiate into fibroblasts under defined culture conditions. IL-1β and TNF-α cytokines also stimulated p38 and JNK phosphorylation in immortalized mouse PDL fibroblasts (Rossa et al., 2005). Resident gingival and PDL fibroblasts elaborate pro-inflammatory mediators consistent with the early immune-inflammatory response during A. actinomycetemcomitans elicited perio-pathogenesis.

II. Response of cells of hematopoietic origin to A. actinomycetemcomitans: myeloid and lymphoid lineages

Host innate immune-inflammatory cells are responsible for phagocytizing, clearing, and secreting effector molecules necessary for defending against perio-pathogenic bacteria. The mechanisms mediating host inflammatory cell recruitment by A. actinomycetemcomitans have been studied in experimental animal models and characterized in clinical investigations of aggressive periodontal disease. Circulating host immune cells possess surface integrins and chemokine receptors that facilitate crossing the vascular endothelium in response to local chemokines present in the periodontal tissue matrix. Once inflammatory cells are recruited to the local site of infection, they employ overlapping and unique effector defense functions. Inflammatory cells identified during A. actinomycetemcomitans infection include, but are not limited to, myeloid-derived macrophages, neutrophils, and DCs, and B and T lymphocyte populations. See Table 1 for a more comprehensive list of known hematopoietic cellular interactions with A. actinomycetemcomitans.

Chemokine and chemokine receptor recruitment of inflammatory cells

Chemokines recruit inflammatory cells to the local site of infection through cell surface chemokine receptors. Garlet et al. (2003, 2005) characterized chemokine/chemokine receptor signaling in clinical and experimental rodent A. actinomycetemcomitans infected periodontal tissues. In patients afflicted by aggressive periodontal disease, tissue biopsies had increased gene expression of CCL3 (MIP-1α), CCR5, CXCR3, and interferon inducible protein (IP)-10 (CXCL10) (Garlet et al., 2003). Both CCR5 and CXCR3 are Th1 receptors that respond to CCL3 and IP-10 respectively, but these receptors are expressed by multiple cell types and are characterized by non-specific ligand binding. For example, F4/80+ macrophages concomitantly expressed CCR5 and CCR1 surface receptors, both of which are the receptors for CCL3, in response to oral A. actinomycetemcomitans inoculation in a murine periodontal disease model (Repeke et al., 2010). In a similar mouse model, CCL3, CCL4 (MIP-1β), CCL5 (RANTES), and CCL11 transcript expression was also detected early and sustained throughout the 60-day study duration (Garlet et al., 2005). Interestingly, a human longitudinal study suggested that elevated CCL3 was a prognostic marker for bone loss in periodontal disease subjects colonized by A. actinomycetemcomitans (Fine et al., 2009).

In the oral murine A. actinomycetemcomitans infection model, infiltrating cells assessed via flow cytometry showed that Gr1+ cell (neutrophil marker) numbers increased more significantly than F4/80+ cells (macrophage marker) 24 hours following initial inoculation (Garlet et al., 2005). CXCL1, a chemo-attractant cytokine whose primary role is to recruit neutrophils through ligand binding to CXCR1 and CXCR2 receptors, was the first chemokine mRNA upregulated in response to A. actinomycetemcomitans inoculation (Garlet et al., 2005). CD3+CD4+ and CD3+CD8+ T lymphocytes were significantly increased at 1 week post-infection (Garlet et al., 2005). Lastly, CD19+ B lymphocytes began to increase after 15 days and a Th-2 type response occurred after 30 days (Garlet et al., 2005). While certain chemokine receptors are more highly expressed on specific immune cell populations, it must be noted that they are not unique to specific immune cell lineages. Similarly, chemokines are secreted by many cell types and typically function as ligands having affinity for more than one receptor. The incompletely understood pleotropism and functional redundancy associated with a non-specific immune cell chemokine-chemokine receptor interactions implicate the importance of fine-tuned regulation in the host defense response during A. actinomycetemcomitans infection (Garlet et al., 2003). These data highlight chemokines as dynamic biologic factors defining the host cell milieu throughout progression of A. actinomycetemcomitans pathogenesis.

Neutrophil interactions with the host and A. actinomycetemcomitans

Neutrophils (polymorphonuclear leukocytes/PMNs) are critical first responders to microbial pathogenic insult. Controlled PMN activation promotes non-oxidative proteins and reactive oxygen species (ROS) required to destroy pathogens (Miyasaki et al., 1986). Non-oxidative proteases include cathepsin G and elastase. Destructive effects of oxygen-derived free radicals were demonstrated by its depolymerization of hyaluronic acid and to a lesser extent proteoglycan, which are both constituents of extracellular matrix in the periodontium (Bartold et al., 1984). PMNs isolated from patients with aggressive periodontal disease with IgG titers against A. actinomycetemcomitans demonstrated greater PMN phagocytosis and killing compared to PMNs isolated from periodontally healthy control subjects (Guentsch et al., 2009). Relative to healthy control subjects, PMNs from aggressive periodontal disease patients were characterized by a significant increase in basal activity of human neutrophil elastase (Guentsch et al., 2009). In vitro, cathepsin G, a neutrophil-derived proteinase, had more bactericidal activity against A. actinomycetemcomitans than elastase (Miyasaki et al., 1991). With regards to the oxidative pathway, neutrophil phagocytosis of A. actinomycetemcomitans is associated with ROS, as indicated by the ability of A. actinomycetemcomitans to induce neutrophil activity by promoting ROS production (Guentsch et al., 2009; Permpanich et al., 2006). It was suggested that self-aggregating A. actinomycetemcomitans, possessing a rough fimbriated surface, impaired PMN phagocytosis, which perhaps is simply secondary to PMN limitations in engulfing large foreign bodies (Holm et al., 1993; Permpanich et al., 2006). Leukotoxin expression is another potential mechanism employed by A. actinomycetemcomitans to resist phagocytosis (Johansson et al., 2000). However contradictory reports concerning the role of leukotoxin expression levels in A. actinomycetemcomitans evasion by PMNs (Permpanich et al., 2006) call into question the role of leukotoxin as a virulence factor in host immune cell evasion.

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans also exhibits cytotoxic effects on PMNs. It has been reported that A. actinomycetemcomitans serotype b strains, including JP2, possess enhanced cytotoxicity against neutrophils (Permpanich et al., 2006). JP2, a highly studied serotype b strain, is characterized by excessive leukotoxin expression relative to other A. actinomycetemcomitans strains due to a 530-bp deletion mutation in the operon promoter region (Brogan et al., 1994). Another study reported that leukotoxin variability of A. actinomycetemcomitans strains did not affect PMNs ability to kill A. actinomycetemcomitans, and speculated that undefined A. actinomycetemcomitans virulence factors are responsible for strain associated variability in PMN cytotoxicity (Holm et al., 1993) Interestingly, extracellular supernatant was also cytotoxic, which was attributed to secreted leukotoxin (Permpanich et al., 2006). Based on the evasive and destructive nature of A. actinomycetemcomitans, studies have been conducted to determine the effects of antibiotics on PMNs ability to clear A. actinomycetemcomitans. Neutrophils with intracellular azithromycin accumulation demonstrated decreased A. actinomycetemcomitans survival (Lai et al., 2015). Taken together, the role of A. actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin expression in PMN phagocytosis evasion is unclear. Perhaps such inconsistencies in reported findings are a product of strain and serotype heterogeneity as well as inconsistent methodology (Permpanich et al., 2006).

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans ligands induce TLR signaling in macrophages

Macrophages are proven key players in A. actinomycetemcomitans pathogenesis. Monocytes enter the local tissue site of infection by diapedesis from the circulation where they differentiate into activated macrophages or osteoclasts. Surface toll-like receptors (TLRs) recognize pathogenic constituents and have been extensively studied in macrophage function. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans possesses endotoxic LPS, a potent agonist recognized by TLR2, TLR4, and TLR5 (Park et al., 2014), with TLR4 currently being considered the primary receptor for LPS.

Park et al. (2014) clearly delineated the function of TLR2 and TLR4 signaling in macrophage interactions with A. actinomycetemcomitans. When bone marrow derived murine macrophages from Tlr2−/− and Tlr4−/− mice were stimulated with A. actinomycetemcomitans, TLR2 and TLR4 deficient macrophages versus wild-type control macrophages, exhibited attenuated production of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6. Furthermore, double TLR2/4-deficient macrophages demonstrated a more prominent blunting of pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion. MyD88 is the adapter protein for all TLRs (except for TLR3), IL-1R, and IL-18R. MyD88 deficiency further reduced cytokine production by A. actinomycetemcomitans, suggesting that while TLR2 and TLR4 are critical regulators of A. actinomycetemcomitans induced inflammatory cytokine production, other receptors also propagate TNF-α and IL-6 production. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans also stimulated IL-12p40 (IL-12B) production in macrophages, which notably was also MyD88 dependent (Park et al., 2014). These findings clearly show that TLR signaling is critical for inflammatory cytokine formation, but that it is unclear how TLR4 and TLR2 dually interact with A. actinomycetemcomitans to modulate its perio-pathogenesis.

MAPK and NF-κB intracellular signaling in macrophages

Our project laboratory and other research groups have shown that MAPK and NF-κB signaling are largely involved in A. actinomycetemcomitans pathogenesis through pre-clinical rodent experimental periodontal disease models (Dunmyer et al., 2012; Li et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2011a). A consequence of TLR activation is regulation of intracellular signaling cascades. In murine derived macrophages, the cytoplasmic TLR adaptor protein, MyD88, was essential for A. actinomycetemcomitans induced phosphorylation of IkB-α, which promotes NF-kB activation, and all three MAPKS: p38, JNK, and ERK (Park et al., 2014). As shown in Fig. 2, A. actinomycetemcomitans LPS also led to phosphorylation of NF-κB subunits (p65 and p105) JNK, p38, and ERK MAPKs in rat macrophages (Li et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2011a).

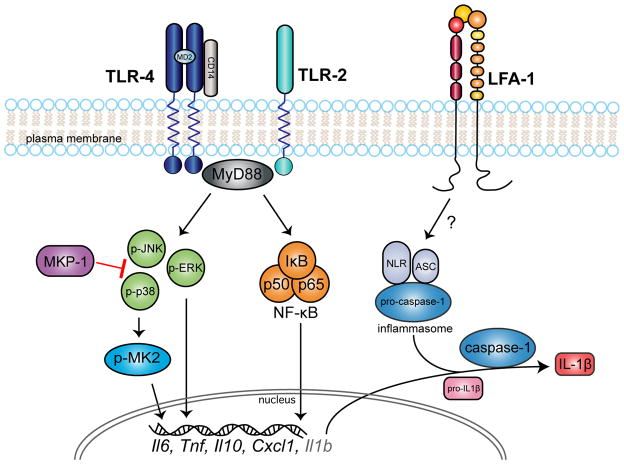

Figure 2. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans activates macrophage cell surface TLR2, TLR4, and LFA-1.

TLR2 and TLR4 activation initiates JNK, ERK, p38 MAPKs and NF-kB intracellular signaling cascades that regulate pro-inflammatory cytokine transcription. MKP-1 negatively controls MAPK signaling by dephosphorylating p-JNK and p-p38. p38 activation leads to MK2 phosphorylation as an intermediate kinase in cytokine production. LFA-1, which is a heterodimer of CD18 and CD11a, initiates the inflammasome complex consisting of NLRs, ASC, and pro-caspase 1. Once activated, caspase-1 cleaves pro-IL-1β into mature IL-1β cytokine.

We have elaborated on the involvement of MAPK cascade proteins, MAPK-activated protein kinase 2 (MK2) and MAPK-phosphatase (MKP)-1 in A. actinomycetemcomitans pathogenesis. MK2 is a phosphorylation substrate of p38α/β MAPK that is activated by A. actinomycetemcomitans and A. actinomycetemcomitans LPS in macrophages (Dunmyer et al., 2012; Li et al., 2011). Attenuation of MK2 in a rat oral LPS injection model led to decreased inflammatory infiltrate and bone loss, proving that MK2 is essential for upregulating the host response (Li et al., 2011; Rogers et al., 2007). We also investigated the role of MKP-1, an anti-inflammatory phosphatase that dampens the immune response in a similar rat model (Yu et al., 2011a). MKP-1, primarily responsible for dephosphorylation of phospho(p)-p38 and p-JNK, down regulated cytokine production of IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10, and CXCL1 in macrophages. MKP-1 also decreased inflammatory infiltration in vivo (Yu et al., 2011a). Conversely, when MKP-1 was over-expressed in the same rat model, histological findings were similar to when MK2 was down-regulated (Li et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2011a).

In addition to MAPK cytokine modulation, RNA binding proteins tristetraprolin (TTP) and AUF-1 post-transcriptionally destabilize pro-inflammatory cytokines activated by A. actinomycetemcomitans. Activation of the p38/MK2 axis leads to phosphorylation of TTP (Chrestensen et al., 2004). Under normal conditions, TTP binds to AU rich elements (ARE) in cytokine mRNA transcripts, such as IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10, IL-8, and PGE2, subsequently promoting mRNA degradation (Palanisamy et al., 2012). Upon phosphorylation by activation of the p38/MK2 axis, TTP can no longer bind to the ARE, which increases cytokine translation. One study showed that TTP over expression in macrophages dampened LPS-induced inflammatory cytokine production of TNF-α, IL-6, and PGE2 (Patil et al., 2008). MKP-1 overexpression stimulated with A. actinomycetemcomitans LPS showed activation of AUF-1 and destabilization of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10 transcripts (Yu et al., 2011b). Taken together activation of MAPK signaling through intermediate pathways is an essential regulator of LPS actions driving pro-inflammatory cytokine responses.

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans induces inflammasome pathways in monocytes

Leukotoxin and CDT are inducers of the inflammasome pathway that stimulates cleavage of pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their respective activated forms. Leukotoxin initiated IL-1β and IL-18 production in monocytes via a caspase-1 dependent pathway (Kelk et al., 2011; Kelk et al., 2003). Caspase 1 enzymatically cleaves pro-IL-1β into biologically active IL-1β at an inflammasome complex partially composed of nod like receptor proteins (NLRPs) in monocytes (Thornberry et al., 1992). In particular A. actinomycetemcomitans stimulated NLRP3 gene expression (Belibasakis et al., 2012; Okinaga et al., 2015). More recent studies show that A. actinomycetemcomitans (serotype a) elicited NLRP3 and conversely attenuated NLRP6 gene expression ultimately leading to a significant increase in IL-1β secretion in human mononuclear leukocytes (Belibasakis et al., 2012). Interestingly, this aforementioned study showed that IL-1β secretion was independent of the A. actinomycetemcomitans virulence factors, CDT and leukotoxin (Belibasakis et al., 2012). Conversely, CDT induced IL-1β and IL-18 secretion via inflammasome proteins NLRP3, adaptor protein ASC, caspase-1, ROS, extracellular ATP, and K+ in a monocyte cell line (Shenker et al., 2015). A proposed model for leukotoxin inducing IL-1β and IL-18 secretion involves leukotoxin forming pores in the cell membrane that cause ATP to leak and activate the P2X7 on the extracellular surface (Haubek et al., 2014; Kelk et al., 2011). This facilitates an influx of K+ that activates the inflammasome complex leading to mature IL-1β and IL-18 secretion (Haubek et al., 2014; Kelk et al., 2011).

Nevertheless, there is conflicting evidence as to whether A. actinomycetemcomitans induction of IL-1β secretion is inflammasome dependent. Contradictory findings reported by another recent investigation demonstrated that inhibition of cathepsin B and ROS attenuated A. actinomycetemcomitans (serotype b) mediated IL-1β secretion, whereas inhibition of NLRP3 and caspase-1 had no effect (Okinaga et al., 2015). Taking into consideration that ROS are potent inducers of the inflammasome pathway, it is plausible that in the aforementioned study siRNA mediated partial and incomplete knockdown of NLRP3 and caspase-1 resulting in IL-1β expression (Okinaga et al., 2015). These recent conflicted findings concerning A. actinomycetemcomitans regulatory mechanisms impacting IL-1β secretion imply that A. actinomycetemcomitans actions may be strain and/or immune cell dependent. Inflammasome related ROS, NLRP, and caspase-1 are key players in vitro during A. actinomycetemcomitans stimulation of IL-1β (Fig. 2).

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans controls macrophage cell cycle and apoptosis

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans has a dual function in host evasion via virulence actions causing cell cycle arrest and promoting apoptosis. A. actinomycetemcomitans CDT was capable of binding to the cell surface of a human monocyte cell line and inducing cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase (Mise et al., 2005). A more recent study suggested that the intracellular JAK2/STAT3 signaling axis was essential for causing cell cycle arrest in the G1 cell cycle phase. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans induced activation of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway, which controls cell proliferation in mouse monocyte/macrophage RAW276.4 cells leads to a decrease in cell cycle (Okinaga et al., 2013). Overexpression of SOC3 normalized cell cycle in the A. actinomycetemcomitans treated cells via down-regulating the JAK2/STAT3 axis (Okinaga et al., 2013). These findings suggest a critical role for A. actinomycetemcomitans in cell cycle arrest throughout phases of the cell cycle that may be promoted by different virulence factors or signaling pathways.

Leukotoxin is considered the main component that induces monocyte cell death. Relative to cells lacking human CD18, leukotoxin increased cytotoxicity in mammalian leukemia cell lines expressing CD18 (Dileepan et al., 2007). Taking into account that CD18 is a subunit of LFA-1 (CD18/CD11b), the mechanism by which leukotoxin induces monocyte cell death was studied in human monocyte leukemia cell lines (THP-1, HL-60) and the human erythromyeloidblastoid leukemia cell line lacking LFA-1 expression (K562) (Kaur et al., 2014). This study revealed that leukotoxin stimulated cofilin dephosphorylation, actin depolymerization, internalization of leukotoxin, and ultimate lysosomal mediated cell death that is dependent on LFA-1 (Kaur et al., 2014). CD14, a TLR4 co-receptor, was also crucial for the presence of intracellular A. actinomycetemcomitans that caused DNA fragmentation and monocyte apoptosis (Muro et al., 1997). Moreover, poly-N-acteylglucosamine (PGA), an A. actinomycetemcomitans exopolysaccharide, enhanced colonization (Shanmugam et al., 2015), biofilm formation (Izano et al., 2008), and decreased monocyte viability (Venketaraman et al., 2008). Thus, monocyte surface receptors, LFA-1 and CD14, mediate A. actinomycetemcomitans internalization that ultimately may result in monocyte apoptosis.

Dendritic cells and the antigen response

Dendritic cells (DCs) are critical antigen presenting cells responsible for activating and driving T-cell differentiation. One study demonstrated that monocytes isolated from patients with localized aggressive periodontitis differentiated spontaneously into CD11c+ DCs in vitro (Barbour et al., 2002). Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans was the most potent inducer of IL-12p70 (a Th1 inducer) production from DCs when compared to other pathogenic bacteria, Escherichia coli and Porphyromonas gingivalis (Kikuchi et al., 2004). Like macrophages, DCs possess TLRs equipped to respond to pathogenic signals. IL-12p70 was regulated by TLR4 in DCs when activated with A. actinomycetemcomitans LPS (Kikuchi et al., 2004).

In a separate study conducted by Diaz-Zuniga et al. (2015b), peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated from healthy individuals were differentiated into DCs in vitro. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans serotypes a, b or c were employed to elucidate serotype-specific actions in TLR2 versus TLR4 dependent stimulation of chemokine receptor expression and cytokine secretion. Interestingly, all serotypes induced TLR4 gene expression, but serotype b more significantly induced TLR2 expression than serotypes a and c. Furthermore, serotype b also more preferentially elicited IL-12, IL-1β, and IL-23 protein secretion as well as CCR5 and CCR6 gene expression. IL-12, IL-23, and CCR6 gene expression proved to be solely regulated by TLR2 signaling independent of TLR4 (Diaz-Zuniga et al., 2015b). Thus, A. actinomycetemcomitans is clearly capable of triggering DC functions through TLR2 and TLR4, which is similar to TLR signaling in macrophages described previously.

Are mast cells involved in A. actinomycetemcomitans pathogenesis?

There is limited knowledge about the function of myeloid derived mast cells (MCs) with regards to periodontal disease. In general MCs contain granules of histamine, proteoglycans, and proteinases that are released from the cells in response to a stimulus. These cells can also secrete pro-inflammatory TNF-α, nitric oxide (NO) (Bidri et al., 1997), and fibroblast growth factor (Qu et al., 1995). MCs were increased in periodontal disease tissues from patients with localized chronic periodontal disease (Batista et al., 2005). No known studies have been conducted to assess infiltration or function of mast cells in aggressive periodontal disease. With regards to A. actinomycetemcomitans, a single in vitro study concluded that mouse MCs were able to phagocytize non-opsonized A. actinomycetemcomitans (Lima et al., 2013). The current lack of published studies explaining the role of MCs suggests these cells are either not playing a critical role in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease or are alternatively being overlooked.

Lymphoid-derived B and T cells respond to A. actinomycetemcomitans

T and B lymphocytes are both found in periodontal lesions (Lin et al., 2011; Page et al., 1976). For the purpose of this review, B, T, and Natural Killer (NK) cells are considered lymphoid-derived cells, although NK cells are unique in that they have been differentiated from myeloid progenitors (Grzywacz et al., 2011). Early literature reported conflicting evidence about CD4+/CD8+ T lymphocyte ratio imbalance in juvenile and rapidly progressing periodontal disease states (Kinane et al., 1989; Nagasawa et al., 1995). Lymphocytes have been implicated to play an integral role in adaptive immune responses directly associated with A. actinomycetemcomitans pathogenesis (Lin et al., 2011; Underwood et al., 1993). NK cells, a cytotoxic lymphocyte, were critical for DC-induced IFN-γ production by peripheral blood cells secondary to A. actinomycetemcomitans treatment (Kikuchi et al., 2004).

Li et al. (2010) reported activation of the adaptive immune response in a rat periodontal disease model induced by A. actinomycetemcomitans feeding. The investigators recovered CD45RA+ B and CD4+ T cells from draining cervical and submandibular lymph nodes. In the A. actinomycetemcomitans exposed treatment groups, activated B cells, defined by the antigen presenting cell marker, MHC Class II, were also increased. The gene profile of B cells demonstrated transcriptional upregulation of bone morphogenic proteins, whereas T cells were characterized by induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines and RANKL the pro-resorptive cytokine required for osteoclast formation and resorptive function (Li et al., 2010).

Earlier literature reported that serum antibodies against A. actinomycetemcomitans having opsonic capabilities and the potential to promote A. actinomycetemcomitans phagocytosis were detectable in patients with localized juvenile periodontitis (Baker et al., 1989), indicating that plasma cells (mature B cells) actively secrete antibodies against A. actinomycetemcomitans during infection. Furthermore, monocytes control IgG2a antibody production (Ishihara et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 1996), which is in line with T and B cell activation by A. actinomycetemcomitans in advanced stages of periodontal disease progression.

Polarizing effects of A. actinomycetemcomitans on Helper T cells

While Th cells are delineated into 5 subsets (Th1, 2, 9, 17, and 22), historical theory emphasizes the ratio of Th1/Th2 as the critical regulator of periodontal disease progression, but has resulted in a poor understanding of the Th cell subsets in A. actinomycetemcomitans associated perio-pathogenesis. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans CdtB (part of the CdtA,B,C holocomplex) and LtxA induced CD4+ lymphocyte cell proliferation in vitro (Schreiner et al., 2013). Th1 cells typically secrete IFN-γ and are classically induced by IL-12 (p70), a heterodimer of IL-12A (p35) and IL-12B (p40) (Trinchieri, 2003). Th17 cells are a pro-inflammatory Th subset that secrete high levels of IL-17 and are polarized by IL-23, which shares the IL-12B subunit with IL-12 (Trinchieri et al., 2003). More recently, it has been suggested that the Th1/Th2 paradigm in periodontal disease studies should be shifted to Th1/Th2/Th17 cells due to the vast amount of research known about Th17 cells in other diseases, such as arthritis (Gaffen et al., 2008; Kramer et al., 2007). A recent publication suggested that the Th phenotype is serotype dependent, and Th17 polarization occurs in response to A. actinomycetemcomitans (Diaz-Zuniga et al., 2015a). DCs treated with whole A. actinomycetemcomitans or isolated LPS from serotypes a-c used to stimulate CD4+ T cells showed that serotype b induced the most robust Th1 and Th17 response (Diaz-Zuniga et al., 2015a). This indicates that A. actinomycetemcomitans serotype b has the most pro-inflammatory potential A heat shock protein, GroEL, derived from A. actinomycetemcomitans, was also capable of polarizing human peripheral blood cells into Th1-type CD4+ cells that produce both IFN-γ and IL-10 (Saygili et al., 2012).

On the other hand, Th2 cells secrete IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans induced IL-10 and IL-4, which promotes Th2 polarization (Kikuchi et al., 2004). Unlike pro-inflammatory Th1 and Th17 cells, Th2 and Treg cells are immunosuppressive in nature. A recent timely study by Araujo-Pires et al. (2015) clearly defined Treg migration in an A. actinomycetemcomitans murine model. Interestingly, CCR4 proved to regulate Th2 (CD4+IL4+) and Treg (CD4+FOXp3+) cell infiltration secondary to mouse oral A. actinomycetemcomitans inoculation (Araujo-Pires et al., 2015). Furthermore, CCR4-deficient mice, IL-4 deficient mice, and mice blocked against CCL22, had decreased Tregs, enhanced inflammatory infiltrate, and exacerbated periodontal bone loss (Araujo-Pires et al., 2015).

Another study suggested that CCL22, a CCR4 ligand, preferentially increased Treg associated mRNA levels of FOXp3, IL-10, and TGF-β, but not Th2-assocated IL-4 during A. actinomycetemcomitans infection (Glowacki et al., 2013). Deficiencies in CCR4, IL-4, and CCL22 led to a similar cytokine profile with significant increases in pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-17, and RANKL, and decreases in anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10, TGF-β, and OPG (Araujo-Pires et al., 2015). These two murine experimental periodontitis studies demonstrated that IL-4 cytokine and CCL22/CCR4 chemokine signaling are critical regulators of Treg migration, suppression of inflammation, and attenuation of periodontal bone loss in A. actinomycetemcomitans mediated periodontal disease progression. The T cell milieu is composed of classically considered pro- and anti-inflammatory T cell subsets that respond to A. actinomycetemcomitans. While the mechanisms of Th2/Treg subsets during A. actinomycetemcomitans pathogenesis were eloquently studied in vivo, Th1/Th17 mechanistic responses have been mostly been studied in vitro.

III. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans osteoimmuno-modulatory actions alter bone remodeling processes, having catabolic effects on alveolar bone homeostasis

In a longitudinal study, 91.7% of subjects presenting with vertical periodontal bone loss detected by radiograph were A. actinomycetemcomitans positive, highlighting the destructive pathologic impact of A. actinomycetemcomitans on the alveolar bone complex (Fine et al., 2013). Under physiological conditions, bone remodeling/turnover is a coupled cellular process in which balanced osteoclast-osteoblast actions renew the bone matrix, supporting skeletal tissue homeostasis in health. Alveolar bone remodeling takes place within small foci and occurs in the following sequence: Activation-Resorption-Reversal-Formation (Baron, 1973; 1977). The seminal work that defined the impact of periodontal disease on alveolar bone remodeling in the golden hamster, elucidated that periodontal disease causes net alveolar bone loss via disruption/uncoupling of normal alveolar bone remodeling processes (Baron et al., 1978). Notably, it was clearly shown that periodontal disease induces catabolic effects on alveolar bone homeostasis that are secondary to not only an increase in bone resorption, but also a decrease in bone formation (Baron et al., 1978). Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans LPS, LtxA, and to a lesser extent CdtB, PGA, and OMP29 are virulence factors that have been shown to promote bone loss in pre-clinical rat models (Li et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2011; Rogers et al., 2007; Schreiner et al., 2013; Shanmugam et al., 2015; Yu et al., 2011a).

RANKL signaling regulates alveolar bone loss during pathogenesis

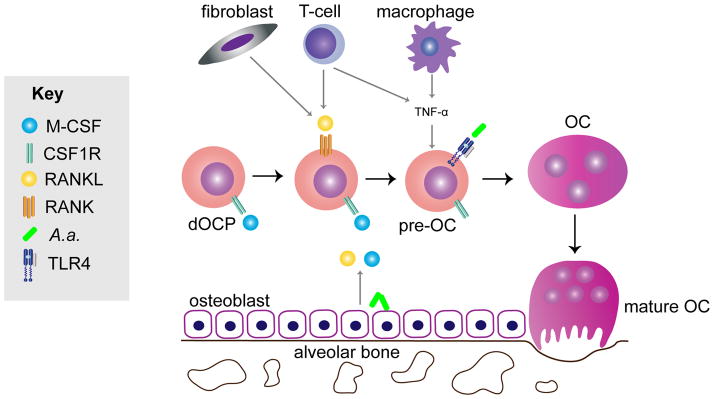

RANKL is an essential cytokine in osteoclast formation and resorptive function contributing to bone loss. This mechanism is fine-tuned by the RANKL decoy receptor osteoprotegerin (OPG), which blocks RANKL signaling through its cognate receptor, RANK. The imbalance of the RANKL/OPG ratio is thought to deregulate bone remodeling, driving bone loss when RANKL concentrations exceed OPG relative to normal physiology (Boyce et al., 2008). RANKL is expressed as a surface molecule mainly on fibroblasts, osteoblasts, and T cells, but can also be secreted locally into the extracellular matrix and is found in circulation. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans indirectly regulates osteoclast formation through inducing RANKL expression by non-osteoclastic cells thereby stimulating RANK on dOCPs to form mature osteoclasts. RANKL binding activates NFATc1, which is the considered the master transcription factor of osteoclastogenesis (Kim et al., 2005). However, inflammatory chemokines and cytokines are also known to directly induce osteoclast formation independent of RANKL (Ha et al., 2011; Hotokezaka et al., 2007; Valerio et al., 2014). Thus RANKL-RANK signaling and pro-inflammatory cytokines drive osteoclastogenesis (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. M-CSF release from osteoblasts lining alveolar bone stimulates defined osteoclast progenitors (dOCPs) to express the RANK receptor in preparation for a RANKL signaling response.

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans stimulates RANKL, which is on the cell surface and secreted by osteoblasts, T-cells, and fibroblasts differentiates dOCPs into mononuclear pre-osteoclasts (pre-OCs) that are pushed toward the osteoclast (OC) lineage. Amid RANKL signaling, in the micro-environment pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α additively stimulates formation of TRAP positive multinucleated functional OCs. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans LPS also stimulates OC formation. Combined these A. actinomycetemcomitans –induced drivers of OC formation lead to mature OC formation and subsequent alveolar bone loss.

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans increases RANKL expression in the local inflammatory microenvironment by indirect mechanisms. More specifically, CDT, LPS, and outer membrane protein (OMP) 29 have been shown to stimulate RANKL expression (Belibasakis et al., 2005a; Lin et al., 2011; Wada et al., 2004). One study showed that A. actinomycetemcomitans induced RANKL mRNA expression in human gingival fibroblasts independent of TNF, IL-1β, and Il-1R (Belibasakis et al., 2005b). CDT upregulated RANKL on gingival fibroblasts and PDL cells (Belibasakis et al., 2005a). Additionally, A. actinomycetemcomitans activates T lymphocytes, which express RANKL to further, promote osteoclastogenesis. Using a co-culture system, surface RANKL on T-cells primed with A. actinomycetemcomitans-derived OMP29 was essential for osteoclastogenesis (Lin et al., 2011). Most recently, Tregs have been demonstrated to blunt RANKL mediated periodontal bone loss (Araujo-Pires et al., 2015).

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans endotoxins can also promote osteoclast formation by direct interactions with dOCPs or monocyte osteoclast precursors. LPS and TNF-α activated p38/JNK MAPKs and directly induced osteoclast formation from the mouse macrophage/monocyte leukemia cell line, RAW264.7 (Hotokezaka et al., 2007). In the A. actinomycetemcomitans LPS rat injection model published from our project laboratory, MK2 attenuation decreased the number of TRAP positive osteoclast cells, whereas MKP-1 overexpression also decreased osteoclast formation and maxillary alveolar bone loss caused by A. actinomycetemcomitans LPS (Li et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2011a). Interestingly, MK2 inhibition also significantly blunted IL-1β gene expression in A. actinomycetemcomitans LPS treated macrophages (Li et al., 2011). IL-1 receptor (R) antagonist, which competes with IL-1β and IL-1α for binding to inhibit IL-1R signaling, proved to be critical for down-regulating osteoclast formation and bone loss secondary to mouse LPS challenge (Izawa et al., 2014). These results suggest that LPS induction of the IL-1R axis is a critical regulator of bone loss. Furthermore, in a rat calvarial model, whole A. actinomycetemcomitans induced osteoclast and resorption pit formation (Dunmyer et al., 2012).

To better understand the role of MAPK signaling in osteoclastogenesis, our project laboratory first showed that A. actinomycetemcomitans LPS promoted osteoclast formation from murine dOCPs in vitro (Valerio et al., 2014). In this same study, we found that MKP-1 signaling through chemokines CXCL1 and CXCL2 dampened LPS-induced osteoclast formation (Valerio et al., 2014). We have previously shown that A. actinomycetemcomitans LPS signals through MK2 and regulates CXCL1 gene expression (Li et al., 2011). Since TTP overexpression during LPS challenge led to attenuation of bone loss (Patil et al., 2008), a possible mechanism for MK2/TTP regulation of bone loss is by CXCL1 mRNA stability (Datta et al., 2008). Based on these findings, it appears that both direct and indirect signaling mechanisms of stimulation promote mature osteoclast formation in the presence of A. actinomycetemcomitans (Fig. 3).

Bone resorption by host matrix metalloproteinase and A. actinomycetemcomitans collagenase

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) are expressed by many cell types, including monocytes, fibroblasts, and osteoclasts, all of which play a role in A. actinomycetemcomitans perio-pathogenesis. MMPs are enzymes that degrade collagen and solubilize matrix. Similar to the inhibiting action of OPG against RANKL signaling, TIMPs nonspecifically regulate MMPs (Baker et al., 2002). MMP-13 is expressed in oral cell types, dental pulp cells, and PDL fibroblasts (Rossa et al., 2005; Suri et al., 2008). Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans induced MMP-1,−2, and −9 expression in a murine infection model and was followed by upregulation of TIMP genes (Garlet et al., 2006). Furthermore, secreted MMP-1, −3, and −9 and TIMP-1 were activated by A. actinomycetemcomitans LPS in human peripheral blood monocytes (Serra et al., 2010). Monocytes adjacent to the alveolar bone have the potential to form osteoclasts in the periodontal microenvironment. Osteoclasts respond to MMPs and have MMP activity by promoting osteoclast migration (Engsig et al., 2000; Sato et al., 1998). Interestingly, A. actinomycetemcomitans can bind to saliva coated hydroxyapatite, the main constituent of dentoalveolar tissues (Kagermeier et al., 1985; Rosan et al., 1988), and has been shown to have bone-degrading collagenase activity (Robertson et al., 1982). Taken together, it is highly evident that A. actinomycetemcomitans has catabolic osteo-immunomodulatory actions promoting bone loss.

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans impairs osteoblastogenesis

Early studies assessing A. actinomycetemcomitans effects on bone formation revealed that A. actinomycetemcomitans is a potent inhibitor of bone collagen synthesis (Harvey et al., 1986; Meghji et al., 1992; Wilson et al., 1988). It was demonstrated that LPS purified from A. actinomycetemcomitans, at a concentration of 1 ug/ml in mouse calvaria explant cultures inhibits DNA and collagen synthesis by 30% and 40% (Harvey et al., 1986). A subsequent ex vivo mouse calvaria explant culture study performed by the same research group showed that isolated capsular material, free of LPS, significantly blunted synthesis of DNA and collagen at concentrations as low as 10 ng/ml (Wilson et al., 1988). A follow-up investigation, evaluating the direct effect of A. actinomycetemcomitans derived LPS versus surface associated material on murine calvaria-derived osteoblastic cells, elucidated that A. actinomycetemcomitans virulence factors directly impair osteoblast proliferation and collagen synthesis (Meghji et al., 1992).

Li et al. (2012) conducted a single investigation of A. actinomycetemcomitans LPS actions on osteoblast differentiation highlighting that A. actinomycetemcomitans LPS has a concentration dependent, inverse regulatory impact on osteoblastic cell differentiation. The noted study was an in vitro investigation assessing the impact of A. actinomycetemcomitans derived LPS on bone sialoprotein (BSP), a marker of osteoblast differentiation, in the osteoblast-like ROS17/2.8 cell line. Interestingly, 0.1 ug/mL LPS suppressed and 0.01 ug/mL LPS enhanced BSP gene transcription, which occurred via heterogeneous signaling pathways mediated through CRE, FRE, and HOX elements in the rat BSP gene promoter (Li et al., 2012). In vitro and ex vivo osteoblast studies focus on A. actinomycetemcomitans LPS dosage dependent responses on osteoblast differentiation.

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans promotes osteoblast apoptosis

Investigations of A. actinomycetemcomitans inhibitory effects on osteoblastogenesis revealed that A. actinomycetemcomitans elicited apoptosis in osteoblastic cells through its multifactorial virulence mechanisms. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans capsular-like polysaccharide antigen (CPA) from serotype c (CPA-c) inhibited osteoblast cell line proliferation via a pro-apoptotic mechanism (Yamamoto et al., 1999). These results indicated that CPA-c mediated apoptosis of MC3T3-E1 murine osteoblastic cells via the Fas system, independent of Bcl-2 or NO synthase (Yamamoto et al., 1999). To the contrary of A. actinomycetemcomitans CPA-c mechanisms driving apoptosis in osteoblasts, A. actinomycetemcomitans derived LPS induced production of NO in the HOS human osteoblastic cell line (Sosroseno et al., 2009), which suggests that LPS may contribute to A. actinomycetemcomitans pro-apoptotic actions on osteoblastic cells via NO signaling.

Taking into consideration clinical studies reporting ultra-structural findings which imply that localized aggressive periodontitis is associated with bacterial invasion of the alveolar bone surface (Carranza et al., 1983), it is conceivable that the inflammasome protein, NLRP3, is a critical regulator of A. actinomycetemcomitans induced osteoblast apoptosis (Zhao et al., 2014). Zhao et al. (2014) infected isolated human osteoblastic MG63 cell cultures with A. actinomycetemcomitans, which increased cell apoptosis. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans infection upregulated the expression of inflammatory mediators downstream of the NLRP3 inflammasome protein, and knockdown expression of NLRP3 by siRNA attenuated apoptosis of A. actinomycetemcomitans infected MG63 osteoblastic cells (Zhao et al., 2014). While the aforementioned study does not elucidate the role of specific A. actinomycetemcomitans virulence factors, findings from this in vitro investigation highlight that A. actinomycetemcomitans invasion of the alveolar bone surface may directly promote osteoblast apoptosis through the NLRP3 inflammasome (Zhao et al., 2014). Furthermore, Teng and Hu (2003) identified a novel gene, the CagE homologue of A. actinomycetemcomitans, which encodes a protein associated with the bacterial type IV secretion system. Serum immune studies, demonstrating recognition in A. actinomycetemcomitans infected periodontitis subjects but not periodontally healthy control subjects, support CagE’s contributory role in A. actinomycetemcomitans associated periodontal tissue destruction. Notably, the secreted CagE protein significantly induced apoptosis in isolated human primary osteoblastic cell cultures (Teng et al., 2003).

The reviewed body of limited published works elucidating the inhibitory impact of A. actinomycetemcomitans on osteoblastogenesis highlights the need for future investigations defining the role of A. actinomycetemcomitans virulence factor mechanisms in the regulation of osteoblastic cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, bone matrix formation, and mineralization. Baron and Saffar’s (1978) seminal experimental periodontitis - alveolar bone remodeling investigation, clearly demonstrated that net alveolar bone loss in periodontal disease is secondary to both increased osteoclastogenesis mediated bone resorption and decreased osteoblastogenesis mediated bone formation. However, researchers have focused on osteoclastogenesis and neglected the study of periodontitis effects on osteoblastic cells. While future studies are needed, it has been realized that A. actinomycetemcomitans impairs osteoblastogenesis. Periodontal researchers must embrace that A. actinomycetemcomitans induced alveolar bone loss is not solely caused by increased osteoclastogenesis mediated bone resorption, but rather is secondary to altered bone remodeling, a process which is dynamically mediated by both osteoclastic and osteoblastic cell actions.

Concluding remarks

A review of the literature showed that many non-hematopoietic and hematopoietic cell types contribute to pathogenesis of A. actinomycetemcomitans. While numerous signaling pathways and host response mechanisms have been divulged through pre-clinical animal models, many facets of the host response are not well understood. We observed that a majority of known mechanisms of A. actinomycetemcomitans pathogenesis are limited to in vitro findings. Interestingly, there is an overwhelming majority of experimental studies in hematopoietic cells compared to non-hematopoietic lineages, which are entirely limited to in vitro findings. The field could benefit from applying modern murine transgenic/knockout pre-clinical models to further elucidate immunomodulatory effects of A. actinomycetemcomitans on non-hematopoietic or hematopoietic immune response cells.

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans induces the activation of MAPK signaling pathways in several cell types, increasing pro-inflammatory cytokines and cell apoptosis. Chemokines are elevated during A. actinomycetemcomitans infection, which appears to be an integral contributor to the recruitment and expansion of host immune cell response mediating the A. actinomycetemcomitans induced periodontal disease state. We identified major gaps in knowledge in macrophage and T cell polarization and osteoblast signaling during A. actinomycetemcomitans progression. It is also unclear whether A. actinomycetemcomitans alone can stimulate osteoclastogenesis and/or inhibit osteoblastogenesis. Indeed, it appears the host immune response mechanisms demonstrated thus far are not only cell-type dependent but also A. actinomycetemcomitans strain and serotype-specific.

References

- Ahmed HJ, Svensson LA, Cope LD, et al. Prevalence of cdtABC genes encoding cytolethal distending toxin among Haemophilus ducreyi and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans strains. J Med Microbiol. 2001;50:860–864. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-50-10-860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antony B, Thomas S, Chandrashekar SC, Kumar MS, Kumar V. Osteomyelitis of the mandible due to Aggregatibacter (Actinobacillus) actinomycetemcomitans. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52:115–116. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.44994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo-Pires AC, Vieira AE, Francisconi CF, et al. IL-4/CCL22/CCR4 axis controls regulatory T-cell migration that suppresses inflammatory bone loss in murine experimental periodontitis. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30:412–422. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arirachakaran P, Apinhasmit W, Paungmalit P, Jeramethakul P, Rerkyen P, Mahanonda R. Infection of human gingival fibroblasts with Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans: An in vitro study. Arch Oral Biol. 2012;57:964–972. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:1–6. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assuma R, Oates T, Cochran D, Amar S, Graves DT. IL-1 and TNF antagonists inhibit the inflammatory response and bone loss in experimental periodontitis. J Immunol. 1998;160:403–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker AH, Edwards DR, Murphy G. Metalloproteinase inhibitors: biological actions and therapeutic opportunities. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:3719–3727. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker PJ, Wilson ME. Opsonic IgG antibody against Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in localized juvenile periodontitis. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1989;4:98–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1989.tb00106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandhaya P, Saraithong P, Likittanasombat K, Hengprasith B, Torrungruang K. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans serotypes, the JP2 clone and cytolethal distending toxin genes in a Thai population. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39:519–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2012.01871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour SE, Ishihara Y, Fakher M, et al. Monocyte differentiation in localized juvenile periodontitis is skewed toward the dendritic cell phenotype. Infect Immun. 2002;70:2780–2786. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.6.2780-2786.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R. Remaniement de l’os alveolaire et des fibres desmodontales au cours de la migration physiologique. J Biol Buccale. 1973;1:151–170. [Google Scholar]

- Baron R. Importance of the intermediate phases between resorption and formation in the measurement and understanding of the bone remodeling sequence. In: Meunier PJ, editor. Bone Histomorphometry: Second International Workshop; Toulouse, France: Lyon Armour Montagu; 1977. pp. 179–183. [Google Scholar]

- Baron R, Saffar JL. A quantitative study of bone remodeling during experimental periodontal disease in the golden hamster. J Periodontal Res. 1978;13:309–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1978.tb00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartold PM, Wiebkin OW, Thonard JC. The effect of oxygen-derived free radicals on gingival proteoglycans and hyaluronic acid. J Periodontal Res. 1984;19:390–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1984.tb01012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista AC, Rodini CO, Lara VS. Quantification of mast cells in different stages of human periodontal disease. Oral Dis. 2005;11:249–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belibasakis GN, Johansson A. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans targets NLRP3 and NLRP6 inflammasome expression in human mononuclear leukocytes. Cytokine. 2012;59:124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belibasakis GN, Johansson A, Wang Y, Chen C, Kalfas S, Lerner UH. The cytolethal distending toxin induces receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand expression in human gingival fibroblasts and periodontal ligament cells. Infect Immun. 2005a;73:342–351. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.1.342-351.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belibasakis GN, Johansson A, Wang Y, et al. Cytokine responses of human gingival fibroblasts to Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans cytolethal distending toxin. Cytokine. 2005b;30:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidri M, Ktorza S, Vouldoukis I, et al. Nitric oxide pathway is induced by Fc epsilon RI and up-regulated by stem cell factor in mouse mast cells. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2907–2913. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce BF, Xing L. Functions of RANKL/RANK/OPG in bone modeling and remodeling. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;473:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brogan JM, Lally ET, Poulsen K, Kilian M, Demuth DR. Regulation of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin expression: analysis of the promoter regions of leukotoxic and minimally leukotoxic strains. Infect Immun. 1994;62:501–508. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.501-508.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bueno LC, Mayer MP, DiRienzo JM. Relationship between conversion of localized juvenile periodontitis-susceptible children from health to disease and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin promoter structure. J Periodontol. 1998;69:998–1007. doi: 10.1902/jop.1998.69.9.998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carranza FA, Jr, Saglie R, Newman MG, Valentin PL. Scanning and transmission electron microscopic study of tissue-invading microorganisms in localized juvenile periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1983;54:598–617. doi: 10.1902/jop.1983.54.10.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang CY, Kyritsis G, Graves DT, Amar S. Interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor activities partially account for calvarial bone resorption induced by local injection of lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4231–4236. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.4231-4236.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrestensen CA, Schroeder MJ, Shabanowitz J, et al. MAPKAP kinase 2 phosphorylates tristetraprolin on in vivo sites including Ser178, a site required for 14-3-3 binding. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10176–10184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310486200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christersson LA, Slots J, Rosling BG, Genco RJ. Microbiological and clinical effects of surgical treatment of localized juvenile periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1985;12:465–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1985.tb01382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuende E, de Pablos M, Gomez M, Burgaleta S, Michaus L, Vesga JC. Coexistence of pseudogout and arthritis due to Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:657–658. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.3.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, Biswas R, Novotny M, et al. Tristetraprolin regulates CXCL1 (KC) mRNA stability. J Immunol. 2008;180:2545–2552. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Zuniga J, Melgar-Rodriguez S, Alvarez C, et al. T-lymphocyte phenotype and function triggered by Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans is serotype-dependent. J Periodontal Res. 2015a doi: 10.1111/jre.12270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Zuniga J, Monasterio G, Alvarez C, et al. Variability of the dendritic cell response triggered by different serotypes of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans or Porphyromonas gingivalis is toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) or TLR4 dependent. J Periodontol. 2015b;86:108–119. doi: 10.1902/jop.2014.140326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson BC, Moffatt CE, Hagerty D, et al. Interaction of oral bacteria with gingival epithelial cell multilayers. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2011;26:210–220. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2011.00609.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dileepan T, Kachlany SC, Balashova NV, Patel J, Maheswaran SK. Human CD18 is the functional receptor for Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin. Infect Immun. 2007;75:4851–4856. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00314-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunmyer J, Herbert B, Li Q, et al. Sustained mitogen-activated protein kinase activation with Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans causes inflammatory bone loss. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2012;27:397–407. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2012.00656.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engsig MT, Chen QJ, Vu TH, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase 9 and vascular endothelial growth factor are essential for osteoclast recruitment into developing long bones. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:879–889. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.4.879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabris AS, DiRienzo JM, Wikstrom M, Mayer MP. Detection of cytolethal distending toxin activity and cdt genes in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans isolates from geographically diverse populations. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2002;17:231–238. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-302x.2002.170405.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine DH, Markowitz K, Fairlie K, et al. A consortium of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, Streptococcus parasanguinis, and Filifactor alocis is present in sites prior to bone loss in a longitudinal study of localized aggressive periodontitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:2850–2861. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00729-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine DH, Markowitz K, Furgang D, et al. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha: a salivary biomarker of bone loss in a longitudinal cohort study of children at risk for aggressive periodontal disease? J Periodontol. 2009;80:106–113. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine DH, Markowitz K, Furgang D, et al. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and its relationship to initiation of localized aggressive periodontitis: longitudinal cohort study of initially healthy adolescents. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3859–3869. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00653-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fives-Taylor PM, Meyer DH, Mintz KP, Brissette C. Virulence factors of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Periodontol 2000. 1999;20:136–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1999.tb00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffen SL, Hajishengallis G. A new inflammatory cytokine on the block: re-thinking periodontal disease and the Th1/Th2 paradigm in the context of Th17 cells and IL-17. J Dent Res. 2008;87:817–828. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garant PR. Plaque-neutrophil interaction in monoinfected rats as visualized by transmission electron microscopy. J Periodontol. 1976;47:132–138. doi: 10.1902/jop.1976.47.3.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garlet GP, Avila-Campos MJ, Milanezi CM, Ferreira BR, Silva JS. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans-induced periodontal disease in mice: patterns of cytokine, chemokine, and chemokine receptor expression and leukocyte migration. Microbes Infect. 2005;7:738–747. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garlet GP, Cardoso CR, Silva TA, et al. Cytokine pattern determines the progression of experimental periodontal disease induced by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans through the modulation of MMPs, RANKL, and their physiological inhibitors. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2006;21:12–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2005.00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garlet GP, Martins W, Jr, Ferreira BR, Milanezi CM, Silva JS. Patterns of chemokines and chemokine receptors expression in different forms of human periodontal disease. J Periodontal Res. 2003;38:210–217. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2003.02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glowacki AJ, Yoshizawa S, Jhunjhunwala S, et al. Prevention of inflammation-mediated bone loss in murine and canine periodontal disease via recruitment of regulatory lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:18525–18530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302829110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz B, Kataria N, Blazar BR, Miller JS, Verneris MR. Natural killer-cell differentiation by myeloid progenitors. Blood. 2011;117:3548–3558. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-281394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guentsch A, Puklo M, Preshaw PM, et al. Neutrophils in chronic and aggressive periodontitis in interaction with Porphyromonas gingivalis and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. J Periodontal Res. 2009;44:368–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2008.01113.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha J, Lee Y, Kim HH. CXCL2 mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced osteoclastogenesis in RANKL-primed precursors. Cytokine. 2011;55:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X, Amar S. Identification of genes differentially expressed in cultured human periodontal ligament fibroblasts vs. human gingival fibroblasts by DNA microarray analysis. J Dent Res. 2002;81:399–405. doi: 10.1177/154405910208100609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraszthy VI, Hariharan G, Tinoco EM, et al. Evidence for the role of highly leukotoxic Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in the pathogenesis of localized juvenile and other forms of early-onset periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2000;71:912–922. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.6.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey W, Wilson M, Meghji S. In vitro inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-induced bone resorption by polymyxin B. Br J Exp Pathol. 1986;67:699–705. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haubek D, Johansson A. Pathogenicity of the highly leukotoxic JP2 clone of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and its geographic dissemination and role in aggressive periodontitis. J Oral Microbiol. 2014:6. doi: 10.3402/jom.v6.23980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm A, Kalfas S, Holm SE. Killing of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Haemophilus aphrophilus by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes in serum and saliva. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1993;8:134–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1993.tb00655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotokezaka H, Sakai E, Ohara N, et al. Molecular analysis of RANKL-independent cell fusion of osteoclast-like cells induced by TNF-alpha, lipopolysaccharide, or peptidoglycan. J Cell Biochem. 2007;101:122–134. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im J, Baik JE, Kim KW, et al. Enterococcus faecalis lipoteichoic acid suppresses Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans lipopolysaccharide-induced IL-8 expression in human periodontal ligament cells. Int Immunol. 2015 doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxv016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara Y, Zhang JB, Quinn SM, et al. Regulation of immunoglobulin G2 production by prostaglandin E(2) and platelet-activating factor. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1563–1568. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1563-1568.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimi Y, Miyaura C, Jin CH, et al. IL-6 is produced by osteoblasts and induces bone resorption. J Immunol. 1990;145:3297–3303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izano EA, Sadovskaya I, Wang H, et al. Poly-N-acetylglucosamine mediates biofilm formation and detergent resistance in Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. Microb Pathog. 2008;44:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izawa A, Ishihara Y, Mizutani H, et al. Inflammatory bone loss in experimental periodontitis induced by Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans in interleukin-1 receptor antagonist knockout mice. Infect Immun. 2014;82:1904–1913. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01618-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson A, Sandstrom G, Claesson R, Hanstrom L, Kalfas S. Anaerobic neutrophil-dependent killing of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in relation to the bacterial leukotoxicity. Eur J Oral Sci. 2000;108:136–146. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2000.00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachlany SC, Fine DH, Figurski DH. Secretion of RTX leukotoxin by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6094–6100. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.11.6094-6100.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagermeier AS, London J. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans strains Y4 and N27 adhere to hydroxyapatite by distinctive mechanisms. Infect Immun. 1985;47:654–658. doi: 10.1128/iai.47.3.654-658.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J, de Brito Bezerra B, Pacios S, et al. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans infection enhances apoptosis in vivo through a caspase-3-dependent mechanism in experimental periodontitis. Infect Immun. 2012;80:2247–2256. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06371-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur M, Kachlany SC. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin (LtxA; Leukothera) induces cofilin dephosphorylation and actin depolymerization during killing of malignant monocytes. Microbiology. 2014;160:2443–2452. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.082347-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto D, Ando ES, Longo PL, Nunes AC, Wikstrom M, Mayer MP. Genetic diversity and toxic activity of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans isolates. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2009;24:493–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2009.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelk P, Abd H, Claesson R, Sandstrom G, Sjostedt A, Johansson A. Cellular and molecular response of human macrophages exposed to Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin. Cell Death Dis. 2011;2:e126. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelk P, Johansson A, Claesson R, Hanstrom L, Kalfas S. Caspase 1 involvement in human monocyte lysis induced by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin. Infect Immun. 2003;71:4448–4455. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.8.4448-4455.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi T, Hahn CL, Tanaka S, Barbour SE, Schenkein HA, Tew JG. Dendritic cells stimulated with Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans elicit rapid gamma interferon responses by natural killer cells. Infect Immun. 2004;72:5089–5096. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5089-5096.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Sato K, Asagiri M, Morita I, Soma K, Takayanagi H. Contribution of nuclear factor of activated T cells c1 to the transcriptional control of immunoreceptor osteoclast-associated receptor but not triggering receptor expressed by myeloid cells-2 during osteoclastogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32905–32913. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505820200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinane DF, Johnston FA, Evans CW. Depressed helper-to-suppressor T-cell ratios in early-onset forms of periodontal disease. J Periodontal Res. 1989;24:161–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1989.tb02000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi H, Nagasawa T, Aramaki M, Mahanonda R, Ishikawa I. Individual diversities in interferon gamma production by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells stimulated with periodontopathic bacteria. J Periodontal Res. 2000;35:319–328. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2000.035006319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]