Abstract

A microfluidic chip is proposed to separate microparticles using cross-flow filtration enhanced with hydrodynamic focusing. By exploiting a buffer flow from the side, the microparticles in the sample flow are pushed on one side of the microchannels, lining up to pass through the filters. Meanwhile a larger pressure gradient in the filters is obtained to enhance separation efficiency. Compared with the traditional cross-flow filtration, our proposed mechanism has the buffer flow to create a moving virtual boundary for the sample flow to actively push all the particles to reach the filters for separation. It further allows higher flow rates. The device only requires soft lithograph fabrication to create microchannels and a novel pressurized bonding technique to make high-aspect-ratio filtration structures. A mixture of polystyrene microparticles with 2.7 μm and 10.6 μm diameters are successfully separated. 96.2 ± 2.8% of the large particle are recovered with a purity of 97.9 ± 0.5%, while 97.5 ± 0.4% of the small particle are depleted with a purity of 99.2 ± 0.4% at a sample throughput of 10 μl/min. The experiment is also conducted to show the feasibility of this mechanism to separate biological cells with the sample solutions of spiked PC3 cells in whole blood. By virtue of its high separation efficiency, our device offers a label-free separation technique and potential integration with other components, thereby serving as a promising tool for continuous cell filtration and analysis applications.

INTRODUCTION

Particle and cell separation has been of great interest due to its diverse applications in industrial, biological, and medical fields.1–3 For example, due to the current interest in the investigation of bacteria living in association with humans, it was important to separate bacterial cells from human cells.4 Effective classification of blood cells can bring important information into the blood for diagnosis of diseases immune deficiency and genetic abnormalities.5 Isolation of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) assist doctors in monitoring patients' cancer progression.6,7 Various particle separation techniques have been developed for a fast, accurate, and label-free approach.8–12 As an ideal tool for manipulating microscale objects, microfluidics have demonstrated to separate particles and cells, including pinched flow fractionation (PFF),9–12 cross-flow filtration,13–17 microfluidic disk,18 laminar vortices,19,20 and centrifugation/inertial focusing.21–25 They possess the advantage of low-cost fabrication and massive parallelization, making high throughput sample processing possible for downstream analysis.

To separate cells, label-free separation techniques have been highly desirable as the use of biochemical markers can interfere with the cells; complicate the preparation procedures; and increase the associate cost. Among these label-free techniques, cross-flow filtration is one of the most commonly utilized techniques as it is simple, non-destructive, and easy for downstream process integration. This technique has been used to separate plasma, red blood cells (RBCs), leukocytes (WBCs), and rare cells from whole blood.13,14 Due to the flow direction being vertical to the filtration direction, cross-flow filtration can reduce aggregations of clogging of the particles and cells.26 It also can prevent excessive cell deformation or minimize the shear forces.

The separation efficiency of the cross-flow filtration is usually limited. This is because the particles/cells are mostly spread across the microchannels, with only the particles reaching the filtering region being sorted. To promote efficiency, Sethu et al. designed a diffusive channel to improve efficiency of cross-flow filtration. The chip design gradually expanded to both sides, generating larger pressure drop to pushed cells towered to filters. The device effectively sorted more than 90% of WBCs.27 Kuo et al. designed cross-flow filters with curve microchannels to continuously generate a centrifugal force, pushing the cells through the filters. This work showed separation efficiency of CTC (e.g., MCF-7, a human breast tumor-derived cell line) to 90%.28 Their approach mostly utilized novel channel designs to increase the pressure drop in the filters and to enhance the separation. They, however, have limited ability to deplete small particles. Li et al. designed a three-dimensional microchannel device with a porous PDMS membrane. A sheath flow was introduced to push the sample flow downward through the filters to improve the separation.16 The device incorporated complex fabrication, delicate bonding alignment, and difficult integration for downstream analysis.

In this work, a cross-flow filtration with an active approach is proposed to increase the pressure drop in the filters. It is a label-free method for separating particles of different sizes by introducing a buffer flow. The buffer flow provides two functions: it focuses particles on one side of the microchannels and lines particles to pass through the filter, while it causes a larger and controllable pressure drop in filters. Thus, it not only preserves the advantage of filtration mechanism in throughput and minimal clogging but also improves the separation efficiency in recovery rate and purity. The device is made by incorporating a standard soft lithograph technique with our newly developed pressurized bonding technique to create a high-aspect-ratio (HAR) filtration structures. All the inlet, outlet, filters, and channels are on the same plane to prevent alignment problem during fabrication—this permits possible integration with downstream analysis components.

MECHANISM

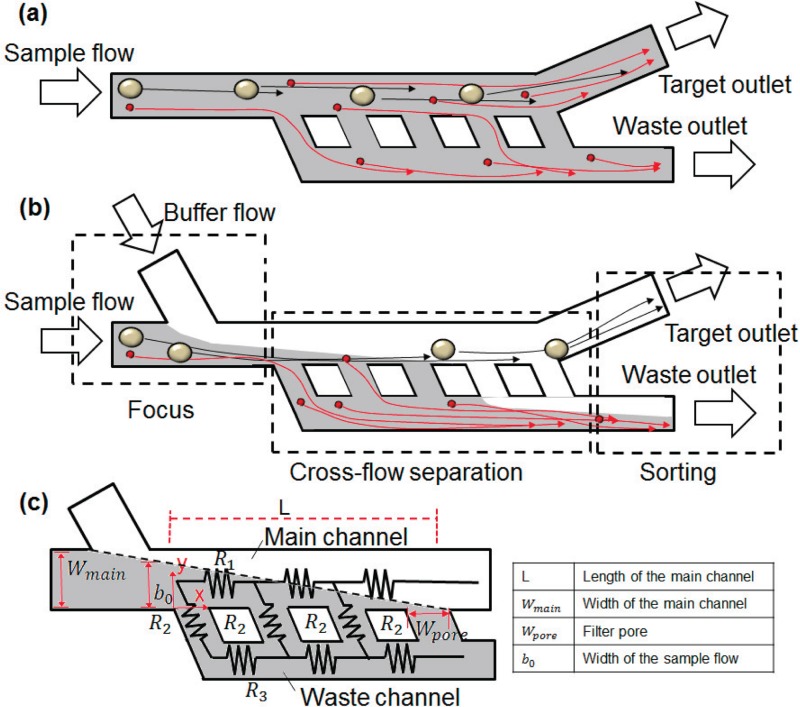

Cross-flow filtration typically has a configuration shown in Fig. 1(a). The particles from the sample flow spread across the microchannels with only the particles reaching the filters and passing through for filtration. This impedes separation efficiency. To promote separation efficiency, one straight forward approach is to push the particles to the filters for separation. Fig. 1(b) depicts the design of our cross-flow filtration. It consists of two inlets, two outlets, a main channel, a side channel, a waste channel, and microfilters. The main channel and waste channel are connected through an array of microfilters. A sample flow (the flow containing particles) is continuously introduced from the inlet into the channel, while a buffer flow (the flow with the same liquid but without particles) is injected into the main channel through a side channel from the buffer inlet. Once the flow with particle/cell samples is introduced, it is hydrodynamically focused by the buffer flow. The particles are concentrated and move closer to one side of the channels, and are then separated by the microfilters. Particles smaller than the filter size pass through the filter, move along the waste channel, and are collected from the outlet. Meanwhile particles larger than the filter size continuously move along the main channel and are collected from the target outlet.

FIG. 1.

Schematic of (a) typical cross-flow filtration and (b) our proposed separation mechanism. (a) The particles from the sample flow spread across the microchannels and only the particles reach to the filters passing through for filtration (b) The particles in the sample flow are concentrated by buffer flow and move toward one side of the channels, then are separated by the microfilters. Those particles, which are smaller than the filter size pass through the filter, move along the waste channel and are collected from the outlet. Meanwhile, other particles, larger than the filter size, continuously move along the main channel and are collected from the target outlet. (c) The flow channels are modeled to three different flow resistances R1 (for the main channel), R2 (for the filters), and R3 (for the waste channel). Key geometrical dimensions in our filtration mechanism: length of the main channel (L), width of the main channel (Wmain), width of the sample flow (b0), and width of filter pore (Wpore).

Introduction of the buffer flow from the side is very beneficial. It forms a boundary as a virtual wall for the sample flow for cross-flow filtration. Since the flow boundary is determined by the flow rate ratio of the sample flow to the buffer flow, it can be controlled and adjusted to the proper locations. The flow in the main channel can then be squeezed as wide as the size of the small particles to greatly enhance the efficiency of the cross-flow filtration.

Flow resistance

The sample flow in the typical cross-flow filtration can be modeled as a fluidic circuit with discrete resistive elements of R1 (for the main channel), R2 (for the filters), and R3 (for the waste channel), as shown in Fig. 1(c). Based on the Navier-Stokes equation for incompressible Newton's fluid, the flow resistance (R1) in a microchannel with a rectangular cross section can be obtained as

| (1) |

where L, Wmain, and H are the length, width, and height of the main channel. μ is the viscosity of the flow liquid, is the pressure difference between the inlet and the outlet, and Q is the volumetric flow through each element. The equation is applicable to R2 and R3, where the liquid flows between two fixed parallel plates when Wmain > H.

However, in our proposed cross-flow filtration, the flow resistance of the main channel (R1) is different due to the introduction of the buffer flow. The sample flow has a virtual boundary, which creates a slipping boundary condition. The width of the sample flow was defined as b0 after hydrodynamic focusing

| (2) |

where the width of the sample flow (b0) decreased as the sample flows passing through the filters.

The Navier–Stokes equation is then reduced to the velocity form, along with the slipping boundary problem where equal shear stress on the boundary between the sample and buffer flows. The fluidic resistance of R1 with the flow focusing effect is

| (3) |

where Wmain, L, and H are all fixed values. The width of the sample flow (b0) is controlled by the flow rate ratio between the sample and buffer flows. Based on Equation (3), as the width of the sample flow becomes smaller, the larger the flow resistance becomes in main channel. On the other hand, there is not a buffer flow in standard cross-flow filtration; its flow resistance solely depends on microchannel geometry. The width of the main channel (Wmain) is larger than the diameter of particles/cells. As a result, the particles/cells can smoothly flow through the channel. Sometime the channel width must be made much larger to prevent particles/cells from aggregation and blocking in the channel. Although wider channels provide higher loading capacity, it limits the efficiency for sample flow pass through the filter. In our cross-flow filtration, the width of the sample flow can be controlled by the flow rates of the sample and buffer flows. It can be small enough to create a high flow resistance in the main channel, thereby causing the sample flow to preferably pass through the region with a smaller flow resistance (e.g., R2, filters channel). Therefore, more sample flow can pass through the filter, creating a higher pressure drop and promoting filtration efficiency. The virtual boundary creates a very small width of the sample flow (b0), based on the mechanism of virtual boundary. It avoids particles blocked in the main channel providing a smooth flow in the main channel.

EXPERIMENTAL MATERIALS AND METHOD

Flow and pressure field simulation

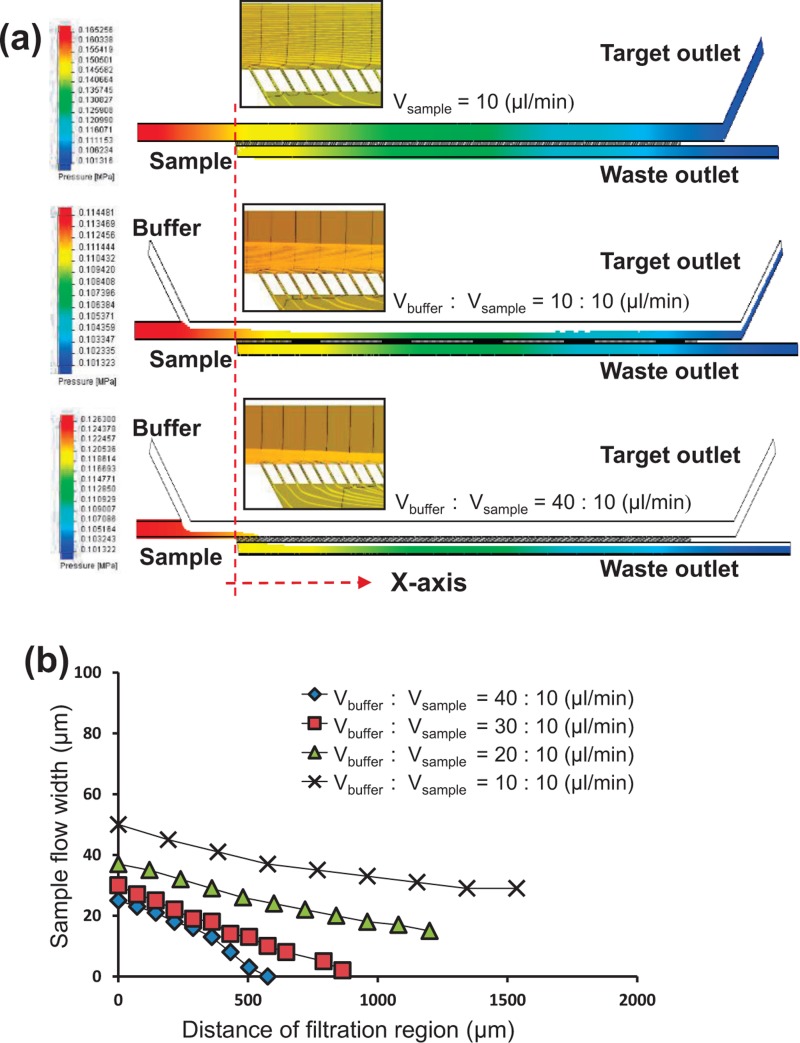

The flow fields in the microfluidic device were obtained from our simulation, as shown in Fig. 2(a). Without the buffer flow, most of the sample flow filled out the main channel and spread along the filter array. A portion of the flow and the particles would filter through and pass into the waste channel. When the buffer flow was introduced from the side channel, the majority of the flow was squeezed into the filters, so most of the particles were forced to be filtered. When the buffer was the same flow rate as the sample flow, 62% of the sample flow was filtered and passed into the waste channel. As the flow rate of the buffer flow increased to 40 μl/min, all the sample flow was filtered and passed into the waste channel. The color in Fig. 2(a) indicated the pressure field in the microchannel and the close-up image of the sample flow trajectories were under different flow rates between buffer and sample flow. The more sample flow trajectories passed through the filters, the greater part of the sample flow passed through the filters. When there was no buffer flow, the sample flow spread across the microchannel; with only a small portion of the sample flow reaching the filters for filtration. As the buffer flow increased to 40 μl/min, the sample flow trajectories were pushed toward the filter, with the width of the sample flow reduced from 100 μm to 25 μm. It greatly increased the flow resistance in the main channel and caused more of the sample flow to pass through the filters. The density of trajectories of the sample flow in the filter was then higher as the buffer flow rate increased.

FIG. 2.

(a) Trajectories of the sample flow from our three-dimensional flow simulation model. The color indicates the pressure gradient. The insets are the close-up views to locally display the trajectories of the sample flow around the filtration regions. The trajectories of the sample flow move toward the filtration regions while the buffer flows are at higher flow rates. The higher density of these flow trajectories indicates a greater portion of the sample flow being pushed through the filters with a larger pressure drop. (b) The relationship between the distance from the beginning of the filter region and the width of the sample flow.

Moreover, the buffer flow increased from 2.5 μl/min to 40 μl/min (the flow rate ratio changes from 0.25 to 4), leading to a larger pressure drop when the flow passed the filters. The x-axis direction was from the first filter to the outlet. The cross-flow filter with the buffer flow obviously increased the pressure drop in the filter and enhanced the efficiency.

In addition, when the buffer flow was introduced, the sample flow was gradually squeezed, moved toward the filter, and entirely passed through into the waste channel. The larger the flow rate ratio (of buffer-to-sample-flow), the smaller the width of the sample flow. As a result, the sample flow traveled shorter distance before completely passing through the filter, as shown in Fig. 2(b). In addition, the penetration length, defined as the distance where all the sample flow moved toward the filters and passing passed through into the waste channel, can be observed in Fig. 2(b). The penetration length was ∼850 μm when the buffer flow rate was 30 μl/min and ∼550 μm as the buffer flow rate was 40 μl/min. Our simulations confirmed that the buffer flow greatly changed the flow trajectory and increased the pressure drop in the filters, leading to enhancement in filtration efficiency.

Fabrication

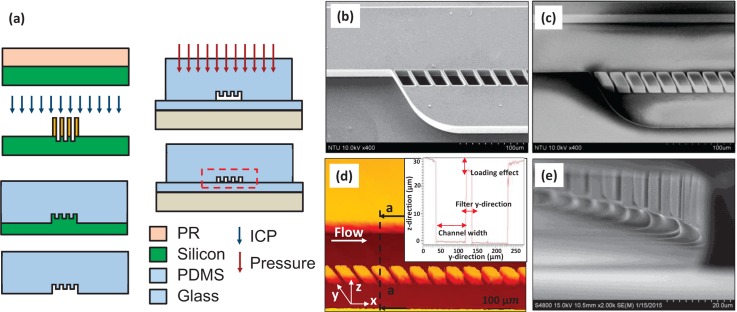

A soft lithography technique was used to fabricate the microchannel device with our cross-flow filtration mechanism. Positive photoresist was spun-coated on a (100) p-type 4 in. wafer to define the pattern. Deep reactive ion etching (DRIE) (SAMCO RIE-800 iPB, SAMCO, Inc., Fushimiku, Koyto, Japan) was used to etch away the silicon and to create the features, for obtaining the silicon mold. The silicon mold was silanized with (tridecafluoro-1,1,2,2-tetrahydrooctyl) trichlorosilane, before the mixture of polydimethylsiloxane or PDMS (Sylgard 184, Dow Corning, Midland, MI, USA) was applied onto silicon mold. After it was degassed, the PDMS mixture was cured, peeled, and cut. The PDMS was then punched to define the inlet and outlet of the microchannels. A new pressure-bonding technique, which was developed in our lab for making our filtration device, was utilized to bond the devices. Fig. 3(a) depicted the fabrication process.

FIG. 3.

(a) Fabrication process of our devices. (b) The silicon mold had a larger etching depth in the microchannel due to a large opening area and a shorter depth in the filter gap. (c) SEM picture for microchannel close to the inlet with microfilters. The picture shows the main channel, waste channel, and an array of filters with pores in rectangular cross section. The main channel is 100 μm wide, 30 μm high; the waste channel is 65 μm wide, 30 μm high; the filters has the quadrangle pore in 20 μm wide, 40μm long with a 60° tilt angle. There were 4 μm gaps between the filters. (d) The PDMS microchannel height was measured by an optic type surface analyser. (e) When the pressurized PDMS bonding technique was used at the pressure of ∼15 kPa, most of the filter areas were bonded onto the substrate.

One of the challenges in this fabrication process was to create a uniform structure height in the microchannels and to filter structures such that the hermetic bonding can be ensured for filtration. In particular, the microloading effect during the DRIE process led to different etching depths on silicon depending on the areas exposed to the etchant.29 The silicon mold in Fig. 3(b) had a larger etching depth in the microchannel due to larger opening areas and a shorter depth in the filter gap with the PDMS having severe variations in the structure height. The surface profile of the PDMS microchannel (Fig. 3(c)) was measured by using an ellipso-interferometer and shown in Fig. 3(d).

The pressurized PDMS bonding technique was developed to overcome the hurdle associated with the microloading effect. This bonding technique was necessary to ensure hermetic bonded PDMS structures such that only small particles passed through the filters, rather than through the gaps caused by the microloading effect. First, a thin layer of PDMS was applied and spun onto glass then cured. Another layer of PDMS was applied and spun again, but partially cured. The PDMS surface was then treated by oxygen plasma before the final PDMS layer of the device structures was placed for bonding. During the bonding step, a digital force gauge (HF-5, ALGOL Instrument Co., Ltd., Taoyuan, Taiwan) and an X-Y stage were utilized. Without application of a pressurized bonding technique, a 5 μm space was found without any areas bonded. As a larger bonding pressure was applied, more areas were bonded. Fig. 3(e) showed that the filter areas mostly bonded onto the substrates. In addition, the filter dimension was also found similar to our designed values, as the PDMS layer of the device structures was fully cured before the pressurized bonding.

Numerical simulations

To realize our separation mechanism, finite element analysis was conducted. The simulation was performed by applying different combinations of the flow rates in the sample and buffer flows to verify the flow focusing effect. Finite element modeling was carried out using the commercial software, SolidWorks 2012 flow simulation (SolidWorks Corp., Waltham, MA, USA). The flow field was governed by the Navier–Stokes equations for incompressible fluid. A three-dimensional model was used in our simulation.

Noteworthy is that the presence of the particles introduced additional hindrance and modified the local stress field of the carrier fluid, as done by the pressure gradient. Close to the actual situation, the buffer flow was modeled as phosphate buffered saline (PBS) with a density (ρ) of 1 kg/m3 and a dynamic viscosity (μ) of 1.05 mPa s. The sample flow was suspension in particles. The relative viscosity (μr) of the sample flow—mixtures of solid particles and liquid (PBS)—can be described as relative to the viscosity of the liquid phase. Depending on the size and concentration of the solid particles, the relative viscosity was a function of volume fraction () of the solid particles. It was reasonably approximated by Einstein's equation, in the case of extremely low particle concentrations ( < 0.05)30–32

| (4) |

In our simulation, the particles were assumed to move along the sample flow with two liquid phases (e.g., the sample and buffer flows) included. The flow rate of the sample flow (Vsample) was 10 l/min, while the flow rate of the buffer flow (Vbuffer) increased from 2.5 μl/min to 40 l/min. The outlet was set to a fixed environmental pressure boundary condition. The mesh volume was 10−7 mm3.

SAMPLE PREPARATION

Particle preparation

Polystyrene particles of 2.7 μm (FP-3056–2, Spherotech, Inc., Lake Forest, IL, USA) and 10.6 μm (SVP-100–4, Spherotech, Inc., Lake Forest, IL, USA) in diameters were mixed with an equal concentration of 1 104 particles/ to emulate cells at different sizes in common separation process. The device was mounted onto the stage of a microscope (Axio Observer.A1, Carl Zeiss Micro Imaging GmbH, Göttingen, Germany) with a CCD camera and a video monitoring system (ORCA-Flash4.0, Hamamatsu, Japan). The particle mixtures in the sample flow were introduced into the device using a syringe, controlled by a syringe pump.

The syringe was filled with PBS buffer before the sample flow was extracted. An air bubble was usually introduced in between the initial PBS buffer and the sample flow to prevent the sample sediment. PTFE tubing (LeoFlon Electronics, Taipei, Taiwan) was used for fluidic connection. Once the particles were flown into the chip and separated, the particles were collected from target and waste outlets for evaluation. Flow cytometer was used to quantify the populations of the particles in both outlets.

Recovery rate and purity are two common parameters for evaluating separation efficiency. The recovery rate was defined as the ratio of the number of the particles retrieved from the target outlet to the number of the particles introduced into the inlet. The purity was defined as the ratio of the number of the target particles from the outlet to the number of the total particles from the outlet

| (5) |

| (6) |

where was the number of the target particles (e.g., particles of the interests) and was the number of the waste particles.

Cell preparation

Human prostate cancer cell lines (PC3 cells) were employed to exemplify the ability of our device in cell separation. Before spiked PC3 cells into whole blood, PC3 cells were dyed with CellTrackTM Red (Life Technology, Inc., Grand Island, NY, USA) to discern PC3 cells from the other cells. After PC3 cells were dyed with CellTrackTM Red, the PC3 cells were spiked into whole blood then dyed with nuclear DNA (e.g., PC3 cells and WBCs) with Hoechst 33342 (Life Technology, Inc., Grand Island, NY) to discern PC3 cells and WBCs from RBCs. The stock solution was diluted to the concentration of 10 mg/ml in serum free medium. PC3 cells was 16–20 μm in diameter, WBCs was 10–15 μm in diameter, and RBCs was 6–8 μm in diameter with 2–3 μm in thickness.

RESULT AND DISCUSSION

Particle passing through filter

Once our device was made, its flow pattern was examined. An array of the microfilters with the rectangular pores in 4 μm wide and 30 μm high was employed. To observe the virtual boundary between the sample and buffer flows, blue ink (Refill ink RF-PM32, Lion Pencil Co., Taipei, Taiwan) was injected as the buffer flow, while deionized (DI) water was injected as the sample flow, respectively, at an equal constant flow rate of 1 μl/min (Fig. 4(a)). The width of the sample flow was approximately 50 μm when two flows initially merged (Fig. 4(a-i)). The sample flow width decreased in the microchannel (Fig. 4(a-ii)), and most of the sample flow was focused to the waste outlet (Fig. 4(a-iii)).

FIG. 4.

(a) A virtual flow boundary was formed between the sample flow (e.g., DI water) and buffer flow (e.g., blue ink). Both flows were pushed into the microchannel at an equal flow rate of 1/min. (a-i) The width of the sample flow (b0) was 50 μm when two flows initially merged. (a-ii) The sample flow width gradually decreased as the flow proceeded in the microchannel. (a-iii) Most of the sample flow was pushed through the filter into the waste outlet. (b) The images of the particles moving along in the microchannel showed the filtration process in three steps: (b-i) the particles in the sample flow were pushed toward one side of the channel (particle-focusing step); (b-ii) small particles passed through the filters and flowed into the waste channel while large particles remained in the main channel (particle filtration step); and (b-iii) most of the small particles were in the waste channel and proceeded, while the large particles in the main channel, even though the sample flow had mostly flown into the waste channel (particle isolation step).

Further examinations were conducted to reveal the moving trajectories of the particles, as shown in Fig. 4(b) The mixtures of the particles of diameter of 2.7 μm and 10.6 μm with PBS were injected into the sample inlet, while the buffer flow of PBS was injected into the buffer inlet; both of the flow rates were equally set at 1 μl/min. In the beginning, the particles in the sample flow were focused to one side of the microchannel by the buffer flow (Fig. 4(b-i)). The small particles passed through the filter, while the large particles remained in the main channel (Fig. 4(b-ii)). As they proceeded to move along, most of the small particles were in the waste channel, while the large particles in the main channel, even though the sample flow mostly deposited into the waste channel (Fig. 4(b-iii)). The experiment results confirmed the particle trajectory as our proposed mechanism (shown in Fig. 1(b)).

The experiment demonstrated that the buffer flow creates a moving virtual boundary for pushing the sample flow and narrowing the sample flow width. As it proceeded, it was possible for the sample flow to have a width smaller than the particles, making all the particles reach the filters for separation. Compared to the fixed flow boundary in the traditional cross-flow filtration, our proposed mechanism utilized the moving virtual boundary to actively push all the particles for separation. In addition, by gradually filtering the sample flow by filters to achieve smaller width of sample flow, this mechanism allowed higher flow rates of the sample/buffer flows than the pinched flow filtrations did.9,11

Separation of particles

To evaluate the separation performance of our filtration device, the microparticles with diameters of 2.7 μm and 10.6 μm were tested. The particles were thoroughly mixed an equal concentration of 1 × 104 μl−1 before flowing into the chip at a constant flow rate for filtration. Afterwards, the microparticles were collected from the target and waste outlets, then counted using the flow cytometer (BD FACSAria™ III, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

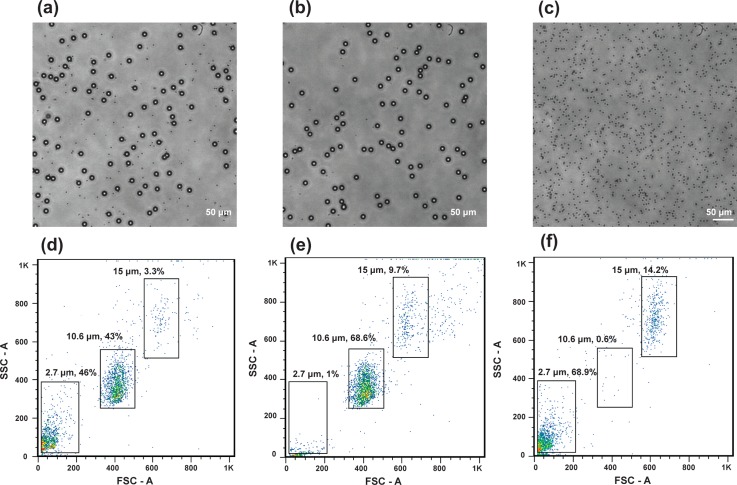

Figs. 5(a)–5(c) showed the microscope images of the solution with the particles before the filtration, as well as the particle images recovered from the target outlet and waste outlet. The filtration was conducted at the flow rates of 40:10 (μl/min) for Vbuffer:Vsample. A mixture of the particles at two different sizes was observed (Fig. 5(a)), while 10.6 μm particles were mostly found in the target outlet (Fig. 5(b)) and 2.7 μm particles were mostly found in the waste outlet (Fig. 5(c)), both with high purity.

FIG. 5.

(a)–(c) Representative microscopic images showed: (a) the mixture of the microparticles of 2.7 μm and 10.6 μm before separation, (b) the samples collected from the target outlet after separation, and (c) the samples collected from the waste outlet after separation. (d)–(f) Flow cytometer data indicated: (d) Relative concentration of the samples before separation, (e) relative concentration of the samples collected from the target outlet, and (f) relative concentration of the samples collected from the waste outlet. Note: The numbers near the gated groups represented the percentage of the grouped particle amount to the total particle amount.

Figs. 5(d)–5(f) further showed the measurement results from the flow cytometer data (plotted as forward scatter FSC and side scatter SSC). The data were subdivided by gating upon specific populations for three types of the particles (i.e., diameters = 2.7 μm, 10.6 μm, and 15 μm). The 15 μm particles (ACBP-150–10, Spherotech, Inc., Lake Forest, IL, USA) were used as the reference particles with known concentration for particle counting. The number near the gated group represented the percentage of the group number on the total particle events. There were 42% concentration for 2.7 μm particles and 43% concentration for 10.6 μm particles from sample inlet. The 3.3% concentration for 15 μm particles were used to quantify the total number of the 2.7 μm and 10.6 μm particles. As shown in Figs. 5(e) and 5(f), the 2.7 μm particles were mostly depleted in the target outlet and collected in the waste outlet. Our target particles were mostly collected in the target outlet.

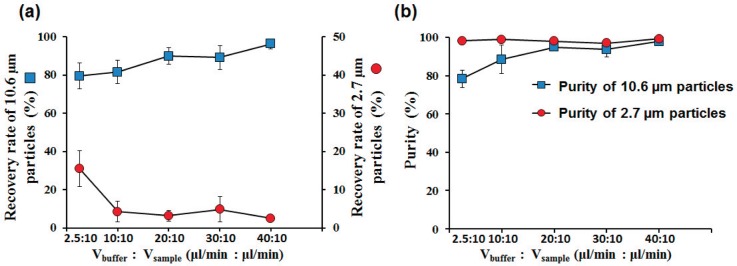

Different flow rates were tested and evaluated for the separation efficiency. The particle purity and recovery rate were measured and shown in Fig. 6. When the flow rates were 2.5:10 (μl/min) for Vbuffer:Vsample, the recovery rate for 10.6 μm particles was 79.4 6.8%, and the recovery rate for 2.7 μm particles was 15.5 4.6%. Most small particles were pushed to the filters, freely passing through the filters and sorted out from the waste outlet. While in this buffer flow condition, the width of sample flow was not small enough to push all of the small particles passed through the filters. Some of small particles flowed in the main channel and sorted out from the target outlet, with just a few small particles being aggregated and clogged in the filters. The diameter of the large particles was larger than the width of filter pores, preventing large particles from passing through the filters. These large particles mostly flowed along the main channel and sorted out from the target outlet. Only a few large particles were found on the filters in the main channel, causing a portion of large particles to be lost in the microchannel. There was no large particles found in waste outlet.

FIG. 6.

Separation efficiency of our devices at different flow conditions: (a) Recovery rates of the large particles (in the target outlet) and small particles (in the waste outlet) as the buffer flow rate increased from 2.5 μl/min to 40 μl/min (Vsample = 10 μl/min). (b) The purity of the large particles and small particles as the buffer flow rate increased from 2.5 μl/min to 40 μl/min.

The recovery rate of the large particles in the target outlet increased from 79.4 6.8% to 96.2 2.8% when the flow rates changed from 2.5:10 (μl/min) to 40:10 for Vbuffer:Vsample. Most of the 10.6 μm particles were found in the target outlet. On the other hand, the recovery rate of the 2.7 μm particle decreased from 15.6 4.7% to 2.5 0.4% when the flow ratio changed from Vbuffer:Vsample = 2.5:10 (μl/min) to 40:10. Only few of 2.7 μm particles were found in the target outlet while most of them were in the waste outlet (Fig. 6(a)).

The purity of large particle in the target outlet increased from 78.4 4.5% to 97.9 0.5% when the flow rates changed from 2.5:10 (μl/min) to 40:10 for Vbuffer:Vsample. It is one of the best separation efficiencies among current techniques. The purity of small particles in the waste outlet was higher than 97% in all flow conditions (Fig. 6(b)).

Separation of PC3 cells spiked in blood samples

To test our device on the separation of biological cells, known quantities of cancer cell line, PC3 cells, were spiked into whole blood. The cells were first counted and discerned by using the flow cytometer. Afterwards, the device performance was evaluated in two aspects: (i) the recovery rates at different flow rate ratios and (ii) the recovery rates at different PC3 cell concentrations. The total sample volume used in each experiment was 50 μl.

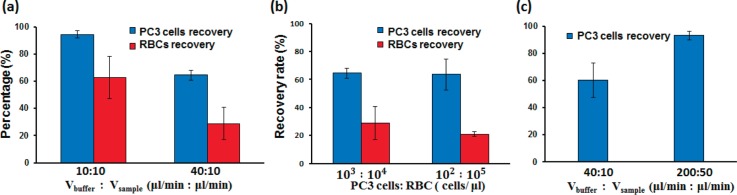

In the first part, two flow rate ratios were tested for the separation efficiency as the concentration of PC3 cells:RBCs was 103:104 cells/μl. As shown in Fig. 7(a), when the flow rates changed from 10:10 (μl/min) to 40:10 for Vbuffer:Vsample, the recovery rate of PC3 cells was reduced from 94.5 2.5% to 64.4 3.5%, while the recovery rate of RBCs was reduced from 62.5 15.5% to 28.8 11.8%.

FIG. 7.

(a) PC3 cells were spiked in to whole blood at the concentration of PC3:RBCs = 103:104 cells/μl for testing. The recovery rates of PC3 cells and RBCs at the concentrations of 103:104 cells/μl for PC3 cells:RBCs, as the flow rates changed from Vbuffer:Vsample = 10:10 (μl/min) to 40:10. (b) PC3 cells were spiked in to whole blood at the two different concentrations (PC3:RBCs = 102:105 and 103:104 cells/μl) for testing. The recovery rates of PC3 cells and RBCs at the flow rates of 40:10 (μl/min). (c) The recovery rates of PC3 cells as the flow rates changed from 40:10 (μl/min) to 200:50.

In the second part, a lower concentration of PC3 cells was tested to emulate to the practical situation, where PC3 cells were rare cells in blood. PC3 cells were spiked into whole blood at the concentration (PC3 cells:RBCs) of 102:105 cells/l with flow rates of 40:10 (μl/min). The recovery rate of PC3 cells and RBCs were 63.5 11% and 20.9 1.7%, as shown in Fig. 7(b).

The separation efficiency for the cells differed from the one for the particles as the biological cells were soft and deformable.28 In our experiment, RBCs were smaller than PC3 cells, and biconcave disk in shape with a flattened center and no nucleus. Compared with PC3 cells, they were easier to pass through the filters. Most of the RBCs were sorted out and found in the waste outlet. On the other hand, PC3 cells were larger and with nucleus, so they were less likely to pass through the filters. Most of the PC3 cells were found in the target outlet, with few PC3 cells found in the waste outlet. Moreover, these PC3 cells tended to clog, as the flow rate of the buffer flow increased with a higher pressure drop obtained to push and deform larger cells into the filters.

It was postulated that elevated flow rate made the RBCs easier to pass through the filters and clogged the PC3 cells in the filters, so the recovery rate suffered. To further improve the recovery rate of PC3 cells, the sample with only PC3 cells in the whole blood (no RBCs) was employed. The flow ratios were fixed at Vbuffer:Vsample = 4:1 during the experiments. The recovery rate of the PC3 cells increased from 60.3 12.7% to 93.1 3.3% as the flow rates changed from 40:10 (μl/min) to 200:50 for Vbuffer:Vsample. The recovery rate of the PC3 cells was effectively promoted by increasing the overall flow rate (Fig. 7(c)).

Isolating PC3 cells (as the model cells for rare cells or CTCs) has been technically challenging because from a practical perspective; these cells are in extremely low concentrations (1 in 109 blood cells) and have low recovery following traditional purification procedures. Although the samples used in our tests have higher concentrations than the ones that practically occur for easy observation during experiments, the samples with lower concentrations can also be applied in our device. The separation efficiency is expected to be higher, as the high recovery rates from our devices represent our target cells (e.g., PC3 cells) and mostly remain in the main channels. The high recovery rate represents the device capability to confidentially isolate PC3 cells with very few loss in target cells for downstream analysis, which is practically critical in rare cell applications.

Finally, our device has shown relatively high recovery rates at the flow rate up to 200 μl/min with comparable throughputs to most of the existing works.16,26–28 Although higher separation efficiency at larger flow rates can be achieved, our results presented in this article preserves the flow rate conditions to ensure reasonable shear stress and less cell deformation during the cell separation procedures.

CONCLUSION

The study presented a novel cross-flow filtration technique by introducing a hydrodynamic focusing strategy to improve the separation efficiency. A pressurized PDMS bonding technique was developed to overcome the microloading effects and to make devices with a high-aspect-ratio filtration structures. This was a necessity to ensure small particles only passed through the filters. The filtration structures provided a more robust structure for higher flow rates. The highest throughput reached 50 μl/min for sample flow and 200 μl/min for buffer flow. The testing results showed our proposed mechanism to have great potential as a cost-effective, process-integrable method with a high recovery rate and high purity to support particle and cell separation applications.

A mixture of the particles at different sizes was successfully separated. 96.2 2.8% of 10.6 μm particles were recovered with 97.9 0.5% purity while 97.5 0.4% of 2.7 μm particles were depleted with 99.2 0.4% purity—one of the best separation efficiencies among current techniques. Further, the experiment demonstrated the microchip's ability in cells' separation. A mixture of PC3 cells and whole bloods was successfully separated. 94.5 2.5% of PC3 cells were recovered while 37.5 15.5% of RBCs were depleted at the flow rates of 10:10 (μl/min) for Vbuffer:Vsample. 64.4 3.5% of PC3 cells were recovered, while 71.2 11.8% of RBCs were depleted at the flow rate of 40:10 (μl/min). All the above results showed our proposed mechanism to have great potential as a cost-effective, process-integrable method with a high recovery rate and high purity to support particle and cell separation applications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. J.-W. Hsu from the Department of Animal Science at National Taiwan University (NTU) for the discussion in particle and cell separations; Dr. F. Yang from the Department of Mechanical Engineering at NTU for the discussion in suspension flow; as well as Dr. L.-C. Chen and Dr. Y.-T. Hou for providing the PC3 cell lines. The authors acknowledge Nano-Electro-Mechanical-System (NEMS) Research Center at NTU for the technical support in microfabrication, as well as Technology Commons, College of Life Science and Instrumentation Center at NTU for the assistance in flow cytometer and SEM. The authors also thank Ms. T. Kirk for manuscript editing. This project has been supported by Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST 102-2221-E-002-084-MY3 and 103-2321-B-002-076).

References

- 1. Sajeesh P. and Sen A. K., “ Particle separation and sorting in microfluidic devices: A review,” Microfluid. Nanofluid. 17(1), 1–52 (2013). 10.1007/s10404-013-1291-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yu Z. T., Aw Yong K. M., and Fu J., “ Microfluidic blood cell sorting: Now and beyond,” Small 10(9), 1687–1703 (2014). 10.1002/smll.201302907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tripathi S. et al. , “ Passive blood plasma separation at the microscale: A review of design principles and microdevices,” J. Micromech. Microeng. 25(8), 083001 (2015). 10.1088/0960-1317/25/8/083001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wu Z. et al. , “ Soft inertial microfluidics for high throughput separation of bacteria from human blood cells,” Lab Chip 9(9), 1193–1199 (2009). 10.1039/b817611f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Azim W. et al. , “ Diagnostic significance of serum protein electrophoresis,” Biomedica 20(1), 40–44 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hou H. W. et al. , “ Microfluidic devices for blood fractionation,” Micromachines 2(4), 319–343 (2011). 10.3390/mi2030319 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moreno J. G. et al. , “ Circulating tumor cells predict survival in patients with metastatic prostate cancer,” Urology 65(4), 713–718 (2005). 10.1016/j.urology.2004.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lin C.-H. et al. , “ Novel continuous particle sorting in microfluidic chip utilizing cascaded squeeze effect,” Microfluid. Nanofluid. 7(4), 499–508 (2009). 10.1007/s10404-009-0403-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Takagi J. et al. , “ Continuous particle separation in a microchannel having asymmetrically arranged multiple branches,” Lab Chip 5(7), 778–784 (2005). 10.1039/b501885d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yamada M. and Seki M., “ Hydrodynamic filtration for on-chip particle concentration and classification utilizing microfluidics,” Lab Chip 5(11), 1233–1239 (2005). 10.1039/b509386d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Morijiri T. et al. , “ Sedimentation pinched-flow fractionation for size- and density-based particle sorting in microchannels,” Microfluid. Nanofluid. 11(1), 105–110 (2011). 10.1007/s10404-011-0785-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lin B. K. et al. , “ Highly selective biomechanical separation of cancer cells from leukocytes using microfluidic ratchets and hydrodynamic concentrator,” Biomicrofluidics 7(3), 034114 (2013) 10.1063/1.4812688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Alvankarian J., Bahadorimehr A., and Majlis B. Y., “ A pillar-based microfilter for isolation of white blood cells on elastomeric substrate,” Biomicrofluidics 7(1), 14102 (2013). 10.1063/1.4774068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen X. et al. , “ Microfluidic chip for blood cell separation and collection based on crossflow filtration,” Sens. Actuators, B 130(1), 216–221 (2008). 10.1016/j.snb.2007.07.126 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sollier E. et al. , “ Passive microfluidic devices for plasma extraction from whole human blood,” Sens. Actuators, B 141(2), 617–624 (2009). 10.1016/j.snb.2009.05.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li X. et al. , “ Continuous-flow microfluidic blood cell sorting for unprocessed whole blood using surface-micromachined microfiltration membranes,” Lab Chip 14(14), 2565–2575 (2014). 10.1039/c4lc00350k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mohamed H., Turner J. N., and Caggana M., “ Biochip for separating fetal cells from maternal circulation,” J. Chromatogr. A 1162(2), 187–192 (2007). 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen C. L. et al. , “ Separation and detection of rare cells in a microfluidic disk via negative selection,” Lab Chip 11(3), 474–483 (2011). 10.1039/C0LC00332H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hur S. C., Mach A. J., and Di Carlo D., “ High-throughput size-based rare cell enrichment using microscale vortices,” Biomicrofluidics 5(2), 022206 (2011). 10.1063/1.3576780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhou J., Kasper S., and Papautsky I., “ Enhanced size-dependent trapping of particles using microvortices,” Microfluid. Nanofluid. 15(5), 611–623 (2013). 10.1007/s10404-013-1176-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Choi S. and Park J. K., “ Continuous hydrophoretic separation and sizing of microparticles using slanted obstacles in a microchannel,” Lab Chip 7(7), 890–897 (2007). 10.1039/b701227f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kim T. H. et al. , “ Cascaded spiral microfluidic device for deterministic and high purity continuous separation of circulating tumor cells,” Biomicrofluidics 8(6), 064117 (2014) 10.1063/1.4903501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Burke J. M. et al. , “ High-throughput particle separation and concentration using spiral inertial filtration,” Biomicrofluidics 8(2), 024105 (2014). 10.1063/1.4870399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ramachandraiah H. et al. , “ Dean flow-coupled inertial focusing in curved channels,” Biomicrofluidics 8(3), 034117 (2014). 10.1063/1.4884306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Di Carlo D. et al. , “ Continuous inertial focusing, ordering, and separation of particles in microchannels,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104(48), 18892–18897 (2007). 10.1073/pnas.0704958104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ji H. M. et al. , “ Silicon-based microfilters for whole blood cell separation,” Biomed. Microdevices 10(2), 251–257 (2008). 10.1007/s10544-007-9131-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sethu P., Sin A., and Toner M., “ Microfluidic diffusive filter for apheresis (leukapheresis),” Lab Chip 6(1), 83–89 (2006). 10.1039/B512049G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kuo J. S. et al. , “ Deformability considerations in filtration of biological cells,” Lab Chip 10(7), 837–842 (2010). 10.1039/b922301k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kuehl K. et al. , “ Advanced silicon trench etching in MEMS applications,” Proc. SPIE 3511, 97 (1998). 10.1117/12.324331 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Einstein A., Eine neue Bestimmung der Moleküldimensionen, 1905.

- 31. Simha R. “ The influence of Brownian movement on the viscosity of solutions,” J. Phys. Chem. 44(1), 25–34 (1940) 10.1021/j150397a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Roscoe R., “ The viscosity of suspensions of rigid spheres,” Br. J. Appl. Phys. 3(8), 267 (1952) 10.1088/0508-3443/3/8/306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]