Abstract

Introduction

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) is an important driver for resistance- and virulence factor accumulation in pathogenic bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus.

Methods

Here, we have investigated the downstream region of the bacterial chromosomal attachment site (attB) for the staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) element of a commensal mecC-positive Staphylococcus stepanovicii strain (IMT28705; ODD4) with respect to genetic composition and indications of HGT. S. stepanovicii IMT28705 was isolated from a fecal sample of a trapped wild bank vole (Myodes glareolus) during a screening study (National Network on “Rodent-Borne Pathogens”) in Germany. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) of IMT28705 together with the mecC-negative type strain CM7717 was conducted in order to comparatively investigate the genomic region downstream of attB (GenBank accession no. KR732654 and KR732653).

Results

The bank vole isolate (IMT28705) harbors a mecC gene which shares 99.2% nucleotide (and 98.5% amino acid) sequence identity with mecC of MRSA_LGA251. In addition, the mecC-encoding region harbors the typical blaZ-mecC-mecR1-mecI structure, corresponding with the class E mec complex. While the sequences downstream of attB in both S. stepanovicii isolates (IMT28705 and CM7717) are partitioned by 15 bp direct repeats, further comparison revealed a remarkable low concordance of gene content, indicating a chromosomal “hot spot” for foreign DNA integration and exchange.

Conclusion

Our data highlight the necessity for further research on transmission routes of resistance encoding factors from the environmental and wildlife resistome.

Introduction

Since the late 1970’s, methicillin resistance in coagulase-positive staphylococci (CPS) emerged as a major threat to both human and veterinary medicine [1]. Methicillin resistance is conferred by an additional penicillin binding protein (PBP2a), which substitutes the transpeptidase function of the native PBP2 during the crucial process of bacterial cell wall building in the presence of beta-lactam antibiotics [2]. The gene encoding PBP2a in staphylococci is part of a mec complex, consisting of a methicillin resistance encoding mec homologue (mecA or mecC), which is usually accompanied by intact or truncated versions of the regulatory genes mecI (repressor) and mecR1 (sensor inducer) [3,4]. A further regulatory component, mecR2 (antirepressor) influencing methicillin resistance levels, was recently described [5]. So far, three different allotypes were described for mecA and mecC, respectively [6].

The mec complex can be part of a larger, potential mobile element called staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec). These SCCmec elements also contain site-specific recombinase genes (ccrAB or ccrC) and flanking “junkyard” or “joining” (“J”) regions (J1–J3) [7,8]. In Staphylococcus aureus, the SCCmec insertion occurs at the bacterial chromosomal attachment site (attBSCC), represented by the terminal nucleotides of the 3’ end of an rRNA methyltransferase (formerly: orfX), leaving the gene functionally intact [9]. Usually, SCCmec elements are flanked by characteristic sequences of 15 bp (“direct repeats”; DR) that are recognized by the recombinases catalyzing the processes of chromosomal excision and integration [10,11]. Spontaneous excision of SCCmec leaves only one DR in the chromosome [12,13]. A review by the International Working Group on the Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome elements (IWG-SCC) published in 2009 provides an overview on the eleven distinct SCCmec elements, several other SCC’s as well as atypical SCCmec elements which have been described so far [14]. In addition, the IWG-SCC hosts a data base on current SCCmec elements (http://www.sccmec.org/).

In 2011, a mecA homologue denominated as mecC located on an SCCmec type XI element was described in methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolates from both human and bovine origin, and later also from a range of other animal species, including companion animals and wild small mammals [15–19]. This mecC gene shows 69% nucleotide- and 63% amino acid sequence identity to mecA resp. PBP2a of S. aureus N315. Similar to mecA, it was the suspect that mecC also originated from coagulase-negative staphylococci (CNS). The recent findings of two further mecC allotypes in CNS denominated as mecC1 (S. xylosus, cattle) and mecC2 (S. saprophyticus, common shrew) may support this hypothesis [20,21]. In addition, a further study identified the mecC gene in a CNS isolate from an Eurasian lynx which is most probably Staphylococcus stepanovicii [22], a species that is considered as a persistent member of physiological microflora of the skin of wild small mammals [23]. Here we report the characterization of the methicillin resistance encoding region in a S. stepanovicii isolate (IMT28705; ODD4) harboring a mecC gene. According to the definition of the IWG-SCC [14], the region was denominated as ψSCCmecIMT28705. The mecC-negative S. stepanovicii type strain CCM7717[24] was included to compare the genomic arrangement of the two regions downstream of attBSCC.

Material and Methods

The Staphylococcus stepanovicii strain IMT28705 (ODD4) was isolated in August 2011 from a fecal sample of a live-trapped male bank vole (Myodes glareolus) of 26 g weight, collected during October 2011 at forest monitoring site #1 in Jeeser, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, North-East Germany [25], as part of a screening study focusing on pathogens from wild rodents in Germany (Network “Rodent-Borne Pathogens” [26]. The rodent trapping was approved by the competent authority of the Federal State of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Germany, on the basis of national and European legislation (LALLF-M-V/TSD/7221.3-030/09). Rectal swabs were enriched by use of an enrichment broth to enhance staphylococcal growth and to prevent Gram-negative overgrowth [27]. A positive PCR-result for the mecC gene using the primers published by Cuny et al. [15] was the initial reason for sequencing the whole genome of the mecC-positive strain (IMT28705) on a HiSeq (Illumina, USA). To gain deeper insights into the genomic region downstream of attBSCC within this staphylococcal species, we included the mecC-negative S. stepanovicii type strain (CCM7717) [24]. The reads were assembled using CLC Genomics Workbench 7.5 (CLC bio, Denmark) and open reading frames (ORFs) were predicted using Prodigal: Prokaryotic Dynamic Programming Genefinding Algorithm [28]. Annotation of ORFs and prediction of (protein) coding sequences (CDS) was performed by The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology [29]. Putative CDS function and conserved domains were predicted with blastn and blastx using the NCBI database (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). The presence of sequence homology to proteins encoded by diverse families of transposable elements in the genomes was performed by PSI-Blast within the TransposonPSI tool (http://transposonpsi.sourceforge.net/). For genomic comparative analyses Geneious 7.1.5 was employed. Putative integration site sequences were identified as DR using the following screening sequence: GAA[AG][CG][TA]TATCATAA[GA].

Both S. stepanovicii isolates were subjected to disc diffusion test using cefoxitin (30 μg) according to CLSI standards [30,31]. Automated determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) for both S. stepanovicii isolates was performed using the bioMerieux VITEK®2 system according to the manufacturer’s instructions, including benzyl-penicillin, oxacillin, gentamicin, enrofloxacin, marbofloxacin, erythromycin, clindamycin, tetracycline, chloramphenicol and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute.

Results and Discussion

Species identity of IMT28705 was determined by 16S rDNA sequence analysis (GenBank accession no. KR732655), revealing a homology of 99.9% with the type strain CCM7717. Here we report on the entire nucleotide sequence region between the rRNA-methyltransferase (orfX)-like gene and the tRNA dihydrouridine synthase B (orfY)-like gene in a mecC-positive strain (IMT28705, GenBank accession no. KR732654) and the mecC-negative reference strain (CCM7717, GenBank accession no. KR732653). Genome sequencing revealed that strain IMT28705 harbors a mecC gene which shares 99.2% nucleotide (and 98.5% amino acid) sequence identity with mecC of MRSA_LGA251. At the chromosomal insertion site of SCCmec, five terminal amino acids were encoded by 15 bp, followed by a stop codon sequence (TGA). Insertion of SCCmec alters this site to attR1 or DR1. In IMT28705, the attR1 integration site at the end of the rRNA-methyltransferase (orfX)-like gene is indicated by GAAAGTTATCATAAATGA (DR1) encoding the terminal amino acids ESYHK. Corresponding DRs are located 8,884 bp (DR2: GAAGCATATCATAAATGA, encoding EAYHK) as well as 13,757 bp (DR3: GAAAGTTATCATAAGTGA, encoding again ESYHK) downstream of DR1 (Fig 1). These DRs are analogues sequences to those reported for other SCCmec elements, including those reported for MRSA [11,32], indicating a broad and general exchangeability of genomic regions flanked by these universal distributed DR sequences downstream of attBSCC, at least among staphylococci. Furthermore, these DR sequences were also detected as partitioning sequences in prototype strain CCM7717, starting with the terminal EAYHK-encoded motif within the rRNA-methyltransferase (orfX)-like gene (Fig 2).

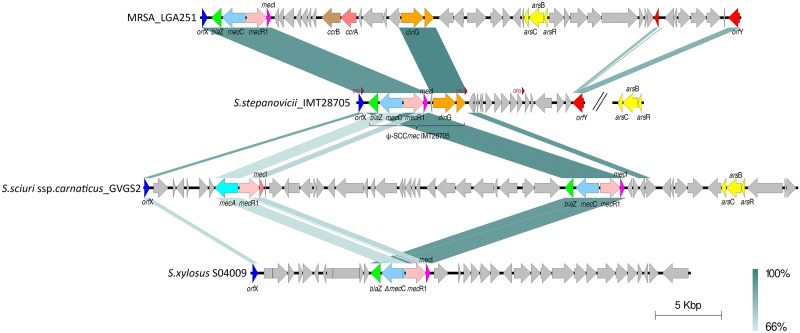

Fig 1. Comparison of the genetic structure of the region downstream of orfX-like gene (rRNA-methyltransferase) for S. stepanovicii strain IMT28705 with MRSA_LGA251, S. sciuri ssp. carnaticus_GVGS2, and S. xylosus_SO4009.

Direct repeats (DR) of IMT28705 are indicated by red arrowheads. Conserved DNA regions are shown by dark green color; more dissimilar sequences are indicated with light green. Arrows indicate ORFs and their orientation on the genome. Selected ORFs were colored to illustrate orthologs between the genomes. Nucleotide sequence similarities for IMT28705 are given in Table 1.

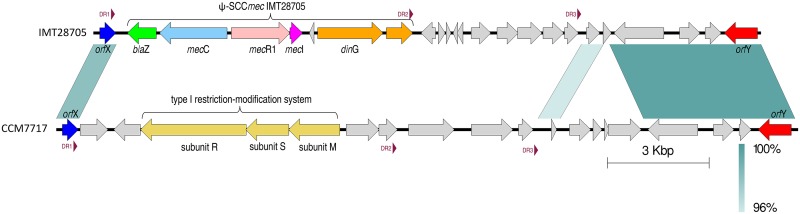

Fig 2. Genomic comparison of the DNA sequences between orfX (rRNA-methyltransferase-like gene) and the orfY-like gene of the S. stepanovicii strains IMT28705 (mecC-positive) with CCM7717 (mecC-negative).

Direct repeats (DR) are indicated by red arrowheads, conserved DNA regions are shown by dark green color; more dissimilar sequences are indicated with light green. A remarkable divergence in the genomic structure downstream of the bacterial chromosomal attachment site (attB) is obvious, indicating a genomic “hot spot” for integration and excision of foreign DNA in S. stepanovicii. In addition, a blastn search (12/2014) revealed an absolutely low degree of nucleotide sequence similarities for this region of CCM7717 (S1 Table).

In IMT28705, the mecC-encoding region follows directly the attR1 (DR1) integration site with a very short (25 bp) J-region. Immediately downstream follows the typical blaZ-mecC-mecR1-mecI structure of 5,163 bp corresponding to the class E mec complex described for MRSA_LG251, S. xylosus (S04009) and S. sciuri ssp. carnaticus [16,20,33] (Fig 1). A similar structure (including mecB instead of different mecC allotypes) was reported for Macrococcus caseolyticus (a Gram-positive species that was formerly classified as Staphylococcus caseolyticus), either as part of a transposon located on plasmids or within an SCCmec element [34]. A comparative analysis of these mec-encoding regions including M. caseolyticus is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Comparison of IMT28705 class E mec complex with other mec E complexes.

| Nucleotide sequence similarity | MRSA_LGA251 | S. stepanovicii_3orsfiwi | S. xylosus_S04009 | S. sciruri carnaticus_GVGS2 | M. caseolyticus_JCSC7096 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF | Description / presumptive function | C | NI | C | NI | C | NI | C | NI | C | NI | |

| blaZ | Beta-lactamase | 100% | 97% | 87% | 99% | 98% | 91% | 100% | 98% | 98% | 61% | |

| mecC | Penicillin-binding protein PBP2a, transpeptidase | 100% | 99% | 88% | 100% | 99%* | 93% | 100% | 96% | 100% | 63% | |

| ψSCCmecIMT28705 | mecR | Methicillin resistance regulatory sensor-transducer MecR1 | 100% | 89% | n. a. | n. a. | 100% | 97% | 100% | 90% | 99% | 58% |

| mecI | Methicillin resistance repressor MecI | 95% | 91% | n. a. | n. a. | 100% | 99% | 98% | 91% | 100% | 64% | |

| CDS_1 | hypothetical protein | 69% | 91% | n. a. | n. a. | 33% | 94% | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | |

| dinG | DinG family (ATP-dependent helicase YoaA) | 100% | 96% | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | |

| CDS_2 | hypothetical protein | 100% | 99% | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | n. a. | |

Abbreviations: ORF: open reading frame; C: coverage; N: nucleotide identity, *pseudogene, CDS: coding sequence; Nucleotide sequence identities (%) of homologues genes of different mec E complexes (GenBank entries) in comparison with ψSCCmecIMT28705. Notably, nucleotide sequence identities for the regulatory genes mecR1 and mecI are 97% and 99% for S. xylosus_S04009 and thus higher than those for MRSA_LGA2951 (89% / 91%) and S. sciruri carnaticus_GVGS2 (90%/91%).

It has been assumed that the initial formation of the mec complex is a result of the integration of a (putative chromosomal) mec allotype in an intact beta-lactamase operon blaZ-(mecA)-blaR1-blaI followed by the loss of the native beta-lactamase-encoding blaZ over time [34,35]. Furthermore, the blaZ regulator genes blaR1 and blaI influence the expression levels regulated by mecR1 and mecI (“cross-talk”) of mecA in methicillin resistant staphylococci, too [5]. From an evolutionary perspective, the mec E with its “ancestral” blaZ is an interesting phenomenon: This structure is either more conserved than comparable progenitor forms of other mec complexes harboring mecA allotypes and/or benefits from the potential antimicrobial activity of blaZ. The penicillin resistance noticed for an oxacillin susceptible S. xylosus strain harboring a truncated mecC1 within its mec E complex might be an example for the latter case [20]. Contrariwise, mecC MRSA strains did not express elevated beta-lactamase activity levels so far [6].

For the S. stepanovicii strains reported here, the disc diffusion test showed an inhibition zone diameter of 22 mm for cefoxitin for IMT28705 (= methicillin resistant phenotype), the mecC-negative strain (CCM7717) exhibited 29 mm (= susceptible phenotype) according to the utilized interpretation criteria [30]. As presented in Table 2, the oxacillin MICs for both the mecC-negative S. stepanovicii strain and the mecC-positive strain IMT28705 were ≥4 mg/L. However, increased oxacillin MICs for CNS lacking mecA or mecC as well as unusual beta-lactamase (hyper-) production were reported before, especially for isolates from bovine milk samples [36,37]. Moreover, Skov et al. reported in 2014 that cefoxitin is more reliable than oxacillin for mecC-associated methicillin resistance in S. aureus [38].

Table 2. Results of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) testing of S. stepanovicii isolates using VITEK®2.

| Antimicrobial substance | IMT28705 | CM7717 |

|---|---|---|

| benzyl-penicillin | ≥ 0.5 | 0.12 |

| oxacillin | ≥ 4 | ≥ 4 |

| gentamicin | ≤ 0.5 | ≤ 0.5 |

| enrofloxacin | ≤ 0.5 | ≤ 0.5 |

| marbofloxacin | 1 | ≤ 0,5 |

| erythromycin | ≤ 0.25 | ≤ 0.25 |

| clindamycin | ≤ 0.25 | ≤ 0.25 |

| tetracycline | ≤ 1 | ≤ 1 |

| chloramphenicol | 8 | 8 |

| trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | ≤ 10 | ≤ 10 |

| Cefoxitin-Screen | + | - |

| Inducible clindamycin resistance | - | - |

Bold = resistant according to Vet01-S2 [30].

No major differences were seen in MICs for the other antibiotics tested (Table 2).

In IMT28705, the region between the orfX and orfY-like genes does not harbor a known transposable element, neither as a full ORF nor as a truncated remnant (Table 3 and Fig 1). In addition, no ccr homologues were identified. Thus, the mecC region in IMT28705 seems to lack factors associated with potential mobility of an SCCmec element. We therefore propose to denominate the region between DR1 and DR2 (8,884 bp) lacking ccr genes as ψSCCmecIMT28705 (Fig 1), according to the definition provided by the IWG-SCC [14].

Table 3. Nucleotide sequence similarities downstream of rlmH (formerly orfX) to orfY-like genes (gb KR732654) of the bank vole-derived mecC-positive S. stepanovicii strain IMT28705 and other bacterial strains taken from GenBank entries.

| ORF | Description / presumptive function | from* | to* | bp | C | NI | Accession no. | Species (gene location), strain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LSU m3Psi1915 methyltransferase RlmH (orfX-like) | 219 | 698 | 480 | 100% | 87% | HG515014.1 | S. sciuri ssp. carnaticus, GVGS2 |

| ψSCCmecIMT28705 | 1,039 | 9,453 | 8,884 | |||||

| 2 | Beta-lactamase (EC 3.5.2.6) | 1,039 | 1,890 | 852 | 100% | 98% | HG515014.1 | S. sciuri ssp. carnaticus, GVGS2 |

| 3 | Penicillin-binding protein PBP2a, transpeptidase | 1,984 | 3,978 | 1,995 | 100% | 99% | FR821779.1 | S. aureus (SCCmec), MRSA_LGA251 |

| 4 | Methicillin resistance regulatory sensor-transducer MecR1 | 4,100 | 5,833 | 1,734 | 100% | 97% | HE993884.1 | S. xylosus (SCCmec), HE993884 |

| 5 | Methicillin resistance repressor MecI | 5,830 | 6,207 | 378 | 100% | 99% | HE993884.1 | S. xylosus (SCCmec), HE993884 |

| 6 | hypothetical protein 1 | 6,403 | 6,543 | 141 | 69% | 91% | FR821779.1 | S. aureus (SCCmec), MRSA_LGA251 |

| 7 | DinG family ATP-dependent helicase YoaA | 6,649 | 8,580 | 1,932 | 100% | 96% | FR821779.1 | S. aureus (SCCmec), MRSA_LGA251 |

| 8 | putative membrane protein | 8,674 | 9,453 | 780 | 100% | 99% | FR821779.1 | S. aureus (SCCmec),MRSA_ LGA251 |

| Region between DR2 and DR3 | 9,580 | 14,455 | 4,875 | |||||

| 9 | PhnB, putative ribosomal methyltransferase | 9,701 | 10,129 | 429 | 100% | 93% | KF527883.1 | S. aureus, (SCCmec), NTUH-4729 |

| 10 | hypothetical protein (transcriptional regulator DeoR family) | 10,208 | 10,411 | 204 | 98% | 93% | HG515014.1 | S. sciuri ssp. carnaticus, (SCCmec), GVGS2 |

| 11 | hypothetical protein (transcriptional regulator DeoR family) | 10,439 | 10,582 | 144 | 97% | 100% | |HG515014.1 | S. sciuri ssp. carnaticus, (SCCmec), GVGS3 |

| 12 | hypothetical protein | 10,643 | 10,783 | 141 | no similarities | |||

| 13 | hypothetical protein | 10,764 | 10,940 | 177 | no similarities | |||

| 14 | hypothetical protein | 11,181 | 11,756 | 576 | 88% | 72% | CP002439.1 | S. pseudintermedius, (SCCmec), HKU10-03 |

| 15 | conserved hypothetical protein | 11,939 | 12,565 | 627 | 100% | 89% | AB498756.1 | M. caseolyticus, (mecB region), JCSC7096 |

| 16 | putative glucose-1-phosphate adenylyltransferase GlgD | 12,543 | 13,265 | 723 | 100% | 96% | AB498757.1 | M. caseolyticus, (mecB region), JCSC7528 |

| 17 | putative serine/threonine-specific protein phosphatase 21 | 13,296 | 13,904 | 609 | no similarities | |||

| 18 | hypothetical protein | 13,930 | 14,343 | 414 | 100% | 87% | AB261975.1 | S. aureus (J1 region, SCCmec), RN7170 |

| Region between DR3 and orfY-like gene | 14,456 | 18,645 | 4,189 | |||||

| 19 | hypothetical protein | 14,577 | 14,975 | 399 | no similarities | |||

| 20 | hypothetical protein | 15,071 | 15,316 | 246 | no similarities | |||

| 21 | hypothetical protein | 15,391 | 16,866 | 1,476 | 46% | 66% | HE980450.1 | S. aureus,(SCCmec), M06/0171 |

| 22 | hypothetical protein | 17,323 | 17,928 | 606 | 92% | 69% | CP006044.1 | S. aureus (SCCmec), CA-347 |

| 23 | putative acetyltransferase (GNAT) family protein | 18,083 | 18,556 | 474 | 85% | 76% | CP007447.1 | S. aureus (SCCmec), XN108 |

| 24 | probable tRNA-dihydrouridine synthase (orfY-like) | 18,645 | 19,625 | 981 | 98% | 85% | FR821777.2 | S. aureus (SCCmec), MSHR1132 |

Abbreviations: ORF: open reading frame, bp: base pair, C: Coverage; NI: nucleotide similarity; DR: direct repeat of 15 bp

1 predicted by use of blastx;

* nucleotide position in ψSCCmecIMT28705 (GenBank accession no. KR732654)

Downstream of the class E mec complex, the damage inducible gene G (dinG) of the S. stepanovicii strain IMT28705 shares 96% nucleotide sequence identity with the corresponding homologue of MRSA_LGA251 (Fig 1, Table 3). The dinG encoded protein represents a fusion between a helicase and a nuclease often working together in the processes involved in DNA repair and recombination [39], a function providing a potential benefit in regions associated with recombination events. The last ORF (780 bp) comprised by ψSCCmecIMT28705 shows 96% nucleotide sequence identity to a hypothetical membrane protein (SARLGA251_00430) of MRSA_LGA251, lacking putative conserved regions (Table 3). Insertion sequences (IS) and transposons (Tn), frequently associated with SCCmec elements such as IS431, IS1272 or Tn554 were not identified. A second region comprising 4,876 bp in IMT28705 is flanked by DR2 and DR3 and starts with an ORF (429 bp) encoding a putative PhnB-like protein, which was reported for SCCmecV elements of Indian origin only recently, including structural folds similar to bleomycin resistance protein [40]. Next, two putative transcriptional regulators (DeoR family) also present in S. sciuri ssp. carnaticus_GVGS2, (Table 3) as well as in many other staphylococci, are part of the region downstream of orfX (data not shown). Two further ORFs providing no significant similarities in the NCBI nucleotide / protein databases were followed by a coding region for a hypothetical protein also present in the SCCmec element of S. pseudintermedius strain HKU-1003. These are adjacent to sequences encoding a conserved hypothetical protein and a putative glucose-1-phosphate adenylyltransferase, both reported for the mecB ecoding region in M. caseolyticus. The next ORFs encode a putative serine/threonine-specific protein phosphatase (predicted by use of blastx) and a further hypothetical protein also described for the J1 region in MRSA strain RN71170 (Table 3).

The third region flanked by DR3 and the orfY-like gene comprises 4,171 bp and at least six distinct ORFs. Notably, a search on the EMBL database for sequences of this region (between bp positions 14,577 and 16,866) showed only a few hits and a very low nucleotide sequence similarity (date: 12/2014) by use of blastn (Table 3). An arsenic resistance operon described for the SCCmec region of MRSA_LGA251 is located 35 kb downstream of the orfY-like gene in IMT28705. A similar operon is reported for S. xylosus_S04009 (Fig 1).

The mecC-negative reference strain (CCM7717) showed DR1 sequence GAAGCATATCATAAATAA at the 3’ end of the rRNA-methyltransferase (orfX-like) gene, followed by a region of 9,527 bp ending with DR2 (GAAAGTTATCATAAGTAA) and a further part consisting of 4,057 bp ending with DR3 (GAAAGTTATCATAAGTGA). As displayed in Fig 2, the gene content of this region differs remarkably from that of IMT28705. However, a type I restriction modification system (5,885 bp) consisting of hsdR, hsdS and hsdM is present downstream of orfX in CCM7717, showing significant nucleotide sequence similarities (coverage: 82%; identity 89%) with the homologous region in MRSA_LGA251 (S1 Table). This particular restriction modification system was described for SCCmecV and has been discussed as a stabilizing factor for these elements [10,32]. A further blastn search of the entire region downstream of DR1 in CCM7717 revealed some sequence similarities to ORFs with predominantly unknown functions within other staphylococci (especially in different SCCmec elements), but for seven ORFs the entered sequence data provided no significant hits or similarities so far (01/2015, S1 Table).

In recent years, it has been assumed that the methicillin resistance conferring PBP2a encoded by allotypes of mecA and mecC originates from CNS including the S. sciuri group, Staphylococcus fleurettii and other CNS [13,41,42]. The identification of the origin of genes encoding methicillin resistance among CNS is important for understanding the evolution of pathogenic methicillin resistant CPS and may contribute to the development of more effective control measures [13].

Here we report about a class E mec complex and some associated ORFs with strong similarities to the strains MRSA_LGA251 and S. xylosus S04009. Furthermore, the mosaic structure of the region downstream of orfX in both S. stepanovicii strains (IMT28705 and CCM7717) is not associated with the presence/or absence of mecC and/or an SCCmec element. Taken together, the orfX-like region seems to be a putative integration site of foreign DNA in S. stepanovicii, representing a “melting pot”, like it has been described for S. aureus and other members of the Staphylococcus genus previously [43,44]. Furthermore, a recent study revealed that the limited distance between the region downstream of orfX (recently renamed as rlmH) and the origin of replication (oriC) in S. aureus (38 kb in the genomes of IMT28705 and CCM7717) is a strong predictor for a recombination hot spot [45].

However, the broad distribution of certain genes within this particular chromosomal location in different staphylococcal species raises the question if other routes of horizontal gene transfer beside interaction with serine recombinase family genes (ccr) might exist. For instance, recent studies showed the general transmissibility of SCCmec elements or parts of them by different bacteriophages [46,47].

Whether ψSCCmecIMT28705 represents an evolutionary precursor of SCCmecXI or not is not clear yet, but is at least a possible option, which has been discussed for mecA-harboring CNS and MRSA before [34,35,44]. Further genomic analysis of CNS originating from wildlife (including small mammal rodents) is clearly needed to unravel the primordial origin of mecC (and other mec allotypes) and to answer the question where the mec complex gets its mobility from. In conclusion, our data highlight the role of the environmental and wildlife resistome as an important source of antibiotic resistance in opportunistic and zoonotic bacterial species such as S. aureus and the putative transferability of further factors and elements flanked by DR downstream of attB, an important “melting pot” for genetic rearrangements.

Transparency Declarations

Dr. Stamm is an employee of IDEXX Vet Med Labor GmbH (Ludwigsburg). Whilst this author is a company employee, this does not alter the adherence to all the PLoS ONE policies on sharing data and materials for this manuscript. All other authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Supporting Information

Abbreviations: ORF: open reading frame, bp: base pair, C: Coverage; NI: nucleotide sequence identity; DR: direct repeat of 15 bp. 1 predicted by use of blastx.

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

The collection and providing of the bank vole faeces sample by Sabrina Schmidt, Ulrike M. Rosenfeld and Nastasja Kratzmann is kindly acknowledged.

Data Availability

Sequence data of the genomic region downstream of bacterial chromosomal attachment site (attB) are available from GenBank accession no. KR732654 (IMT28705) and KR732653 (CM7717).

Funding Statement

The funder provided support in the form of salaries for authors [IS], but did not have any additional role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The study was not financially supported by IDEXX. The specific roles of these authors are articulated in the ‘author contributions’ section. This work was supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) through the National Research Platform for Zoonoses (MedVet- Staph, grant no. 01KI1301F to BW) and Network “Rodent-borne Pathogens”; (NaÜPa-net; grant nos. 01KI1018 and 01KI1303 to RGU). TS was financed through BMBF grant FBI-Zoo (grant no. 01KI1012A). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Wieler LH, Ewers C, Guenther S, Walther B, Lübke-Becker A. Methicillin-resistant staphylococci (MRS) and extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae in companion animals: nosocomial infections as one reason for the rising prevalence of these potential zoonotic pathogens in clinical samples. Int J Med Microbiol. 2011;301(8):635–41. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2011.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinho MG, de Lencastre H, Tomasz A. An acquired and a native penicillin-binding protein cooperate in building the cell wall of drug-resistant staphylococci. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98. 2001;98(19):10886–91. 10.1073/pnas.191260798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ito T, Hiramatsu K, Tomasz A, de Lencastre H, Perreten V, Holden MT, et al. Guidelines for reporting novel mecA gene homologues. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(10):4997–9. 10.1128/AAC.01199-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shore AC, Coleman DC. Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec: recent advances and new insights. Int J Med Microbiol. 2013;303(6–7):350–9. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arede P, Milheirico C, de Lencastre H, Oliveira DC. The anti-repressor MecR2 promotes the proteolysis of the mecA repressor and enables optimal expression of beta-lactam resistance in MRSA. PLoS pathogens. 2012;8(7):e1002816 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker K, Ballhausen B, Köck R, Kriegeskorte A. Methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus isolates: the "mec alphabet" with specific consideration of mecC, a mec homolog associated with zoonotic S. aureus lineages. Int J Med Microbiol. 2014;304(7):794–804. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2014.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deurenberg RH, Vink C, Oudhuis GJ, Mooij JE, Driessen C, Coppens G, et al. Different clonal complexes of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus are disseminated in the Euregio Meuse-Rhine region. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49(10):4263–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ito T, Okuma K, Ma XX, Yuzawa H, Hiramatsu K. Insights on antibiotic resistance of Staphylococcus aureus from its whole genome: genomic island SCC. Drug Resist Updat. 2003;6(1):41–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boundy S, Safo MK, Wang L, Musayev FN, O'Farrell HC, Rife JP, et al. Characterization of the Staphylococcus aureus rRNA methyltransferase encoded by orfX, the gene containing the Staphylococcal Chromosome Cassette mec (SCCmec) insertion site. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(1):132–40. 10.1074/jbc.M112.385138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanssen AM, Ericson Sollid JU. SCCmec in staphylococci: genes on the move. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2006;46(1):8–20. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2005.00009.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L, Safo M, Archer GL. Characterization of DNA sequences required for the CcrAB-mediated integration of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec, a Staphylococcus aureus genomic island. J Bacteriol. 2012;194(2):486–98. 10.1128/JB.05047-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katayama Y, Ito T, Hiramatsu K. Genetic organization of the chromosome region surrounding mecA in clinical staphylococcal strains: role of IS431-mediated mecI deletion in expression of resistance in mecA-carrying, low-level methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus haemolyticus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45(7):1955–63. 10.1128/AAC.45.7.1955-1963.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsubakishita S, Kuwahara-Arai K, Sasaki T, Hiramatsu K. Origin and molecular evolution of the determinant of methicillin resistance in staphylococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(10):4352–9. 10.1128/AAC.00356-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.International Working Group on the Classification of Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome (SCC) Elements” (IWG-SCC). Classification of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec): guidelines for reporting novel SCCmec elements. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53(12):4961–7. 10.1128/AAC.00579-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuny C, Layer F, Strommenger B, Witte W. Rare occurrence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus CC130 with a novel mecA homologue in humans in Germany. PloS one. 2011;6(9):e24360 10.1371/journal.pone.0024360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia-Alvarez L, Holden MT, Lindsay H, Webb CR, Brown DF, Curran MD, et al. Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with a novel mecA homologue in human and bovine populations in the UK and Denmark: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(8):595–603. S1473-3099(11)70126-8 [pii] 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70126-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomez P, Gonzalez-Barrio D, Benito D, Garcia JT, Vinuela J, Zarazaga M, et al. Detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) carrying the mecC gene in wild small mammals in Spain. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(8):2061–4. 10.1093/jac/dku100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paterson GK, Larsen AR, Robb A, Edwards GE, Pennycott TW, Foster G, et al. The newly described mecA homologue, mecALGA251, is present in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from a diverse range of host species. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(12):2809–13. 10.1093/jac/dks329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walther B, Wieler LH, Vincze S, Antao EM, Brandenburg A, Stamm I, et al. MRSA variant in companion animals. Emerg Infec Dis. 2012;18(12):2017–20. 10.3201/eid1812.120238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrison EM, Paterson GK, Holden MT, Morgan FJ, Larsen AR, Petersen A, et al. A Staphylococcus xylosus isolate with a new mecC allotype. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(3):1524–8. 10.1128/AAC.01882-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malyszko I, Schwarz S, Hauschild T. Detection of a new mecC allotype, mecC2, in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus saprophyticus. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(7):2003–5. 10.1093/jac/dku043 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loncaric I, Kubber-Heiss A, Posautz A, Stalder GL, Hoffmann D, Rosengarten R, et al. Characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus spp. carrying the mecC gene, isolated from wildlife. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(10):2222–5. 10.1093/jac/dkt186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hauschild T, Slizewski P, Masiewicz P. Species distribution of staphylococci from small wild mammals. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2010;33(8):457–60. 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hauschild T, Stepanovic S, Zakrzewska-Czerwinska J. Staphylococcus stepanovicii sp. nov., a novel novobiocin-resistant oxidase-positive staphylococcal species isolated from wild small mammals. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2010;33(4):183–7. 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacob J, Ulrich RG, Freise J, Schmolz E (2014) Monitoring populations of rodent reservoirs of zoonotic diseases. Projects, aims and results. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 57: 511–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ulrich RG, Schmidt-Chanasit J, Schlegel M, Jacob J, Pelz HJ, Mertens M, et al. Network "Rodent-borne pathogens" in Germany: longitudinal studies on the geographical distribution and prevalence of hantavirus infections. Parasitol Res. 2008;103 Suppl 1:S121–9. 10.1007/s00436-008-1054-9 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanselman BA, Kruth SA, Rousseau J, Weese JS. Coagulase positive staphylococcal colonization of humans and their household pets. Can Vet J. 2009;50(9):954–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hyatt D, Chen GL, Locascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC bioinformatics. 2010;11:119 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Overbeek R, Olson R, Pusch GD, Olsen GJ, Davis JJ, Disz T, et al. The SEED and the Rapid Annotation of microbial genomes using Subsystems Technology (RAST). Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D206–14. 10.1093/nar/gkt1226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Vet01-S2 Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk and Dilution Susceptibility for Bacteria isolated from Animals Second International Supplement, Wayne, PA, USA: 2013;32/ 2. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance standards for antimicrobial disk and dilution susceptibility tests for bacteria isolated from animals; approved standard VET01-A4. 4th ed, Wayne, PA, USA. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ito T, Ma XX, Takeuchi F, Okuma K, Yuzawa H, Hiramatsu K. Novel type V staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec driven by a novel cassette chromosome recombinase, ccrC. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(7):2637–51. 10.1128/AAC.48.7.2637-2651.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harrison EM, Paterson GK, Holden MT, Ba X, Rolo J, Morgan FJ, et al. A novel hybrid SCCmec–mecC region in Staphylococcus sciuri. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(4):911–8. 10.1093/jac/dkt452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsubakishita S, Kuwahara-Arai K, Baba T, Hiramatsu K. Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec-like element in Macrococcus caseolyticus. 2010;54(4):1469–75. 10.1128/AAC.00575-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shore AC, Deasy EC, Slickers P, Brennan G, O'Connell B, Monecke S, et al. Detection of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec type XI carrying highly divergent mecA, mecI, mecR1, blaZ, and ccr genes in human clinical isolates of clonal complex 130 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(8):3765–73. 10.1128/AAC.00187-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fessler AT, Billerbeck C, Kadlec K, Schwarz S. Identification and characterization of methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci from bovine mastitis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65(8):1576–82. 10.1093/jac/dkq172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frey Y, Rodriguez JP, Thomann A, Schwendener S, Perreten V. Genetic characterization of antimicrobial resistance in coagulase-negative staphylococci from bovine mastitis milk. J Dairy Sci. 2013;96(4):2247–57. 10.3168/jds.2012-6091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skov R, Larsen AR, Kearns A, Holmes M, Teale C, Edwards G, et al. Phenotypic detection of mecC-MRSA: cefoxitin is more reliable than oxacillin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(1):133–5. 10.1093/jac/dkt341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McRobbie AM, Meyer B, Rouillon C, Petrovic-Stojanovska B, Liu H, White MF. Staphylococcus aureus DinG, a helicase that has evolved into a nuclease. Biochem J. 2012;442(1):77–84. 10.1042/BJ20111903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Balakuntla J, Prabhakara S, Arakere G. Novel rearrangements in the staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec type V elements of Indian ST772 and ST672 methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. PloS one. 2014;9(4):e94293 10.1371/journal.pone.0094293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Couto I, Wu SW, Tomasz A, de Lencastre H. Development of methicillin resistance in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus sciuri by transcriptional activation of the mecA homologue. J Bacteriol. 2003;185(2):645–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stepanovic S, Hauschild T, Dakic I, Al-Doori Z, Svabic-Vlahovic M, Ranin L, et al. Evaluation of phenotypic and molecular methods for detection of oxacillin resistance in members of the Staphylococcus sciuri group. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(3):934–7. 10.1128/JCM.44.3.934-937.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Noto MJ, Kreiswirth BN, Monk AB, Archer GL. Gene acquisition at the insertion site for SCCmec, the genomic island conferring methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2008;190(4):1276–83. 10.1128/JB.01128-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hiramatsu K, Ito T, Tsubakishita S, Sasaki T, Takeuchi F, Morimoto Y, et al. Genomic Basis for Methicillin Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Chemother. 2013;45(2):117–36. 10.3947/ic.2013.45.2.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Everitt RG, Didelot X, Batty EM, Miller RR, Knox K, Young BC, et al. Mobile elements drive recombination hotspots in the core genome of Staphylococcus aureus. Nat commun. 2014;5:3956 10.1038/ncomms4956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chlebowicz MA, Maslanova I, Kuntova L, Grundmann H, Pantucek R, Doskar J, et al. The Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome mec type V from Staphylococcus aureus ST398 is packaged into bacteriophage capsids. Int J Med Microbiol. 2014;304(5–6):764–74. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2014.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scharn CR, Tenover FC, Goering RV. Transduction of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec elements between strains of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(11):5233–8. 10.1128/AAC.01058-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Abbreviations: ORF: open reading frame, bp: base pair, C: Coverage; NI: nucleotide sequence identity; DR: direct repeat of 15 bp. 1 predicted by use of blastx.

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

Sequence data of the genomic region downstream of bacterial chromosomal attachment site (attB) are available from GenBank accession no. KR732654 (IMT28705) and KR732653 (CM7717).